Abstract

Knowing provoking factors of vitiligo progression and how to avoid them is essential to the successful self-management of vitiligo. Cultivating a positive attitude is also essential to avoid focusing on the negative aspects of the disease and to fuel proactive practice. This study aims to evaluate the knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) of vitiligo patients and identify related factors. The study recruited 517 (54.55% male) adult vitiligo patients in Beijing and Nanjing. The mean knowledge, attitude, and practice scores were 5.45 ± 2.74 (possible range: 0–10), 23.15 ± 6.78 (possible range: 8–40), and 37.13 ± 6.78 (possible range: 10–50), respectively. Mediation analysis indicated that knowledge (β = 0.24, P = 0.023), attitude (β=-0.28, P < 0.001), disease duration (β=-1.49, P < 0.001), and negative emotions (β=-1.54, P = 0.008) had direct effects on practice. Income (β=-0.29, P = 0.003), disease duration (β = 0.16, P = 0.033), lesion duration (β = 0.25, P = 0.003), education (β = 0.11, P = 0.024), and age (β=-0.14, P = 0.036) had indirect effects on practice. Vitiligo patients exhibited significant gaps in knowledge and attitudes toward their condition despite active management practices. Given the chronic nature of vitiligo and its slow treatment response, tailored health education strategies focusing on improving knowledge and attitudes are essential for standardizing treatment and enhancing patient adherence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vitiligo is an autoimmune skin disorder characterized by an absence of pigmentation due to the loss of functioning melanocytes1. The prevalence of vitiligo is reported at 0.09–1.9% in different regions of China2. The provoking factors include stress, sunburn, and mechanical and chemical reactions3. The management is based on cosmetic camouflage, topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, topical vitamin D analogs, topical Janus kinase inhibitors, phototherapy, and excimer laser therapy4,5,6,7. Vitiligo can increase the risk of sunburn and implies possible psychological complications related to self-appearance1, but the disease will not affect the lifespan of the patients.

Stressful life events may be associated with the onset of vitiligo8,9,10. For patients, avoiding potential provoking factors, such as stress, sunburn, and mechanical and chemical irritation, is recommended11. Therefore, self-management appears to be at the core of preventing vitiligo progression by avoiding provoking factors. Still, knowing the triggers and how to avoid them is essential to the successful management of vitiligo. Cultivating a positive attitude is also essential to avoid focusing on the negative aspects of the disease and to fuel proactive practice. Indeed, the patients should know about their disease. Even if many lesion progression events cannot be linked to a precise provoking factor, avoiding the suspected provoking factors could do no harm. In addition, better knowledge could be associated with better disease management.

Knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) studies provide quantitative and qualitative data about knowledge gaps and misconceptions that can represent barriers to the correct performance of subjects in specified populations12,13. Previous studies in general populations showed that the KAP toward vitiligo was relatively poor to moderate14,15,16,17,18. Still, the participants in those previous studies14,15,16,17,18 probably had a higher likelihood of poor KAP because they were not necessarily affected by vitiligo. However, there were no previous study specifically investigated the KAP toward vitiligo among vitiligo patients, especially in Chinese patients. Because they are the ones suffering from the condition, knowing where the KAP of patients with vitiligo stands is essential to designing and implementing educational interventions to improve the self-management of vitiligo.

A mediation analysis is a type of structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis, which can be used as a surrogate of causality analysis to test hypotheses based on the literature19,20,21. The KAP conceptual framework indicates that knowledge is the basis for practice, while attitude is the force driving practice12,13. Hence, it was hypothesized that (1) knowledge directly influences attitudes, (2) knowledge directly influences practice, (3) attitudes directly influence practice, (4) knowledge indirectly influences practice through attitudes, and (5) demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical factors affect the three KAP dimensions.

Therefore, this study aimed to examine the KAP toward vitiligo among patients with this disease and explore the factors associated with KAP.

Methods

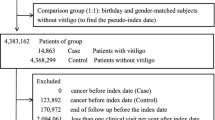

Study design and participants

This web-based cross-sectional study enrolled patients with vitiligo at Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, and Dermatology Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Institute of Dermatology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences) between October 2022 and June 2023. The inclusion criteria were: 1) diagnosed with vitiligo, irrespective of treatments and disease status; 2) ≥ 18 years old; and 3) voluntarily participating. Patients with vitiligo who were unwilling to participate were excluded. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, and the Medical Ethics Committee of Dermatology Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (approval # KY2022-188-02 and 2022-KY-070, respectively). All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. All participants provided informed consent before completing the survey. The informed consent statement was on the first page of the questionnaire, just below the study presentation and explanation. Ticking the box “I consent to participate in this study” was mandatory to gain access to the questionnaire.

Questionnaire introduction

The self-administered questionnaire was developed with reference to the Consensus on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Vitiligo (2021 version)22and Guidelines for the Management of Vitiligo (2013 version)11. In the first revision, three dermatologists provided comments; the questions on reimbursement and vitiligo types and stage (demographic characteristics section) were revised, and a question on “Chinese medicine treatment” was added (practice section). In the second revision, two dermatovenereologists made comments; additional questions were added on substance exposure at work and previous medical conditions (basic information) and knowledge about new developments in treatments (practice section). A pre-test showed a Cronbach’s α of 0.784, indicating good internal consistency.

The final questionnaire contained four dimensions: demographic characteristics, knowledge dimension, attitude dimension, and practice dimension. The knowledge dimension consisted of 10 questions, with 1 point for correct answers and 0 points for wrong or unclear answers, ranging from 0 to 10 points. The attitude dimension consisted of eight questions, using a 5-point Likert scale, with two positive attitude questions with a score of 5 points to 1 point for strongly agree to strongly disagree and six negative attitude questions with a score of 1 point to 5 points for strongly agree to strongly disagree, ranging from 8 to 40 points. The practice dimension contained 10 questions, using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from always (5 points) to never (1 point), with scores ranging from 10 to 50. Adequate knowledge, positive attitude, and proactive practice were defined by a score of ≥ 70% for each dimension23.

Questionnaire distribution & quality control

The questionnaires were administered to patients visiting the hospital through convenience sampling. The electronic questionnaire was created using an online platform (Sojump), and a QR code was generated for the electronic questionnaire. The participants scanned the QR code sent via WeChat or clicked on the link to log in and fill out the questionnaire. In order to ensure the quality and completeness of the questionnaire, each IP address could only be used once to submit a questionnaire, and all items were mandatory. The research team members checked all questionnaires for completeness, internal consistency, and reasonableness (e.g., impossible age, illness duration, or treatment duration). Eight doctors and nurses responsible for promoting and distributing the questionnaires were trained for this study and acted as research assistants. The questionnaires with logical errors or where the options selected were identical were considered invalid.

Statistical analysis

Stata 17.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) was used for analysis. The continuous variables were found to have a normal distribution according to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; they were expressed as mean ± standard deviations (SD) and were analyzed using the t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The categorical data were expressed as n (%). Pearson correlation analysis was used to evaluate the correlation between the knowledge, attitude, and practice scores. A mediation analysis was used to validate the hypotheses stated in the Introduction. The variables that were significantly associated with each KAP dimension in the univariable analyses were included in the mediation model. Based on these results, we conducted an initial mediation analysis, then excluded the non-significant variables. The final mediation model was fitted using only the significant variables. The goodness-of-fit of the model was tested using the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and the comparative fit index (CFI). The threshold criteria for goodness-of-fit of the mediation analysis were RMSEA < 0.08, SRMR < 0.08, TLI > 0.8, and CFI > 0.824,25,26. Two-sided P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics

A total of 521 questionnaires were collected, but four showed logical errors and were excluded, resulting in 517 valid questionnaires. The majority were males (54.55%), the participants aged ≤ 30 years represented 40.62%. Among the participants, 296 (57.23%) were living in an urban setting (57.25%), 297 (57.45%) held junior college/undergraduate education or above, 308 (59.57%) were married, 234 (45.26%) had a monthly income < 5000 CNY, 272 (52.61%) were working indoors only, 478 (91.88%) had no environmental/occupational exposure, 106 (20.50%) had a history of sunlight exposure < 3 months prior to vitiligo onset, 229 (44.29%) had vitiligo for ≤ 1 year, 250 (48.36%) had been treated for < 3 months, 68 (13.15%) had a family history of vitiligo, and 246 (47.58%) had a history of stress, anxiety, overwork, impatience, or psychological trauma (Table 1).

The knowledge, attitude, and practice scores were 5.45 ± 2.74 (possible range: 0–10), 23.15 ± 6.78 (possible range: 8–40), and 37.13 ± 6.78 (possible range: 10–50), respectively. Differences in knowledge scores were observed with age groups (P < 0.001), residence (P < 0.001), education (P < 0.001), marital status (P < 0.001), type of work (P < 0.001), medical insurance (P = 0.024), disease duration (P = 0.001), disease stage (P < 0.001), duration of vitiligo treatment (P < 0.001), family history (P = 0.002), and presence of negative emotions (P = 0.013). Differences in attitude scores were observed with education (P = 0.024), income (P < 0.001), type of work (P = 0.001), disease duration (P = 0.001), lesion location (P < 0.001), and disease stage (P < 0.001). Differences in practice scores were observed with type of work (P = 0.028), medical insurance (P = 0.032), disease duration (P = 0.028), and negative emotions (P = 0.039) (Table 1).

Knowledge, attitude, and practice dimensions

The two knowledge items with the lowest correctness rates were K1 (3.09%; “Vitiligo is an infectious disease.”) and K8 (3.48%; “Once vitiligo has been cured, it will not recur.”). The two knowledge items with the highest correctness rates were K9 (71.57%; “Patients treated for vitiligo should avoid exposure to sunlight.”) and K10 (71.18%; “Psychological trauma or excessive stress in life can also trigger vitiligo.”). Among the participants, 91.10% at least agreed that it is necessary to learn about vitiligo (A1), 80.86% at least agreed that vitiligo made them anxious about their appearance (A2), 59.18% at least agreed that their work has been impacted by vitiligo (A3), 46.62% had a feeling of being constantly watched (A5), and 55.31% and 51.64% believed that vitiligo brought financial burden (A6) and was a burden to their family (A7), respectively. Only 41.40% at least agreed that vitiligo cannot be cured (A4), and 39.26% believed that light therapy is more effective than drugs. The participants generally adhered to the physician’s strategy (86.07%) (P1). Still, non-negligible proportions of the participants reported not observing the adverse effects of treatments (49.12%) (P3), would choose traditional Chinese medicine (31.33%) (P4), would not undergo regular follow-up (30.55%), would not avoid sunlight (22.82%), would not exercise (19.34%), and would not communicate their experience with other patients (51.84%). (Supplementary Table 1).

Pearson correlation analysis

Pearson correlation analysis showed that the attitude was negatively correlated to the practice (r=−0.143, P = 0.001) (Table 2).

Mediation analysis

The mediation analysis showed that disease stage (β=−0.56, P < 0.001), residence (β = 0.50, P = 0.005), disease duration (β = 0.59, P < 0.001), education (β = 0.41, P < 0.001), age (β=−0.53, P < 0.001), and negative emotions (β = 0.47, P = 0.028) had direct effects on knowledge. Disease stage (β=−0.65, P < 0.001), income (β = 1.02, P < 0.001), type of work (β=−0.41, P = 0.037), and lesion location (β=−0.87, P < 0.001) had direct effects on attitude. Knowledge scores (β = 0.24, P = 0.023), attitude scores (β=−0.28, P < 0.001), disease duration (β=−1.49, P < 0.001), and negative emotions (β=−1.54, P = 0.008) had direct effects on practice. Income (β=−0.29, P = 0.003), disease duration (β = 0.16, P = 0.033), lesion duration (β = 0.25, P = 0.003), education (β = 0.11, P = 0.024), and age (β=−0.14, P = 0.036) had indirect effects on practice (Tables 3and Fig. 1). The model had a good fit, with all fit indexes meeting the criteria for goodness-of-fit (RMSEA = 0.000, SRMR = 0.015, TLI = 1.035, and CFI = 1.000) (Supplementary Table 2).

Mediation analysis. Ksum: knowledge scores; Asum: attitude scores; Psum: practice scores. The number in the Ksum, Asum, and Psum boxes are the coefficients of the KAP dimensions. The numbers in the factor boxes are the factor’s coefficient (top) and standard error (bottom). The numbers on the arrows are the β coefficients. The numbers beside the round boxes are the residual variance for each KAP dimension.

Discussion

This study found that vitiligo patients exhibited significant gaps in knowledge and attitude toward their disease despite active management practice. Knowledge scores, attitude scores, disease duration, and negative emotions had direct effects on practice. Income, disease duration, lesion duration, education, and age had indirect direct effects on practice.

A previous study in Turkey showed that patients with vitiligo displayed high knowledge of their disease27, while poorer knowledge was observed in the general population14,15,16,17,18. Two previous studies on the possible causes of vitiligo performed in patients with the disease revealed a low knowledge of the causes of vitiligo28,29. Poor knowledge in the general population is not surprising, but a low knowledge in diagnosed patients could be related to the benignity of vitiligo that mostly affects only the cosmetic appearance; many lesions can easily be hidden using clothes, leading to disinterest in the disease30, as shown by Topal et al.27, who reported that only 27% of the patients reported some impact of vitiligo on their lives.

The present study showed that the patients with vitiligo had poor knowledge of their disease. The patients’ knowledge in the present study was close to that of the general population, as reported in several studies14,15,16,17,18. In the present study, the mediation analysis showed that disease stage, residence, disease duration, education, age, and negative emotions directly influenced knowledge. Higher education is generally associated with higher health literacy31. Outdoor jobs are often manual jobs that are associated with a lower education requirement, which is associated with lower health literacy. Indoor jobs are more often liberal professions associated with stress, while outdoor jobs are associated with sunlight exposure. A longer history of vitiligo was associated with knowledge, probably because the patients had more time to experience progression and seek information. In addition, treatment duration influenced knowledge, probably because they cared about their appearance and the disease and were more actively seeking information. Negative emotions can incite the patients to consult more and obtain more information about their condition. Mental stress is publicly recognized to be associated with vitiligo despite inconsistent scientific evidence8,9,10. The study by Topal et al.27 in Turkey showed that 84%, 37%, 22%, and 20% of the participants reported stress, sunlight exposure, heredity, and excessive work as being the cause of vitiligo. Firooz et al.29 in Iran reported that 62.5% and 31.3% of their participants correctly identified stress and heredity as possible causes of vitiligo. AlGhamdi et al.28performed a study on Arabians and reported that most patients (84%) believed that fate was the cause of their disease. In the present study, only 57% of the participants responded correctly about the heredity of vitiligo, 3% about the infective nature of the disease, but 71% correctly identified stress as a possible trigger. Of note, 90% of the participants in two previous studies thought correctly that vitiligo was not contagious27,28. Nevertheless, the patient’s knowledge of vitiligo should be improved. The present study highlights that all aspects of vitiligo knowledge should be improved in patients in China.

Income had direct effects on attitude, probably due to better treatment access. Indeed, vitiligo treatments are considered esthetic and are not covered by many insurances, and some of them are expensive (e.g., calcineurin inhibitors and surgery)6,32,33,34. The type of work, lesion location, and disease stage all had direct influences on attitude. Disease progression can contribute to a sense of hopelessness and fatality toward the disease, leading to poor attitudes. Previous studies also reported poor attitudes regarding the effectiveness of the treatments27,28,29.

Attitude, disease duration, and negative emotions had direct influences on practice. Still, the present study was cross-sectional, and causality could not be determined. A long disease history could contribute to poor practice because of a feeling of helplessness because vitiligo cannot be cured and is unpredictable35.

It is generally considered that a higher level of knowledge will lead to better attitudes and practices. According to the KAP theory, knowledge is the basis for practice, and attitude is the force driving practice12,13. In the present study, the mediation analysis showed no association between knowledge and attitude, but knowledge influenced practice. Patients with vitiligo can suffer from major depressive disorders (36% of the patients), anxiety (24%), social phobia (19%), and sexual dysfunction (5%)36, and those factors can be greater barriers to attitudes and practice than knowledge. Still, those psychological factors (stress, anxiety, depression, social function, sexual function, and sleep disorders) were not examined in the present study. Future studies should examine these factors alongside KAP to examine possible correlations.

This study had some limitations. It was performed at only two centers in China, covering only a small proportion of the city and including a relatively small proportion of patients with vitiligo. The questionnaire was designed by the local investigators and, therefore, represents the local condition of vitiligo management, limiting the generalizability of the questionnaire. All KAP analyses are at risk of social desirability bias, in which individuals can be tempted to respond to what is generally accepted instead of what they do37,38. Finally, KAP surveys are cross-sectional studies, and the results represent a limited moment in time. In addition, causality cannot be determined using cross-sectional studies. A mediation analysis was performed as a surrogate of causality, but the results must be taken with caution since the causality is statistically inferred and based on predefined hypotheses rather than actually observed19,20,21. Nevertheless, the results could be used as a kind of baseline for the evaluation of future interventions.

Patients with vitiligo showed poor knowledge, suboptimal attitudes, and proactive practices, underscoring the need for tailored health education. The mediation analysis revealed that patients with progressive disease, longer disease duration, and lesions in exposed areas require prioritized interventions to enhance knowledge and attitudes. Factors such as lower education, younger age, and lower income were also indirectly linked to suboptimal practices, highlighting the importance of targeted strategies for these groups. Education focused on avoiding triggers (e.g., stress, sun exposure) and adopting proper habits can improve disease management and quality of life.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Yaghoobi, R., Omidian, M. & Bagherani, N. Vitiligo: a review of the published work. J. Dermatol. 38, 419–431 (2011).

Tang, L. et al. Prevalence of vitiligo and associated comorbidities in adults in Shanghai, China: a community-based, cross-sectional survey. Ann. Palliat. Med. 10, 8103–8111 (2021).

Vrijman, C. et al. Provoking factors, including chemicals, in Dutch patients with vitiligo. Br. J. Dermatol. 168, 1003–1011 (2013).

Lee, J. H. et al. Treatment outcomes of topical calcineurin inhibitor therapy for patients with Vitiligo: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 155, 929–938 (2019).

Lim, H. W. et al. Afamelanotide and narrowband UV-B phototherapy for the treatment of vitiligo: a randomized multicenter trial. JAMA Dermatol. 151, 42–50 (2015).

Rosmarin, D. et al. Two phase 3, Randomized, controlled trials of ruxolitinib cream for Vitiligo. N Engl. J. Med. 387, 1445–1455 (2022).

Whitton, M. E. et al. Interventions for vitiligo. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. CD003263 (2015).

Henning, S. W. et al. The relationship between stress and vitiligo: evaluating perceived stress and electronic medical record data. PLoS One. 15, e0227909 (2020).

Litaiem, N., Charfi, O., Ouanes, S., Gara, S. & Zeglaoui, F. Patients with vitiligo have a distinct affective temperament profile: a cross-sectional study using temperament evaluation of Memphis, Paris, and San Diego Auto-Questionnaire. Skin. Health Dis. 3, e157 (2023).

Picardi, A. et al. Stressful life events, social support, attachment security and alexithymia in vitiligo. A case-control study. Psychother. Psychosom. 72, 150–158 (2003).

Taieb, A. et al. Guidelines for the management of vitiligo: the European Dermatology Forum consensus. Br. J. Dermatol. 168, 5–19 (2013).

World Health Organization. Advocacy, communication and social mobilization for TB control: a guide to developing knowledge, attitude and practice surveys. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596176_eng.pdf. Accessed November 22, 20222008.

Andrade, C., Menon, V., Ameen, S. & Kumar Praharaj, S. Designing and conducting knowledge, attitude, and practice surveys in Psychiatry: practical Guidance. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 42, 478–481 (2020).

Juntongjin, P., Rachawong, C. & Nuallaong, W. Knowledge and attitudes towards vitiligo in the general population: a survey based on the simulation video of a real situation. Derm Sinica. 36, 75–78 (2018).

Alghamdi, K. M. et al. Public perceptions and attitudes toward vitiligo. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 16, 334–340 (2012).

Fatani, M. I., Aldhahri, R. M., Al Otaibi, H. O. & Kalo, B. B. Khalifa M. A. Acknowledging popular misconceptions about vitiligo in western Saudi Arabia. J. Dermatol. Dermatol. Surg. 20, 27–31 (2016).

Asati, D. P., Gupta, C. M., Tiwari, S., Kumar, S. & Jamra, V. A hospital-based study on knowledge and attitude related to vitiligo among adults visiting a tertiary health facility of central India. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 7, 27–32 (2016).

Tsadik, A. G., Teklemedhin, M. Z., Atey, T. M., Gidey, M. T. & Desta, D. M. Public knowledge and attitudes towards Vitiligo: a Survey in Mekelle City, Northern Ethiopia. Demtatol Res. Pract. 3495165 (2020).

Beran, T. N. & Violato, C. Structural equation modeling in medical research: a primer. BMC Res. Notes. 3, 267 (2010).

Fan, Y., Chen, J. & Shirkey, G. Applications of structural equation modeling (SEM) in ecological studies: an updated review. Ecol. Process. 5, 19 (2016).

Kline, R. B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (Fifth Edition) (The Guilford Press, 2023).

Lei, T. C. et al. Consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of Vitiligo in China (2021 revision). Intl Dermatol. Venereol. 4, 10–15 (2021).

Lee, F. & Suryohusodo, A. A. Knowledge, attitude, and practice assessment toward COVID-19 among communities in East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia: a cross-sectional study. Front. Public. Health. 10, 957630 (2022).

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J. & Mullen, M. Structural equation modeling: guidelines for determining Model Fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 6. (2007).

Wen, Z., Hau, K. T. & Marsh, H. Structural equation model testing: cutoff criteria for goodness of fit indices and chi-square test. Acta Physiol. Sinica. 36, 186–194 (2004).

Sathyanarayana, S. & Mohanasundaram, T. Fit indices in Structural Equation Modeling and confirmatory factor analysis: reporting guidelines. Asian J. Econom Busin Acc. 24, 561–577 (2024).

Topal, I. O. et al. Knowledge, beliefs, and perceptions of Turkish vitiligo patients regarding their condition. Bras. Dermatol. 91, 770–775 (2016).

AlGhamdi, K. M. Beliefs and perceptions of arab vitiligo patients regarding their condition. Int. J. Dermatol. 49, 1141–1145 (2010).

Firooz, A. et al. What patients with vitiligo believe about their condition. Int. J. Dermatol. 43, 811–814 (2004).

Tarle, R. G., Nascimento, L. M. & Mira, M. T. Castro C. C. Vitiligo–part 1. Bras. Dermatol. 89, 461–470 (2014).

Jansen, T. et al. The role of health literacy in explaining the association between educational attainment and the use of out-of-hours primary care services in chronically ill people: a survey study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 18, 394 (2018).

Dillon, A. B., Sideris, A., Hadi, A. & Elbuluk, N. Advances in Vitiligo: an update on Medical and Surgical treatments. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 10, 15–28 (2017).

Matsuzaki, K. & Kumagai, N. Treatment of vitiligo with autologous cultured keratinocytes in 27 cases. Eur. J. Plast. Surg. 36, 651–656 (2013).

Su, X. et al. Efficacy and tolerability of oral upadacitinib monotherapy in patients with recalcitrant vitiligo. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 89, 1257–1259 (2023).

Grimes, P. E., Miller, M. M. & Vitiligo Patient stories, self-esteem, and the psychological burden of disease. Int. J. Womens Dermatol. 4, 32–37 (2018).

Ahmed, I., Ahmed, S. & Nasreen, S. Frequency and pattern of psychiatric disorders in patients with vitiligo. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad. 19, 19–21 (2007).

Bergen, N. & Labonte, R. Everything is perfect, and we have no problems: detecting and limiting Social Desirability Bias in qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 30, 783–792 (2020).

Latkin, C. A., Edwards, C., Davey-Rothwell, M. A. & Tobin, K. E. The relationship between social desirability bias and self-reports of health, substance use, and social network factors among urban substance users in Baltimore, Maryland. Addict. Behav. 73, 133–136 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the help of Tao Wang (Department of Dermatology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital) and Guilan Yang (Department of Dermatology, Shenzhen Hospital of Southern Medical University).

Funding

The study was supported by the Scientific Research Project of the Chinese Research Hospital Society (Y2021FH-PFK06).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HF carried out the studies, participated in collecting data, and drafted the manuscript. HF and SXS performed the statistical analysis and participated in its design. XLX, SZQ, KC, MJ, and XFL participated in the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, and the Medical Ethics Committee of Dermatology Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (approval # KY2022-188-02 and 2022-KY-070, respectively). All participants provided written informed consent before completing the survey. I confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines. All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, H., Xu, X., Qi, S. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice toward vitiligo among vitiligo patients: a mediation analysis. Sci Rep 15, 4741 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89346-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89346-w