Abstract

The role of diet in reducing the burden of liver disease and mortality attributed to cirrhosis is very imperative. The present study scrutinized the relationship between dietary advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and mortality in patients with cirrhosis. This research was a prospective cohort study on 166 ambulatory cirrhotic patients who had been diagnosed with cirrhosis for a maximum of six months. Follow-up of patients continued for 5 years until May 2024. To determine the incidence of mortality in the quartiles of dietary AGEs, cox regression models were used with the adjustment of potential confounding variables. Although the first model of the analysis by adjusting the results for age and sex failed to show a significant increase in the risk of mortality in patients (HRQ4 vs. Q1 = 2.64; 95% CI = 0.9–7.5, P trend = 0.075), after adjusting the results for further confounders in the second (HRQ4 vs. Q1 = 3.56; 95% CI = 1.1–11.6, P trend = 0.040) and third (HRQ4 vs. Q1 = 3.3; 95% CI = 1.79–13.7, P trend = 0.048) models, the P trend for the risk of mortality during the quartiles of AGEs became significant. In addition, along with increasing trend of dietary AGEs, the number of deaths increased significantly (P = 0.024). Higher mortality risk was generally attributed to higher dietary AGEs in patients with cirrhosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Liver cirrhosis plays a major role in the morbidity and mortality of patients with chronic liver diseases1. Cirrhosis involves stages of progressive liver damage characterized by the extensive formation of fibrous tissue that transforms the lobular structure of the liver into regenerative nodules2. This process significantly impairs liver function2. Cirrhosis can lead to the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and hepatic decompensation, which includes conditions like ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and variceal bleeding1,3,4,5,6,7,8. Cirrhosis is one of the main causes of global mortality, accounting for 2.4% of global deaths in 20199. Moreover, the burden of disease project in Iran in 2017 showed that cirrhosis and other liver diseases accounted for 1.42% of the total mortality rate10.

Cirrhosis has been associated with various factors including viral infections, autoimmune disorders, metabolic and genetic disorders, long-term use of some drugs11, alcohol abuse12, and diabetes mellitus (DM)13,14. In addition to the mentioned factors, diet is also considered as an operative factor in the etiology of liver cirrhosis15. The modern dietary patterns contain highly processed foods, which are not only high in fat, sugar, and salt, but also contain potentially harmful compounds known as advanced glycation end-products (AGEs). Previous studies have revealed that dietary AGEs are directly related to increased inflammation, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance (IR)16,17. Therefore, dietary AGEs play an important role in the pathogenesis of diseases18.

AGEs are formed through a non-enzymatic reaction where reducing sugars chemically interact with amino groups found in proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. This sequence includes creating a Schiff base, an Amadori rearrangement, and oxidative modifications (glycoxidation), leading to the production of AGEs19,20,21. AGEs are produced by two main processes: one is the natural metabolic processes of the body and the other is the formation of AGEs that occurs during cooking and food processing. A significant part of these AGEs are absorbed by the digestive system22.

Direct association of AGEs with increased risk of many chronic diseases such as diabetes and its related complications, cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), obesity, kidney and neurological diseases has been proven23. Also, it has been reported that non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and cirrhosis are associated with increased serum concentrations of N-carboxyethyllysine (CEL) and N-carboxymethyllysine (CML)24. There is a growing body of evidence linking AGEs to intimal thickening, plaque formation, and ultimately the development or progression of atherosclerosis, which predisposes to cardiovascular events25, which in turn are a major cause of mortality in patients with cirrhosis26. Advanced glycation end products may cause the production of oxygen free radicals through interaction with receptors involved in inflammation signaling, followed by the release of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP) in various cells, especially the liver24. Although the exact mechanism of the development and progression of cirrhosis is still not fully understood, growing evidence suggests that AGEs may play a role in the development of the disease and exacerbation of its complications by stimulating inflammation.

In our current study, we hypothesized that dietary AGEs may promote inflammatoty cascade seen in cirrhotic patients, subsequently leading to high rate of mortality. Therefore in present prospective cohort study, we investigated the relationship between dietary AGEs and mortality in patients with cirrhosis.

Methods and materials

Study design and population

The current cohort study included 166 adult patients with liver cirrhosis, aged over 18 years who had been diagnosed within the past 6 months. The methods of this research have been described in detail elsewhere27,28, with the difference that the follow-up period in this study was 60 months.

Briefly, non-pregnant or lactating patients with no medical history of diseases such as renal failure, cancer, diabetes, infectious diseases, heart disease, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), or pancreatic insufficiency were included in this study. In this study, the participants were followed up for 5 years from the time of registration. They were contacted annually by telephone to complete a follow-up questionnaire regarding any deaths or medical events.

Dietary assessment and AGEs calculation

Dietary intakes were collected through face-to-face interviews using a reliable and valid food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) with 168 items29 at enrollment, before disease diagnosis had significant effects on patients’ intakes. A trained nutritionist assessed and analyzed dietary data using Nutritionist IV software. Information on the consumption of different food items was recorded on a daily, weekly and monthly basis and subsequently converted to grams using standard household measurements. The average daily consumption of energy and essential nutrients was determined by utilizing the food composition table (FCT) provided by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Since the Iranian food composition table does not have data on the content of AGEs in foods, to calculate the intake of dietary AGEs, we used the published database of food AGEs for a multi-ethnic urban population in the northeastern United States, which was measured using a valid immunoassay method30,31. Considering that the FFQ questions were designed based on the frequency of consumption and the usual size of food, first the consumed food items reported in household measures were converted to grams, then the total consumption of AGEs per day was calculated for each participant. For data analysis, consumption was classified using quartile cutoffs. The intake of AGEs was adjusted for daily energy intake.

Other assessments

Basic information such as age, sex, alcohol and smoking habits and the cause of cirrhosis were collected as primary data at the beginning of the study. Weight was accurately measured using digital scales, rounded to the nearest 100 g, while height was measured with a tape measure to the closest 1 cm. These measurements were taken while the participants were wearing light cloths and standing straight without shoes. Subsequently, the BMI was calculated by dividing the weight in kilograms by the square of the height in meters.

The subjective global assessment (SGA) score was calculated based on Destky et al.32. Accordingly, participants were divided into three categories including well-nourished (A), mild to moderate malnourished (B), and severe malnourished (C). Severity and prognosis of liver cirrhosis were evaluated by using clinical and biochemical indicators and determination of Child-Pugh (qualitative: A,B and C) and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores (quantitative)33.

Statistical analysis

To perform comparisons and analyses, participants were divided into four quartiles based on their dietary intake of AGEs. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or chi-square (χ2) test was used to compare baseline characteristics and dietary intakes of participants among quartiles of AGEs, as desired. Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression models to assess the relationship between dietary intakes of AGEs and mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Three different models were designed to control the potential confounding variables. Model 1: adjustments for sex (man, woman) and age (continuous). Model 2: additionally adjustments for BMI, alcohol consumption (> 30 g/day), and smoking habits. Model 3: additionally adjustments for Child-Pugh classification, MELD score, and etiology of liver disease. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 19; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) with a significance level of < 0.05.

Results

The final analysis was conducted on a total of 121 participants (83 men and 38 women). During the 5 years of follow-up, 50 deaths were recorded. Liver failure accounted for 55% of deaths, cardiovascular diseases 31%, carcinoma 3% and miscellaneous causes for 11% of deaths. The average intake of AGEs was estimated as 8427.6 ± 5114 mg/day. As Table 1 shows, the ratio of men to women increases significantly as the average intake of dietary AGEs increases (P = 0.006). Also, smoking (P = 0.017) and alcohol use (P = 0.032) increased significantly. Although most cases of cirrhosis had a viral cause, the etiology difference between the AGE quartiles was close to the significant level (P = 0.047). No significant differences were observed in the participants’ average age, anthropometric and clinical parameters.

As presented in Table 2, comparison of dietary intakes among AGE quartiles indicated a significant increase in energy intake (P = 0.016) and meats (P = 0.001). While the decrease in the percentage of carbohydrates from the total energy intake was close to a significant level (P = 0.052). No significant differences were observed between other dietary intakes aross the AGE quadrtiles.

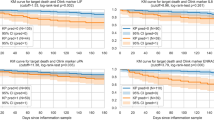

The results of the analysis of the relationship between dietary intakes of AGEs and mortality in patients with cirrhosis are summarized in Table 3. Although the first model of the analysis by adjusting the results for age and sex failed to show a significant increase in the risk of mortality in patients (HRQ4 vs. Q1 = 2.64; 95% CI = 0.9–7.5, P trend = 0.075), after adjusting the results for further confounders in the second (HRQ4 vs. Q1 = 3.56; 95% CI = 1.1–11.6, P trend = 0.040) and third (HRQ4 vs. Q1 = 3.3; 95% CI = 1.79–13.7, P trend = 0.048) models, the P trend for the risk of mortality during the quartiles of AGEs became significant. In addition, along with increasing trend of dietary AGEs, the number of deaths increased significantly (P = 0.024). Full adjusted hazard ratios for mortality in patients with cirrhosis in different quartiles of AGEs are depited in Fig. 1.

Discussion

This cohort study contributed to the expansion of knowledge about the possible association between dietary AGEs and mortality in patients with cirrhosis. What emerges from the results of this cohort is an increase in the risk of mortality by 2–3 times following an increase in AGE intake in cirrhotic patients. These findings are consistent with some previous studies that indicated the relationship between AGE intake and mortality in patients with various chronic diseases. A follow-up of postmenopausal women diagnosed with breast cancer for more than 15 years showed that a high intake of AGEs was associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality, CVD, and breast cancer34. Similarly, a direct association of serum AGEs with increased risk of mortality of all-caused, CVD, and coronary heart disease was also reported in a large cohort study with more than 1100 participants35. However, conflicting results have been reported in some studies36,37,38.

Cirrhosis commonly coexists with inflammation, insulin resistance (IR) and related complications such as metabolic syndrome (MetS) which could provide an explanation for the association between AGEs and liver cirrhosis39,40, although the exact mechanism of this association has not yet been fully elucidated. Recent findings have confirmed that the interaction between AGEs and their cellular receptor (RAGE) may play a role in developing various severe conditions, including diabetic vascular problems, neurodegenerative disorders, IR, and cancers41,42,43,44,45,46,47. Moreover, a growing body of evidence suggests that the interaction between AGEs and RAGE elicits reactive oxygen species (ROS) and subsequently leads to inflammatory responses in different cell types, such as hepatocytes and hepatic stellate cells48,49,50,51. AGEs activate Kupffer cells, sinusoidal endothelial cells, and stellate cells, resulting in the release of oxygen radicals and cytokines like transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, which promotes fibrosis52. Furthermore, AGEs can directly contribute to increased collagen deposition in the liver through cross-link formation52.

According to the findings of the present study, comparing the highest intake with the lowest quartile after adjusting for confounding factors, the dietary intake of AGEs was associated with a more than 3-fold increase in the risk of mortality in cirrhotic patients, and on the other hand, the main cause of death of patients in this study was liver failure (55%), which can be caused by AGE damage to the hepatic tissue. Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) play a crucial role in liver fibrogenesis by producing an extracellular matrix in the liver50. Fehrenbach et al.50showed that HSCs and myofibroblasts (MFB) can express RAGE, and the activation of HSCs and their differentiation to MFB increases RAGE expression. Activation of RAGE by ligands resulted in the generation of ROS and the initiation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathways HSCs, which are directly related to hepatic inflammation50,53,54. Moreover, AGEs derived from glyceraldehyde stimulate the expression of fibrosis and inflammation-related genes and proteins, such as TGF-β1, collagen type I alpha2, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, by generating ROS via NADPH oxidase in cultured HSCs51. The interaction between AGEs and RAGE triggers the activation of Rac-1, leading to the stimulation of hepatic CRP in human hepatoma cells, specifically Hep3B cells55. Previous studies have indicated that at least two separate signaling pathways contribute to the induction of the CRP gene in Hep3B cells exposed to AGEs. One pathway involves the activation of Rac-1 and the NADPH oxidase, leading to the production of ROS. Rac-1 mediates the other pathway and involves the activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and NF-κB, but does not directly rely on ROS55. IR is another possible mechanism that explains the association between AGEs and cirrhosis. AGEs play a role in hepatic IR by causing the phosphorylation of IRS-1 at serine residues through the activation of JNK and IκB kinase, which was mediated by Rac-1 activation55. CVD was another major cause of mortality in this study, and previous studies have proven the relationship of CVD with AGEs and suggested similar mechanisms for it56,57,58.

To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first to investigate the relationship between dietary intake of AGEs and the risk of mortality in patients with cirrhosis, which was one of the strengths of this study. In addition, an attempt was made to increase the reliability of the study by adjusting all potential confounding factors. However, the current study has limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results, including small sample size and potential recall bias in the use of the FFQ. Also, the selection of confounding factors was based on prior knowledge, existing literature and clinical considerations. Therefore, similar to numerous observational studies, the outcomes may have been affected by residual and unmeasured confounding.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings emphasize that higher intake of AGEs does increase the chance of mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Further studies are necessary to clarify the underlying mechanisms of this relationship.

Data availability

The datasets analysed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

GinËs, P. et al. Liver Cirrhosis Lancet ;398(10308):1359–1376. (2021).

Garcia-Tsao, G., Friedman, S., Iredale, J. & Pinzani, M. Now there are many (stages) where before there was one: in search of a pathophysiological classification of cirrhosis. Hepatology 51 (4), 1445–1449 (2010).

Tapper, E. B., Ufere, N. N., Huang, D. Q. & Loomba, R. Current and emerging therapies for the management of cirrhosis and its complications. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 55 (9), 1099–1115 (2022).

Tapper, E. B. & Parikh, N. D. Mortality due to cirrhosis and liver cancer in the United States, 1999–2016: observational study. Bmj ;362. (2018).

Huang, D. Q. et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in alcohol-associated cirrhosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21 (5), 1169–1177 (2023).

Tan, D. J. H. et al. Clinical characteristics, surveillance, treatment allocation, and outcomes of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 23 (4), 521–530 (2022).

Tan, D. J. H. et al. Global burden of liver cancer in males and females: changing etiological basis and the growing contribution of NASH. Hepatology 77 (4), 1150–1163 (2023).

Ajmera, V. et al. Liver stiffness on magnetic resonance elastography and the MEFIB index and liver-related outcomes in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participants. Gastroenterology 163 (4), 1079–1089 (2022). e5.

Huang, D. Q. et al. Global epidemiology of cirrhosis—aetiology, trends and predictions. Nat. Reviews Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 20 (6), 388–398 (2023).

Anushiravani, A. & Sepanlou, S. G. Burden of liver diseases: a review from Iran. Middle East. J. Dig. Dis. 11 (4), 189 (2019).

Kamath, P. S. & Shah, V. H. Overview of Cirrhosis. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease 10th edn 1254–1260 (Saunders Inc, 2016).

Rehm, J. et al. Alcohol as a risk factor for liver cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Rev. 29 (4), 437–445 (2010).

Garcia-Compean, D., Jaquez-Quintana, J. O., Gonzalez-Gonzalez, J. A. & Maldonado-Garza, H. Liver cirrhosis and diabetes: risk factors, pathophysiology, clinical implications and management. World J. Gastroenterology: WJG. 15 (3), 280 (2009).

García-Compeán, D. et al. The prevalence and clinical characteristics of glucose metabolism disorders in patients with liver cirrhosis. A prospective study. Ann. Hepatol. 11 (2), 240–248 (2012).

Ioannou, G. N., Morrow, O. B., Connole, M. L. & Lee, S. P. Association between dietary nutrient composition and the incidence of cirrhosis or liver cancer in the United States population. Hepatology 50 (1), 175–184 (2009).

Kellow, N. J. & Savige, G. S. Dietary advanced glycation end-product restriction for the attenuation of insulin resistance, oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction: a systematic review. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 67 (3), 239–248 (2013).

Van Puyvelde, K., Mets, T., Njemini, R., Beyer, I. & Bautmans, I. Effect of advanced glycation end product intake on inflammation and aging: a systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 72 (10), 638–650 (2014).

Clarke, R. E., Dordevic, A. L., Tan, S. M., Ryan, L. & Coughlan, M. T. Dietary Advanced Glycation End products and Risk factors for chronic disease: a systematic review of Randomised controlled trials. Nutrients 8 (3), 125 (2016).

Pérez-Burillo, S., Rufián-Henares, J. Á. & Pastoriza, S. Effect of home cooking on the antioxidant capacity of vegetables: relationship with Maillard reaction indicators. Food Res. Int. 121, 514–523 (2019).

Reddy, V. P. & Beyaz, A. Inhibitors of the Maillard reaction and AGE breakers as therapeutics for multiple diseases. Drug Discovery Today. 11 (13–14), 646–654 (2006).

Van Nguyen, C. Toxicity of the AGEs generated from the Maillard reaction: on the relationship of food-AGEs and biological‐AGEs. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 50 (12), 1140–1149 (2006).

Sergi, D., Boulestin, H., Campbell, F. M. & Williams, L. M. The role of dietary advanced glycation end products in metabolic dysfunction. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 65 (1), 1900934 (2021).

Bernhard, W. et al. Dietary sugar is critical for high fat diet-induction of hypothalamic inflammation via advanced glycation end-products. Mol. Metab. 6, 897–908 (2017).

Litwinowicz, K., Waszczuk, E. & Gamian, A. Advanced glycation end-products in common non-infectious liver diseases: systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 13 (10), 3370 (2021).

Peppa, M., Uribarri, J. & Vlassara, H. The role of advanced glycation end products in the development of atherosclerosis. Curr. Diab. Rep. 4 (1), 31–36 (2004).

Cesari, M., Frigo, A. C., Tonon, M. & Angeli, P. Cardiovascular predictors of death in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 68 (1), 215–223 (2018).

Daftari, G. et al. Dietary protein intake and mortality among survivors of liver cirrhosis: a prospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 23 (1), 227 (2023).

Pashayee-Khamene, F. et al. Dietary acid load and cirrhosis-related mortality: a prospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 3675 (2024).

Mirmiran, P., Esfahani, F. H., Mehrabi, Y., Hedayati, M. & Azizi, F. Reliability and relative validity of an FFQ for nutrients in the Tehran lipid and glucose study. Public Health. Nutr. 13 (5), 654–662 (2010).

Uribarri, J. et al. Advanced glycation end products in foods and a practical guide to their reduction in the diet. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 110 (6), 911–916 (2010). e12.

Goldberg, T. et al. Advanced glycoxidation end products in commonly consumed foods. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 104 (8), 1287–1291 (2004).

Detsky, A. S. JR, Baker, M., Johnston, J. P., Whittaker, N. & Mendelson, S. What is subjective global assessment of nutritional status? J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 11 (1), 8–13 (1987).

Malinchoc, M. et al. A model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology 31 (4), 864–871 (2000).

Omofuma, O. O. et al. Dietary advanced glycation end-products and mortality after breast cancer in the women’s health initiative. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 30 (12), 2217–2226 (2021).

Kilhovd, B. K. et al. High serum levels of advanced glycation end products predict increased coronary heart disease mortality in nondiabetic women but not in nondiabetic men: a population-based 18-year follow-up study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25 (4), 815–820 (2005).

Nongnuch, A. & Davenport, A. Skin autofluorescence advanced glycosylation end products as an independent predictor of mortality in high flux haemodialysis and haemodialysis patients. Nephrology 20 (11), 862–867 (2015).

Gerrits, E. G. et al. Skin autofluorescence: a pronounced marker of mortality in hemodialysis patients. Nephron Extra. 2 (1), 184–191 (2012).

Mukai, H. et al. Skin autofluorescence, arterial stiffness and Framingham risk score as predictors of clinical outcome in chronic kidney disease patients: a cohort study. Nephrol. Dialysis Transplantation. 34 (3), 442–448 (2019).

Davis, K. E., Prasad, C., Vijayagopal, P., Juma, S. & Imrhan, V. Advanced glycation end products, inflammation, and chronic metabolic diseases: links in a chain? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 56 (6), 989–998 (2016).

Unoki, H. & Yamagishi, S. Advanced glycation end products and insulin resistance. Curr. Pharm. Design. 14 (10), 987–989 (2008).

Yamagishi, S., Takeuchi, M., Inagaki, Y., Nakamura, K. & Imaizumi, T. Role of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and their receptor (RAGE) in the pathogenesis of diabetic microangiopathy. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Res. 23 (4), 129–134 (2003).

Takeuchi, M. & Yamagishi, S. TAGE (toxic AGEs) hypothesis in various chronic diseases. Med. Hypotheses. 63 (3), 449–452 (2004).

Takeuchi, M. & Yamagishi, S. Alternative routes for the formation of glyceraldehyde-derived AGEs (TAGE) in vivo. Med. Hypotheses. 63 (3), 453–455 (2004).

Tesařová, P. et al. Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE)—soluble form (sRAGE) and gene polymorphisms in patients with breast cancer. Cancer Invest. 25 (8), 720–725 (2007).

Riuzzi, F., Sorci, G. & Donato, R. RAGE expression in rhabdomyosarcoma cells results in myogenic differentiation and reduced proliferation, migration, invasiveness, and tumor growth. Am. J. Pathol. 171 (3), 947–961 (2007).

Kuniyasu, H., Chihara, Y. & Kondo, H. Differential effects between amphoterin and advanced glycation end products on colon cancer cells. Int. J. Cancer. 104 (6), 722–727 (2003).

Takeuchi, M. et al. Involvement of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 1 (1), 39–46 (2004).

Ekong, U. et al. Blockade of the receptor for advanced glycation end products attenuates acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21 (4), 682–688 (2006).

Yoshida, T. et al. Telmisartan inhibits AGE-induced C-reactive protein production through downregulation of the receptor for AGE via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activation. Diabetologia 49, 3094–3099 (2006).

Fehrenbach, H., Weiskirchen, R., Kasper, M. & Gressner, A. M. Up-regulated expression of the receptor for advanced glycation end products in cultured rat hepatic stellate cells during transdifferentiation to myofibroblasts. Hepatology 34 (5), 943–952 (2001).

Iwamoto, K. et al. Advanced glycation end products enhance the proliferation and activation of hepatic stellate cells. J. Gastroenterol. 43, 298–304 (2008).

Šebeková Kn, Kupčová, V., Schinzel, R. & Heidland, A. Markedly elevated levels of plasma advanced glycation end products in patients with liver cirrhosis–amelioration by liver transplantation. J. Hepatol. 36 (1), 66–71 (2002).

Westenberger, G. et al. Function of mitogen-activated protein kinases in hepatic inflammation. J. Cell. Signal. 2 (3), 172 (2021).

Heyninck, K., Wullaert, A. & Beyaert, R. Nuclear factor-kappa B plays a central role in tumour necrosis factor-mediated liver disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 66 (8), 1409–1415 (2003).

Yoshida, T. et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) inhibits advanced glycation end product (AGE)-induced C-reactive protein expression in hepatoma cells by suppressing Rac-1 activation. FEBS Lett. 580 (11), 2788–2796 (2006).

Hegab, Z., Gibbons, S., Neyses, L. & Mamas, M. A. Role of advanced glycation end products in cardiovascular disease. World J. Cardiol. 4 (4), 90 (2012).

Peppa, M. & Raptis, S. A. Advanced glycation end products and cardiovascular disease. Curr. Diabetes. Rev. 4 (2), 92–100 (2008).

Rojas, A., Mercadal, E., Figueroa, H. & Morales, M. A. Advanced Glycation and ROS: a link between diabetes and heart failure. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 6 (1), 44–51 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This study is related to the project from Student Research Committee, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. We also appreciate the “Student Research Committee” and “Research & Technology Chancellor” in Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences for their financial support of this study.

Funding

This project was funded by grant from Student Research Committee, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. The funding body has no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, ZY and AH; Formal analysis, ZY and ZM; Methodology, MS, FPK, BH, SA and SK; Project administration, MST, MN and AH; Writing – original draft, MST, MN and ZY; Writing – review & editing, ZY and AH. All authors read and approved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

National nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute (NNFTRI) ethics committee approved the study protocol (IR. SBMU. NNFTRI.1396.186) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent and were informed about the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tabar, M.S., Nilghaz, M., Hekmatdoost, A. et al. Advanced glycation end products and risk of mortality in patients with cirrhosis: a prospective cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 4798 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89433-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89433-y