Abstract

Caregivers to stroke survivors often experience a multifaceted strain defined as caregiver burden. Low health literacy among caregivers may contribute to increased caregiver burden but there is limited research specifically examining the association between stroke survivors’ health literacy and caregiver burden. Therefore, the aim here is to explore if there is an association between stroke survivors’ health literacy and caregiver burden one year after stroke. Participants were 50 caregivers and 50 stroke survivors who were followed up in a longitudinal study on care transitions after stroke. Data were collected one year after the stroke survivors’ discharge from hospital and analysed using ordinal logistic regression. Most of the caregivers, median age 71 years, reported being satisfied with their lives (85%) and a low caregiver burden (74%). Stroke survivors’ health literacy was not associated with caregiver burden. However, lower needs of assistance in daily activities, lower levels of depression, higher levels of participation and increased age in stroke survivors were associated with lower caregiver burden. In conclusion, stroke survivors’ health literacy was not associated with caregiver burden one year after stroke. Future studies with larger samples, focusing on populations with lower functioning after stroke and higher caregiver burden, are recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

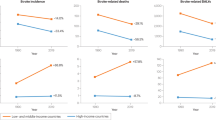

Stroke is the second leading cause of death worldwide, with incidence increasing with age1,2. Long-term consequences after stroke, such as sensorimotor and cognitive disabilities1, are common, and these require rehabilitation and ongoing support from caregivers such as family members3.

Being a caregiver has been described as a full-time job and may impact various aspects of the caregivers’ life such as their own well-being, participation in activities, and the relationship with the care recipient4. Caregivers may experience multifaceted strain defined as caregiver burden5, significantly impacting their health and well-being6. The prevalence of caregivers experiencing a significant burden ranges from 25 to 54%, with some studies suggesting variation over time7. A previous study found that 32% experience a high caregiver burden at some point in the first year after the care recipient’s stroke, and high caregiver burden is associated with living together with the stroke survivor8.

Both factors associated with the caregiver and factors associated with the stroke survivor may increase caregiver burden. Factors related to the caregiver include spending more time on caregiving, experiencing mental health problems, reporting unmet needs, and having low life satisfaction9,10,11. Low levels of participation among stroke survivors are also associated with increased caregiver burden12,13. Further, higher caregiver burden can in turn contribute to higher anxiety and depression symptoms, as well as a poorer sense of coherence in caregivers9,14. There are conflicting results in the literature regarding the care recipient’s age and its impact on caregiver burden11. However, evidence seems consistent regarding the association between higher caregiver burden and care recipients’ low levels of global functioning; higher dependency in activities of daily living; impaired motor function; poor neuropsychological status and cognitive functioning; and mental health issues11,14,15,16.

Health literacy refers to an individual’s ability to “gain access to, understand and use information in ways which promote and maintain good health”, enabling effective engagement and informed health decision-making17,18. It is associated with better function and overall health among stroke survivors19,20. For people with Parkinson’s disease, low health literacy was associated with higher caregiver burden when not taking disease severity and cognitive impairment into account21. In other populations, the association between health literacy among caregivers and caregiver burden has been investigated. A systematic review indicated that low health literacy among caregivers may contribute to increased caregiver burden and poorer care recipient self-management behaviours22, and interventions increasing health literacy can reduce caregiver burden23.

While the relationship between caregivers’ health literacy and caregiver burden has been explored22, we have found no research specifically examining the association between stroke survivors’ health literacy and caregiver burden. This association is important to study as it is plausible that stroke survivors with high literacy are less dependent on their caregivers in managing their health. This knowledge could contribute to the development of targeted interventions aimed at reducing caregiver burden and enhancing the overall well-being of stroke survivors and their caregivers.

Aim

The aim of the study was to explore if there is an association between stroke survivors’ health literacy and caregiver burden one year after stroke.

Methods

Study design

The study had a cross-sectional design and used an explorative approach.

Study participants

A longitudinal study investigating care transitions in stroke survivors was carried out between 2016 and 2018. Detailed information on recruitment and data collection has previously been described24,25. In brief, patients with a suspected diagnosis of stroke who were referred to neurorehabilitation teams in primary care after discharge from one of two participating hospitals in the Stockholm region and their significant others were included in the study. Patients were recruited by members of the rehabilitation teams working at participating hospitals. Significant others of the included patients were also invited to participate. All participants received oral and written information about the study. Inclusion took place after a signed informed consent was obtained. Participants in the present study were those who participated in the one-year follow-up and completed the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (stroke survivors) and the Caregiver Burden Scale (their significant others, hereafter named caregivers).

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Stockholm (registration number 2015/1923–31/2) and is reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines. All research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data collection

Data were collected from stroke survivors and caregivers. Sociodemographic data from stroke survivors were retrieved from medical records, questionnaires, and from caregivers through questionnaires. Data included age, sex, cohabiting status (yes/no) and relationship between stroke survivor and caregivers. Further, from stroke survivors, data on educational level (elementary, secondary, university/college), and working status (yes/no) were collected. From caregivers, data on assisting the stroke survivor with personal activities of daily living (P-ADL) (yes/no), and with instrumental activities of daily living (I-ADL) (yes/no), were collected.

A single item of The Life Satisfaction Questionnaire was used to assess overall life satisfaction in caregivers26. The scale ranges from 1 (very unsatisfied) to 6 (very satisfied)27. In the analysis, the scale was dichotomised into not satisfied (1–4) and satisfied (5–6).

Cognitive impairment among the stroke survivors was assessed using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Lower scores (< 26 points of max 30) indicate cognitive impairment28.

Outcome variable

Caregiver burden was assessed with the Caregiver Burden Scale. The questionnaire consists of 22 items regarding perceived burden as a caregiver to a person with disability29. The items can be rated from 1 to 4 (not at all, seldom, sometimes, often), and cover aspects such as caregivers’ health, psychological well-being, relations and social network, physical workload, and aspects related to environment. The severity of the burden was classified according to the mean scores as follows: 1.00-1.99 (low burden), 2.00-2.99 (moderate burden), and 3.00-3.99 (high burden).

Independent variables related to stroke survivors

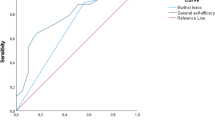

Stroke survivors’ health literacy was assessed using the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire30. It consists of 16 items and comprises four dimensions of health literacy: the ability to access, understand, process, and apply health information31. The total score ranges from 0 to 16 and is categorised as inadequate health literacy (< 8 points), problematic (9—12 points), and sufficient (above 13 points)31.

General self-efficacy was assessed using the General self-efficacy scale. It consists of 10 items with a total score ranging from 10 to 4032. Higher scores indicate higher self-efficacy32.

Need of assistance in ADL was assessed using the Barthel Index (BI)33,34. It consists of 10 items related to personal care and mobility with a total score ranging from 0 to 100. Higher scores indicate greater independence34.

Depression symptoms were assessed using the subscale Depression of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. The subscale Depression consists of 7 items. The total score ranges from 0 to 21. Higher scores indicate greater depression symptoms, and a score of ≥ 4 is considered a cut-off for depression symptoms after stroke35.

Perceived impact of stroke on participation was assessed with the Stroke Impact Scale, domain participation. The total score ranges from 0 to 100. Higher scores indicate lower perceived impact36.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe caregivers’ characteristics and caregiver burden. The selected variables were based on a thorough review of the literature concerning factors associated with caregiver burden and aimed to incorporate those considered potentially influential. The explanatory variables of interest include general self-efficacy, need for assistance in ADLs, depression symptoms, and perceived participation. Covariates include the stroke survivor’s age and cohabiting status to help control for demographic variability that could influence the relationship between health literacy and caregiver burden. Due to the sample size, each model was limited to a maximum of five variables to maintain statistical validity and avoid overfitting. Therefore, variables were analyzed across different models, ensuring comprehensive coverage without compromising the clarity of the results. In a first step, univariate ordinal logistic regression was carried out to analyse single variables that were associated with caregiver burden. The variables analysed in the univariate analysis were cohabiting status and stroke survivors’ age, sex, health literacy, general self-efficacy, need of assistance in ADL, depression symptoms, and perceived participation. In a second step, statistical models were built to analyse the association between stroke survivors’ health literacy and caregiver burden:

-

Model A: health literacy, general self-efficacy, cohabiting status, need of assistance in ADL.

-

Model B: health literacy, general self-efficacy, cohabiting status, need of assistance in ADL, depression symptoms.

-

Model C: health literacy, general self-efficacy, cohabiting status, need of assistance in ADL, perceived participation.

-

Model D: health literacy, general self-efficacy, cohabiting status, need of assistance in ADL, stroke survivor’s age.

Caregiver burden was analysed in the regression models as an ordinal variable categorised in low, moderate, and high burden. The variables cohabiting status and sex was analysed as a dichotomous variable. The other variables used in the models were analysed as continuous variables.

Results were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05. All analyses were carried out with R, version 4.2.2.

Results

Among the stroke survivors, median age was 75 and 80% were male. More than a half of the stroke survivors had a university education, and 24% were working. Health literacy was sufficient among 60%. Median general self-efficacy was 31 (IQR = 28—34), and 40% (n = 18) had cognitive impairment. Most of the stroke survivors were independent regarding need of assistance in ADL (78%), and 74% had no symptoms of depression. Further, median age among caregivers was 71 years, and most were cohabiting with the stroke survivors. The majority of the caregivers were satisfied with life as a whole and reported low caregiver burden. Table 1 presents the caregivers’ and stroke survivors’ characteristics.

Stroke survivors’ health literacy was not associated with caregiver burden in the univariate analysis (Table 2). Other variables were found to be associated with lower caregiver burden: higher levels of general self-efficacy and perceived participation, lower levels of depression symptoms, and less need of assistance with ADL.

Stroke survivors’ health literacy was not associated with caregiver burden when controlling for different variables in the regression models (Table 3). After adjustment in the statistical models, need of assistance in ADL remained statistically significant, i.e., less need of assistance in ADL was associated with lower caregiver burden in all models except in Model C (health literacy, general self-efficacy, cohabiting status, need of assistance in ADL, perceived participation). Lower levels of depression symptoms, higher levels of perceived participation and increased age remained statistically significant in the models and were associated with lower caregiver burden.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the relationship between health literacy in stroke survivors and caregiver burden. Health literacy was not found to be associated with caregiver burden when adjusting for cohabiting status and stroke survivors’ age, general self-efficacy, need of assistance in ADL, depression symptoms, and perceived participation in the statistical models. However, less need of assistance in activities of daily living, lower levels of depression symptoms, and higher levels of participation were identified as significant contributors to a low caregiver burden.

Despite controlling for different factors, health literacy was not associated with caregiver burden. One possible explanation could be that stroke survivors’ psychological and physical abilities overshadow the importance of their health literacy. Although previous studies have predominantly focused on caregivers’ health literacy22, the relationship between care recipients’ health literacy and caregiver burden remains poorly understood. As the study sample consisted mostly of stroke survivors with high health literacy and a high level of independence, and caregivers with a low burden, it is conceivable that this association may manifest differently in other stroke-related samples.

Interestingly, despite the majority of caregivers living with the stroke survivor, cohabitation itself was not found to be associated with caregiver burden. The literature presents mixed findings on this topic. For instance, one study reported that higher caregiver burden was associated with not living with the stroke survivor37, while another found that cohabiting with the stroke survivor was associated with higher caregiver burden8. One possible explanation for these contradictory findings could be attributed to differences in the demographic composition of the caregiver population studied. Unlike the present study, where most caregivers were partners, the previous study involved a significant proportion of caregivers who were the children of the stroke survivors37.

Factors such as less need of assistance in ADL, lower levels of depression, higher levels of participation, and older age were consistently associated with lower caregiver burden across the statistical models. Our findings corroborate with a prior study where caregivers of individuals requiring greater assistance reported higher caregiver burden14,15, while post-stroke depression exacerbated caregiver burden11,16. This highlights the importance of developing strategies to support caregivers of stroke survivors with more pronounced disabilities and depression after stroke. The association between older age and caregiver burden should, however, be interpreted with caution. A previous literature review revealed inconsistent findings, suggesting that the relationship between age and caregiver burden may be influenced by other factors such as time spent on caregiving and stroke survivors’ cognitive functioning, which is not accounted for in the present study11.

Higher participation was associated with lower caregiver burden in the present study. An intervention programme for improving participation after acquired brain injury also reported that improved participation was associated with reduced caregiver burden12. This suggests that strategies to increase participation in stroke survivors may also be important to the caregivers as a way to reduce their burden.

Notably, stroke survivors’ general self-efficacy was associated with low caregiver burden only in the univariate analysis, highlighting its potential role in mitigating caregiver burden. Moreover, higher self-efficacy has been shown to be associated with lower depression symptoms and better functioning38,39. Self-efficacy seems to play a role in health decisions40 and has previously been found to be associated with higher health literacy among stroke survivors41. Future studies elucidating the interplay between care recipients’ self-efficacy and caregiver burden, including changes over time, are warranted.

Lastly, the sex of the caregiver was not associated with caregiver burden. Previous research has found no association between sex and caregiver burden among caregivers of persons with Parkinson’s Disease42, while another study found that factors associated with caregiver burden may be gender-specific among caregivers of persons with cancer43. How gender plays a role in caregiver burden in relation to stroke survivors is less studied and should be further explored in larger studies.

Strengths and limitations

This study was based on a secondary analysis of data collected for a longitudinal study investigating care transitions in stroke survivors. Despite the limit sample size, the current study addresses a notable gap in the literature and provides a foundation for future research in the field. Additionally, the identification of other significant factors affecting caregiver burden can be used to tailor interventions targeting caregivers’ health. While the present study brings valuable insights into the association between stroke survivors’ health literacy and caregiver burden, the results must be interpreted with caution due to its exploratory approach and small sample size.

One limitation of this study is the exclusion of cognition impairment from the statistical models, despite evidence that cognitive functioning in individuals with brain injuries is associated with caregiver burden11. This decision was made due to missing data for the variable assessing cognitive impairment and concerns about potential collinearity, which could have comprised the integrity of the models.

Despite the high burden category comprising only 8% of the sample, an ordinal regression was conducted. Assuming that caregiving is a nuanced experience, this method allowed us to preserve detailed information about the distribution of caregiver burden and maintain the original categorization used in the instrument. However, this has implications for the generalizability of the results due to the sample size.

Lastly, another limitation concerns the sample of the study, with a high proportion of significant others experiencing low caregiver burden and patients with mild consequences of a stroke and high health literacy. The composition of the sample may limit generalisability to populations with high caregiver burden and more severe stroke outcomes.

Conclusion

Stroke survivors’ health literacy was not associated with caregiver burden one year post-discharge from hospital. These results must be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size. Future studies with larger samples, focusing on populations with lower functioning after stroke, are recommended to further elucidate this association.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kuriakose, D. & Xiao, Z. Pathophysiology and treatment of stroke: present status and future perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 7609 (2020).

Saini, V., Guada, L. & Yavagal, D. R. Global epidemiology of stroke and access to acute ischemic stroke interventions. Neurology 97, S6–16 (2021).

Winstein, C. J. et al. Guidelines for adult stroke rehabilitation and recovery. Stroke 47, e98–169 (2016).

Kokorelias, K. M. et al. Caregiving is a full-time job impacting stroke caregivers’ health and well-being: a qualitative meta-synthesis. Health Soc. Care Community. 28, 325–340 (2020).

Liu, Z., Heffernan, C. & Tan, J. Caregiver burden: a concept analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 7, 438–445 (2020).

Loh, A. Z., Tan, J. S., Zhang, M. W. & Ho, R. C. The global prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms among caregivers of stroke survivors. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 18, 111–116 (2017).

Rigby, H., Gubitz, G. & Phillips, S. A systematic review of caregiver burden following stroke. Int. J. Stroke. 4, 285–292 (2009).

Pont, W. et al. Caregiver burden after stroke: changes over time? Disabil. Rehabil. 42, 360–367 (2020).

Zhu, W. & Jiang, Y. A meta-analytic study of predictors for informal caregiver burden in patients with stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 27, 3636–3646 (2018).

Andrew, N. E., Kilkenny, M. F., Naylor, R., Purvis, T. & Cadilhac, D. A. The relationship between caregiver impacts and the unmet needs of survivors of stroke. Patient Prefer Adherence. 9, 1065–1073 (2015).

Kjeldgaard, A., Soendergaard, P. L., Wolffbrandt, M. M. & Norup, A. Predictors of caregiver burden in caregivers of individuals with traumatic or non-traumatic brain injury: a scoping review. NeuroRehabilitation 52, 9–28 (2023).

Gerber, G. J. & Gargaro, J. Participation in a social and recreational day programme increases community integration and reduces family burden of persons with acquired brain injury. Brain Inj. 29, 722–729 (2015).

Bosma, M. S., Nijboer, T. C. W., Caljouw, M. A. A. & Achterberg, W. P. Impact of visuospatial neglect post-stroke on daily activities, participation and informal caregiver burden: a systematic review. Ann. Phys. Rehabil Med. 63, 344–358 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Burden of informal care in stroke survivors and its determinants: a prospective observational study in an Asian setting. BMC Public. Health. 21, 1945 (2021).

Kum, C. et al. Theoretically based factors affecting stroke family caregiver health: an integrative review. West. J. Nurs. Res. 44, 338–351 (2022).

Dou, D. M., Huang, L. L., Dou, J., Wang, X. X. & Wang, P. X. Post-stroke depression as a predictor of caregiver burden of acute ischemic stroke patients in China. Psychol. Health Med. 23, 541–547 (2018).

World Health Organization. Ninth global conference on health promotion, Shanghai 2016. (2016). https://www.who.int/teams/health-promotion/enhanced-wellbeing/ninth-global-conference/health-literacy

Sørensen, K. et al. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public. Health. 12, 80 (2012).

Feldman, P. H., McDonald, M. V., Eimicke, J. & Teresi, J. Black/Hispanic disparities in a vulnerable post-stroke home care population. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities. 6, 525–535 (2019).

Hahn, E. A. et al. Health and functional literacy in physical rehabilitation patients. HLRP Health Lit. Res. Pract. 1, e71–85 (2017).

Fleisher, J. E., Shah, K., Fitts, W. & Dahodwala, N. A. Associations and implications of low health literacy in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord Clin. Pract. 3, 250–256 (2016).

Yuen, E. Y. N., Knight, T., Ricciardelli, L. A. & Burney, S. Health literacy of caregivers of adult care recipients: a systematic scoping review. Health Soc. Care Community. 26, e191–206 (2018).

Cianfrocca, C. et al. The effects of a multidisciplinary education course on the burden, health literacy and needs of family caregivers. Appl. Nurs. Res. 44, 100–106 (2018).

Lindblom, S., Tistad, M., Flink, M., Laska, A. C. & von Koch, L. Referral-based transition to subsequent rehabilitation at home after stroke: one-year outcomes and use of healthcare services. BMC Health Serv. Res. 22, 594 (2022).

Lindblom, S., Flink, M., Sjöstrand, C., Laska, A. C. & von Koch, L. Perceived quality of care transitions between hospital and the home in people with stroke. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 21, 1885–1892 (2020).

Fugl-Meyer, A. R., Melin, R. & Fugl-Meyer, K. S. Life satisfaction in 18- to 64-year-old swedes: in relation to gender, age, partner and immigrant status. J. Rehabil Med. 34, 239–246 (2002).

Cheung, F. & Lucas, R. E. Assessing the validity of single-item life satisfaction measures: results from three large samples. Qual. Life Res. 23, 2809–2818 (2014).

Shi, D., Chen, X. & Li, Z. Diagnostic test accuracy of the Montreal cognitive assessment in the detection of post-stroke cognitive impairment under different stages and cutoffs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol. Sci. 39, 705–716 (2018).

Elmståhl, S., Malmberg, B. & Annerstedt, L. Caregiver’s burden of patients 3 years after stroke assessed by a novel caregiver burden scale. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 77, 177–182 (1996).

Bergman, L., Nilsson, U., Dahlberg, K., Jaensson, M. & Wångdahl, J. Validity and reliability of the Swedish versions of the HLS-EU-Q16 and HLS-EU-Q6 questionnaires. BMC Public. Health. 23, 724 (2023).

Wångdahl, J., Lytsy, P., Mårtensson, L. & Westerling, R. Health literacy among refugees in Sweden – a cross-sectional study. BMC Public. Health. 14, 1030 (2014).

Schwarzer, R. The general self-efficacy scale (GSE). Anxiety Stress Coping. 12, 329–345 (2010).

Duffy, L., Gajree, S., Langhorne, P., Stott, D. J. & Quinn, T. J. Reliability (inter-rater agreement) of the Barthel Index for assessment of stroke survivors: systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 44, 462–468 (2013).

Mahoney, F. I. & Barthel, D. W. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md. State Med. J. 14, 61–65 (1965).

Sagen, U. et al. Screening for anxiety and depression after stroke: comparison of the hospital anxiety and Depression Scale and the Montgomery and Asberg Depression Rating Scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 67, 325–332 (2009).

Duncan, P. W. et al. The stroke impact scale version 2.0: evaluation of reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change. Stroke 30, 2131–2140 (1999).

Pucciarelli, G. et al. Quality of life, anxiety, depression and burden among stroke caregivers: a longitudinal, observational multicentre study. J. Adv. Nurs. 74,1875–1887 (2018).

Volz, M., Voelkle, M. C. & Werheid, K. General self-efficacy as a driving factor of post-stroke depression: a longitudinal study. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 29, 1426–1438 (2019).

Jones, F. & Riazi, A. Self-efficacy and self-management after stroke: a systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 33, 797–810 (2011).

Sheeran, P. et al. The impact of changing attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy on health-related intentions and behavior: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 35, 1178–1188 (2016).

Hess Engström, A., Flink, M., Lindblom, S., von Koch, L. & Ytterberg, C. Association between general self-efficacy and health literacy among stroke survivors 1-year post-discharge: a cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 14, 7308 (2024).

Klietz, M. et al. One year trajectory of Caregiver Burden in Parkinson’s disease and analysis of gender-specific aspects. Brain Sci. 26;11, 295 (2021).

Schrank, B. et al. Gender differences in caregiver burden and its determinants in family members of terminally ill cancer patients. Psychooncology 25, 808–814 (2016).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute.

This is study was funded by the Doctoral School in Healthcare Sciences, Karolinska Institutet [2–134/2016], Neuro Sweden, and the Swedish Stroke Association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AHE: Conceptualisation (supporting), data curation, methodology (supporting), formal analysis (lead), visualisation, writing original draft (lead), writing – review and editing (equal); SL: Data curation, investigation, writing – review and editing (equal); MF: Conceptualisation (supporting), methodology (supporting), writing – review and editing (equal); SS: formal analysis (supporting), writing original draft (supporting), writing – review and editing (equal); LenavK: Methodology (supporting), writing – review and editing (equal); CY: Conceptualisation (lead), methodology (lead), project administration, funding acquisition, supervision, writing – review and editing (equal).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hess Engström, A., Lindblom, S., Flink, M. et al. Stroke survivors’ health literacy is not associated with caregiver burden: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 4720 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89523-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89523-x