Abstract

This paper investigates the complex interaction between wave hydrodynamics and aquatic vegetation, emphasizing its importance for the management of coastal ecosystems. Vegetation plays a crucial role in the dynamics of river and coastal flows, influencing their structure and turbulence, as well as the transport and distribution of nutrients, sediments, ecosystems, and habitats. For example, mangroves serve as a natural defense against tsunamis and extreme waves. Nature-based coastal defense technologies are increasingly being adopted, in alignment with the principles of ecohydraulics. Riparian vegetation represents one of the most effective nature-based solutions for coastal protection. In addition, lagoons and estuarine areas often feature structures such as mussel farms and boat guides, such as the Venetian Briccole. Therefore, accurate evaluation of wave transmission through cylindrical stem arrays is essential to assess their coastal protection capabilities and designing effective protective structures, such as mangrove restoration projects. This paper presents a theoretical study of wave attenuation for regular (Airy) and solitary waves propagating through rigid, emergent, and submerged cylindrical stems on horizontal and sloping bottoms. The theoretical model results are compared with numerical simulations obtained using the SPH (Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics) Lagrangian numerical code, which does not rely on mesh-based methods. Furthermore, the bulk drag coefficients of rigid stem arrays are evaluated on the basis of stem density, diameter, and submersion ratio. This paper aims to engage a broad audience, including scientists and practitioners in ecohydrology, coastal hydrodynamics, and environmental management, providing actionable insights to improve the ecological resilience of coastal systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The paper explores both theoretical and numerical analyses to examine how Airy and solitary waves interact with rigid emergent or submerged stem arrays resembling rigid vegetation or poles, which are present for diverse purposes such as mussel farming, ocean-based wind farms, or navigational systems. Vegetation is critically known to significantly influence the transport and diffusion processes of nutrients and sediments and impact ecosystems and habitats, helping to conserve and restore the coastal environment by controlling the displacement and transport of sediments1,2,3. It also helps to dissipate the wave energy4 and current wave flows5. According to6, marshes and mangroves decrease coastal erosion by alleviating waves and storm surges, and riparian vegetation contributes to bank stabilization. Mangroves serve as shields against coastal erosion and disasters, such as tsunamis. In addition, they mitigate climate change by storing large amounts of carbon within their biomass and substrates, making them among the most carbon-rich tropical forests globally. In the aftermath of devastating tsunami events, numerous studies7,8,9,10,11,12 have emphasized the protective role of mangrove forests along coastlines. In fact, mangroves can protect coastlines from wind and tidal wave actions8. However, specific research indicates that tsunamis and storm surges respond differently. As severe tsunami and surge water levels increase, the attenuation of mangrove forests may decrease. The duration of tsunami waves can also affect mangrove mitigation, as plants can be damaged or depleted as the wave traverses the coastal forest. A study after the 26 December 2004 tsunami along the southeast coast of India underscores the importance of coastal mangrove ecosystems and settlement locations to protect lives and assets from tsunamis. Human casualties and damage diminished with increasing coverage of coastal vegetation and the distance and elevation of human settlements from the sea. Human habitation is advised to remain more than 1 km inland from shorelines in elevated zones behind dense mangroves or other coastal vegetation. Specific plant species suitable for growing between human settlements and the sea for coastal protection have been recommended. Wetlands act as barriers against erosion and damage by reducing the impact of waves. Despite this vital role, understanding wetland wave damping remains incomplete, and reliable engineering methods to determine vegetation-induced wave damping are currently unavailable.

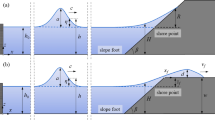

The interaction between waves and structures is similar due to poles from mussel farms and offshore wind farms, among other scenarios13,14. Figure 1 illustrates a schematic representation of a mangrove forest, modeled as rigid obstacles that interact with waves. Of particular interest is the interaction between coastal vegetation, represented as an array of rigid cylinders, and both Airy waves and solitary waves. Moreover, an input parameter required by the theoretical model is the bulk drag coefficient of the stem array. These values were carefully selected for all the analyzed configurations to ensure that the wave damping results of the theoretical model were in excellent agreement with the numerical ones. This approach enabled the evaluation of the bulk drag coefficient, which was subsequently compared with certain theoretical laws available in the literature. The results either confirmed the validity of these laws or allowed their applicability to be extended to regions not previously analyzed in the literature.

The structure of this paper is as follows. Initially, a theoretical model for the attenuation of Airy and solitary waves is presented, allowing for a preliminary evaluation of wave height reduction resulting from energy dissipation by an array of cylindrical obstacles, which may be either emergent or submerged, on either flat or sloped beds. The results of the theoretical and numerical models were calibrated against data available in the literature. Subsequently, a comparison was performed between the theoretical model predictions and numerical simulations conducted using the SPH (Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics) meshless Lagrangian method. This comparison validated the applicability of the theoretical models to the scenarios under investigation. In addition, the study analyzed the bulk drag coefficient of rigid stem arrays, taking into account parameters such as distance, diameter of individual stems, and degree of submergence.

Formulation of the problem

The effect of obstructions is considered using the bulk drag coefficient \(C_D\) in drag terms. In the following, waves propagating in an ambient flow with a regular square array of emergent or submerged cylinders of uniform diameter d and distance s will be considered. Other key parameters of the cylinder array used in the present paper are the frontal area per unit volume of obstructions, \(a=nd\), which is equal to \(d/s^2\) in the case of a periodic square array, where n is the number of elements per unit of planar area, and the solid volume fraction of the stem \(\phi =n\pi d^2/4\). Figure 2 shows the definition of key geometric parameters for an array of cylinders of uniform diameter d and center-to-center distance s.

As shown by15, various resistance laws of drag can be derived for flow in porous media. In particular, in free surface or atmospheric obstructed flow16, the following quadratic form can be assumed

Local variations of velocity profiles detected in obstacles-affected flows are not considered here. In other terms, as proposed by17 in the theoretical model, the average velocity values in space are considered rather than the individual point values, which can even be null on the walls of the stems affected by the flow (see also18). Therefore, the enveloped cross section velocity profile is taken into account to evaluate the effects of the presence of obstacles on the entire velocity profile, without considering the local variations upstream and downstream of the cylinders. The reflection effects of the wave with respect to each row of cylinders will not be considered, a situation that the literature shows is of certain importance mainly at the beginning of the stem array. Therefore, wave dissipation evaluations will be performed starting from the wave height value starting right from the first row of cylinders. As shown by19, previous studies have highlighted that the variability of the bulk drag coefficient depends also to the processes of sheltering, which takes place when the stem rows downstream are exposed to the wake of the upstream stem rows, resulting in a lower drag force. Sheltering under waves depends on the wave length, which in the case of the present paper is surely greater than the stem distance. Therefore, in this paper, the sheltering effect depends only on the ratio of the distance and diameter of the stem19.

That being said, the wave-averaged work takes the following form

Methods

Problem formulation for the damping of Airy waves

As shown by20, the equation describing the free surface as a function of time t and horizontal distance x for an Airy wave is

where H is the wave height, T the wave period, and the wave length is

with h the mean depth of the water, and the celerity of the wave is

The group celerity is

where, as is well known, the dimensionless quantity G is approximately equal to unity in shallow water and tends to zero in deep water, and the energy per unit of surface area is

The energy dissipated due to the drag forces acting on the obstacle array is obtained as follows

The horizontal wave orbital velocity component is

where

is the wave number and

The force per unit volume F in the stem array is

where \(F_D\) is the drag force per unit volume and \(F_M\) the inertial contribution, which is proportional to the partial time derivative of u19, that is,

Therefore, the work performed by \(F_M\) per wave period is equal to zero. It should be noted that, in the case analyzed above, the velocity u does not depend on the time variable t. Therefore, the work performed by \(F_D\) over a wave cycle is

where \(\alpha\) is a coefficient whose value is between the limits of 1, when the stem has zero height, and 0 when the stem develops for the whole height h. Since the Airy waves are of small amplitude, in the latter case it is observed that the integral, which should extend up to \(z=\eta\), stops up to \(z=0\). In addition to the constant term \(\frac{1}{2} \rho C_D a\), Eq. (14) becomes

Problem formulation for the damping of solitary waves

As is well known, a solitary wave is a self-reinforcing localized wave that maintains its shape while propagating at a constant velocity. Solitary waves are caused by cancelation of non-linear and dispersive effects in the medium. The soliton phenomenon was first described by21. In nature, it is difficult to form a truly solitary wave because, at the trailing edge of the wave, there are usually small dispersive waves. However, long waves, such as tsunamis and waves resulting from large displacements of water due to landslides or earthquakes, behave approximately as solitary waves.

The elevation of the free surface of a solitary wave22 is given by:

where X is the horizontal axis, with its origin at the wave crest, t is time, h is the depth of the water and H is the amplitude related to the velocity, C, as follows (see also23)

The total energy for a solitary wave is about evenly divided between kinetic and potential energy. The total energy per unit width of the crest between \(-X/h\) and X/h is equal to

and the total energy per unit crest width, between \(-\infty\) and \(+\infty\), is

As shown by24, in the case of \(H/h=0.5\), 98% of the energy is contained between \(X/h=\pm 2.1\) and, generally, a value of energy greater than 90% is contained between \(X/h=\pm 2.5\). Therefore, defining a width, \(L_{90}\), which contains more than 90% of the energy per unit of crest width, as

then, the energy per unit area is

The study relates to the propagation of solitary waves in nearshore areas where mangroves or other rigid vegetation are present. Consequently, the water depth is relatively shallow, resulting in the group celerity coinciding with the wave celerity. Given this assumption, the energy dissipated due to the drag forces acting on the obstacle array is obtained as follows

where \(\epsilon _\nu\) is the wave-averaged work. Equation (22) can be written as follows

References25 and24 observed that the horizontal orbital velocity for a solitary wave is

where z is the distance from the bottom, and M and N are functions of H/h, defined by the following equations

The Taylor series expansion of Eq. (24) at \(z=0\) is given by

with

The Taylor series expansion of Eq. (24) at \(z=z_0\) arrested at the second order is given by

Generalizing, in the case of a Taylor series expansion at \(z=z_0\) truncated at order \(m-1\), the remaining terms are of the following order of magnitude

and, therefore, the convergence condition is as follows

In conclusion, integral 2 is

where

Equations (28) and (31) enable us to calculate the wave-averaged work.

SPH numerical solution

SPH (Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics) is a meshless, Lagrangian method where the fluid domain is represented by nodal points that are scattered in space with no grid structure and move with the fluid. For the sake of brevity, the full general description of the method is not reported, and it is possible to refer to specialized books26,27. It has proven to be applicable to a wide variety of flows, including wave breaking28,29,30, hydraulic jumps31,32, interaction between jets and waves33,34,35, and multiphase flows36. In the present paper, a WCSPH model coupled with a subparticle scale (SPS) approach to modeling turbulence37 has been used. The specific features of the SPH method here used are detailed in33. The motion is represented by the Navier-Stokes equations for a weakly compressible fluid. In a Lagrangian frame, the equations of continuity and momentum take the following form

where \(\rho\) is the density, \({\varvec{v}}\) is the velocity vector, P is the pressure, \(D_i\) represents a numerical diffusive term, \(\Gamma\) denotes the dissipation terms and \({\varvec{g}}\) is the gravity acceleration vector. The summations in (33) are extended to all particles j located within the circular domain, centered on i and of radius \(2h_{SL}\) (with \(h_{SL}\) as the smoothing length), where the kernel function \(W_{ij}\) is defined. Here, the adopted kernel function \(W_{ij}\) is the cubic-spline kernel function38. In order to reduce the density fluctuation, the following numerical diffusive term \(D_i\)39 is introduced

where \(\delta\) is the Delta-SPH coefficient, which controls the magnitude of the diffusion term, \(c_i\) is the numerical speed of sound, \(V_j\) is the associated volume of the j-th particle and \(\psi _{ij}\) is the artificial dissipation term. Here, the artificial dissipation term proposed by40 was chosen. The momentum dissipation term \(\Gamma\) is obtained by coupling the viscous dissipation in the laminar regime, as approximated by41, with a subparticle scale model (SPS)42. The parameter \(\delta\) was set equal to 0.1 while the time step dt was imposed with values \(dt \le 0.0003\). A more detailed description of the LES-SPS model using Favre averaging43 in a weakly compressible approach can be found in28. The SPH results discussed here were obtained using the hardware-accelerated dual-SPHysics code44. Since its first release in 2011, DualSPHysics has been shown to be robust and accurate for simulating free surface flows, but requires high computational cost. Therefore, recently, the high-performance computing of SPH has focused mainly on Graphical Processing Units (GPUs)45, which are superior in terms of price and energy consumption compared to traditional CPUs. In DualSPHysics, the C++ programming language is used to code the SPH formulation for CPU execution, while GPU executions are based on the NVIDIA CUDA architecture46. The three-dimensional flow was simulated by discretizing the computational domain through a particle distribution with initial particle distance \(D_x=D_y=D_z\) (Fig. 3). Starting from the wave paddle, the numerical tank has a flat bottom that extends 10 m,while the remaining bottom has a slope of 1/20. A vegetation canopy of length \(l_v=3\) m is housed 4 m from the channel inlet \(l_0\).

Calibration and results of the theoretical wave damping models and the numerical model

In the following, each theoretical model will first be validated using data from the literature. Furthermore, the results of the theoretical model for wave damping will be presented for both Airy waves and solitary waves. The aim is to demonstrate how wave damping is strongly influenced by the presence of vegetation, which therefore represents a nature-based solution for coastal protection against extreme storm surges and freak waves. The calibration of the numerical model was performed using data from laboratory experiments previously conducted by one of the authors. Subsequently, a comparison was carried out between the results of the theoretical wave damping models proposed in this paper and those obtained from numerical simulations. This comparison aims to verify the convergence of the two approaches and to evaluate the bulk drag coefficient of the stem array. The diagrams of the results of the theoretical model are designed to highlight the differences in wave damping behavior between Airy waves and solitary waves prior to their breaking, beyond which the theoretical equations for either type of wave can no longer be applied.

Damping of airy waves

Refer to the paragraph “Problem formulation for the damping of Airy waves” for the description of the theoretical model used.

In the following, in a strategic way, waves with higher steepness compared to strictly Airy waves will also be analyzed, although not significantly different from Airy waves. The logic is to capture the damping effects more effectively on wave heights induced by rigid vegetation. It is important to note that in the presence of a sloped bottom, the wave steepness will naturally increase, even if the initial wave is a perfect Airy wave without the second harmonic. Therefore, the objective is to reconcile these two aspects: the analyzed wave can be treated as an Airy wave where the second harmonic is negligible, allowing the use of Airy theory as a first-order approximation, while ensuring sufficiently high wave amplitudes to accentuate the damping effects.

The theoretical model was validated using the Airy wave configuration described by47. Specifically, the configuration features emergent, rigid vegetation with a wave height of 0.08 m, a water depth of 0.4 m, a period of 1.8 s, a stem diameter of 0.02 m, a stem spacing of 0.67 m, and a zero-slope channel. For more details on the experimental setup, please refer to Wang. Figure 4 shows the comparison between the experimental data of the configuration of the cited literature47 and the proposed theoretical model. The x-axis of the figure represents the horizontal direction in the wave propagation path, starting from the beginning of the vegetated zone. The \(x\)-axis of the figure represents the horizontal direction along the wave propagation path, starting from the beginning of the vegetated zone. The values of the \(x\) axis have been dimensionlessed using both the depth of the water in the wave channel (\(h_s\)) and the depth of the water wavelength (\(L_0\)). Therefore, two \(x\)-axes are presented. In the theoretical model, a bulk drag coefficient \(C_D = 4.5\) was used, which aligns with the values suggested by47. Taking into account typical experimental uncertainties, the comparison validates the theoretical model.

Figure 5 illustrate a theoretical example of Airy wave heights as they propagate over obstacles of diameter d of 0.1 m, on either a flat (see Fig. 5a) or sloped (see Fig. 5b) bottom. For the previously noted simulations, it was assumed that the wave period is T is 10 s and that at the start of the obstacle section, denoted by \(x = 0\), the wave height \(H_s\) is 2 m, with an initial depth \(h_s\) of 10 m, which remains unchanged and equals h for a flat bottom. Other parameters, including the submersion ratio of the obstacles, were varied as detailed in the legend of the referenced figures. In paragraph 3, the mathematical developments leading to the final formulation of the theoretical model for wave damping are presented, both for Airy waves and solitary waves.

Damping of solitary waves

Refer to “Problem formulation for the damping of solitary waves” for the description of the theoretical model used.

The theoretical model was validated using the solitary wave configuration described by48. Specifically, the configuration features emergent, rigid vegetation with a wave height of 0.04 m, a water depth of 0.15 m, a stem diameter of 0.01 m, a stem spacing of 0.0425 m and a zero-slope channel. For more details on the experimental setup, please refer to Wang. Figure 6 shows the comparison between the experimental data of the Wang configuration and the proposed theoretical model. The values of the \(x\) axis have been dimensionlessed using both the depth of the water in the wave channel (\(h_s\)) and the depth of the water wavelength (\(L_{90}\)).

The theoretical model was validated using the solitary wave configuration described by48. Specifically, the configuration features emergent, rigid vegetation with a wave height of 0.037 m, a water depth of 0.15 m, a stem diameter of 0.01 m, a stem spacing of 0.0425 m, and a zero slope channel. For more details on the experimental setup, please refer to48. Figure 6 shows the comparison between the experimental data obtained from48and the proposed theoretical model. The \(x\)-axis in the figure represents the horizontal direction along the wave propagation path, starting from the beginning of the vegetated zone. To facilitate analysis, the values of the \(x\) axis have been dimensionlessed using two parameters: the depth of the water in the wave channel (\(h_s\)) and the wavelength (\(L_{90}\)). In the theoretical model, a bulk drag coefficient \(C_D = 1.0\) was used, which aligns with the values suggested by47. Taking into account typical experimental uncertainties, the comparison validates the theoretical model.

Figure 7 illustrate an example of the theoretical wave heights of solitary waves traveling over obstacles on a flat (Fig. 7a) or a sloped (Fig. 7b) seabed. For the simulations discussed, a wave height \(H_s\)=2 m was used at the beginning of the obstacle section, at \(x = 0\), with an initial depth of water \(h_s\) = 10 m, which remains unchanged and equals h for a flat bottom. The figures also include a second horizontal axis showing the variation of x dimensionlessed with the wave length \(L_{90}\) (or \(L_{90s}\), which is the same as \(L_{90}\) at the beginning of the vegetated area.) Various other parameters were adjusted, including the submersion ratio of the obstacles, as detailed in the figures’ legends.

SPH numerical solution

Calibration of the numerical model

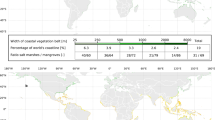

The first numerical simulations have been run for the Airy wave with the characteristics shown in Table 1.

Table 1 refers to an Airy wave that was experimentally studied by49 in the absence of vegetation. The calibration of the SPH numerical code was conducted based on this wave, using its elevation profiles in a section located 20.24 m from the numerical wave paddle. As mentioned previously, the experimental values of wave elevation are available in49, to which the reader is referred for further information and details about the experimental setup. In particular, maintaining a constant ratio between the smoothing length and the initial particle distance (\(h_{SL}/D_x\)= 2), an investigation was carried out on the impact of the initial particle distance on the quality of the numerical results. The three-dimensional flow was simulated by discretizing the computational domain using a relative particle distance of \(D_x\) = 0.01 m and 0.005 m. It is evident that the simulation at the lowest resolution (\(D_x\) = 0.01 m) fails to accurately predict the wave crest. However, as demonstrated by30, the accuracy of the SPH method is influenced not only by the initial particle distance \(D_x\) but also by the ratio between the smoothing length and the initial particle distance \(h_{SL}/D_x\). Thus, the effect of \(h_{SL}/D_x\) has been examined. Runs with \(D_x\) = 0.01 m and 0.005 m, respectively, were carried out, increasing \(h_{SL}/D_x\) from 2 to 2.5. The results show that the best results are achieved using the ratio \(h_{SL}/D_x\) = 2.5, especially evident in the case of a relative particle distance of \(D_x\)= 0.01 m, where the solution closely resembles that obtained with \(D_x\) = 0.005 m. However, considering the diameter of the stem (equal to 0.02 m) and the width of the flume (0.08 m), all simulations were carried out using the highest resolution of \(D_x\) = 0.005 m with a particle count of \(N_p\) = 15,634,080 representing a high level of refinement, that is, 4 particles per stem and about 6 particles between the stem and the boundary. For the sake of brevity, only the effect of the ratio between the smoothing length and the initial particle distance \(h_{SL}/D_x\) on the numerical simulation will be shown (Fig. 8).

A second set of simulations refers to solitary waves, the characteristics of which are reported in Table 2.

The validity of the adopted numerical scheme was tested against the solution for a solitary wave elevation, as described by Eq. (16) (see22,24). In all simulations, the ratio between the smoothing length and the initial particle spacing (\(h_{SL}/D_x = 2.5\)) was kept constant. The three-dimensional flow was simulated by discretizing the computational domain with relative particle spacings of \(H/D_x = 20\), 40, 80, and 100, respectively. For the sake of brevity, only the results of test T2A are presented here (see Fig. 9).

Comparison between theoretical and numerical results of wave damping

Figure 10a,b present a comparison between the numerical results and the theoretical predictions for two configurations of Airy waves, whose characteristics are detailed in Table 1. Specifically, the figures illustrate a comparison of wave height data, normalized with the wave height at the beginning of the cylinder array, as a function of the longitudinal distance, dimensionlessed with the water depth, and as a function of the same longitudinal distance dimensionlessed with the wavelength in deep water.

Figures 11, 12 and 13 also show the corresponding comparison for solitary waves, as described above, with their characteristics provided in Table 2. In this case, the values of \(x\) are dimensionlessed using both \(L_{90}\) and the depth of the water.

The comparison between the data obtained from the numerical code and those from the theoretical models, both properly calibrated with experimental data, demonstrated that both methods yield consistent results and can be effectively employed for the study of wave damping, both for Airy waves and solitary waves.

Bulk drag coefficients

The research work19 established that the bulk drag coefficient is affected by the Keulegan and Carpenter number50, which represents the ratio between drag and inertia forces. This number is calculated as the ratio of the horizontal orbital excursion of water particle motion in the presence of waves to the diameter of the stem. The relationship between \(C_D\) and the Keulegan-Carpenter number in the context of gravity waves was also noted by47. Comparing the data of the bulk drag coefficient from our research with those of47 offers intriguing information. In their research,47 performed experiments with a 10-meter-long model simulating a mature Rhizophora forest, with the aim of exploring hydrodynamic properties and gravity wave attenuation. They introduced an innovative parameter, a modified Keulegan and Carpenter number \(KC_{r_v}=u_pT/r_v\), where \(u_p=u(1-\phi )\) represents the spatially averaged flow velocity in the gaps between the stems, u is the flow velocity, \(r_v=\frac{\pi }{4}\frac{1-\phi }{\phi }d\) is a hydraulic radius associated with obstacles, and T is the wave period. This parameter indicates the spatially averaged flow velocity between the stems. Ultimately, the authors developed a correlation between the bulk drag coefficient and \(KC_{r_v}\), resulting in an empirical expression for \(C_D\). They noticed that this formula offers a highly accurate correlation of drag coefficient properties related to obstacles. It is important to note that the waves investigated in the present study include both Airy waves and solitary waves. In particular, the latter diverge from those examined by47. Consequently, comparisons of the drag coefficient values in the present study were conducted to explore the possibility of expanding the analysis of47. For the configurations that involve solitary waves in this study, the calculation of \(KC_{r_v}\) was performed as described below. Based on Munk’s theory of solitary waves24, the wave period T was derived from both the wavelength and the celerity of waves in shallow water. The numerical configurations provided the velocity values u on the crest of the soliton, allowing the determination of \(u_p=u(1-\phi )\) using a numerical SPH code. In particular, the velocity scale u in these numerical configurations is approximately \(O(1.5\,{\hbox {ms}^{-1}})\), while for Airy wave configurations it is around \(O({0.005}\,{\hbox {ms}^{-1}})\). Figure 14 illustrates that the values \(C_D\) proposed in this study align very well, even with the theoretical framework proposed by47, whose fitted curve has the following equation

Relationship between the \(KC_{r_v}\) number and the \(C_D\) data of three vegetation models of47, with their theoretical curve, their proposal of 95% prediction band and the data of the present study.

Therefore, this study extends the understanding of the trend of the bulk drag coefficient observed by47, as it applies to solitary waves. Moreover, the magnitude of \(C_D\) is consistent with the results reported in15 for solitary waves. This is because solitary waves are categorized as long waves, which are distinguished by flows that, though induced by waves, are most similar to steady currents.

Conclusions

This paper presents two theoretical models for wave damping of regular and solitary waves by cylindrical structures, representing rigid vegetation, submerged or emerging. This topic is of significant importance in the context of nature-based solutions for coastal protection against extreme storm surges and rogue waves. The analyzed configurations focus on scenarios where the spacing between stems is small relative to the wavelength, causing the wake downstream of each stem to interact with subsequent stems before fully developing. Consequently, these configurations exhibit a pronounced sheltering effect, characterized by a low \(s/d\) ratio19. The performance of the theoretical models was validated through numerical simulations conducted with the DualSPHysics code, examining various wave dynamics and cylindrical array configurations. The results confirmed the models’ ability to accurately predict wave damping. Furthermore, an evaluation of bulk drag coefficients (\(C_D\)) for regular and solitary waves supported the validity of the equation proposed by47 and extended its applicability to wave conditions markedly different from Airy waves, such as solitary waves.

Data availability

Data are available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Albayrak, I., Nikora, V., Miler, O. & O’Hare, M. Flow-plant interactions at a leaf scale: effects of leaf shape, serration, roughness and flexural rigidity. Aquat. Sci. 74, 267–286 (2012).

Mossa, M. & De Serio, F. Rethinking the process of detrainment: Jets in obstructed natural flows. Sci. Rep. 6, 39103 (2016).

Mossa, M., Ben Meftah, M., De Serio, F. & Nepf, H. M. How vegetation in flows modifies the turbulent mixing and spreading of jets. Sci. Rep. 7, 6587 (2017).

Mendez, F. J. & Losada, I. J. An empirical model to estimate the propagation of random breaking and nonbreaking waves over vegetation fields. Coast. Eng. 51, 103–118 (2004).

Hu, Z., Suzuki, T., Zitman, T., Uittewaal, W. & Stive, M. Laboratory study on wave dissipation by vegetation in combined current-wave flow. Coast. Eng. 88, 131–142 (2014).

Kathiresan, K. & Rajendran, N. Coastal mangrove forests mitigated tsunami. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 65, 601–606 (2005).

Dahdouh-Guebas, F. & Koedam, N. Coastal vegetation and the asian tsunami. Science 311, 37–38 (2006).

Mazda, Y., Magi, M., Kogo, M. & Hong, P. N. Mangroves as a coastal protection from waves in the tong king delta, vietnam. Mangrove Salt Marshes 1, 127–135 (1997).

Danielsen, F. et al. The asian tsunami: a protective role for coastal vegetation. Science 310, 643–643 (2005).

Das, S. & Vincent, J. R. Mangroves protected villages and reduced death toll during indian super cyclone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 7357–7360 (2009).

Marois, D. E. & Mitsch, W. J. Coastal protection from tsunamis and cyclones provided by mangrove wetlands-a review. Int. J. Biodiversity Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 11, 71–83 (2015).

Mazda, Y., Magi, M., Ikeda, Y., Kurokawa, T. & Asano, T. Wave reduction in a mangrove forest dominated by sonneratia sp. Wetlands Ecol. Manage. 14, 365–378 (2006).

Augustin, L. N., Irish, J. L. & Lynett, P. Laboratory and numerical studies of wave damping by emergent and near-emergent wetland vegetation. Coast. Eng. 56, 332–340 (2009).

Mossa, M. et al. Quasi-geostrophic jet-like flow with obstructions. J. Fluid Mech. 921, A12 (2021).

Nepf, H. M. Drag, turbulence, and diffusion in flow through emergent vegetation. Water Resour. Res. 35, 479–489 (1999).

White, B. L. & Nepf, H. M. Shear instability and coherent structures in shallow flow adjacent to a porous layer. J. Fluid Mech. 593, 1–32 (2007).

Tanino, Y. & Nepf, H. M. Lateral dispersion in random cylinder arrays at high reynolds number. J. Fluid Mech. 600, 339–371 (2008).

Ben Meftah, M. & Mossa, M. A modified log-law of flow velocity distribution in partly obstructed open channels. Environ. Fluid Mech. 16, 453–479 (2016).

Mancheño, A. G. et al. Wave transmission and drag coefficients through dense cylinder arrays: Implications for designing structures for mangrove restoration. Ecol. Eng. 165, 106231 (2021).

Svendsen, I. A., Svendsen, I. A. & Jonsson, I. G. Hydrodynamics of coastal regions (Technical University of Denmark, Den Private ingeniørfond, 1976).

Russell, J. S. Report on waves. In Report of the fourteenth meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, vol. 25 (1844).

Boussinesq, J. Théorie des ondes et des remous qui se propagent le long d’un canal rectangulaire horizontal, en communiquant au liquide contenu dans ce canal des vitesses sensiblement pareilles de la surface au fond. Journal de mathématiques pures et appliquées 17, 55–108 (1872).

Daily, J. W. & Stephan, S. C. Jr. Characteristics of the solitary wave. Trans. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng. 118, 575–587 (1953).

Munk, W. H. The solitary wave theory and its application to surf problems. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 51, 376–424 (1949).

McCowan, J. Vii. on the solitary wave. Lond. Edinburgh Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 32, 45–58 (1891).

Lin, P. & Liu, P.L.-F. Turbulence transport, vorticity dynamics, and solute mixing under plunging breaking waves in surf zone. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 103, 15677–15694 (1998).

Violeau, D. Fluid mechanics and the SPH method: theory and applications (Oxford University Press, 2012).

Dalrymple, R. A. & Rogers, B. D. Numerical modeling of water waves with the sph method. Coast. Eng. 53, 141–147 (2006).

Makris, C. V., Memos, C. D. & Krestenitis, Y. N. Numerical modeling of surf zone dynamics under weakly plunging breakers with sph method. Ocean Model. 98, 12–35 (2016).

De Padova, D., Dalrymple, R. A. & Mossa, M. Analysis of the artificial viscosity in the smoothed particle hydrodynamics modelling of regular waves. J. Hydraul. Res. 52, 836–848 (2014).

De Padova, D., Mossa, M., Sibilla, S. & Torti, E. 3d sph modelling of hydraulic jump in a very large channel. J. Hydraul. Res. 51, 158–173 (2013).

De Padova, D., Mossa, M. & Sibilla, S. Sph numerical investigation of the characteristics of an oscillating hydraulic jump at an abrupt drop. J. Hydrodyn. 30, 106–113 (2018).

Barile, S., De Padova, D., Mossa, M. & Sibilla, S. Theoretical analysis and numerical simulations of turbulent jets in a wave environment. Phys. Fluids 32 (2020).

De Padova, D., Mossa, M. & Sibilla, S. Numerical investigation of the behaviour of jets in a wave environment. J. Hydraul. Res. 58, 618–627 (2020).

De Padova, D., Mossa, M. & Sibilla, S. Characteristics of nonbuoyant jets in a wave environment investigated numerically by sph. Environ. Fluid Mech. 20, 189–202 (2020).

De Padova, D., Meftah, M. B., Mossa, M. & Sibilla, S. A multi-phase sph simulation of hydraulic jump oscillations and local scouring processes downstream of bed sills. Adv. Water Resour. 159, 104097 (2022).

Gotoh, H. Sub-particle-scale turbulence model for the mps method-lagrangian flow model for hydraulic engineering. Comp. Fluid Dyn. J. 9, 339–347 (2001).

Monaghan, J. J. & Lattanzio, J. C. A refined particle method for astrophysical problems. Astron. Astrophys. 149, 135–143 (1985).

Antuono, M., Colagrossi, A. & Marrone, S. Numerical diffusive terms in weakly-compressible sph schemes. Comput. Phys. Commun. 183, 2570–2580 (2012).

Molteni, D. & Colagrossi, A. A simple procedure to improve the pressure evaluation in hydrodynamic context using the sph. Comput. Phys. Commun. 180, 861–872 (2009).

Shao, S. & Lo, E. Y. Incompressible sph method for simulating newtonian and non-newtonian flows with a free surface. Adv. Water Resour. 26, 787–800 (2003).

Fulk, D. A. & Quinn, D. W. An analysis of 1-d smoothed particle hydrodynamics kernels. J. Comput. Phys. 126, 165–180 (1996).

Favre, A. Problems of hydrodynamics and continuum mechanics. Soc. Indust. 231–266 (1969).

Domínguez, J. M., Crespo, A. J. & Gómez-Gesteira, M. Optimization strategies for cpu and gpu implementations of a smoothed particle hydrodynamics method. Comput. Phys. Commun. 184, 617–627 (2013).

Crespo, A. J. et al. Dualsphysics: Open-source parallel cfd solver based on smoothed particle hydrodynamics (sph). Comput. Phys. Commun. 187, 204–216 (2015).

Domínguez, J. M. et al. Dualsphysics: from fluid dynamics to multiphysics problems. Comput. Part. Mech. 9, 867–895 (2022).

Wang, Y., Yin, Z. & Liu, Y. Experimental investigation of wave attenuation and bulk drag coefficient in mangrove forest with complex root morphology. Appl. Ocean Res. 118, 102974 (2022).

Huang, Z., Yao, Y., Sim, S. Y. & Yao, Y. Interaction of solitary waves with emergent, rigid vegetation. Ocean Eng. 38, 1080–1088 (2011).

De Serio, F. & Mossa, M. Experimental study on the hydrodynamics of regular breaking waves. Coast. Eng. 53, 99–113 (2006).

Keulegan, G. H. Forces on sylinder and plates in an oscillating fluid. J. Res. Nat. Bur. Stand. 60, 423–440 (1958).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MM developed the theoretical model and proposed the methodology and conceptualization. DDP conducted the numerical simulations. MM and DDP wrote, reviewed, and edited the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mossa, M., De Padova, D. Interaction between waves and vegetation. Sci Rep 15, 6157 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89627-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89627-4