Abstract

The theoretical energy density of Li-O2 batteries is more than an order of magnitude larger than the current generation of Li-ion batteries. However, their practical performance is far less, in part due to their low true capacities, that is, capacity including the mass of the typically porous active material, electrolyte in the pores and the Li2O2 discharge product. This is further limited by the particulate nature of the product, yielding a theoretical maximum packing density of 74%, impacting both gravimetric and volumetric capacities. Here we introduce carbon nanochains (CNCs), a material synthesized from biomass that is structurally similar to a commonly studied cathode material, multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs). CNCs form densely packed agglomerates with mesoporosity that is similar to that of MWCNTs but far less microporosity, resulting in nearly twice the volumetric capacity and significantly larger true capacity despite obtaining essentially identical gravimetric capacity. Finally, while the initial discharge product is found to be toroidal Li2O2 particles typical of Li-O2 cathodes, it proceeds with the formation of thick films covering the surface of the cathode. This is, to our knowledge, the first report of thick film formation in Li-O2 cells, overcoming the 74% density limit of particulate formation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lithium-oxygen batteries (Li-O2) are a promising battery chemistry with superior theoretical energy densities (~ 3500 Wh/kg) making their development highly desirable1,2,3,4,5. The Li2O2 storage mechanism in Li-O2 cells is strongly correlated to solvent donor number6. Low donor number (LDN) solvents poorly solvate the intermediate superoxide anion (O2−), resulting in surface bound LiO2 intermediate, nucleation and the conformal coating of the cathode material. However, the films only grow to ~ 5 to 10 nm thick prior to passivation. Thus, the capacity of cells using LDN solvents are dependent on the cathode’s available surface area, and given the practical necessity of using materials that maintain structural integrity and have high electronic conductivity, have low gravimetric and volumetric capacities. Alternatively, high donor number (HDN) solvents solubilize superoxide, resulting primarily, but not exclusively, in nucleation in and the precipitation of Li2O2 as toroidal particles from solution. Thus, solution nucleation allows the formation and deposition of micrometer scale particles, resulting in a much higher gravimetric storage capacity.

Li-O2 are potentially low cost when employing inexpensive materials, such as carbon cathodes. When using HDN solvents, the capacity of Li-O2 batteries has been found to be correlated to the carbon cathode pore structure7,8,9, resulting in recent interest in carbons with high surface area and large pore volumes4,7,8. Among these carbon materials, carbon blacks have come to be commonly studied. However, carbon blacks, being highly disordered, are rich in defects. These defects are active sites for unwanted side reactions with the superoxide ion intermediate and rapid degradation of the cathode, resulting in short cycles lives10,11. Cathodes made with carbon nanomaterials possessing ordered structures, such as multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), are more resistant to degradation, while still possessing high surface areas and large pore volumes, resulting in excellent performance12,13,14,15. In addition, MWCNT’s support nanoparticle catalysts such as platinum16. However, the highly pure MWCNTs required for use in Li-O2 cells are prohibitively expensive and their production is environmentally deleterious17. Thus, inexpensive carbon nanostructures possessing similarly ordered structures with high surface areas, large pore volumes and pore sizes allowing for the facile transport of oxygen through the cathode are desirable for Li-O2 batteries7,8.

While Li-O2 batteries employing porous carbon cathodes can display impressive gravimetric capacities based on cathode material mass, the practical capacity is generally much lower. In HDN solvents, Li2O2 particles are deposited in the pores of the cathode material. Thus, “the capacity at a given initial porosity is determined by the degree of pore filling”6. Even assuming a closest pack structure fully occupying the pores, the packing efficiency is only 74%; in general, the pore occupation and packing efficiency are far less, leading to poor volumetric capacities. In addition, the mass of electrolyte in cathodes and the Li2O2 product must also be accounted for in practical cell level gravimetric capacity calculations, a correction that results in what has been termed “true capacity”6. Any porosity in the cathodes that is not utilized for Li2O2 storage decreases the practical capacity of the cathode. “For higher true capacities than intercalation electrodes, it is crucial to achieve an as high as possible packing density of Li2O2 and the minimize mass and volume”6. However, while Li2O2 particles packed to a maximum theoretical volume occupation could achieve true capacities that are higher than intercalation cathodes6, fully dense thick film formation fully filling the pores would further increase the potentially achievable true capacity by more than 35%. Optimally, thick film formation would occur on the surface of a low mass and volume cathode, not just in its pores, allowing capacities that could approach the theoretical limits of Li-O2 chemistry.

Carbon nanochains (CNCs) are carbon nanostructures with a chain-like morphology of interconnected multilayered carbon nano-onions in a stacked-cup CNT structure with pronounced exterior wall curvature. The surface area, pore size and total pore volumes can be rationally tuned over a wide range, allowing for the investigation of their effects on Li-O2 battery performance independent of the CNCs unchanging carbon morphology. In addition, the structural similarities and differences between CNCs and MWCNTs, provide an opportunity to gain insight into optimizing the design of a carbon cathode material for Li-O2 batteries.

The study described herein finds that the performance of binder-free CNC Li-O2 battery cathodes is superficially similar to that of multi-walled carbon nanotube (MWCNT) cathodes, as might be expected from their chemical and structural similarities. However, a more detailed analysis finds the bulk structural dissimilarities of the material yield tremendous performance advantages for CNCs. The peroxide storage in CNC cathodes is unique, to our knowledge never before reported in any other material, progressing from toroidal particles to thick, continuous films covering the cathodes. This results in very high volumetric energy density and, by limiting electrolyte mass in the cathode pores, to a greatly improved practical gravimetric capacity.

Results & discussion

After purification, CNC samples consist primarily of “sponge-like” agglomerates of intertwined twisted tubes (Fig. 1a, S3). In addition, numerous separated individual and small groups of CNCs are present (Figure S4). Prior to purification, unreacted starting material (biochar) is visible in SEM images (Figure S5). TGA thermograms run in air show a broad ~ 100% mass loss with an onset temperature of 510 ˚C for the unpurified material. Purification results in a dramatically sharper mass loss event and a reduction in the onset temperature to 324 ˚C.

The internal structure of CNC’s is analogous to MWCNT’s in that their walls consist of 10–15 layers of nested carbon sheets (Fig. 1b). However, whereas the carbon sheets which comprise MWCNT’s are concentric and ideally continuous along the entire length of each tube, the walls of CNC’s periodically curve inward, forming chains of interconnected ~ 20–50 nm hollow carbon onions (CNO), similar to bamboo-like or stacked-cup structured CNTs18,19, held together by shared walls. While TEM images show open passages between some adjacent onions, it is not clear if these openings extend the length of the chain. The chains are generally irregular spirals of several to 10’s of µm in length.

The interlayer wall spacings of the CNCs were measured by XRD (Fig. 2) and found to be in good agreement with TEM images, ~ 0.341 nm regardless of starting material or heating method (Table S3). However, the reflection is broad and asymmetric, extending as a shoulder to ~ 0.40 nm. This breadth could be due to an additional phase, however, it seems more likely that it is due to differences in the interlayer spacing of the various wall segments of the CNCs, being relatively straight over some portions and curved to various degrees over others, variation in the wall spacing with CNC diameter20 or intrawall separation21. In addition, the shape of the reflection changes with increasing FeCl2 content for samples made with cellulose, with a new peak growing in as a shoulder at lower d-spacing when made with 5 wt% FeCl2 (Figure S6). Deconvolution yields a peak with d ~ 0.335 Å in addition to that at ~ 0.34 Å, consistent with the formation of a second, more graphitic phase. This second phase can be seen in SEM images, appearing to be µm and sub-µm flakes of graphite (Figure S7).

Raman spectra of the CNC’s show the presence of both D and G bands at 1350 cm− 1 and 1589 cm− 1, respectively (Figure S8). The D-band results from the sp3 carbon present at edges while the G-band results from stretching vibrations of the plane of the sp2 carbon sheets, referred to as the E2g mode22,23,24. The ratio of the peak intensities, ID/IG, is a measure of the frequency of defects in layered carbon structures, being nearly zero for highly crystalline graphite25. The ID/IG ratio of CNC’s, ranging from ~ 1.6 to ~ 1.45 (Table S3), indicating a low but increasing degree of order with increasing wt% FeCl2, consistent with the highly curved nature of the carbon walls. The range of values observed are similar to those of CNTs with bamboo-like structure, with ID/IG ratios between 1.0 and 1.518,19,26.

The pore structures of the CNCs depend on the starting material and the heating method far more so than the FeCl2 content. CNCs display IUPAC Type IV hysteresis loops, behavior that is typical of mesoporous materials with “wedge-shaped pores”, those formed at the intersection of abutting materials (Figure S9 and S10)27. The pore diameter distribution of CNCs made from cellulose are broader and extend to larger diameters than those made from sawdust. The peaks of the distributions are below 20 nm in all cases, except those made from cellulose in the tube furnace (Fig. 3a and Table S4). This phenomenon is largely independent of catalyst loading (Fig. 3b, Figure S10b).

The surface area, total pore volume and weighted average pore diameters, summarized in Table S4, depend on the heating method, the type of biomass and catalyst loading used. Generally, the surface area of CNCs decreases with increasing catalyst loading, from ~ 250 m2/g when using 0.1 wt% FeCl2 and plateauing at ~ 200 m2/g with higher loading (Figure S10a). However, the surface areas for CNCs made from cellulose are anomalously low when made with 0.1 wt% FeCl2 (~ 220 m2/g), rising to an anomalously high surface area with 1.0 wt% FeCl2, and decreasing with higher catalyst loadings. The surface area of the CNCs made with cellulose are lower than those made from sawdust and 5.0 wt% FeCl2, regardless of heating method, presumably due to the observed growth of a second (graphitic) phase as discussed above, resulting in low surface area.

Surface area, while an important property of materials in many applications, is believed to play only a small role in determining the performance of Li-O2 cathodes, while pore volume and pore diameter are believed to be critical7,9. CNCs made from cellulose have larger total pore volumes than those made from sawdust at lower catalyst loadings, in particular those made in the tube furnace, decreasing to be nearly roughly equal with 5.0 wt% FeCl2 (Figure S10b, Table S4). Again, this decrease at high loadings may be at least in part due to the formation of a graphitic phase. Average pore diameters are significantly larger for CNC’s made from cellulose in the tube furnace, matched by those made from cellulose with a laser at 5.0 wt% FeCl2 (Figure S10c, Table S4).

CNC cathode performance

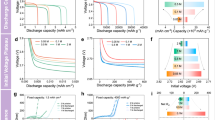

The full depth of discharge performance of Li-O2 cathodes made from sawdust in the laser (0.1 wt% FeCl2, CNC_1) and in the tube furnace (3 wt% FeCl2, CNC_2), and cellulose in the tube furnace (1 wt% FeCl2, CNC_3) is shown in Figure S11. The CNC samples were chosen to span a wide range of surface areas (247, 200 and 206 m2/g), total pore volumes (0.23, 0.53 and 0.74 cm3/g) and average pore diameters (~ 13 nm, 21 nm, and 39 nm), while avoiding preparations that resulted in the presence of a significant fraction of a second, graphitic phase. A previous study found that the discharge capacity of carbon cathodes increased with pore diameter but was insensitive to surface area and total pore volume7. We also find that the discharge capacity of our carbon cathodes, is not correlated to surface area (Figure S12) but increases monotonically in a roughly linear or parabolic fashion with total pore volume (Fig. 4a), and pore diameter (Fig. 4b).

Recharging cells after full depth of discharge frequently resulted in the formation of dendrites and consequent cell short circuiting. Stable, safe cycling was achieved by limiting the depth of discharge to 500 mAh/g, in agreement with previous studies28,29,30. The charge/discharge profiles were largely identical for all three samples. However, increasing the average pore diameter from 11 to 21 nm dramatically increased the cycle life from 23 to 37 cycles (Fig. 5). Only 2 cycles were added by further increasing the pore diameter to 39 nm.

Comparison of MWCNT and CNC cathodes

The structure of CNCs is in many respects similar to that of MWCNTs but they differ significantly in their surface area and porosity. The surface area of CNC_3 is more than 2 times and the pore volume 6% larger than MWCNTs (Figure S13), while the average pore diameter of MWCNTs is much greater than that of CNCs, as calculated from N2 isotherms (Table 1). In addition, CNCs have a larger total pore volume of pores with diameters less than 80 nm with a diminishing fraction as the pore diameter approaches 120 nm; the fraction of MWCNT pore volume grows roughly parabolically with increasing pore diameter. The pore volume of pores ≤ 80 nm in CNCs is 0.63 cm3/g, while that of MWCNTs is only 0.45 cm3/g, or 85 and 64% of the total pore volume less than 120 nm, respectively. A larger fraction of the pore volume of MWCNTs is provided by pores from 80 to 100 nm (> 21%) than for CNCs (< 7%), with the total pore volume less than 100 nm being only 13% more for CNCs than MWCNTs (0.68 and 0.60 cm3/g respectively). However, while CNCs are primarily mesoporous, MWCNTs are primarily microporous; the vast majority of its pores are much larger than can be measured by N2 isotherms and thought to provide little or no additional Li-O2 gravimetric capacity7, while having a markedly negative impact on volumetric capacity.

MWCNT cathodes have porous, fibrous surfaces (Fig. 6a). Discharge results in lithium peroxide toroidal particles forming in the interior, encapsulated by webs of nanotubes, with few or none on the outer surface of the electrode (Figure S14). The particles grow upon further discharge until they are ~ 1 μm in diameter. The particles never exhibit intergrowth, remaining distinctly individual rather than as a continuous mass, even after full discharge, and are predominately found in the interior, with few if any on the face, of the electrode (Fig. 6c). The fibrous network and high porosity that appears to span the depth of the electrode is still apparent after full discharge. With no obvious limitations to reactant transport, it has been suggested that the surface passivation prevents further discharge10,31,32. It should be noted that gravimetric capacity of MWCNT cathodes based on material mass greatly overstates their gravimetric capacity; the large galleries that are not filled by Li2O2 even after full discharge are not empty, but rather full of electrolyte, the mass of which diminishes the gravimetric capacity of the cell.

The surfaces of CNC cathodes are relatively uniform (Fig. 6b). In the early stages of discharge, toroidal lithium peroxide particles are seen to be uniformly distributed, but not completely covering, the surface of the CNC cathode, rather than in the pores (Figure S15). With further discharge, the lithium peroxide particles grow until they are ~ 2 μm in diameter, approximately twice the size observed with MWCNT electrodes, and almost completely coating the CNC cathode, but maintaining distinctly individual toroidal particles. Full discharge results in their intergrowth, forming a smooth, continuous, seemingly non-porous, thick film, in stark contrast to MWCNTs and, to our knowledge all other previously reported cathode materials (Fig. 6d). In addition, while the Li2O2 particles deposit in the pores of other cathode materials6,7, including MWCNTs as seen above, eventually clogging those pores, they deposit outside of the pores of the CNCs, some in void space between the agglomerates (Fig S16a), but primary as a ~ 20 μm film on cathode surface (Fig S16b). This suggests that the completed thick peroxide film acts as a diffusion barrier, preventing further discharge, although surface passivation cannot be ruled out.

Despite the dramatic difference in the peroxide growth morphology and coverage, the gravimetric discharge capacities of CNC and MWCNT electrodes are similar, 4870 ± 450 (in good agreement with the observed film thickness) and 5290 ± 630 mAh/g, respectively; however, the CNC electrodes are far denser than those made with CNT’s, yielding an average volumetric capacity that is nearly twice as large as that of MWCNTs (Fig. 7a; Table 1). While the pore volume measured by N2 adsorption of the CNCs is slightly larger than that of the MWCNTs, a significant portion of the porosity of the CNCs are from pores that are smaller than thought to be optimal. However, the total porosity ≤ 100 nm is modestly larger than that of MWCNTs, with much of the MWCNT porosity due to pores beyond the size range reported to be most effective7.

The gravimetric capacity of MWCNTs can be remarkably well estimated from its porosity measured by N2 adsorption. Previously, Ding et al. measured the capacity of carbonaceous materials, engineered by template to have with uniform pore sizes from ~ 2.4 to 100 nm7. The published data is well fit by an exponential function (Figure S17). Using the resulting fitting equation and the MWCNT porosity data (up to 113.5 nm pore diameter) yields a capacity of 5350 mAh/g, 1% larger than that measured in this study. The closeness of the agreement indicates that the majority of the porosity of MWCNT cathodes, pores that exceed the limit of N2 adsorption measurement, play little or no role in determining the capacity, although they may allow access to the active pores, those that have diameters of approximately 100 nm or less.

Estimating the capacity of CNCs in this manner is far less satisfactory, yielding only 3652 mAh/g (up to 112.3 nm pore diameter), 25% less than observed. This underestimation could be due to more effective utilization of small pores in the CNCs. While pore clogging was observed and thought to limit the capacity of small pores of the engineered porous carbons7, no similar obstruction of CNC pores was observed in this study. The absence of clogging of CNC pores may be due to their open structure, lacking the “bottle-necking” of the pores of the engineered porous carbons, allowing them to make a larger contribution to the total capacity.

Comparison of the capacities of CNCs and MWCNTs on the basis of the carbon mass neglects the contribution of the electrolyte in the pores to the total mass of the cathodes. Electrochemical activity is dependent on the presence of the electrolyte, an essential component that must be included when comparing Li-O2 cathodes. Corrections for electrolyte mass were made by calculating the total porosity of the cathodes from their masses and physical dimensions yielding electrode densities, subtracting the volume occupied by the CNCs and MWCNTs using the true density of MWCNTs (2.1 g/cm3) to yield total porosity and multiplying by the electrolyte density (1.194 g/cm3) to give its mass. The MWCNT cathodes are far less dense than those of CNCs (0.505 vs. 1.055 g/cm3) and more porous (1.51 vs. 0.47 cm3 of pore volume per g). MWCNT cathodes require electrolyte with nearly twice the mass of the dry electrode to fill (1.80 g electrolyte / g MWCNT) its pores, whereas CNC cathodes require approximately one-third of that value (0.563 g electrolyte / g CNC). Correcting for the mass of the electrolyte in the cathodes yields average discharge capacities of 3090 ± 180 and 1890 ± 300 mAh/g for CNCs and MWCNTs respectively.

While including the mass of electrolyte allows comparisons of porous Li-O2 cathodes, comparison to cathodes used with other battery chemistries requires further correction. For example, Li-ion batteries are assembled in a fully discharged state with the lithium ions contained in their cathodes. Li-O2 batteries are generally assembled in the fully charged state, without the mass of the Li discharge product accounted for in the cathode mass. Thus, one must include the mass of the dry cathode material, the electrolyte used to fill the cathodes pores and the mass of the Li2O2 discharge product to calculate their “true capacities” and enable comparison to Li-ion, and other, battery cathodes. Adjusting for the discharge product mass calculated from the discharge capacity assuming full conversion to stoichiometric Li2O2, yields true capacities of 845 ± 13 and 717 ± 42 for CNC and MWCNT cathodes respectively. While the CNCs obtain lower capacity per carbon mass, electrolyte accounts for less than half (16.9 ± 1.6%) that of the MWCNT (37.9 ± 2.5%) true cathode mass, resulting in 18% higher true capacity. It is of interest to note that carbon material is a minority component of both cathodes, 29.7 + 2.1 and 13.7 + 1.0% for CNC and MWCNTs respectively, illustrating the need for reporting performance based on the full cathode composition rather than just the dry active component.

The true capacity of the MWCNT cathodes is slightly larger than the capacity of Li2O2 spheres packed at full theoretical density, 700 mAh/g,6 which is not consistent with porosity measurements and SEM observations. The volume required to contain all of the Li2O2 product of full discharge is 97% of the initial porosity of the MWCNT cathodes, implying that it should essentially completely fill all pores as dense bulk solid. However, this is clearly not the case as SEM images of fully discharged MWCNT cathodes (Fig. 6a and S18) show a high degree of porosity, including a myriad of small pores surrounding the product particles and, in addition, the presence of very large pores. The porosity indicates that the cathode has swollen as a result of electrolyte uptake and/or due to product formation during discharge, which is not accounted for in our calculations. While density measurements of fully discharged cathodes could potentially allow better calculations, unfortunately, they are unreliable due to the reactivity of the product and difficulty in ensuring the removal of all of the electrolyte. However, it is clear that the discharged MWCNT cathodes are highly porous, and that the true capacity calculated from the discharge capacity and initial porosity are significantly overstated.

The true capacity of the CNCs is ~ 21% larger the theoretical limit of close-packed Li2O2 spheres. While there is no clear evidence of swelling of the CNCs, it cannot be ruled out. However, any swelling is clearly much less than that which occurs in MWCNT cathodes, and the large true capacity can be accounted for by the observed storage of the product as bulk films rather than toroidal particles.

Limiting the depth of discharge to 500 mAh/g resulted in stable cycling for the MWCNT as well as the CNC cathodes. The difference between the charge and discharge potentials was, within the limits of uncertainty, essentially identical (Figure S19), with CNC’s generally exhibiting slightly higher charge and discharge potentials (Figure S20). The average cycle life of the CNCs cathodes is 19% longer than that of CNTs (Fig. 7b; Table 1). It is not clear why the cycle life of CNCs cathodes is longer than that of MWCNTs, however, the electrode swelling of MWCNTs during cycling may result in higher mechanical stress than experienced by CNCs, perhaps resulting in more rapid cathode deterioration, or the formation of a passivation layer electronically isolating the cathode from the current collector.

While the capacities of the cathodes can be correlated to their mesoporosity, the location and structure of these pores is not immediately apparent. Pores provide regions of high intermediate concentrations, increasing the rate of formation of stable Li2O2 nuclei, thus limiting the reaction of its embryos or superoxide with electrolyte. The good agreement between the mesopore volume of the MWCNT cathodes and their capacity indicates that the interiors of the tubes are largely not responsible. Alternatively, the intersections of the exteriors of the tubes could result in the full range of mesoporosity measured, and provide pores with an influx of intermediates from multiple sides and consequently higher concentration and nucleation probability. CNCs interiors are likely largely not responsible for the observed capacity as they unlikely to account for the vast majority of the observed porosity, particularly the larger pores that appear to be most active. In addition, one would expect pore clogging to occur in the openings as was observed in engineered nanoporous carbons22, however, none was observed. Thus, as with MWCNTs, the intersections of the exteriors of the CNCs are the likely pores that are responsible for the vast majority of Li2O2 formation.

The initial formation and deposition of toroidal Li2O2 particles is very similar for MWCNT and CNC cathodes, but thick film formation is only observed in the later as the discharge progresses. While differences in the MWCNT and CNC structures may account for this deviation, it seems more likely that the progression from toroids to thick films is due to the high density of pore sites in the CNC cathodes. Deposition in either case occurs near the location of the pores and with the total discharge product (capacity) being practically identical, the higher density of formation sites in the CNCs leads to closer Li2O2 particle separation. As discharge proceeds, the particles grow further, narrowing their separation, leading to further growth by embryonic product addition, obscuring the toroids and co-joining them into a thick film.

These observations suggest structural characteristics that could lead to thick film formation and high true and volumetric capacities with other materials. The active pores in MWCNTs and CNCs are free of bottle-necking, consisting of the intersections of tubes that diverge, limiting clogging. Large galleries between the pores seem counter-productive, limiting volumetric capacity, and by requiring significant additional electrolyte, lower true capacities. In addition, the galleries increase the distance between pores and the pores to the surface, resulting in isolated, interior Li2O2 particle, rather than surface thick film, formation. Finally, the cathode material should be structurally resistant to swelling, maintaining the close separation of the pore sites and limiting additional electrolyte uptake.

Conclusions

CNCs, material structurally akin to MWCNTs, can be synthesized from biomass by simple, rapid methods, without the expense or environmental impact of the CVD methods used to make the later. The properties of CNCs, including surface area, porosity and average pore diameters, can be rationally controlled by variations of the synthetic parameters. The surface areas of CNC’s made from sawdust are higher than those made from cellulose using equivalent catalyst (FeCl2) loading and heating method. The CNC pore structure is found to be dependent on the selection of starting material, heating method, and wt% of catalyst. Of note, CNCs made from cellulose in the tube furnace showed larger pore volumes and pore diameters than those made with a laser or sawdust by either heating method. Overall, CNCs could be made with pore volumes and average pore diameters ranging from 0.23 to 0.77 cm3/g and 11–40 nm, respectively, depending on the synthesis conditions selected.

The relationships between average pore diameters, total pore volume and surface area and Li-O2 cathode performance were investigated by testing cathodes made with CNCs that widely differed in these characteristics. It was found that both full depth of discharge capacity and limited depth of discharge cycling lifetimes improved with increasing pore diameter and pore volume. Isolating the roles of pore diameter and pore volume was not possible because CNCs with larger pore diameters always resulted in larger pore volumes as well.

Initial discharge product formation with MWCNT and CNC Li-O2 cathodes results in toroid formation, forming inside the pores of the former but on the surface of the latter. The toroids remain distinctly separated, entangle in the pores of MWCNT cathodes even after full discharge, with notable cathode swelling preserving much of its macroporosity. In contrast, toroid form on the surface of CNC cathodes, with little or no swelling observed, merging to completely cover the cathode with a thick, dense Li2O2 film.

Li-O2 cathodes made from CNCs have nearly identical full depth of discharge gravimetric capacity as those made with MWCNTs, while having a significantly longer limited depth of discharge cycle life. Correcting for the mass of electrolyte filling the cathode void space greatly favors CNCs with 63% higher gravimetric discharge capacity than MWCNTs, while further correction for Li2O2 mass results in a more modest, 18% advantage in true capacity (845 ± 13 and 717 ± 42 respectively). Finally, CNC cathodes are substantially denser than those of MWCNT’s, resulting in more than twice the volumetric capacity for full discharge. It is proposed that the advantages of CNCs over the structurally similar MWCNTs arises from the much higher density of active pores that are sufficiently open to limit blockage, the close proximity of these pores to the surface and the lack of large pores into which the toroidal particles could deposit, resulting in surface rather than interior product storage, transitioning to thick film formation as the discharge proceeds.

Methods

Materials

All materials are used as received unless stated otherwise. Sawdust (System Three Resin Inc Wood Flour) and cellulose (FMC BioPolymer) were used as the biomass starting materials. Iron (II) chloride tetrahydrate used as the catalyst was purchased from STREM (99%, product no. 93-2632). Nitric acid purchased from Millipore Sigma (GR ACS, product no. NX0409-2) was used for CNC purification. LiNO3 from Alfa Aesar (99.98% metal basis, product no. 10985), and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) from Fischer (99.9%, product no. D139-1) were used to make the electrolyte. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (> 95wt%, SKU # 030103), 10–20 nm in diameter and 10–30 μm in length, were purchased from Cheaptubes.com. Carbon Fiber Paper (Porous C)–EQ–bcgdl-1400 S-LD and coin cells (CR2016) were purchased from MTI Inc. Whatman glass microfiber filters (Grade GF/D, CAT no. 1823 − 150) were purchased through Millipore Sigma.

CNC synthesis

Sawdust (System Three Resin Inc Wood Flour) or cellulose (FMC BioPolymer) was mixed with FeCl2·4H2O (99%, Strem Chemicals), the wt % calculated on FeCl2 basis, with total mass of 8 g and loaded into a hardened steel cup (80 mL, Fritsch GmbH) with ten balls (hardened steel, 1 cm diameter) and milled at 300 rpm for 30 min using a planetary ball mill (Pulverisette 6, Fritsch GmbH). The FeCl2 impregnated sawdust or cellulose was then pressed at 11,000 lbs (35,500 PSI, Carver 3851 benchtop laboratory press) into a 20 mm diameter pellet.

CNC synthesis using a tube furnace

Pellets were placed inside a quartz tube inside a Thermo Scientific Lindberg/Blue M TF55030A tube furnace and centered so that pellets sat in the middle of the furnace. Argon gas was flowed through the quartz tube at 150 mL/min for several minutes before heating to allow the gas flow to stabilize. The pellets were then heated to 1000 ºC at 10 ºC/min and held at this temperature for 20 min. The pellets were then allowed to cool to room temperature while under the argon atmosphere in the tube furnace.

CNC synthesis using a laser

A 21/64” hole was drilled in each pellet using a Ryobi drill (DP102L benchtop). The pellets were then charred by placing them in a quartz tube inside a Thermo Scientific Lindberg/Blue M TF55030A tube furnace and centered so that pellets sat in the middle of the furnace. Argon gas was then flowed through the quartz tube at 150 mL/min for several minutes before heating, to allow the gas flow to stabilize. The pellets were then heated to 400 ˚C at 10 ˚C/min and held for 20 min. After charring and cooling, the pellets were skewered in a stack by a 1/4” stainless-steel rod and suspended vertically in a four-way cross chamber. The rod was secured to and fed into the chamber by a stepper motor (STM-23, Applied Motion Products) through a flange at the top of the cross that was equipped with an Ultra-torr vacuum fitting. The chamber was evacuated to 10− 3 Torr and then kept at 0.5 Torr with flowing N2 gas. The pellets were rotated for one full rotation (48 sec/rotation) while being irradiated through a ZnSe window (Design Research Optics) with a 10.6 µm CO2 laser at (60 W, Firestar t60, Synrad Inc.) focused to a 2 mm diameter spot. Alternatively, synthesis of CNCs using an ytterbium fiber laser model YLR-1000-MM-WC at 60 watts with wavelength of 1070 nm was also investigated. Samples made from the ytterbium fiber laser show smaller surface areas, pore volumes, and pore diameters than those made from the CO2 laser. Differences between samples made from the two different lasers are shown in Figure S1 and Table S1.

Purification

After heating, the pellets were ground into powder with a mortar and pestle, suspended (10 mg/mL) in nitric acid (ACS grade, Millipore Sigma) and heated to reflux for 4 h to remove amorphous carbon. The CNCs were isolated by vacuum filtration, rinsed with distilled water and dried overnight at 120 ºC. CNCs were then further purified by microwave digestion (PreeKem WX-6000) in nitric acid (10 mg/mL) for 30 min at 180 ˚C. Finally, the CNCs were isolated by vacuum filtration, rinsed with distilled water and dried overnight at 120 ºC. Yield of CNC’s recovered after purification are listed in Table S2.

Characterization

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed using a Perkin Elmer Pyris 1 TGA. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were obtained using a FEI Teneo LV FEG microscope and a FEI Talos™ F200X microscope, respectively. Powder X-ray diffractograms were obtained using a Bruker D2 Phaser x-ray diffractometer (Cu-Kα radiation). Raman spectra of the CNCs were obtained with a LabRAM HR spectrometer using a laser excitation wavelength of 532 nm.

Nitrogen adsorption isotherms were measured using a Micrometrics Tristar 3000 Surface Area and Porosity Analyzer. Prior to analysis, CNC samples were dried under vacuum at 150 ºC for one hour followed by 350 ºC for three hours using Micrometric VacPrep 061 sample degassing system. The surface area was calculated using the Braunauer-Emmet-Teller (BET) method, the pore volume and pore size distribution (PSD) was calculated using the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda method.

CNC cathode preparation

CNCs were suspended in isopropyl alcohol (IPA, VWR Chemicals 99.5%) and sonicated for 30 min to make a suspension with a CNC concentration of 9 mg/mL. Carbon fiber paper (CFP) current collectors (MTI Inc.), from which carbon black was removed by repeated sonication in IPA followed by abrasion, were placed in half of a CR2016 coin cell. The CNC solutions were drop cast onto the CFPs and the IPA was removed by evaporation. The cathodes were massed and when necessary, more CNC solution was drop cast onto the cathode until the target loading of 1.5 mg/cm2 (3.0 mg CNC) had been reached. The CNC cathodes were dried in a 120 ˚C oven overnight. The CNC cathodes were then pressed between two sheets of aluminum foil at 18,000 lbs (58,000 PSI).

MWCNT cathode preparation

MWCNTs were sonicated in IPA for 30 min to form a suspension with a concentration of 0.33 mg/mL. The suspension was then poured through CFP, from which carbon black had been removed, stacked on top of a PTFE membrane filter (47 mm diameter, 0.45 μm pore size, Simsii Inc.), leaving a layer of MWCNTs on top of the CFP. The sample was then dried at 120 ˚C overnight. Electrodes, 1.6 cm in diameter, were punched out of the film (MSK-T-07 Precision Disc Cutter, MTI Inc.) and pressed between two sheets of aluminum foil at 6,000 lbs (19,400 PSI). The loading of the MWCNT cathodes was 1.5 mg/cm2 (3.0 mg MWCNT).

Cell assembly

Nine holes (1 mm diameter) were punched into the cathode side of coin cells (CR2016, MTI Inc.) to allow oxygen flow during cell cycling. The cells were assembled in an Ar filled glove box, using lithium metal chips (15.6 mm diameter and 0.45 mm thick, 99.9%, MTI Inc.) as the anode and glass microfiber filter (Grade GF/D, Whatman Inc.) as the separator saturated with 200 µL of 0.1 molar ratio LiNO3 (99.98%, Alfa Aesar) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 99.9%, Fisher Inc.) electrolyte.

Electrochemical cell testing

The cells were placed in air-tight custom-built PVC containers (Figure S2), purged with a flow of O2 (99.995%, Robert’s Oxygen Company) for 10 min, and then maintained at 5 psi. The cells were held for 4 h at OCV and then cycled at a current density of 0.2 mA/cm2. Cells were discharged from OCV (~ 2.8–3.0 V) to 2.0 V to measure the maximum capacity that the CNC and MWCNT cathodes could achieve. Following the practice of previous studies,37–39 multicycle testing was performed with a limited depth of discharge (500 mAh/g discharge/charge) to avoid dendrite formation with CNC and MWCNT cathodes.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bruce, P. G., Freunberger, S. A., Hardwick, L. J. & Tarascon, J. M. Li–O2 and Li–S batteries with high energy storage. Nat. Mater. 11 (1), 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat3191 (2012).

Tan, P. et al. Advances and challenges in lithium-air batteries. Appl. Energ. 204, 780–806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.07.054 (2017).

Aurbach, D., McCloskey, B. D., Nazar, L. F. & Bruce, P. G. Advances in understanding mechanisms underpinning lithium–air batteries. Nat. Energy. 1 (9), 16128. https://doi.org/10.1038/nenergy.2016.128 (2016).

Cao, D., Bai, Y., Zhang, J., Tan, G. & Wu, C. Irreplaceable Carbon boosts LiO2 batteries: from mechanism research to practical application. Nano Energy. 89, 106464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2021.106464 (2021).

Greenwood, M., Wentker, M. & Leker, J. A bottom-up performance and cost assessment of lithium-ion battery pouch cells utilizing nickel-rich cathode active materials and silicon-graphite composite anodes. J. Power Sources Adv. 9, 100055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powera.2021.100055 (2021).

Mahne, N., Fontaine, O., Thotiyl, M. O., Wilkening, M. & Freunberger, S. A. Mechanism and performance of lithium–oxygen batteries – a perspective. Chem. Sci. 8 (10), 6716–6729. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7SC02519J (2017).

Ding, N. et al. Influence of carbon pore size on the discharge capacity of Li–O 2 batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2 (31), 12433–12441. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4ta01745e (2014).

Wang, F., Li, X., Hao, X. & Tan, J. Review and recent advances in mass transfer in positive electrodes of Aprotic Li–O2 batteries. Acs Appl. Energy Mater. 3 (3), 2258–2270. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaem.9b02237 (2020).

Xiao, J. et al. Optimization of Air Electrode for Li/Air Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 157 (4), A487. https://doi.org/10.1149/1.3314375 (2010).

Itkis, D. M. et al. Reactivity of Carbon in Lithium–oxygen battery positive electrodes. Nano Lett. 13 (10), 4697–4701. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl4021649 (2013). PMID – 24004050.

Thotiyl, M. M. O., Freunberger, S. A., Peng, Z. & Bruce, P. G. The carbon electrode in nonaqueous Li–O 2 cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (1), 494–500. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja310258x (2012). PMID – 23190204.

Bae, Y. et al. Tuning the carbon crystallinity for highly stable Li–O2 batteries. Chem. Mater. 28 (22), 8160–8169. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b02489 (2016).

Nomura, A., Ito, K. & Kubo, Y. C. N. T. Sheet air electrode for the development of ultra-high cell capacity in Lithium-Air Batteries. Sci. Rep-uk. 7 (1), 45596. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45596 (2017).

Lim, H. D. et al. Enhanced Power and rechargeability of a Li – O2 battery based on a hierarchical-fibril CNT electrode. Adv. Mater. 25 (9), 1348–1352. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201204018 (2013).

Chen, Y. et al. Multi-walled carbon nanotube papers as binder-free cathodes for large capacity and reversible non-aqueous Li–O 2 batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A. 1 (42), 13076–13081. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3ta11792h (2013).

Li, J. et al. An effective Integrated design for enhanced cathodes of Ni Foam-supported Pt/Carbon nanotubes for Li–O2 batteries. Acs Appl. Mater. Inter. 6 (15), 12479–12485. https://doi.org/10.1021/am502411y (2014). PMID – 25010947.

Sengupta, J. Handbook of nanomaterials for Industrial applications. Arxiv 172–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-813351-4.00010-9 (2018).

Dong, Q. et al. Uniform bamboo-like N-doped carbon nanotubes derived from a g-C 3 N 4 substrate grown via anchoring effect to boost the performance of metal–air batteries. Acs Appl. Energy Mater. 3 (11), 11213–11222. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaem.0c02146 (2020).

Kecsenovity, E., Fejes, D., Reti, B. & Hernadi, K. Growth and characterization of bamboo-like carbon nanotubes synthesized on Fe–Co–Cu catalysts prepared by high‐energy ball milling. Phys. Status Solidi B. 250 (12), 2544–2548. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssb.201300075 (2013).

Singh, D. K., Iyer, P. K. & Giri, P. K. Diameter dependence of interwall separation and strain in multiwalled carbon nanotubes probed by X-ray diffraction and Raman scattering studies. Diam. Relat. Mater. 19 (10), 1281–1288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diamond.2010.06.003 (2010).

Futaba, D. N., Yamada, T., Kobashi, K., Yumura, M. & Hata, K. Macroscopic wall number analysis of single-walled, double-walled, and few-walled carbon nanotubes by X-ray diffraction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133 (15), 5716–5719. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja2005994 (2011).

Bokobza, L., Bruneel, J. L. & Couzi, M. Raman spectra of carbon-based materials (from Graphite to Carbon Black) and of some silicone composites. C J. Carbon Res. 1 (1), 77–94. https://doi.org/10.3390/c1010077 (2015).

Wang, Y., Alsmeyer, D. C. & McCreery, R. L. Raman spectroscopy of carbon materials: structural basis of observed spectra. Chem. Mater. 2 (5), 557–563. https://doi.org/10.1021/cm00011a018 (1990).

Ivanova, M. V., Lamprecht, C., Loureiro, M. J., Huzil, J. T. & Foldvari, M. Pharmaceutical characterization of solid and dispersed carbon nanotubes as nanoexcipients. Int. J. Nanomed. 7, 403–415. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijn.s27442 (2012). PMID – 22334774.

Banek, N. A., Abele, D. T., McKenzie, K. R. Jr. & Wagner, M. J. Sustainable conversion of lignocellulose to high-purity, highly crystalline flake potato graphite. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6 (10), 13199–13207. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b02799 (2018).

Ivanova, L., Loureiro, Huzil, J. T. & Foldvari, M. Pharmaceutical characterization of solid and dispersed carbon nanotubes as nanoexcipients. Int. J. Nanomed. 7, 403–415. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S27442 (2012).

Sing, K. S. W. Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems with special reference to the determination of surface area and porosity (recommendations 1984). 57 (4), 603–619. DOI: (1985). https://doi.org/10.1351/pac198557040603

Huang, Z. et al. Li–O2 battery cathode with vertical mass/charge transfer pathways. J. Mater. Chem. A. 7 (7), 3000–3005. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9TA00017H (2019).

Chawla, N., Chamaani, A., Safa, M. & El-Zahab, B. Palladium-filled carbon nanotubes cathode for improved electrolyte stability and cyclability performance of Li-O2 batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 164 (1), A6303. https://doi.org/10.1149/2.0491701jes (2017).

Cho, Y. S. et al. Enhancing the cycle stability of Li–O2 batteries via functionalized carbon nanotube-based electrodes. J. Mater. Chem. A. 8 (8), 4263–4273. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9TA12116A (2020).

Belova, A. I., Kwabi, D. G., Yashina, L. V., Shao-Horn, Y. & Itkis, D. M. Mechanism of Oxygen reduction in Aprotic Li–Air batteries: the role of Carbon Electrode Surface structure. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121 (3), 1569–1577. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b12221 (2017).

Liu, Y. et al. Understanding and suppressing side reactions in Li–air batteries. Mater. Chem. Front. 1 (12), 2495–2510. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7QM00353F (2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.D.W. conducted the studies of Li-O2 batteries while K.R.M. contributed to the development of CNC synthesis. M.J.W. supervised the research and was the primary author of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Womble, M.D., McKenzie, K.R. & Wagner, M.J. Thick film formation on Li-O2 cathodes – breaking the true capacity barrier. Sci Rep 15, 5868 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89655-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89655-0