Abstract

We investigated associations of a broad biomarker panel with cognitive decline in atrial fibrillation (AF) patients to characterize possible mechanisms. We enrolled 1440 AF patients with available baseline biomarkers and cognitive testing by the Montreal Cognitive assessment (MoCA) score at inclusion and at ≥ 2 yearly follow-ups. We investigated the associations of biomarkers with cognitive decline in univariate logistic regression models, LASSO regression analysis and built a combined model. Mean age was 72 years, 75% male, 47% paroxysmal AF. Over 4 years, 93 patients (6.5%) had cognitive decline. These patients had more often permanent AF (32.3 vs 21.5%, p = 0.007) and more often a history stroke (23.7 vs 11.2%, p < 0.001), but similar baseline MoCA scores (24.9 vs 25.3 points, p = 0.22) and anticoagulation rates (93.5 vs 89.5%, p = 0.29). The three biomarkers with the highest univariate AUC for cognitive decline were GDF-15 (0.67 [0.62–0.72]), Cystatin C (0.67 [0.61–0.72]) and high-sensitivity Troponin T (hs-TnT) (0.65 [0.60–0.70]). In LASSO regression analysis, the best cross validation included GDF-15, GFAP, ESM-1, NfL and ALAT. The combined prediction model with the highest AUC of 0.73 (0.68–0.78) included IGFBP-7, GDF-15, Cystatin C, hsCRP, ALAT, GFAP, ESM-1 and FGF23. Over 4 years, 6.5% of AF patients had cognitive decline despite a high rate of anticoagulation. Inflammation, neuronal damage, and increased amyloid-beta might be important non-ischemic mechanisms of cognitive decline in AF patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) are at an increased risk of cognitive decline compared to the general population1,2. As AF is the most common sustained arrhythmia, accelerated cognitive decline in these patients is a major public and individual health burden in an ever aging society3,4. We have previously shown that covert brain infarcts, that occur despite oral anticoagulation, may play a relevant role in the cognitive decline of patients with AF5,6. However, additional underlying mechanisms or risk factors for loss in cognition in these patients are still incompletely understood.

Besides direct, ischemic brain damage, other pathophysiological processes, including for example inflammation, cell regulation, cardiac function, lipid regulation, renal function and thyroid hormones, might also play key roles in cognitive decline in AF patients7,8,9. Biomarkers may offer an accessible and non-invasive opportunity to better understand the roles of these potential risk factors and mechanisms underlying cognitive decline. Their knowledge of and improved characterisation will be necessary for the development of future, preventive treatment strategies.

We therefore aimed to investigate the associations of a wide biomarker panel with cognitive decline over time in a large cohort of patients with AF.

Methods

Patient population

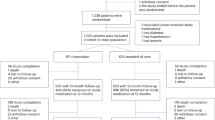

The present study is a sub-analysis of the Swiss Atrial Fibrillation (Swiss-AF) study, an ongoing, prospective cohort study at 14 centres in Switzerland5,6,10. Main inclusion criteria of Swiss-AF were previously documented AF and an age ≥ 65 years. For a pre-specified subset to assess the effect of AF on individuals in the active workforce, a small number of participants aged 45–64 years was enrolled. Exclusion criteria were the inability to give informed consent or secondary AF due to reversible causes. Enrolment of participants with an acute illness was delayed for 4 weeks to allow for resolution of the acute condition. Of the 2,415 participants included in Swiss-AF, we excluded participants with no baseline cognitive assessment (n = 4), without any follow-up cognitive assessment (n = 218) and without any baseline biomarker measurements (n = 23), leaving 2,170 (89.9%) participants. In order to assess cognition over time, we further excluded 662 participants without cognitive assessment at 1, 2 and 3 years of follow-up. As described below, we further excluded 68 participants due to discrepant cognitive slopes over 3 years and over the whole follow-up period, leaving a final study population of 1,440 (59.6%) participants. The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki, the study protocol was approved by the local ethics committees and informed written consent was obtained from each participant.

Clinical variables

At baseline and during yearly in-person study visits, trained study personnel acquired information about patient demographics, prior medical history, interventional and medical treatment and risk factors by standardized case report forms. The mean of three consecutive blood pressure measurements was used for all analyses. AF was categorized according to guideline recommendations at the time of study inception into paroxysmal, persistent or permanent11.

Biomarker assessment

Biomarkers were selected based on biological plausibility, prior literature, and availability. We included biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress12,13,14,15, myocardial injury and strain13,16,17,18,19, vascular damage20,21, renal dysfunction22, thyroid function23,24,25, lipid metabolism26,27, and cerebral damage28,29,30, that were previously associated with AF and/or cognition. Levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), creatinine, cystatin C (CysC), growth differentiation factor-15 (GDF-15), high-sensitivity Troponin T (hs-TnT), N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), D-Dimer, Alanine Aminotransferase (ALAT), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free Thyroxine (fT4), Cancer Antigen 125 (CA125), high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein, lipoprotein a, Triglycerides and cholesterol were determined by commercially available assays (cobas c 311 and Elecsys®; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), bone morphogenetic protein 10 (BMP10), Dickkopf-3 (DKK3) and fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) were determined by robust prototype assays (robust prototype Elecsys® assays; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Pre-commercial assays were used for angiopoietin-2 (ANG-2), endothelial cell-specific molecule-1 (ESM-1), heart fatty-acid-binding protein-3 (hFABP-3), insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-7 (IGFBP-7) and osteopontin (OPN) (high-throughput Elecsys® immunoassays; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). For detection of these parameters, sandwich-immunoassays were developed for the cobas Elecsys® ECLIA platform applying monoclonal antibodies developed for specific detection of the respective protein biomarker. Serum neurofilament light protein (NfL) was measured using a previously described ultrasensitive single‐molecule array assay31.

If the biomarker level was below the lower limit of detection or quantification, we imputed half of the respective limit. If the biomarker level was above the upper limit of quantification, we imputed the upper limit. To address missing biomarker values, we used a random forest-based imputation method (missRanger package in R), which employs a random forest-based imputation method. We included Age, Sex, and BMI as additional predictors to enhance the accuracy of the imputed values. This approach leverages the relationships between variables, offering a robust and comprehensive method for estimating missing data compared to traditional techniques.

Cognitive testing

Centrally trained study personnel performed standardized neuro-cognitive testing annually. We used the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) to assess cognition32. It evaluates visuospatial abilities, short-term memory, abstraction, language and executive functions divided into 13 individual test sections. Obtainable scores range from 0 to 30 points with higher scores indicating better cognitive functioning across all domains. One point is added to the total test score if the patient had 12 years or less of formal education. A score below 26 points is considered to indicate mild cognitive impairment.

Cognitive decline

The primary endpoint for this analysis was cognitive decline. In order to assess cognitive decline over time, we calculated cognitive slopes for each patient based on yearly cognitive assessments over 3 years. We used 3-year slopes over single measurements to control for outliers at a single follow-up visit, for example when a patient had a “bad day” at their study visit. We then assessed the slopes of participants with a 1 standard deviation (SD) decrease in their MoCA score over 3 years, compared to those without a 1 SD decrease. Participants with a 1 SD decrease had a median slope of − 0.21 and participants without a 1 SD decrease had a median slope of 0.17. We therefore defined participants with cognitive decline as those with a 3-year slope below − 0.2, meaning their MoCA score decreased by − 0.2 per year, and those without cognitive decline with a 3-year slope above − 0.2. We further assessed cognitive slopes over all available follow-ups. We categorized participants with 3-year slopes below − 0.2, but with the overall, available slope above − 0.2 as inconclusive and excluded them (n = 68). Figure 1 shows three examples of patients with cognitive decline both in their 3-year slope and overall slope and three patients without cognitive decline.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were stratified by presence or absence of cognitive decline. Continuous variables were presented as means (standard deviations) and categorical variables were shown as frequencies (percentage). To investigate the associations of biomarkers with cognitive decline, we used a series of statistical analyses. First, we used univariate logistic regression models to assess the relationship between each biomarker and cognitive decline. Specifically, we calculated the area under the curve (AUC) for each biomarker’s predictive performance. Second, we applied a LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) regression analysis to identify the most relevant biomarkers associated with cognitive decline. This approach allowed us to determine the optimal combination of biomarkers by minimizing the impact of irrelevant variables. We plotted the lambdas and their corresponding coefficients to visualize the selection process. Third, we constructed a combined biomarker model using stepwise selection regression analyses. To identify the most significant predictors for our multivariate model, we applied a stepwise model section method based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). This method iteratively adds or removes (both directions) predictors, aiming to balance model fit and complexity. By using this method, we systematically evaluated the contribution of each variable, retaining those that provided the best explanatory power for the outcome while minimizing overfitting. This approach allowed us to refine our model by including only the most relevant variables, enhancing its predictive accuracy and interpretability. We then calculated the AUC for this multi-marker model, representing its predictive ability for cognitive decline. We did not adjust our analyses for clinical confounders as we specifically aimed to explore potential mechanisms displayed by biomarkers only.

A two-sided p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 or R 4.0.

Results

Overall, mean age was 71.9 (8.3) years, and 1,080 (75.0%) participants were male. At enrolment, 674 (46.8%) participants had paroxysmal AF, 173 (12.0%) had a prior stroke, 1,293 (89.8%) were anticoagulated and the mean baseline MoCA score was 25.3 (2.9) points.

Over a median (interquartile range) follow-up time of 4 (1.9, 7.4) years, 93 (6.5%) participants experienced cognitive decline. Detailed information on the baseline characteristics stratified by presence or absence of cognitive decline over time are shown in Table 1. Compared to participants without cognitive decline, participants with cognitive decline were older (77.1 vs 71.5 years, p < 0.001), had more often permanent AF (32.3 vs 21.5%, p = 0.007), more often a history of myocardial infarction (22.6 vs 14.2%, p = 0.04) and prior stroke (23.7 vs 11.2%, p < 0.001). Baseline MoCA scores (24.9 vs 25.3 points, p = 0.22) and anticoagulation rates (93.5 vs 89.5%, p = 0.29) were similar between groups.

Baseline biomarker levels

Biomarker levels at baseline of participants with and without cognitive decline are shown in Table 2. Participants with cognitive decline had higher levels of brain specific biomarkers (NfL, GFAP), biomarkers of renal function (Creatinine, Cystatin C and Dickkopf-3), cardiac strain (BNP, BMP-10, hFABP, IGFBP-7) and biomarkers of cell regulation (IGFBP-7, Osteopontin, ESM-1). Some (GDF-15) but not all inflammatory biomarkers were also higher in participants with versus without cognitive decline. We did not find between group differences in biomarker levels of thyroid function, lipid metabolism or cardiac injury.

Biomarker and cognitive decline

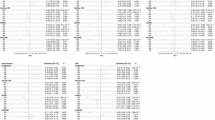

The univariate, discriminatory performances of all biomarker and age for cognitive decline are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 2. Overall, age had the highest AUC (0.70 [0.64–0.75]). The five individual biomarker with the highest AUCs in descending order were: GDF-15 (0.67 [0.62–0.72]), Cystatin C (0.67 [0.61–0.72]), hs-TnT (0.65 [0.60–0.70]), NfL (0.64 [0.58–0.70]) and ESM-1 (0.64 [0.58–0.70]).

Figure 3 shows the LASSO regression analysis with the lambdas and the corresponding coefficients of each biomarker. At the first line with the minimal value of lambda, that results in the best cross validation, GDF-15, GFAP, ESM-1, NfL and ALAT were included. At the second line with the largest lambda (within 1 standard error of the minimal lambda), corresponding to a higher penalized model, only GDF-15 was still included.

LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) regression analysis for biomarkers and cognitive decline. The lambdas (x axis) and the corresponding coefficients (y axis) for the different variables are plotted. The curves represent the change of the coefficient for each lambda and decrease with the increase of the penalty term (lambda). The first line is the minimal value of lambda that results in the best cross validation result. The second line is the largest lambda within 1 standard error of the minimal lambda. This lambda corresponds to a higher penalized model.

The eight biomarker that were selected in the stepwise, multivariate model were IGFBP-7, GDF-15, CysC, hsCRP, ALAT, GFAP, ESM-1 and FGF23. The corresponding estimates are shown in Fig. 4. The AUC (95% CI) for cognitive decline of this biomarker combination was 0.73 (0.68–0.78) (Fig. 4, right).

Discussion

In a large, prospective cohort of patients with AF, 6.5% developed cognitive decline over a follow-up of 4 years despite a high rate of anticoagulation. Our biomarker analyses suggest three main non-ischemic mechanisms for cognitive decline in patients with AF: Inflammation, neuronal damage, and increased amyloid-beta.

Considering the already large and further increasing AF patient population3,4, our observed rate of cognitive decline over a mid-term follow-up period may pose a relevant public and individual health burden in the long term. A pooled, prospective analysis of the ONTARGET and TRANSCEND trials investigated cognitive decline (defined as a decrease of ≥ 3 points in the Mini–Mental State Examination) in 31,506 patients with a mean age of 67 years and showed an incidence rate of 16.6% in patients without AF and 20.3% in patients with AF over a median follow-up of 4.7 years33. These higher incidence rates compared to our current results may be due to differences in patient characteristics and a less strict definition of cognitive decline, but similarly highlight the increased incidence in AF patients. While anticoagulation attenuates the risk for cognitive decline in patients with AF, it does not avoid it34. This residual risk may be due to covert ischemic lesions occurring despite anticoagulation6, part of it might also be due to non-ischemic mechanisms like inflammation, cell regulation or primary neurodegeneration.

Our biomarker analyses provide insights into potential non-ischemic mechanisms. GDF-15 had the highest individual discriminatory performance for cognitive decline and was the only selected biomarker in the higher penalized model in LASSO analysis. GDF-15 is part of the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β superfamily and functions as a regulatory cytokine for cell cycle control, development and repair processes in response to e.g. inflammatory processes35,36,37. In preclinical studies, GDF-15 had a wider distribution in the developing compared to the adult rat brain. But in the adult brain, GDF-15 was found to be localized in lesioned brain areas, suggesting a direct neuronal anti-inflammatory effect, supplementing other members of the TGF-β superfamily36. As inflammation is known to be strongly associated with and influenced by AF9,38,39, it may serve as a potential treatment target to lower the risk of cognitive decline40. Supporting a role of inflammation, we identified ESM-1 as an important individual biomarker for cognitive decline, which was also selected in the multivariate model along the other inflammatory biomarkers hs-CRP and IGFBP-7. ESM-1 is an endothelial cell-specific molecule, regulated by cytokines, which has been found to be elevated in cardiovascular and cancer patient populations and which is also expressed in human neurons41,42,43,44. More specifically immunoreactive ESM-1 was visualized in the brain in a global blood vessel pattern including the hippocampus in a murine model45.

As a marker of direct neuro-axonal damage, we have found a high discriminatory performance for cognitive decline by NfL. Neurofilaments are structural scaffolding proteins, that are only expressed in neurons46, and it is assumed that they are important for growth and stability of axons for high-velocity nerve conduction47,48. Besides their role as a structural axonal molecule, neurofilaments interact with other proteins and organelles including mitochondria, molecular motors, brain spectrin and proteases49. Any axonal damage leads to releases of neurofilaments into the cerebrospinal fluid and peripheral blood. Increases in serum NfL may therefore identify brain damage at a subclinical stage and predict future brain volume loss in the general population, especially in persons > 60 years of age30. Data on NfL and cognitive decline in patients with AF is scarce. In our AF population, increased NfL levels may indicate subclinical ischemic injuries50,51, but may also be driven by prevalent comorbidities like renal impairment or cardiac disease, supported by our finding of the high individual discriminatory performance of Cystatin C and hs-TnT, and the selection of FGF23 in the multivariate model.

Besides GDF-15, ESM-1 and NfL, GFAP and ALAT were both selected in the less penalized LASSO analysis and the multivariate regression model. GFAP is a key cytoskeletal component and cerebral inflammatory marker, best studied in Alzheimer’s disease as an early risk marker52. Its increase is associated with lower white matter volume in temporal and parietal areas29. Lower ALAT levels have been associated with increased amyloid-β deposition, reduced brain glucose metabolism, greater brain atrophy and low cognition in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative cohort study and with a higher risk of dementia in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study53,54. Reduced ALAT levels may disturb neuronal energy homeostasis and alter glutamate levels, which is a major excitatory neurotransmitter55.

Strengths of our study include the large, well-defined population and strict criteria for cognitive decline over time. The following limitations need be considered: The observational and exploratory study design does not allow to draw causal interferences. The incidence of cognitive decline might be underestimated due to a survival and attrition bias. Patients with severe cognitive dysfunction or disabling comorbidities might not have been able to attend our follow-up visits, limiting the generalizability of our findings to these patient populations. Biomarkers were measured at enrolment only. We could therefore not assess changes in biomarker levels and their relation with cognitive decline. Generalizability of our findings is currently unclear as no external validation was performed. Ideally our investigated biomarkers are investigated in other large patient populations with AF.

In conclusion, in a large AF population, 6.5% developed cognitive decline over 4 years despite a high rate of anticoagulation. Besides ischemic mechanisms, our biomarker analyses indicate that inflammation, neuronal damage, and increased amyloid-beta may be important non-ischemic mechanisms for cognitive decline in AF patients.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Kalantarian, S., Stern, T. A., Mansour, M. & Ruskin, J. N. Cognitive impairment associated with atrial fibrillation: A meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 158, 338–346 (2013).

Chen, L. Y. et al. Persistent but not paroxysmal atrial fibrillation is independently associated with lower cognitive function: ARIC study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 67, 1379–1380 (2016).

Krijthe, B. P. et al. Projections on the number of individuals with atrial fibrillation in the European Union, from 2000 to 2060. Eur. Heart J. 34, 2746–2751 (2013).

Chugh, S. S. et al. Worldwide epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: A Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Circulation 129, 837–847 (2014).

Conen, D. et al. Relationships of overt and silent brain lesions with cognitive function in patients with atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 73, 989–999 (2019).

Kühne, M. et al. Silent brain infarcts impact on cognitive function in atrial fibrillation. Eur. Heart J. 43, 2127–2135 (2022).

Krisai, P. et al. Biomarkers, clinical variables, and the CHA2DS2-VASc score to detect silent brain infarcts in atrial fibrillation patients. J. Stroke 23, 449–452 (2021).

De Marchis, G. M. et al. Biomarker, imaging, and clinical factors associated with overt and covert stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. Stroke https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.123.043302 (2023).

Conen, D. et al. A multimarker approach to assess the influence of inflammation on the incidence of atrial fibrillation in women. Eur. Heart J. 31, 1730–1736 (2010).

Conen, D. et al. Design of the Swiss Atrial Fibrillation Cohort Study (Swiss-AF): Structural brain damage and cognitive decline among patients with atrial fibrillation. Swiss Med. Wkly. 147, w14467 (2017).

Kirchhof, P. et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur. Heart J. 37, 2893–2962 (2016).

Lip, G. Y. H., Patel, J. V., Hughes, E. & Hart, R. G. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein and soluble CD40 ligand as indices of inflammation and platelet activation in 880 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: Relationship to stroke risk factors, stroke risk stratification schema, and prognosis. Stroke 38, 1229–1237 (2007).

Sharma, A. et al. Use of biomarkers to predict specific causes of death in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation 138, 1666–1676 (2018).

Conway, D. S. G., Buggins, P., Hughes, E. & Lip, G. Y. H. Relationship of interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein to the prothrombotic state in chronic atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 43, 2075–2082 (2004).

Cheung, A. et al. Cancer antigen-125 and risk of atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Asia 10, e010970 (2018).

Hijazi, Z. et al. The ABC (age, biomarkers, clinical history) stroke risk score: A biomarker-based risk score for predicting stroke in atrial fibrillation. Eur. Heart J. 37, 1582–1590 (2016).

Wunderlich, M. T. et al. Release of brain-type and heart-type fatty acid-binding proteins in serum after acute ischaemic stroke. J. Neurol. 252, 718–724 (2005).

Januzzi, J. L. et al. IGFBP7 (insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-7) and neprilysin inhibition in patients with heart failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 11, e005133 (2018).

Hennings, E. et al. Bone morphogenetic protein 10-A novel biomarker to predict adverse outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 12, e028255 (2023).

Beck, H., Acker, T., Wiessner, C., Allegrini, P. R. & Plate, K. H. Expression of angiopoietin-1, angiopoietin-2, and tie receptors after middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. Am. J. Pathol. 157, 1473–1483 (2000).

Rocha, S. F. et al. Esm1 modulates endothelial tip cell behavior and vascular permeability by enhancing VEGF bioavailability. Circ. Res. 115, 581–590 (2014).

Hohnloser, S. H. et al. Efficacy of apixaban when compared with warfarin in relation to renal function in patients with atrial fibrillation: Insights from the ARISTOTLE trial. Eur. Heart J. 33, 2821–2830 (2012).

Eslami-Amirabadi, M. & Sajjadi, S. A. The relation between thyroid dysregulation and impaired cognition/behaviour: An integrative review. J. Neuroendocrinol. 33, e12948 (2021).

Jabbar, A. et al. Thyroid hormones and cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 14, 39–55 (2017).

Krisai, P. et al. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation in hyperthyroid patients. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 14, e010200 (2021).

Kang, S. H. et al. Distinct effects of cholesterol profile components on amyloid and vascular burdens. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 15, 197 (2023).

Hendriks, S. et al. Risk factors for young-onset dementia in the UK biobank. JAMA Neurol. 81, 134–142 (2024).

Ellison, J. A. et al. Osteopontin and its integrin receptor alpha(v)beta3 are upregulated during formation of the glial scar after focal stroke. Stroke 29, 1698–1706 (1998) (discussion 1707).

Asken, B. M. et al. Lower white matter volume and worse executive functioning reflected in higher levels of plasma GFAP among older adults with and without cognitive impairment. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. JINS 28, 588–599 (2022).

Khalil, M. et al. Serum neurofilament light levels in normal aging and their association with morphologic brain changes. Nat. Commun. 11, 812 (2020).

Disanto, G. et al. Serum Neurofilament light: A biomarker of neuronal damage in multiple sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 81, 857–870 (2017).

Nasreddine, Z. S. et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 53, 695–699 (2005).

Marzona, I. et al. Increased risk of cognitive and functional decline in patients with atrial fibrillation: Results of the ONTARGET and TRANSCEND studies. CMAJ 184, E329–E336 (2012).

Moffitt, P., Lane, D. A., Park, H., O’Connell, J. & Quinn, T. J. Thromboprophylaxis in atrial fibrillation and association with cognitive decline: Systematic review. Age Ageing 45, 767–775 (2016).

Kempf, T. et al. GDF-15 is an inhibitor of leukocyte integrin activation required for survival after myocardial infarction in mice. Nat. Med. 17, 581–588 (2011).

Schober, A. et al. Expression of growth differentiation factor-15/ macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 (GDF-15/MIC-1) in the perinatal, adult, and injured rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 439, 32–45 (2001).

Lars, W. et al. Growth differentiation factor 15, a marker of oxidative stress and inflammation, for risk assessment in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation 130, 1847–1858 (2014).

Van Wagoner, D. R. & Chung, M. K. Inflammation, inflammasome activation, and atrial fibrillation. Circulation 138, 2243–2246 (2018).

Benz, A. P. et al. Biomarkers of inflammation and risk of hospitalization for heart failure in patients with atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 10, e019168 (2021).

Krisai, P. et al. Canakinumab after electrical cardioversion in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation: A pilot randomized trial. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 13, e008197 (2020).

Lassalle, P. et al. ESM-1 is a novel human endothelial cell-specific molecule expressed in lung and regulated by cytokines. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 20458–20464 (1996).

Balta, S. et al. Endocan–a novel inflammatory indicator in newly diagnosed patients with hypertension: A pilot study. Angiology 65, 773–777 (2014).

Zhang, H. et al. Targeting endothelial cell-specific molecule 1 protein in cancer: A promising therapeutic approach. Front. Oncol. 11, 687120 (2021).

Zhang, S. M. et al. Expression and distribution of endocan in human tissues. Biotech. Histochem. Off. Publ. Biol. Stain Comm. 87, 172–178 (2012).

Frahm, K. A., Nash, C. P. & Tobet, S. A. Endocan immunoreactivity in the mouse brain: Method for identifying nonfunctional blood vessels. J. Immunol. Methods 398–399, 27–32 (2013).

Khalil, M. et al. Neurofilaments as biomarkers in neurological disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 14, 577–589 (2018).

Barry, D. M. et al. Expansion of neurofilament medium C terminus increases axonal diameter independent of increases in conduction velocity or myelin thickness. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 32, 6209–6219 (2012).

Rao, M. V. et al. The neurofilament middle molecular mass subunit carboxyl-terminal tail domains is essential for the radial growth and cytoskeletal architecture of axons but not for regulating neurofilament transport rate. J. Cell Biol. 163, 1021–1031 (2003).

Yuan, A., Rao, M. V., Veeranna, A. & Nixon, R. A. Neurofilaments and neurofilament proteins in health and disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 9, a018309 (2017).

Tiedt, S. et al. Serum neurofilament light: A biomarker of neuroaxonal injury after ischemic stroke. Neurology 91, e1338–e1347 (2018).

Polymeris, A. A. et al. Serum neurofilament light in atrial fibrillation: Clinical, neuroimaging and cognitive correlates. Brain Commun. 2, fcaa166 (2020).

Elahi, F. M. et al. Plasma biomarkers of astrocytic and neuronal dysfunction in early- and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. J. Alzheimers Assoc. 16, 681–695 (2020).

Nho, K. et al. Association of altered liver enzymes with alzheimer disease diagnosis, cognition, neuroimaging measures, and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e197978 (2019).

Lu, Y. et al. Low liver enzymes and risk of dementia. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD 79, 1775–1784 (2021).

Reis, H. J. et al. Neuro-transmitters in the central nervous system & their implication in learning and memory processes. Curr. Med. Chem. 16, 796–840 (2009).

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

The Swiss‐AF study is supported by grants of the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant Numbers 33CS30_148474, 33CS30_177520, 32473B_176178, and 32003B_197524), the Swiss Heart Foundation, the Foundation for Cardiovascular Research Basel (FCVR), and the University of Basel.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

P.K. was responsible for Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft, Formal analysis. M.E. was responsible for Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft, Formal analysis. M.C. was responsible for Writing—Review & Editing, Formal analysis. N.R. was responsible for Writing—Review & Editing. P.C. was responsible for Writing—Review & Editing. S.A. was responsible for Writing—Review & Editing, Project administration. S.B. was responsible for Writing—Review & Editing. V.R. was responsible for Writing—Review & Editing. R.K. was responsible for Writing—Review & Editing. G.M. was responsible for Writing—Review & Editing. E.R. was responsible for Writing—Review & Editing. J.H.B. was responsible for Writing—Review & Editing. A.M. was responsible for Writing—Review & Editing. T.R. was responsible for Writing—Review & Editing. D.C. was responsible for Writing—Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. S.O. was responsible for Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. LHB was responsible for Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. M.K. was responsible for Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Andreas S. Müller received fellowship and training support from Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Abbott/St. Jude Medical, and Biosense Webster. Speaker honoraria from Biosense Webster, Medtronic, Abbott/St. Jude Medical, AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Biotronik, MicroPort, Novartis. Consultant for Biosense Webster, Medtronic, Abbott/St. Jude Medcal, and Biotronik (all outside of the current work). David Conen received consulting fees from Roche Diagnostics, and speaker fees from Servier and BMS/Pfizer, all outside of the current work. Giorgio Moschovitis received advisory board or speaker’s fees from Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Gebro Pharma, Novartis and Vifor, all outside of the submitted work. Jürg H. Beer reports grant support from the Swiss National Foundation of Science, The Swiss Heart Foundation and the Stiftung Kardio; grant support, speakers- and consultation fees to the institution from Bayer, Sanofi and Daichii Sankyo. Leo H. Bonati reports personal fees and nonfinancial support from Amgen, grants from AstraZeneca, personal fees and nonfinancial support from Bayer, personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, personal fees from Claret Medical, grants from Swiss National Science Foundation, grants from University of Basel, grants from Swiss Heart Foundation, outside the submitted work. Michael Kühne reports grants from Bayer, grants from BMS, grants from Boston Scientific, grants from Daiichi Sankyo, grants from Pfizer, personal fees from Abbott, personal fees from Boston Scientific, personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo. Philipp Krisai reports speaker fees from BMS/Pfizer and research grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, Swiss Heart Foundation, Foundation for Cardiovascular Research Basel, Machaon Foundation. Richard Kobza receives institutional grants from Abbott, Biosense-Webster, Boston-Scientific, Biotronik, Medtronic and Sis-Medical. Stefan Osswald Research grant from Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) for Swiss AF Cohort study (33CS30_18474/1&2). Research grant from Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) for Swiss AF Control study (324730_192394/1). Research grants from Swiss Heart Foundation (SHS). Research grants from Foundation for CardioVascular Research Basel (SKFB). Research grants from Roche. Educational and Speaker Office grants from Roche, Bayer, Novartis, Sanofi AstraZeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo, Pfizer. Tobias Reichlin has received research grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Swiss Heart Foundation, the European Union [Eurostars 9799 – ALVALE), and the Cardiovascular Research Foundation Basel, all for work outside the submitted study. He has received speaker/consulting honoraria or travel support from Abbott/SJM, Astra Zeneca, Brahms, Bayer, Biosense-Webster, Biotronik, Boston-Scientific, Daiichi Sankyo, Medtronic, Pfizer-BMS, and Roche, all for work outside the submitted study. He has received support for his institution’s fellowship program from Abbott/SJM, Biosense-Webster, Biotronik, Boston-Scientific, and Medtronic, for work outside the submitted study. Stefanie Aeschbacher received speaker fee from Roche Diagnostics.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Krisai, P., Eberl, M., Coslovsky, M. et al. Biomarker and cognitive decline in atrial fibrillation: a prospective cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 12921 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89800-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89800-9