Abstract

Predation plays a crucial role in community structure and population dynamics, influencing the evolution of various groups. Lizards occupy a central position in predator–prey networks, with some species engaging in saurophagy—where they act as both predator and prey. Here, we investigated saurophagy among the South American lizards, to uncover its biotic and abiotic drivers. We gathered 127 records from the literature, documenting 47 predator species from nine lizard families. Lizards of the family Tropiduridae emerged as both the most frequent predator (39.6%) and the most common prey (26%). Interspecific predation accounted for 63% of cases, while 37% involved cannibalism, primarily targeting juveniles. GLM analyses revealed a positive relationship between predator and prey size. ANOVA did not detect differences in consumption proportional to body size among lizard families. Most records (84%) were in open habitats, particularly the Caatinga and Galápagos. A structural equation model identified isothermality (β = − 0.43), evapotranspiration (β = 0.49), and longitude (β = 0.43) as significant predictors of saurophagy. A random forest model (82% accuracy) highlighted predator family, prey size, and habitat as key decision factors. This study demonstrates the frequent, non-random occurrence of saurophagy in South American lizard assemblages, contributing valuable insights into predator–prey relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Predation plays a crucial role in ecosystem dynamics, functioning as a population regulation mechanism that contributes to maintaining ecological balance. This interaction is fundamental for the structuring of biological communities, as controlling prey numbers prevents overpopulation and, consequently, resource depletion1. Predation can also promote ecological diversity by influencing species distribution and abundance, inducing selective pressures that drive species evolution and adaptation2,3. Investigating predator–prey relationships is an important component of ecosystem dynamic studies because it can identify factors that shape and structure communities4,5,6.

The risk of predation can be influenced by various factors, including those related to environmental conditions7. Certain aspects, such as marked seasonality, can induce different types of microhabitats and landscapes8. For instance, during the dry season in seasonal dry forests, vegetation cover is lost, which often serves as shelter for prey, affecting the use of shelters and, consequently, the risk of predation9. In addition, the reduced availability of food items and the decrease in water in the environment can lead to changes in the food consumed and different predation behaviors compared to those observed in more abundant scenarios10,11. Some organisms, for example, adopt generalist and opportunistic feeding habits as a way to expand the possibilities of utilizing available resources12.

In this context of water and food scarcity, the ability to explore a wide range of food sources offers an adaptive advantage to organisms. Dietary diversity enables more efficient access to nutrients and energy, reducing the effort required to find food and lowering exposure to potential predators (see13). Additionally, generalist feeding helps reduce competition for limited resources, as organisms do not rely on a single type of food. In contrast, specialists may become more vulnerable when environmental changes occur, as their food sources may decrease or disappear14. Therefore, feeding strategies serve as an adaptive response to both biotic challenges, such as predation and competition, and abiotic ones, such as the scarcity of natural resources15,16,17,18,19.

Among the many feeding strategies observed in lizards is the behavior known as saurophagy, which involves the attack and consumption of other lizards, be they individuals of different species or the same species, in both competitive and non-competitive contexts2,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. Invertebrates usually compose almost the entire diet of most lizard species28, but saurophagy was suggested to be one of the mortality causes in sympatric lizard populations29. Squamates, including lizards, are well-known to feed on other squamates30. However, the factors driving the evolution of saurophagy in squamates are poorly understood.

South America exhibits remarkable landscape heterogeneity, ranging from dense tropical rainforests to arid deserts, the grasslands and savannas of the Cerrado and Pampas, to the mountains of the Andes31,32. This environmental complexity results in a wide variety of habitats and ecological conditions capable of influencing the distribution, abundance, and interactions of species throughout their ranges33. This influence is particularly important for ectothermic animals, such as lizards, which rely on environmental conditions to regulate their body temperatures and develop their daily activity34,35. Tropical forests, with their warm and humid climates, support immense biodiversity and, consequently, higher productivity, while drier biomes, such as the Chaco and Caatinga, pose more complex physiological challenges for species36,37. These challenges arise from a seasonal climate regime, with low and restricted rainfall occurring over just a few months of the year and frequent temperature changes8, which in turn lead to reduced water and food availability38,39,40. Such conditions could promote formerly rare behaviors, especially in more environmentally sensitive organisms such as lizards.

The first official record of saurophagy in South American lizards was published 32 years ago (see41). Since then, reports of this behavior have increased considerably in this region, with occurrences documented in various lizard families, such as Gekkonidae, Gymnophthalmidae, Liolaemidae, Phyllodactylidae, Scincidae, Teiidae, and Tropiduridae42. Despite the many reports of saurophagy in South America, no effort has yet been made to compile such data in search of occurrence patterns and their causes. Thus, we remain uncertain as to whether and how abiotic and biotic factors influence the occurrence patterns of this behavior. Herein, we investigate saurophagy in South America by (1) uncovering biological and spatial occurrence patterns in its occurrence, (2) testing for any climatic contribution to the frequency of saurophagy, and (3) identifying key factors influencing predator decision-making.

Results

Families, prey age and type of interaction

We gathered 127 records of saurophagy from literature, across 47 predator species belonging to nine families: Diploglossidae, Gekkonidae, Gymnophthalmidae, Leiosauridae, Liolaemidae, Phyllodactylidae, Scincidae, Teiidae, and Tropiduridae. Tropidurids acted as predators in 62 records (49%), followed by Teiidae with 26 records (20%), Leiosauridae, Scincidae, and Liolaemidae with nine records each (7%), Gekkonidae six records (5%), Phyllodactylidae three records (2%), Gymnophthalmidae two records (2%), and Diploglossidae with one record (1%) (Fig. 1a). The family Tropiduridae was also the most representated in terms of number of predator species in saurophagy records (32%; 15 species) (Fig. 1c). A total of 61 lizard species were recorded as prey items, belonging to 11 families: Tropiduridae (26%; n = 33), Teiidae (16%; n = 21), Liolaemidae (15%; n = 20), Gekkonidae (13%; n = 16), Scincidae (10; n = 13), Gymnophthalmidae (7%; n = 9), Phyllodactylidae (6%; n = 8), Sphaerodactylidae (3%; n = 3), Anolidae (2%; n = 2), Leiosauridae and Diploglossidae (1%; n = 1) (Fig. 1b,d).

Number and relative frequency (percentage) of records of saurophagy by lizard families (a,b) and number of species by family involved in records of saurophagy (c,d) as predator (a,c) or prey (b,d) in South America. A total of 47 species were recorded as predators and 61 species were recorded as prey items.

The number of nodes in the trophic network, representing distinct lizard families or groups, was 40, connected by 49 edges, which represent the feeding interactions between them. The modularity of the network was 0.451. Among the lizard families, Tropiduridae exhibited the highest number of interactions (39.6%; 19 links), followed by Teiidae (29.2%; 14 links), Scincidae (12.5%; 6 links), Leiosauridae (6.2%; 3 links), Gymnophthalmidae (4.2%; 2 links), and several other families (Diploglossidae, Gekkonidae, Liolaemidae, and Phyllodactylidae) with a single interaction each (2.1%; 1 link per family) (Fig. 2).

Trophic network of each family and which genera they interact with. The thickness of the lines represents the number of records for each specific family-genus interaction (interaction force). Colors represent each family. Figure produced using Gephi (http://gephi.org).

Among the records, 63% (n = 80) were interspecific (predation) interactions and 37% (n = 47) were intraspecific (cannibalism) (Supplementary Fig. S5a). The family Tropiduridae had the highest number of cannibalism records (51%; n = 24), followed by Liolaemidae, Gekkonidae, and Teiidae (13%; n = 6), Scincidae (4%; n = 2), and Leiosauridae, Diploglossidae, and Gymnophthalmidae (2%; n = 1 each) (Supplementary Fig. S5b). Juvenile lizards were prey in 53% (n = 38) of predation records and 88% (n = 38) of cannibalism records (Supplementary Fig. S5c,d).

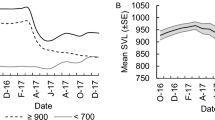

Relationship and proportion of predator and prey body size

Predatory lizards had a mean size (SVL) of 86.41 mm, median of 81.15 mm, maximum size of 250 mm, and minimum of 35 mm. While prey lizards had a mean of 38.56 mm, median of 33.40 mm, maximum of 110 mm, and minimum of 5.70 mm. The general linear regression (Table 1) showed a positive relationship between predator and prey body sizes (n = 68, y = 43 + 1.1x, r2 = 0.58, p ≤ 0.001; Fig. 3a), with larger predators capturing larger prey.

The average proportional consumption was 46% of the predator’s body size, with a median of 46%, a maximum of 69%, and a minimum of 0.7% (Fig. 3b). The ANOVA test indicated that there is no significant difference among families in the variance of consumption proportional to predator body size (F = 1.454; p = 0.194).

Environmental and geographic correlates of saurophagy occurrence

Of 127 saurophagy records, 107 (84%) occurred in open formations and 20 (16%) in forest formations (Supplementary Table S1) (Fig. 4a,b). A heatmap based on kernel density estimation indicated that the Caatinga and Fernando de Noronha Archipelago of NE Brazil, the coastal sand dunes of SE Brazil, the Mediterranean vegetation between Chile and Argentina, and the insular xeric scrub of the Galápagos, are where saurophagy is more likely to occur (Fig. 4c).

Records of saurophagy in open and forest phytophysiongnomies in South America (a), number and percentage of records in each type of formation (b), and heatmap of Kernel density estimation for saurophagy records (c). Both maps in the figure were produced using Qgis (as described in the in Methods section).

The SEM’s model evaluation index indicated that the model was appropriate (comparative fit index; CFI = 0.986; RMSEA = 0.072; SRMR = 0.065). In this model, evapotranspiration (β = 0.49; p = 0.02), Bio3 (isothermality; β = − 0.43; p = 0.05), and longitude (β = 0.43; p = 0.001) were the environmental and geographic predictors significantly and directly related to the frequency of saurophagy (Fig. 5: Supplementary Fig. S6).

Structural Equation Model (SEM) summarization of geographic and bioclimatic variable effects on the variation of the frequency of saurophagy records in South America. Lat = latitude; Lon = longitude; Bio3 = isothermality; Bio5 = max temperature of warmest month; Bio15 = precipitation seasonality; Bio18 = precipitation of warmest quarter; ET = evapotranspiration; PP = primary productivity. The arrow thickness represents the effect size of predictor variables. Solid arrows represent significant effects (values in bold) and dotted arrows represent no significant effect. Red arrows represent negative associations and blue arrows represent positive associations. β = standardized regression coefficients. Saurophagy illustration by: Lucas Rosado.

Predictors of predator decision-making

The RF model showed an error rate of 19% for the training set and was able to predict/classify the type of interaction with an accuracy of 82%, sensitivity of 83%, and specificity of 81%. The most important predictors were predator family, followed by prey size and predator size (according to MDA) and predator family, followed by prey habitat use and prey size (according to Gini) (Fig. 6). The Shapley values to these predictors were: predator family (phi = 0.31; var.phi = 0.26), prey habitat use (phi = 0.15; var.phi = 0.17), prey size (phi = 0.06; var.phi = 0.06), predator size (phi = 0.02; var.phi = 0.02) (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Discussion

We found that saurophagy occurs in nine of 14 families of South American lizards (see43,44,45,46,47), but that it is more common in a few of them. This behavior was not recorded in Iguanidae, Hoplocercidae, Polychrotidae, Sphaerodactylidae, and Anguidae. Juveniles and non-conspecifics are prey in most cases. We also found a positive relationship between predator and prey body size. This behavior was more common in open and dry biomes and was partially explained by instability in temperature (low isothermality) and high evapotranspiration. We also demonstrated that, although saurophagy is an opportunistic behavior, predators seem to not choose prey non-randomly, being probably influenced by predator family characteristics, prey body size, and prey habitat use.

Linear regression demonstrated a positive relationship between predator and prey body sizes. In lizards, this relationship could be explained by bite force capacity, which is influenced by the relationship between body and head size48,49. Although large species eat larger prey, we did not find significant differences in predator–prey body size proportion between families (on average, predators invested in prey with 46% of their body size). Our findings on this matter show a trend opposite to that of anurophagy. Recently, it was demonstrated that smaller frog species can consume proportionally larger frogs6. Unlike amphibians, lizards have higher movement and displacement rates, as they possess physiological adaptations that help prevent excessive dehydration50,51, which may result in more opportunities to find food items that are not too large to hinder digestion, yet not too small to be insufficiently energetic. Additionally, the presence of a tail may further limit predation in larger lizards, as it increases the overall size of the prey, making it harder to consume it whole. Moreover, the proportional gape size relative to body size in lizards may be smaller compared to generalist frogs, where prey consumption can be closer to the predator’s own body size52. This may restrict lizards to consuming prey that are proportionally smaller relative to their body size. Future studies are needed to clarify these issues and to better understand how body size influences proportional prey consumption in lizards.

We found that most of the saurophagy records in South America have been made in open phytophysiognomies, and the frequency of this behavior is influenced by isothermality longitudinally. Isothermality is a highly important bioclimatic variable for ectothermic animals, being partially responsible for the distribution patterns of many reptiles53,54,55. In general, the stability of environmental temperature promotes more predictable activity patterns and more suitable conditions for growing and developing in ectothermic species56,57,58, especially because stable environments provide more stable food availability59,60,61. Here, we observed that isothermality was inversely related to saurophagy occurrence, which could mean that this behavior is more frequent in more unstable environments, especially with respect to night–day temperature oscillations.

Although we did not find significant influence of the variable primary productivity (used as proxy of prey availability62) on the saurophagy occurrence, we found a positive effect of the evapotranspiration longitudinally on this behavior. Open environments tend to be less isothermic and less humid due to their sparse vegetation structure and high evapotranspiration, which results from lower precipitation rates and greater exposure to UV radiation8. In regions where predominate open environments, lizards often experience reduced water availability and lower prey diversity during certain times of the year63, as the reproductive cycles of some arthropods they consume are closely tied to precipitation patterns64. In some snake species, warmer habitats promote increased movement and prolonged activity65, leading to heightened predation pressure66. Despite being phylogenetically closely related to snakes, lizards respond differently to high temperatures by reducing exploratory behavior and seeking refuge in suitable shelters67. As a result, in open environments and under high evapotranspiration, lizards likely focus on prey that is easier to locate, as closely related species that utilize similar landscape features for shelter. In fact, our trophic network demonstrated that most predators prioritized prey from the same family or genus, which are usually syntopic.

The random forest model demonstrated that the predator family was the most important predictor of the predator decision-making. This was expected, since Tropiduridae and Teiidae were the most common families in saurophagy events. Among the families with saurophagy records in the literature, these two are the most abundant in open habitats68,69, where we found most of the saurophagy records. Prey body size was another important predictor of saurophagy, which corroborates our finding that small species and juveniles are the main targets, especially in cannibalism events as we saw by the greater percentage of cases involving juveniles as prey. Juvenile individuals spend more time foraging compared to adults, maximizing energy intake based on their size and prey availability70,71. Consequently, encounter rates with juveniles may be higher since they are more active than adults. Moreover, juveniles have less defense29,72. Another predictor evidenced was prey habitat use, which was already observed in a previous study investigating autotomy as a proxy of predation pressure in snakes and amphisbaenian species in South America and West Africa73. A possible explanation is based on the exposure level of prey to predators according to the substrate structure (see7)—warm habitats are usually more susceptible to predation pressure66, what also corroborates the higher occurrence of saurophagy in open environments.

The genus Tropidurus was the most frequent in our records, especially in terms of cannibalism. The diet of these sit-and-wait predators74 is mainly composed of arthropods and plants10,69,75,76,77,78,79, but also includes vertebrates such as amphibians78,80,81,82, mammals83,84, birds85,86, snakes87,88, and other lizards77,89,90,91,92,93. Tropidurus males often fight each other for territory and females, especially adults and juveniles72,94,95. Cannibalism is also very frequent in this genus2,72,96, perhaps due to their propensity for territorial combat encounters.

Among our saurophagy records, cannibalistic behavior seems to be particularly more common in generalist lizard species97. The high number of cannibalism records indicates that this type of interaction is not only common but also important to the ecology of many species, as it strongly influences population dynamics98, for example, by reducing the number of potential competitors99. Several eco-evolutionary factors result from cannibalism, including population density self-regulation100,101, a reduction in genetic variability within populations102, and increased risk of parasite infections103,104.

We could not account for every possible factor influencing the response variable. For example, one unstudied factor that may influence the spatial pattern of saurophagy is the diversity of lizard species in a given area6. Since areas closer to the Equator have greater diversity, this raises the question: Are areas with greater lizard diversity more prone to occurrences of saurophagy? Future studies are needed to determine whether high diversity within specific groups is a reliable predictor of predator–prey interactions within those same groups. Another factor could be the possible influence of the distribution of urban centers, number of specialists, and local research institutions that drive the publication of such data105. However, we focused on accounting for natural biotic and abiotic predictors independently of human influence. Furthermore, we believe that the distribution of urban centers could not explain the patterns of saurophagy occurrence that we found, as the biggest cities in territory and demography in all South America are in the Southeast region of Brazil (specifically, São Paulo state and city), where we found very few records compared to other regions.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that, despite numerous records, saurophagy remains a rare event in South American lizard assemblages, especially considering the large geographic scale and long sampling period of the present study. However, in open landscapes, this behavior becomes less rare due to higher temperatures, lower precipitation, and increased evapotranspiration rates, which can reduce food availability for most of the year. Key factors influencing predator decision-making include predator family, prey size, and prey habitat use. Our findings highlight potential drivers of saurophagy that can serve as a foundation for hypothesis testing in other regions, contributing to a better understanding of predator–prey interactions and their evolutionary and ecological implications. Given the ongoing climate change and increasing aridification, future studies on lizard social interactions and life history traits could improve predictions of dietary patterns and their deviations. Since climate change can affect invertebrate prey availability40, its potential role in intensifying saurophagy, especially cannibalism, should not be overlooked. Lastly, we emphasize the value of scientific collections, as many of the studies reviewed here were based on specimens from these invaluable resources.

Methods

Information sources and search strategy

We performed an extensive search for saurophagy records in South America until August 2024 in all volumes of Herpetological Review and on the main search platforms: Scopus, Scielo, ResearchGate, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, JSTOR, Directory of Open Access Journals & Articles (DOAJ), ScienceResearch, WorldWideScience, Springer, Science.gov, and Google Scholar. We used an association of 15 terms, in English, Portuguese, and Spanish, to retrieve all the terms listed in a single document and also separated into different documents: lizard or lagarto or lagartija or saurophagy or saurofagia or South America or América do Sul or América del Sur or predation or predação or predación or cannibalism or canibalismo or diet or dieta. We also used the “snowball” method, i.e., searching for records in the references of articles obtained in the research. We did not consider records of undergraduate or master’s dissertations, or theses or abstracts presented in congresses or symposiums. For those publications which reported more than one event, we considered each record separately. We considered predation events recorded in all their phases106,107.

From each record, we collected the following information: both predator and prey species name and body size, prey age, and name and coordinates of the locality (Supplementary Table S1). We completed our dataset with more information about environmental qualitative classification of each locality (macrohabitat). We made a macrohabitat classification of those biomes as “open” areas for those characterized by dry climate (high temperatures and low precipitation rates), and sparse and low vegetation, and “forest” areas for those composed by wet climate and dense vegetation cover. We conducted our macrohabitat classification based on the Dinerstein et al.108 biome classification (Supplementary Table S1). We also added information about the species (predator and prey taxonomic family, predator foraging mode, predator and prey body size, and habitat use type of the prey), syntopy (habitat overlapping in the main microhabitat type used by the predator and prey species), and type of interaction during the recorded event (inter or intraspecific) to our dataset. For qualitative classification of body size, we considered species with snout-vent length ≤ 60 mm as “small”, ≥ 61 and ≤ 200 mm as “medium”, and ≥ 200 as “large” based on the taxonomic literature of the species—the literature we gathered, also species description and ecology papers, uses this categorization when characterizing species or species of the same genus. We also used the literature to classify foraging mode (Supplementary Table S2).

Data analyses

Descriptive analyses and statistic tests

We calculated the number and percentage of records in different categories: predator and prey family, prey age, type of interaction and macrohabitat. To assess patterns of macrohabitat distribution, we plotted all the records gathered in a Qgis map109. After that, we applied the Kernel Density tool to identify hotspots of saurophagy occurrence. To graphically represent the predator–prey relationship among lizard families and genera, we created a trophic network among species and plotted it using the software Gephi110. The structure of such networks can be analyzed using modularity, a metric that quantifies the extent to which the network can be divided into distinct modules or communities. Since modularity identifies clusters where interactions are denser within than between modules, it provides insight into how feeding interactions are distributed among lizard families, helping to determine whether certain families tend to share similar prey types or occupy distinct trophic niches. To assess the effect of body length (SVL) between prey and predators, we performed a generalized linear model (GLM) analysis using discrete data on the snout–vent length of predators and prey available in the literature. Due to the data distribution, a Poisson family GLM with a logarithmic link function was applied. To analyze the difference in the proportional consumption of prey in relation to the predator’s body size (prey SVL/predator SVL), we performed an analysis of variance (ANOVA). We plotted values and calculated the probability density of paired data (predator and prey sizes) using the ‘ggplot2’111, ‘car’112, ‘tydiverse’113, and ‘viridis’114 R packages implemented in R version 3.5.1115.

Abiotic predictors of saurophagy

To investigate possible influence of environmental and geographic features on the occurrence of saurophagy, we mapped all saurophagy records over 59 grid cells with 2° grain throughout South America, including oceanic islands. We used that grain size to create enough variation between the grid cells (each one had between 1 and 9 records) (Supplementary Fig. S3). While creating that grid we also produced a presence-absence matrix using the function ‘lets.presab.points’ from the ‘letsR’ R package116. This matrix contained grid cell identification, centroid geographical coordinates of each grid cell, and the records of each grid cell. We also used the ‘rgdal’117, ‘sp’118, ‘maps’119, and ‘terra’120 R packages in those steps. Using those centroid geographical coordinates, we extracted values of 19 bioclimatic variables (corresponding to the period between 1970 and 2000, 10 min resolution ~ 340 km2 from WorldClim 2.1 (Fick and121) using the ‘raster’122, ‘sp’118, and ‘rgeos’123 R packages and applying the functions ‘extent’, ‘crop’, and ‘extract’.

Those bioclimatic variables represent variations in temperature (Bio1–Bio11) and precipitation (Bio12–Bio19). After that, we eliminated collinearity between the set of bioclimatic variables using the functions ‘colindiag’ and ‘findCorrelation’ from the R packages ‘metan’124 and ‘caret’125, respectively. Hereafter we used only Bio3 (Isothermality), Bio5 (Max Temperature of Warmest Month), Bio15 (Precipitation Seasonality), and Bio18 (Precipitation of Driest Quarter). The first function computes collinearity diagnostics, such as variance inflation factors (VIF), eigenvalues, and condition indices and, the second function, identifies and removes highly correlated variables based on a specified correlation threshold (We defined 0.7), helping to reduce redundancy in predictors and improving model stability.

We also took values from MODIS VI evapotranspiration (MOD16A2: MODIS Global Terrestrial Evapotranspiration 8-Day Global 1 km) and primary productivity (MYD17A2H.061: Aqua Gross Primary Productivity 8-Day Global 500 m) rasters using Qgis. Those rasters were downloaded from Google Earth Engine (https://earthengine.google.com/)126. Then, we created a dataset containing grid cell number and their corresponding latitude, longitude, number of records, and bioclimatic variables (Supplementary Table S4). We used this dataset to perform Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) running the ‘lavaan’ 0.6.16 R package127,128, using the number of records as the response variable and Bio3, Bio5, Bio15, Bio18, evapotranspiration, and primary productivity as predictor variables. These bioclimatic variables and evapotranspiration affect the microclimate and habitat variation at the local scale resulting in physiological consequences for ectotherms, such as body water loss129 and physical performance changes due to dehydration130. The primary productivity could indirectly represent prey availability, affecting ecological interactions in food web dynamics62. With SEM we were able to verify the direct and indirect effects among all variables simultaneously through regression models.

Biotic predictors for the predator decision-making

We built a Random Forest (RF) classifier131,132 to identify important predictors of the predator choice before catching its prey (that is, what predator and prey characteristics are important for an individual to decide whether to prey on a conspecific or an individual of another species). RF produces an ensemble of decision trees from a bootstrap set built from an initial training data set (usually 70% of the observations). Those remaining observations (usually 30%) compose the test group, treated as observations needed to be predicted from the previous final prediction using the training group133. It is a high accuracy method even when applied on small sample sizes with high-dimensional feature spaces, and is also easily parallelizable, thus, it is ideal for use with natural systems134. We used the type of interaction (two classifications: interspecific and cannibalism) as the response (dependent) variable. As predictor (independent) variables, we used eight categorical variables: predator family (considering the possibility of phylogenetic influence), predator foraging mode (the movement rate could affect the attack performance), predator size (large organisms usually require more energy and are also capable to capture more item variety), prey age (juveniles could be easier to capture because of their lower experience in escaping and combat), prey size (small lizards could be easier to capture, hold, swallow, and digest), prey habitat use (some microhabitats could influence the detection and capture of prey by predator), macrohabitat (saurophagy occurrence could be different between open and forest biomes), and syntopy (the predator could more easily capture prey if both share microhabitat).

Although the RF approach does not specifically answer why an individual preys on another lizard (perhaps because the response lies in abiotic factors), it helps us to understand how this decision is made. To apply RF, we first defined the training and test groups and set k-fold cross-validation (method = cv; number = 10) using the function ‘trainControl’. After that, we looked for the best mtry (subset of variables randomly sampled as candidate predictors for splitting at each node of each tree) and ntree (number of trees to be built) to our dataset using the function ‘train’ from the ‘caret’ R package125. We then performed the function ‘randomForest’ from the ‘randomForest’ R package135 using the suggested parameters mtry = 5 and ntree = 1000. Finally, we ranked the importance of each predictor based on the Mean Decrease in Accuracy (MDA)131 and Mean Decrease in Gini (GINI) metrics132 and Shapley values136.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or in the supplementary information files (available in the online version).

References

Pianka, E. R. Niche relations of desert lizards. In Ecology and Evolution of Communities, 292–314 (1975).

Sales, R. F. D., Jorge, J. S., Ribeiro, L. B. & Freire, E. M. X. A case of cannibalism in the territorial lizard Tropidurus hispidus (Squamata: Tropiduridae) in Northeast Brazil. Herpetol. Notes 4, 265–267 (2011).

Taylor, R. J. Predation (Springer, 2013).

Bohannan, B. J. & Lenski, R. E. The relative importance of competition and predation varies with productivity in a model community. Am. Nat. 156, 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1086/303393 (2000).

Pianka, E. R. The structure of lizard communities. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 4, 53–74. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000413 (1973).

Souza, U. F. et al. Frog eat frogs: the relationship among the Neotropical frogs of the genus Leptodactylus and their anuran prey. Food Webs 37, e00326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fooweb.2023.e00326 (2023).

Ferreira, A. S. & Faria, R. G. Predation risk is a function of seasonality rather than habitat complexity in a tropical semiarid forest. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 16670. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96216-8 (2021).

da Silva, J. M. C. et al. (eds) Caatinga: The Largest Tropical Dry Forest Region in South America (Springer, 2018).

Sih, A. To hide or not to hide? Refuge use in a fluctuating environment. Trends Ecol. Evol. 12(10), 375–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(97)87376-4 (1997).

Kolodiuk, M. F., Ribeiro, L. B. & Freire, E. M. X. The effects of seasonality on the foraging behavior of Tropidurus hispidus and Tropidurus semitaeniatus (Squamata: Tropiduridae) living in sympatry in the Caatinga of northeastern Brazil. Zoologia (Curitiba) 26, 581–585. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-46702009000300026 (2009).

Oliveira, P. M. A., Feitosa, J. L. L. & Nunes, P. M. S. Seasonal influence on the feeding patterns of three sympatric Tropidurus lizards (Squamata: Tropiduridae) of the Caatinga, in the Brazilian semi-arid region. S. Am. J. Herpetol. 31(1), 56–64. https://doi.org/10.2994/SAJH-D-21-00043.1 (2024).

Mella, J., Tirado, C., Cortés, A. & Carretero, M. Seasonal variation of prey consumption by Liolaemus barbarae, a highland lizard endemic to Northern Chile. Anim. Biol. 60(4), 413–421. https://doi.org/10.1163/157075610X523288 (2010).

Clavel, J., Julliard, R. & Devictor, V. Declínio mundial de espécies especializadas: Rumo a uma homogeneização funcional global?. Frente. Eco. Meio Ambiente 9, 222–228. https://doi.org/10.1890/080216 (2011).

Le Feuvre, M. C., Dempster, T., Shelley, J. J., Davis, A. M. & Swearer, S. E. Range restriction leads to narrower ecological niches and greater extinction risk in Australian freshwater fish. Biodivers. Conserv. 30(11), 2955–2976. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-021-02229-0 (2021).

Ben-David, M., Flynn, R. W. & Schell, D. M. Annual and seasonal changes in diets of martens: Evidence from stable isotope analysis. Oecologia 111, 280–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420050236 (1997).

Eriksen, E. et al. Diet and trophic structure of fishes in the Barents Sea: Seasonal and spatial variations. Prog. Oceanogr. 197, 102663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2021.102663 (2021).

Hirsch, B. T. Seasonal variation in the diet of ring-tailed coatis (Nasua nasua) in Iguazu, Argentina. J. Mammal. 90(1), 136–143. https://doi.org/10.1644/08-mamm-a-050.1 (2009).

Porter, C. K., Golcher-Benavides, J. & Benkman, C. W. Seasonal patterns of dietary partitioning in vertebrates. Ecol. Lett. 25(11), 2463–2475. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.14100 (2022).

Sydeman, W. J. et al. Climate change, reproductive performance and diet composition of marine birds in the southern California Current system, 1969–1997. Prog. Oceanogr. 49(1–4), 309–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6611(01)00028-3 (2001).

Albuquerque, S. Tropidurus oreadicus (NCN). Cannibalism and prey. Herpetol. Rev. 41, 231–232 (2010).

Araújo, A. F. B. Comportamento alimentar dos lagartos: O caso dos Tropidurus do grupo torquatus da Serra dos Carajás, Pará (Sauria: Iguanidae). An. Etol. 5, 203–234 (1987).

Dias, E. J. R. & Rocha, C. F. D. Tropidurus hygomi (NCN). Juvenile predation. Herpetol. Rev. 35, 398–399 (2004).

Dutra, G. F. Uso de HABITATS, tamanho, Dieta e Locais de Desova de Tropidurus Torquatus (Sauria: Tropiduridae) em Abrolhos, BA. Unpublished Bachelor thesis. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brasil (1996).

Kiefer, M. C. & Sazima, I. Diet of juvenile tegu lizard Tupinambis merianae (Teiidae) in southeastern Brazil. Amphib. Reptilia 23(1), 105–108 (2002).

Kiefer, M. C., Siqueira, C. C., Van Sluys, M. & Rocha, C. F. D. Tropidurus torquatus (Collared Lizard, Calango). Prey. Herpetolol. Rev. 37, 475–476 (2006).

Kohlsdorf, T., Godoy, C. & Navas, C. A. Tropidurus hygomi (NCN). Cannibalism. Herpetol. Rev. 35, 398 (2004).

Robbins, T. R., Schrey, A., McGinley, S. & Jacobs, A. On the incidences of cannibalism in the lizard genus Sceloporus: Updates, hypotheses, and the first case of siblicide. Herpetol. Notes 6, 523–528 (2013).

Pianka, E. R. & Vitt, L. J. Lizards: Windows to the Evolution of Diversity (University of California Press, 2003). https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520234017.001.0001.

Vitt, L. J. Ecological consequences of body size in neonatal and small-bodied lizards in the Neotropics. Herpetol. Monogr. 14, 388–400. https://doi.org/10.2307/1467053 (2000).

Schalk, C. M. & Cove, M. V. Squamates as prey: Predator diversity patterns and predator–prey size relationships. Food Webs 17, e00103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fooweb.2018.e00103 (2018).

Eva, H. D. et al. A land cover map of South America. Glob. Change Biol. 10(5), 731–744. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-8817.2003.00774.x (2004).

Olson, D. M. et al. Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: A new map of life on earth: A new global map of terrestrial ecoregions provides an innovative tool for conserving biodiversity. BioScience 51(11), 933–938. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0933:teotwa]2.0.co;2 (2001).

Mittermeier, R. A. et al. Wilderness and biodiversity conservation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100(18), 10309–10313. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1732458100 (2003).

Abram, P. K., Boivin, G., Moiroux, J. & Brodeur, J. Behavioural effects of temperature on ectothermic animals: Unifying thermal physiology and behavioural plasticity. Biol. Rev. 92, 1859–1876. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12312 (2017).

Wieser, W. Effects of Temperature on Ectothermic Organisms (Springer, 1973). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-65703-0.

Owen-Smith, N. & Goodall, V. Coping with savanna seasonality: Comparative daily activity patterns of African ungulates as revealed by GPS telemetry. J. Zool. 293(3), 181–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/jzo.12132 (2014).

Rozen-Rechels, D. et al. When water interacts with temperature: Ecological and evolutionary implications of thermo-hydroregulation in terrestrial ectotherms. Ecol. Evol. 9(17), 10029–10043. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.5440 (2019).

Capula, M., Chiantini, S., Luiselli, L. & Loy, A. Size and shape in Mediterranean insular lizards: Patterns of variation in Podarcis raffonei, P. sicula and P. wagleriana (Reptilia: Squamata: Lacertidae). Aldrovandia 5, 217–227 (2009).

Taverne, M. et al. Diet variability among insular populations of Podarcis lizards reveals diverse strategies to face resource-limited environments. Ecol. Evol. 9(22), 12408–12420. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.5626 (2019).

Thomas, R. J., Vafidis, J. O. & Medeiros, R. J. Climatic impacts on invertebrates as food for vertebrates. In Global Climate Change and Terrestrial Invertebrates (eds Jones, T. H. & Johnson, S. N.) 295–316 (Wiley, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119070894.ch15.

Rocha, C. F. D. Liolaemus lutzae (Sand Lizard). Cannibalism. Herpetol. Rev. 23(2), 60 (1992).

Rocha, C. F. D. & Siqueira, C. C. Feeding ecology of the lizard Tropidurus oreadicus Rodrigues 1987 (Tropiduridae) at Serra dos Carajás, Pará state, northern Brazil. Braz. J. Biol. 68, 109–113. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842008000100015 (2008).

Ávila, R. W. & Silva, R. J. Checklist of helminths from lizards and amphisbaenians (Reptilia, Squamata) of South America. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 16, 543–572. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-91992010000400005 (2010).

Canavero, A. et al. Conservation status assessment of the amphibians and reptiles of Uruguay. Iheringia Sér. Zool. 100, 05–12. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0073-47212010000100001 (2010).

De Gamboa, M. R. Estados de conservación y lista actualizada de los reptiles nativos de Chile. Bol. Chil. Herpetol. 7, 1–11 (2020).

Guedes, T. B., Entiauspe-Neto, O. M. & Costa, H. C. Lista de répteis do Brasil: Atualização de 2022. Herpetol. Bras. 12(1), 56–161 (2023).

Rivas, G. A. et al. Reptiles of Venezuela: An updated and commented checklist. Zootaxa 3211(1), 1–64. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3211.1.1 (2012).

Herrel, A., Joachim, R., Vanhooydonck, B. & Irschick, D. J. Ecological consequences of ontogenetic changes in head shape and bite performance in the Jamaican lizard Anolis lineatopus. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 89, 443–454. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.2006.00685.x (2006).

Verwaijen, D., Van Damme, R. & Herrel, A. Relationships between head size, bite force, prey handling efficiency and diet in two sympatric lacertid lizards. Funct. Ecol. 16, 842–850. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2435.2002.00696.x (2002).

Camacho, A., Brunes, T. O. & Rodrigues, M. T. Dehydration alters behavioral thermoregulation and the geography of climatic vulnerability in two Amazonian lizards. PLoS ONE 18(11), e0286502. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0286502 (2023).

Weaver, S. J., McIntyre, T., van Rossum, T., Telemeco, R. S. & Taylor, E. N. Hydration and evaporative water loss of lizards change in response to temperature and humidity acclimation. J. Exp. Biol. 226, jeb246459. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.246459 (2023).

Silva, C. M. M., Dalmolin, D. A., Schuck, L. K., Moser, C. F. & Tozetti, A. M. Predator morphology affects prey consumption: Evidence from an anuran population in subtropical wetlands. Herpetol. J. 34, 137–144. https://doi.org/10.33256/34.3.137144 (2024).

Ceron, K. et al. Ecological niche explains the sympatric occurrence of lined ground snakes of the genus Lygophis (Serpentes, Dipsadidae) in the South American dry diagonal. Herpetologica 77, 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1655/Herpetologica-D-20-00056.1 (2021).

Sanchooli, N. Ecological variables determining the presence of lizards in the Sistan region, Eastern Iran. Ecol. Res. 32, 995–999. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11284-017-1514-8 (2017).

Tytar, V., Sobolenko, L., Nekrasova, O. & Mezhzherin, S. Using ecological niche modeling for biodiversity conservation guidance in the western Podillya (Ukraine): Reptiles. Becтник зooлoгии 49(6), 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1515/vzoo-2015-0065 (2015).

Araújo, M. B., Thuiller, W. & Pearson, R. G. Climate warming and the decline of amphibians and reptiles in Europe. J. Biogeogr. 33, 1712–1728. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01482.x (2006).

Schulte, P. M., Healy, T. M. & Fangue, N. A. Thermal performance curves, phenotypic plasticity, and the time scales of temperature exposure. Integr. Comp. Biol. 51, 691–702. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/icr097 (2011).

Telemeco, R. S., Radder, R. S., Baird, T. A. & Shine, R. Thermal effects on reptile reproduction: Adaptation and phenotypic plasticity in a montane lizard. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 100(3), 642–655 (2010).

Adams, S. M., McLean, R. B. & Huffman, M. M. Structuring of a predator population through temperature-mediated effects on prey availability. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 39, 1175–1184. https://doi.org/10.1139/f82-155 (1982).

Madsen, T. & Shine, R. Seasonal migration of predators and prey—A study of pythons and rats in tropical Australia. Ecology 77(1), 149–156. https://doi.org/10.2307/2265663 (1996).

Marniche, F., Exbrayat, J. M., Amroun, M., Herrel, A. & Mamou, R. Seasonal variation in diet and prey availability in the wall lizard Podarcis vaucheri (Boulenger, 1905) from the Djurdjura Mountains, northern Algeria. Afr. J. Herpetol. 68, 18–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/21564574.2018.1509138 (2019).

Brown, C. J. et al. Effects of climate-driven primary production change on marine food webs: Implications for fisheries and conservation. Glob. Change Biol. 16, 1194–1212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02046.x (2010).

McLaughlin, J. F., Hellmann, J. J., Boggs, C. L. & Ehrlich, P. R. Climate change hastens population extinctions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99, 6070–6074. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.052131199 (2002).

Araújo, C. S. et al. Seasonal variations in scorpion activities (Arachnida: Scorpiones) in an area of Caatinga vegetation in northeastern Brazil. Zoologia (Curitiba) 27, 372–376. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-46702010000300008 (2010).

Eskew, E. A. & Todd, B. D. Too cold, too wet, too bright, or just right? Environmental predictors of snake movement and activity. Copeia 105(3), 584–591. https://doi.org/10.1643/CH-16-513 (2017).

Roslin, T. et al. Higher predation risk for insect prey at low latitudes and elevations. Science 356, 742–744. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaj1631 (2017).

Sannolo, M. & Carretero, M. A. Dehydration constrains thermoregulation and space use in lizards. PLoS One 14, e0220384. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220384 (2019).

Sartorius, S. S., Vitt, L. J. & Colli, G. R. Use of naturally and anthropogenically disturbed habitats in Amazonian rainforest by Ameiva ameiva. Biol. Conserv. 90, 91–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(99)00019-1 (1999).

Vitt, L. J. Ecology of isolated open-formation Tropidurus (Reptilia: Tropiduridae) in Amazonian lowland rain forest. Can. J. Zool. 71, 2370–2390. https://doi.org/10.1139/z93-333 (1993).

Paulissen, M. A. Optimal foraging and intraspecific diet differences in the lizard Cnemidophorus sexlineatus. Oecologia 71, 439–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00378719 (1987).

Taylor, J. A. Food and foraging behaviour of the lizard, Ctenotus taeniolatus. Aust. J. Ecol. 11(1), 49–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9993.1986.tb00916.x (1986).

Siqueira, C. C. & Rocha, C. F. D. Predation by lizards as a mortality source for juvenile lizards in Brazil. S. Am. J. Herpetol. 3, 82–87. https://doi.org/10.2994/1808-9798(2008)3[82:PBLAAM]2.0.CO;2 (2008).

Moura, M. R. et al. Unwrapping broken tails: Biological and environmental correlates of predation pressure in limbless reptiles. J. Anim. Ecol. 92, 324–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13793 (2023).

Schoener, T. W. Theory of feeding strategies. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2, 369–404. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.02.110171.002101 (1971).

Cooper, W. E. Jr. & Vitt, L. J. Distribution, extent, and evolution of plant consumption by lizards. J. Zool. 257, 487–517. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0952836902001085 (2002).

Ferreira, A. S., de Oliveira Silva, A., da Conceição, B. M. & Faria, R. G. The diet of six species of lizards in an area of Caatinga, Brazil. Herpetol. J. 27(2), 151–160 (2017).

Oliveira, P. M. A., Navas, C. A. & SalesNunes, P. M. Diet composition and trophic niche overlap of Ameivula ocellifera Spix 1825 (Squamata: Teiidae) and Tropidurus cocorobensis Rodrigues 1987 (Squamata: Tropiduridae), sympatric species with different foraging modes, in Caatinga. Herpetol. J. 32, 4. https://doi.org/10.33256/32.4.190197 (2022).

Ribeiro, L. B. & Freire, E. M. X. Thermal ecology and thermoregulatory behavior of Tropidurus hispidus and Tropidurus semitaeniatus in a caatinga area of northeastern Brazil. Herpetol. J. 20, 201–208 (2010).

Van Sluys, M. Food habits of the lizard Tropidurus itambere (Tropiduridae) in southeastern Brazil. J. Herpetol. 27, 347–351. https://doi.org/10.2307/1565162 (1993).

Costa, J. C. L., Manzani, P. R., Brito, M. P. L. & Maciel, A. O. Tropidurus hispidus (Calango). Prey. Herpetol. Rev. 41, 87 (2010).

Mendes, R. B. Tropidurus hispidus (Neotropical Ground Lizard). Diet and prey capture. Herpetol. Rev. 48, 201–202 (2017).

Vitt, L. J., Zani, P. A. & Caldwell, J. P. Behavioural ecology of Tropidurus hispidus on isolated rock outcrops in Amazonia. J. Trop. Ecol. 12, 81–101. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467400009329 (1996).

Gasparini, J. L. & Peloso, P. L. Tropidurus torquatus (Brazilian Collared Lizard). Diet. Herpetol. Rev. 38, 464 (2007).

Virginio, F., Jorge, J. S., Maciel, T. T. & Barbosa, B. C. Attempt to opportunistic consumption of Mus musculus Linnaeus, 1758 (Rodentia: Muridae) by Tropidurus hispidus (Spix, 1825) (Squamata: Tropiduridae) in an urban area in Brazil. Rev. Bras. Zoociências 18, 207–210 (2017).

Fernandes, I. Y., Marinho, I. & Viana, P. F. Tropidurus hispidus (Neotropical Lava Lizard). Diet. Herpetol. Rev. 51, 135 (2020).

Guedes, T. B., Miranda, F. H. B., Menezes, L. M. N., Pichorim, M. & Ribeiro, L. B. Avian predation attempts by Tropidurus hispidus (Spix, 1825) (Reptilia, Squamata, Tropiduridae). Herpetol. Notes 10, 45–47 (2017).

Santos, A. S., Meneses, A. S. O., Horta, G. F., Rodrigues, P. G. A. & Brandão, R. A. Predation attempt of Tropidurus torquatus (Squamata, Tropiduridae) on Phalotris matogrossensis (Serpentes, Dipsadidae). Herpetol. Notes 10, 341–343 (2017).

Souza, U. F., de Oliveira Nogueira, C. H., Dubeux, M. J. M., Santos, S. M. & Tinôco, M. S. Erythrolamprus miliaris (Linnaeus, 1758) (Squamata: Dipsadidae) a new prey item of Tropidurus torquatus (Wied-Neuwied, 1820) (Squamata: Tropiduridae) in Southeastern Brazil. Oecol. Aust. 25(4), 904–908. https://doi.org/10.4257/oeco.2021.2504.12 (2021).

Dubeux, M. J. M., Oliveira, P. M. A., Mello, A. V. A., Matias, I. T. A. & Santos, W. N. S. Phyllopezus pollicaris (Rock Gecko). Predation. Herpetol. Rev. 51, 334 (2020).

Oliveira, P. M. A. & Nunes, P. M. S. An endemic lizard of Catimbau National Park, Pernambuco, Brazil, found in the stomach contents of Tropidurus cocorobensis (Squamata: Tropiduridae). Herpetol. Notes 13, 305–307 (2020).

Pagel, G. S., Leite, A. K., Oliveira, L. C. C. & Tinôco, A. S. Tropidurus hispidus (Neotropical Lava Lizard). Diet. Herpetol. Rev. 51(1), 134 (2020).

Pergentino, H. E. S., Nicola, P. A., Pereira, L. C. M., Novelli, I. A. & Ribeiro, L. B. A new case of predation on a lizard by Tropidurus hispidus (Squamata, Tropiduridae), including a list of saurophagy events with lizards from this genus as predators in Brazil. Herpetol. Notes 10, 225–228 (2017).

Sousa, J. D. et al. Novel behavioral observations of the lizard Tropidurus hispidus (Squamata: Tropiduridae) in Northeastern Brazil. Cuadernos de Herpetología 35, 305–317 (2021).

Bruinjé, A. C., Coelho, F. E., Paiva, T. M. & Costa, G. C. Aggression, color signaling, and performance of the male color morphs of a Brazilian lizard (Tropidurus semitaeniatus). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 73, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-019-2673-0 (2019).

Silva, D. N., Cassel, M., Ferreira, A. & Mehanna, M. Courtship, copulation, and territorialistic behaviors of Tropidurus torquatus (Tropiduridae) in a fragment of Cerrado in Central-West Brazil. Rev. Ambient. 14(4), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.48180/ambientale.v14i4.390 (2022).

Maia-Carneiro, T., Motta-Tavares, T. & Rocha, C. F. D. Tropidurus hispidus (Lagartixa; Peters’ Lava Lizard). Cannibalism. Herpetol. Rev. 51(2), 336 (2020).

Mayntz, D. & Toft, S. Nutritional value of cannibalism and the role of starvation and nutrient imbalance for cannibalistic tendencies in a generalist predator. J. Anim. Ecol. 75, 288–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2006.01046.x (2006).

Polis, G. A. & Myers, C. A. A survey of intraspecific predation among reptiles and amphibians. J. Herpetol. 19, 99–107. https://doi.org/10.2307/1564425 (1985).

Tavares, R. V., Sousa, I. T. F., Araújo, A. B. P. & Kokubum, M. N. C. Ameivula ocellifera (Spix’s Whiptail). Saurophagy. Herpetol. Rev. 48(3), 631–632 (2017).

Polis, G. A. The effect of cannibalism on the demography and activity of a natural population of desert scorpions. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 7, 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00302515 (1980).

Rosenheim, J. A. & Schreiber, S. J. Pathways to the density-dependent expression of cannibalism, and consequences for regulated population dynamics. Ecology 103(10), e3785. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3785 (2022).

Villar, M. M., Bechsgaard, J., Bilde, T., Albo, M. J. & Tomasco, I. H. Impact of pre-copulatory sexual cannibalism on genetic diversity and efficacy of selection. Biol. Lett. 20(5), 20230505. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2023.0505 (2024).

Sasal, P. Nest guarding in a damselfish: Evidence of a role for parasites. J. Fish Biol. 68, 1215–1221. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-1112.2006.01010.x (2006).

Stott, M. K. & Pulin, R. Parasites and parental care in male upland bullies (Eleotridae). J. Fish Biol. 48, 283–291. https://doi.org/10.1006/jfbi.1996.0026 (1996).

Moura, M. R. et al. Geographical and socioeconomic determinants of species discovery trends in a biodiversity hotspot. Biodivers. Conserv. 220, 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.01.024 (2018).

Endler, J. A. Interactions between predator and prey. In Behavioural Ecology (eds Krebs, J. R. & Davies, N. B.) 169–196 (Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1991).

Kikuchi, D. W. et al. The evolution and ecology of multiple antipredator defences. J. Evol. Biol. 36(7), 975–991 (2023).

Dinerstein, E. et al. An ecoregion-based approach to protecting half the terrestrial realm. BioScience 67(6), 534–545. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/bix014 (2017).

QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System (Version 3.32). Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project (2024).

Bastian, M., Heymann, S. & Jacomy, M. Gephi: An open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, vol. 3(1), 361–362. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v3i1.13937 (2009).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis 212 (Springer, 2016).

Fox, & Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd edn (Sage, Thousand Oaks, 2019). Available from: http://z.umn.edu/carbook.

Wickham, H. et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 4(43), 1686. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.01686 (2019).

Garnier, S. viridis: Colorblind-Friendly Color Maps for R. R package version 0.6.5. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=viridis (2023)

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020). http://www.Rproject.org/.

Vilela, B. & Villalobos, F. letsR: A new R package for data handling and analysis in macroecology. Methods Ecol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12401 (2015).

Bivand, R., Keitt, T. & Rowlingson, B. rgdal: Bindings for the ‘Geospatial’ Data Abstraction Library. http://rgdal.r-forge.r-project.org, https://proj.org, https://r-forge.r-project.org/projects/rgdal/ (2023).

Pebesma, E. J. & Bivand, R. S. Classes and methods for spatial data in R: The sp package. R News 5(2), 9–13 (2005).

Becker, R. A. & Wilks, A. R. maps: Draw Geographical Maps. R Version by Ray Brownrigg. Enhancements by Thomas P. Minka and Alex Deckmyn. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=maps (2023).

Hijmans, R. J., Bivand, R., Pebesma, E. & Sumner, M. D. terra: Spatial Data Analysis. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=terra (2024).

Hijmans, R. J. raster: Geographic Data Analysis and Modeling. R package version 2.6-7. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=raster (2017).

Hijmans, R. J., Phillips, S., Leathwick, J., Elith, J. & Hijmans, M. R. J. Package ‘dismo’. Circles 9(1), 1–68 (2017).

Bivand, R. & Rundel, C. rgeos: Interface to Geometry Engine—Open Source (GEOS). R Package Version 0.3-20. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rgeos (2016).

Olivoto, T. & Lúcio, A. D. metan: An R package for multi-environment trial analysis. Methods Ecol. Evol. 11(6), 783–789. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13384 (2020).

Kuhn, M. Building predictive models in R using the caret package. J. Stat. Softw. 28(5), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v028.i05 (2008).

Gorelick, N. et al. Google earth engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 202, 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2017.06.031 (2017).

Fan, Y. et al. Applications of structural equation modeling (SEM) in ecological studies: An updated review. Ecol. Process. 5(19), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-016-0063-3 (2016).

Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02 (2012).

Mitchell, A. & Bergmann, P. J. Thermal and moisture habitat preferences do not maximize jumping performance in frogs. Funct. Ecol. 30(5), 733–742. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12535 (2016).

Titon Junior, B. & Gomes, F. R. Relation between water balance and climatic variables associated with the geographical distribution of anurans. PLoS ONE 10(10), e0140761. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140761 (2015).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010933404324 (2001).

Breiman, L., Friedman, J., Stone, C. J. & Olshen, R. A. Classification and Regression Trees 368 (Taylor & Francis, 1984).

Hu, J. & Szymczak, S. A review on longitudinal data analysis with random forest. Brief. Bioinform. 24(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbad002 (2023).

Biau, G. & Scornet, E. A random forest guided tour. Test 25, 197–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11749-016-0481-7 (2016).

Liaw, A. & Wiener, M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R News 2(3), 18–22 (2002).

Olsen, L. H. B., Glad, I. K., Jullum, M. & Aas, K. A comparative study of methods for estimating model-agnostic Shapley value explanations. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 38, 1782–1829. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10618-024-01016-z (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank Vinicius Anelli, Felipe Eduardo Alves Coelho, and Marcelo Gehara for their suggestions. We thank Lucas Rosado for the saurophagy illustration and Wilson Xavier Guillory for reviewing the language of the manuscript. UFS thanks the grant and fellowship provided by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP #2022/10081-7; #2022/11096-8).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H.A.L. conceived the idea and supervised. P.M.A.O., U.F.S., and J.H.A.L wrote, reviewed and edited. P.M.A.O., U.F.S., and J.H.A.L analyzed the data. P.M.A.O., U.F.S., J.D.S., A.V.A.M., N.V.N.S., and J.H.A.L collected the data. All authors contributed critically to drafting and gave final approval to publish.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oliveira, P.M.A., Souza, U.F., de Sousa, J.D. et al. Unraveling patterns and drivers of saurophagy in South American lizards. Sci Rep 15, 6519 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89810-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89810-7