Abstract

Multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) generalised spatial modulation (GSM) systems represent a pivotal advancement in wireless communication technology. These systems have unlocked the potential for enhanced data rates and enhanced error performance (EP). Therefore, this research delves into a strategy aimed at elevating the EP within MIMO-GSM systems. This strategy involves the integration of MIMO-GSM systems with both generalised quadrature spatial modulation (GQSM) and the concept of labelling diversity (LD). Two schemes namely multiple active antenna generalised spatial modulation with labelling diversity (MAA-GSM-LD) and generalised complex quadrature spatial modulation with labelling diversity (GCQSM-LD) are proposed. The first scheme is MAA-GSM-LD, which builds on conventional generalised spatial modulation (C-GSM) by incorporating it with multiple active antennas and optimised labelling maps that have a maximised minimum product distance (M-MPD) between constellations. This M-MPD helps improve detection, thereby improving the EP of MIMO-GSM schemes. Four symbols are sent simultaneously per time slot in MAA-GSM-LD. The second scheme (GCQSM-LD), builds on MAA-GSM-LD by splitting the four symbols created in MAA-GSM-LD into the quadrature and in-phase dimensions, thereby avoiding inter-antenna synchronisation and improving the EP of MIMO-SM systems. In this study, analytical mathematical expressions were developed to determine both the union-bound and upper-bound average bit error rate (ABER) for the MAA-GSM-LD and GCQSM-LD schemes. These evaluations were conducted over independent and identically distributed Rayleigh frequency-flat fading channels. Monte Carlo simulations were utilised to validate the accuracy of these expressions. The findings suggest that as the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) increases, the average bit error probability (ABEP) closely approximates the outcomes of the simulations. Moreover, the simulation results indicate enhancements in the EP of both MAA-GSM-LD and GCQSM-LD schemes compared to various MIMO-SM schemes such as generalised complex quadrature spatial modulation (GCQSM) and generalised SM multiplexing two symbols (MIMO-GSM) while maintaining the same spectral efficiency (SE). For MAA-GSM-LD, an improvement in the EP of 1.0 dB with an SE of 11 bits/s/Hz is seen in \(6\times 4\) MAA-GSM-LD C-16-QAM over \(6\times 4\) GQSM C-16-QAM and 4.3 dB over \(6\times 4\) Golden codeword-GSM-C-64QAM. For GCQSM-LD, an improvement in the EP of 4.7 dB with an SE of 14 bits/s/Hz is seen in \(8\times 4\) GCQSM-LD C-16-QAM over \(4\times 4\) GCQSM-C-64-QAM and 3.7 dB over \(4\times 4\) Generalised quadrature spatial modulation with antenna grouping (GQSM-AG)-C-32QAM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

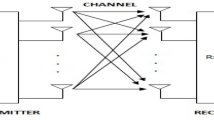

Due to the ever-growing demand for data-intensive applications and seamless connectivity, wireless communication networks have widely embraced multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) systems1,2. These MIMO systems utilise multiple antennas at both the transmitter and receiver ends, taking advantage of spatial diversity to enhance link capacity and reliability1,3. However, the reliability of MIMO systems can be impacted by factors such as channel impairments, inter-symbol interference (ISI), and noise4. This research delves into an investigation of the synergistic incorporation of three innovative techniques: Conventional generalised spatial modulation (C-GSM), conventional generalised quadrature spatial modulation (C-GQSM), and space-time labelling diversity (STLD). This integration aims to enhance the error performance (EP) and/or spectral efficiency (SE) of MIMO systems.

Conventional spatial modulation (C-SM) is a technique designed to enhance SE by jointly mapping information bits onto the spatial constellation (transmit antenna indices) and the signal constellation5,6,7. Previous studies, such as Naidoo et al.7, have compared C-SM with other MIMO transmission schemes, highlighting its advantages in terms of avoiding inter-channel interference (ICI) and achieving inter-antenna synchronization (IAS). However, the SE of C-SM is influenced by the practical number of transmit antennas, which led to the development of C-GSM to address this limitation8,9.

C-GSM addresses the limitation posed by C-SM, which mandates that the number of transmit antennas must be a power of two. Instead, C-GSM allows a block of information bits to be associated with both a constellation symbol and a transmit antenna index. Unlike C-SM, where only one transmit antenna is active at a time, C-GSM improves the SE by a factor equivalent to the base-two logarithm of the number of antenna combinations. This decrease in the required number of transmit antennas achieves the same SE8,10.

Furthermore, a spatial modulation scheme involving multiple active transmit antennas (MIMO-GSM), as proposed in Wang et al.11, leverages C-GSM to enhance the SE of MIMO systems. It allows the simultaneous transmission of multiple symbols using multiple transmitters, thereby improving both SE and EP by increasing spatial diversity.

To enhance the EP of SM systems, Mesleh et al.,12, introduced a scheme known as conventional quadrature spatial modulation (C-QSM). C-QSM expands the spatial constellation into two dimensions, specifically the in-phase (I) and quadrature (Q) dimensions. It effectively eliminates inter-channel interference (ICI) by modulating the I and Q components using cosine and sine carriers, respectively12,13,14. In a study by Kim et al.,15, C-QSM was employed in antenna selection schemes to improve EP while simultaneously reducing detection complexity. However, it is important to note that C-QSM has a drawback. It necessitates a higher number of transmit antennas when compared to conventional spatial multiplexing (C-SMux). This limitation can restrict the potential for EP improvement in SM systems13.

Additionally, in the quest to enhance the EP of SM systems while minimising the required number of transmit antennas, Mohaisen et al.16, introduced a generalised complex quadrature spatial modulation (GCQSM) scheme. GCQSM builds upon the foundation of C-QSM by fusing elements from C-GSM with those of C-QSM. This integration results in improved EP by simultaneously transmitting two amplitude/phase modulated symbols sourced from two distinct constellations during each channel utilisation. Their study demonstrates that this amalgamation of C-GSM and C-QSM enhances robustness against IAS, consequently elevating the reliability and SE of wireless communication links. Despite the heightened complexity encountered at both the transmitter and receiver ends, the equilibrium between performance gains and added complexity renders GCQSM a practical choice for implementation.

Furthermore, Castillo et al.13, introduced a technique called generalised quadrature spatial modulation with antenna grouping (GQSM-AG) to also enhance the EP of SM systems. GQSM-AG similarly leverages attributes from both C-GSM and C-QSM. Their study illustrates that this combination results in an improved EP compared to C-QSM, C-GSM, and various other MIMO-SM techniques.

Another important technique for improving reliability in wireless communication systems, especially in MIMO systems, is space-time labelling diversity (STLD). As an extension of space-time block coding (STBC) and spatial modulation (SM), STLD uses both spatial and temporal diversity to mitigate fading and improve overall system performance17,18. Recently, STLD was proposed as a novel diversity technique that achieves higher diversity gain without requiring additional transmit or receive antennas19. By using optimised labelling maps, STLD can maximise the minimum product distance (MPD) of space-time block codes (STBCs), and empirical evidence has shown its superiority over STBCs in terms of the EP under identical channel conditions20. This is seen in20, where optimised labelling maps maximise the MPD of Alamouti STBC codewords, eliminating the need for encoding or bit interleaving, reducing computational complexity (CC), and ensuring efficient bandwidth utilisation. Also, evidence of improving the EP of MIMO-SM systems is seen in21, where optimised labelling maps were used in a scheme called labelling diversity (LD) for media-based space-time block coded spatial modulation21. The design of optimised labelling maps has been greatly discussed in Xu et al.19 and in Krasicki,18. Optimised labelling maps used in this paper were adapted from19 and are given in Appendix A.1.

Motivation

Motivated to improve the EP, this paper proposes fusing GSM systems and GQSM systems with optimised labelling maps as they were found to maximise the MPD of STBCs in20,22 and in turn, this led to an improved EP in STBCs19,20,21. In23 a scheme that focuses on enhancing QSM through techniques such as precoding, antenna selection, or hybrid modulation strategies was proposed. While these methods can improve performance, they do not address the specific optimisation of the labelling process19,20,21. Thus, fusing GSM and GQSM systems with optimised labelling maps is distinct in that it specifically targets the bit-to-symbol mapping process by introducing multiple labelling strategies, thereby achieving performance gains through labelling diversity19,20,21. This strategy is complementary to, but distinct from, the enhancements proposed in23. Hence, two techniques called multiple active antenna generalised spatial modulation with LD (MAA-GSM-LD) and generalised complex quadrature spatial modulation with LD (GCQSM-LD) are proposed. Similarly to24, MAA-GSM-LD builds on C-GSM and optimised labelling maps, by fusing the attributes of C-GSM and those of LD in optimised maps19.

In Wang et al.11, a MIMO-GSM scheme was proposed and it exhibited improved EP as compared to C-GSM and C-SM systems. Thus, in11, it was shown that multiple active transmit antennas increase spatial diversity thereby improving robustness against fading. Hence, to improve the EP of GSM systems, this paper, entails the proposal of a scheme that extends MIMO-GSM into transmitting four symbols simultaneously, two from Gray-coded quadrature amplitude modulated (QAM) constellations and two from optimised labelling QAM maps. This MAA-GSM-LD proposed scheme fuses MIMO-GSM with optimised labelling maps because it was shown in20 and21, that optimised labelling maps increase the robustness of GSM systems against fading, hence improving the EP of GSM systems.

Also, to improve on the EP of MIMO-GQSM schemes like in25, this paper, also entails the proposal of extending the MAA-GSM-LD scheme with C-QSM attributes of expanding the spatial domain into the I-phase and Q phase dimensions. This proposed scheme is herein named generalised complex quadrature spatial modulation with labelling diversity (GCQSM-LD). This proposed scheme also builds on complex generalised spatial modulation by Mohaisen16. Instead of sending two symbols from C-QAM constellations, it draws four symbols, (two from conventional Gray-coded QAM constellations and two from optimised labelling QAM maps). The four symbols are then split into imaginary and real parts of the signal, which are then sent by the I-phase and Q-phase dimensions, respectively12,14. This further improves the robustness of the proposed schemes as the I and Q spatial domains are designed to reduce IAS, thereby improving robustness against channel fading.

Thus, the core contributions of this paper are:

-

1.

Proposal of a new GSM scheme called MAA-GSM-LD which incorporates MIMO-GSM and optimised LD maps that maximise the MPD of STBCs, which in turn improves the EP of the STBCs.

-

2.

Derivation of a union-bound average bit error rate (ABER) expression for the MAA-GSM-LD scheme over independent and identically distributed (i.i.d) Rayleigh frequency-flat fading (RF-FD) channels.

-

3.

Validation of the derived analytical bound for the MAA-GSM-LD scheme using Monte Carlo simulation results.

-

4.

Proposal of a scheme called GCQSM-LD that extends the MAA-GSM-LD scheme into the C-QSM domain by using optimised LD maps with GCQSM.

-

5.

Derivation of an upper bound ABER expression for the GCQSM-LD scheme in i.i.d RF-FD channels.

-

6.

Validation of the derived analytical bound for the GCQSM-LD scheme using Monte Carlo simulation results.

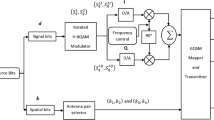

Finally, the structure of the paper is as follows. The introduction of the proposed MAA-GSM-LD scheme is elaborated in Section “Proposed MAA-GSM-LD system model”. It is depicted as a MIMO \(N_T \times N_R\) M-QAM system shown in Figs. 1 and 2. Section “Proposed GCQSM-LD system model” introduces the second proposed scheme called GCQSM-LD, followed by Section “MLD CCA of the proposed MAA-GSM-LD and GCQSM-LD schemes”, which provides the maximum likelihood detection (MLD) computational complexity analysis (CCA) based on real-valued multiplications and additions of the proposed schemes. Then, in Section “EP analysis of MAA-GSM-LD and GCQSM-LD”, the EP analysis of the proposed MAA-GSM-LD and GCQSM-LD schemes is presented. Section “Simulation and numerical results analysis” discusses the results of this paper, and finally, the paper concludes in Section “Conclusion”.

Notation

In this paper, using mathematical notation, the symbol \((\cdot )^*\) corresponds to the complex conjugate, while \(|\ \cdot \ |\) signifies the Euclidean norm operator. Column vectors are indicated using bold lowercase letters, whereas matrices are represented by uppercase letters. Scalar quantities are denoted by regular letters. A set of complex matrices with dimensions \(S\times L\) is described by \(\mathbb {C}^{S\times L}\). When dealing with complex arguments, \(\Re (\cdot )\) and \(j(\cdot )\) stand for the real and imaginary components, respectively. The function \(Q(\cdot )\) is employed to express the Gaussian Q-function, \(E\{\cdot \}\) is used to denote the expectation operator, \(\underset{w}{\operatorname {argmin}}\{{\cdot }\}\) and \(\underset{w}{\operatorname {argmax}}\{{\cdot }\}\) represent finding the argument’s minimum or maximum value concerning the variable w, respectively. The operators \([\cdot ]^T\) and \((\cdot )^H\) refer to the transpose and Hermitian operators, respectively. The Frobenius norm operator is denoted as \(\left\Vert \cdot \right\Vert _F\). The notation \(\lfloor \cdot \rfloor _{2^p}\) signifies the largest integer that is less than or equal to the argument and is a positive integer that is a power of 2 raised to the p. Finally, \(\left( {\begin{array}{c}\cdot \\ \cdot \end{array}}\right)\) is used to denote the binomial coefficient of the argument.

Proposed MAA-GSM-LD system model

The proposed MAA-GSM-LD scheme depicted in Figs. 1 and 2, is designed as an \(N_R \times N_T\) system. It takes an input data stream, which is categorised into two distinct types: spatial input bits (representing antenna pair indices) and four M-QAM symbol bits. In the first category, spatial information, a set of spatial input bits (\(\mathfrak {D}=\log _{2}N_c\)) is allocated to a specific generalised \(K^{th}\) transmit antenna pair, denoted as (\(k_l\) for \(1\le l\le 4\)). These antenna pairs are responsible for transmitting four M-QAM symbols. For example, if we consider a scenario with \(N_T\) transmit antennas, there are \(n=\left( {\begin{array}{c}N_T\\ N_A\end{array}}\right)\) possible transmit antenna pairs. However, only \(N_c=\lfloor \log _{2}\left( {\begin{array}{c}N_T\\ N_A\end{array}}\right) \rfloor _{2^p}\) of these pairs are allowed for transmission, where \(N_c\) is selected from the range \(N_c\le n\). It is worth noting that the choice of \(N_A\) has been addressed in previous work, such as8, and for the proposed MAA-GSM-LD scheme, the customary value is set to 4 as discussed in16.

Table 1 provides an illustrative mapping that outlines the associations between antenna pairs, their corresponding bit indices, and the rotation angles denoted as \(\theta _k\). The purpose of these rotation angles is to minimise the potential interference caused by the overlapping of antenna pairs, as described in16,26. For further details regarding the selection of antenna pairs and the optimal values for \(\theta _k\), the discussion can be found in16,26.

The second category of the input data stream is the message/or symbols bit stream \(\varvec{b}\). The message bit stream is partitioned into two bit streams \(\varvec{b}_t=\begin{bmatrix} b_{t,1} b_{t,2}\ldots b_{t,r}\end{bmatrix}\), with \(t\in [1:2]\) and \(r=\)log\(_2\) M. Bit stream \(\varvec{b}_1\) is fed into a mapper (\(\mathfrak {G_1}\)) and bit stream \(\varvec{b}_2\) is fed into an optimised labelling mapper (\(\mathfrak {G_2}\)). Mapper (\(\mathfrak {G_1}\)) follows the conventional Gray-coded approach, and input bit streams \(\varvec{b}_t\), are mapped onto M-QAM signal constellation sets to yield two symbols \(S _{q}^{1}=\mathfrak {G}^M_1(\varvec{b}_1)\) and \(S _{q}^{2}=\mathfrak {G}^M_1(\varvec{b}_2)\) where \(q\in [1:M]\).

In mapper \(\mathfrak {G_2}\), the same bit streams (\(\varvec{b}_t\)), are mapped onto M-QAM signal constellation sets in the Argand plane, yielding symbols \(\tilde{ S }_{q}^{1}=\mathfrak {G}^M_2(\varvec{b}_1)\) and \(\tilde{ S }_{q}^{2}=\mathfrak {G}^M_2(\varvec{b}_2)\). It is assumed that the set of all order symbol pairs is contained in set \(V_{LD}\), \(E\{| S _{q}^{i}|^2\}=1\) and \(E\{|\tilde{ S }_{q}^{i}|^2\}=1\), with \(i\in [1:2]\). However, the design of mapper \(\mathfrak {G_2}\) is different from that of mapper \(\mathfrak {G_1}\). The design of mapper \(\mathfrak {G_2}\), is the one that ensures LD17,18,19, and its design follows that detailed in18,19. For this paper, the used 16-QAM Gray-coded labelling map (\(\mathfrak {G}^{16}_1\)) and the optimised labelling map (\(\mathfrak {G}^{16}_2\)) were adopted from19, whereas the 64-QAM Gray-coded labelling map (\(\mathfrak {G}^{64}_1\)) and the optimised labelling map (\(\mathfrak {G}^{64}_2\)) were adopted from20. An example of the labelling maps used in this paper is found in Appendix A.1.

The modulated symbols \(S _{q}^{1}\), \(S _{q}^{2}\), \(\tilde{ S }_{q}^{1}\), and \(\tilde{ S }_{q}^{2}\), originating from the two mappers, are simultaneously transmitted by four transmit antennas (\(k_l\), where (\(1\le l\le 4\)) within each time slot. These symbols collectively form an \(N_T\times 1\) transmit vector denoted as \(\textbf{x}\), as depicted in Fig. 3. Consequently, vector \(\textbf{x}\) contains four non-zero elements, and the positions of these four non-zero elements correspond to the indices of the four chosen active transmit antennas. The SE of the proposed MAA-GSM-LD scheme can be calculated using (1).

At the receiver, the signal is given by \(\textbf{y}\in \mathbb {C}^{N_R\times 1}\) (2), as

where the fading channel matrix is represented as \(\textbf{H}\in \mathbb {C}^{N_R\times N_T}\), and the vector \(\textbf{n}\in \mathbb {C}^{N_R\times 1}\) denotes the additive white Gaussian noise AWGN. Each \(\textbf{h}_{k_l}\) (where \(1\le l\le N_T\)) refers to the lth column vector within the channel gain matrix \(\textbf{H}\), which is defined as \(\textbf{H}=\begin{bmatrix}\textbf{h}_{k_1}&\textbf{h}_{k_2}&\textbf{h}_{k_3}&...&\textbf{h}_{k{N_T}}\end{bmatrix}\), and each \(\textbf{h}_{k_l}\) itself can be expressed as \(\textbf{h}_{k_l}=\begin{bmatrix}{h}_{1k_l}&{h}_{2k_l}&{h}_{3k_l}&...&{h}_{N_Rk_l}\end{bmatrix}^T\). It is important to highlight that both the elements of the vector \(\textbf{n}\) and the matrix \(\textbf{H}\) are assumed to be i.i.d Gaussian random variables (GRVs) with a distribution of \(CN (0,1)\), respectively. Lastly, \(\rho\) symbolises the average signal-to-noise ratio (SNR).

The optimal maximum likelihood detection (MLD) procedure for the proposed scheme can be expressed as shown in (3). This process involves jointly estimating the indices of the transmission antenna pairs (\(\hat{K}\)) and the transmitted symbols (\(S _{q}^{1}\), \(S _{q}^{2}\), \(\tilde{ S }_{q}^{1}\), and \(\tilde{ S }_{q}^{2}\))13,16,27,28. The procedure can be described as follows,

where \(\hat{\textbf{x}}\) is the estimated received vector shown in Fig. 4.

Proposed GCQSM-LD system model

Consider a proposed scheme with dimensions \(N_R \times N_T\) similar to the one described in Section “Proposed GCQSM-LD system model”. This proposed GCQSM-LD scheme utilises the same input data stream as the scheme in Section “Proposed GCQSM-LD system model”, which is partitioned into two categories: spatial input bits (representing antenna pair indices) and four M-QAM symbol bits.

For this proposed system, there are \(n=\left( {\begin{array}{c}N_T\\ N_A\end{array}}\right)\) possible transmit antenna pairs, of which only \(N_c=\Big \lfloor \log _{2}\left( {\begin{array}{c}N_T\\ N_A\end{array}}\right) \Big \rfloor _{2^p}\) pairs are deemed suitable for transmission, with \(N_c\) being less than or equal to n. It is worth noting that the choice of \(N_A\) has been addressed in8, with the commonly adopted value for the proposed GCQSM-LD scheme being 416. In the first category, spatial information is represented, where spatial input bits (\(\mathfrak {D}=\log _{2}N_c\)) are allocated to a distinct generalised \(K^{th}\) antenna pair of transmit antennas (\(k_l\), where \(1\le l\le 4\)), corresponding to the I dimension of the system. The same set of \(\mathfrak {D}\) bits is assigned to a separate generalised \(K^{th}\) antenna pair of transmit antennas (\(k_l\), where \(5\le l\le 8\)), designated for the Q dimension of the system.

Detailed mapping tables of the grouped bits, covering I dimension transmit antenna pairs and Q dimension transmit antenna pair combinations, are provided in Tables 5 and 6 in Appendix A.1. Notably, the antenna mappings for the I and Q dimensions are distinct. This differentiation is essential to prevent ICI or the concurrent transmission of a mixed signal comprising real and imaginary components from the same antenna pair. Such differentiation contributes to enhancing the EP of the proposed system12,16. The application of rotation angles (\(\theta _k\)) to various transmit antenna pairs, as discussed in Section “Proposed GCQSM-LD system model”, further aids in minimising ICI resulting from overlapping antenna pairs26. Comprehensive discussions concerning the selection of antenna pairs and the determination of optimal \(\theta _k\) are found in Section “Proposed GCQSM-LD system model”10,16,26.

The second category within the input data stream encompasses a message or symbol bit sequence, represented as \(\varvec{b}\). The processing of this bit stream \(\varvec{b}\) follows the same procedures as detailed in Section “2”, leading to the generation of four modulated M-QAM symbols (\(S _{q}^{1}\), \(S _{q}^{2}\), \(\tilde{ S }_{q}^{1}\), and \(\tilde{ S }_{q}^{2}\)). These modulated symbols are further disassembled into their individual real and imaginary components, denoted as (\(S _{q}^{1I}+j S _{q}^{1Q}\), \(S _{q}^{2I}+j S _{q}^{2Q}\), \(\tilde{ S }_{q}^{1I}+j\tilde{ S }_{q}^{1Q}\), and \(\tilde{ S }_{q}^{2I}+j\tilde{ S }_{q}^{2Q}\)). Subsequently, the real components of these symbols are transmitted through the I dimension using the in-phase transmit antenna pairs (\(k_l\), where \(1\le l\le 4\)). On the other hand, the imaginary parts of these symbols are transmitted through the Q dimension using the quadrature antenna pairs (\(k_l\), where \(5\le l\le 8\)).

As a result, these disassembled symbols are concurrently transmitted using eight transmit antennas within a single time slot. They are encapsulated in the form of an \(N_T\times 1\) transmit vector \(\textbf{x}\), as depicted in Fig. 5. Notably, this vector \(\textbf{x}\) comprises eight non-zero elements, corresponding to the four real parts and the four imaginary parts of the modulated symbols originating from Section “Proposed GCQSM-LD system model”. The positions of these eight non-zero elements align with the indices of the eight selected active transmit antennas. The SE of the proposed GCQSM-LD scheme is computed in a manner identical to that given by (1).

At the receiver, the signal is given by \(\textbf{y}\in \mathbb {C}^{N_R\times 1}\) (4), as

where \(\textbf{U} = \bigg (\textbf{h}_{k_1} S _{q}^{1I} + \textbf{h}_{k_2} S _{q}^{2I} + \textbf{h}_{k_3}\tilde{ S }_{q}^{1I} + \textbf{h}_{k_4}\tilde{ S }_{q}^{2I}\bigg )e^{j\theta _k}\), \(\textbf{W}=\bigg (\textbf{h}_{k_5} S _{q}^{1Q} + \textbf{h}_{k_6} S _{q}^{2Q} + \textbf{h}_{k_7}\tilde{ S }_{q}^{1Q} + \textbf{h}_{k_8}\tilde{ S }_{q}^{2Q}\bigg )e^{j\theta _k}\), \(\textbf{H}\in \mathbb {C}^{N_R\times N_T}\) and \(\textbf{n}\in \mathbb {C}^{N_R\times 1}\) are similar to those discussed in MAA-GSM-LD Section “Proposed GCQSM-LD system model”.

The MLD procedure for the proposed scheme is articulated within (5). This method encompasses the concurrent estimation of both the indices of the transmission antenna pairs (\(\hat{K}\)) and the transmitted symbols (\(S {q}^{1}\), \(S {q}^{2}\), \(\tilde{ S }{q}^{1}\), and \(\tilde{ S }{q}^{2}\)). This approach has been elaborated on in previous studies, such as13,16,27,28.

where \(\hat{\textbf{x}}\) is the estimated received vector shown in Fig. 6.

MLD CCA of the proposed MAA-GSM-LD and GCQSM-LD schemes

The CCA for the MAA-GSM-LD scheme shares similarities with the approach described in previous work11,29,30, specifically11 and30. As for the GCQSM-LD scheme, its CCA is akin to the method outlined in the work by Holoubi et al.30. The complexity analysis for the two proposed systems involves assessing the number of arithmetic operations (e.g., additions, multiplications) required to execute key processes, such as symbol mapping, demodulation, and detection. This includes evaluating the complexity of the Gray-coded and optimized labelling maps used for QAM, as well as the detection complexity at the receiver.

The CCA of MAA-GSM-LD is similar to that given as \(N_RM^{N_A}(N_A+2)N_c\) in11 and that of GCQSM-LD is similar to that given in30, as \((20N_R-1)2^{\mathfrak {m}}\). As seen in Table 2, the MAA-GSM-LD scheme has the highest CC as compared to the GCQSM-LD scheme. Both the proposed schemes have a high CC as compared to that of C-QSM as discussed in Sibanda et al.,25. In25, C-QSM was one of the schemes that had a very high CC, hence this means that the two proposed schemes have the disadvantage of a high complexity ratio. Also, as seen from Fig. 7, the CC of the proposed MAA-GSM-LD and GCQSM-LD schemes increases with the number of receive antennas. Likewise, Fig. 8 illustrates an increasing CC as the order of quadrature modulation increases for both the proposed schemes (MAA-GSM-LD and GCQSM-LD). It should be noted that the proposed schemes are limited in terms of QAM modulation order (16-QAM and 64-QAM). Thus, Fig. 8 has other orders of QAM modulation used for clearly illustrating how the CC increases as M increases. The outcome of the CCA discussed in this section, shows that the proposed schemes are ideal for low orders of QAM modulations and a few receive antennas. Given the notable high CC exhibited by the proposed scheme, the authors plan to address this limitation in their future work by developing simplified detection algorithms such as adaptive modulation techniques, power allocation schemes or low complexity detection methods, which could further enhance the system performance, as a solution. Also, to curb high complexity detection on the receiver side, the authors will look at methods like machine learning-based detection algorithms or hybrid receivers that combine ML with other detection strategies to enhance performance, particularly in scenarios with imperfect channel knowledge or high mobility.

EP analysis of MAA-GSM-LD and GCQSM-LD

In this section, the union bound and upper bound are used to derive the theoretical ABEP for the MAA-GSM-LD and GCQSM-LD schemes, respectively, following the approach outlined in10,16,27,28.

EP analysis of MAA-GSM-LD

The detection process detailed in Section “Proposed MAA-GSM-LD System model” employs a collaborative detection approach. It adopts a methodology akin to prior studies such as7,10,11, where separate processes for QAM symbols and transmit antenna pair indices are assumed. The detection process outlined in Section “Proposed MAA-GSM-LD System model” encompasses two categories of errors. The first category concerns estimating the average bit error probability (ABEP) of the transmit antenna pair indices (\(P_a\)), assuming perfect detection of the message symbols, while the second category pertains to errors in estimating the message symbols (\(P_d\)), given perfect detection of the transmit antenna pair index. Consequently, following the methodology outlined in11, the overall ABEP can be bounded by a union of these errors, as illustrated in (6).

It should be emphasised that assuming independent estimation procedures might not accurately reflect reality, as the optimal ML detector simultaneously detects both the message symbols and the transmit antenna pair index. The notion of independent estimation processes depicts an idealised situation7. Consequently, the subsequent Sections “Analytical ABEP of M-QAM symbols estimation” and “Analytical ABEP of transmit antenna pair index estimation” involve deriving the ABEP for each estimation process independently.

Analytical ABEP of M-QAM symbols estimation

This sub-subsection, entails the derivation of the probability of detection (\(P_d\)), for estimating the ABEP of M-QAM symbols. This estimation assumes perfect detection of transmit antenna pair indices and is based on the system model given in Eq. (2). The formulation presented follows the methodology introduced by Pillay et al.10, along with insights from Naidoo et al.7. Consequently, by adopting the approach of Pillay et al.10, and considering the presence of four active transmitters, the expression for \(P_d\) is found as

where \(P=\bigg (\frac{4}{\beta \rho +4}\bigg )^{N_R}\), \(R=\bigg (\frac{2}{\beta \rho +2}\bigg )^{N_R}\), \(Z=\bigg (\frac{4\sin ^2{\Theta _\omega }}{\beta \rho +4\sin ^2{\Theta _{\omega }}}\bigg )\), \(\alpha =\bigg (1-\frac{1}{\sqrt{M}}\bigg )\), \(\beta =\frac{3}{M-1}\) and \(\Theta =\frac{i\pi }{4n}\). The constant \(n\ge 10\) is necessary to ensure convergence between the Gaussian Q-function and its trapezoidal approximation.

Analytical ABEP of transmit antenna pair index estimation

The formulation of the ABEP related to the identification of transmit antenna pair indices, denoted as \(P_a\), aligns with the methodology presented in10 and7. It is worth noting that, in contrast to the C-SM and C-GSM schemes, the MAA-GSM-LD system incorporates four active transmit antennas during each transmission interval. Consequently, by following the approach established by Naidoo et al.7, and Pillay et al.10, the expression for \(P_a\) can be derived as

where \(N(k,\hat{k})\) is the number of bits in error between the transmit antenna pair index K and the estimated transmit antenna pair index \(\hat{K}\). \(\mu _\alpha =\frac{1}{2}\left( 1-\sqrt{\frac{\sigma _{\alpha ^2}}{1+\sigma _{\alpha ^2}}}\right)\) and \(\sigma _{\alpha ^2}=\frac{\rho }{8}| S _{q}^{1}|^2\) as described in 10 and 7.

EP analysis of GCQSM-LD

From13,16,25,27,28,30, the ABEP of GCQSM-LD can be derived following the well-known bounding techniques. Thus, following the same approach as16,27,28, the ABEP of GCQSM-LD is defined as

where \(N_{\left( q,\hat{q}\right) }\), represents the count of erroneous bits linked to the pairwise error probability (PEP) event denoted as \(P(\textbf{x}\rightarrow \hat{\textbf{x}}|\textbf{H})\). This PEP event pertains to the comparison between the transmitted vector \(\textbf{x}\) and the received vector \(\hat{\textbf{x}}\). The formulation for the conditional PEP is expressed as follows:

where \(\mu _v=2\sin ^2\left( \frac{v\pi }{2n}\right)\), \(n\ge 6\) is the number of summations for convergence, \(d_i=\bigg [\left( S _q^{iI}- S _{\hat{q}}^{iI}\right) e^{j\theta _k}\bigg ]\), \(d_{i+2}=\bigg [ \left( \tilde{ S }_{q}^{iI} -\tilde{ S }_{\hat{q}}^{iI} \right) e^{j\theta _k} \bigg ]\), \(d_{(i+4)}=\bigg [\left( S _q^{iQ}- S _{\hat{q}}^{iQ}\right) e^{j\theta _k}\bigg ]\), \(d_{i+6}=\bigg [ \left( \tilde{ S }_{q}^{iQ}- \tilde{ S }_{\hat{q}}^{iQ} \right) e^{j\theta _k} \bigg ]\) and \(i\in [1:2]\). \(D_l=|d_l|\) and \(l\in [1:8]\). The derivation of the conditional PEP is found in Appendix A.2.

Diversity analysis of the GCQSM-LD scheme

It follows on the simplification of (10) that,

where \(D_u=\sum _{l=1}^8(D_l)^2\). At high SNRs, \(\left( \frac{\rho D_u}{32}>>1\right)\) and \(\left( \frac{\rho D_u}{16\mu _v}>>1\right)\). Hence, \(P(\textbf{x}\rightarrow \hat{\textbf{x}})\) can be approximated at high SNRs as

Further simplification leads (12) into (13),

The overall diversity gain (\(G_c\)) attained by a MIMO-SM scheme has been defined in31, as

where \(P_b\) denotes the overall probability of error as a function of SNR. Hence given \(P_b(SNR)=P(\textbf{x}\rightarrow \hat{\textbf{x}})\) as given in (13), then (14) becomes

Hence substituting (13) into (15), leads to (16).

where \(\beta =\left( \frac{1}{2n}\right) \left[ \left( \frac{1}{2}\right) + \sum _{v=1}^{n-1}\left( \frac{2}{\mu _v}\right) ^{-N_R}\right] \left( \frac{ D_u}{32}\right) ^{-N_R}\).

Since \(\lim _{\rho \rightarrow \infty } \bigg (\frac{\log (\beta )}{\log (\rho )}\bigg )=0\), therefore \(G_c=N_R\). Hence the diversity gain of the proposed system is \(N_R\).

Simulation and numerical results analysis

This section presents simulation results for the proposed MAA-GSM-LD and GCQSM-LD systems with varying numbers of transmit antennas. This section also entails the comparison of these schemes with a selection of the best-performing schemes from24 and25. The schemes chosen for comparison include GCQSM, MIMO-GSM, Golden codeword-based GSM (GCW-GSM), and GQSM-AG.

To evaluate the ABEP for the GCW-GSM scheme in the comparisons, equation (4) from24 was used. For MIMO-GSM, equation (16) from Wang et al.11 was used, and for GQSM-AG, equation (9) from13 was utilised.

The goal of this section is to validate the theoretical performance bounds that were derived in Sections “EP analysis of MAA-GSM-LD” and “EP analysis of GCQSM-LD”. The BER of the proposed schemes was assessed using Monte Carlo simulations conducted over i.i.d RF-FF channels with AWGN. Specifically, the BER performance of MAA-GSM-LD was evaluated at different SEs (\(\mathfrak {m}=11\) bits/s/Hz and \(\mathfrak {m}=15\) bits/s/Hz), and the BER performance of GCQSM-LD was evaluated at \(\mathfrak {m}=14\) bits/s/Hz and \(\mathfrak {m}=18\) bits/s/Hz as functions of the average SNR. The results for these four SEs are depicted in Figs. 9, 10, 11 and 12. All comparisons were made under consistent conditions, including \(N_R=4\) antennas in all scenarios, the same SE, optimal MLD method, and at a BER of \(1\times 10^{-5}\) for reference.

To begin, Figs. 9 and 11 illustrates the BER performance of the MAA-GSM-LD and GCQSM-LD schemes, respectively, with varying numbers of transmit antennas, specifically \(N_T=6\) and \(N_T=8\). In these Figs. 9 and 11, the analytical results for both MAA-GSM-LD and GCQSM-LD are validated through simulations, and it is evident that the agreement between the simulations and the analytical derivations tightens as the SNR values increase. This tight correspondence at high SNR levels can be attributed to the predominant influence of the probability of detection (\(P_d\)) in MAA-GSM-LD and the upper-bound ABER performance in the GCQSM-LD scheme.

Moving on, Fig. 10 and Table 3 provide insight into the EP gains of the proposed \(6\times 4\) MAA-GSM-LD scheme when compared to other \(6\times 4\) schemes with the same SE of \(\mathfrak {m}=11\) bits/s/Hz. As indicated in Fig. 10 and Table 3, the proposed MAA-GSM-LD scheme demonstrates a performance gain of 1.0 dB over the \(6\times 4\) GCQSM-C-16-QAM scheme, 4.3 dB over the \(6\times 4\) GCW-GSM-C-64-QAM scheme, and 1.2 dB over the \(6\times 4\) MIMO-GSM-C-16-QAM scheme. Wang et al.11, discussed MIMO-GSM, highlighting its superior performance over C-SM and C-GSM schemes with similar SEs. Additionally, in25, it was observed that GCQSM schemes outperformed MIMO-GSM schemes. Consequently, the proposed MAA-GSM-LD scheme exhibits performance gains over all the schemes in this study, surpassing GCQSM and the best-performing schemes from25 and the existing literature11,26. This improvement can likely be attributed to the use of optimised labelling maps with multiple active antennas, which enhances spatial diversity and, consequently, the EP.

Figure 12 and Table 4 provide a performance comparison for the proposed GCQSM-LD scheme at an SE of \(\mathfrak {m}=14\) bits/s/Hz, with \(N_R=4\) antennas and varying numbers of transmit antennas. In Fig. 12, the \(8\times 4\) GCQSM-LD-C-16-QAM scheme is compared with two of the best \(4\times 4\) schemes from24 and25, all operating at an SE of \(\mathfrak {m}=14\) bits/s/Hz. As depicted in Fig. 12 and Table 4, the proposed \(8\times 6\) GCQSM-LD-C-16-QAM scheme outperforms the \(4\times 4\) GQSM-AG-C-32-QAM scheme by 3.6 dB and the \(4\times 4\) GCQSM-C-64-QAM scheme by 4.7 dB. This demonstrates that the proposed GCQSM-LD scheme surpasses all the schemes from24 and25, outperforming GQSM-AG, which was one of the best schemes discussed in the literature11,13,25,26. This performance can likely be attributed to the use of optimised labelling maps, multiple active antennas, and QSM attributes, all of which enhance spatial diversity and, in turn, improve the EP of the proposed GCQSM-LD scheme.

Finally, it should be noted that the proposed schemes are limited in terms of the order of modulation (M) (LD with 16-QAM and 64-QAM only), which determines the SE (\(\mathfrak {m}\)) and the number of receive antennas as discussed in the CCA of Section “MLD CCA of the proposed MAA-GSM-LD and GCQSM-LDschemes”. MAA-GSM-LD is limited to 11 and 15 bits/s/Hz, whereas, GCQSM-LD is limited to 14 and 18 bits/s/Hz. Anything above the speculated number of SEs results in a much worse MLD complexity that inhibits the systems. Hence it should be noted that due to the aforementioned limitations, the proposed schemes could not be compared against each other and other various schemes of different SE (\(\mathfrak {m}\)) as they would be incompatible.

Conclusion

This study, introduced the proposed MAA-GSM-LD and GCQSM-LD schemes as enhancements to improve the EP of existing GSM and GQSM schemes. These schemes represent an evolution of GSM and GQSM by integrating optimised labelling maps and multiple active antennas into the GSM and GQSM systems. Additionally, this research derived analytical formulas for union and upper-bound EP for the proposed schemes, focusing on i.i.d RF-FF channels. The derived analytical bounds were validated through the use of Monte Carlo simulations, demonstrating their increasingly accurate alignment with observed results as SNR values rose. The outcomes of the investigation revealed that the proposed MAA-GSM-LD and GCQSM-LD schemes outperformed the most prominent schemes in the literature, including GCQSM, GQSM-AG, and MIMO-GSM. Consequently, it can be concluded that MAA-GSM-LD and GCQSM-LD offer viable solutions for enhancing the EP of MIMO-SM schemes. The proposed technique is well-suited for next-generation wireless communication systems, including 5G, Internet of Things networks, massive MIMO systems and satellite and deep space communication networks, where the aforementioned communication network systems demand high spectral efficiency, robustness to interference, and low error rates, all of which are addressed by the optimized labelling maps and the enhanced error performance provided by our GQSM framework. However, it is essential to acknowledge that the proposed schemes have a high complexity MLD process. As part of future research, the authors aim to explore and develop low-complexity detection methods for these proposed schemes. Furthermore, the authors intend to extend the work by exploring the incorporation of Golden codewords to the MAA-GSM-LD and GCQSM-LD schemes, to further enhance the SE of MIMO-SM systems.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Agubor, C. K., Opara, F. K. & Eze, G. N. A review of diversity techniques for wireless communications. Acad. Res. Int. (ARInt.) 4(2), 157–167 (2013).

Liu, M., Helard, M., Helard, J. F. & Crussiere, M. A fast decodable full-rate STBC with high coding gain for 4\(\times\) 2 MIMO systems. In IEEE 24th Annual International Symposium on Personal, Indoor, and Mobile Radio Communications (PIMRC). IEEE 2013, 677–681 (2013).

Love, D. J. & Heath, R. W. Equal gain transmission in multiple-input multiple-output wireless systems. IEEE Trans. Commun. 51(7), 1102–1110 (2003).

Simon, M. K. & Alouini, M. S. Digital communication over generalized fading channels: A unified approach to performance analysis (Wiley-Interscience Publication, 2002).

Mesleh, R. Y., Haas, H., Sinanovic, S., Ahn, C. W. & Yun, S. Spatial modulation. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 57(4), 2228–2241 (2008).

Jeganathan, J., Ghrayeb, A. & Szczecinski, L. Spatial modulation: Optimal detection and performance analysis. IEEE Commun. Lett. 12(8), 545–547 (2008).

Naidoo, N. R., Xu, H. & Quazi, T. A. Spatial modulation: Optimal detector asymptotic performance and multiple-stage detection. IET Commun. 5(10), 1368–1376 (2011).

Younis, A., Serafimovski, N., Mesleh, R. & Haas, H. Generalised spatial modulation. In 2010 Conference Record of the Forty Fourth Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems and Computers. IEEE, pp. 1498–1502 (2010)

Afridi, S. & Hassan, S. A. Spectrally efficient adaptive generalized spatial modulation MIMO systems. In 14th IEEE Annual Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC). IEEE, 2017, 260–263 (2017).

Pillay, R., Pillay, N. & Xu, H. Improved error performance for generalised spatial modulation with enhanced spectral efficiency. Int. J. Commun Syst 33(2), e4176 (2020).

Wang, J., Jia, S. & Song, J. Generalised spatial modulation system with multiple active transmit antennas and low complexity detection scheme. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 11(4), 1605–1615 (2012).

Mesleh, R. Y., Ikki, S. S. & Aggoune, H. M. Quadrature spatial modulation. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 64(6), 2738–2742 (2014).

Castillo-Soria, F., Cortez-González, J., Ramirez-Gutierrez, R., Fermín, M.M.-B. & Soriano-Equigua, L. Generalized quadrature spatial modulation scheme using antenna grouping. ETRI J. 39(5), 707–717 (2017).

Oladoyinbo, S., Pillay, N. & Xu, H. Adaptive quadrature spatial modulation. IETE Tech. Rev. 37(6), 579–590 (2020).

Kim, S. Antenna selection schemes in quadrature spatial modulation systems. ETRI J. 38(4), 606–611 (2016).

Mohaisen, M. Generalised complex quadrature spatial modulation. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2019(1), 3137927 (2019).

Krasicki, M. Improved labelling diversity for iteratively-decoded multi-antenna systems. In 7th International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing Conference. IEEE,2011, 359–364 (2011).

Krasicki, M. Essence of 16-qam labelling diversity. Electron. Lett. 49(8), 567–569 (2013).

Xu, H., Govindasamy, K. & Pillay, N. Uncoded space-time labeling diversity. IEEE Commun. Lett. 20(8), 1511–1514 (2016).

Govindasamy, K., Xu, H. & Pillay, N. Space-time block coded spatial modulation with labelling diversity. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 31(1), e3395 (2018).

Adejumobi, B. S. & Shongwe, T. Labeling diversity for media-based space-time block coded spatial modulation. IEEE Access 8(1), 99870–99879 (2020).

Krouk, S. E. Modulation and coding techniques in wireless communications (Wiley, 2011).

Gudla, V. V., Gamini, S., Kumaravelu, V. B. & Soria, F. R. C. Performance evaluation of fully quadrature spatial modulation under various channel fading scenarios. In 2022 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Signal Processing (AISP). IEEE, pp. 1–5 (2022)

Sibanda, N., Xu, H. & Pillay, N. Golden codeword-based generalized spatial modulation. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 39(10), e5144 (2022).

Sibanda, N., Xu, H. & Pillay, N. Error performance analysis of generalized quadrature spatial modulation using h-8qam. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 1–13 (2022).

Naidoo, N. R. Enhanced performance and efficiency schemes for generalised spatial modulation. Ph.D. dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal (2017)

Xiao, L. et al. Compressed-sensing assisted spatial multiplexing aided spatial modulation. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 17(2), 794–807 (2018).

Xiao, L. et al. Compressive sensing assisted generalized quadrature spatial modulation for massive mimo systems. IEEE Trans. Commun. 67(7), 4795–4810 (2019).

Xiao, L. et al. A unified bit-to-symbol mapping for generalized constellation modulation. China Commun. 20(6), 229–239 (2023).

Holoubi, T., Murtala, S., Muchena, N. & Mohaisen, M. On the performance of improved quadrature spatial modulation. ETRI J. 42(4), 562–574 (2020).

Zheng, L. & Tse, D. Diversity and multiplexing: A fundamental tradeoff in multiple-antenna channels. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 49(5), 1073–1096 (2003).

Cogen, F. & Aydin, E. Hexagonal quadrature amplitude modulation aided spatial modulation. In 2019 11th International Conference on Electrical and Electronics Engineering (ELECO). IEEE, pp. 730–733 (2017)

Cogen, F. & Aydin, E. Performance analysis of hexagonal qam constellations on quadrature spatial modulation with perfect and imperfect channel estimation. Phys. Commun. 47(1), 101379 (2021).

Koc, A., Altunbas, I. & Basar, E. Full-duplex spatial modulation systems under imperfect channel state information. In 2017 24th International Conference on Telecommunications (ICT). IEEE, pp. 1–5 (2017)

Xu, H. Symbol error probability for generalised selection combining reception of M-QAM. SAIEE Afr. Res. J. 100(3), 68–71 (2009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A Appendices

A Appendices

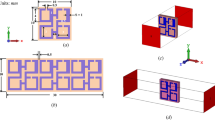

Gray-coded maps and optimised labelling maps

See Figs. 13, 14, 15 and 16; Tables 5, 6 and 7

16-QAM Gray-coded labelling map \(\mathfrak {G}^{16}_1\)19.

Optimised 16-QAM labelling map \(\mathfrak {G}^{16}_2\)19.

64-QAM Gray-coded labelling map \(\mathfrak {G}^{64}_1\)20.

Optimised 64-QAM labelling map \(\mathfrak {G}^{64}_2\)20.

Derivation of the PEP

Based on the equivalent system model in (4), the conditional PEP, \(P(\textbf{x}\rightarrow \hat{\textbf{x}})\) can be formulated as

Substituting (4) into (17) leads to

where \(A=\left\Vert \textbf{n}\right\Vert _F^2\), \(B=\frac{\rho }{8}\left\Vert \sum _{l=1}^8\textbf{h}_{k_l}d_l + \textbf{n}\right\Vert _F^2\), \(d_i=\bigg [\left( S _q^{iI}- S _{\hat{q}}^{iI}\right) e^{j\theta _k}\bigg ]\), \(d_{i+2}=\bigg [ \left( \tilde{ S }_{q}^{iI} -\tilde{ S }_{\hat{q}}^{iI} \right) e^{j\theta _k} \bigg ]\), \(d_{(i+4)}=\bigg [\left( S _q^{iQ}- S _{\hat{q}}^{iQ}\right) e^{j\theta _k}\bigg ]\), \(d_{i+6}=\bigg [ \left( \tilde{ S }_{q}^{iQ}- \tilde{ S }_{\hat{q}}^{iQ} \right) e^{j\theta _k} \bigg ]\) and \(i\in [1:2]\).

Equation (18) can also be rewritten as;

where \(C =\frac{\rho }{8}\left\Vert \sum _{l=1}^8\textbf{h}_{k_l}d_l \right\Vert _F^2\) and \(D=2\Re \big \{\sqrt{\frac{\rho }{8}}\textbf{n}^H\left( \sum _{l=1}^8\textbf{h}_{k_l}d_l \right) \big \}\).

Simplifying Eq. (19) leads to (20).

As \(\textbf{n}^H\) is an element of \(\mathbb {C}^{1\times N_R}\), with each entry defined as \(\textbf{n}^H=\begin{bmatrix} n_1^*&n_2^*&n_3^*&\ldots&n_{N_R}^*\end{bmatrix}\), and since these entries are Gaussian distributed, it follows that each entry of \(\Re \bigg \{\sqrt{\frac{\rho }{8}}\textbf{n}^H\textbf{h}_{k_z}d_z\bigg \}\), for \(z\in [1:8]\), is also a GRV. These entries have a distribution of \(N\left( 0,\frac{\rho }{8}\left| d_z\right| ^2\sum _{l=1}^{N_R}\left| h_{k_z}^l\right| ^2\right)\). Consequently, it implies that our decision variable is likewise Gaussian distributed, and can be represented as \(\Re \bigg \{\sqrt{\frac{\rho }{8}}\textbf{n}^H\bigg (\sum _{l=1}^8\textbf{h}_{k_l}d_l\bigg )\bigg \}\sim N\left( 0,\frac{\rho }{16}\left\Vert \sum _{l=1}^8\textbf{h}_{k_l}d_l\right\Vert _F^2\right)\), leading to

where \(\omega _g=\frac{\rho }{16}\left\Vert \left( \sum _{l=1}^8\textbf{h}_{k_l}d_l\right) \right\Vert _F^2=\frac{\rho }{16}\left\Vert \textbf{H}_k\textbf{G}_k\right\Vert _F^2= \frac{\rho }{16}\left\Vert \textbf{H}_k\right\Vert _F^2\left\Vert \textbf{G}_k\right\Vert _F^2\), with \(\textbf{H}_{k}=\begin{bmatrix} \textbf{h}_{k_1}&\textbf{h}_{k_2}&\cdot \cdot \cdot&\textbf{h}_{k_l}\end{bmatrix}\), \(\textbf{G}_k=\begin{bmatrix}d_1&d_2&\cdot \cdot \cdot&d_l\end{bmatrix}^T\), \(\{l\}\in [1:8]\). Similarly, based on (11) in Koc et al.34, \(\omega _g\) are chi-squared RVs with \(2N_R\) degrees of freedom defined as \(\omega _g=\sum _{t=1}^{2N_R} \alpha _{\omega _{g,t}}^2\) with \(\alpha _{\omega _{g,t}}^2\sim N(0,\sigma _{\omega _g}^2)\) and \(\sigma _{\omega _g}^2=\frac{\rho }{16}\big (\sum _{l=1}^8(D_l)^2\big )\). \(D_l=|d_l|\) and \(l\in [1:8]\).

The conditional PEP in (21) can then be expressed as

where the probability density function of \(\omega _g\) is given in4 as

The trapezoidal transformation of the Q-function in35, is given as

where \(n\ge 6\) is the number of summations for convergence and \(S_v=\exp (-\frac{z^2}{2\sin ^2\left( \frac{v\pi }{2n}\right) })\).

Using the trapezoidal transformation (24) on (21) and then substituting into (22) yields

where \(\mu _v=2\sin ^2\left( \frac{v\pi }{2n}\right)\).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sibanda, N., Xu, H. & Pillay, N. Error performance analysis of generalized quadrature spatial modulation with labelling diversity. Sci Rep 15, 6155 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89872-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89872-7