Abstract

Foodborne illnesses are often caused by microbial contamination during preparation or storage. In this work, stable nanoemulsions of clindamycin were prepared using Mentha piperita essential oil (MEO) as a nanocarrier delivery system. Response Surface Methodology was used to optimize the key variables for clindamycin nanoemulsion formulation, including 4.83, 2.83, and 0.14%w/w surfactant, essential oil, and clindamycin, respectively. The stability of MEO/clindamycin nanoemulsion (MEO/C NE) with a mean droplet size of 75.46 ± 3.2 nm was monitored over 3 months. The antibacterial activity of MEO/C NE and bulk compounds against E. coli bacterium was compared using a conventional method and a microfluidic chip. A significant difference in the antibacterial activity was observed by employing a microfluidic chip as compared to the conventional technique, probably due to a high contact surface area between the nanodroplets and bacterial membrane. In the microfluidic chip, the E. coli was completely inhibited in 30 min, whereas 3 h was needed for complete inhibition using the conventional method. The results of this study highlight the significance of nanoemulsion delivery systems to improve the antimicrobial activity of clindamycin and also microfluidic technology as a fast and reliable technique for examining antibiotics and nano delivery systems against microorganisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biological contaminants that can result in foodborne illnesses are known as foodborne pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, and parasites. The emergence of two or more cases of a similar illness brought on by the consumption of a food is known as a foodborne disease outbreak. Escherichia coli (E. coli) is among the more frequently reported food pathogens that is found normally in warm-blooded creatures’ lower intestines. While most strains of E. coli are not harmful, some can result in severe food poisoning1. The bacteria known as Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) is capable of causing serious foodborne illnesses. E. coli may evolve in vegetables and other foods and live in the environment for long period of time2. Since E. coli is the most prevalent Gram-negative infection in humans, antibiotic resistance in this pathogen is especially concerning3. Consequently, it is crucial to use natural compounds to combat antibiotic resistance since they present an acceptable replacement for conventional antibiotics, which are losing their efficacy as a result of the emergence of resistant bacteria. It has been demonstrated that natural compounds possessing antibacterial qualities can offer a viable path forward for the development of novel therapies4. The antibacterial effects of natural compounds EOs and the synergistic effect of two or more EO components5,6 have been distinguished by several researchers. The antibacterial properties of EOs result from components that act synergistically or additively, acting at multiple sites of action at the cellular level rather than through a single mechanism7. Recently, much consideration has been given to the isolation and utilization of new bioactive compounds with antioxidant and or antimicrobial activity from botanical sources8. For example, Nostro and Papalia examined and confirmed the antibacterial activity of carvacrol against a variety of food-borne pathogens and microorganisms9. As an advanced strategy in this area, our team has already published information on the EOs’ enhanced antibacterial activity through the use of nanoemulsification techniques10,11,12,13,14. Nanoemulsions are defined as fine colloidal dispersions of water-in-oil or oil-in-water droplets within the size range of 10–600 nm, used in pharmaceuticals and biomedical industries15. Nanoemulsions are showing promising horizons for the development of novel cosmetics, diagnostics, and pharmaceuticals as well as biotechnology products. The terms submicron emulsion (SME), small emulsion, and ultrafine emulsion are also used synonymously. Nanoemulsions usually consist of heterogeneous mixtures of lipid and aqueous phases wherein stability is achieved through the use of suitable materials known as emulsifiers16,17. The use of nanoemulsions as delivery systems has been shown to extend the residence time of drugs in the body. Previous studies have shown the use of nanoemulsion technology to improve the bioavailability of lipophilic drugs and antibiotics18.

Simultaneous administration of existing antibiotics and essential oils (EOs) has been experimentally investigated as an alternative strategy for treating infections caused by drug-resistant bacteria19. Some studies have confirmed the synergistic and/or additive effects of EOs and some antibiotics against bacteria20. Indeed, nanoemulsification provides a large contact surface area. This is more intensified when a highly efficient microfluidic chip is employed to attain a high contact area between bioactive compounds and cell membranes. When it comes to detecting antimicrobial activity, microfluidic devices have several advantages over traditional techniques including fast antibacterial compound testing in less than an hour, small quantities of the required reagents and medium and versatile microfluidic designs for special purposes. Furthermore, microfluidic devices can support modular detection techniques and comprehensive cultivation regimens, enabling more accurate and effective investigation of the bacterial cell membrane interaction with antibacterial agents. This is in contrast to the conventional techniques, which frequently need more intricate handling and longer incubation times. Moreover, visual investigation of the bacterial status upon treatment is possible using microfluidic technology.

Incorporating appropriate natural compounds along with an antibiotic such as clindamycin in nanoemulsions can be considered a practical solution to increase the contact surfaces and hence the antibacterial activity of antibiotics.

This study aims to investigate the possibility of formulating a stable Mentha piperita essential oil/clindamycin nanoemulsion (MEO/C NE) for antibacterial activity experiments. At first, the effect of important formulation variables, including surfactant, EO, and clindamycin concentrations on the nanoemulsion properties like mean particle size and stability was studied using the Response Surface Methodology (RSM) technique. Then, the application of a microfluidic chip for evaluating the antibacterial activities of nanoemulsions against E. coli bacterium was considered and compared to the conventional method. The amounts of potassium, nucleic acid, and protein release were scrutinized to assess the extent of bacterial cell destruction. The microscopic structural changes elucidated the morphology of nanoemulsion and bacteria strains after the microfluidic treatment and conventional morphology technique.

Experimental method

Material and method

The study used E. coli ATCC 25,922 in 2X Nutrient Broth containing 15% v/v Glycerol supplied as a cryoprotectant, the organisms were kept as freezer stock at – 20 °C. Before starting any experiment, a fresh culture was created on a Nutrient agar plate (which CONDA Pronadisa sold). Imports from Merck, Millipore (Darmstadt, 93 Germany) were phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), neutral red, and non-ionic surfactants Span 80 and Tween 80. Clindamycin base (Caspian Tamin CO., Iran) and Mentha piperita EO (Tabibdaru CO., Kashan, Iran) were purchased. A high-speed homogenizer (SilentCrusher M, Heidolph) from Germany, a Light Microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany) were used to detect the bacteria. Scanning Electron Microscope (Hitachi S-4700, Tokyo, Japan), Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) device (Nanophox Sympatec GmbH, Claushtal, Germany), and UV–visible spectrophotometer (Bio-photometer, Eppendorf AG, Hamburg) from Germany were utilized for further experiments.

Design of experiment

The implementation of design of experiments (DOE) including orthogonal array design, Box-Behnken design (BBD), and central composite design (CCD) to optimize technical processes and formulations is expanding in research laboratories. Based on some initial testing, the appropriate ranges including surfactant 3.0, 4.0, 5.0 w/w%, essential oil 2.0, 3.0, 4.0 w/w%, and clindamycin 0.01, 0.055, 0.10 w/w% were chosen. 17 experiments were selected based on BBD, including 5 central point replications (Table S1) to estimate reasonably the experimental error. It should be noted that each characterization test of formulations was repeated three times and the average values were reported. The quadratic regression model was executed to predict the relationship between the nanoemulsion droplet size and variables as demonstrated in Eq. (1):

where Y denotes the droplet size (nm); β0 is the intercept coefficient, β1, β2 and β3 stands with the main effect coefficients, β11, β22, and β33 are the squared coefficients, and β12, β13, and β23 show the interaction coefficients. Design-Expert Software (State-Ease Inc., version 7.0.0) was used to analyze the experimental data and evaluate the predicted responses.

Nanoemulsion preparation

Clindamycin-loaded nanoemulsions were prepared by dissolving clindamycin in the EO and Span and then mixing in deionized water containing a non-ionic surfactant. A solution of Tween80 in deionized water (the aqueous phase) was added to the mixture of clindamycin, EO, and Span80 (the oil phase). A high-speed homogenizer was used to prepare the nanoemulsion samples21. The whole mixture was homogenized under the stirring rate of 19,000 rpm for 20 min. The mean particle diameter of the nanoemulsions stored at – 4 °C was scanned over 3 months to determine the stability of the nanoemulsion samples.

Microfluidic system

The techniques of microchip design and fabrication were the subject of an extensive report in our previous work10. The microchannel made of PDMS (Dow Corning Crop, USA) was created using the microlithography method. SU-8 photoresist film was used in photolithography to create the master molds. The PDMS liquid (Sylgard 184) and PDMS curing agent were then carefully blended well in a 10:1 ratio and poured onto the SU-8 molds. PDMS began to separate from the molds as it was curing at 90 °C for 30 min. In the end, the oxygen plasma procedure was used to bind the two PDMS layers for 1 min at 8 mbar and 40 W. The inlets and outlets of the microchannels were created using a biopsy punch with a 1.25 mm width.

E. Coli bacterium cultivation and preparation

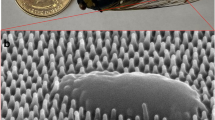

The preparation of the E. coli bacterium depicted in Fig. 1 was described in detail in a previous study11. Briefly, a colony was removed and added to sterilize (MHB) broth medium and incubated under aerobic conditions at 37 °C and 200 rpm, followed by centrifugation for 10 min at 4000 rpm at 4 °C. 1 mL of neutral red solution (0.04 mg in 100 mL) was added to the obtained extract followed by incubation in the shaker for 10 min at 37 °C. After centrifuging the resultant solution for ten minutes at 4000 rpm at 4 °C, 10 mL of PBS buffer was slowly added.

The obtained solution has been injected into a microfluidic chip. In the quantitative tests, the bacterial suspension was injected directly into the device. It should be noted that the design and manufacture of the chip are described in detail in a previous study10.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC)

To determine the MIC, a continuous two-fold dilution of samples at concentrations of 10 to 0.005 mg/mL was prepared in sterile 96-well plates as described by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). The MIC value was the concentration that completely inhibited the growth of bacteria (the first clear well). Using the microtiter broth dilution technique, the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) was recorded as the minimum sample concentration of 99.9% bacterial death after culturing at 37 °C for 24 h22. Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Cell membrane integrity

The integrity of bacterial cell membranes was assessed as described in detail in a previous study11. Briefly, the integrity of the cell membrane was evaluated by monitoring the discharge of intracellular materials including nucleotides and proteins at 260 and 280 nm, respectively.

Time kill assay

A time-kill assay was performed to confirm the antibacterial effects of clindamycin, MEO, and MEO/C NE bacterial growth inhibitory. The samples were collected at four intervals (1, 2, 3, and 4 h) during the time-kill assay. The original bacterium solution was further diluted with a sodium chloride solution (0.085%W/V) to facilitate the counting of colony units. Subsequently, 100µL specimens were extracted from the dilutions. To facilitate the counting of colony units, a predefined amount of outflow was sampled in the microfluidic chip at the predetermined residence time. The colony counting unit underwent the same procedure. Following a 24-hour incubation period at 37 °C, the initial bacterial solution was serially diluted using a sodium chloride solution (0.085%W/V) before the plate colony count was carried out22. Lastly, the bacterial cell viability and growth inhibition were calculated based on the following definitions:

Result and discussion

Optimization of nanoemulsion formulation

A subclass of RSM, Box Behnken Design (BBD), was used to determine the most appropriate nanoemulsion droplet size targeting the highest stability and biological response. The droplet size of the nanoemulsion was calculated using the DLS procedure for the combination of the independent parameters, which includes the percentages of surfactant (A), EO (B), and (C) clindamycin given in Table S1. The mean droplet size was calculated as the average of three measurements. The BBD comprises a total of 17 proposed experimental runs, including five repeatable center points (Table S1). The suggested correlations are shown in Eqs. 3 and 4 as functions of the independent variables for the droplet size, both in real and coded values.

Table 1 displays the ANOVA statistical analysis for the regression model. From Table 1, the low p-value (p < 0.0002) and /or high F-value (F = 24.24) p-confirm the statistical significance of the predicted model. Also, the Lack of Fit index is not significant (0.1309) relative to the pure error indicating the model fits well and the independent variable has considerable effects on the response. The other statistics of the model like the coefficient of determination (\(\:{R}^{2}\)) was 0.9689, Adjusted R2 = 0.9289, adequate precision = 17.766, and predicted R2 = 0.6274, standard deviation = 4.68, coefficient of variation (C.V%) = 4.79, suggesting a strong connection between experimental and projected values. As a result, the resulting model is sufficient to draw a response surface curve and predict stability conditions for maximizing the stability values.

By extension, Fig. S1a. displays a plot of the actual outcomes versus what was anticipated. It helps identify a value or set of data that the regression model is unable to correctly forecast. These graphs demonstrate how well the expected values match the experimental data. The residual plots versus the fitted responses, or a curve of the residuals against the expected response values, are also displayed in Fig. S1b. Plotting should continue with random scatter, that is, a fixed range of residuals throughout the graph. The findings collected validate the proposed model’s correctness. The discrepancy between the actual information and the expected response is shown in terms of the ordinary probability plot of residuals in Fig. S1c. This indicates whether the data points must follow a straight line for the residuals to mimic a normal distribution (Fig. S1c). The points follow a straight line that is surrounded by a normal distribution, as seen in Fig. S1c.

Interactive effect of droplet size of NE formulation factors

The ultimate droplet size is significantly influenced by the concentration of the constituents that make up the nanoemulsion. High surfactant concentrations have been suggested to raise the risk of toxicity in food23,24. Herein, the EO, clindamycin, and surfactant percentages were altered to scrutinize the suitable NEs-based clindamycin droplet size. The quadratic polynomial models’ 3D response surface contour plots, which depict the relationships between interacting independent and dependent variables, are displayed in Fig. 2. Figure 2a illustrates the mutual effect of surfactant and essential oil percentages on the droplet size of the MEO/C NE. In Fig. 2a, a significant interaction between the surfactant and essential oil variables is considered. At the lower constant value of surfactant (3 to 4 w/w%) increasing the essential oil leads to a significant increase in the droplet size, while when surfactant is fixed at a higher value (4.5 to 5 w/w%) there is no remarkable change in mean droplet size. In addition to reducing the droplet size, increasing the essential oil concentration is the main goal of this study. Concentrations can be moderated to see the noticeable effects of essential oils. In this case, the droplet size will also be moderate. The ideal situation occurs when the essential oil and surfactant amounts are in the middle of the curve because a lower surfactant proportion is advantageous. These findings corroborate those of25 who proposed that an increase in surfactant % causes a decrease in the droplet size of cinnamon oil nanoemulsion. Figure 2b shows the impact of clindamycin concentration and surfactant on the MEO/C NE droplet size. As observed, with the simultaneous increase in clindamycin concentration at constant surfactant concentration, the droplet size increased significantly, which could refer to the clindamycin droplet size. Also, increasing the surfactant concentration to a specific amount leads to a larger droplet size until a peak is reached, then with more increasing concentration the droplet size can be reduced. Surfactants typically lower the free energy required for the generation of nanoemulsions. By lowering the surface tension at the water-oil interface, surfactants which are made up of both hydrophilic and hydrophobic components interlink the space between the aqueous and oil phases26,27. This implies that a decrease in the nanoemulsion droplet size could result from raising the Tween 80 content. Figure 2c shows the interaction of essential oil and clindamycin on the mean droplet size of MEO/C NE. From Fig. 2c the saddle-type curve implies that an increase in both clindamycin and essential oil concentrations leads to larger droplet size. The computed p-values in Table 1 confirm that the influence of the independent variable is statistically significant.

Optimization of the droplet size of nanoformulation

The regression model was employed to attain the optimal values for the selected factors. Three various proposed cases by DOE software are re-performed to verify the accuracy of the fitted correlation (Table 2). It was shown that both experimental and predicted values are in close agreement, approving that the fitted model is reliable. The DLS plots associated with the mean particle diameter of the nanoemulsions are 75.46 ± 3.2 nm, 73.62 ± 4.4 nm, and 99.35 ± 2.6 nm illustrated in Fig. S2a, b, and c. To assess the encapsulation efficacy percentage (EE%) of clindamycin in nanoparticles, a colorimetric method using ferric acid ion as a colorimetric agent has been utilized28. Briefly, stock solutions of clindamycin and ferric ion were prepared, as described in supporting information. Then, to plot a calibration curve, clindamycin-ferric ion standards ranging from 10 to 250 µg/mL were prepared, and the UV absorption in 590 was evaluated (Fig. S4). The prepared nanoemulsion was separated into two distinct phases (organic and aqueous) by adding KCl (Fig. S5) as described by Klaus et al.29. By adding the ferric chloride solution to the organic phase and upon color change, the absorption was evaluated at 590 nm and the concentration was calculated. The encapsulation EE% was calculated resulting in 59.63% W/W.

After three months of storage at 4 °C, it was demonstrated that the mean particle diameter had not significantly changed, indicating the long-term storage stability (Fig. 3). Following three months of storage, the produced nanoemulsions’ polydispersity index (PDI) was determined to be 0.185, 0.183, and 0.210. The morphology of the prepared nanoemulsion at optimum condition No. 1 is shown in Fig. 4a, which was obtained using the Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Philips-CM30) instrument. The samples’ droplet sizes were spherical and consistent. In addition to Fig. 4b, number frequency histograms display the nanoemulsion’s particle size distribution for optimal condition No. 1 with a droplet size of 64.7 nm on a linear scale. The zeta potential of the prepared nanoemulsions (No 1, 2, and 3) was calculated − 16, − 15.4, and − 15.3 mV respectively (Fig. S3).

Effect of different formulated samples on bacterial inhibition

The MIC and MBC tests for antibacterial activities of prepared samples (Table 3) were evaluated against the E. coli bacterium. The MIC values for (MEO/C NE1), (MEO/C NE2), (MEO/C NE3) exhibited that the optimized formulations are in the same order of magnitude, 0.0195, 0.0390 and 0.0195 mg/mL Comparing MEO NE indicates the effect of nanoemulsification to improve antibacterial activity. However, as can be observed, these values are considerably lower compared to the pure MEO and clindamycin, indicating an enhanced inhibitory effect, which can be ascribed to the impact of the nanoemulsion system as well as active compounds. Other biological studies were conducted after the compound (MEO/C NE1) was determined to be the best experimental formulation based on the obtained data, which showed no discernible variation in the MIC of the optimal points. Other reports, confirm that the antibacterial activity is related to the impact of physicochemical characteristics of essential oil NEs and particle size30,31. It has also been reported that as the droplet size decreases, the electrostatic interaction with the bacterial membrane increases, thereby producing stronger antibacterial potency32. From Table 3, similar trends were observed for MBC values using different test samples. Similar results were reported for ginger oil emulsions33 and, lemongrass oil emulsions34. By binding to the lipid and protein components of the bacterial membrane, nanoemulsions penetrate cell walls and cytoplasmic membranes, resulting in cytolytic and intracellular toxic effects. In other words, the possible mechanism underlying with antibacterial compounds of EO is that they react with the phospholipid components of the cell wall converting them into other compounds such as glycerol and phosphoric acid. Due to this conversion, phospholipid layer can no longer maintain the shape of the cell membrane, consequently, leakage occurs in the cell membrane of the bacteria. It can be seen morphologically in the ghost cell shape of E. coli bacteria as a consequence of this reaction which gives rise to shrinking in the cell membrane and causes the cell to lysis. This process somewhere is also called spheroplast. In visual inspection, it should be noted that some of the lysed cells are partially visible whereas the others are visible in full35.

Figure 5 also presents the variations in concentration of E. coli bacterium (OD600) for different sample formulations at different residences times 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 min in the microfluidic chip, From Fig. 5, the (MEO/C NE) have a high potential to inhibit the growth of bacterial cells compared to clindamycin and MEO alone, and after 30 min of incubation within the microfluidic chip at a concentration of 62.0 µg/mL, nearly all bacteria were suppressed. On the other hand, comparing Fig, 5; Table 3 it is worth noting that the bacteria were killed in 24 h in the conventional method (Table 3), however, based on the results obtained from Fig. 5 it is obvious that after 30 min of incubation, the bacteria are killed demonstrating a more effective way for bactericidal effect.

Further insight into the bactericidal properties of emulsions was gained by intracellular component release assays. Since disruption of cell membrane integrity is always associated with the leakage of intracellular substances, the amount of intracellular leakage into the medium has been monitored36,37. By measuring the release of proteins and nucleic acids after a 30-minute residence period in the microfluidic chip and using the standard approach (MIC concentration), the antibacterial activity of samples (Table S2) against the E. coli strain was evaluated (Fig S6). It is evident from the results in Table S2, that the (MEO/C NE) has higher absorption values as compared to the MEO and clindamycin alone. Fig. S6 presents the release of protein and nucleic acid for samples case study after 6 h by the conventional method at MIC concentration. According to Fig. S6, the highest leakage in terms of OD260 nm and OD280 nm for E. coli were recorded as 0.815 and 0.866. The obtained results show that when comparing the microfluidic chip to traditional approaches, there are noticeable differences, possibly due to the high surface area to volume ratio effect, which leads to the generation of surface forces such as surface tension (a dominant force in the microfluidic chip).

Time kill studies

Dynamic time-kill measurements were conducted to evaluate the bactericidal properties of active compounds (MEO and clindamycin) and nanoemulsion (MEO/C NE) toward the growth of E. coli in the conventional method and microfluidic chip, depicted in Fig. 6a, b, respectively. As can be seen from Fig. 6a the pure active compounds have decreasing trends towards bacterial inhibition, although they show less inhibitory effects than the (MEO/C NE)). It must be noted that the different physicochemical properties associated with MEO and clindamycin result in different action. According to Fig. 6b similar trends in CFU reduction were observed by employing a microfluidic chip. However, there was a considerable difference between residence time in which 30 min is needed using a microchip rather than the conventional method (3 h) for complete bacterial death. Other researchers also suggested that decreasing the particle size leads to an improvement in the antibacterial activity of nano-sized compounds, penetrating the microbial cell wall38,39,40. The authors suggested that the smaller droplet diameters of the nanoemulsions, led to an increase in the bacterial cell surface collision, thus enhancing the antibacterial effect. It has been also showed that the droplet size had a correlation to the antimicrobial efficacy of nanoemulsions.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Utilizing an SEM test, the morphological alterations in E. coli bacteria cells treated with MEO, clindamycin, and MEO/C NE at a concentration of 62.0 µg/mL after 20 min were examined. The shape of an E. coli cell, as seen in Fig. 7a, demonstrated that untreated bacteria have a mostly intact cytoarchitecture, which includes a smooth cell wall or plasma membrane envelope. As can be recognized from Fig. 7b–d the structural changes and damages to the E. coli wall happen when treated with MEO, clindamycin, and MEO/C NE at 20 min. The above compound’s antibacterial activity was thought to be caused by an interaction with phospholipids components of the cell membrane, leading to more penetration of antibiotics and also converting the phospholipids to other compounds including phosphoric acid and glycerol. This conversion causes the bacterial cell membrane to disrupt and leak the constituents because the phospholipid layer cannot maintain the shape of the cell membrane anymore and bacterial lysis or cytolysis occurs41,42. Other proposed mechanisms of antimicrobial action include inhibition of the efflux pumps known to cause antibiotic resistance, disruption of ATP imbalances that alter cellular activity through energy intermediates, protein synthesis, and quorum detection43.

Conclusion

Natural compounds in conjunction with novel approaches like nanotechnology and microfluidic devices can provide new approaches to combat bacterial resistance. The increase in contact surface by nanoemulsion and microfluidic chips as well as the use of active compounds are critical parameters for inhibiting bacterial activity. Using conventional and highly efficient microfluidic techniques, the interaction of optimized MEO/C NE formulations with E. coli bacteria was studied. Natural active compounds interact with bacterial phospholipid bilayer membranes, resulting in cell lysis. MEO/C NE and natural bioactive compound demonstrated highly improved performance for bacterial cell destruction and active penetration than MEO and clindamycin alone. Remarkably, a significantly greater amount (P < 0.05) of internal substances was released from bacterial cell membranes upon nanoemulsion treatment compared to the pure active compounds. Employing microfluidic chips showed superior efficiency in terms of low amount of sample, shorter residence time, and higher release of cytoplasmic materials compared to the conventional method. It was found that providing more efficient contact between the two phases will result in more destruction of the bacterial cell membrane. The current study highlights the potential to enhance the natural compounds containing nanoemulsions antibacterial activity by integrating microfluidic chips as an optimistic, ingenious and economical technology.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Yang, S. C., Lin, C. H., Aljuffali, I. A. & Fang, J. Y. Current pathogenic Escherichia coli foodborne outbreak cases and therapy development. Arch. Microbiol. 199, 811–825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-017-1393-y (2017).

Terajima, J., Izumiya, H., Hara-Kudo, Y. & Ohnishi, M. Shiga toxin (Verotoxin)-producing Escherichia coli and foodborne disease: a review. Food Saf. 5 (2), 35–53. https://doi.org/10.14252/foodsafetyfscj.2016029 (2017).

Thasneem, F. K., Ephrem, A. & Shabaraya, A. R. Fosfomycin: an assessment of its potential for use in the treatment of mdr-Escherichia coli in urinary tract infections. World J. Pharm. Res. 11, 690–703. https://doi.org/10.20959/wjpr202217-26583( (2022).

Álvarez-Martínez, F. J., Barrajón-Catalán, E. & Micol, V. Tackling antibiotic resistance with compounds of natural origin: a comprehensive review. Biomedicines 8 (10), 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines8100405 (2020).

Xiang, F., Zhao, Q., Zhao, K., Pei, H. & Tao, F. The efficacy of composite essential oils against aflatoxigenic fungus aspergillus flavus in maize. Toxins (Basel) 12, 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins12090562 (2020).

Zahi, M. R., El Hattab, M., Liang, H. & Yuan, Q. Enhancing the antimicrobial activity of d-limonene nanoemulsion with the inclusion of ε-polylysine. Food Chem. 221, 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.10.037 (2017).

Sonawane, S. J. et al. Transforming linoleic acid into a nanoemulsion for enhanced activity against methicillin susceptible and resistant Staphylococcus aureus. RSC Adv. 5, 90482–90492. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5RA16248C (2015).

Julianti, E., Rajah, K. K. & Fidrianny, I. Antibacterial activity of ethanolic extract of cinnamon bark, honey, and their combination effects against acne-causing bacteria. Sci. Pharm. 85, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm85020019 (2017).

Nostro, A. & Papalia, T. Antimicrobial activity of carvacrol: current progress and future prospectives. Recent. Pat. Antiinfect. Drug Discov. 7, 28–35. https://doi.org/10.2174/157489112799829684 (2012).

Alvand, Z. M., Rahimi, M. & Rafati, H. A microfluidic chip for visual investigation of the interaction of nanoemulsion of Satureja Khuzistanica essential oil and a model gram-negative bacteria. Int. J. Pharm. 607, 121032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.121032 (2021).

Alvand, Z. M., Rahimi, M. & Rafati, H. Interaction of a natural compound nanoemulsion with Gram negative and Gram positive bacterial membrane; a mechanism based study using a microfluidic chip and DESI technique. Int. J. Pharm. 626, 122181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2022.122181 (2022).

Moghimi, R., Ghaderi, L., Rafati, H., Aliahmadi, A. & McClements, D. J. Superior antibacterial activity of nanoemulsion of Thymus daenensis essential oil against E. coli. Food Chem. 194, 410–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.07.139 (2016).

Mazarei, Z. & Rafati, H. Nanoemulsification of Satureja Khuzestanica essential oil and pure carvacrol; comparison of physicochemical properties and antimicrobial activity against food pathogens. LWT 100, 328–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2018.10.094 (2019).

Darabad, A. H., Rahimi, M. & Rafati, H. Continuous hydrodistillation-ultrasonication flow batch-mode operation system to enhance essential oil extraction from Satureja Khuzistanica and evaluation of in vitro anti-inflammatory activity. Ind. Crops Prod. 188, 115540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115540 (2022).

Jiyauddin, K. et al. Formulation of clindamycin nano-emulsion. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 6 (5), 1845–1854. https://doi.org/10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.6 (2015).

Sharma, N. et al. A new concept of delivery system. Chronicles Young Sci. 1, 2–6 (2010).

Barradas, T. N. & de Silva, H. Nanoemulsions of essential oils to improve solubility, stability and permeability: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 19 (2), 1153–1171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-020-01142-2 (2021).

Odriozola-Serrano, I., Oms-Oliu, G. & Martín-Belloso, O. Nanoemulsion-based delivery systems to improve functionality of lipophilic components. Front. Nutr. 1, 24. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2014.00024 (2014).

Trifan, A. et al. Recent advances in tackling microbial multidrug resistance with essential oils: combinatorial and nano-based strategies. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 46, 338–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/1040841X.2020.1782339 (2020).

Zhou, Y., Kong, Y., Kundu, S., Cirillo, J. D. & Liang, H. Antibacterial activities of gold and silver nanoparticles against Escherichia coli and bacillus Calmette-Guérin. J. Nanobiotechnol. 10, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-3155-10-19 (2012).

Alvand, Z. M., Parseghian, L., Aliahmadi, A., Rahimi, M. & Rafati, H. Nanoencapsulated Thymus daenensis and Mentha Piperita essential oil for bacterial and biofilm eradication using microfluidic technology. Int. J. Pharm. 651, 123751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2023.123751 (2024).

Ghomashi, S. et al. Evaluation of antibacterial, cytotoxicity, and apoptosis activity of novel chromene-sulfonamide hybrids synthesized under solvent-free conditions and 3D-QSAR modeling studies. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 12878 (2024).

Siripatrawan, U. Active food packaging from Chitosan incorporated with plant polyphenols. Nov Approach. Nanotechnol. Food 1, 465–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804308-0.00014-5 (2016).

Cui, H., Yuan, L., Li, W. & Lin, L. Edible film incorporated with chitosan and Artemisia annua oil nanoliposomes for inactivation of Escherichia coli O157: H7 on cherry tomato. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 52, 687–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijfs.13322 (2017).

Pongsumpun, P., Iwamoto, S. & Siripatrawan, U. Response surface methodology for optimization of cinnamon essential oil nanoemulsion with improved stability and antifungal activity. Ultrason. Sonochem. 60, 104604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.05.021 (2020).

Koocheki, A. & Kadkhodaee, R. Effect of Alyssum homolocarpum seed gum, tween 80 and NaCl on droplets characteristics, flow properties and physical stability of ultrasonically prepared corn oil-in-water emulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 25, 1149–1157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2010.10.012 (2011).

Chuesiang, P., Siripatrawan, U., Sanguandeekul, R., McLandsborough, L. & McClements, D. J. Optimization of cinnamon oil nanoemulsions using phase inversion temperature method: impact of oil phase composition and surfactant concentration. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 514, 208–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2017.11.084 (2018).

Gallagher, P. A. & Danielson, N. D. Colorimetric determination of macrolide antibiotics using ferric ion. Talanta 42 (10), 1425–1432. https://doi.org/10.1016/0039-9140(95)98348-J (1995).

Klaus, A. et al. Effect of salts on the phase behavior and the stability of nano-emulsions with rapeseed oil and an extended surfactant. Langmuir 28 (22), 8318–8328. https://doi.org/10.1021/la300435t (2012).

Vickers, N. J. Animal communication: when I’m calling you, will you answer too? Curr. Biol. 27, R713–R715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.05.064 (2017).

Prakash, B. et al. Nanoencapsulation: an efficient technology to boost the antimicrobial potential of plant essential oils in food system. Food Control 89, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.01.018 (2018).

Ahmed, S., Gull, A., Alam, M., Aqil, M. & Sultana, Y. Ultrasonically tailored, chemically engineered and QbD enabled fabrication of agomelatine nanoemulsion; optimization, characterization, ex-vivo permeation and stability study. Ultrason. Sonochem. 41, 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.09.042 (2018).

Chen, Q. et al. Effect of cellulose nanocrystals-loaded ginger essential oil emulsions on the physicochemical properties of mung bean starch composite film. Ind. Crop Prod. 191, 116003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.116003 (2023).

Falcao, M. A. et al. Determination of antibacterial activity of vacuum distillation fractions of lemongrass essential oil. Phytochem. Rev. 11, 405–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11101-012-9255-3 (2012).

Ahmed, B., Hashmi, A., Khan, M. S. & Musarrat, J. ROS mediated destruction of cell membrane, growth and biofilms of human bacterial pathogens by stable metallic AgNPs functionalized from bell pepper extract and quercetin. Adv. Powder Technol. 29, 1601–1616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apt.2018.03.025 (2018).

Long, Y., Huang, W., Wang, Q. & Yang, G. Green synthesis of garlic oil nanoemulsion using ultrasonication technique and its mechanism of antifungal action against Penicillium italicum. Ultrason. Sonochem. 64, 104970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.104970 (2020).

Guo, M. et al. Synergistic antibacterial effects of ultrasound and thyme essential oils nanoemulsion against Escherichia coli O157: H7. Ultrason. Sonochem. 66, 104988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.104988 (2020).

Munekata, P. E. S. et al. The role of essential oils against pathogenic Escherichia coli in food products. Microorganisms 8, 924. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8060924 (2020).

Oussalah, M., Caillet, S. & Lacroix, M. Mechanism of action of Spanish oregano, Chinese cinnamon, and savory essential oils against cell membranes and walls of Escherichia coli O157: H7 and Listeria monocytogenes. J. Food Prot. 69, 1046–1055. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X-69.5.1046 (2006).

Bhargava, K., Conti, D. S., da Rocha, S. R. P. & Zhang, Y. Application of an oregano oil nanoemulsion to the control of foodborne bacteria on fresh lettuce. Food Microbiol. 47, 69–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fm.2014.11.007 (2015).

Alves, D. S., Pérez-Fons, L., Estepa, A. & Micol, V. Membrane-related effects underlying the biological activity of the anthraquinones emodin and barbaloin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 68, 549–561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2004.04.012 (2004).

Moravej, H. et al. Antimicrobial peptides: features, action, and their resistance mechanisms in bacteria. Microb. Drug Resist. 24, 747–767. https://doi.org/10.1089/mdr.2017.0392 (2018).

Khanna, K. et al. Enthralling the impact of engineered nanoparticles on soil microbiome: a concentric approach towards environmental risks and cogitation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 222, 112459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112459 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by Nik Sina Darou company and Shahid Beheshti University Research Council and MPDR.

Funding

The works experiments funding was supported by of Nik Sina Darou company and Research council Shahid Beheshti university.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z. M.A: Investigation, Writing—original draft, Re-sources. M.R.: Validation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing—review & editing. L.P: Investigation, Visualization, Formal analysis. F.H.: Investigation, Visualization H.R.: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing—review & editing, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moradi Alvand, Z., Rahimi, M., Parseghian, L. et al. Application of microfluidic technology and nanoencapsulation to amplify the antibacterial activity of clindamycin against a food born pathogen. Sci Rep 15, 5334 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89955-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89955-5