Abstract

Deep reinforcement learning has been widely applied to solve the anti-jamming problems in wireless communications, achieving good results. However, most research assumes that the communication system can obtain complete Channel State Information (CSI). Under limited CSI conditions, this paper models the system using Partially Observable Markov Decision Processes (POMDPs). In addition, it is challenging to determine the optimal exploration rate decay factor for decision algorithms using exponential decay exploration rate. This paper proposes an exploration rate decay factor automatic adjustment algorithm. Additionally, a Deep Recurrent Q-Network (DRQN) algorithm architecture suitable for the scenario is designed, along with an intelligent anti-jamming decision algorithm. The algorithm first uses Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks to learn the temporal features of input data, flattens the features, and then feeds the result into fully connected layers to get the intelligent anti-jamming strategy. Simulation results demonstrate that the exploration rate decay factor automatic adjustment algorithm can achieve nearly optimal performance when set with a large initial exploration rate decay factor. Under periodic jamming and intelligent blocking jamming, the proposed algorithm reduces the number of time slots required for convergence by 45% and 32% compared to the performance-optimal Double DQN (DDQN) algorithm in comparison algorithms. The normalized throughput after convergence is slightly higher, and the convergence performance is significantly better than that of Deep Q-Network (DQN) and Q-Learning (QL).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to the open and easily accessible nature of electromagnetic wave propagation media, unauthorized and malicious users have made the electromagnetic spectrum environment more complex. This has significantly impacted the reliability and effectiveness of wireless communication transmission. Therefore, wireless communication systems need to adopt various anti-jamming techniques to eliminate or reduce the impact of various artificial jamming, especially malicious jamming1. Traditional communication anti-jamming techniques rely on spread spectrum technology, which can greatly enhance the ability to resist conventional jamming2. However, due to the lack of adaptability to time-varying jamming environments, spread spectrum technology struggles to counter dynamic jamming3.

Currently, there have been research efforts applying artificial intelligence concepts and related algorithms to the field of intelligent communication anti-jamming. Zhou et al.4 proposes a time-domain anti-pulse jamming algorithm based on reinforcement learning, which effectively reduces jamming collision rates and significantly improves normalized throughput. Chen et al.5 introduces an anti-jamming decision method based on QL, which maintains high spectrum efficiency under jamming attacks. Li et al.6 presents a communication frequency and power selection algorithm based on deep reinforcement learning, capable of achieving high throughput. These algorithms assume that the communication system can obtain complete CSI and thus utilize Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) for problem modeling.

However, since the tunable channel bandwidth of some radio frequency receivers is limited to a few tens of megahertz, these systems cannot acquire complete CSI. Therefore, it is necessary to research intelligent communication anti-jamming algorithms that can adapt to partial CSI. Currently, POMDP models, which are more in line with real-world scenarios, have been widely used for modeling in various fields7,8. To solve the POMDP models, DRQN algorithm architecture was first introduced in the work of Hausknecht et al.9, adding LSTM to the conventional DQN to extract features from historical time series data and resolve the dependency on fully sensing the environment. LSTM is a special type of recurrent neural network that was first introduced to address the issues of exploding and vanishing gradients10. It was later enhanced with a forget gate to prevent the problem of unbounded internal state growth11, leading to better performance in handling long sequence data12. Subsequently, some research studies deeper and apply DRQN in partially observable models13,14,15.

Recently, neural network architectures such as LSTM and attention mechanisms have been more widely applied in sequential decision-making because these models can effectively handle sequential data. The attention mechanism is particularly suited for fields like natural language processing and computer vision, while LSTM is better at managing the temporal dependencies of sequential data. To address the issue of limited CSI, this paper also models the environment as a POMDP model and designs a suitable DRQN algorithm architecture with an intelligent anti-jamming decision algorithm as the solution method. This allows agents to more effectively utilize information and find optimal strategies more quickly. In addition, setting the exploration rate in the greedy strategy to decay exponentially is a common practice in decision algorithms, which involves a parameter that affects the rate of exploration rate decay. In this paper, this parameter is referred to as the exploration rate decay factor. To address the issue of being unable to determine the optimal exploration rate decay factor in unknown environments, this paper proposes a self-adjusting exploration rate decay factor algorithm based on predetermined performance conditions. This enables the decision algorithm to achieve near-optimal performance even when initially set with a higher exploration rate decay factor.

System model and problem formulation

System model

The system model studied in this paper is illustrated in Fig. 1. In the wireless communication system under study, there is a pair of transmitter and receiver, hereinafter referred to as the “system.”

The receiver is within the jamming range of an external malicious jammer. For the convenience of research, the following assumptions are made in this paper:

The available frequency bands for wireless communication consist of N adjacent channels in the frequency domain, each with a non-overlapping bandwidth of B and centered at frequency \(\{ {f_1},{f_2},.,{f_N}\}\). The transmitter is not within the effective jamming range of the malicious jammer and can reliably receive control information from a low-capacity feedback channel strengthened by the protocol16. In a discrete-time model, communication time is divided into multiple timeslots of length \({T_s}\). A timeslot is the smallest unit of time for continuous data transmission, the system can communicate in this wireless communication frequency band by changing communication channels in timeslots. In each timeslot, the system can simultaneously sense a contiguous group of M channels. The set of sensed channels can be represented as \({\mathbf{F}}_{t}^{p}=\{ f_{1}^{p},f_{2}^{p},.,f_{M}^{p}\} ,\;M<N\), where \(f_{m}^{p},\;m \in \{ 1,.,M\}\) represents the mth sensed channel. Based on the sensing results, estimate the current state of all channels and select communication channel \(F_{t}^{c} \in \{ {f_1},{f_2},.,{f_N}\}\). The channel chosen for communication is not necessarily a subset of the sensed channels.

Problem formulation

In this paper, a POMDP is used to model the above wireless communication anti-jamming scenario. The state space contains all possible true states of the target frequency band. The true state of channel n in timeslot t is defined as the instantaneous received power of the communication signal

in that timeslot, and can be represented as:

where: pt is the transmit power of the transmitter. gt is the transmission channel gain, assuming a block fading transmission channel model17, where the channel gain remains constant within the same timeslot and varies between timeslots. \(\delta (x)\) is an indicator function such that \(\delta (x)=1\) when x is true, and \(\delta (x)=0\) otherwise. \({\bar {P}_{n,t}}\) is the average jamming plus noise power received.

In timeslot t, the true state of the entire target frequency band can be represented as:

The transmitting power of the communication transmitter is constant. In timeslot t, the action at of the system is to select one channel among N channels for communication.

The state transition function is used to represent the probability distribution of the next state given the state st and action at of the target frequency band. The probability of transitioning to a certain state st+1 can be calculated as:

The reward function is used to calculate the immediate reward r(st,at). The immediate reward is measured using normalized throughput, where normalized throughput is defined as:

where: \({\theta _{th}}\) is the receiver’s Signal to Jamming plus Noise Ratio (SJNR) demodulation threshold. \({\theta _t}\) is the average SJNR received by the receiver. The normalized throughput performance of decision algorithms in the timeslots from t1 to t2 is evaluated using the average normalized throughput:

The receiver can utilize a wideband spectrum sensing technique similar to the one described in the work of Mughal et al.18 to determine the presence of jamming signals in the channel by extracting signal features. The sensing result for a single channel can be classified into two categories: presence of jamming and absence of jamming.

The sense function represents the probability that the system transitions to state st+1 in the target frequency band with sensing result zt after taking at.

In the modeling of partially sensible problems in this paper, the system can accurately sense the jamming conditions of the channels, but it can only sense a subset of the channels at the same time. Therefore, the system cannot rely on sensing results to determine the true states of the target frequency band. In partially sensible scenarios, belief states are commonly used to measure the state of the environment19. The belief state represents the probability distribution of each state of the target frequency band at a certain timeslot. The belief state is updated using Bayesian criterion:

where

Defining the action selection policy as \(\pi :{\mathbf{b}} \to a\), solving the POMDP involves finding the optimal action selection policy \({\pi ^*}:{{\mathbf{b}}^*} \to {a^*}\) that maximizes the expected discounted reward for each belief state. This maximum expected discounted reward can be obtained through the following value function:

Three equations above all contain state transition functions, and under the premise of no prior knowledge, the system cannot know the state transition functions. Even if the current belief state is calculated based on sensing results, the belief state cannot be updated using the Bayesian criterion. Therefore, this paper uses deep reinforcement learning to solve the POMDP model, continuously optimizing the neural network during the interaction with the environment to fit the mapping between the historical sense-action pairs sequence and communication system decisions. This approach effectively learns the optimal communication anti-jamming strategy.

Algorithm

Timeslot structure

In communication anti-jamming scenarios, spectrum sensing requires some time to obtain the jamming status of the target frequency band in the current timeslot. Subsequently, the sensing results are input into the algorithm to make decisions, which are then executed. In the traditional serial timeslot structure20,21, spectrum sensing, learning, and decision-making inevitably occupy a portion of the data transmission time, leading to low slot utilization rates22.

Since the receiver can delegate spectrum sensing, data transmission, and algorithm learning and decision-making to different modules, and utilize an experience pool to keep the algorithm in a learning state during system spectrum sensing. The agent makes decisions based on the sensing results of the current timeslot, which are then executed in the next timeslot. Therefore, the algorithm presented in this paper can parallelly complete spectrum sensing, learning, decision-making, and data transmission in each timeslot, as shown in Fig. 2.

LSTM module

The internal structure of an LSTM unit is depicted in Fig. 3, where \(\sigma\) represents the Sigmoid activation function and tanh represents the hyperbolic tangent function.

The input/output relationship of LSTM is:

In the equation, \({{\varvec{C}}_{t - 1}}\) and \({{\varvec{h}}_{t - 1}}\) respectively represent the memory state and output of the LSTM unit at time step \(t - 1\); \({x_t}\) represents the input of the LSTM unit at time step t; \({f_t}\), \({i_t}\), and \({o_t}\) represent the forget gate, input gate, and output gate of the LSTM unit at time step t; W and b represent the weight matrix and bias terms. LSTM uses the forget gate to determine the extent to which the long-term memory information from the previous time step is retained; the input gate controls the input information at the current time step to prevent irrelevant information from being input; and the output gate determines which useful information needs to be output.

The algorithm for automatically adjusting the exploration rate decay factor

Decision algorithms often use the \(\varepsilon\)-greedy method to balance exploration and exploitation, where the exploration rate \(\varepsilon\) represents the probability of selecting a random action in the decision algorithm23. The exploration rate should be sufficiently high in the early stages to explore more and to some extent avoid the decision algorithm getting stuck in local optima. Once the decision algorithm has learned a good strategy, a lower exploration rate should be used to obtain more rewards. Therefore, a fixed exploration rate cannot satisfy both sufficient exploration in the early stages and sufficient exploitation in the later stages24. Exponential decay of the exploration rate is a better way to dynamically compute \(\varepsilon\), as shown in the following equation:

where, t denotes the number of timeslots; \({\varepsilon _{start}}\) represents the initial exploration rate; \({\varepsilon _{end}}\) is the final exploration rate; \({\varepsilon _{decay}}\) is the exploration rate decay factor. Usually, \({\varepsilon _{start}}\) can be set to 1 to ensure sufficient early exploration. The final exploration rate can be set to 0.001 to ensure sufficient utilization. \({\varepsilon _{decay}}\) is the key to adjusting the decay speed, but in general, decision algorithms cannot confirm how the exploration rate decay factor should be set when they are first used due to the unknown jamming. Setting it too low can easily lead to a lack of exploration by the decision algorithm, while setting it too high may limit the full utilization of the decision algorithm after obtaining a good strategy. Therefore, this paper proposes an exploration rate decay factor automatic adjustment algorithm, which can be invoked in decision algorithms.

Algorithm 1 sets two performance conditions based on the terciles between the average normalized throughput obtained through random exploration during the initial accumulation of samples and the target normalized throughput. The main idea is to treat the performance of random exploration as the performance before training the decision algorithm, and the target performance as the performance after the decision algorithm has converged. At this point, the two points represent two milestones in the period from the beginning of training to the convergence of the decision algorithm. Considering the large state-action space of the decision algorithm, this paper defines 600 timeslots as one episode. Algorithm 1 needs to receive the time slot number, immediate reward, and a flag indicating whether the action is for exploration or exploitation. Thus, algorithm 1 can calculate the average normalized throughput obtained using the learned policy in each episode. If the average normalized throughput obtained by utilizing the learned policy in a certain episode meets a certain performance condition, it indicates that the decision algorithm has learned a good policy. The exploration rate decay factor can be adjusted based on the predetermined exploration rate corresponding to this performance condition. The predetermined exploration rates for the two performance conditions ensure a balance between exploiting the learned policy effectively and retaining exploration probability, with a lower predetermined exploration rate for higher performance conditions. By applying algorithm 1, the decision algorithm can set a relatively high initial exploration rate decay factor in an unknown environment and automatically adjust the exploration rate decay factor upon meeting the predetermined performance conditions to achieve better normalized throughput performance.

Wireless communication intelligent anti-jamming decision algorithm

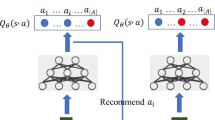

This paper has designed a DRQN algorithm architecture suitable for the scenario in this paper, which adopts the classical architecture of conventional DQN but mainly modifies the internal network structures of the main Q-network and the target Q-network. The algorithm architecture is shown in Fig. 4.

Each Q-network consists of an LSTM layer and two fully connected layers, the main Q-network has two types of inputs and outputs, corresponding to the decision-making and learning processes. A masking mechanism is used to handle missing values in the sensing results by labeling channels with jamming as “0” and channels without jamming as “1”, while channels that were not sensed are uniformly labeled as “2”. During the learning process, the LSTM layer automatically ignores inputs labeled “2”. The sense-action pairs of historical consecutive seq_len timeslots are represented as:

The main Q-network outputs \(Q({\phi _i},{a_{i+1}};\varvec{\theta})\), and the target Q-network outputs \({\hbox{max} _a}\hat {Q}({\phi _{i+2}},a;{\varvec{\theta}^ - })\)25. The loss function is then calculated according to the following equation and the main Q-network weight parameters are updated using stochastic gradient descent and backpropagation26.

In the equation, the weight parameters set of the target Q-network is updated every K steps to match the weight parameters set of the main Q-network. \({\gamma _L}\) is the discount factor used to measure the emphasis placed on the target Q values.

If the input is used for decision-making, only the main Q-network is used, and its output determines the decision as follows:

The process of the wireless communication intelligent anti-jamming decision algorithm based on the above DRQN algorithm architecture proposed in this paper is as show in algorithm 2.

This article uses Floating Point Operations (FLOPs) to measure the computational complexity of the proposed algorithm for a single forward propagation. The computation of a fully connected layer can be viewed as the multiplication of two matrices, with its complexity expressed as \(2IOL\), where I represents the input dimension, O represents the output dimension and L represents the \(seq\_len\). The LSTM layer includes input gate, forget gate, cell state, and output gate, which involve four matrix multiplications, along with the activation function calls, resulting in a computational complexity expressed as \(8L(O(I+O)+O)\). The proposed algorithm in this article replaces the first fully connected layer of the DQN algorithm with an LSTM layer, thus focusing on the differences in computational complexity of the first layer of the network. The FLOPs of the LSTM layer is \(4(I+O+1)/I\) times that of the fully connected layer.

Simulation settings and results

Simulation settings

The algorithm in this paper is implemented based on PyTorch for simulation. Specifically, we first build the interactive environment of the transmitter and jammer in PyTorch, as described in the system model section. Next, we implement the proposed algorithm and embed it into the decision-making process of the transmitter. The transmitter’s interaction data is synchronized for algorithm training and includes perception results, actions, and reward values. The simulation considers the following two typical dynamic jamming styles, as shown in Fig. 5.

Periodic jamming: Each timeslot jams with 20 channels, and the jamming consists of two sections of partial band jamming covering 10 channels each, and the two sections of partial band blocking jamming do not overlap each other. The first 11 timeslots form the first cycle, and the jamming is randomly switched at the end of each timeslot. Starting from the 12th timeslot, the jamming of the first 11 timeslots is continuously repeated.

Time-frequency diagram of two kinds of jamming: (a) Periodic jamming; (b) Intelligent blocking jamming. The two images use gray and blue squares to represent the channel occupancy of jamming and communication behavior in each time slot, respectively. If the communication channel required by the user is jammed with, it is indicated by a red square.

Intelligent blocking jamming: The jammer changes the jamming channel every 5 timeslots to the channel occupied by the communication signal in the past 5 timeslots and its four nearby channels, and the jamming remains unchanged between two changes.

The simulation will demonstrate the impact of different exploration rate decay factors on the performance of the decision algorithm. Comparing the normalized throughput performance of applying the same decision algorithm with ERDFAA algorithm and conventional exponential decay exploration rate. The proposed WCIADA algorithm will be compared with QL algorithm27, DQN algorithm28, and DDQN algorithm29 in terms of normalized throughput performance. To objectively analyze the performance of the proposed algorithm, the parameters of the comparative algorithms are set to the same values as the proposed algorithm. The maximum capacity of the replay memory pool is 10,000, and the batch size is 64. Other major parameter settings are as shown in Table 1.

The system utilizes wideband spectrum sensing technology to sense 10 consecutive channels in each timeslot. The 50 channels are divided into 5 groups of non-overlapping channels, with each group containing 10 channels. The sense strategy is to sequentially sense Group 1 to Group 5, then cycle back to Group 1 and repeat the process.

Simulation results

Employing the exponential decay exploration rate as shown in Eq. (11) can balance the early exploration and later exploitation of the decision algorithm. Figure 6 in this paper illustrates the normalized throughput performance and exploration rate change curve of WCIADA algorithm utilizing the exponential decay exploration rate, with periodic jamming where every 600 timeslots form an episode. As shown in Fig. 6(a), the same decision algorithm exhibits significant differences in normalized throughput performance due to variations in the exploration rate decay factor. Performance is similar when the exploration rate decay factors are set to 500 and 1000, and the performance decreases more noticeably with larger exploration rate decay factors. Combining the exploration rate change curve in Fig. 6(b), it can be observed that at \({\varepsilon _{decay}} \leqslant 1000\), the decision algorithm has already achieved good exploration and exploitation. However, at \({\varepsilon _{decay}}>1000\), the convergence of normalized throughput performance is limited by the exploration rate.

Based on the above discussion, although using the conventional exponential decay exploration rate can help the decision algorithms balance exploration and exploitation, it requires setting the appropriate exploration rate decay factor. However, the decision algorithm in this paper needs to

deal with unknown and dynamic electromagnetic environments, where different levels of exploration are needed in different electromagnetic environments. It is not possible to determine the appropriate exploration rate decay factor through comparative experiments. By applying ERDFAA algorithm, a relatively large initial exploration rate decay factor can be set, and the exploration rate decay factor can be automatically adjusted when certain predetermined conditions are met. Figure 7 compares ERDFAA algorithm and conventional exponential decay exploration rates. When ERDFAA algorithm is applied, the initial \({\varepsilon _{decay}}\) is set to 5000, while when conventional exponential decay exploration rates are applied, the \({\varepsilon _{decay}}\) is set to 1000 and 5000 respectively. As shown in the figure, in the first three episodes, the normalized throughput performance of the two exploration rate algorithms is similar. When the automatic adjustment condition is triggered in the third episode, the exploration rate sharply decreases, leading to a significant increase in normalized throughput performance. According to the conclusion of Fig. 6, the performance of WCIADA algorithm at \({\varepsilon _{decay}}=1000\) is close to optimal. Originally, there was a significant gap in performance at \({\varepsilon _{decay}}=5000\), but by applying ERDFAA algorithm, it almost achieved the optimal performance. Therefore, in subsequent simulations, both WCIADA algorithm and the comparative algorithm adopt ERDFAA algorithm to automatically adjust the exploration rate decay factor.

The LSTM layer has two outputs, one is the output \({{\varvec{h}}_t}\) at the last time step, and the other is \(output\) that contains all time step outputs. Currently, there are many articles have investigated the applications of LSTMs in decision problems, but few have studied in which situations using which output of the LSTM would make the algorithm perform better30,31,32. Therefore, this paper compares and conducts simulation experiments under periodic jamming. The performance is shown in Fig. 8. In the communication anti-jamming scenario of this paper, flattening the output \(output\) of the

LSTM layer and feeding it into the fully connected layer can make the decision algorithm converge faster. Therefore, in subsequent simulations, WCIADA algorithm uses \(output\) for decision-making.

In addition, the \(seq\_len\) is an important parameter that affects the performance of the algorithm. As shown in Fig. 9, under periodic jamming, when \(seq\_len=2\), the algorithm converges slowly and the reaches a low convergence value. When \(seq\_len=6\), it can be seen from the local magnification diagram that the algorithm converges slightly slower than that when \(seq\_len=10\).

When \(seq\_len>10\), the normalized throughput performance does not continue to improve. Therefore, in subsequent simulations, \(seq\_len\) is set to 10.

In the contrast algorithm, the QL algorithm requires maintaining a Q-table, which records and updates the Q-values for each action taken under each state. In the scenario of this paper, if the same input is used as WCIADA algorithm, the number of states reaches \(55 \times {50^{10}}\), and it is even larger under intelligent blocking jamming. In a problem with such a high-dimensional state space, the performance of the QL algorithm will be poor, even performing worse than only inputting the sense-action pair of the previous timeslot, as shown in the performance comparison under periodic jamming in Fig. 10(a). The DQN algorithm uses a neural network to approximate the Q function instead of storing a huge Q-table, allowing DQN to handle problems with high-dimensional state spaces. The performance of DQN also undergoes simulation comparison, as shown in Fig. 10(b). Since DDQN only optimizes the use of two networks in DQN to address the issue of overestimating Q-values33, it can also handle problems with high-dimensional state spaces, hence no additional discussion is needed here. Therefore, in the subsequent comparison with WCIADA algorithm, the QL algorithm inputs only the sense-action pair of the previous timeslot, while DQN and DDQN algorithms, like WCIADA algorithm, input historical continuous ten timeslots of sense-action pairs.

Figure 11 displays the performance comparison under periodic jamming and intelligent blocking jamming for WCIADA algorithm and three other comparison algorithms. From the figure, it can be observed that WCIADA algorithm converges the fastest, achieves the highest convergence value, and exhibits the most stability under both types of jamming. Under the simpler periodic jamming, WCIADA algorithm first achieves a normalized throughput performance of 1 in the 12th episode and gradually converges. The average normalized throughput over the last forty episodes is approximately 0.9998, with a variance of \(\:4.54\times\:{10}^{-7}\). In comparison, the best-performing DDQN algorithm among the comparison algorithms reaches a normalized throughput performance of above 0.99 by the 22nd episode. The average performance of DDQN over the last forty episodes is approximately 0.9923, with a variance of \(\:7.09\times\:{10}^{-6}\). The performance of the DQN algorithm is slightly inferior to the DDQN algorithm, while the QL algorithm performs the worst, converging to around 0.9623 by the 70th episode. Under intelligent blocking jamming, the performance gap between the algorithms widens. WCIADA algorithm achieves a normalized throughput performance of above 0.99 with fluctuations by the 10th episode, reaching 1 by the 29th episode and gradually stabilizing. The average performance of the WCIADA algorithm over the last forty episodes is approximately 0.9997, with a variance of \(\:1.69\times\:{10}^{-6}\). The DDQN algorithm slightly outperforms the DQN algorithm, reaching above 0.99 by the 43rd episode. The average performance of the DDQN algorithm over the last forty episodes is 0.99, with a variance of \(\:2.39\times\:{10}^{-5}\). The QL algorithm performs the worst, as even with inputting only the sense-action pair of the previous timeslot, the state space remains large. Additionally, due to the changes in intelligent blocking jamming every 5 timeslots, the learning speed of the QL algorithm is significantly hindered.

Conclusions

This paper discusses modeling the communication anti-jamming process under limited CSI as a POMDP model. To address the challenge of determining the exploration rate decay factor in decision algorithm in unknown environments, a self-adjusting algorithm based on predetermined performance conditions is proposed. This algorithm can achieve near-optimal performance even when the initial exploration rate decay factor is set to a large value. Furthermore, the paper conducts comparative experiments on the impact of certain key factors in the DRQN algorithm architecture on performance. It also designs a suitable DRQN algorithm architecture to facilitate intelligent anti-jamming decision in wireless communication scenarios. Simulation experiments show that compared to three other algorithms, the proposed WCIADA algorithm converges faster, reaches a higher convergence value. The algorithm proposed in this article also has the potential for application in more channels and more complex jamming scenarios, but it will face increased computational complexity. In our future research, we will pay more attention to controlling the computational complexity of the algorithm while addressing anti-jamming issues.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Pirayesh, H. & Zeng, H. Jamming attacks and anti-jamming strategies in wireless networks: a comprehensive survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tut. 24, 767–809 (2022).

Yao, F. Communication Anti-jamming Engineering and Practice (2012).

Zhu, Y. & Zhang, J. Interference task allocation algorithm of multiple jammers based on reinforcement learning. Audio Eng. 47, 141–145 (2023).

Zhou, Q., Li, Y. & Niu, Y. A countermeasure against random pulse jamming in time domain based on reinforcement learning. IEEE Access. 8, 97164–97174 (2020).

Chen, C., Song, M., Xin, C. & Backens, J. A game-theoretical anti-jamming scheme for cognitive radio networks. IEEE Netw. 27, 22–27 (2013).

Li, Y., Xu, Y., Wang, X., Li, W. & Bai, W. Power and frequency selection optimization in anti-jamming communication: a deep reinforcement learning approach. In IEEE 5th International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC) 815–820 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCC47050.2019.9064174 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Cooperative data collection with multiple UAVs for information freshness in the internet of things. IEEE Trans. Commun. 71, 2740–2755 (2023).

Che, Y. L., Zhang, R. & Gong, Y. On design of opportunistic spectrum access in the presence of reactive primary users. IEEE Trans. Commun. 61, 2678–2691 (2013).

Hausknecht, M. & Stone, P. Deep recurrent Q-learning for partially observable MDPs. Preprint at (2015). https://arxiv.org/abs/1507.06527.

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9, 1735–1780 (1997).

Gers, F. A., Schmidhuber, J. & Cummins, F. Learning to forget: continual prediction with LSTM. In Ninth International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks ICANN 99 (Conf. Publ. No. 470) 850–855 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1049/cp:19991218 (1999).

Lee, S., Kim, S., Seo, M. & Har, D. Synchronization of frequency hopping by LSTM network for satellite communication system. IEEE Commun. Le. 23, 2054–2058 (2019).

Moreno-Vera, F. Performing deep recurrent double Q-learning for Atari games. In 2019 IEEE Latin American Conference on Computational Intelligence (LA-CCI) 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/LA-CCI47412.2019.9036763 (2019).

Gao, N., Qin, Z., Jing, X., Ni, Q. & Jin, S. Anti-intelligent UAV jamming strategy via deep Q-networks. IEEE Trans. Commun. 68, 569–581 (2020).

Ruan, X., Li, P., Zhu, X. & Liu, P. A target-driven visual navigation method based on intrinsic motivation exploration and space topological cognition. Sci. Rep. 12, 3462 (2022).

Zhou, Q., Niu, Y., Xiang, W. & Zhao, L. A. Novel reinforcement learning Algorithm based on broad learning system for fast communication antijamming. IEEE Trans. Industr Inf. (2024).

Sun, Y., Li, B., Liang, C. & Li, Y. Design of serial connecting multiple spatially coupled LDPC codes for block-fading channels. J. Xidian Univ. 46, 1–5 (2019).

Mughal, M. O., Nawaz, T., Marcenaro, L. & Regazzoni, C. S. Cyclostationary-based jammer detection algorithm for wide-band radios using compressed sensing. In IEEE Global Conference on Signal and Information Processing (GlobalSIP) 280–284. https://doi.org/10.1109/GlobalSIP.2015.7418201 (2015).

Liu, J., Zhang, R., Gong, A. & Chen, H. Optimizing age of information in wireless uplink networks with partial observations. IEEE Trans. Commun. 71, 4105–4118 (2023).

Liu, S. et al. Pattern-aware intelligent anti-jamming communication: a sequential deep reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Access. 7, 169204–169216 (2019).

Yao, F. & Jia, L. A collaborative multi-agent reinforcement learning anti-jamming algorithm in wireless networks. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Le. 8, 1024–1027 (2019).

Niu, Y., Zhou, Z., Pu, Z. & Wan, B. Anti-jamming communication using slotted cross q learning. Electronics 12, 2879 (2023).

Pu, Z., Niu, Y. & Zhang, G. A multi-parameter intelligent communication anti-jamming method based on three-dimensional Q-learning. In 2022 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Computer Communication and Artificial Intelligence (CCAI) 205–210. https://doi.org/10.1109/CCAI55564.2022.9807745 (2022).

Dos Santos Mignon, A. & De Rocha, A. D. An adaptive implementation of ε-greedy in reinforcement learning. Procedia Comput. Sci. 109, 1146–1151 (2017).

Yen, C. E. et al. An integrated DQN and RF packet routing framework for the V2X network. Electronics 13, 2099 (2024).

Han, G. et al. Deep reinforcement learning for intersection signal control considering pedestrian behavior. Electronics 11, 3519 (2022).

Watkins, C. Learning from delayed rewards. Rob. Auton. Syst. 15, 233–235 (1995).

Cong, J., Li, B., Guo, X. & Zhang, R. Energy management strategy based on deep Q-network in the solar-powered UAV communications system. In IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC Workshops) 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCWorkshops50388.2021.9473509 (2021).

Li, D., Xu, S. & Zhao, J. Partially observable double DQN based IoT scheduling for energy harvesting. In IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC Workshops) 1–6 (2019). (2019). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCW.2019.8756797.

Fan, Y., Tang, Q., Guo, Y. & Wei, Y. BiLSTM-MLAM: a multi-scale time series prediction model for sensor data based on Bi-LSTM and local attention mechanisms. Sensors 24, 3962 (2024).

Jin, Y., Wu, X. & Zhang, J. Intelligent decision making for frequency hopping anti jamming by integrating attention mechanism and LSTM. Radio Commun. Technol. 49, 1059–1066 (2023).

Hung, C. C. et al. Optimizing agent behavior over long time scales by transporting value. Nat. Commun. 10, 5223 (2019).

Hasselt, H. V., Guez, A. & Silver, D. Deep reinforcement learning with double Q-learning. In AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI’16) 2094–2100 (2015). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1509.06461

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their gratitude to National Natural Science Foundation of China for their support throughout this work.

Funding

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (62371461).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.Z. proposed the algorithm and conceived the experiments. Y.N. provided support in the theory of communication anti-jamming. Q.Z. and Q.C. provided support in the theory of deep reinforcement learning.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, F., Niu, Y., Zhou, Q. et al. Intelligent anti-jamming decision algorithm for wireless communication under limited channel state information conditions. Sci Rep 15, 6271 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90201-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90201-1