Abstract

Electronic power converters play an essential role in power grids, aiming to improve the electrical energy quality and also enabling bidirectional energy transfer between DC lines and circuits. They facilitate the achievement of a sinusoidal current waveform and effective power transfer control with a high power factor. This paper introduces a stationary reference frame based control strategy for grid-connected three phase modular multilevel converters (MMC). This strategy employs conventional PI controllers to track the instantaneous power components that include intentional oscillations at double grid frequency. By employing this method, the MMC converter can maintain an output sinusoidal waveform even under unbalanced grid voltage conditions. Also, there is no need for a transformation from a stationary frame to a synchronous frame, eliminating the requirement for a PLL to estimate the grid voltage phase angle. Furthermore, the use of MMC converter over common two-level and three-level VSC converters is proposed since MMC converters offer merits such as low harmonic components, no need for filters at the DC terminals, no need for filters at the AC side, and low losses, despite some drawbacks such as a large number of IGBT switches or a higher amount of stored energy in the sub-module capacitors. Therefore, the voltage THD and consequently active and reactive powers of the converter have been impressively mitigated by using MMC. To confirm the capability and effectiveness of the proposed method, various simulations are performed in MATLAB/Simulink software. Finally, the results are compared with common methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The growing integration of renewable energy sources and smart grids has elevated the importance of efficient and reliable power electronic converters1. Modular Multilevel Converters (MMCs) have emerged as a promising solution due to their inherent advantages, such as reduced harmonic distortion, modular design, and flexibility in grid applications. However, achieving robust control of MMCs under unbalanced and harmonic-distorted grid conditions remains a significant challenge, particularly when conventional methods depend on phase-locked loops (PLLs) and synchronous reference frame transformations. This paper addresses these challenges by proposing a stationary reference frame-based control strategy that eliminates the need for PLLs while maintaining sinusoidal current waveforms and improving harmonic performance.

Electronic power converters play a crucial role in power systems, serving the dual purpose of enhancing the quality of electrical energy and facilitating bi-directional energy transfer between DC lines and circuits2. This versatility finds application in various areas, including electric traction for railway systems, energy storage devices3, active DC link rectifiers or inverters in renewable energy conversion systems4, and so on. These converters enable the achievement of sinusoidal current waveforms and the precise control of power transfer while maintaining a high power factor5,6,7,8. While many three-phase rectifiers implement a diode bridge circuit along with a bulk storage capacitor for their simplicity, robustness9, and cost-effectiveness, they exhibit certain limitations. Diode rectifiers only permit one-way power flow, leading to a low power factor and a high level of harmonic input currents. Consequently, three-phase rectifiers controlled by pulse width modulation (PWM present an appealing alternative, especially in industrial applications. They offer advantages such as bidirectional power transfer and low harmonic distortion in the line current10,11,12,13.

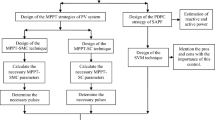

Various control methods are introduced in the research literature to control power electronics, either in rectifier or inverter mode14. Proportional-integral (PI) controllers are one of the most popular control strategies that are implemented to control the components of the current vector in the same direction as the grid voltage vector (VOC) in the dq synchronous reference frame6,7. The d-q transformation is offered in6,7to analyze the three-phase current-controlled PWM rectifier. Here, the dc operational point and ac transformation functions are completely determined. Another popular method is direct power control (DPC), which employs hysteresis controllers and instantaneous components of p and q power8. Determining the phase angle of the grid voltage is required for both strategies. With respect to this issue, more developed methods such as using PLL under the unbalanced grid based on the characteristics of the grid inverter’s instantaneous power response10, virtual flux oriented synchronous reference frame (VFOC) with new optimization strategies to design the best controllers and harmonic compensators with a three-level cascaded control scheme11, or virtual flux based direct power control (VF-DPC) considering an improved sliding mode control (SMC) strategy along with a feedforward current control of the capacitor to eliminate the grid current distortion12, are suggested.

The spatial vector modulation is offered instead of the switching table to achieve a fixed switching frequency for direct power control methods based on space vector modulation (DPC-SVM)13. The implementation of PLL and virtual flux in the control systems can reduce the high order harmonics of the converter’s current caused by the grid voltage harmonics15. Therefore, these methods are still sensitive to grid voltage asymmetry.

A new straightforward control strategy is proposed in16 for controlling the ac input current of voltage based PWM rectifiers which can completely eliminate the steady state control error. This control strategy does not require the instantaneous value of the supply voltage and the exact parameters of the circuit on the ac side of the rectifier. Thus, an effective and powerful operational point can be obtained against the circuit parameter variations.

The synchronous frame controllers generally outperform the stationary frame controllers and are adopted because they operate by using dc values, and thus, can eliminate steady-state errors17. Ref18. establishes a theoretical correlation between these two controllers and introduces a new stationary frame regulator, the P + Resonant regulator, which provides the same transient and steady-state performance as the synchronous frame PI regulator. This new controller can be employed for both single- and three-phase inverters.

The implementation of PI controllers in the stationary frame is inappropriate due to the steady state errors. Conversely, the P + Resonant controllers have steady the state error of zero, though their design is more complicated than a PI controller in a synchronous frame. Consequently, a two-step process is provided in19to design the P + Resonant controller in the optimal stationary reference frame20. The proposed controller includes proportional (P) and resonance (R) regulators in addition to a mutual coupling regulator (X). The PRX controller provides excellent transient and steady-state responses and is derived directly from designing the PI controller in the synchronous framework.

The most direct strategy for adjusting the current of ac converters21is to employ a simple closed-loop based PI controller that, theoretically has no stability limit by increasing the proportional and integral gains, because it is a second-order system. However, PWM modulation and controller sampling delays restrict the gains achieved in practical systems. Considering these limitations, an analytical method is utilized in22 to determine the best possible gain that can be obtained for each class of practical linear ac current controller. The analysis exhibits that the maximum possible proportional gain can be determined by the system series inductance, dc bus voltage, and transmission and sampling delays, while the maximum possible integrator gain can be primarily determined by the transmission and sampling delays.

In23, a stationary frame controller is recommended which is exactly equivalent to the common synchronous frame controller with mutual component decomposition. The new controller in the stationary frame “PRX2” consists of a proportional (P), a resonant (R), and two mutual coupling components. The PRX2 controller presents the same transient and steady-state performance and has the same frequency response as the PI controller in the decomposed synchronous framework. Another simple analysis strategy is to implement the PI controller in the stationary frame to replace the PI controller in the dq synchronous frame, while the coupling components in the dq synchronous frame are neglected, and it is not an accurate approximation. The exact equivalent model of the PI controller is established in the stationary framework. The recommended model can be utilized for the dq synchronous frame controlled system to accurately predict the system performance, and thus, guide the design process of the control parameters24.

The authors of25presented a method for determining the current reference based on extracting the components of the symmetrical sequence of the grid voltage and the converter control signal26, as well as the average values of the instantaneous power components. The main idea is to minimize DC voltage ripple, which leads to asymmetrical current with respect to the asymmetrical voltage in a normal mode because the active component of instantaneous power(p) is not fluctuating in this case. The proposed method is undesirable for the grid in the rectifying mode since this phase is often loaded with the lowest rms voltage value. Similar results are obtained by the authors of27but without extracting the symmetric sequence. In this article, the instantaneous powers of the PWM rectifier are analyzed in the two-phase stationary reference frame. Based on this analysis, input power control and input-output power control strategies are offered for PWM rectifiers under unbalanced voltage conditions in a stationary framework. Compared to the current strategies, the main advantage of this method is its simplicity. The rotating transformation and phase detection of input voltages are both eliminated. In addition, it is not necessary to extract the sequence components of the control variables, which leads to a great reduction of the time delay in the control system28.

The manipulation in the asymmetric current coefficient is introduced in29. The authors presented adaptive parameters with the reference generator, which is based on the decomposition of the symmetrical sequence components of the grid voltage. Unfortunately, the experimental results reveal a highly distorted current. Ref. 25 to 29do not consider the current constraints. Limiting the asymmetric current, this is not an ignorable issue, as its vector representation cannot be converted into the three-phase frame, while it is easily possible for the symmetric current. Therefore, some additional three-phase structures are presented for proper limitation30,31,32.

A reference generator is considered in30that can achieve two goals of maintaining the injected currents in safety values and calculating power references for better utilization of inverter power capacity. The reference generator is quite flexible as the positive and negative active and reactive powers can be injected simultaneously to improve the handling and tolerance of fault occurrence. Ref31. addresses a new three-phase rectifier control scheme that operates under voltage imbalance and grid harmonics simultaneously. The proposed method employs the virtual electromagnetic torque, which is calculated based on the current of the converter and the virtual flux of the power system. The direct calculation of reference current vector \(\:\alpha\:-\beta\:\) components does not require any of the synchronization methods or orientation of the grid voltage/virtual flux of the reference frame.

The control of a three-phase power converter is suggested in32 under grid voltage imbalance. The proposed method adapts the current imbalance with the inverter or rectifier performance. The control goal in the inverter mode is to calculate the non-oscillating p component of the instantaneous power and the \(\:{x}_{v}\) component of the instantaneous virtual torque as the dot product of the grid virtual flux vector and the converter current vector. Then, the phase with lower voltage is supported by the higher current.

Another way to control the performance of grid-connected converters under asymmetric voltage sags is to modify PI current controller based classical structures. Therefore, this adjustment is performed in two synchronous reference frames, which one of them is in the same direction as the positive sequence of the grid voltage, and the other is in the same direction as the negative sequence vector component33,34. Moreover, the dq current negative sequence gap filters are often utilized in these systems34 which narrows the current control bandwidth. A symmetrical current objective is easy to be attained by setting the reference negative sequence current to zero, although it is not entirely beneficial for the grid.

Some modifications in DPC-SVM strategies including considering a virtual flux amplitude based low-pass filter and PLL to synchronize the phase angle of virtual flux are presented in the research literature35. Since the instantaneous power components are independent of the reference frame’s rotation direction, direct power control strategies can be realized without PLL, and it is concurrently possible to synchronize the current of the converter using the grid voltage obtained by its control algorithm, which they have been recently a pivotal research topic5,36,37. Although the control systems presented in5,36are similar, it can be seen in5that the impact of grid voltage harmonics on the current waveform is less. The unbalanced voltage sags are not considered in neither of the above references. Another approach is represented in37, which is the reference power compensation based on the analysis of the current and voltage symmetrical sequences along with the extraction of the third harmonics of the current; the proportional-resonant- integral (PResI) controllers are also utilized for reference tracking. These authors do not consider the grid voltage harmonics. In addition, the results presented here do not show the step change of the average power components, so evaluation of the system dynamics is difficult. The DPC strategy can be assumed without symmetric sequence decomposition, although it is presented in38,39 with a vertical component of the grid voltage vector (with a 90-degree lagging) and requires the precise determination of the grid filter parameters.

A proper asymmetry obtained by the control system for the current can be beneficial for the grid since this phase is loaded with the minimum rms voltage in the rectifier mode and it receives the most support in the inverter mode40. Thus, the converter’s maximum power cannot be delivered, as some arms are operated below their maximum allowed current. A solution to this issue is current balancing when the required power is greater than the value obtained by the asymmetric current limitation. The authors of39 introduced a strategy that allows the asymmetry of the intermediate current between the asymmetry of the grid opposite voltage and the symmetrical current. This approach is only applicable to the grid in the inverter mode. Moreover, the reactive power support is not analyzed.

In41, two types of PWM converters are considered, focusing on their circuit configuration and voltage balance control. The combination of moderate and balanced controllers enables MMCs to balance the voltage without any external circuit. In42, MMCs are implemented in a real HVDC grid in Germany, in which the merits and demerits, as well as the structure and configuration of MMCs on a real scale, are discussed. The model predictive control (MPC) strategy is suggested in43to improve the internal performance of the MMC. In this strategy, a fast MPC is designed to control the exchanged active and reactive powers with the grid-connected MMC, having a quick dynamic response, low THD current, and constant switching frequency. One of the major concerns in half-wave MMCs, especially with a high number of levels, is the occurrence of errors in the converter submodules (SM). Thus, a pulse width modulation strategy with adaptive carrier phase disposition PWM (AC-PDPWM) based fault-tolerant control is offered in44for MMCs with symmetrical and asymmetrical fault tolerance capabilities. The proposed controller adjusts the energy transfer45between the arms, rebalances the SM capacitors, and redistributes the pulses for the SM switches. In high voltage MMCs with the nearest level of modulation (NLM), there is usually high frequency and uncertain switching between the sub-modules of each arm, which is resulted from the common arrangement-based capacitor voltage balance control strategy and causes additional power losses. To solve this problem, the SM switching process and the capacitor voltage sequence of an MMC arm are analyzed in46and a technique is implemented to predict the capacitor voltage convergence in the next cycle. Based on the predicted voltage sequence, an improved capacitor voltage balancing strategy is presented, which can significantly reduce the additional switching losses and improve the operational efficiency of the converter system. In47, a new AC/AC-MMC structure is represented to balance the voltage fluctuations of the large capacitors of MMC drives by changing the speed of the AC motor. The operation principles of this structure are based on a multi-loop feedback control strategy.

Three-phase multilevel inverters are employed for low-power PV applications due to higher power transmission48and better quality of transmitted power. However, the existing structures investigated for these systems are mainly intended for medium and high voltage applications, thus making them less applicable to low voltage systems. As a result, Ref49. illustrates a three-phase multilevel inverter with switch sharing capability and its control solution to overcome this challenge. This method combines the features of a two-level full-wave bridge structure and multi-level structure with a diode clamp. Consequently, the inverter can be utilized at full capacity and the quality of the output power can be significantly improved. A control strategy is also developed capable of maximizing the full potential of the inverter. A PI controller with a new tuning algorithm is designed to effectively deal with load changes as well49. Moreover, a fuzzy logic controller is proposed in50for boost converter regulation of the solar system. Here, a seven-level inverter is implemented to control a three-phase induction motor that is fed through the PV system. The work in51 utilizes sliding mode control (SMC) for direct power control in a unified power quality conditioner (UPQC), targeting the regulation of active and reactive power while compensating for power quality issues like voltage sags, swells, and harmonics. Furthermore, it focuses on achieving robust performance under unbalanced grid conditions. The SMC approach relies on switching control laws to drive the system states to a predefined sliding surface. This provides strong robustness but can introduce chattering effects, which need mitigation.

An advanced SAPF framework incorporating Predictive Direct Power Control to address challenges posed by distorted and unbalanced grid conditions is presented in52. It highlights superior power quality enhancement through reduced harmonics and effective real-time compensation, validated via simulations under non-ideal scenarios. Whereas, the study conducted in53 simplifies the Model Predictive Direct Power Control framework for unbalanced grids, aiming to reduce computational burden while maintaining robust performance. It introduces a steady-state optimization model, enabling effective grid asymmetry handling and enhancing both efficiency and stability.

The multilevel MMC converters have the following merits compared to two-level or three-level VSCs with PWM control41,42, :

-

Generating low harmonics, and thus, less high-frequency noise,

-

No capacitors are required at the DC terminals, resulting in remarkable dynamic behavior,

-

There is no need for a filter at the ac side to avoid any possible interference with the filters installed in the grid.

-

Low losses due to low switching frequency,

-

And, semiconductor components optimization for low conduction losses.

However, there are some disadvantages such as a higher number of IGBT switches or a lot of stored energy in the capacitors of the sub-modules, though the advantages of the MMC design overweigh the disadvantages. An overview of the advantages and disadvantages of the proposed designs of research is provided in Table 1.

This paper presents a novel control system for a three-phase Modular Multilevel Converter (MMC) that leverages a stationary reference frame to regulate voltage and current effectively. The proposed control strategy introduces several advancements compared to conventional methods:

-

1.

Elimination of Rotating Reference Frame Transformations: Unlike traditional approaches that require transformations between stationary and rotating reference frames, this method operates directly in the stationary reference frame. This eliminates the need for additional algorithms such as phase-locked loops (PLLs) to determine the grid voltage phase angle, simplifying the control architecture while maintaining robust performance under unbalanced conditions.

-

2.

PI Controller-Based Instantaneous Power Regulation: The control system employs conventional proportional-integral (PI) controllers to track reference instantaneous power components. By intentionally inducing oscillations at double the grid frequency, the sinusoidal current waveform of the MMC is preserved, even in the presence of negative sequence components in the grid voltage.

-

3.

Dynamic Current Balancing and Power Maximization: The method dynamically adjusts asymmetrical converter currents to suit operational modes and power demands. A power-limiting strategy ensures that phase currents remain within allowable limits, effectively preventing overloading. This approach maximizes the apparent power capability of the MMC while maintaining stable and balanced current profiles.

The proposed control system incorporates the following innovations:

-

Precise Control of Instantaneous Power Fluctuations: Fluctuations caused by asymmetric currents are explicitly determined and managed to maintain a sinusoidal waveform for the converter output.

-

Limitation of Reference Power Components: The system restricts the average values of reference instantaneous power components, ensuring that the maximum amplitude of phase currents does not exceed permissible thresholds.

-

Current Balancing for Optimal Operation: A balancing mechanism maximizes apparent power output while adhering to phase current constraints, particularly in scenarios of asymmetric currents.

The rest of the article is organized as follows: In the second Section, the modeling and configuration of the grid connected MMC converter is presented. Section 3 provides the control method of the MMC converter based on the proposed stationary reference frame. A sample of the MMC converter under rectifier and inverter modes is performed in Sect. 4 in the Simulink environment of MATLAB software and various simulations are conducted to confirm the proposed methodology. Finally, the general conclusion is presented in Sect. 5.

System configuration and modeling

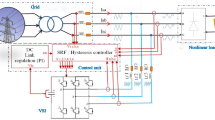

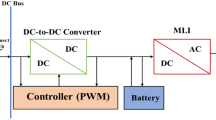

In this configuration, the grid connected MMC converter with consecutive phase shift modulation (CPS-PWM) is implemented according to Fig. 1.

This type of converter is considered because it has some merits over common converters mentioned earlier. The DC side of the MMC converter in inverter mode is a variable DC source that is modeled through a dependent current source. In the rectifier mode, only the direction of current changes in this dependent current source, and thus, behaves as a DC load. On the AC side, the MMC converter is connected to the distribution system through the series impedance, \(\:{R}_{tr}\), and a series filter, \(\:{L}_{tr}\).

Circuit structure of MMC

The circuit diagram of the grid connected MMC converter is demonstrated in Fig. 2. In this structure, an MMC converter with N submodules (SM) is utilized in the upper and lower arms of each phase. The three-phase converter has three arms that are connected to the DC microgrid terminal without using a separate DC link capacitor. A first-order inductive filter, \(\:{\text{L}}_{tr}\), is employed to attenuate high-frequency voltage components. Since the inverter arm connected to phase a is controlled to act as a sinusoidal voltage source, therefore, the main and harmonic components of the grid voltage are indirectly compensated by the system, and a special algorithm is not required to calculate or extract such components. The circuit diagram of the parallel MMC converter is depicted in Figs. 241–44,46,47.

By applying the Kirchhoff voltage law to the upper and lower arms of the ith phase, the relationship between the arm’s current and voltage can be described as Eq. (1).

where \(\:{v}_{1i}(i=a,b,c)\) represnts the voltage of bus 1. \(\:{v}_{pi}\) and\(\:\:{v}_{ni}\) are the voltages of the upper and lower arms, respectively. \(\:{i}_{1i}\) is the grid side current of the parallel converter side. \(\:{i}_{pi}\) and \(\:{i}_{ni}\) are the currents of the upper and lower arms of the phases, respectively. \(\:{v}_{dc}\) is the DC link voltage between the MMC converter and the DC source or load terminal.

Based on the relationship between the grid side current and the arm current (\(\:{i}_{1i}={i}_{pi}+{i}_{ni}\)) and according to relation (1), MMC dynamics can be obtained as:

After simplification, (2) can be rewritten as:

It should be mentioned that each submodule acts as a half-wave inverter, and a parallel capacitor with each SM is responsible for the voltage balance and filtering the output.

Proposed stationary frame based control system

No change between rotating and stationary reference frames eliminates phase angle determination problems associated with grid voltage asymmetry. Therefore, a control system with power controllers is presented in a stationary reference frame. Consequently, it is recommended to utilize the pq instantaneous powers explained by (4) and (5) as control variables.

where\(\:\:{i}_{L\alpha\:}\) and \(\:{i}_{L\beta\:}\) are the converter current vector components, and \(\:{u}_{g\alpha\:}\) and \(\:{u}_{g\beta\:}\)are the grid voltage vector components. The current vector can be expressed as5:

The voltage equations of a three-phase grid connected power converter can be described by instantaneous power components instead of using current:

where \(\:{u}_{c}\) is the converter voltage vector, \(\:{u}_{g}\) is the grid voltage vector, \(\:R\) is the filter resistance, \(\:L\) is the filter inductance, and \(\:p\), \(\:q\) are the instantaneous power components. The derivatives of the current vector components can be described as follows:

where we have:

Notably, the derivative of the total current, and as a result, the voltage drop in the inductor reactance is basically divided into two parts; the former is associated with the instantaneous power components (\(\:{r}_{\alpha\:}\), \(\:{r}_{\beta\:}\)) and the latter corresponds to their derivatives. Considering the voltage and current of the harmonic-free and symmetrical grid, a part of the inductor voltage drop caused by the derivatives of the power components will be zero for the steady state, while \(\:{r}_{\alpha\:}\) and \(\:{r}_{\beta\:}\) are considered for the coupling between p and q. However, when the negative sequence component of the grid voltage is observed, the instantaneous power components must contain certain oscillations of the double grid frequency to maintain the sinusoidal current waveform. Thus, the derivatives of other power components are no longer equal to zero in stable states, and the associated part of the inductor voltage drop is also not equal to zero. In addition, \(\:{r}_{\alpha\:}\) and \(\:{r}_{\beta\:}\) do not only represent the coupling between the power components but also contain a part of them. Both mentioned parts of the inductor voltage drop do not have a sinusoidal waveform, though their sum is sinusoidal, as can be seen in Figure a3. Equations (8) and (9) can be rewritten in the matrix form as:

where we have:

The voltage drop of the inductor converted to the reference frame associated with the power component is directly described by the derivatives of p and q as well as \(\:{r}_{p}\:\)and \(\:{r}_{q}\) which includes the coupling between the power components. Both parts contain dc values along with double grid frequency oscillations, as illustrated in Figure b3. In general, the calculation of \(\:{r}_{p}\:\) and \(\:{r}_{q}\) is not insignificant since it requires differentiating of the measured grid voltage, leading to amplification of measurement noise and other disturbances. However, by considering only the main component harmonic, it can be assumed that:

Example of voltage drop on 2 mH ideal inductor during change of instantaneous power components, for different current targets, \(\:{u}_{g}\)– line voltage (p. u.), \(\:{i}_{L}\) – inductor current (p. u.), \(\:{u}_{L}\) – inductor voltage drop (p. u.), p, q- instantaneous power components (p. u.). (a) Representation in αβ frame, (b) values related to p and q 1.

where \(\:\omega\:\) shows the grid voltage frequency, \(\:{u}_{g\alpha\:}^{q}\) and \(\:{u}_{g\beta\:}^{q}\) are grid voltage vector components that can be obtained by the second order generalized integrator (SOGI). In addition, the harmonic filter of the direct component signals of the grid voltage (\(\:{u}_{g\alpha\:}^{d}\) and \(\:{u}_{g\beta\:}^{d}\)) is obtained, which can be beneficial for the control system as the voltage harmonics produce unwanted fluctuations in the power component signals, resulting in the distortion of the converter current. Using filtered signals, we have42:

Calculation of reference instantaneous power components oscillations

In order to maintain a sinusoidal current waveform for the converter, the appropriate oscillations of the power components p and q must be referenced. Two general goals may be achieved by current asymmetry including current asymmetry opposite to voltage asymmetry (goal 1) and current asymmetry proportional to voltage asymmetry (goal 2), while the intermediate states are combinations of these two goals. The first goal is beneficial for the grid in inverter mode and the second one is useful in rectifier mode, while the intermediate modes provide the possibility of increasing the available power of the converter. The components of the grid voltage vector can be described as follows by considering only the main harmonic:

where \(\:{U}_{\alpha\:m}\) and \(\:{U}_{\beta\:m}\) are the amplitude of the grid voltage vector components, \(\:{\alpha\:}_{u}\) and \(\:{\beta\:}_{u}\) shows the phase shift between the corresponding vector component and its positive sequence component, \(\:\omega\:\) is the main harmonic frequency. Hence, the main harmonic of the current vector can be described as:

where \(\:\phi\:\) is the phase shift between the positive sequence component of the voltage and current vectors. Depending on the goal, \(\:{\alpha\:}_{i}\) and \(\:{\beta\:}_{i}\) are directly or crosswise corresponded to the voltage phase shift. Similarly, \(\:{I}_{\alpha\:m}\) and \(\:{I}_{\beta\:m}\) are directly or crosswise corresponded to the voltage amplitudes. Then, based on (4) and (5), the fluctuations of power components can be described by (25) and (26) for the first objective and (27) and (28) for the 2nd objective.

where \(\:{\text{I}}_{m\_avg}=\frac{{I}_{\alpha\:m}+{I}_{\beta\:m}}{2}\). Then, the fluctuating parts of the power components, \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{p}\) and \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{q}\), can be calculated using the direct and vertical grid voltage components and the dc parts of the power component, \(\stackrel{-}{p}\) and \(\stackrel{-}{q}\), as follows for objective 1:

And for the objective 2, we have:

However, both power components oscillate for moderate current asymmetry according to Fig. 3. As a result, an additional coefficient, \(\:\xi\:\), is proposed, which decides the contribution of the oscillatory part in each power component. Then, the oscillating parts can be expressed as:

As (33) and (34) describe the reference values, they are calculated by the references \(\stackrel{-}{p}\) and \(\stackrel{-}{q}\). Determining the value of the coefficient \(\:\xi\:\:\)depends on the power limitation as well as the operation mode of the converter.

Power components constraints due to maximum phase current magnitude

The limitation of the power components must ensure that the current in each phase does not exceed the maximum allowed RMS value. Otherwise, a converter may malfunction due to overheating of the semiconductor devices, and if both are designed within a small margin of oversize, inductor saturation may occur. The maximum power is obtained for symmetrical current by considering the sinusoidal waveform of the converter current. Besides, this situation is not beneficail for the grid while the sag voltage is asymmetric, and therefore, the average current asymmetry (between the first and second objectives) should be maintained only if the required power is greater than the allowable range for the certain objective. Considering the dc parts of (25) and (27), the dc parts of the maximum power components can be calculated similar to the reference oscillating parts. Equations (35) and (36) describe the \(\:p\) maximum component assuming \(\:cos\left(\phi\:\right)\:=\:1\) for asymmetric currents of both objectives (|̅|, |̅|).

where \(\:{I}_{max}\) is the maximum rated amplitude of the three-phase current, \(\:{\text{U}}_{II}=\:\left[{\text{U}}_{AII}{\text{U}}_{BII}{\text{U}}_{CII}\right]\) represents three-phase grid voltage amplitudes, \(\:{U}_{I}\)= [\(\:{U}_{AI}{U}_{BI}{U}_{CI}\)] shows the theoretical voltage amplitudes of the opposite three-phase asymmetric to the grid voltage. Assuming that the current is almost symmetrical for \(\:\xi\:=0.5\), the maximum available dc part of the p component can be expressed as:

where \(\:{U}_{p}\) is the amplitude of the positive sequence component of the grid voltage.

where in (45), we have:

The limitation of the q component of the dc part instantaneous power depends on the reference \({\stackrel{-}{P}}^{\text{*}}\) to maintain the priority of the active power.

Determining of factor ξ

Introducing the coefficient ξ allows smooth variation in current asymmetry. This is especially important while exceeding the limitations resulted from the asymmetric current limits. Considering the objective selection associated with the operation mode of the converter, it can be assumed that \(\:\xi\:\le\:0.5\) for \(\:{\stackrel{-}{p}}^{\text{*}}<0\) (in the inverter mode) and \(\:\xi\:\ge\:0.5\) for \(\:{\stackrel{-}{p}}^{\text{*}}>0\) (in rectifier mode). Since \(\:{\upxi\:}=0.5\) represents the maximum power point, it can occur for both rectifier and inverter modes. The value of \(\:\xi\:\) also depends on the reference average apparent power, which is expressed as:

Then. the coefficient \(\:\xi\:\) can be expressed as a linear function of \(\:{s}^{\text{*}}\) as:

Additional restrictions should also be considered such as:

Figure 4 demonstrates the desired graphic function.

Overall control system

The final control system with reference power fluctuations and limiting conditions is illustrated in Fig. 5. A PI controller is considered to control the DC link voltage. However, it should be noted that for objective 2 (the oscillating pcomponent), the DC link voltage also fluctuates with the double grid ω. In addition, high order harmonics of the mains voltage cause additional distortion. Consequently, 2ω fluctuations can be removed by a band-stop filter (notch filter), and if there is a large amount of harmonics in the grid voltage, they can be removed possibly by a low-pass filter31.

Since the reference of the q component is set arbitrarily, it is directly limited. The limitations are calculated based on the maximum hypothetical current magnitude \(\:{I}_{max}\), as well as the filtered direct and vertical grid voltage vector components, provided by SOGI. Then, the reference instantaneous power component limited signals are implemented to calculate the appropriate reference oscillations by using the voltage vectors generated from the SOGI outputs. The SOGI is capable of generating vertical signals for many applications such as frequency estimation, grid synchronization, and harmonic extraction. However, the SOGI is sensitive to input dc components and unknown frequency harmonics (e.g. interharmonics)42.

The instantaneous power components, p and q, are calculated by the filtered grid voltage. This process is conducted to reduce unwanted power fluctuations caused by the occurrence of grid voltage harmonics. Therefore, the instantaneous power components, p and q, contain only dc values and 2ω oscillations due to the asymmetry of voltage and current, and the harmonic impacts are negligible. The error signals, p and q, are sent to the common PI controllers; the outputs are augmented with feedforward \(\:{r}_{pq}\) multiplied by 2/3L. This sum is represented by \(\:{S}_{pq}\) in Fig. 5. Also, the \(\:{S}_{\alpha\:\beta\:}\) signals are calculated by the filtered grid voltage since it is expected that they represent the voltage drop in a grid filter and should have only the fundamental harmonic. This expectation is due to the utilization of the feed-forward main grid voltage. In practice, this feed-forward process has a slight delay due to sampling, even though all inaccuracies must be compensated by the controllers. Finally, the converter voltage calculated in this way is sent to the cascade phase shift modulation block (CPS-PWM) to switch the MMC converter.

The control system operates in a stationary reference frame, bypassing the need for transformations to a synchronous reference frame. This eliminates dependency on phase-locked loops (PLLs) for phase angle determination, simplifying the system and reducing sensitivity to grid voltage asymmetries.

The core strategy revolves around using instantaneous active (p) and reactive (q) power components as control variables. These power components are derived from the grid voltage and converter current in the stationary frame. The control algorithm ensures:

-

Sinusoidal currents, even under unbalanced grid voltage conditions.

-

Active and reactive power regulation with minimal coupling effects.

-

Phase current limitation to prevent overloading.

Simulation results

In this section, the simulation is performed in the Simulink/MATLAB software54 for a three-phase five-level MMC-based power converter according to Fig. 1 along with the control system of Fig. 5. This converter is connected from the DC side to a controlled current source without a capacitor, and it is connected from the AC side to the three-phase power system with a 230 V line-to-line voltage. Since each sub-module has a capacitor, therefore, the sum of series SMs’ capacitors acts as a DC link capacitor and each SM should be able to independently maintain its capacitor voltage constant. The current source on the DC side can exchange active energy between the DC and AC sides of the converter, and it is possible to receive energy from the three-phase system in rectifier mode and return the same energy to the system in inverter mode. In this simulation, the grid voltage contains 0.6% fifth harmonic and 0.5% seventh harmonic. Moreover, the amplitude of phases b and c are unbalanced and have 20% sag voltage. The simulation circuit parameters are presented in Table 2. The simulation results are compared with the results presented in5 to confirm the effect of implementing the proposed MMC converter in comparison with the two-level converter with SVM modulation.

Figure 6 depicts the effect of the feed-forward \(\:{r}_{pq}\) loop during the step change of the average p components. The lack of this feed-forward loop leads to obvious coupling between the instantaneous power components. Considering \(\:{r}_{pq}\:\)provides the possibility of reducing this phenomenon,, and thus, improving the control dynamics. However, the presence of \(\:{r}_{pq}\:\)in the simulations do not show a significant impact.

According to Fig. 6a, it can be seen that when the reference active power changes from zero to 2000 W, the sign of the output active power is positive which means the MMC converter is operating in the mode of absorbing power from the ac system and sending it to the dc system, i.e. the rectifier mode. Conversely, it can be seen from Fig. 6b that when the reference active power changes from zero to 2000 W, the MMC output active power sign is negative, and therefore, the converter receives the dc energy and delivers it to the ac grid, i.e. the inverter mode.

Active power variation in inverter mode

Figure 7 shows the comparative results of the outputs of the proposed MMC converters and the common two-level SVM in inverter mode and active power step change. Figure 7a presents the three-phase grid voltages. It can be observed that the total harmonic distortion (THD) of the grid voltages with the proposed MMC converter is significantly lower than that of the two-level SVM converter which is clearly illustrated in Fig. 8b. According to this figure, the THD of all phases of the voltage obtained by the MMC converter is below 3%, while it is above 12% by the common two-level converter. However, this can not be said for the THD of the current phases. It means that the THD of the phase currents obtained by the MMC converter is not necessarily below that of the two-level converter. Figure 8 depicts the comparison of THD of current phases provided by either MMC or common SVM converters.

According to Fig. 8, the THD of the current phases obtained by the common SVM converter is below 3%, while that of the proposed MMC converter is above 3%. It is worth mentioning that based on Fig. 7b, the polarity of the three-phase asymmetric currents is opposite to the polarity of the three-phase asymmetric voltages in the inverter mode (P < 0). the dynamic change of the DC link voltage with a step change in active power is shown in Fig. 7c for the inverter mode. Before changing the reference active power, the DC link voltage is at its reference value of 390 V. As long as a step change occurs in the active power, an undershoot is observed in the DC voltage magnitude up to 340 V, and immediately returns to its reference value within 100 ms. This is almost the same for both proposed and common converters.

The average and instantaneous active and reactive powers in the active power step change are presented comparatively in Figure 9 for inverter mode. It is observed that by using the proposed multi-level MMC converter, the instantaneous active and reactive power ripple amplitudes are significantly low and equal to 400 W and 500 Var, respectively. However, the amplitudes of ripple and distortion for instantaneous active and reactive power in the two-level converter with common SVM modulation are 1000 W and 1500 Var, respectively. This shows the ability and effectiveness of using the MMC converter in reducing the distortion and ripple of its output power.

The capacitors’ voltage associated with each sub-module (SM) of the upper and lower arms of the phase c in the MMC converter is demonstrated in Fig. 10 for the inverter mode and step change of active power. Firstly, the voltage of all the capacitors placed in the upper and lower SMs is equal, and there is a 180 degree phase difference between the DC voltage of the upper and lower arms (Fig. 10c). Secondly, the voltage ripple amplitude of the SMs’ capacitor in the upper arm (Fig. 10a) is equal to the ripple amplitude in the lower arm (Fig. 10b) and is 15 V. Thirdly, the average capacitor voltage amplitude of each SM is 78 V according to the reference DC voltage amplitude which is 390 V, and there are five SMs in each arm, i.e. 390/5 = 78 V.

The unfiltered output line-to-line voltage of the five-level MMC converter is given in Fig. 10d. Obviously, by increasing the number of SMs in each arm, and subsequently, increasing the number of output voltage levels of the converter, the sinusoidal waveform can be approached, and the output voltage THD is significantly reduced only using smaller filters at the output of the converter, which is among the main advantages of implementing MMC.

Active power variation in rectifier mode

Figure 11 presents the simulation results for the proposed MMC converter and two-level SVM in rectifier mode and step change of reference active power from zero to +2 kW. Here, the asymmetric current matches the asymmetric voltage which can be observed in figure 11b. Besides, the grid voltage has a lower THD in the presence of MMC compared to the common SVM according to Figure 12(b). So the THD of the grid voltage phases obtained by the MMC converter is below 2%, while this reaches 14% for the common two-level converter. It can be concluded based on Figure 12(a) that with both the proposed and common converters, the amount of THD of all three current phases does not exceed 2.5%, which is desirable and acceptable. However, the current THD obtained by the MMC converter in this case is less than or equal Fig. 11: Simulation results in the rectifier mode during step change of reference active power from 0 to 2 kW for conventional SVM (left column) and proposed MMC (right column). (a) PCC voltage, (b) grid currents, (c) DC-link voltage, (d) active and reactive powers of converter to that of the SVM two-level converter

Moreover, the DC voltage dynamics in the rectifier mode are demonstrated in Fig. 12c. With the step change in active power at t = 0.2s, the DC voltage experiences an overshoot with an amplitude of about 60 V by implementing the MMC converter and is recovered in less than 80 ms. The overshoot amplitude of DC voltage obtained by the SVM converter is almost 70 V. Clearly, the step change of the energy transfer in the DC link results in temporary current balancing, which with the aid of the maximum active power, maintains the sinusoidal current waveform and quickly achieves the reference DC bus voltage.

Figure 13 depicts the comparison of instantaneous and average powers for MMC and SVM converters in rectifier mode. The capability of the proposed MMC converter in reducing distortion and double frequency ripple of instantaneous active and reactive powers is clearly visible. The amplitude of active and reactive power ripple obtained by the proposed method is 500 W and 200 Var, respectively, while that of the common two-level converter is 1000 W and 1000 Var, respectively.

For example, the behavior and performance of the voltage of capacitors in the upper and lower arm of the SM obtained by the MMC converter are shown in Fig. 14 in the rectifier mode. As observed, the average DC voltage magnitude and its ripple for all SMs in both upper and lower arms are equal and balanced. The ripple amplitude of double grid frequency (Hz100) observed in the DC voltage of all capacitors is 10 V.

Frequent changes in active power

In the next step, the simulation is performed with frequent changes in active power while reactive power is zero. According to Fig. 15, the active and reactive powers are zero until t = 0.3s. At t = 0.3s, the reference active power is increased stepwise from zero to −1.8 kW and the converter is operated in inverter mode. The active power becomes zero again at t = 0.6s and the amplitude of the corresponding currents is zero (Fig. 15b). During this period, the double grid frequency ripple is evident in the reactive power waveform (Fig. 15d). Additionally, the polarity of the asymmetric currents is opposite to the polarity of the asymmetric grid voltage in this case.

At t = 0.8s, the reference active power changes stepwise from zero to + 1.8 kW and the amplitude of currents reaches about 7 A. Here, the converter is operated in the rectifier mode, and the asymmetric current matches and is in the same direction as the asymmetric voltage. In this case, the double grid frequency ripple (Hz100) affects the active power curve and the reactive power curve is without ripple (Fig. 15d). At t = 1.1s, the active power reaches zero again. The slow dynamics of the DC link voltage can be observed in Fig. 15c. During each change in the active power, an undershoot (in the inverter mode) and an overshoot (in the rectifier mode) appear in the DC voltage depending on the operational mode of the MMC converter. The maximum settling time in all cases is less than 100 ms.

The performance of MMC submodules in the active power step change mode is demonstrated in Fig. 16. Despite the frequent changes in active power, the voltage of capacitors in all SMs is the same. Also, there are fluctuations in the voltage of the capacitors proportional to the voltage fluctuations of the DC link after each change in power, which are immediately damped after a few cycles and are placed around their operational point, i.e. 78 V. Therefore, after any disturbance in power, the voltage of each capacitor in each SM is balanced. In addition, the voltage ripple amplitude of the capacitors does not exceed 10 V. The unfiltered line-to-line output voltage waveform of the converter also remains stable during power disturbances (Fig. 16d). This is due to the stability and maintaining the balance of SMs’ voltages.

The comparison of instantaneous and average powers is illustrated in Fig. 17 for the case of frequent step changes in the active power of both the two-level SVM converter and multi-level MMC converter. Clearly, the distortion and amplitude of instantaneous active and reactive power fluctuations are significantly decreased by the proposed MMC converter compared to the common SVM converter. The active power ripple amplitude is mitigated by 2 times compared to the common design. The reactive power ripple amplitude is reduced by 3 times in inverter mode and 5 times in rectifier mode.

Frequent changes in reactive power

The proposed control system provides reactive power supporting. The step change in q component is depicted in Fig. 18 for both rectifier and inverter operating modes. The active power flow is also performed here as a special case study. In this simulation, the reference reactive power changes repeatedly between + 1.5 kVar and − 1.5 kVar during 0 < t < 0.7s. At t = 0.35s, the active power reference changes from − 600 W to + 600 W. According to Fig. 18, as long as the converter works in inverter mode (p < 0), the reactive power curve, regardless of its sign, contains a double grid frequency ripple (100 Hz) and the DC link voltage is almost without ripple. Is. In this case, the polarity of the asymmetric current is opposite to the polarity of the asymmetric voltage. At t = 0.35s, the converter is operated in the rectifier mode (p > 0) and the polarity of the asymmetric current is in the same direction as the polarity of the asymmetric voltage. Thus, the active power curve, and consequently, the DC link voltage contain ripple, and the reactive power is without ripple.

The waveforms of the capacitor voltage in SMs of phase c and their performance against step changes in reactive power are shown in Fig. 19. It seems that by changing the sign of the reactive power, the direction of the maximum ripple amplitude also varies. Nevertheless, the SMs’ voltage ripple amplitude is still 10 V and the average voltage value of the capacitors remains constant at its reference value (78 V).

It can be clearly seen from Fig. 20 that the amplitude of the ripple and fluctuations of instantaneous power are significantly decreased by using the proposed multilevel MMC converter. This proves the capability and effectiveness of using the proposed MMC converter.

Linear variation of active power

Figure 21 provides the linear change in the active power from low to high saturation level. During 0.2s < t < 0.6s, the active power reference of the converter varies from − 2 kW to + 2 kW with a positive slope of 10 kW/s. As observed, both current balance and limitation are directly associated with power limitation. The asymmetric current changes due to the reference power as well as the sign of the active power. The amplitude of three-phase currents is limited to less than the allowed value of 10 A under any condition. In order to achieve the intermediate asymmetric current, and finally, the symmetric current, the fluctuation of both power components is produced. The maximum power is then obtained for both rectifier and inverter modes.

Figure 22 shows the change of ξ for the same conditions considered in Fig. 21. The coefficient ξ is considered as zero for the inverting mode and one for the rectifier mode. The value of ξ varies according to the change in the reference power according to (49).

Figures 23 and 24 illustrate the output voltage and current hodographs of the converter, respectively. In the voltage hodograph presented in Fig. 23, the β component related voltage changes are drawn in terms of the α component, which is almost elliptical.

The current hodograph presented in Fig. 24 is depicted in two modes. On the left side of the figure, the current change slope is positive, while this slope is negative on the right side. Additionally, the β component current changes are plotted in terms of α component in this case.

Conclusion

This paper introduced an innovative control strategy for grid-connected three-phase Modular Multilevel Converters (MMC), designed to operate under harmonic and asymmetric grid voltage conditions. The proposed method leverages instantaneous power component control in a stationary reference frame, eliminating the need for symmetrical sequence decomposition or trigonometric transformations. By employing oscillating reference signals and current balancing strategies, the approach ensures that phase currents remain within permissible limits while maintaining sinusoidal waveforms.

Key findings from the simulation studies include:

-

Superior Harmonic Performance: The proposed MMC achieved voltage THD below 3% in inverter mode and under 2% in rectifier mode, significantly outperforming a conventional two-level SVM converter.

-

Enhanced Power Ripple Reduction: Ripple amplitudes in instantaneous active and reactive powers were reduced by 2.5 times in inverter mode and up to 5 times in rectifier mode compared to the SVM-based approach.

-

Dynamic Current Asymmetry Management: The method effectively handled asymmetric currents, aligning them with or opposing asymmetric voltages, depending on the operational mode.

-

Robust Current THD: In both inverter and rectifier modes, the phase current THD remained below 2.5%, comparable to or better than conventional designs.

The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the MMC-based control strategy in mitigating harmonics, reducing power ripple, and enhancing overall system performance under challenging grid conditions. Future work will focus on experimental validation and hardware implementation to ensure scalability and adaptability in practical grid applications.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

02 December 2025

This article has been retracted. Please see the Retraction Notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30609-x

References

Agajie, T. F. et al. Enhancing Ethiopian power distribution with novel hybrid renewable energy systems for sustainable reliability and cost efficiency. Sci. Rep. 14, 10711 (2024).

Nadermohammadi, A. et al. Cost-effective soft-switching ultra-high step-up DC–DC converter with high power density for DC microgrid application. Sci. Rep. 14, 20407 (2024).

Aghdam, E. A. et al. A new IGDT-based robust model for day-ahead scheduling of smart power system integrated with compressed air energy storage and dynamic rating of transformers and lines. J. Energy Storage. 105, 114695 (2025).

Rashid, S. M. Employing advanced control, energy storage, and renewable technologies to enhance power system stability. Energy Rep. 11, 3202–3223 (2024).

Wodyk, S. & Iwanski, G. Control of three-phase power electronic converter with power controllers in stationary frame. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 56, 5257–5268 (2020).

Zargari, N. R. & Joos, G. Performance investigation of a current-controlled voltage-regulated PWM rectifier in rotating and stationary frames. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 42, 396–401 (1995).

Rim, C. T., Choi, N. S., Cho, G. C. & Cho, G. H. A complete DC and AC analysis of three-phase controlled-current PWM rectifier using circuit DQ transformation. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 9, 390–396 (1994).

Ohnishi, T. Three phase PWM converter/inverter by means of instantaneous active and reactive power control. in Proceedings IECON’91: International Conference on Industrial Electronics, Control and Instrumentation 819–824 (IEEE, 1991). (1991).

Mahmoudi Rashid, S., Rikhtehgar Ghiasi, A. & Ghaemi, S. A new distributed robust H ∞ control strategy for a class of uncertain interconnected large-scale time-delay systems subject to actuator saturation and disturbance. J. Vib. Control https://doi.org/10.1177/10775463241259345 (2024).

Wu, F., Liu, R., Xie, Y. & Lyu, J. A modified power decoupling control strategy for a grid-connected inverter with a low switching frequency under unbalanced grid voltages. Energy Rep. 8, 757–768 (2022).

Ebrahim, M. A., Aziz, B. A., Nashed, M. N. & Osman, F. Optimal design of controllers and harmonic compensators for three-level cascaded control in stationary reference frame for grid-supporting inverters-based AC microgrid. Energy Rep. 8, 860–877 (2022).

Dang, C., Tong, X. & Song, W. Sliding-mode control in dq-frame for a three-phase grid-connected inverter with LCL-filter. J. Frankl. Inst. 357, 10159–10174 (2020).

Malinowski, M., Jasinski, M. & Kazmierkowski, M. P. Simple direct power control of three-phase PWM rectifier using space-vector modulation (DPC-SVM). IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 51, 447–454 (2004).

Bebboukha, A. et al. Finite control set model predictive current control for three phase grid connected inverter with common mode voltage suppression. Sci. Rep. 14, 19832 (2024).

Akbari, E. & Seyyedi, A. Z. G. Multi-functional voltage and current based enhancement of power quality in grid-connected microgrids considering harmonics. Heliyon 10, e26008 (2024).

Sato, Y., Ishizuka, T., Nezu, K. & Kataoka, T. A new control strategy for voltage-type PWM rectifiers to realize zero steady-state control error in input current. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 34, 480–486 (1998).

Jia, L., Tian, Y., Liu, Z. & Zhang, X. Controlled synchronization of three co-rotating exciters based on a circular distribution in a vibratory system. Sci. Rep. 14, 5026 (2024).

Zmood, D. N. & Holmes, D. G. Stationary frame current regulation of PWM inverters with zero steady-state error. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 18, 814–822 (2003).

Hwang, J. W. G., Winkelnkemper, M. & Lehn, P. W. Design of an optimal stationary frame controller for grid connected ac-dc converters. in IECON -32nd Annual Conference on IEEE Industrial Electronics 167–172 (IEEE, 2006). (2006).

Guo, X. & Ghadimi, N. Optimal design of the proton-exchange membrane fuel cell connected to the network utilizing an improved version of the metaheuristic algorithm. Sustainability 15, 13877 (2023).

Akbari, E. & Seyyedi, A. Z. G. Power quality enhancement of distribution grid using a photovoltaic based hybrid active power filter with three level converter. Energy Rep. 9, 5432–5448 (2023).

Holmes, D. G., Lipo, T. A., Mcgrath, B. P. & Kong, W. Y. Optimized design of stationary frame three phase AC current regulators. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 24, 2417–2426 (2009).

Hwang, J. G., Lehn, P. W. & Winkelnkemper, M. A generalized class of stationary frame-current controllers for grid-connected AC–DC converters. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 25, 2742–2751 (2010).

Zou, C., Liu, B., Duan, S. & Li, R. Stationary frame equivalent model of proportional-integral controller in dq synchronous frame. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 29, 4461–4465 (2014).

Roiu, D., Bojoi, R. I., Limongi, L. R. & Tenconi, A. New stationary frame control scheme for three-phase PWM rectifiers under unbalanced voltage dips conditions. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 46, 268–277 (2009).

Ye, H., Jin, G., Fei, W. & Ghadimi, N. High step-up interleaved dc/dc converter with high efficiency. Energy Sources Part. Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 46, 4886–4905 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Control of three-phase boost-type PWM rectifier in stationary frame under unbalanced input voltage. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 25, 2521–2530 (2010).

Rashid, S. M. Does the application of Jensen’s integral inequality and LMIs confirm exponential stability in delayed systems with gapped gamma distribution through augmented Lyapunov function? Heliyon 10, (2024).

Wang, F., Duarte, J. L. & Hendrix, M. A. Pliant active and reactive power control for grid-interactive converters under unbalanced voltage dips. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 26, 1511–1521 (2010).

Camacho, A., Castilla, M., Miret, J., Borrell, A. & de Vicuña, L. G. Active and reactive power strategies with peak current limitation for distributed generation inverters during unbalanced grid faults. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 62, 1515–1525 (2014).

Iwanski, G., Luszczyk, T. & Szypulski, M. Virtual-torque-based control of three-phase rectifier under grid imbalance and harmonics. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 32, 6836–6852 (2016).

Iwanski, G. Virtual torque and power control of a three-phase converter connected to an unbalanced grid with consideration of converter current constraint and operation mode. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 34, 3804–3818 (2018).

Rioual, P., Pouliquen, H. & Louis, J. P. Regulation of a PWM rectifier in the unbalanced network state using a generalized model. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 11, 495–502 (1996).

Yepes, A. G., Vidal, A., López, O. & Doval-Gandoy, J. Evaluation of techniques for cross-coupling decoupling between orthogonal axes in double synchronous reference frame current control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 61, 3527–3531 (2013).

Malinowski, M., Marques, G., Cichowlas, M. & Kazmierkowski, M. New direct power control of three-phase PWM boost rectifiers under distorted and imbalanced line voltage conditions. in IEEE International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (Cat. No. 03TH8692) vol. 1 438–443 (IEEE, 2003). (2003).

Converters, G. C. V. S. Improved Direct Power Control for Grid-Connected Voltage Source Converters. (2018).

Nian, H., Shen, Y., Yang, H. & Quan, Y. Flexible grid connection technique of voltage-source inverter under unbalanced grid conditions based on direct power control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 51, 4041–4050 (2015).

Zhang, Y. & Qu, C. Direct power control of a pulse width modulation rectifier using space vector modulation under unbalanced grid voltages. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 30, 5892–5901 (2014).

Zhang, Y., Liu, J., Yang, H. & Gao, J. Direct power control of pulsewidth modulated rectifiers without DC voltage oscillations under unbalanced grid conditions. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 65, 7900–7910 (2018).

Chevinly, J. et al. Gallium Nitride (GaN) based High-Power Multilevel H-Bridge Inverter for Wireless Power Transfer of Electric Vehicles. ArXiv Prepr. ArXiv240511131 (2024).

Hagiwara, M. & Akagi, H. PWM control and experiment of modular multilevel converters. in IEEE Power Electronics Specialists Conference 154–161 (IEEE, 2008). (2008).

Knaak, H. J. Modular multilevel converters and HVDC/FACTS: A success story. in Proceedings of the 14th European conference on power electronics and applications 1–6 (IEEE, 2011). (2011).

Ramirez, D., Zarei, M. E., Gupta, M. & Serrano, J. Fast model-based predictive control (FMPC) for grid connected modular multilevel converters (MMC). Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 119, 105951 (2020).

Elsanabary, A., Hashfi, T. B., Mekhilef, S., Seyedmahmoudian, M. & Stojcevski, A. Submodule fault-tolerant control based adaptive carrier-PDPWM for modular multilevel converters. Energy Rep. 7, 7288–7296 (2021).

Zhang, H., Ma, Y., Yuan, K., Khayatnezhad, M. & Ghadimi, N. Efficient design of energy microgrid management system: a promoted Remora optimization algorithm-based approach. Heliyon 10, e23394 (2024).

Luo, Y., Jia, Z., Xu, L., Li, Q. & Song, Y. A reduced switching frequency capacitor voltage balancing control for modular multilevel converters. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 142, 108272 (2022).

Yu, J. & Xia, C. Operation and control schemes of a novel direct AC-AC modular multilevel converter. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 139, 108037 (2022).

Niaki, A. A. & Jamil, M. An efficient hydrogen-based water-power strategy to alleviate the number of transmission switching within smart grid. Int. J. Hydrog Energy. 70, 347–356 (2024).

Jamaludin, J., Syamsuddin, S., Rahim, N. A. & Ping, H. W. Control of switch-sharing-based multilevel inverter suitable for photovoltaic applications. J. Frankl. Inst. 355, 1018–1039 (2018).

Chandrasekaran, S., Durairaj, S. & Padmavathi, S. A performance evaluation of a fuzzy logic controller-based photovoltaic-fed multi-level inverter for a three-phase induction motor. J. Frankl. Inst. 358, 7394–7412 (2021).

Trivedi, T. et al. Sliding mode-based direct power control of unified power quality conditioner. Heliyon 10, (2024).

Rath, A. & Srungavarapu, G. An advanced shunt active power Filter (SAPF) for non-ideal Grid using predictive DPC. IETE Tech. Rev. 40, 521–534 (2023).

Rath, A. & Srungavarapu, G. Reduced complexity model predictive direct power control for unbalanced grid. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 234, 110563 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ehsan Akbari: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article has been retracted. Please see the retraction notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30609-x

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akbari, E. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Stationary-frame power regulation for controlling grid-connected three-phase modular multilevel converter with low harmonic under unbalanced voltage. Sci Rep 15, 5878 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90236-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90236-4