Abstract

Meteorites are a unique source of geological information about our early Solar System and the difference between planets and asteroids. In this study, meteorite Ribbeck (2024 BX1, SAR 2736) from the recently fallen asteroid (21.01.2024), collected right after the fall, was investigated. This meteorite is classified as a coarse-grained brecciated aubrite. The main mineral phases are enstatite, albite, and forsterite. X-ray structural analysis and Raman Spectroscopy indicate its complex metamorphic history, starting with magmatic crystallization and following metamorphic evolution (e.g., impacting). Energy-dispersive. X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) confirms the presence of unusual minerals such as oldhamite, brezinanite (daubréelite, zolenskyite), wassonite/heideite, and alabandite, that formed under highly reductive conditions, with oxygen fugacity ΔIW (logfO2) in a range of -5 to -7. Similar conditions can be found on the Mercury or the Asteroid 3103 Eger. Magnetic measurements confirm that the primary magnetic components in the meteorite are accessory minerals - sulphides and metallic nodules.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Today, humankind can send spacecraft, landers, and rovers to another planet, with each one leaving, except the obtained knowledge, numerous questions to be answered. When it comes to planetary science, it is commonly known that meteorites are a great source of knowledge, especially about the formation and evolution of the Solar System1,2, but most of the found meteoritic pieces already interacted with the Earth’s atmosphere (and water) which in many cases resulted in their incomparably high level of weathering3.

Therefore, meteorites collected right after the fall are even more valuable from a scientific point of view. Each day, several tons of meteorites reach the surface of our planet, most of which are just cosmic dust4. Most known meteorites originate from the Asteroid Belt between Mars and Jupiter5. The first observation of an asteroid was made over 200 years ago, to be exact, in 1801 by Giuseppe Piazzi6. However, the first asteroid observed that was confirmed to impact the Earth’s atmosphere was made by Richard A. Kowalski just in 2008, only a day before the fall7. The meteorite fall took place on October 7th at 02:46 GM. It entered the atmosphere and fell above northern Sudan8. The meteorite, later named “Almahata Sitta,” is already one of the best-known anomalous urelite-type meteorites and, as mentioned above – the first one originating from an asteroid that was first to be confirmed to collide with our planet before the phenomenon9. Recently, an analogous occurrence took place. The asteroid SAR2736 (2024 BX1), observed just several hours before impact by Krisztián Sárneczky, entered the atmosphere on January 21st, 2024, at 00:32 UTC (01:32 CET). The harmless meteorite shower took place near Berlin, Germany – in the town of Ribbeck. It was already the eighth and smallest asteroid observed before impacting Earth’s atmosphere.

In this paper, we investigate, in a non-destructive manner, the mineral composition and structural analysis of the Ribbeck meteorite obtained from two different pieces found by an author. First, the paper focuses on the chemical analysis of the different phases of the meteorite using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) followed by structural analysis using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Raman spectroscopy, and finally on magnetic response of selected pieces using superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID). Our studies show that the meteorite mainly comprises the enstatite, albitic plagioclase, and small assistance of the forsterite crystals and sulphides, consistent with aubrite-type meteorites. X-ray diffraction followed by Raman spectroscopy confirms that enstatite is characterized by the Pbca space group, with smaller elementary cell parameters than enstatite observed naturally existing on Earth. Albitic plagioclases (despite most being pure albite) can be classified as an albite-oligoclase-type of feldspars. Analysis under an electron microscope confirms no presence of Fe in enstatite. It reveals several sulphides, such as troilite (FeS), oldhamite (CaS), alabandite ((Mn, Fe)S), and brezinaite enriched with Ti (Cr3S4). Several metallic nodules built of FeNi (enriched with Ca and Si) were also observed. Additionally, several nodules built of Fe-Cr (with signs of Si and S) were noticed, but they most likely formed as sulfides melting products upon entry into the atmosphere.

Strewn field

Due to early predictions, plenty of videos and data were available for the science; thus, three teams attempted to calculate the possible strewn field for a meteorite fall - Pavel Spurný, Jiří Borovička, and Lukáš Shrbený from the Czech Republic10, Denis Vida’s team from The University of Western Ontario in Canada and Jim Goodall from the USA. All three maps overlapped, confirming the accuracy of each calculation, which led the meteorite hunters and scientists to the field, where they discovered over 1.7 kg of meteoritic matter in over 200 pieces11. Ribbeck strewnfield represents an inversed type, which means the size of recovered meteorites was arranged from the biggest on the west, to the smallest on the east. If the fall was not observed, one could conclude that the strewnfield clearly shows that the meteorite fall took place from east to west. Nevertheless, the asteroid entered the atmosphere of Earth at a steep angle (only about 14.5° from the vertical, ENE) with a velocity of 15 km s−1. The gale coming from the WNW created a strewn field that was rotated approximately 139° between the fall’s directions and the strewn field’s elongation. The predicted strewn field calculations, asteroid trajectory, and meteorological information were recently published10.

Ribbeck (2024 BX1) – an Aubrite

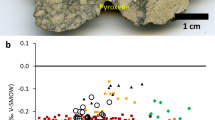

According to The Meteoritical Society (Meteoritical Bulletin Database), the 2024 BX1 meteorite (Fig. 1) was classified as an aubrite by Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin and received the name “Ribbeck”. Aubrites are extremely rare enstatite achondrite-group meteorites, which are mainly composed of enstatite (Mg-rich pyroxene), albitic plagioclase, almost Fe-free diopside, forsterite, and unusual sulphides, naming several – troilite (FeS), oldhamite (CaS), brezinaite (Cr3S4) or heideite (FeTi2S4)12. They also contain small amounts of Si-bearing FeNi metal13, resulting from highly oxygen-depleted conditions, most likely unknown to Earth nowadays14. Most known aubrites and enstatite chondrites contain similar isotopic variations for Cr, Ca, and Ti, remarking that, most likely, these meteorites originate from a common celestial source15. Aubrites, just like enstatite chondrites, went through metamorphic (impactful) events in early Solar System formation16. It was suggested17that over time, the rocks originating from the Aubrite Parent Body (AuPB), after its possible destruction, were captured by other planets and asteroids. Reaccretion like this is one potential explanation for mesosiderite-type meteorite formation18.

Cosmic ray exposure and origin of aubrites

Aubrites are also known for their very long cosmic ray exposure (from about ~ 12 Myr for Aubres, up to over 100 Myr for Norton County), which is among the longest stony-type meteorites, marking their pre-irridation as a part of a parent body19. Mineral phases in aubrites crystallized just about 4.5–4.8 Ma after the Solar system formation20. Aubrites’ chemical composition also matches the enstatite-high and enstatite-low (EH and EL) chondrites, which could lead to the conclusion that they could share the parent body. However, when comparing these two types, several differences have to be marked: the difference in cosmic ray exposure time; a five times higher abundance of Fe-Ni to troilite ratio in the case of aubrites; lack of chondritic clasts in brecciated aubrites; the difference in metallic grain bulk composition; different rare earth elements (REE) content in oldhamite21,22. Trace element analysis of aubrites not only confirms their igneous origin23, but also suggests that after their formation, most aubrites underwent metamorphic stages, including impactful events24. Moreover, the variation of REE among the minerals in aubrites could not have been caused only by fractional crystallization from magma. Rather, it suggests an incomplete equilibrium, indicating brief melting events that resulted in segregating metals and sulphides25. Aubrites represent the most reduced magmatic conditions in the achondrite-type meteorite group, with oxygen fugacity ΔIW (logfO2) ranging from − 5 to −726. The cooling rate of aubrites (for instance, Norton County is estimated to be 1–10 K / Ma)27 is also much slower than the cooling rate of enstatite chondrites (for instance, for Abee, it was about 100 K / hour)28. The AuPB of the most known aubrites are different and are proposed to be E- and E(II)- type asteroids, such as 3103 Eger or 2867 Steins21. Unlike a howardite–eucrite–diogenite (HED) group, whose parent body is closely related to asteroid 4 Vesta29,30, no such object matches perfectly in the solar system for aubrites31. It was noticed that the composition of aubrites could be similar to that of enstatite chondrites’ parent bodies32. However, for enstatite chondrites, one of the more probable options for a parent body is an asteroid (16) Psyche33. Spectral analysis of aubrites confirms that they generally match with those of Tholen E-/Bus-DeMeo Xe-type asteroids; still, the near-infrared analysis reveals that the match is not perfect34. This difference can be explained by the cosmic dust covering an asteroid’s surface - and a similar case of spectra difference was reported recently on Ryugu35. In the case of the Ribbeck, spectra analysis of meteorite pieces was recently performed, and it was confirmed that it was consistent with other aubrites36.

Similarities to the proto-Mercury

The literature suggested that aubrites could be related to the surface of the Mercury37. Similarities have been pointed out multiple times14,22,38. Both aubrites and the surface of Mercury are composed mainly of Fe-poor pyroxene (enstatite), olivine (forsterite), Na-rich plagioclase (albite), and Mg-Ca-Fe sulphides39. It also confirmed that Mercury’s silicates-crust has been differentiated40. Moreover, the oxygen fugacity ΔIW (logfO2) of aubrites (−5 to −7)26 is almost identical to those of the surface of Mercury (−5 to −6.5)41. Petrological modeling of Mercury’s crustal composition results in similar conclusions that its surface is mainly built of norite (an igneous rock composed of plagioclase, orthopyroxene, and olivine)42. However, the model proved that feldspar on the Mercury should be highly enriched with Ca, such as on the Moon43, which is not the case with aubrites (mostly Na-type). Moreover, the spectral analysis of Mercury’s surface reveals that the lower crust and upper mantle should be enriched in Fe and Ti oxides44. This type of analysis left immediate answers of a possible parent body, for instance, an asteroid Vesta – for specific basaltic (HED group) achondrites45, and additionally of Vestas’ origin, history, mineralogical characterization and diversity29,46,47.

(A) and (B) Ribbeck meteorite fragment weight 22.04 gram, size 3 × 2,5 × 2 cm, collected February 3rd 2024, 11:21 CET (UTC + 1) by Mieszko Kołodziej. The whole specimen is covered with a very thin bubbly glass-like transparent fusion crust. (C) and (D) interior part of the Ribbeck meteorite. White crystals are enstatite, darker grey matrix is composed of mainly enstatite (with feldspar and forsterite). Darker spots are sulphides and metallic fraction (FeNi).

Results

X-ray diffraction and mineral composition (EDS)

X-ray diffraction confirmed the main presence of orthorhombic phase with the Pbca space group (Fig. 2A, En), with elementary cell parameters in a range of a = 18.05–18.15 (+/- 0.03), b = 8.67–8.81 (+/- 0.02) and c = 5.09–5.21 (+/- 0.02) Å, which is identified as enstatite. Enstatite crystals contain 38–42% of MgO, 58–61% of SiO2, and a trace amount of CaO (0–0.9%). It is also important that there was no iron (Fe2O3) in the structure of enstatite crystals, except for those in the closest neighborhood to sulphides (Fig. 4D), where an enrichment in Fe and S was observed, which shows an interaction between these phases, most likely long after the crystallization from magma (caused by metamorphism, diffusion). Nevertheless, as mentioned above, the most analyzed enstatite crystals were almost pure MgSiO3. No diopside crystals were observed. The orthorhombic phase with the Pmnb space group is identified as a forsterite (Fig. 2A, Fo). The observed olivine crystals contained 25–57% MgO, 3–27% Fe2O3, and 0–16% MnO. It is important to note that analysis conducted on various olivine crystals revealed differences in composition. Most analyses show that olivines are mostly pure forsterite (Fo100) and forsterite-fayalite type (Fo50–73Fa27–50). One of the olivine crystals has high MnO content (Fo38Fa39Te23) with a small amount of Ca in its structure (0.3–0.5% CaO). The observed triclinic (anorthic) phase with a C-1 space group is identified as an albite (feldspar) (Fig. 2A, Ab). Yet, as shown in Fig. 2A, these two phases are just a minority. Feldspars are mainly composed of Na2O (7–13%), CaO (0–2.6%), Al2O3 (17–21%), and SiO2 (67–71%), with a trace amount of K2O (0.4–1.8%). According to EDS analysis, signs of zonal crystallization in feldspars were absent. As shown in the ternary diagram (Fig. 2B), most of the observed plagioclases in the 2024 BX1 meteorite are of the albite type (Ab93An5Or2, Ab93An4Or3, and Ab92An5Or3,). Only two crystals were classified as oligoclase (Ab77An9Or14 and Ab72An22Or6), and one as anorthoclase (Ab82An0Or18). Troilite crystals (Figs. 3E and 4A) have a chemical composition of Fe (48–55 at%), and S (37–49 at%) included with a trace amount of Ti (0–6 at%), Cr (0–4,8 at%) and Ca (0–10 at%). Brezinaite crystals (Figs. 3A and C and 4, A and B) were composed of Cr (29–47 at%), S (38–66 at%), and Ti (2–5 at%), with a trace amount of Ca (0–5 at%), Fe (0–2.5 at%) Ni (0–0.2 at%) and Mn (0–0.3 at%). However, using only EDS investigations, it was impossible to distinguish them from freshly discovered zolenskyite48. Alabandite (Fe) crystals (Fig. 4A, C, F) were composed of Mn (28–41 at%), Fe (12–19 at%),

(A) X-ray diffraction pattern of two different 2024 BX1 meteorite pieces (En- orthoenstatite, Fo – forsterite, Ab- albitic plagioclase) and (B) Ternary diagram for feldspars observed in the Ribbeck meteorite (Ab- albite (Na-), Or- orthoclase (K-) and An- anorthite (Ca-) feldspars). As shown in the diagram, most of the plagioclases are classified as an albite (Ab).

Backscattered electron (BSE) images of Ribbeck meteorite focused on crystal form of sulphides (light gray, white) such as (A) wassonite/heideite (Cr), (A), (B) brezinaite, (A), (C), (F) alabandite, (E) oldhamite, (F) daubréelite/zolenskyite, (F) bubbles filled with sulphides that most likely recrystallized due to melting while entering the Earth’s atmosphere.

S (42–56 at%) with a trace amount of Ca (0.3–0.5 at%) and Cr (0–0.3 at%). Oldhamite crystals (Fig. 4E) were hard to analyze because of their possible initial weathering, which affected their composition. In this work, we present just two analyses with Ca (49–51 at%) and S (49–50 at%) with a trace amount of Mn (0–0.6 at%). Metallic concentrations are mostly kamacite crystals (FeNi) (Fig. 4D), with over 80 at% of Fe, 0–2 at% of Ni, and enriched with Ca (0.2–14 at%) and Si (0–3 at%). An enrichment of Ti (up to 6 at%) and K (0–0.2 at%) was detected occasionally. Several different metallic concentrations were detected near the fusion crust, with a composition of CrFe, which most likely formed due to the melting of sulphides on the atmosphere entrance (Fig. 3D, F) (according to the metallic compositions previously brezinaite, daubréelite or unknown yet sulphides). The observed crystal of kamacite (Fig. 4A) had a schreibersite rim around it, which also accumulated Ni (39 at%). Detailed results of the EDS investigations are presented in Table 1.

Raman Spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy was used to aid in identifying mineral phases in the meteorite. Several representative spectra for three mineral phases, which are enstatite, plagioclase(albite), and forsterite, are shown in Fig. 5. The main component, enstatite, with an orthorhombic Pbcasymmetry group, has characteristic Raman lines at 342, 663, 684, 1012, and 1032 cm−1 (Fig. 5A). No clinoenstatite phase (C2/c) presence was detected, which should be visible with an additional peak around 280 cm−149. Characteristic Raman lines for forsterite in the Ribbeck meteorites represent a typical pure forsterite spectrum50 (Fig. 5B). The primary peaks are 824, 856, 881, 918, and 963 cm−1. Active phonons below 500 cm−1 are the lattice modes (Raman-active phonons), where Mg2 translations are mixed with SiO4 translations and rotations51. The peak at 824 cm−1 is related to the Si-O stretching, 856 and 963 cm−1 to Si-O stretching and SiO4tetrahedra breathing. Peaks at 881 and 918 cm−1 are connected to v3vibration mode. Sharp peaks at 918 and 963 cm−1 indicate that three analyzed forsterite crystals have no Fe impurities52. The Feldspar (albite) spectrum is typical for Na-rich plagioclases (Fig. 5C). Characteristic Raman lines are located at 155, 168, 222, 285, 472, and 508 cm−1. The first three overlap with several more, which is most likely the result of the previous annealing of feldspar (due to metamorphism), which was already reported for albite53 and can be connected with tetrahedral cage-ring rotation. The peak at 222 cm−1 is well defined in two samples, which is most likely a pure albite spectrum; however, the disappearance of the peak at 155 and the appearance of another peak at 168 cm−1 in three different spectra is most likely connected with the Ca-substitution in feldspar, which was already mentioned in the EDS analysis. These changes in the Raman spectra analysis had already been deeply studied54; thus, we came to a similar conclusion. Another peak at 285 cm−1is assigned to Na(Ca) displacements perpendicular to the axis and shear deformations of the tetrahedral cage along the a-c direction55. The peak at 472 cm−1 presence is connected with the motions including Na(Ca)-coordination expansion with tetrahedral ring compression in the a-b plane. The peak at 508 cm−1 is connected with the vibration of the tetrahedral cages along the c-axis53. When modeled, McKeown connects it with compression-expansion motions in a four-membered tetrahedral ring and Na(Ca) translation along the a axis55. It is also known to be not affected by any substitution. What is more, these three peaks were noticed to be broader after the annealing. The additional small peak at ~ 575 cm−1 is connected with the tetrahedral deformation. Additionally, the presence of brezinaite and troilite was confirmed by Raman spectroscopy (and possibly daubréelite, see the supplementary materials).

Characteristic Raman lines obtained from Ribbeck meteorite fragments, which correspond to (A) Enstatite (Fe-Free) - green, (B) Forsterite - blue and (C) Feldspars (albite) - grey. The Enstatite and Forsterite crystals are similar to each other, while feldspars differ a little, which is caused most likely by their different chemical composition (Na/Ca substitutions).

Magnetic measurements

The magnetic properties were studied for two samples taken from two different places of the meteorite, both taken from its inside part. The first contained mainly dark fragments (brecciated part, sample A), and the second contained mainly white fragments (enstatite crystal, sample B) of the meteorite. Magnetic field-dependent magnetization M(H) measurements were performed in the 2 to 300 K temperature range. In the case of sample A, the coercive field increases from 443 to 586 Oe when the temperature is changed from 2 to 10 K, respectively (Fig. 6A). A further increase in temperature results in a monotonic decrease of the coercive field to 367 Oe at 300 K. This behavior can be explained by the presence of Fe, Cr, Ti, and Mn sulphides (likely troilite, which coercive field in 5 K is estimated to be 560 Oe)56, and additionally, FeNi-based (kamacite) metallic particles57, which are scattered all over the meteorite in low concentration (less than 1%, see SEM picture on Fig. 6B). Sample A’s remanence magnetization (at zero field) is very low and decreases with temperature from 0.016 to 0.011 Am2 kg−1 at 2 and 300 K, respectively. These values are in a range of, for instance, Neuschwanstein enstatite chondrite (0.008–0.01 Am2 kg−1), whose magnetic properties were determined mainly by the presence of FeNi (kamacite)58. Temperature dependence of the magnetization of sample A is shown in Fig. 6B. The Magnetization versus Temperature M(T) curves were collected in Zero field cooling (ZFC) and field cooling (FC) mode at 10 kOe. Both curves almost overlap. However, there is a visible distinct in the FC magnetic behavior at 115–120 K (main peak at Tt = 117 K). Sample B shows a similar magnetic nature. Although, as seen in M(H) measurements, the coercive field reaches much lower values (Fig. 6C). At low temperatures, in a range of 2 to 10 K, the value of the coercive field increases from 214 to 263 Oe, respectively. Above the peak temperature, the coercive field decreases to 157 Oe at 300 K. The remanence of sample B is slightly lower from sample A and decreases from 0.011 to 0.007 Am2 kg−1 when the temperature increases from 2 to 300 K, respectively, and could be connected with kamacite presence, as mentioned in previous sample58. The lower coercive field values and remanence values in the brecciated part, when compared to the enstatite crystal, can be associated with fewer sulphides and metallic particles (see SEM picture in Fig. 6D) and possibly their different composition. Moreover, this sample has more of a paramagnetic behavior than sample A, as seen on the M(H) curve. No transition at about ~ 120 K is present, which was the case for sample A in the M(T) measurement (Fig. 6D).

Magnetic measurements of the Ribbeck meteorite: Hysteresis loop magnetization vs. external magnetic field of (A) darker (brecciated, with more sulphides) and (C) white fragments (enstatite), and magnetic moment vs. temperature of (B) darker and (D) white fragments, obtained with SQUID. Magnetization vs. temperature measurement was performed with an external magnetic field of 10 kOe.

Discussion

Most of the Ribbeck meteorites are rounded fragments, oriented (with flow lines), and partly (or fully) covered with transparent to white, cracked fusion crust (which changes to brownish in some areas) (Fig. 1). Aubrites are known to be very fragile59; therefore, many pieces were broken. By an outlook, this meteorite looks almost identical (e.g., color, crust, enstatite to plagioclase ratio, crystalite sizes) to the aubrite fall in 2021 in Morocco – Tiglit60. Similarities in the chemical composition of Ribbeck’s meteorite and different aubrites, such as Aubres, Norton County, and especially Bishopville, were also recently confirmed11. In opposition to the Shallowater aubrite61, it is brecciated. Specifically, it is a coarse-grained achondritic breccia, composed mostly of macroscopic (~ 1 cm) enstatite crystals, smaller (millimetric-size) feldspars (albite), and forsterite (up to 2 mm) crystals. Its brecciation proves it went through metamorphic evolution (such as impacting). The elementary cell of orthoenstatite crystals observed in the Ribbeck meteorite is smaller than those known on Earth (a = 18.23, b = 8.84, and c = 5.19 Å), and similar to the enstatite measured in situ with a pressure of 5.72 GPa and a temperature of 1473 K62. Moreover, studies in situ for even higher pressures confirm that the elementary cells are getting even smaller with the constant presence of a high pressure63,64. One has to remember that impurities can also have a notable effect on the elementary cell parameter. No presence of proto enstatite (high-temperature phase) or high or low clinoenstatite (high/low-pressure phases) was detected, which suggests that according to the phase diagram (Fig. 1in the ref65). , the temperature of formation was above 1120 K, and the pressure ranged from 0.5 to 6 GPa. The Raman spectrum of all enstatite crystals is similar to those obtained for decompressed clinoenstatite in laboratory66. These results are also consistent with a recently published paper, where the white and dark lithology of the Ribbeck meteorite were also tested by Raman spectroscopy67. Raman spectra lines of both ortho- and clinopyroxenes are very similar, but in Ribbeck’s enstatite crystals match almost perfectly with all peaks. Slight shifts and a broadening are most likely caused by structural damage (local metamorphism on AuPB) and according to EDS, possibly a small differences in the chemical composition. Shock processes can be reliable for short-range lattice disruption, and it is connected directly to Raman response – the higher the intensity of shock processes, the broader Raman spectra peaks of the crystal68. One can conclude the Ribbeck meteorite is consistent with the S2-S4 shock stage in enstatite, which is similar to most known brecciated aubrites shock stage69. Additionally, the Raman data obtained in this work for albitie crystals are consistent with the literature70 for S1-S3 shock stage (less than 20 GPa), therefore, we report the shock stage of S2-S3 for the Ribbeck meteorite.

What is more, the presence of sulphides such as oldhamite, troilite, alabandite, and brezinaite was confirmed. Their size was primarily in the micrometric/nanometric scale (Figs. 3 and 4). Small metallic nodules (Fig. 4D) built of FeNi (Fe99−xNix(x = 1–7)) were also present. Oldhamite (and other sulphides found in aubrites) is known for its instability in terrestrial conditions, which was proposed to be the case for its absence or low quantity of this mineral phase in laboratory samples71. That was also the case of the absence of characteristic spectra of oldhamite (0.5-µm band, which is observed in E-type asteroids) in aubrite-type meteorites. The origin of the Ribbeck meteorite is most likely igneous, proven by the depletion of metals and their sulphides while containing a high amount of silicates (which also marks the differentiation). Nevertheless, impacting and igneous origins can have similar cooling rates and often share very similar textural remarks72. The brecciation for aubrites is proposed to have taken place in the first 4 Myr of the Solar System formation73. Highly reductive conditions cause some lithophile elements to behave as siderophiles or chalcophiles. For instance, Ca, Fe, Cr, Mn, and Ti are cumulated in sulphides, and Fe, Ni, and partially Si are cumulated in the metallic part. Most REEs in aubrites are cumulated in the oldhamite mineral74, so in this case, REEs also act chalcophilic. It must also be mentioned that oldhamite presence and diopside absence can be explained by high S fugacity and very low O fugacity, which limits the stability of diopside in favor of oldhamite75. However, in Ribbeck, small „traces” of diopside were recently reported11. When taking a closer look into sulphides, for daubréelite to be exsolved from troilite, the temperature has to be lower than 600 °C. In the case of niningerite, the temperature has to be below 500 °C76. In the case of the Ribbeck meteorite, no such exsolvation has been observed, which agrees with recently published papers. It emphasizes the value of freshly collected samples for scientific research. They provide researchers with the most accurate and up-to-date information, allowing for more precise analysis and results. The sulphides found in aubrites, such as alabandite, daubréelite, brezinaite, niningerite, wassonite/heideite, and (especially) oldhamite, are those considered very susceptible for weathering in terrestrial conditions.

The average mass-normalized magnetic susceptibility (χm) of Ribbeck meteorite pieces was tested recently11. The mean value was estimated to be logχm = 3.13, which lies in the proposed magnetic classification range for achondrites77, and other aubrites78. Observed aubrites’ logχmvaries from less than 2 (LAP 03719, anomalous aubrite) to almost 5 (Shallowater, unbrecciated aubrite)78. The content of ferromagnetic metal (mostly kamacite) was in a range of 0.1–0.6 wt%. As an example, the magnetic behavior of the Ribbeck meteorite is similar to experimentally obtained komatiites (ultramafic extrusive rock)79. Komatiites are highly enriched with Mg and depleted with Si, K, and Al, which both agree with known aubrites’ composition80. Nevertheless, speaking of komatiites, in aubrites, the high abundance of sulphur and low amounts of iron differs from any basaltic rocks found on Earth or even on the Moon81.

According to the literature, the coercive field exceeding 500 Oe could be caused by the preferential alignment of kamacite crystals, and the possible presence of ordered FeNi (tetrataenite) grains82. The presented noticeable change in the FC magnetic behavior of brecciated fragment at ~ 117 K can be explained by Fe-bearing sulphide phase evolution, which similarities can be found in literature, as an example - for troilite and daubréelite56,58, which both were confirmed to be present in the Ribbeck meteorite. The magnetic transition could be mistakenly taken for the Verwey transition in magnetite83. However, no iron oxides were detected in the analyzed pieces. Still, signs of weathering of sulphides in the Ribbeck meteorite were detected recently in different work11. The presence of ferromagnetic pyrrhotite in the Ribbeck meteorite could also not be excluded84.

Conclusions and summary

2024 BX1 (SAR2736) was an eighth observed asteroid, detected shortly before the impact. The investigations of the meteoritic matter confirmed that the Ribbeck meteorite belongs to a rare aubrite-type achondrite group. XRD and Raman spectra investigations show that it mainly comprises Fe-free enstatite, forsterite, and Na-rich feldspar (albite). EDS investigations additionally reveal that these three main phases are assisted by sulphides, most of which are not to be found on Earth. Troilite, brezinanite (daubréelite/zolenskyite), alabandite, oldhamite, and wassonite/heideite (Cr). Next, metallic phases such as kamacite (enriched with Si) were often observed with a close sulphides neighborhood. Schreibersite crystals embedding kamacite and troilite crystals were detected. These mineral phases are evidence of a highly reductive environment (depleted in fO2), with ΔIW reaching values as low as −5 to −7. That caused many elements that behave as lithophiles in Earth’s conditions to switch their character to chalcophiles or siderophiles. These are primarily metals such as Ca, Ti, Cr, and Mn (and partially Si). We assume that CrFe alloys may be a product of atmospheric entry melting, which caused the sulphur to evaporate. Magnetic measurements show the high value of the coercive field of the dark-part sample (over 500 Oe); however, the magnetic moment is relatively low (0.1–0.3 Am2 kg−1), which we connect to the preferential crystallographical alignment of suplhides and magnetic particles and the possible presence of tetrataenite phase. The magnetic transition was found in M(T) measurements, similar to troilite and daubréelite transition at low temperatures, with the highest magnetic moment peak at ~ 120 K, which would be another confirmation that sulphides and metallic FeNi are primarily responsible for the magnetic behavior of the Ribbeck meteorite. One of the potential sources (AuPB) of aubrite-brecciated type meteorites is 3103 Eger or 2867 Steins. One has to remember, these meteorites (and possibly these asteroids) may also originate from the proto-Mercury, from which the mantle was blasted off due to a massive impact in the past, and the aubrite-type meteorites are just small pieces of its previous mantle in early Solar System Formation.

Methods

X-ray diffraction experiments were performed on Empyrean (Panalytical) X-ray equipment, working on a Cu Kα (45 kV and 40 mA) lamp. Measurements were conducted on pieces of the Ribbeck meteorite, placed without crushing on a zero background silicon holder. Samples were repositioned and re-measured to increase the statistical contribution of all the crystalline phase samples.

Measurements of Raman scattering were conducted using a micro-Raman spectrometer from Renishaw, which includes a confocal microscope by Leica. The analysis was carried out in a backscattering setup, achieving a spectral resolution superior to 1.0 cm −1. The incident light was unpolarized and the detector used for capturing the light did not incorporate any polarization filters. The spectra resulting from Raman scattering were generated using a 488 nm laser source. This beam was concentrated onto the sample areas using a microscope objective that magnifies 50 times, featuring a numerical aperture of 0.4.

The morphology and chemical composition were studied with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using the HITACHI S-3700 N variable-pressure electron microscope with a tungsten filament, equipped with the ThermoScientific® Energy Dispersive Spectrometer (EDS) detector and the Noran System 7 (NSS) analytical software. Minerals were located and identified using BSE mode at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV, a working distance of 10 mm, and a vacuum of 25 Pa. Semi-quantitative EDS X-ray microanalysis was performed using EDS spot analysis with an acquisition time of 80 s and maximum process time to achieve the best resolution of peaks in spectra. SEM-EDS was performed at the Faculty of Geographical and Geological Sciences (Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań).

Magnetic measurements were performed on a SQUID magnetometer, MPMS-XL (Quantum Design, Inc.). The temperature dependence of the magnetization was measured in the temperature range 2–350 K in an external field of 1 kOe, 5 kOe, and 10 kOe. The magnetization curves as a function of the magnetic field were measured in the field range of ± 25 kOe at a temperature range from 2 K to 300 K. Measurements were performed on two selected pieces, both taken from the inside of the meteorite – dark one, which weight 7.97 mg and white one, which weight 13.63 mg (See SEM pic. On Fig. 6B and D).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Anders, E. Meteorites and the early solar system. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 9, 1–34 (1971).

Nicklas, R. W., Day, J. M. D., Gardner-Vandy, K. G. & Udry, A. Early silicic magmatism on a differentiated asteroid. Nat. Geosci. 15, 696–699 (2022).

Koeberl, C. & Cassidy, W. A. Differences between Antarctic and non-antarctic meteorites: an assessment. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 55, 3–18 (1991).

Dudorov, A. E. & Eretnova, O. V. The rate of Falls of meteorites and bolides. Sol Syst. Res. 54, 223–235 (2020).

Anders, E. Origin, age, and composition of meteorites. Space Sci. Rev. 3, 583–714 (1964).

Cunningham, C. J., Marsden, B. G. & Orchiston, W. Giuseppe Piazzi: the controversial Discovery and loss of Ceres in 1801. J. Hist. Astron. 42, 283–306 (2011).

Zolensky, M. et al. Mineralogy and petrography of the Almahata Sitta Ureilite. Meteorit Planet. Sci. 45, 1618–1637 (2010).

Horstmann, M. & Bischoff, A. The Almahata Sitta polymict breccia and the late accretion of asteroid 2008 TC3. Geochemistry 74, 149–183 (2014).

Bischoff, A. et al. Asteroid 2008 TC 3, not a polymict ureilitic but a polymict C1 chondrite parent body? Survey of 249 Almahata Sitta fragments. Meteorit Planet. Sci. 57, 1339–1364 (2022).

Spurny, P., Borovicka, J., Shrbeny, L., Hankey, M. & Neubert, R. Atmospheric entry and fragmentation of small asteroid 2024 BX1: Bolide trajectory, orbit, dynamics, light curve, and spectrum. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202449735

Bischoff, A. et al. Cosmic pears from the Havelland (Germany): Ribbeck, the twelfth recorded aubrite fall in history. Meteorit Planet. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1111/maps.14245 (2024).

Krot, A. N., Keil, K., Scott, E. R. D., Goodrich, C. A. & Weisberg, M. K. Classification of Meteorites and Their Genetic Relationships. in Treatise on Geochemistry 1–63Elsevier, (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-095975-7.00102-9

Ray, S., Garvie, L. A. J., Rai, V. K. & Wadhwa, M. Correlated iron isotopes and silicon contents in aubrite metals reveal structure of their asteroidal parent body. Sci. Rep. 11, 22552 (2021).

Wilbur, Z. E. et al. The effects of highly reduced magmatism revealed through aubrites. Meteorit Planet. Sci. 57, 1387–1420 (2022).

Lorenz, C. A., Ivanova, M. A., Brandstaetter, F., Kononkova, N. N. & Zinovieva, N. G. Aubrite Pesyanoe: clues to composition and evolution of the enstatite achondrite parent body. Meteorit Planet. Sci. 55, 2670–2702 (2020).

Rubin, A. E., Scott, E. R. D. & Keil, K. Shock metamorphism of enstatite chondrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 61, 847–858 (1997).

Wilson, L. & Keil, K. Consequences of explosive eruptions on small solar system bodies: the case of the missing basalts on the aubrite parent body. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 104, 505–512 (1991).

Scott, E. R. D., Haack, H. & Love, S. G. Formation of mesosiderites by fragmentation and reaccretion of a large differentiated asteroid. Meteorit Planet. Sci. 36, 869–881 (2001).

Lorenzetti, S. et al. History and origin of aubrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 67, 557–571 (2003).

Zhu, K. et al. Tracing the origin and core formation of the enstatite achondrite parent bodies using cr isotopes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 308, 256–272 (2021).

Keil, K. Enstatite achondrite meteorites (aubrites) and the histories of their asteroidal parent bodies. Geochemistry 70, 295–317 (2010).

Steenstra, E. S. & van Westrenen, W. Geochemical constraints on core-mantle differentiation in Mercury and the aubrite parent body. Icarus 340, 113621 (2020).

Wolf, R., Ebihara, M., Richter, G. R. & Anders, E. Aubrites and diogenites: Trace element clues to their origin. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 47, 2257–2270 (1983).

Rubin, A. E. Shock and annealing in aubrites: implications for parent-body history. Meteorit Planet. Sci. 50, 1217–1227 (2015).

Lodders, K., Palme, H. & Wlotzka, F. Trace elements in mineral separates of the Peña Blanca Spring aubrite: implications for the evolution of the aubrite parent body. Meteoritics 28, 538–551 (1993).

Righter, K., Sutton, S. R., Danielson, L., Pando, K. & Newville, M. Redox variations in the inner solar system with new constraints from Vanadium XANES in spinels. Am. Mineral. 101, 1928–1942 (2016).

Okada, A., Keil, K., Taylor, G. J. & Newsom, H. Igneous history of the Aubrite parent asteroid: evidence from the Norton County Enstatite Achondrite. Meteoritics 23, 59–74 (1988).

Herndon, J. M. & Rudee, M. L. Thermal history of the Abee enstatite chondrite. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 41, 101–106 (1978).

Haba, M. K., Wotzlaw, J. F., Lai, Y. J., Yamaguchi, A. & Schönbächler, M. Mesosiderite formation on asteroid 4 Vesta by a hit-and-run collision. Nat. Geosci. 12, 510–515 (2019).

Greenwood, R. C., Franchi, I. A., Jambon, A., Barrat, J. A. & Burbine, T. H. Oxygen isotope variation in Stony-Iron Meteorites. Sci. (80-). 313, 1763–1765 (2006).

Consolmagno, G. J. & Drake, M. J. Composition and evolution of the eucrite parent body: evidence from rare earth elements. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 41, 1271–1282 (1977).

Casanova, I., Keil, K. & Newsom, H. E. Composition of metal in aubrites: constraints on core formation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 57, 675–682 (1993).

Elkins-Tanton, L. T. et al. Distinguishing the origin of asteroid (16) psyche. Space Sci. Rev. 218, 17 (2022).

Dibb, S. D., Bell, J. F. & Garvie, L. A. J. Spectral reflectance variations of aubrites, metal-rich meteorites, and sulfides: implications for exploration of (16) psyche and other spectrally featureless asteroids. Meteorit Planet. Sci. 57, 1570–1588 (2022).

Nakamura, T. et al. Formation and evolution of carbonaceous asteroid Ryugu: Direct evidence from returned samples. Science 379, eabn8671 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn8671.

Cantillo, D. C. et al. Laboratory Spectral characterization of Ribbeck Aubrite: Meteorite Sample of Earth-impacting Near-Earth asteroid 2024 BX1. Planet. Sci. J. 5, 138 (2024).

Ebel, D. S. & Alexander, C. M. O. Equilibrium condensation from chondritic porous IDP enriched vapor: implications for Mercury and enstatite chondrite origins. Planet. Space Sci. 59, 1888–1894 (2011).

Sprague, A. L., Kozlowski, R. W. H., Witteborn, F. C., Cruikshank, D. P. & Wooden, D. H. Mercury: evidence for Anorthosite and Basalt from mid-infrared (7.3–13.5 µm) spectroscopy. Icarus 109, 156–167 (1994).

Nittler, L. R. & Weider, S. Z. The Surface composition of Mercury. Elements 15, 33–38 (2019).

Charlier, B., Grove, T. L. & Zuber, M. T. Phase equilibria of ultramafic compositions on Mercury and the origin of the compositional dichotomy. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 363, 50–60 (2013).

Zolotov, M. Y. et al. The redox state, FeO content, and origin of sulfur-rich magmas on Mercury. J. Geophys. Res. Planet. 118, 138–146 (2013).

Stockstill-Cahill, K. R., McCoy, T. J., Nittler, L. R., Weider, S. Z. & Hauck, S. A. Magnesium-rich crustalcompositions on Mercury: Implications for magmatism from petrologic modeling. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 117, E00L15 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1029/2012JE004140.

Hayden, T. S. et al. Detection of apatite in ferroan anorthosite indicative of a volatile-rich early lunar crust. Nat. Astron. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-023-02185-5 (2024).

Denevi, B. W. et al. The evolution of Mercury’s Crust: A Global Perspective from MESSENGER. Sci. (80-). 324, 613–618 (2009).

McCord, T. B., Adams, J. B. & Johnson, T. V. Asteroid Vesta: spectral reflectivity and compositional implications. Sci. (80-). 168, 1445–1447 (1970).

De Sanctis, M. C. et al. Spectroscopic characterization of Mineralogy and its Diversity Across Vesta. Sci. (80-). 336, 697–700 (2012).

Consolmagno, G. J. et al. Is Vesta an intact and pristine protoplanet? Icarus 254, 190–201 (2015).

Ma, C., Rubin, A. E. & Zolenskyite FeCr2S4, a new sulfide mineral from the Indarch meteorite. Am. Mineral. 107, 1030–1033 (2022).

Akashi, A. et al. Orthoenstatite/clinoenstatitephase transformation in MgSiO3 at high-pressure and high-temperature determined by in situ X-ray diffraction:Implications for nature of the X discontinuity. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 114, B04206 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JB005894.

Stangarone, C., Böttger, U., Bersani, D., Tribaudino, M. & Prencipe, M. Ab initio simulations and experimental Raman spectra of mg 2 SiO 4 forsterite to simulate Mars surface environmental conditions. J. Raman Spectrosc. 48, 1528–1535 (2017).

McKeown, D. A., Bell, M. I. & Caracas, R. Theoretical determination of the Raman spectra of single-crystal forsterite (Mg2SiO4). Am. Mineral. 95, 980–986 (2010).

Ishibashi, H., Arakawa, M., Yamamoto, J. & Kagi, H. Precise determination of Mg/Fe ratios applicable to terrestrial olivine samples using Raman spectroscopy. J. Raman Spectrosc. 43, 331–337 (2012).

Tribaudino, M., Gatta, G. D., Aliatis, I., Bersani, D. & Lottici, P. P. <scp > Al—Si ordering in albite: a combined single-crystal < scp > X ‐ray diffraction and < scp > raman spectroscopy study</scp >. J. Raman Spectrosc. 49, 2028–2035 (2018).

Freeman, J. J., Wang, A., Kuebler, K. E., Jolliff, B. L. & Haskin, L. A. CHARACTERIZATION OF NATURAL FELDSPARS BY RAMAN SPECTROSCOPY FOR FUTURE PLANETARY EXPLORATION. Can. Mineral. 46, 1477–1500 (2008).

McKeown, D. A. Raman spectroscopy and vibrational analyses of albite: from 25 C through the melting temperature. Am. Mineral. 90, 1506–1517 (2005).

Čuda, J. et al. Mössbauer study and magnetic measurement of troilite extract from Natan iron meteorite. AIP Conf. Proc. 1489, 145–153 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4759483.

Pechersky, D. M., Markov, G. P., Tsel’movich, V. A. & Sharonova, Z. V. Extraterrestrial magnetic minerals. Izv. Phys. Solid Earth. 48, 653–669 (2012).

Kohout, T. et al. Low-temperature magnetic properties of the Neuschwanstein EL6 meteorite. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 261, 143–151 (2007).

Guy Consolmagno, S. J. & Britt, D. T. Meteoritical evidence and constraints on asteroid impacts and disruption. Planet. Space Sci. 52, 1119–1128 (2004).

Gattacceca, J. et al. The Meteoritical Bulletin, 111. Meteorit Planet. Sci. 58, 901–904 (2023).

Keil, K. et al. The shallowater aubrite: evidence for origin by planetesimal impacts. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 53, 3291–3307 (1989).

Shinmei, T., Tomioka, N., Fujino, K., Kuroda, K. & Irifune, T. In situ X-ray diffraction study of enstatite up to 12 GPa and 1473 K and equations of state. Am. Mineral. 84, 1588–1594 (1999).

Periotto, B., Balic-Zunic, T., Nestola, F., Katerinopoulou, A. & Angel, R. J. Re-investigation of the crystal structure of enstatite under high-pressure conditions. Am. Mineral. 97, 1741–1748 (2012).

Zhang, L., Meng, Y. & Mao, W. L. Effect of pressure and composition on lattice parameters and unit-cell volume of (fe,mg)SiO3 post-perovskite. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 317–318, 120–125 (2012).

Clément, M., Padrón-Navarta, J. A., Tommasi, A. & Mainprice, D. Non-hydrostatic stress field orientation inferred from orthopyroxene (Pbca) to low-clinoenstatite (P21/c) inversion in partially dehydrated serpentinites. Am. Mineral. 103, 993–1001 (2018).

Lin, C. C. Pressure-induced polymorphism in enstatite (MgSiO3) at room temperature: clinoenstatite and orthoenstatite. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 65, 913–921 (2004).

Dudek, M., Grabarczyk, J., Jakubowski, T., Zaręba, P. & Karczemska, A. Raman Spectroscopy investigations of Ribbeck Meteorite. Mater. (Basel). 17, 5105 (2024).

Miyamoto, M. & Ohsumi, K. Micro Raman spectroscopy of olivines in L6 chondrites: evaluation of the degree of shock. Geophys. Res. Lett. 22, 437–440 (1995).

Rubin, A. E. Impact features of enstatite-rich meteorites. Geochemistry 75, 1–28 (2015).

Fritz, J., Assis Fernandes, V., Greshake, A., Holzwarth, A. & Böttger, U. On the formation of diaplectic glass: shock and thermal experiments with plagioclase of different chemical compositions. Meteorit Planet. Sci. 54, 1533–1547 (2019).

Clark, B. E. et al. E-type asteroid spectroscopy and compositional modeling. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 109, E02001 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1029/2003JE002200.

Osinski, G. R. et al. Igneous rocks formed by hypervelocity impact. J. Volcanol Geotherm. Res. 353, 25–54 (2018).

Ray, S., Garvie, L. A. J., Rai, V. K. & Wadhwa, M. Publisher correction: correlated iron isotopes and silicon contents in aubrite metals reveal structure of their asteroidal parent body. Sci. Rep. 11, 23906 (2021).

Floss, C., Strait, M. M. & Crozaz, G. Rare earth elements and the petrogenesis of aubrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 54, 3553–3558 (1990).

Fogel, R. On the significance of diopside and oldhamite in enstatite chondrites and aubrites. Meteorit Planet. Sci. 32, 577–591 (1997).

Udry, A. et al. Reclassification of four aubrites as enstatite chondrite impact melts: potential geochemical analogs for Mercury. Meteorit Planet. Sci. 54, 785–810 (2019).

Smith, D. L., Ernst, R. E., Samson, C. & Herd, R. Stony meteorite characterization by non-destructive measurement of magnetic properties. Meteorit Planet. Sci. 41, 355–373 (2006).

Rochette, P. et al. Magnetic classification of stony meteorites: 3. Achondrites. Meteorit Planet. Sci. 44, 405–427 (2009).

Shibuya, T. et al. Hydrogen-rich hydrothermal environments in the Hadean ocean inferred from serpentinization of komatiites at 300°C and 500 bar. Prog Earth Planet. Sci. 2, 46 (2015).

Arndt, N. Komatiites, kimberlites, and boninites. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 108, 2293 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JB002157.

Weider, S. Z. et al. Chemical heterogeneity on Mercury’s surface revealed by the MESSENGER X-Ray spectrometer. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 117, E00L05 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1029/2012JE004153.

Gattacceca, J. et al. Metal phases in ordinary chondrites: magnetic hysteresis properties and implications for thermal history. Meteorit Planet. Sci. 49, 652–676 (2014).

Piekarz, P., Parlinski, K. & Oleś, A. M. Mechanism of the Verwey Transition in Magnetite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 156402 (2006).

Dekkers, M. J. Magnetic properties of natural pyrrhotite part I: Behaviour of initial susceptibility and saturation-magnetization-related rock-magnetic parameters in a grain-size dependent framework. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 52, 376–393 (1988).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Prof. Bogusław Mróz and Dr. Grzegorz Nowaczyk from the NanoBioMedical Centre for their valuable assistance in the creation of this manuscript. Authors also want to mention, that they greatly appreciate the assistance and excellent work of the reviewers: prof. Xiaojia Zeng and prof. Jörg Fritz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization was done by M.K. and E.C., the methodology by M.K., D.M., and E.C., investigations was performed by M.K., D.M., K.Z., I.I., A.M. and E.C., visualization was performed by M.K. K.Z. and E.C., supervision was done by A.M., and E.C., writing of original draft was done by M.K., and all authors contributed into revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kołodziej, M., Michalska, D., Załęski, K. et al. A closer look into the structure and magnetism of the recently fallen meteorite Ribbeck. Sci Rep 15, 6866 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90383-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90383-8