Abstract

Skin cancer is widespread and can be potentially fatal. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), it has been identified as a leading cause of mortality. It is essential to detect skin cancer early so that effective treatment can be provided at an initial stage. In this study, the widely-used HAM10000 dataset, containing high-resolution images of various skin lesions, is employed to train and evaluate. Our methodology for the HAM10000 dataset involves balancing the imbalanced dataset by augmenting images followed by splitting the dataset into train, test and validation set, preprocessing the images, training the individual models Xception, InceptionResNetV2 and MobileNetV2, and then combining their outputs using fuzzy logic to generate a final prediction. We examined the performance of the ensemble using standard metrics like classification accuracy, confusion matrix, etc. and achieved an impressive accuracy of 95.14% and the result demonstrates the effectiveness of our approach in accurately identifying skin cancer lesions. To further assess the efficiency of the model, additional tests have been performed on the DermaMNIST dataset from the MedMNISTv2 collection. The model performs well on the dataset and transcends the benchmark accuracy of 76.8%, achieving 78.25%. Thus the model is efficient for skin cancer classification, showcasing its potential for clinical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Skin cancer typically arises due to the abnormal growth of new skin cells — which might be caused due to direct exposure to UV rays from sunlight. It could be also caused due to similar family history. These cells can sometimes be cancerous in nature. Lack of early diagnosis of skin cancer might result in spreading of cancer to other regions of the body as well1. The most prevalent forms of skin cancer include — Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC), Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC) and malignant melanoma. Studies indicate skin cancer accounts only about less than 1% in India2. Skin cancer occurrence is fairly lower compared to the western regions of the world, although the absolute number of cases in India is significant due to India being the most populous country in the world. However, in the USA, over 1 million cases of SCC and 4.3 million cases of BCC are discovered each year. Early detection of skin cancer is crucial for improving outcomes and is associated with a 99% overall survival rate3,4.

Trained medical professionals, including dermatologists, employ various treatments such as chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiation therapy, or surgery to eliminate cancer cells in the skin. Dermoscopy, which involves using a dermatoscope to examine skin lesions, aids in distinguishing between benign and malignant lesions. Additionally, advanced imaging techniques like MRI, CT scans, optical coherence tomography and reflectance confocal microscopy can provide detailed images of skin layers5,6.

However, medical procedures for diagnosing skin cancer, including biopsy processing, are challenging and time-consuming7,8. Additionally, traditional skin cancer diagnosis methods have several challenges, as it relies on interpreting various visual indicators including lesion morphology, distribution across the body, color, scaling and lesion arrangement. The complexity increases when each of these indicators is considered independently, making the recognition process intricate. The methods to diagnose skin cancer are limited as it requires having a substantial level of expertise to differentiate between lesions accurately9.

In recent times, medical professionals opt for image based Computer Aided Diagnosis (CAD) systems to analyse skin lesions, helping dermatologists to determine the likelihood of having cancer, to detect cancer in their early stages itself. However, CAD systems utilise image processing techniques to analyse skin lesions, and given the existence of several variants of cancer, this type of classification is highly non-linear10.

This is where deep learning models prove to be robust in detecting skin cancer in early phases itself. Our proposed work suggests the use of a fuzzy based ensemble of Xception11, InceptionResNetV212 and MobileNetV213 models to seamlessly identify traces of skin cancer in the body. We have pre-processed the HAM1000014 dataset and furthermore also implemented data augmentation measures and regularisation techniques as well to boost the accuracy. The fuzzy based ensemble technique reduces the variance of the model and takes into account some of the imprecise information and noise in the skin lesion images, which is possible due to the presence of inaccurate instances of information. Additionally, our model has outperformed several similar publicly available work on the HAM10000 dataset14.

Figure 1 displays the flow diagram of our proposed model pipeline. The following key-points summarize and highlight our proposed work —.

-

I.

We propose a new model which is a fuzzy based ensemble of Xception11, InceptionResNetV212 and MobileNetV213 models by utilizing images of several classes of skin lesions.

-

II.

In our proposed work, we have primarily tested the effectiveness of our fuzzy ensemble model on an augmented HAM10000 dataset. Additionally, the proposed model is also tested on DermaMNIST dataset taken from MedMNISTv2 collection15.

-

III.

Our proposed work achieves outstanding training as well as test accuracies, displaying robustness in detecting unseen instances of melanoma.

Related study

Alam et al. propose a system based on InceptionV3, RegNetY-320 and AlexNet deep learning models for differentiating skin lesions with an efficient performance. In addition to this, they also resolved the data imbalance issue using data augmentation. They classified skin cancer images with an accuracy, F1 score16, and ROC17 curve value 91%, 88.1% and 0.953.

Anand et al. employ a biomedical image analysis method using different variants of ResNet, i.e. ResNet18, ResNet50 and ResNet101. It obtained accuracy values of 0.96, 0.90, 0.89 and 0.86 using ResNet101, ResNet50 and ResNet18 models respectively18.

Arshad et al. performed their experiments on an augmented HAM10000 dataset. They reported an accuracy of 64.36% with ResNet-50 and 49.98% with ResNet-101. However, using the augmented dataset, the accuracy significantly improved to 95% through feature fusion and 91.7% through feature selection19.

Lariba et al. used a transfer learning method which applied ImageSet-based Inception V3, ResNet50, Xception11 and DenseNet network models to achieve skin disease image data classification. The models InceptionV3, ResNet50 and DenseNet201 and all of them achieved a training accuracy of 95%. After preprocessing, these improved 3 models achieved highest accuracy of 86.91% for DenseNet compared with the other contender model ResNet50 which achieved highest accuracy of 83.26%20.

Datta et al. employed a soft-attention mechanism to enhance significant features in the skin lesion dataset while reducing noise. This approach achieved a precision of 91.6% on the ISIC-2017 dataset. and 93.7% on the HAM10000 dataset21.

Naeem et al.22 presented the DVFNet model that employs a deep feature fusion to improve skin cancer detection in dermoscopy images. The model achieved 98.32% accuracy on the ISIC 2019 dataset by using features from VGG19 and Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) as input to a two-layer neural network. To preprocess images, they used an isotropic diffusion to remove artifacts and noise that considerably enhances features extraction and classification.

Hameed et al.23, authors highlighted the role of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to classify and segment skin lesion using ISIC dataset. Their review indicated a significant utility of CNN-based models in aiding accuracy and speed clinical decision-making, which ranged from binary to multiclass classification with an increase the Can help achieve certain up-to 95% diagnostic efficiency thereby improving diagnostic performance.

Gayatri et al.24 utilised a fine-tuned ResNet-50 model to handle an imbalanced ISIC-2019 dataset targeting the problem of improved classification of skin cancer. With the help of augmented data and focal loss to tackle overfitting, it delivered 98.85% accuracy, precision of 95.52% and recall of 95.93%. In the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), this metric is used to validate and demonstrates increase effectiveness even for multi-class image data.

Velaga et al.25 proposed to overcome the limitations of accuracy and efficiency when detecting skin cancer. They preprocessed the HAM10000 dataset and trained different models, such as Random Forest with which they achieved successful classification results. Notably, the Random Forest model outperformed all other models with a validation accuracy of 95.5% and test accuracy of 95.6%, improving timely diagnosis and prevention efforts in skin cancers.

Tschandl et al.14 addressed the challenges posed by limited and diverse datasets in training neural networks for automated skin lesion diagnosis by releasing the HAM10000 dataset. This dataset comprises over 10,000 dermatoscopic images collected from various sources, ensuring broad coverage of common pigmented skin lesions. The dataset is publicly available via the ISIC archive and is intended to enhance machine learning research by providing a comprehensive benchmark for training and comparing human and machine diagnostic performance.

Yang et al.26 developed a hybrid self-supervised classification algorithm to address challenges like varying target sizes and subtle differences between skin lesion and normal images. By combining discriminative relational reasoning with generative mutual information maximization, they designed a specialized loss function. This generative-discriminative co-training approach achieved a classification accuracy of 82.6% on the DermaMNIST dataset, effectively identifying subtle image differences and learning discriminative features.

Khan et al.27 employed an automated approach, utilizing a novel Deep Saliency Segmentation method that employs a tailored ten-layer CNN. Additionally, they applied a Kernel Extreme Learning Machine (KELM) classifier, achieving accuracies of 98.70%, 95.79%, 95.38% and 92.69% when analyzing the PH2, ISBI 2017, ISBI 2016 and ISBI 2018 datasets respectively.

Srinivasu et al.28 increased classification accuracy by utilising MobileNet V2 model, which is suited to work on lightweight computational devices. Their approach demonstrated robust performance, surpassing other methods with an accuracy exceeding 85%.

Nyugen et al.29 implemented a method that combined deep learning models, including DenseNet, InceptionNet, and ResNet, with soft attention to extract a heat map of primary skin lesions. Experimentation on the HAM10000 dataset showed that InceptionResNetV2 with soft-attention produced 90% accuracy, which by using MobileNetV3Large with Soft-Attention produced an accuracy of 86%.

Ali et al.30 trained EfficientNets B0-B7 models on HAM10000 dataset. They produced performance metrics to determine how capable are the EfficientNet variants to robustly perform imbalanced multiclass classification of skin lesions. Their top performing model, EfficientNet B4, achieved a Top-1 accuracy of 87.91% and F1 score of 87%.

Şengül et al.31 introduced the MResCaps model, an enhancement of the Capsule Network (CapsNet) designed to improve classification accuracy on complex medical images. By integrating residual blocks in a parallel-laned architecture, MResCaps achieved superior performance, with AUC values of 96.25% on DermaMNIST, 96.30% on PneumoniaMNIST, and 97.12% on OrganMNIST-S, outperforming the original CapsNet by 20% on the CIFAR10 dataset.

Hosny et al.32 proposed an inherent deep learning method for classifying seven skin lesions using the HAM10000 dataset. By integrating Explainable AI (X-AI), the model provides visual explanations to help dermatologists trust its decisions, addressing the shortage of skin lesion images and supporting clinical diagnosis with a transparent, second-opinion tool. Alsahafi et al.33. proposed Skin-Net, a 54-layer deep neural network using residual learning for skin lesion classification. The model employs multi-scale filters (3 × 3 and 1 × 1) to extract features at different levels, reducing overfitting and improving performance, incorporating cross-channel correlation, making it less sensitive to background noise. To handle class imbalance, the dataset was transformed into image-weight vectors instead of image-label pairs. Evaluated on ISIC-2019 and ISIC-2020, it achieved 94.65% and 99.05% accuracy respectively, outperforming previous methods. However, its high computational cost limits deployment on microdevices, requiring further optimization. Naguib et al.34 proposed a deep redefined residual network to classify knee osteoarthritis (OA) as uni or bicompartmental using convolutional, pooling, and batch normalization layers for feature extraction from knee X-ray images. Trained on 733 images (331 normal, 205 unicompartmental, 197 bicompartmental), the model achieved 61.81% accuracy and 68.33% specificity. Comparisons with pre-trained CNN models (AlexNet, ShuffleNet, MobileNetV2, DarkNet53, and GoogleNet) using transfer learning showed superior performance of the proposed model. This study aids orthopedic surgeons in diagnosing and classifying knee OA, particularly in remote areas lacking specialized physicians, improving treatment decisions for unicompartmental arthroplasty or total knee replacement.

Kassem et al.35 proposed an explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) framework for pelvis fracture detection, offering a fast and accurate solution for analyzing X-ray images. Designed to assist physicians, especially in emergency settings, the model helps inexperienced radiologists diagnose fractures effectively. Trained on 876 X-ray images (472 fractures, 404 normal), it achieved 98.5% accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and precision. The study highlights the potential of XAI-driven diagnosis in improving fracture detection. Future work could extend the system to classify major pelvis fracture types, including iliac bone, sacrum, and symphysis fractures, enhancing automated orthopedic diagnostics.

Halder et al.36 explored the ViT-Base-Patch16–224 model for classifying diverse 2D biomedical image datasets from MedMNIST, including BloodMNIST, BreastMNIST, PathMNIST, and RetinaMNIST, achieving 97.90%, 90.38%, 94.62%, and 57% accuracy respectively. The model outperformed existing benchmarks, demonstrating strong adaptability and robustness in biomedical image classification. Additionally, this study worked on DermaMNIST, another dataset from MedMNIST, which focuses on skin disease classification. Similar advancements can be applied to skin cancer classification, where capturing fine-grained lesion details is crucial. Naeem et al.37 reviewed state-of-the-art melanoma detection methods, highlighting deep learning techniques like fully convolutional networks, pre-trained models and handcrafted methods. They found that handcrafted approaches often outperform traditional deep learning when combined with segmentation and preprocessing. While large labeled datasets (PH2, ISBI, DermIS) support research, dataset diversity makes comparison difficult. The study emphasizes the need for larger datasets, hyperparameter fine-tuning, and better CNN generalization for dark-skinned individuals. Future work should integrate age, gender, and race to enhance sensitivity, specificity, and overall accuracy in melanoma detection. Riaz et al.38 reviewed federated learning and transfer learning techniques for melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer classification, analyzing their effectiveness across various skin lesion datasets. The study identified six issues in existing systems and suggested nine improvements to enhance performance. The authors proposed a taxonomy of research and outlined future directions, including the use of graph and signal processing techniques to improve skin cancer detection and assist dermatologists in diagnosis.

Naeem et al.39 proposed the SNC_Net model for classifying eight types of skin lesions (AKs, BCCa, SCCa, BKs, DFa, MNi, MELa, and VASn), aiming to address the growing issue of skin cancer. The model utilizes CNN for classification, with HC and Inception v3 for feature extraction from dermoscopy images, and applies the SMOTE Tomek approach to balance the dataset. Grad-CAM is used to provide a heat map, illustrating the model’s decision-making process. The model achieved 97.81% accuracy, 98.31% precision, 97.89% recall, and a 98.10% F1 score. Although the model is effective, its limitation lies in the inability to process camera-captured images. The study suggests that incorporating federated learning could further enhance classification accuracy. Naeem et al.40 proposed a machine learning-based model that identifies gene activity to detect and understand the metastatic nature of prostate cancer (PCA) with high accuracy. The study uncovered genes that can distinguish between localized and metastatic PCA, offering potential as biomarkers and therapeutic targets. The model could also be applied to other types of cancer and clinical issues. This approach provides an alternative to painful biopsies and misleading image scans, though further investigations are needed to validate these results. Ayesha et al.41 proposed the MMF-SCD approach for skin cancer classification using dermoscopic images from the ISIC dataset, achieving 97.6% accuracy and high performance across multiple metrics. By applying data augmentation and transfer learning, the model reduced computational cost and training time. This method can assist specialists and novice physicians in real-time skin cancer diagnosis, enhancing diagnostic accuracy in healthcare settings.

Motivation of our work

Early and precise identification of skin cancer type is essential for effective treatment and improved patient prognosis. While various machine learning models have displayed promising outcomes on many datasets, there’s always a constant push for improvement in real-world scenarios with datasets like HAM1000014 and DermaMNIST from MedMNISTv215 collection. This study focuses on enhancing skin cancer classification accuracy using a fuzzy ensemble methodology. Fuzzy logic offers the ability to handle inherent uncertainties and ambiguities present in medical images. Ensemble methods, on the other hand, combine the strengths of multiple classifiers, leading to more reliable decision-making. Ultimately, this improved accuracy can significantly benefit dermatologists by aiding in faster, more efficient, and less error-prone evaluation of skin lesions. Early and accurate detection can ultimately lead to better patient care and reduced risks associated with skin cancer.

Datasets used in the study

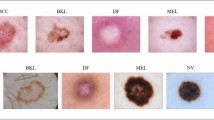

In the research, we utilised the Skin Cancer MNIST : HAM1000014 dataset, an extensive open-source repository of dermatoscopic images of pigmented lesions, gathered from multiple sources, comprising 10,015 images, each labeled with one of seven specific lesion classes such as: basal cell carcinoma (bcc), melanocytic nevi (nv), actinic keratoses & intraepithelial carcinoma (akiec), melanoma (mel), benign keratosis-like lesions (bkl), dermatofibroma (df) and vascular lesions (vasc). Nv represents the largest portion comprising 6705 images, followed by mel with 1113 images and bcc with 514 images. Akiec is represented by 327 images while bkl by 1099 images. Df and vasc are less common, comprising 115 and 142 images respectively. This distribution offers a diverse range of skin lesions, enhancing the dataset’s utility for training and assessing machine learning models designed for the classification and detection of skin cancer. Figure 2 displays various classes of the HAM10000 dataset.

To enhance the validation of our model, we further leverage DermaMNIST from the MedMNISTv215 dataset, comprising 10,015 dermatoscopic images categorized into seven distinct diseases, forming a multi-class classification challenge. The images are divided into training, validation and test sets at the ratio of 7:1:2. The original images, sized at 3 × 600 × 450 are reduced to 3 × 28 × 28 for processing. Figure 3 displays various classes of the DermaMNIST dataset.

Methodology and implementation

Data balancing and pre-processing

To prepare the input data for analysis, data preprocessing is vital. It makes the data suitable for the deep learning models to draw meaningful insights and predictions from the data, enhancing the model performance while ensuring data quality.

In this study, the HAM1000014 dataset is employed. As the original HAM10000 is highly imbalanced (referring to the Figure 4(a)), the data is balanced by using the technique of trimming and augmentation. The original dataset comprises 10,015 images. The trimming operation ensures that no more than 6000 images can belong to a single class. Then image augmentation techniques consisting of horizontal flip, rotation, random brightness contrast, random gamma, random crop are performed in the case of the classes having less than 6000 samples. After balancing, the size of the dataset increases to 42,000, where each class has 6000 samples. After balancing the data, the dataset is split into train, test and validation set. The initial size of the images in HAM10000 dataset is 3 × 28 × 28. To enhance the performance of the ensemble model that we have employed, the images are resized to the size of 3 × 96 × 96. The increase in spatial resolution enables the model to distinguish intricate details, which is important for distinguishing the skin cancer lesions. These preprocessing steps have enabled our ensemble model to capture intricate features while improving feature extraction which is essential for highly accurate classifications of biomedical images. Figure 4(a) and Figure 4(b) represent the number of samples of each class of the HAM10000 dataset before and after data balancing respectively. Figure 5 displays original and augmented images of various classes from the HAM10000 dataset.

Proposed model architecture

Xception model

The Xception model created by François et al.11 at Google Inc., presents itself as a major innovation in the landscape of CNN42 design through the method of depth-wise separable convolutions that reimagine Inception modules in CNNs. Depth-wise separable convolutions can be viewed as a simple intermediate structure between the extreme cases of standard convolutional layers, such as this way. The Xception model was studied on a large image type dataset that contains about 350 million images of 17,000 separate classes, see details of training and performance. The architecture prototypes (illustrated in the Fig. 6) contained 36 layers of CNN in this model, laid out in space composed of 14 units, all but one with linear residuals connecting residual connections on the entry as well as the last units, for which the depth-wise separable process is overturned. Overall, the Xception architecture exhibited modest improvements in classification performance on the ImageNet dataset43 and substantial enhancements on the JFT dataset44 compared to architectures such as InceptionV3 and ResNet-152. Figure 6 gives the architectural flow of the Xception model.

In our study, to increase the efficiency we have introduced a few customisations in the Xception based CNN model. During model building, the model input is passed through the Xception backbone, then passed through a Global Average pooling layer to decrease spatial dimensions. The final dense layer with Softmax activation outputs class probabilities for skin cancer classes.

InceptionResNetV2 model

InceptionResNetV212 is a renowned CNN devised by Google Researchers to excel in image classification tasks. It blends the concepts of Inception and ResNet to create a powerful deep learning model for image classification tasks. This architecture starts with a stem network that is responsible for initial feature extraction from the input image. Following this, a series of Inception modules are stacked together. These modules employ parallel convolutional branches of various filter sizes, enabling the capturing of features across multiple scales. Inspired by ResNet, InceptionResNetV212 integrates residual connections throughout the architecture. These connections allow gradients to flow more easily during training. This smoother flow defeats the vanishing gradient problem, ultimately leading to faster and more effective training convergence. To boost the network’s ability to learn complex features, InceptionResNetV2 strategically inserts special “reduction blocks” between the Inception modules. These blocks act like data compressors, summarizing the information and allowing the network to focus on capturing higher-level concepts from the image. At the end, the network employs a technique called “global average pooling” to transform the remaining spatial information into a single, streamlined vector. This vector is then fed into a softmax output layer for classification. In Figure 7, we get an overview of the architecture of the InceptionResNetV2 model.

In our study, to increase the efficiency we have introduced a few customisations in the InceptionResNetV2 based CNN model. During model building, the model input is passed through the InceptionResNetV2 backbone, then further passed through a Global Average pooling layer to decrease spatial dimensions. The final dense layer with Softmax activation outputs class probabilities for skin cancer classes.

MobileNetV2 model

MobileNetV213 is a lightweight CNN architecture that is designed precisely for mobile and embedded vision applications. It was developed as an improvement over its predecessor, MobileNetV1, with a focus on achieving better efficiency in terms of both computational resources and model size. The core of MobileNetV2’s architecture lies in its inverted residual structure. This differs from traditional residual blocks where the input and output have similar dimensions. In MobileNetV2, the residual connections are placed between bottleneck layers, which are significantly thinner than the feature maps they process. This strategy enables streamlined processing while retaining the advantages of residual learning. In its inverted residual blocks, MobileNetV2 utilizes depth-wise separable convolutions. These convolutions involve applying a single filter per input channel, which is computationally efficient. Following the depth-wise layer, point-wise convolutions merge the outcomes, adding non-linearity. This fusion strikes a favourable equilibrium between feature extraction and model size. To complement its architectural design, MobileNetV2 also incorporates various optimization techniques such as batch normalization and the ReLU6 activation function. These techniques help accelerate convergence during training while ensuring stable and efficient inference on mobile and embedded devices. In Figure 8, we get an overview of the architecture of MobileNetV2 model.

In our study, to increase the efficiency we have introduced a few customisations in the MobileNetV2 based CNN model. During model building, the model input is passed through the MobileNetV2 backbone, then further passed through a Global Average pooling layer that is employed to decrease spatial dimensions. Two dense layers with ReLU activation are incorporated, each followed by a dropout layer with a 0.4 dropout rate to mitigate overfitting. The final dense layer with softmax activation outputs class probabilities for skin cancer classes.

Proposed fuzzy ensemble model

Our motivation to utilise the technique of fuzzy ensemble to enhance the accuracy is derived from a number of prior studies45,46,47,48,49,50. A fuzzy ensemble is a technique that combines multiple models or classifiers using fuzzy-logic principle. This approach is used to improve predictive performance and decision making by aggregating the outputs of individual models in a flexible and adaptive manner.

The technique employed by us, which has been influenced by a prior study46, leverages rank-based fusion to enhance the predictive power of the three classifiers used. The technique involves two important steps. One of the steps is about generating the ranks of the output generated by each of the Xception11, InceptionResNetV212 and MobileNetV213 models, while the other step is about the fusion process which involves combining the ranks. In the rank generation step, the ranks are derived using mathematical formulas involving exponential decay and hyperbolic tangent. In the step involving the fusion process, the ranks of the classifiers are combined using a weighted average approach, considering both the rank values and the average scores from the classifiers. The fused scores are used to predict the class for each sample. The accuracy of the ensemble is calculated by comparing the predicted classes with the actual labels. Overall, this fuzzy rank-based ensemble technique incorporates both the rank information and the average scores from the classifiers in the fusion process, allowing the ensemble to make more accurate and precise predictions compared to the individual classifiers.

The following algorithm 1 explains the basic nature of the proposed Fuzzy Rank-based Ensemble Algorithm. The ensemble model combines predictions of three independent models to map skin lesion images to its predicted class/label. Now, the Algorithm 1 utilises 2 additional rank-based algorithms such as Algorithm 2 and Algorithm 3; which are used to initialise arrays for rank values and scores for each model’s prediction, both of these ranks are combined to create a fused rank score, following which a fusion method is applied to determine the final class prediction. Finally, the similarity between the true labels and predicted labels are calculated to derive the classification accuracy.

Proposed rank based ensemble method

In this segment, we’ll examine the mathematical structure of the proposed ensemble technique that is based on the prior study46. Let’s consider the confidence scores associated with a set of n classes, which could be denoted by \(\:(C_1^i,C_2^i,C_3^i, \dots C_n^i)\) here i = 1, 2, 3. Now, we perform summation of all confidence scores procured by the base learners, shown in the Eq. 1

Now, we generate fuzzy ranks of each of the classes using 2 non-linear functions, hyperbolic tangent and exponential function. We denote these fuzzy ranks as \(\:\left\{{X}_{1}^{{i}_{1}},\:{X}_{2}^{{i}_{1}},\:{X}_{3}^{{i}_{1}},\:\dots\:,\:{X}_{n}^{{i}_{1}}\right\}\) and \(\:\left\{{X}_{1}^{{i}_{2}},\:{X}_{2}^{{i}_{2}},\:{X}_{3}^{{i}_{2}},\:\dots\:,\:{X}_{n}^{{i}_{2}}\right\}\) generated by the two nonlinear functions.

We define the domain of the fuzzy rank functions as [0,1] since \(\:{C}_{k}^{{i}_{1}}\:\in\:\left[\text{0,1}\right]\).

Equation (2) establishes a reward system for classification, where approaching x towards 1 results in an increased reward. Conversely, Eq. (3) quantifies the deviation from 1.

Let \(\:\left({Y}_{1}^{i},\:{Y}_{2}^{i},\:{Y}_{3}^{i},\:\dots\:,\:{Y}_{n}^{i}\right)\) denote the fused rank scores, where \(\:{Y}_{k}^{i}\) is given by Eq. (4)

The current rank scores are derived by combining their individual rewards and deviations, based on a specific confidence score achieved by a base learner. This fused rank score is quite similar to the concept proposed by Kundu et al.45, while their fuzzy based ensemble scores were used using Gompertz function.

Rank score is determined by multiplying the reward and deviation of the certain confidence score in a base learner. Given that the range of Eq. (3) is smaller than that of Eq. (2), Eq. (3) will primarily influence the product. A small deviation derived from the confidence score lessens the rank score. The rank scores are finally needed to compute the fused scores.

This indicates the confidence level in a particular class, resulting from the multiplication of fuzzy ranks produced by two distinct functions. The fused score tuple \(\:\left({Z}_{1},\:{Z}_{2},\:{Z}_{3},\:\dots\:,\:{Z}_{n}\right)\), denoted as \(\:{Z}_{k}\), is defined by Eq. (5).

The combined score can serve as the ultimate score for each class. We identify the class with the lowest combined score, considering it the winner according to Eq. (6). The computational complexity of this fusion approach is \(\:O\left(number\:of\:classes\right).\)

Fine-tuning

In case of all the base models, we used models pre-trained on the Imagenet dataset while customising it. The input images are of size 3 × 96 × 96 and the batch size is 32. Adam optimizer is used because of its efficiency optimization and adaptive learning, while Sparse categorical cross entropy is selected as the loss function. The ReduceLROnPlateau function will monitor the validation loss during training. If the validation loss does not improve for 5 consecutive epochs, the learning rate will be reduced by a factor of 0.1. EarlyStopping with these parameters will monitor the validation loss during training. If the validation loss does not improve for 20 consecutive epochs, training will be stopped early and the model’s weights will be restored to those from the epoch with the best validation loss. Table 1 shows the list of all common fine-tuning parameters as well as their values set for the three candidate deep CNN models. It is to be noted that for the Xception model and the InceptionResNetV2 model, the epoch is set to be 30. For the MobileNetV2 model, the epoch is set to be 50.

Results analysis

Analysis on HAM10000 dataset

It is to be noted that all experimental protocols were approved by Department of Information Technology, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India. To examine the effectiveness of our fuzzy-ensemble model against the augmented and balanced HAM10000 dataset, we used several key metrics. These include Accuracy, Precision, F1-score, Recall16. These metrics are used to examine the model’s capability to precisely categorize skin cancer lesions across different classes. Additionally, the results are visualised with the help of a confusion matrix, train-validation loss graph and train-validation accuracy graph to gain a deeper understanding of the model’s strength and areas of improvement. The accuracies achieved individually by the Xception11 model, InceptionResNetV212 and MobileNetV213 against the dataset are 94.79%, 79.17% and 94.30% respectively. The accuracy achieved by the fuzzy ensemble of these individual models is 95.14%.

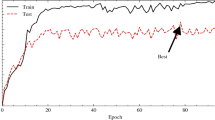

Figures 9, 10 and 11 portrays the loss curve and the accuracy curve achieved by the individual Xception, InceptionResNetV2 and MobileNetV2 based models on the balanced HAM10000 dataset. It can be noted from both the accuracy and loss curves that around epoch = 20, the performance of the Xception and MobileNetV2 model saturates.

Figure 12 represents the ROC Curve for Xception, InceptionResNetV2, MobileNetV2 model on HAM10000 dataset. Classes like ‘df’ and ‘vasc’ have a high AUC in case of all the three base models. High AUC for a class indicates strong model performance and good discrimination ability for that class. A high AUC value (close to 1) for a particular class indicates that the model can effectively distinguish between instances of that class and instances of other classes. In the case of the Xception model, the AUC of each of the classes lies in the range of 0.99 to a value closer to 1.00. In the case of the InceptionResNetV2 model, the AUC of each of the classes lies in the range of 0.93 to a value closer to 1.00. In the case of the MobileNetV2 model, the AUC of each of the classes lies in the range of 0.99 to a value closer to 1.00.

Table 2 portrays the comparison of the accuracies attained by the individual Xception model, InceptionResNetV2 model, MobileNetV2 model and the fuzzy ensemble of these models on the augmented and balanced HAM10000 dataset. It can be noted that the accuracy achieved by the fuzzy ensemble of all the three models exceeds the performance of the individual models. Figure 13 shows the final classification report generated by the fuzzy ensemble of all the three models for the balanced HAM10000 dataset.

Figure 14 shows the confusion matrix generated by the fuzzy ensemble model of the Xception, InceptionResNetV2 and MobileNetV2 models on the augmented and balanced HAM10000 dataset. Out of all 1276 ‘akiec’ images, the model correctly predicted 1242 images as ‘akiec’, while it miscategorised 9 ‘akiec’ images as ‘bcc’, 13 ‘akiec’ images as ‘bkl’, 12 ‘akiec’ image as ‘nv’ and 0 ‘akiec’ images as images of any other class. Out of all 1174 ‘bcc’ images, the model correctly predicted 1159 images as ‘bcc’, while it miscategorised 6 ‘bcc’ images as ‘akiec’, 4 ‘bcc’ images as ‘bkl’, 2 ‘bcc’ images as ‘mel’, 3 ‘bcc’ images as ‘nv’ and 0 ‘bcc’ images as images of any other class. Out of all 1182 ‘bkl’ images, the model correctly predicted 1093 images as ‘bkl’, while it miscategorised 15 ‘bkl images as ‘akiec’, 8 ‘bkl’ images as ‘bcc’, 2 ‘bkl’ images as ‘df’, 24 ‘bkl’ images as ‘mel’, 39 ‘bkl’ images as ‘nv’ and 1 ‘bkl’ image as ‘vasc’. Out of 1173 ‘df’ images, 1172 ‘df’ images were correctly predicted by the model while 1 ‘df’ image was miscategorised as ‘bcc’. Out of all 1172 ‘mel’ images, 1009 images were correctly predicted as ‘mel’, while 1 ‘mel’ image miscategorised as ‘akiec’, 13 ‘mel’ images were miscategorised as ‘bcc’, 52 ‘mel’ images were miscategorised as ‘bkl’, 4 ‘mel’ images were miscategorised as ‘df’, 90 ‘mel’ images were miscategorised as ‘nv’ and 3 ‘mel’ images were miscategorised as ‘vasc’. Out of all 1226 ‘nv’ images, 1120 images were correctly predicted, while 16 ‘nv’image was miscategorised as ‘akiec’, 7 ‘nv’ images were miscategorised as ‘bcc’, 36 ‘nv’ images were miscategorised as ‘bkl’, 2 ‘nv’ images were miscategorised as ‘df’, 41 ‘nv’ images were miscategorised as ‘mel’ and 4 ‘nv’ images were miscategorised as ‘vasc’. All 1197 ‘vasc’ images were correctly predicted.

Additional testing on DermaMNIST dataset

To further assess the performance of our fuzzy-ensemble model against other datasets containing skin-cancer lesions, we tested the effectiveness of the ensemble model against the DermaMNIST dataset of the MedMNISTv2 collection. The key metrics used to determine the efficiency of the performance of the model on this dataset include accuracy, precision, f1 score, recall, support. Additionally, the results are visualised with the help of a confusion matrix, train-validation loss graph and train-validation accuracy graph to gain a deeper understanding of the model’s strength and areas of improvement. The accuracies achieved individually by the Xception model, InceptionResNetV2 and MobileNetV2 against the dataset are 75.81%, 75.66% and 73.32% respectively. The accuracy achieved by the fuzzy ensemble of these individual models is 78.25%, which transcends the benchmark accuracy of 76.8% proving the efficiency of the model.

Figures 15, 16 and 17 portrays the loss curve and the accuracy curve achieved by the individual Xception, InceptionResNetV2 and MobilenetV2 based models on the DermaMNIST dataset. It can be noted that from the curves that around epoch = 15, the performance of the Xception model saturates while in the case of the InceptionResNetv2 and the MobileNetV2 model, the performances of the models saturate at around epoch = 20. There exists a slight problem of overfitting in case of all the models.

Figure 18 represents the ROC Curve for Xception, InceptionResNetV2, MobileNetV2 model on the DermaMNIST dataset. In the case of the Xception model, the AUC of each of the classes lies in the range of 0.85 to 0.95. In the case of the InceptionResNetV2 model, the AUC of each of the classes lies in the range of 0.87 to 0.96. In the case of the MobileNetV2 model, the AUC of each of the classes lies in the range of 0.86 to 0.95.

Table 3 portrays the comparison of the accuracies attained by the individual Xception model, InceptionResNetV2 model, MobileNetV2 model and the fuzzy ensemble of these models on DermaMNIST dataset. It can be noted that the accuracy achieved by the fuzzy ensemble of all the three models exceeds the performance of the individual models and also exceeds the benchmark accuracy for the DermaMNIST dataset. Figure 19 shows the final classification report generated by the fuzzy ensemble of all the three models for DermaMNIST dataset.

Figure 20 shows the confusion matrix generated by the fuzzy ensemble model of the Xception, InceptionResNetV2 and MobileNetV2 models on the DermaMNIST dataset. Out of all 66 ‘akiec’ images, the model correctly predicted 39 images as ‘akiec’, while it miscategorised 10 ‘akiec’ images as ‘bcc’, 8 ‘akiec’ images as ‘bkl’, 0 ‘akiec’ images as ‘df’, 2 ‘akiec’ images as ‘mel’, 7 ‘akiec’ images as ‘nv’ and 0 ‘akiec’ images as ‘vasc’. Out of all 103 ‘bcc’ images, the model correctly predicted 54 images as ‘bcc’, while it miscategorised 19 ‘bcc’ images as ‘akiec’, 8 ‘bcc’ images as ‘bkl’, 0 ‘bcc’ images as ‘df’, 2 ‘bcc’ images as ‘mel’, 17 ‘bcc’ image as ‘nv’ and 3 ‘bcc’ images as ‘vasc’. Out of all 220 ‘bkl’ images, the model correctly predicted 104 images as ‘bkl’, while it miscategorised 22 ‘bkl’ images as ‘akiec’, 7 ‘bkl’ images as ‘bcc’, 0 ‘bkl’ images as ‘df’, 12 ‘bkl’ images as ‘mel’, 75 ‘bkl’ images as ‘nv’ and 0 ‘bkl’ images as ‘vasc’. Out of all 23 ‘df’ images, the model correctly predicted 3 images as ‘df’, while it miscategorised 6 ‘df’ images as ‘akiec’, 5 ‘df’ images as ‘bcc’, 9 ‘df’ images as ‘nv’ and 0 ‘df’ images as images of any other class among the rest. Out of all 223 ‘mel’ images, 81 images were correctly predicted as ‘mel’, while 10 ‘mel’ images were miscategorised as ‘akiec’, 4 ‘mel’ image was miscategorised as ‘bcc’, 32 ‘mel’ images were miscategorised as ‘bkl’, 0 ‘mel’ image was miscategorised as ‘df’, 95 ‘mel’ images were miscategorised as ‘nv’ and 1 ‘mel’ image was miscategorised as ‘vasc’. Out of all 1341 ‘nv’ images, 1266 images were correctly predicted, while 14 ‘nv’ images were miscategorised as ‘akiec’, 6 ‘nv’ images were miscategorised as ‘bcc’, 31 ‘nv’ images were miscategorised as ‘bkl’, 0 ‘nv’ image was miscategorised as ‘df’, 23 ‘nv’ images were miscategorised as ‘mel’ and 1 ‘nv’ image was miscategorised as ‘vasc’. Out of all 29 ‘vasc’ images, 22 images were correctly predicted, while 1 ‘vasc’ image was miscategorised as ‘bcc’, 6 ‘vasc’ images were miscategorised as ‘nv’ and 0 ‘vasc’ images were miscategorised as images of any other class among the rest.

Grad-CAM analysis

For interpreting and visualising the regions of the input images that influence the decision-making of the individual models (Xception, InceptionResnetv2, MobileNetV2) we used the technique of Grad-CAM51. In our research, the Grad-CAM visualisations, used in case of both the balanced Ham-10,000 dataset and the DermaMNIST dataset have illuminated the model’s focus on significant features that are important for skin-cancer detection.

The process of generating the heatmap includes computing the gradients of the loss with respect to the convolutional outputs, calculating guided gradients by applying ReLU to both the convolutional outputs and the gradients, computing the weights by averaging the guided gradients. The class activation map is then generated by summing the weighted convolutional outputs. The heatmap generated is then normalised and resized. The heatmap is superimposed on the original image with a blending factor of 0.8. The superimposed image is converted to RGB format.

Figures 21, 22 and 23 display the original images against their respective Grad-CAM visualisations for different layers in each individual model (block1_conv1 layer for Xception model, conv2d_4 layer for InceptionResNetV2 model and Conv1 for MobileNetV2 model) for the balanced HAM10000 dataset.

Figures 24, 25 and 26 display the original images against their respective Grad-CAM visualisations for different layers in each individual model (block1_conv1 layer for Xception model, conv2d_12 layer for InceptionResNetV2 model and Conv1 for MobileNetV2 model) for the DermaMNIST dataset from the MedMNISTv2 collection.

Comparison with existing research

To further analyse the efficiency of our ensemble model, we compared the results attained by the fuzzy-ensemble model with that of other existing works in case of both the HAM10000 dataset and the DermaMNIST dataset. In case of the DermaMNIST dataset, the accuracy attained by the fuzzy-ensemble model (78.25%) surpasses the benchmark accuracy of 76.8% attained by the Google AutoML Vision model. Table 4 displays the comparison of the accuracies achieved by our approach compared to other works involving the HAM10000 dataset for skin cancer classification. Table 5 displays the comparison of the accuracy achieved by our fuzzy ensemble model of Xception11, InceptionResnetV212 and MobileNetV213 against the accuracies achieved by the other models, which are available on the MedMNISTv215 documentation. In case of the HAM10000 dataset, the performance of our model is acceptable compared to other works on HAM10000 datasets involving CNN models.

Conclusion & future works

This research has successfully demonstrated the effectiveness of the fuzzy ensemble model to classify skin cancer images. By integrating fuzzy logic with ensemble learning techniques, we have achieved notable improvements in classification accuracy compared to individual classifiers or traditional ensemble methods. In our study, we employed various models to classify skin cancer images each yielding distinct accuracies. The Xception11 model achieved a classification accuracy of 94.79%, InceptionResNetV212 model reached 79.17% and MobileNetV213 model attained an accuracy of 94.30% on 96 × 96 images. Leveraging the complementary strengths of multiple classifiers within a fuzzy framework, our approach has provided robustness against uncertainties and variations present in skin cancer images and achieved an impressive accuracy of 95.14%. The result is acceptable compared to other works in the domain of classification of skin cancer images involving the HAM10000 dataset.

In the domain of skin cancer image classification, the study points towards several promising avenues for future exploration. In upcoming years, harnessing advanced GPU technology could accommodate larger batch sizes to fully utilize the available computational resources efficiently which can lead to faster training times and potentially better convergence of the model during training. Due to computational limitations, there exists some limitations in our model as the images could not be preprocessed and resized at higher resolutions. Also due to the usage of 3 base models in the ensemble, the model can become less scalable with increasing input features, leading to increased computational and memory requirements. However, our preliminary results suggest a noteworthy enhancement in the model’s performance with increased resolution. As a result, forthcoming studies should concentrate on exploring the proposed approach with high-resolution pre-processed images, thereby unlocking the model’s full potential in situations where intricate spatial details are crucial.

Data availability

No datasets are generated during the current study. The datasets analyzed during this work can be found at: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/kmader/skin-cancer-mnist-ham10000 and https://medmnist.com/.

References

Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). Skin cancer. Retrieved May 27. from (2024). https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/15818-skin-cancer

Godbole, V. K., Toprani, H. T. & Shah, H. H. Skin cancer in saurashtra. Ind. J. Pathol. Bacteriol. 11, 183–189 (1968).

Alam, T. M. et al. An efficient deep learning-based skin Cancer classifier for an Imbalanced dataset. Diagnostics 12 (9), 2115. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12092115 (2022).

Manu Goyal, T., Knackstedt, S. & Hassanpour, Y. S. Artificial intelligence-based image classification methods for diagnosis of skin cancer: challenges and opportunities, computers in Biology and Medicine, 127, 2020, 104065, ISSN 0010-4825, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.104065

Lallas, A., Longo, C., Manfredini, M., Benati, E., Babino, G., Chinazzo, C., … Moscarella,E. (2018). Accuracy of dermoscopic criteria for the diagnosis of melanoma in situ.JAMA dermatology, 154(4), 414–419.

Scope, A., Dusza, S. W., Marghoob, A. A. & Halpern, A. C. Dermoscopy vs. reflectance confocal microscopy for the diagnosis of lentigo maligna. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 31 (8), 1312–1319 (2017).

Tavakolpour, S., Daneshpazhooh, M. & Mahmoudi, H. Skin cancer: Genetics, immunology, treatments, and psychological care. In Cancer Genetics and Psychotherapy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, ; 851–934. (2017).

Chan, S. et al. Machine learning in dermatology: current applications, opportunities, and limitations. Dermatol. Ther. 10, 365–386 (2020).

Liao, H., Li, Y. & Luo, J. Skin disease classification versus skin lesion characterization: Achieving robust diagnosis using multi-label deep neural networks. Proceedings - International Conference on Pattern Recognition, pp. 355–360. (2017).

Aburaed, N., Panthakkan, A., Al-Saad, M., Amin, S. A. & Mansoor, W. Deep Convolutional Neural Network (DCNN) for Skin Cancer Classification, 2020 27th IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Circuits and Systems (ICECS), Glasgow, UK, 2020, pp. 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICECS49266.2020.9294814

Chollet, F. Xception: Deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 1251–1258). (2017).

InceptionResNetV2. Szegedy, Christian, Sergey Ioffe, Vincent Vanhoucke, and Alexander Alemi. Inception-v4, inception-resnet and the impact of residual connections on learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, vol. 31, no. 1. (2017).

Sandler, M., Howard, A., Zhu, M., Zhmoginov, A. & Liang-Chieh Chen Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 4510–4520. (2018).

Tschandl, P., Rosendahl, C. & Kittler, H. The HAM10000 dataset, a large collection of multi-source dermatoscopic images of common pigmented skin lesions. Sci. Data. 5, 180161. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2018.161 (2018).

Yang, J. et al. MedMNIST v2 - a large-scale lightweight benchmark for 2D and 3D biomedical image classification. Sci. Data. 10, 41. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01721-8 (2023).

Yacouby, R. & Axman, D. Probabilistic extension of precision, recall, and F1 score for more thorough evaluation of classification models. 79–91. (2020). https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2020.eval4nlp-1.9

Bradley, A. P. The use of the area under the ROC curve in the evaluation of machine learning algorithms. Pattern Recogn. 30 (7), 1145–1159. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-3203(96)00142-2 (1997).

Anand, V. et al. Deep learning based automated diagnosis of skin diseases using dermoscopy. Computers Mater. Continua. 71 (2), 3145–3160. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2022.022788 (2022).

Mehak Arshad, M. A. et al. A Computer-Aided Diagnosis System Using Deep Learning for Multiclass Skin Lesion Classification, Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, vol. Article ID 9619079, 15 pages, 2021. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9619079

Agyenta, C. & Mathias Akanzawon Skin lesion classification based on convolutional neural network. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. Trends. 3 (01), 21–26. https://doi.org/10.38094/jastt301121 (2022).

Datta, S. K., Shaikh, M. A., Srihari, S. N. & Gao, M. in Soft Attention Improves Skin Cancer Classification Performance. Lecture Notes in Computer Science()Vol. 12929 (eds Reyes, M.) (Springer, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-87444-5_2Interpretability of Machine Intelligence in Medical Image Computing, and Topological Data Analysis and Its Applications for Medical Data. IMIMIC TDA4MedicalData 2021 2021.

Naeem, A. & Anees, T. DVFNet: a deep feature fusion-based model for the multiclassification of skin cancer utilizing dermoscopy images. PLoS ONE. 19 (3), e0297667. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297667 (2024).

Hameed, M., Zameer, A. & Muhammad Asif Zahoor Raja. and. A comprehensive systematic review: advancements in skin Cancer classification and segmentation using the ISIC dataset. CMES-Computer Model. Eng. Sci. 140.3 (2024).

Gayatri, E. & Aarthy, S. L. ‘Reduction of overfitting on the highly imbalanced ISIC-2019 skin dataset using Deep Learning Frameworks’. 1 Jan : 53–68 (2024).

Velaga, N., Vardineni, V. R., Tupakula, P., Pamidimukkala, J. S. & Communications Skin Cancer Detection Using the HAM10000 Dataset: A Comparative Study of Machine Learning Models, 2023 Global Conference on Information Technologies and (GCITC), Bangalore, India, pp. 1–7, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/GCITC60406.2023.10425889

Yang, D. et al. Skin lesion classification based on hybrid self-supervised pretext task. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 34 (2), e23058. https://doi.org/10.1002/ima.23058 (2024).

Khan, M. A., Sharif, M., Akram, T., Damaševičius, R. & Maskeliūnas, R. Skin lesion segmentation and multiclass classification using deep learning features and Improved Moth Flame optimization. Diagnostics 11 (5), 811. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11050811 (2021).

Srinivasu, P. N. et al. Classification of skin Disease using deep learning neural networks with MobileNet V2 and LSTM. Sensors 21 (2852). https://doi.org/10.3390/s21082852 (2021).

Nguyen, V. D., Bui, N. D. & Do, H. K. Skin lesion classification on Imbalanced Data using deep learning with soft attention. Sensors 22, 7530. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22197530 (2022).

Ali, K. et al. Multiclass skin cancer classification using EfficientNets–a first step towards preventing skin cancer. Neurosci. Inf. 2, 100034 (2022).

Şengül, S. B. & İlker, A. Ö. MResCaps: enhancing capsule networks with parallel lanes and residual blocks for high-performance medical image classification. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 34 (4), e23108 (2024).

Khalid, M., Hosny, W., Said, M., Elmezain, M. A. & Kassem Explainable deep inherent learning for multi-classes skin lesion classification. Appl. Soft Comput. 159, 1568–4946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111624 (2024).

Alsahafi, Y. S., Kassem, M. A. & Hosny, K. M. Skin-Net: a novel deep residual network for skin lesions classification using multilevel feature extraction and cross-channel correlation with detection of outlier. J. Big Data. 10, 105. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-023-00769-6 (2023).

Soaad, M. et al. Automated system for classifying uni-bicompartmental knee osteoarthritis by using redefined residual learning with convolutional neural network, Heliyon, 10, Issue 10, 2024, e31017, ISSN 2405–8440, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e31017

Mohamed, A. et al. and. Explainable Transfer Learning-Based Deep Learning Model for Pelvis Fracture Detection. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2023 (2023). (2023). https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/3281998

Halder, A. et al. Implementing vision transformer for classifying 2D biomedical images. Sci. Rep. 14, 12567. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63094-9 (2024).

Naeem, A., Farooq, M. S., Khelifi, A. & Abid, A. Malignant melanoma classification using deep learning: datasets, performance measurements, challenges and opportunities. IEEE Access. 8, 110575–110597 (2020).

Riaz, S., Naeem, A., Malik, H., Naqvi, R. A. & Loh, W. K. Federated and transfer learning methods for the classification of Melanoma and Nonmelanoma skin cancers: a prospective study. Sens. (Basel). 23 (20), 8457. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23208457 (2023). PMID: 37896548; PMCID: PMC10611214.

Naeem, A. et al. SNC_Net: skin Cancer detection by integrating handcrafted and deep learning-based features using Dermoscopy images. Mathematics 12 (7), 1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/math12071030 (2024).

Ahmad Naeem, A. H. & Khan Salah u din Ayubi, and Hassaan Malik, Predicting the Metastasis Ability of Prostate Cancer using Machine Learning Classifiers, JCBI, vol. 4, no. 02, pp. 1–7, Mar. (2023).

Hamna Ayesha, A., Naeem, A. H., Khan, K., Abid & Aslam, N. Multi-classification of Skin Cancer Using Multi-model Fusion Technique, JCBI, vol. 5, no. 02, pp. 195–219, Sep. (2023).

Sultana, F., Sufian, A. & Dutta, P. Advancements in Image Classification using Convolutional Neural Network, Fourth International Conference on Research in Computational Intelligence and Communication Networks (ICRCICN), Kolkata, India, 2018, pp. 122–129, (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRCICN.2018.8718718

Deng, J. et al. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database, 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Miami, FL, USA, pp. 248–255, (2009). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2009.5206848

JFT-300 M Dataset. https://paperswithcode.com/dataset/jft-300m

Rohit Kundu, H., Basak, P. K., Singh, A. & Ahmadian Massimiliano Ferrara, Ram Sarkar: Fuzzy rank–based fusion of CNN models using Gompertz function for screening COVID–19 CT–scans, In: Scientific Reports, 11:14133, pp. 1–12, (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93658-y)

Manna, A. et al. A fuzzy rank-based ensemble of CNN models for classification of cervical cytology. Sci. Rep. 11, 14538. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93783-8 (2021).

Sahoo, K. K. et al. MIC_FuzzyNET: fuzzy integral based ensemble for automatic classification of Musical instruments from Audio signals. IEEE Access. 10, 100797–100811 (2022).

Rohit Kundu, P. K., Singh, S., Mirjalili, R. & Sarkar COVID-19 detection from lung CT-Scans using a fuzzy integral-based CNN ensemble, In: Computers in Biology and Medicine, Elsevier, 138, 104895, (DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104895) (2021).

Sahoo, K. K., Dutta, I., Ijaz, M. F., Wozniak, M. & Singh, P. K. TLEFuzzyNet: fuzzy rank-based ensemble of transfer learning models for emotion Recognition from Human speeches. IEEE Access. 9, 166518–166530 (2021).

Trishita Dhara, P. K., Singh, M. & Mahmud A fuzzy ensemble-based deep learning model for emotion recognition from EEG signals, In: Cognitive Computation, Springer, 1–15, (2023).

Selvaraju, R. R. et al. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, pp. 618–626. (2017).

Huang, H. W., Hsu, B. W. Y., Lee, C. H. & Tseng, V. S. Development of a light-weight deep learning model for cloud applications and remote diagnosis of skin cancers. J. Dermatol. 48, 310–316 (2021).

Khan, M. A., Zhang, Y. D., Sharif, M. & Akram, T. Pixels to classes: Intelligent learning framework for multiclass skin lesion localization and classification. Comput. Electr. Eng. 90, 106956 (2021).

Camilo Calderón, K., Sanchez, S., Castillo, H. & Arguello, B. I. L. S. K. A bilinear convolutional neural network approach for skin lesion classification, Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine Update, 1, 2021, 100036, ISSN 2666–9900, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpbup.2021.100036

Hoang, L., Lee, S. H., Lee, E. J. & Kwon, K. R. Multiclass skin lesion classification using a Novel Lightweight Deep Learning Framework for Smart Healthcare. Appl. Sci. 12, 2677 (2022).

Popescu, D., El-khatib, M. & Ichim, L. Skin lesion classification using collective intelligence of multiple neural networks. Sensors 22 (12), 4399. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22124399 (2022).

Yang, G., Luo, S. & Greer, P. A. Novel vision transformer model for skin Cancer classification. Neural Process. Lett. 55, 9335–9351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11063-023-11204-5 (2023).

Gairola, A. K. et al. Multi-feature Fusion Deep Network for skin disease diagnosis. Multimed Tools Appl. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-024-18958-7 (2024).

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to acknowledge contribution to this research from the Rector of the Silesian University of Technology underproquality grant 09/020/RGJ25/0041.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H., A.D., S.G., M.W.,; methodology, M.W. M.F.I.; software, A.H., A.D., S.G., M.W, M.F.I., P.K.S.,.; validation, A.H., A.D., S.G., M.W.,M.W., M.F.I., ., P.K.S., .; formal analysis, A.H., A.D., S.G., P.K.S., .,; investigation, M.W., M.F.I.; resources, A.H., A.D., S.G.,P.K.S., data curation, A.H., A.D., S.G.,P.K.S., writing—original draft preparation, A.H., A.D., S.G.,P.K.S., ; writing—review and editing, , M.W ., M.F.I.; visualization, A.H., A.D., S.G.,., supervision M.W., and M.F.I., P.K.S ; project administration, P.K.S.,; M.W.,; and M.F.I ; funding acquisition, M.W., M.F.I.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Experiment

All experiments and methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All experimental protocols were approved by Department of Information Technology, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Halder, A., Dalal, A., Gharami, S. et al. A fuzzy rank-based deep ensemble methodology for multi-class skin cancer classification. Sci Rep 15, 6268 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90423-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90423-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

AI-assisted SERS imaging method for label-free and rapid discrimination of clinical lymphoma

Journal of Nanobiotechnology (2025)

-

An optimal graph convolutional vision neural network with explainable feature optimization for improved skin cancer detection

BMC Medical Imaging (2025)

-

Beyond Accuracy: A MultiDimensional Framework for Evaluating Medical Image Classification Through Win vs. Lose Model Comparisons

Journal of Imaging Informatics in Medicine (2025)