Abstract

The three highly invasive Reynoutria species – R. japonica Houtt., Reynoutria sachalinensis (F.Schmidt) Nakai, and a hybrid of them – R. x bohemica J. Chrtek & A. Chrtková are rich sources of biologically active compounds. However, only R. japonica is accepted as an herbal drug source in the pharmacopeias as Polygoni cuspidati rhizoma et radix, while R. sachalinensis is used in folk phytotherapy. The hybrid species can be misidentified as R. japonica due to its morphological resemblance. This study intended to explore genetic identity, diversity, and population structure using sequence-related amplified polymorphisms (SRAP) and start codon targeted (SCoT) markers correlated with morphological characteristics and metabolic profiles in fifteen accessions of Reynoutria species from invasive populations in Central Europe (Wroclaw, south-west Poland). The results suggest that morphological identification based on leaf morphology is clear for R. sachalinensis but fails to distinguish between R. japonica and R. × bohemica unambiguously. The qualitative HPLC/DAD/ESI-HR-QTOF-MS analysis determined the chemical composition of collected samples, revealing 117 compounds belonging to carbohydrates, stilbenes, flavan-3-ols, procyanidins, anthraquinones, organic acids, and naphthalenes. Out of these, the six compounds were quantitated. Based on LC-MS data for 117 compounds, the cluster analysis categorized the fifteen accessions into two distinctive clusters. All SCoT and SRAP markers showed medium (0.1 to 0.25) to high (0.30 to 0.40) levels of PIC, high levels of polymorphic bands (85 and 89%, respectively) and relatively high mean values for Rp (6.42 and 7.0) and were considered informative and differentiating. Partitioning the genetic diversity with AMOVA showed that variation within the populations was higher than among them, as seen in the combined data from SCoT and SRAP (53.04% vs. 46.96%, respectively) and the analyses of individual markers. Genetic diversity indices revealed that chosen genetic markers efficiently assess the variability within the genus Reynoutria. Na varied from 1.57 in R. sachalinensis to 3.34 in R. x bohemica, and Ne was low and almost identical for all species (~ 1.6). Nei’s diversity (H) indicated low genetic diversity (< 0.2) in all species, with the highest value for hybrid (0.184). Despite low H values, Shannon’s index (I) remains high and similar (R. japonica − 5.21, R. x bohemica – 5.28, and R. sachalinensis − 5.45). The number (NPL) and percentage of polymorphic loci (PPL) for the hybrid (160 and 52.98%) were almost twice as high as for the parent species. The populations exhibited moderate GST values (0.159) and a gene flow (Nm = 1.317). Genetic structure analysis with the Evanno test (ΔK = 2) reveals two genetic groups with the highest admixture in the hybrid population. The cluster analysis dendrograms based on LC-MS data, genetic distance, and leaf morphology categorized the fifteen accessions into three clusters, revealing unequivocal separation of the R. sachalinensis from both other taxa. According to Baker’s methodology, the highest correlation between dendrograms was observed between genetic and morphological data, with values of 0.85. Lower correlations were noted between molecular markers and phytochemical profile, as well as between morphology and phytochemical profile. The study suggests the effectiveness of combined morphological, phytochemical, and SCoT and SRAP molecular marker systems in assessing the identity of plant material. This approach can also be used in further studies on the population structure, spread, diversity, and evolution of invasive species such as Reynoutria spp.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The genus Reynoutria Houtt. (Polygonaceae) is currently represented by six accepted species (https://powo.science.kew.org/): Reynoutria ciliinervis (Nakai) Moldenke, Reynoutria compacta (Hook.f.) Nakai, Reynoutria forbesii (Hance) T.Yamaz., Reynoutria japonica Houtt., Reynoutria multiflora (Thunb.) Moldenke, Reynoutria sachalinensis (F.Schmidt) Nakai, with two hybrids: Reynoutria × bohemica Chrtek & Chrtková and Reynoutria × moravica (Hodálová & Mereďa) Olshanskyi & Antonenko. However, three species are considered noxious invasive weeds in many areas of the world, and these are - R. japonica Houtt., R. sachalinensis (F.Schmidt) Nakai, and R. x bohemica J. Chrtek & A. Chrtková, the latter being a hybrid between two former species. All three have the status of highly invasive alien species in Europe, North America, and New Zealand1,2,3.

R. japonica (synonyms: Polygonum cuspidatum Sieb. et Zucc.; Fallopia japonica (Houtt.) Ronse Decraene var. japonica; Japanese knotweed) grows naturally in Sakhalin and Kuril Islands, Japan, Korea, south-west China, Taiwan and Vietnam. It is most often found on sunny slopes of hills and mountains (up to 3800 m above sea level), in river valleys, near roads, and on the edges of forests and it is the main pioneering species inhabiting the areas covered with volcanic lava1. The natural range of R. sachalinensis (Synonyms: Fallopia sachalinensis (F. Schmidt ex Maxim.) Ronse Decraene; Polygonum sachalinense F. Schmidt; Giant knotweed) includes Sakhalin, the southern part of the Kuril Islands, Hokkaido and Honshu in Japan, and the island of Ullyng between Japan and Korea. It occurs in similar habitats as the Japanese knotweed but in lower mountain locations – up to 1050 m above sea level4. Both species were brought to Europe from Asia as ornamental plants – R. japonica in the 1820s and R. sachalinensis in the 1860s. They began to appear outside of cultivation just after a few years. Currently, they have taken over Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand, and they also occur in North Africa and Chile5,6.

R. x bohemica (synonym: Fallopia x bohemica (Chrtek & A. Chrtková) J.P. Bailey; Bohemian knotweed) was first described in Czechia in 19837 as a hybrid formed by pollination of male sterile flowers of R. japonica with the pollen of R. sachalinensis. It is believed that this hybrid could have appeared shortly after the R. sachalinensis was brought to Europe, in the second half of the 19th century8. In Asia, where R. japonica and R. sachalinensis are native species, the hybrid species was only discovered at the end of the 20th century and named R. x mizushimae Yokouchi ex T. Shimizu9. The late isolation of R x bohemica as a separate species was probably due to its misidentification as R. japonica. The reason was that the morphological features of both species were similar, within the variability range of R. japonica. Caryological studies confirmed the distinctiveness of these species2,10.

Knotweeds are enormous rhizomatous perennials that form clonal colonies. The leaves are simple, petiolate, and arranged in two rows on the stems. Size, shape, and leaf hair can serve as diagnostic features to aid in distinguishing the knotweed species2,11. Common morphological characteristics are summarized in Table 1. However, the invasive Reynoutria species display complex morphological and genetic variations, complicating their accurate identification2,12.

Rhizomes, less often herb of R. japonica, have been used in traditional Chinese and Japanese medicine as an analgesic, antipyretic, expectorant, and diuretic in the treatment of many diseases, including inflammations, infections, asthma, atherosclerosis, hypertension, and heart diseases14. The rhizome of R. japonica was included in the European Pharmacopoeia as “Polygoni cuspidati rhizoma et radix” (Ph. Eur.9)15. R. sachalinensis and R. x bohemica are not considered equivalent medicinal plants. The rhizome of R. sachalinensis was traditionally used to some extent as a herbal medicine in East Asia for the treatment of joint pain, jaundice, amenorrhea, cough, burns, scalds, injuries, boils, and wounds16, but it was not recognized as a pharmacopoeial raw material. So far, there is no data on the medical use of R. x bohemica, which has been mainly studied for its biomass production and potential as a biofuel source17. According to our previous studies, the rhizomes of these three species differ in their phytochemical profile, which may have an impact on their biological activity18. In our previous work, over 130 compounds were tentatively identified from rhizomes of these species belonging to stilbenes, carbohydrates, procyanidins, flavan-3-ols, anthraquinones, phenylpropanoid disaccharide esters, hydroxycinnamic acids, naphthalenes and lignins19.

According to the European Pharmacopoeia, the definition of Polygonum cuspidatum rhizome and root comprises: “Dried, fragmented rhizome and root, with rootlets removed, of Reynoutria japonica Houtt. (syn. Polygonum cuspidatum Sieb. et Zucc.) collected in spring or autumn. Content: – emodin (C15H10O5; Mr 270.2): minimum 1.0% (dried drug), – polydatin (C20H22O8; Mr 390.4): minimum 1.5% (dried drug)”. The determination of emodin and polydatin content according to the European Pharmacopoeia requires the use of two different HPLC methods, which is time-consuming and laborious and may be insufficient in case of misidentification of the source species, especially the hybrid (R. x bohemica). In previous studies, our research group developed and validated the HPLC-DAD-MS method, which allows the simultaneous determination of six compounds from stilbenes: polydatin and resveratrol; anthraquinones: emodin and physcion as well as sucrose hydroxycinnamic esters: vanicoside A and vanicoside B18,20. This analytical method showed significant differences in the content of these compounds between the rhizomes of three Reynoutria species (R. japonica, R. x bohemica, and R. sachalinensis) which may help distinguish the raw materials. Species distinction is crucial because only R. japonica is considered a pharmacopoeial raw material and is often collected from the wild. It is supposed that identification can be difficult with backcrosses of Reynoutria species, which may be morphologically similar to R. japonica. There is very little data on crossbreeding within the Reynoutria spp. and the phytochemical profile of hybrids. However, the probability of their occurrence in the environment is high due to the biology of knotweeds. In Europe, R. japonica is present mainly as a single, male-sterile, octoploid genotype, while R. sachalinensis and R. × bohemica exhibit higher genetic diversity and can reproduce sexually within and between taxa21. Both female specimens of R. japonica and R. sachalinensis can be fertilized with hybrid pollen (R. x bohemica) yielding seeds from backcrosses.

The development of molecular marker techniques has revolutionized plant genetic studies over the past few decades. Various markers, including RFLPs, RAPDs, AFLPs, ISSRs, SSRs, and SNPs, have gained widespread acceptance due to their stability, cost-effectiveness, and ease of use22,23. DNA-based markers have provided higher resolution in detecting genetic variations compared to traditional methods, enabling more precise estimates of genetic differences among individuals and populations24,25. The advent of next-generation sequencing has further enhanced marker discovery and application26. These molecular tools have proven valuable in various fields, including weed ecology, vector competence studies, and plant breeding25,27. Due to the tremendous growth in the availability of public biological databases, the development of functional markers that are located within or near the candidate genes has become considerably easy28. This has initiated a shift from random DNA markers to gene-targeted markers, resulting in the creation of novel marker systems such as Start Codon Targeted (SCoT) Polymorphism29 and the Sequence-Related Amplified Polymorphism (SRAP) technique30.

SCoT markers are designed based on the short, conserved region flanking the ATG start codon in plant genes, while SRAP markers focus on open reading frames (ORFs). Both SCoT and SRAP markers are classified as dominant markers. This means they cannot differentiate between homozygous dominant and heterozygous individuals, only indicating the presence or absence of a particular allele29,31,32. Nevertheless, similar to other dominant markers such as random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and inter simple sequence repeats (ISSR), SCoT and SRAP markers can be employed in genetic analysis, quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping, and bulk segregation analysis29. Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of SCoT and SRAP markers in assessing genetic diversity across various plant species. These markers have shown high polymorphism rates and superior performance compared to other molecular markers like RAPD and ISSR33,34,35. SCoT and SRAP markers have been successfully applied to analyze genetic diversity in safflower36, coffee37, Peganum harmala L.38, and Paris polyphylla Sm39. These markers provide valuable information for germplasm conservation, population genetics, and breeding programs.

SCoT markers were proved to be largely reproducible. The factors influencing SCoT marker reproducibility include primer GC content and 3’-end stability, rather than primer length or annealing temperature40,41. Additionally, SCoT markers have demonstrated higher resolution and variability in detecting genomic information than RAPD markers33,34.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that SRAP is highly effective for genetic diversity analysis, cultivar identification, and phylogenetic studies42,43,44 but like other dominant markers, they do not distinguish between different zygosity states45,46. Ferriol et al.42 found that the information provided by SRAP markers aligned more closely with morphological variability and the evolutionary history of the morphotypes than that provided by AFLP markers. Additionally, SRAP markers have shown higher effectiveness in several studies, as evidenced by their higher polymorphism information content in safflower36. Overall, SCoT and SRAP markers offer robust tools for genetic diversity analysis across various plant species.

The objectives of this study were to (1) analyze the morphological characteristics of these populations, (2) assess genetic variation and population structure across fifteen Reynoutria populations, (3) evaluate the chemical profiles of all individuals, and (4) determine the relationships between leaf morphology, genetic polymorphism, and chemical diversity within and among populations.

Results

Morphological analysis of Reynoutria specimens

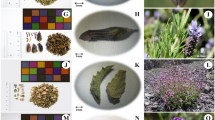

The morphological variation of 15 knotweed accessions was assessed in 150 middle-stem leaves (Supplementary Table 1) using a morphometric analysis, which has been considered the most reliable and widely used for knotweed identification13,47,48. Seven leaf characters were recorded for each specimen, out of which six were included in principal component analyses (PCA) and dendrogram construction (Fig. 1). The PCA was performed on datasets comprising morphological leaf characters related exclusively to the shape and size of the leaf lamina, excluding indumentum traits. Based on these six numerical characters, the analysis aimed to determine whether leaf shape and size alone are sufficient for identifying knotweed taxa, as trichome morphology is not readily observable in the field without a sufficiently magnifying glass.

Morphological analysis of 15 Reynoutria accessions using six numerical leaf characters. Principal component analysis (PCA) with loadings (A); Dendrogram (B); Boxplots of the variability of morphological characters between the three taxa. The boxes represent medians, Q1, and Q3, and whiskers show data ranges excluding outlying data (C).

Both PCA and dendrogram showed similar results (Fig. 1A and B). R. sachalinensis formed a distinct cluster, although data were too scarce to draw the ellipse. The hybrid R. × bohemica exhibited the greatest range of variation and was closely aligned with its parent taxon, R. japonica. The two latter taxa were not distinctly separated, resulting in overlapping clusters (Fig. 1A).

Hierarchical cluster analysis with the Euclidean distance measure and Ward’s clustering method constructed from morphological data grouped the fifteen Reynoutria individuals into three clusters (Fig. 1B). Notably, only the Giant Knotweed (represented by RS21, RS22, and RS23) formed a distinct branch. Despite a clear tridirectional structuring of the three taxa, noticeable overlaps were also present on the dendrograms. Morphologically similar R. japonica and R. × bohemica were not reliably separated. While they formed two clusters, individuals within them did not consistently correspond to a single species.

Loading plots and boxplots presenting six selected characters employed for the morphological analysis show that the dimensions vary between species (Fig. 1A and C). The parameters most effectively distinguishing R. sachalinensis from other species are leaf blade length and width. In contrast, the differentiation of R. japonica from R. × bohemica requires additional morphological parameters, as these species exhibit significant similarity in leaf characteristics. Accurate distinction between these species is achievable only when trichome morphology is also employed for analysis (Supplementary Table 1). Sample 15, although a hybrid, notably displays typical R. japonica morphology. Thus the most appropriate characters for separating knotweeds are leaf base width, leaf lamina width, leaf length, and petiolar sinus. According to Kruskal-Wallis analysis, only the apex width and length do not show statistically significant variation (Fig. 1C). Among the three species, R. japonica consistently has the smallest leaf dimensions. It is evident, that also the majority of leaves growing in the middle part of the stem exhibit considerable morphological variation. This is particularly visible in R. × bohemica, where leaves from the same stem can differ to such an extent that one may resemble the typical morphology of RJ, while another displays characteristics typical of RB.

Presented result suggests that morphological analysis alone is insufficient for the clear differentiation of R. japonica and R. × bohemica.

Genetic analysis of Reynoutria specimens

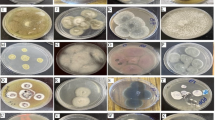

A total of thirty-six SCoT primers and sixty-six SRAP primer combinations were screened, out of which eighteen primers (Table 8) were able to amplify reproducible bands. These primers were employed to analyze genetic diversity and population structure.

To analyze the variability of Reynoutria spp. specimens, 18 sets of primers were used to study the SCoT and SRAP banding patterns across the populations. Nine selected SCoT primers produced 145 bands (16.11 bands per primer), of which 125 were polymorphic. Similarly, nine SRAP primer combinations produced 152 bands, with 135 being polymorphic (16.89 bands per primer). The percentage of polymorphic bands ranged from 70 to 91% for SCoT primers, with an average of 85%, and from 81 to 95% for SRAP primers, with an average of 89%. Among the SCoT primers, SCoT1 exhibited very high polymorphism and the highest resolving power (12.5). For the SRAP primers, the SRAP43 pair showed the highest polymorphism (95%), while SRAP32 had the highest resolving power (Rp) at 9.88, which strongly correlates with the ability to distinguish between genotypes. All of the SCoT and SRAP primers scored medium (0.1 to 0.25) to high (0.30 to 0.40) levels of polymorphism information content (PIC) (Table 2), which is considered differentiating for dominant markers.

Genetic diversity indices (Table 3) revealed that chosen genetic markers efficiently assess genetic variability within the genus Reynoutria. The average observed number of alleles per locus (Na) varied from 1.57 in Sakhalin knotweed to a relatively high 3.34 in bohemian knotweed, and an effective number of alleles (Ne) was low and almost identical for all species (~ 1.6). Nei’s gene diversity (H) indicated low genetic diversity (< 0.2) in all species with the highest value for hybrid (0.184). H values were similar for R. japonica and R. sachalinensis (0.101 and 0.106 respectively). Despite low H values, Shannon’s Information index (I) remains similar, with high values for R. japonica (5.21), R. x bohemica (5.28), and R. sachalinensis (5.45). The number of polymorphic loci (NPL) and percentage of polymorphic loci (PPL) for the hybrid (160 and 52.98%) were almost twice as high as for the parent species. The populations exhibited moderate Nei’s coefficient of gene differentiation (GST = 0.159) and a gene flow (Nm = 1.317). The AMOVA test showed that genetic variation observed within the populations was statistically significantly (p < 0.001) higher than variance among populations, as seen in both the combined data from SCoT and SRAP (53.04% vs. 46.96%, respectively) and in the analyses of individual markers (Table 4).

To better represent the relationship among the tested Reynoutria specimens, multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) and cluster analysis was performed based on combined SCoT and SRAP data (Fig. 2). The MCA (Fig. 2A) and dendrograms (Fig. 2B) revealed species-specific clustering of different knotweed genotypes. The cluster analysis dendrogram (Fig. 2B) categorized the samples into three clusters based on all polymorphic SRAP and SCoT fragments. While the dendrogram distinctly separates R. sachalinensis from the other species, R. × bohemica and R. japonica individuals exhibit considerable similarity. Although they form separate clusters, their close genetic relationship is evident, as seen in sample RB15, which is positioned within the R. japonica cluster. The UPGMA results were relative to the centers of similarity. The MCA analysis (Fig. 2A) revealed that the sample RJ2 was the only individual that diverged from the genetically cohesive R. japonica cluster, showing a shift towards R. × bohemica. R. sachalinensis formed a distinct and well-defined cluster, clearly separated from the other individuals. The hybrid group exhibited the greatest genetic diversity. Samples RB12, RB14, and RB18 were positioned closest to the center of similarity, while RB15 demonstrated a strong genetic affinity with R. japonica. In contrast, RB20 displayed a slight tendency towards R. sachalinensis, and RB13 and RB17 markedly differed from the other hybrid samples.

Following Structure Selector analysis, the maximum ΔK for the SCoT and SRAP marker data were observed at K = 2, and the 15 accessions, predefined into three populations, were grouped into two genetic groups (K = 2) (Fig. 2C). The Bayesian bar plot analysis revealed a clear genetic distinction for R. sachalinensis (red bars), while R. japonica formed a separate and well-defined genetic group (green bars) (Fig. 2D). Although a third distinct cluster was not identified, R. × bohemica accessions, centrally positioned in the bar plot, exhibit genetic admixture from both parental species, with a predominance of R. japonica (indicated by a more significant proportion of green color in the bars). These findings align with the cluster analysis dendrogram and MCA analysis, further confirming the distinct genetic structure of R. sachalinensis and the high genetic similarity between R. japonica and R. × bohemica, with the hybrid being the most genetically diverse.

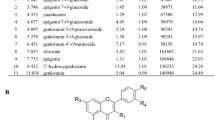

HPLC/DAD/ESI-HR-TOF-MS analysis

To determine the composition of the collected Reynoutria samples, qualitative HPLC/DAD/ESI-HR-QTOF-MS analyses were performed. The UHPLC-QTOF-MS analysis revealed a total of 117 detected compounds (Table 5) that belong to carbohydrates, stilbenes, flavan-3-ols, procyanidins, anthraquinones, organic acids, and naphthalenes. Among the 117 detected compounds, 26 remained unassigned and without a clear indication of their phytochemical nature and two were tentatively defined as carbohydrates.

Principal component analysis (PCA) was carried out using LC-MS data (peak intensities) acquired from 15 tested specimens. The visualization of the PCA scores plot shows similarities/dissimilarities between (PC1) and within (PC2) sample clusters. On the PCA scores plot (Fig. 3A) all samples identified as R. sachalinensis (RS21, RS22, RS23) were located on the left side of the plot, while almost all samples identified as R. japonica were located on the right side of the plot. According to the loading plot (Fig. 3B) compounds furthest to the left and right of the area are most responsible for this differentiation. The biggest impact on the created R. sachalinensis cluster was demostrated for phenylpropanoid derived disaccharide esters such as compund 60 (Hydropiperoside), 70 (Vanicoside C), 76 (Vanicoside B isomer), 86 (a Vanicoside B isomer), 54 (Tatariside A), 90 (Vanicoside A), 80 (Vanicoside B), 79 (Tatariside B), 65 (a Tatariside A isomer), 59 ((3,6-O-di-p-coumaroyl)-β- fructofuranosyl-(2→1)-(2’-O-acetyl-6’-O-feruloyl)-β- glucopyranoside), 93 (Tatariside C) present in these samples in the highest quantity. On the other hand, R. japonica has been influenced by many other compounds (located most to the right in the loading plot), out of which the most important are naphthalene derivatives, anthraquinones and stilbenes: 40 (a Torachrysone- hexoside), 48 (Sulfonyl torachrysone), 23 (Piceid), 47 (an unknown torachrysone derivative), 18 (a Peperomic ester), 95 (Emodin bianthrone-hexose), 53 (Emodin bianthrone-hexose-(malonic acid)-hexose), 58 (Emodin bianthrone-hexose-(malonic acid)-hexose), 85 (a Derivative of Emodinbianthrone-di-hexose), 107 (Emodin bianthrone), 30 (a Resveratrol hexoside), 20 (Resveratroloside), 28 (a Resveratrol hexoside).

Metabolic relationships among 15 Reynoutria genotypes based on LC-MS data for 117 compounds. Principal components analysis (PCA) plots indicating the general grouping of the variables in the data sets of extracts. The scores plot was computed using the first two principal components (PC1–40.3% vs. PC2-18.6%). Cumulative variance = 91.65988% for 8 components. (A); Loading plot of PCA results obtained from LC-MS data. Numbers represent the compounds listed in Table 5 (B); Dendrogram constructed based on LC-MS data for 117 compounds (C).

The samples from R. x bohemica are closer to the center of the PCA score plot, indicating that phenylpropanoid derivatives as well as naphthalenes, anthraquinones and stilbenes had comparably significant effect on their distribution between the left and right sides of the plot (Fig. 3A). However, it can be noted that two samples are located much further from the center. Sample RB17 is located closer to R. sachalinensis, which clearly differs in terms of chemical composition from sample RB13, located far from the center on the right side of the area. Dissimilarities between the samples distributed on the left or right side of the PCA scores plot are explained by PC2. Most of the R. japonica samples are located in the fourth quadrant, and their position was influenced by such compounds as 34 (Emodin-glucoside), 42 (Emodin-glucoside), 87 (Questin), 33 (Aloesone hexoside). Sample RJ2 is located at the lowest in the fourth quadrant, indicating the significant content of these compounds, which differentiates it from the other R. japonica samples. Sample RJ31 is clearly on the opposite side from RJ2, indicating significant differences between them. The position of sample RJ31 was most influenced by compounds located in the third quadrant. Most of the R. x bohemica samples are in the second and third quadrants of the PCA chart, with the exception of RB20. A position near the center of the plot indicates a similar influence of compounds or a slight influence of compounds distributed on the edges of the loading plot.

PCA analysis showed that only samples from R. sachalinensis formed a separate, distinct cluster. Among R. x bohemica and R. japonica specimens, samples stood out from the rest, making it impossible for them to form separate clusters.

Similarly, the cluster analysis dendrogram (Fig. 3C) categorized the samples into two distinctive clusters based on LC-MS data for 117 compounds. As in the PCA analysis, only samples from R. sachalinensis formed a separate cluster, with other samples being clustered together and categorized into subclusters formed by a mix of RB and RJ samples.

HPLC/DAD/ESI-HR-TOF-MS quantitative analysis

Quantitative HPLC/DAD/ESI-HR-TOF-MS analysis was conducted for 15 Reynoutria specimens. The abundance of six compounds such as: piceid, resveratrol, vanicoside A, vanicoside B, emodin and physcion was determined in the rhizomes of analyzed Reynoutria samples (Table 6).

The content of six quantified compounds clearly differs between samples from R. sachalinensis and R. japonica. R. x bohemica, on the other hand, contains their intermediate quantities. The most abundant compound turned out to be piceid, which has been found exclusively in rhizomes of R. japonica and R. bohemica. In the rhizomes of R. sachalinensis, piceid and resveratrol were below the detection level. Despite of that, neither the PCA analysis nor the dendrogram constructed with the six quantified compounds, did not allowed for the unequivocal differentiation between analyzed Reynoutria accessions (Fig. 4).

Sample RJ06 is more similar to other R. x bohemica samples, probably due to its relatively low resveratrol, piceid, emodin and physcion content and relatively high vanicoside A and B content (Table 6). The opposite trend is observed in sample RB13, where very low content of vanicosides was observed, which makes this sample similar to other R. japonica samples.

Discussion

Recent studies have deepened our understanding of the taxonomy and identification of Reynoutria species, revealing significant challenges due to their complex morphological, cytological, and genetic diversity. Morphological analysis alone is often insufficient for accurately distinguishing species, primarily due to extensive genetic and phenotypic variability55. For instance, R. × bohemica exhibits intermediate traits between its parent species but resembles R. japonica10,56. These variations are critical in understanding invasion dynamics and management strategies57,58.

Key morphological features used for differentiation include leaf shape, trichome characteristics, and base/apex morphology. Japanese knotweed has broadly ovate leaves with a straight or slightly rounded base and sharply pointed apex. Giant knotweed features heart-shaped leaves with a deeply heart-shaped base and pointed ends, while Bohemian knotweed shows intermediate traits, often making it difficult to distinguish without detailed examination. Hybrids can be recognized by intermediate leaf and stand size, slightly cordate leaf bases, and variations in trichome morphology8. Leaf indumentum has been suggested as the most reliable distinguishing feature10. However, there is no single trait that would allow for clear differentiation between taxa2,10,11. Furthermore, the utility of morphological traits diminishes in regions with diverse hybrid populations, where morphological characteristics often overlap, complicating identification59. The collection site of studied plants (Fig. 6) is one of many regions in Europe, where cross-pollination between different taxa of Reynoutria occurs producing varied populations of hybrids.

While anatomical characteristics can help differentiate some species60, hybridization and polyploidy further complicate identification61,62. Although cytological studies have revealed varying ploidy levels across the genus, there is no consistent correlation between ploidy and morphological traits11. R. japonica is typically octoploid, R. sachalinensis ranges from tetraploid to hexaploid, and R. × bohemica is generally hexaploid2,11. Hybridization and introgression events further increase genetic complexity12,59. Cytogenetic analysis can be challenging due to the small, undifferentiated chromosomes, requiring advanced techniques like fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for accurate analysis63.

Genetic diversity studies in Reynoutria species reveal intricate patterns. While early research indicated low diversity in invasive R. japonica populations in Europe62,64, recent genomic analyses suggest considerable genetic variation within this taxon in North America65. In contrast, R. sachalinensis and the hybrid R. × bohemica consistently exhibit higher genetic variability across studies62,64,65. This diversity is likely shaped by multiple introductions and hybridization events65. Genetic diversity within Reynoutria has been further elucidated using markers such as SNP, nuclear genes LEAFY, and isozyme analyses, revealing significant variability, especially in hybrids57,59,66. These approaches reveal cryptic genetic diversity and complex hybridization dynamics in invasive Reynoutria populations, underscoring the need for further research to elucidate the genetic mechanisms underlying their invasive success. This diversity is closely tied to the species’ invasive potential and regeneration abilities66. Despite progress in genetic studies, differentiating hybrids with varying ploidy levels remains difficult67.

Chemical profiling, particularly using high-performance separation methods like liquid or gas chromatography, has long been a valuable tool in distinguishing of species and infraspecific variants such as chemotypes, chemical races or to detect admixtures and adulterations. Additionally, using LC-MS data processing and analysis platforms, often available online and free of charge, chemical profiling can become fast, reliable and useful for species identification. Moreover, this identification method is advantageous especially for the authentication of pharmacopoeial raw material, such as the rhizomes, which are separated from the aerial parts and often dried and where the information about other morphological features is missing.

In Reynoutria species HPLC and LC-MS analytical studies revealed distinct phytochemical compositions18,19. In this work, we have demonstrated that R. sachalinensis is distinguished by the impact of phenylpropanoid disaccharide esters such as hydropiperoside, vanicosides, tatarisides, and their isomers (Fig. 3B). This observation is consistent with our earlier studies, where a significantly higher content of these compounds was demonstrated in R. sachalinensis than in R. japonica and R. x bohemica18,19. We have also proved that R. japonica separates mainly by a higher content of naphthalene derivatives, anthraquinones and stilbenes (Fig. 3B). Such findings support the role of chemical profiling as an important complementary tool to morphological and genetic analyses. However, some other fingerprinting methods, such as HPTLC did not allow to clearly distinguish these three taxons as in Bensa and co-workers who compared flavan-3-ol profiles using several mobile and stationary phases on HPTLC plates68. As it was shown, all three species had similar qualitative profiles and only quantitative differences were observed. Thus, sole phytochemical fingerprinting is insufficient to obtain reliable discrimination between the hybrid and the parent species.

To address the limitations of traditional morphological analysis, combining chemical profiling, cytogenetics, and genetic techniques such as targeted fingerprinting offers a more comprehensive framework for species identification. Polymorphism Information Content (PIC) and resolving power (Rp) are key metrics used to assess the effectiveness of genetic markers. PIC, first introduced by Botstein et al.69 for linkage studies, is nowadays widely used in genetic diversity and genome-wide association studies to assess marker usefulness70 as it corresponds to the markers’ ability to detect polymorphisms among individuals in a population71. Higher PIC values reflect a greater capacity for distinguishing between genotypes. For dominant markers, the maximum PIC value is 0.572,73,74. PIC analysis has practical applications in various fields, including plant breeding and conservation genetics, as demonstrated in studies on Citrullus colocynthis in Iran75. Several equations exist for calculating PIC, with variations for dominant and co-dominant markers71. Allele frequencies influence PIC values and can vary between breeds within a species76. In this study, all of the SCoT and SRAP primers scored medium (0.1 to 0.25) to high (0.30 to 0.40) levels of PIC which is considered differentiating for dominant markers (Table 2) and makes them a suitable tool for studying genetic diversity. Resolving power (Rp) measures a marker system’s discriminatory ability by calculating the number of genotypes that can be separated based on specific markers within a population77. High PIC and Rp values reflect greater marker efficiency and informativeness in population genetics. Both, PIC and Rp metrics are thus crucial for assessing the efficiency, effectiveness, and potential of marker systems in population genetics and molecular biology.

The number of bands produced per primer also serves as an indicator of marker informativeness. Higher band production correlates with an increased ability to detect polymorphisms, which is crucial in distinguishing genotypes and cultivars78. In our study, SCoT1 exhibited the highest polymorphism and resolving power (12.5). For the SRAP primers, the SRAP43 pair showed the highest polymorphism (95%), while SRAP32 had the highest resolving power (Rp) at 9.88. The percentage of polymorphic bands ranged from 70 to 91% for SCoT primers, with an average of 85%, and from 81 to 95% for SRAP primers, with an average of 89%, which is considered relatively high (Table 2).

Low genetic diversity in all analyzed species (expressed as Nei’s gene diversity index H < 0.2) suggests their limited genetic variation and potential vulnerability to environmental changes. The low H values in invasive species indicate they may have undergone a genetic bottleneck, possibly due to clonal reproduction, limited introductions, or strong selection pressures79,80. The hybrid shows higher genetic diversity (H = 0.184) than both parent species (H = 0.101 and 0.106), which is expected due to hybridization. Increased heterozygosity in hybrids can provide greater adaptability and fitness, potentially explaining its invasive success81,82. The lower genetic diversity within R. japonica and R. sachalinensis populations may limit adaptability to changing environments, making them more reliant on phenotypic plasticity rather than genetic variation. Shannon’s Information Index (I) is correlated with Nei’s gene diversity but generally provides a more comprehensive view by incorporating allelic frequency distribution. Shannon’s index values for R. japonica (I = 5.21), R. × bohemica (I = 5.28), and R. sachalinensis (I = 5.45) indicate high genetic diversity across all analyzed species. Shannon’s index accounts for both genetic richness and evenness, meaning higher values suggest more significant genetic variation within populations. These results indicate that while Nei’s gene diversity suggests genetic uniformity, Shannon’s index might highlight the presence of rare alleles or higher complexity among studied accessions, particularly, rather than widespread variation. The number of observed alleles (Na) suggests moderate to high diversity in R. × bohemica (3.34) but lower diversity in R. japonica (2.60) and R. sachalinensis (1.57). The rather low effective number of alleles (Ne = ~ 1.6) reveals constrained genetic diversity across all species, indicating that allelic richness exists, but allele frequencies are not evenly distributed. NPL and PPL values confirm that R. × bohemica exhibits significantly higher genetic diversity than its parent species, likely due to hybridization. In contrast, the relatively low genetic diversity in R. japonica and R. sachalinensis suggests clonal reproduction and possible genetic bottlenecks, which may limit their evolutionary potential79. Since Nei’s coefficient of gene differentiation (GST = 0.159) is on the boundary between moderate and high83, populations exhibit some genetic distinctiveness while still maintaining shared genetic variation. Gene flow (Nm) can decrease local adaptation by homogenizing populations that grow in different habitats84. For studied Reynoutria populations, Nm = 1.317 means the gene flow is still occurring but not at a high enough rate to homogenize populations completely. The moderate to high genetic differentiation and gene flow observed in Reynoutria populations align with the species’ primary mode of vegetative reproduction. Vegetative reproduction, such as clonal growth through rhizomes, typically limits genetic variation within individual clones but can allow for some genetic exchange between geographically separated individuals or populations, primarily through mechanisms like pollen transfer or seed dispersal85,86. The observed moderate differentiation suggests that although populations are primarily clonal, genetic diversity is maintained, likely due to occasional sexual reproduction and limited gene flow. This gene flow rate prevents the complete isolation of species through genetic connectivity and allows for their local adaptation and differentiation.

In this work, cluster analysis dendrograms were created to categorize the Reynoutria samples based on their morphological traits (Fig. 1B), chemical composition (Figs. 3C and 4C), and genetic diversity (Fig. 2B). Correlations between all dendrograms are presented in Fig. 5.

Metabolic relationships among 15 Reynoutria genotypes based on quantitative analysis of six compounds. Principal components analysis (PCA) plots indicating the general grouping of six variables in the data sets of extracts. The scores plot was computed using the first two principal components (PC1–64.9% vs. PC2–19.1%) (A); Loading plot of PCA results obtained from LC-MS data for six quantified compounds. (B); Dendrogram constructed based on LC-MS data for six quantified compounds (C).

The highest correlation between dendrograms was observed between genetic and morphological data, with values of 0.85 (according to Baker’s methodology) (Fig. 5D). The genetic dendrogram corresponded with the morphological dendrogram analysis but confirmed the problematic affiliation of several specimens (Fig. 5A). For example, sample RB15 aligns closely with R. japonica in both genetic and morphological analyses. However, sample RJ10, despite being morphologically ambiguous and clustering with R. × bohemica, is genetically a typical R. japonica. This does not prove a genetic method’s inability but implicates the possibility of cross-breeding between hybrids and one of the parental organisms, though there is no doubt that Sakhalin knotweed is a distinct clade, morphologically chemically and genetically.

Correlation analysis of dendrograms in Reynoutria generated using genetic, metabolomics (117 compounds), and morphological data sets. Comparison of genetic and morphological dendrograms (A), genetic and metabolomic dendrograms (B), metabolomic and morphological dendrograms (C), and graphical representation of Baker’s correlation coefficient for genetic, morphological, and metabolomic (117 and 6 compounds) dendrograms (D).

Lower correlations were noted between genetics and metabolomics, as well as between morphology and metabolomics. The genetic and metabolomic dendrogram (Fig. 5B) comparison supports the distinct clustering of R. sachalinensis. Chemically, RB15 shows more similarities to R. japonica, and RJ10 reaffirms its genetic link to R. japonica, despite its morphological discrepancies.

The greatest inconsistencies among the comparative analyses arose from the metabolomic and morphological comparisons (Fig. 5C). While R. sachalinensis was distinctly differentiated, attempts to correlate the remaining individuals with their respective species were confusing. Moreover, the analysis based on only six key chemical compounds proved insufficient, making it impossible to establish a meaningful dendrogram correlation.

Morphological markers are visual indicators that were often reported insufficient in raw material identification. Chemical profiling has long been a valuable tool in distinguishing of species, however a sole phytochemical fingerprinting has been proven unsatisfactory to obtain reliable discrimination between the hybrid and parent species. Unlike plant genetic features, both, plant morphology and plant metabolome are phenotypic characteristics resulting from the activity of particular genes and influenced throughout the plant life by various environmental factors.

Conclusions

This study explored genetic identity, diversity, and population structure using SRAP and SCoT markers correlated with morphological characteristics and LC-MS-based phytochemical profiles in three invasive Reynoutria species. The comprehensive investigation supported the combined approach’s effectiveness in assessing the origin of plant material, especially the identity of the pharmacopeial herbal drug Polygoni cuspidate rhizome et radix (R. japonica rhizomes).

It has also been shown that phytochemical differences between R. × bohemica and R. japonica are less significant, in contrast to R. sachalinensis. Therefore, the rhizome raw material from R. × bohemica may be suitable for medicinal use, as they share comparable chemical properties with R. japonica. This supports the potential application of R. × bohemica as an abundant source of bioactive constituents or as a whole herbal drug with limitations regarding specific pharmacopoeial guidelines.

Morphologically similar plants may not be genetically related and the profile of bioactive phytochemicals may be entirely dissimilar. Therefore, a characterization of molecular features should be included in recommended identification procedures to minimize the risk of mistakes or unexpected pharmacological properties. Moreover, the complex identification and discrimination methods can aid in field studies and assessing spread, diversity and evolution of the invasive species, which is a prerequisite for sustainable environmental management.

Methods

Plant material

Our study investigated three invasive knotweed taxa collected in the urban environment of Wroclaw, Poland. The samples were collected from fifteen distinct populations across various geographical locations, and they were classified based on their leaf shape and size, trichome type and morphology12. To evaluate the patterns of genetic variation in the Reynoutria genus, leaf material was obtained from a total of 15 plant individuals representing: five R. japonica, seven R. × bohemica, and three R. sachalinensis populations. Rhizomes from the same specimens were collected for phytochemical analysis. Voucher specimens of all taxa have been deposited at the Herbarium of the Botanical Garden of Medicinal Plants, Wroclaw Medical University (Poland). Figure 6; Table 7 detail the collected information for examined samples.

The plants investigated in this study have been collected by the botanic garden staff who act according to the Ministry of Environment, decision number: DOPozgiz-4210-26-6024-05/KL. The plants have been formally identified by the Botanic Garden of Medicinal Plants curator, Klemens Jakubowski MSc.

Morphological analysis

Only plants exceeding 1.5 m in height were included in the study. Ten fully mature, mid-branch leaves were collected from each plant (in the middle of the stem the shape of the leaves is most characteristically developed). Leaf blade length and width were measured as overall indicators of size. Leaf apex morphology (length and width) and leaf base width and shape (petiolar sinus) were also examined. Trichome morphology was assessed at 100x magnification and categorized into three classes based on trichome height, cell number and basal cell morphology following descriptions by Gammon et al. and Zika et al.12,47. Based on these observations, each sample was identified as R. sachalinensis, R. × bohemica, or R. japonica according to Table 1 criteria. Individuals not fully matching parental traits were labeled as R. × bohemica. Hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted on morphological traits using the R packages ‘stats’ r core87 and ‘dendextend’88, employing the Euclidean distance measure and Ward’s clustering method. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate the statistical significance of morphological data.

Genomic DNA isolation

Young leaves from each of the 15 plant individuals were collected and dried for 3 h at 55 °C. After grinding in liquid nitrogen, total DNA was extracted using the Plant/Fungi DNA Isolation Kit (Norgen Biotek). The DNA concentration was measured with a NanoDrop™ 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific™). The quality of DNA was estimated by agarose gel electrophoresis.

SRAP and SCoT PCR amplification

All PCR reactions were performed within a total volume of 20 µl containing genetically engineered thermophilic Hybrid DNA polymerase (EURx, Poland), approximately 50 ng of genomic DNA, and 0.5 µmol of each primer (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The primer sequences, parameters, and combinations of markers are illustrated in Table 8. Both, SRAP and SCoT markers were amplified by gradient Bio-Rad T100 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, USA). The amplicons were separated on 1.5% agarose gels using Perfect™ 100 bp DNA Ladder as standard (EURx, Poland) in a Tris Acetate-EDTA (TAE) buffer at 7 V/cm, stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under UV light with G: BOX Chemi XRQ gel doc system (Syngene, UK).

Initially, 66 SRAP primer combinations were used to amplify 15 genomic DNA templates of Reynoutria spp. From those, nine primer combinations: me1 + em1 (SRAP11), me1 + em5 (SRAP15), m32 + em2 (SRAP22), me2 + em3 (SRAP23), me2 + em5 (SRAP25), me3 + em2 (SRAP32), me3 + em5 (SRAP35), me4 + em3 (SRAP43), me4 + em5 (SRAP45) were selected as they provided the greatest reproducibility and the highest number of bands per gel (Table 2).

According to the primer sequences designed by Collard and Mackill29, all of the 36 SCoT primers were synthesized and tested and nine primers with clearly separated bands, stable amplification, and rich polymorphism were selected for further analysis (Table 2).

Due to the polymerase modification, the optimal reaction conditions differed from standard SCoT and SRAP PCR protocols29,30. SRAP amplification thermal cycling conditions were as follows: 30 s of initial denaturing at 98 °C, 35 cycles of 10 s at 98 °C, 30 s at 35 °C for the five initial cycles, and 50 °C for the next 30 cycles, and 2 min at 72 °C; this was followed by a final extension of 7 min at 72 °C. SCoT PCR amplifications (as it is a single primer reaction) were programmed as follows: an initial denaturation step at 98 °C for 30 s followed by 35 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s, 50 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 2 min; the final extension was at 72 °C for 7 min.

Molecular data analysis

The molecular analysis of SRAP markers was done according to the procedure described by Li and Quiros30 with some modifications. All SRAP primer combinations were initially screened using a group of all 15 samples89. The combinations of nine SRAP primers that output scorable polymorphic bands were used to amplify all accessions (Table 8).

The molecular analysis of SCoT markers was done according to the procedure described by Collard and Mackill29. All SCoT primers were first screened using a group of all 15 samples. The nine primers that output scorable polymorphic bands were used to amplify all accessions (Table 8).

PCR amplified SCoT and SRAP fragments were detected on agarose gel based on the relative standard size (Perfect™ 100 bp DNA Ladder as standard (EURx, Poland)) using Cliqs v1.5 software (Total Lab, UK). An example of agarose gel analysis is provided in Supplementary Fig. 1. Bands were scored as 1 (present) or 0 (absent) and a binary data matrix was generated (Supplementary Table 2). Vague bands that could not be easily detected were not scored. Accessions pairwise comparisons were calculated using the Jaccard’s similarity coefficient: DJ=2nxy/nx + ny, where nx is the number of bands present within accession x, ny is the number of bands present within accession y, and nxy is the number of bands shared by accessions x and y90,91. Cluster analysis based on molecular data was performed using the Jaccard’s similarity index and Ward’s clustering method with the use of the tools listed in Sect. 2.2.

Genetic relationships among the genotypes were analysed by the multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) using the R-package ‘FactoMineR’92. The MCA is an appropriate tool for analysing categorical data92. In order to investigate the efficiency of the selected primers, informativeness indices, such as the number of polymorphic bands, Resolving power (Rp), and mean PIC value, were estimated. Polymorphism information content was calculated for each primer using a simplified formula for dominant markers PIC = 1 – (p2 + q2) where p and q are the population frequency of the ith and jth allele69,71. The ability of the SCoT and SRAP primers to distinguish between genotypes was accessed by calculating the Resolving Power (Rp)93, using the formula Rp = ΣIb where band informativeness, Ib = 1 − (2 × |0.5 − p|) and p is the proportion of genotypes containing band I. To assess species-level genetic diversity R-packages ‘poppr’94 and ‘adegenet’95 were employed to compute various parameters, including the average number of observed (Na) and effective alleles (Ne)96, the number (NPL) and percentage (PPL) of polymorphic loci, Nei’s gene diversity/expected heterozygosity (H)97Shannon’s information index (I)98, and Nei’s coefficient of gene differentiation (GST). The gene flow was then estimated using the formula Nm = ((1/ GST) – 1)/4100. Additionally, an Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) was also performed to quantify genetic variation within and between populations for both markers using the same R packages.

A Bayesian clustering approach was employed to identify genetically similar groups of accessions, with Bayesian bar plots generated using STRUCTURE software v2.3.4100. The optimal number of genetic groups (K) was estimated based on 10 independent runs for each K value ranging from 1 to 10. The admixture model was applied with 100,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) iterations and a burn-in period of 10,000. According to Evanno et al., the most probable K value was determined using the ΔK method101 via the StructureSelector web server102.

Sample preparation for qualitative and quantitative analysis

Reynoutria spp. rhizomes were collected in the last week of October 2021 in Wroclaw (Poland) from the locations specified in Table 7. 200 milligrams of air-dried and powdered rhizomes of each sample were extracted three times with 5 mL of acetone: H2O (7:3 v/v) in an ultrasonic bath for 30 min at 25 °C. The extracts were separated from the plant materials by decantation after prior centrifugation. The supernatant was collected, evaporated to dryness, and lyophilized. Extracts were dissolved in 80% of MeOH to obtain a concentration of 5 mg dry weight/mL. After filtering the solutions through a 0.22 μm PTFE syringe membrane (Chromafil, Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) into vials, 4 µL of the sample was injected by an autosampler into the Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography system combined with quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometry (UHPLC-QTOF-MS). All determinations were done in triplicate (biological replication meaning an independently prepared extract n = 3); each biological replication was measured at least twice as a technical replication.

A previously developed, validated analytical method was used to quantify the six compounds: vanicoside B, vanicoside A, resveratrol, piceid, emodin and physcion18. Linearity, the LOD (limit of detection), and LOQ (limit of quantification) for all quantified compounds were presented in our previous study18.

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis

Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometry (UHPLC-QTOF-MS) analysis of all samples was carried out on a Thermo Ultimate 3000 RS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) chromatographic system coupled to a Bruker Compact (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) quadrupole time of flight (QTOF) mass spectrometer, consisting of a binary pump, sample manager, column manager, and the PDA/diode array detector. Separations were performed on a Kinetex C18 column (2.1 × 150 mm, 2.6 μm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) maintained at 30 °C. Mobile phase A (H2O: HCOOH, 100:0.1, v/v) and B (acetonitrile: HCOOH, 100:0.1, v/v) were used in a following gradient program: 0–22 min 15–50% B, 22–28 min 50–95% B, 28–33 min 95% B, 33–35 min 95 − 15% B followed by column equilibration with 15% B for 2 min between injections. The flow rate was 0.3 mL/min. Analysis of all samples was repeated at least two times as consecutive injections. UV-Vis spectra were recorded in the range of 200–450 nm. Chromatograms were acquired at 298 nm. High-resolution quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer was equipped with electrospray ionization (ESI-HR-QTOF-MS). ESI-MS conditions were as follows: splitless, nebulizer pressure 30 psi; dry gas flow 8 L/min; dry temperature 250 °C; and capillary voltage 2.2 kV for negative ion mode and 4.5 kV for positive ion mode (for physcion). Mass spectra were recorded using scan range (m/z) of 50–2200. The collision energy was set automatically from 20 to 40 eV, depending on the m/z of the fragmented ion. The identification of constituents found in plant materials was based on MS1 (accurate mass) and MS2 spectra which were compared with a library.

For statistical analysis raw data obtained from UHPLC-QTOF-MS (DataAnalysis 4.2, Bruker) analysis were converted by MSConvert (ProteoWizard) to mzML format.

Next, all data were uploaded into the XCMS Online platform (https://xcmsonline.scripps.edu/landing_page.php?pgcontent=mainPage). The single job analysis was chosen. All parameters selected for processing the job are presented in Supplementary Table 3. Result table with features (after reducing their number by removing those with the lowest intensity to 117) were used for statistical analysis. Table with features is presented in the Supplementary Table 4. Among the 117 features included in the statistical analysis, most were tentatively identified.

Data availability

Morphological and molecular data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. The UHPLC-QTOF-MS raw data generated and analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Alberternst, B. & Böhmer, H. J. NOBANIS – Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet - Fallopia japonica. From: Online Database of the European Network on Invasive Alien Species – NOBANIS. Accessed 16 Apr 2013. https://www.nobanis.org/ (2011).

Jugieau, E., Talmot, V., Staentzel, C., Noir, S. & Hardion, L. A knot of hybrids: Differentiating Asian knotweeds in North-Eastern France using genetic, cytological, and morphological data. J. Syst. Evol. 62(6), 1218–1226 (2024).

Desjardins, S. D., Pashley, C. H. & Bailey, J. P. A taxonomic, cytological and genetic survey of Japanese knotweed s.l. in New Zealand indicates multiple secondary introductions from Europe and a direct introduction from Japan. N Z. J. Bot. 61, 49–66 (2023).

Tokarska-Guzik, B. The Establishment and Spread of Alien Plant Species (Kenophytes) in the Flora of Poland. (Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego, 2005).

Tynkevich, Y. O., Yakobyshen, D. V., Cherkazianova, A. S., Shelyfist, A. Y. & Volkov, R. A. Intragenomic polymorphism of the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 region in invasive species of the genus Reynoutria. Cytol. Genet. 58, 536–546 (2024).

Drazan, D., Smith, A. G., Anderson, N. O., Becker, R. & Clark, M. History of knotweed (Fallopia spp.) invasiveness. Weed Sci. 69, 617–623 (2021).

Chrtek, J. & Chrtková, A. Reynoutria × bohemica, nový kříženec z čeledi rdesnovitých. Časopis Národního Muzea v Praze Rada Přírodovědna. 152, 120 (1983).

Bailey, J. & Wisskirchen, R. The distribution and origins of Fallopia x bohemica (Polygonaceae) in Europe. Nord J. Bot. 24, 173–199 (2004).

Pashley, C. H. The use of Molecular Markers in the Study of the Origin and Evolution of Japanese Knotweed Sensu lato (University of Leicester, 2006).

Mereďa, P., Koláriková, Z. & Hodálová, I. Cytological and morphological variation of Fallopia sect. Reynoutria taxa (Polygonaceae) in the Krivánska Malá Fatra Mountains (Slovakia). Biol. (Bratisl). 74, 215–236 (2019).

Kim, J. Y. & Park, C. W. Morphological and chromosomal variation in Fallopia section Reynoutria (Polygonaceae) in Korea. Brittonia 52, 34–48 (2000).

Gammon, M. A., Grimsby, J. L., Tsirelson, D. & Kesseli, R. Molecular and morphological evidence reveals introgression in swarms of the invasive taxa Fallopia japonica, F. Sachalinensis, and F. x Bohemica (Polygonaceae) in the United States. Am. J. Bot. 94, 948–956 (2007).

Fojcik, B. & Tokarska-Guzik, B. Reynoutria × bohemica (Polygonaceae) - nowy takson we florze Polski. Fragm Flor. Geobot Pol. 07, 63–71 (2000).

Ke, J. et al. Advances for pharmacological activities of Polygonum cuspidatum - A review. Pharm. Biol. 61, 177–188 (2023).

European Pharmacopoeia. 9th ed. Strasburg, 1481–1483 (European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines, 2017).

Fan, P., Terrier, L., Hay, A. E., Marston, A. & Hostettmann, K. Antioxidant and enzyme inhibition activities and chemical profiles of Polygonum sachalinensis F.Schmidt ex Maxim (Polygonaceae). Fitoterapia 81, 124–131 (2010).

Strašil, Z. & Kára, J. Study of knotweed (Reynoutria) as possible phytomass resource for energy and industrial utilization. Res. Agric. Eng. 56, 85–91 (2010).

Nawrot-Hadzik, I., Granica, S., Domaradzki, K., Pecio, Ł. & Matkowski, A. Isolation and determination of Phenolic glycosides and anthraquinones from rhizomes of various Reynoutria Species. Planta Med. 84, 1118–1126 (2018).

Nawrot-Hadzik, I., Slusarczyk, S., Granica, S., Hadzik, J. & Matkowski, A. Phytochemical diversity in rhizomes of three Reynoutria species and their antioxidant activity correlations elucidated by LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis. Molecules 24, 1136 (2019).

Nawrot-Hadzik, I. et al. Chemical composition of east Asian invasive knotweeds, their cytotoxicity and antimicrobial efficacy against cariogenic pathogens: An in-vitro study. Med. Sci. Monit. 25, 3279–3287 (2019).

Holm, A. K. et al. Low genetic variation of invasive Fallopia spp. in their northernmost European distribution range. Ecol. Evol. 8, 755–764 (2018).

Grover, A. & Sharma, P. C. Development and use of molecular markers: Past and present. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 36, 290–302 (2016).

Semagn, K., Bjørnstad, Å. & Ndjiondjop, M. N. An overview of molecular marker methods for plants. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 5, 2540–2568 (2006).

Cruzan, M. B. Genetic markers in plant evolutionary ecology. Ecology 79, 400–412 (1998).

O’Hanlon, P. C., Peakall, R. & Briese, D. T. A review of new PCR-based genetic markers and their utility to weed ecology. Weed Res. 40, 239–254 (2000).

Raza, K. & Ahmad, S. Principle analysis, application and challenges of next-generation sequencing: A review. arXiv Preprint. 19, 1–29 (2016).

Severson, D. W. Applications of molecular marker analysis to mosquito vector competence. Parasitol. Today. 10, 336–340 (1994).

Andersen, J. R. & Lübberstedt, T. Functional markers in plants. Trends Plant. Sci. 8, 554–560 (2003).

Collard, B. C. Y. & Mackill, D. J. Start Codon targeted (SCoT) polymorphism: A simple, novel DNA marker technique for Generating Gene-targeted markers in plants. Plant. Mol. Biol. Rep. 27, 86–93 (2009).

Li, G. & Quiros, C. F. Sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP), a new marker system based on a simple PCR reaction: Its application to mapping and gene tagging in Brassica. Theor. Appl. Genet. 103, 455–461 (2001).

Rai, M. K. Start codon targeted (SCoT) polymorphism marker in plant genome analysis: Current status and prospects. Planta 257, 1–19 (2023).

Al-Yasi, H. M. & Al-Qthanin, R. Comparing genetic differentiation and variation using ISSR and SCoT among Juniper plant markers in Saudi Arabia. Front. Plant. Sci. 15, 1–9 (2024).

Saidi, A., Daneshvar, Z. & Hajibarat, Z. Comparison of genetic variation of Anthurium (Anthurium andraeanum) cultivars using SCoT, CDDP and RAPD markers. Plant. Tissue Cult. Biotechnol. 28, 171–182 (2018).

Hromadová, Z. et al. Efficiency of RAPD and SCoT markers in the genetic diversity assessment of the common bean. Plants 12, (2023).

Ahmed, T. Y. A., Hussein, M. H., El-Maaty, S. A. & Moghaieb, R. E. A. Detection of genetic variation among five basil species by using ISSR, SCOT and SRAP markers. Int. J. Health Sci. (Qassim). 6, 9909–9922 (2022).

Golkar, P. & Mokhtari, N. Molecular diversity assessment of a world collection of safflower genotypes by SRAP and SCoT molecular markers. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 24, 1261–1271 (2018).

Huded, A. K. C., Jingade, P., Bychappa, M. & Mishra, M. K. Genetic Diversity and Population structure analysis of Coffee (Coffea canephora) germplasm collections in Indian Gene Bank employing SRAP and SCoT markers. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 20, S757–S784 (2020).

Gholami, T., Peyvandi, M., Abbaspour, H., Noormohammadi, Z. & Sharifnia, F. Genetic variability analysis in Peganum harmala L. by SCoT and SRAP molecular markers. Genetika 51, 1021–1030 (2019).

Zhao, X. et al. Genetic relationships and diversity among populations of Paris polyphylla assessed using SCoT and SRAP markers. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 26, 1281–1293 (2020).

Bhattacharyya, P., Kumaria, S., Kumar, S. & Tandon, P. Start Codon targeted (SCoT) marker reveals genetic diversity of Dendrobium Nobile Lindl., an endangered medicinal orchid species. Gene 529, 21–26 (2013).

Vanichanon, A., Blake, N. K., Martin, J. M. & Talbert, L. E. Properties of sequence-tagged-site primer sets influencing repeatability. Genome 43, 47–52 (2000).

Ferriol, M., Picó, B. & Nuez, F. Genetic diversity of a germplasm collection of Cucurbita pepo using SRAP and AFLP markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 107, 271–282 (2003).

Ferriol, M., Picó, B. & Nuez, F. Morphological and molecular diversity of a Collection of Cucurbita maxima Landraces. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 129, 60–69 (2004).

Budak, H., Shearman, R. C., Parmaksiz, I. & Dweikat, I. Comparative analysis of seeded and vegetative biotype buffalograsses based on phylogenetic relationship using ISSRs, SSRs, RAPDs, and SRAPs. Theor. Appl. Genet. 109, 280–288 (2004).

Li, G. & McVetty, E. P. B. & F., C. SRAP molecular marker technology in Plant Science. in Plant Breeding from Laboratories to Fields (InTech, 2013) https://doi.org/10.5772/54511.

Aneja, B., Yadav, N. R., Chawla, V. & Yadav, R. C. Sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP) molecular marker system and its applications in crop improvement. Mol. Breeding. 30, 1635–1648 (2012).

Zika, P. F. & Jacobson, A. L. An overlooked hybrid Japanese knotweed (Polygonum cuspidatum x sachalinense; Polygonaceae) in North America. Rhodora 105, 143–152 (2003).

Bailey, J. P., Bímová, K. & Mandák, B. Asexual spread versus sexual reproduction and evolution in Japanese Knotweed s.l. sets the stage for the ‘battle of the clones’. Biol. Invasions. 11, 1189–1203 (2009).

Pang, J. et al. Green tea consumption and risk of cardiovascular and ischemic related diseases: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 202, 967–974 (2016).

Hadzik, J. et al. Oral wound healing potential of Polygoni Cuspidati Rhizoma et Radix Decoction—In Vitro Study. Pharmaceuticals 16, 267 (2023).

Nawrot-Hadzik, I. et al. In vitro gingival wound healing activity of extracts from Reynoutria japonica Houtt. Rhizomes. Pharmaceutics 13, 1764 (2021).

Ware, I. et al. Bioactive phenolic compounds from Peperomia obtusifolia. Molecules 27, 4363 (2022).

Lee, Y. A., Eun, J. C., Tanaka, T. & Yokozawa, T. Inhibitory activities of proanthocyanidins from Persimmon against oxidative stress and Digestive enzymes related to diabetes. J. Nutri. Sci. Vitaminol. 53, 287–292 (2007).

Rice-Evans, C. A., Miller, N. J. & Paganga, G. Structure-antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 20, 933–956 (1996).

Tabaripour, R., Sheidai, M., Talebi, S. M. & Noormohammadi, Z. Genetic divergence and speciation within Ziziphora capitata (Lamiaceae): Molecular and micromorphological evidences. Biodiversitas 19, 697–705 (2018).

Herpigny, B., Dassonville, N., Ghysels, P., Mahy, G. & Meerts, P. Variation of growth and functional traits of invasive knotweeds (Fallopia spp.) in Belgium. Plant. Ecol. 213, 419–430 (2012).

Bímová, K., Mandák, B. & Kašparová, I. How does Reynoutria invasion fit the various theories of invasibility? J. Veg. Sci. 15, 495–504 (2004).

Stalažs, A. The first findings of invasive Reynoutria × bohemica Chrtek & Chrtková (Polygonaceae) in Latvia. Bot. Lett. 169, 119–126 (2022).

Tippery, N. P., Olson, A. L. & Wendtlandt, J. L. Using the nuclear LEAFY gene to reconstruct phylogenetic relationships among invasive knotweed (Reynoutria, Polygonaceae) populations. Invasive Plant. Sci. Manag.. 14, 92–100 (2021).

Khalil, A. A. K. et al. Comparative inner morphological and chemical studies on reynoutria species in Korea. Plants 9, (2020).

Mandák, B. et al. Variation in DNA-ploidy levels of Reynoutria taxa in the Czech Republic. Ann. Bot. 92, 265–272 (2003).

Mandák, B., Bímová, K., Pyšek, P., Štěpánek, J. & Plačková, I. Isoenzyme diversity in Reynoutria (Polygonaceae) taxa: Escape from sterility by hybridization. Plant Syst. Evol. 253, 219–230 (2005).

Komuro, S., Endo, R., Shikata, K. & Kato, A. Genomic and chromosomal distribution patterns of various repeated DNA sequences in wheat revealed by a fluorescence in situ hybridization procedure. Genome 56, 131–137 (2013).

Hollingsworth, M. L. & Bailey, J. P. Hybridisation and clonal diversity in some introduced Fallopia species (Polygonaceae). Watsonia 23, 111–121 (2000).

VanWallendael, A., Alvarez, M. & Franks, S. J. Patterns of population genomic diversity in the invasive Japanese knotweed species complex. Am. J. Bot. 108, 857–868 (2021).

Pyšek, P. et al. Vegetative regeneration in invasive Reynoutria (Polygonaceae) taxa: The determinant of invasibility at the genotype level. Am. J. Bot. 90, 1487–1495 (2003).

Bailey, J. P., Child, L. E. & Conolly, A. P. A Survey of the Distribution of Fallopia x bohemica (Chrtek & Chrtkova) J. Bailey (Polygonaceae) in the British Isles. Watsonia 21, 187–198 (1996).

Bensa, M., Glavnik, V. & Vovk, I. Flavan-3-ols and proanthocyanidins in Japanese, bohemian and giant knotweed. Plants 10, 1–19 (2021).

Botstein, D., White, R. L., Skolnick, M. & Davis, R. W. Construction of a genetic linkage map in man using restriction fragment length polymorphisms. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 32, 314–331 (1980).

Roy, P., Sogir, S., Bin & Basak, T. On the polymorphism information content (PIC) – a practical application for the DNA sequencing data. Eur. J. Med. Health Res. 1, 21–29 (2023).

Serrote, C. M. L., Reiniger, L. R. S., Silva, K. B., dos Rabaiolli, S. M., Stefanel, C. M. & S. & Determining the polymorphism information content of a molecular marker. Gene 726, 144175 (2020).

Akçali Giachino, R. R. Investigation of the genetic variation of anise (Pimpinella anisum L.) using RAPD and ISSR markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 67, 763–780 (2020).

Tilwari, A. & Sharma, R. Random amplified polymorphic DNA and inter simple sequence repeat markers reveals genetic diversity between micro propagated, wild and field cultivated genotypes of Gloriosa superba: An endangered medicinal plant. Mol. Biol. Rep. 48, 2437–2452 (2021).

Ghobadi, G., Etminan, A., Mehrabi, A. M. & Shooshtari, L. Molecular diversity analysis in hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and two Aegilops species (Aegilops crassa and Aegilops cylindrica) using CBDP and SCoT markers. J. Genetic Eng. Biotechnol. 19, 56 (2021).

Avval, S. E. Assessing polymorphism information content (PIC) using SSR molecular markers on local species of Citrullus Colocynthis. Case Study: Iran, Sistan-Balouchestan Province. J. Mol. Biol. Res. 7, 42 (2017).

Buchanan, F. C. & Thue, T. D. Intrabreed polymorphic information content of microsatellites in cattle and sheep. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 78, 425–428 (1998).

Etminan, A. et al. Genetic relationships and diversity among wild Salvia accessions revealed by ISSR and SCoT markers. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 32, 610–617 (2018).

Amom, T. et al. Efficiency of RAPD, ISSR, iPBS, SCoT and phytochemical markers in the genetic relationship study of five native and economical important bamboos of North-East India. Phytochemistry 174, 112330 (2020).

Zhang, Y. Y., Zhang, D. Y. & Barret, S. C. H. Genetic uniformity characterizes the invasive spread of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes), a clonal aquatic plant. Mol. Ecol. 19, 1774–1786 (2010).

Havenga, M. et al. Low genetic diversity and strong geographic structure in introduced populations of the Eucalyptus foliar pathogen Teratosphaeria destructans. Plant. Pathol. 69, 1540–1550 (2020).

Keller, S. R. & Taylor, D. R. Genomic admixture increases fitness during a biological invasion. J. Evol. Biol. 23, 1720–1731 (2010).

Parepa, M., Fischer, M., Krebs, C. & Bossdorf, O. Hybridization increases invasive knotweed success. Evol. Appl. 7, 413–420 (2014).

Nei, M. & Li, W. H. Mathematical model for studying genetic variation in terms of restriction endonucleases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 76, 5269–5273 (1979).

Talebi, S. M. et al. Genetic structure and essential oil composition in wild populations of Salvia Multicaulis Vahl. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 96, 104269 (2021).

Pollux, B. J. A. et al. Reproductive strategy, clonal structure and genetic diversity in populations of the aquatic macrophyte Sparganium emersum in river systems. Mol. Ecol. 16, 313–325 (2007).

Binks, R. M., Millar, M. A. & Byrne, M. Contrasting patterns of clonality and fine-scale genetic structure in two rare sedges with differing geographic distributions. Heredity (Edinb). 115, 235–242 (2015).

R Core Team. R Core Team. : A language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing. (2023). R https://www.R-project.org/. R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2021 (2023).

Galili, T. Dendextend: An R package for visualizing, adjusting and comparing trees of hierarchical clustering. Bioinformatics 31, 3718–3720 (2015).

Golkar, P. & Nourbakhsh, V. Analysis of genetic diversity and population structure in Nigella sativa L. using agronomic traits and molecular markers (SRAP and SCoT). Ind. Crops Prod. 130, 170–178 (2019).

Jaccard, P. Sur La distribution Florale. Bull. de la. Société Vaudoise Des. Sci. Nat. 37, 223–270 (1908).

Kosman, E. & Leonard, K. J. Similarity coefficients for molecular markers in studies of genetic relationships between individuals for haploid, diploid, and polyploid species. Mol. Ecol. 14, 415–424 (2005).

Lê, S., Josse, J. & Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R package for multivariate analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 25, 1–18 (2008).

Prevost, A. & Wilkinson, M. J. A new system of comparing PCR primers applied to ISSR fingerprinting of potato cultivars. Theor. Appl. Genet. 98, 107–112 (1999).

Kamvar, Z. N., Tabima, J. F. & Grünwald, N. J. Poppr: An R package for genetic analysis of populations with clonal, partially clonal, and/or sexual reproduction. PeerJ 2, e281 (2014).

Jombart, T. Adegenet: A R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 24, 1403–1405 (2008).

Nei, M. Estimation of average heterozygosity and genetic distance from a small number of individuals. Genetics 89, 583–590 (1978).

DeGiorgio, M., Jankovic, I. & Rosenberg, N. A. Unbiased estimation of Gene Diversity in samples containing related individuals: Exact variance and arbitrary ploidy. Genetics 186, 1367–1387 (2010).

Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 27, 379–423 (1948).

Slatkin, M. & Barton, N. H. A comparison of three indirect methods for estimating average levels of Gene Flow. Evol. (N Y). 43, 1349–1368 (1989).

Pritchard, J. K., Stephens, M. & Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155, 945–959 (2000).

Evanno, G., Regnaut, S. & Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software structure: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 14, 2611–2620 (2005).

Li, Y., Liu, J. & StructureSelector: A web-based software to select and visualize the optimal number of clusters using multiple methods. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 18, 176–177 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Klemens Jakubowski, the curator of the Botanic Garden of Medicinal Plants at Wroclaw Medical University, for the formal identification of the plant material used in this study.We would like to thank Hanna Czapor-Irzabek for technical assistance in obtaining UHPLC-QTOF-MS data. Measurements were carried out in the Laboratory of Elemental Analysis and Structural Research at Wroclaw Medical University.

Funding

This research was funded by Wroclaw Medical University subvention, Grant Numbers: STM.D034.20.156, SUBK.D030.24.016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MS and INH conceptualized the study, conceived and organized the experiments. MS, AJD and INH performed the experiments. KK and MS performed the statistical analysis. BP and AB contributed to the data analysis. MS, AJD, INH and MB wrote the original manuscript. MB and AM supervised the project and reviewed and edited the final manuscript version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions