Abstract

Accurate diagnosis of both age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and inherited retinal diseases (IRD) with macular atrophy is important because treatments for both conditions are emerging. Phenotypical similarities between macular atrophy associated with AMD (geographic atrophy, GA) and IRD-associated atrophy exist, which can make accurate diagnosis challenging in clinical practice. Misdiagnosis may lead to inappropriate treatment strategies and missed opportunities for disease-specific interventions. A retrospective clinical review of medical records of people diagnosed with AMD between 1995 and 2023 from a large multidisciplinary private ophthalmic practice in Australia was undertaken to identify cases of patients diagnosed with geographic atrophy without drusen, which was then further assessed for potentially missed IRD with macular atrophy. Flagged cases were presented to experts in AMD and IRD to establish a most-likely diagnosis. Cases without consensus between graders were grouped into most-likely diagnosis by a third senior retinal clinician. Of the 1136 cases reviewed, the possible rate of misdiagnosis observed was 1.9%, with 1.0% representing potentially missed IRDs, most commonly pattern dystrophy (0.5%). A multi-modal approach, including clinical features and patient history, is important to limit the possibility of misdiagnosis of GA, and identify a subset of patients who might benefit from genetic testing prior to considering possible treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the developed world’s leading cause of irreversible vision loss for individuals over 551. The hallmark feature of AMD are drusen: extracellular material, including protein and lipid deposits that accumulate between the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and Bruch’s membrane, with the Beckman Classification of AMD requiring drusen deposits to be > 63 μm diameter for a diagnosis1. Reticular pseudodrusen (RPD) accumulate in the subretinal space2 (also known as subretinal drusenoid deposits), and can occur in multiple retinal diseases and also in individuals without other retinal deposits3. They are strongly associated with advanced AMD, although, unlike sub-retinal pigment epithelium drusen, they are not diagnostic. Whilst genetic testing can provide a polygenic risk score for AMD4, it currently is rarely used in the diagnosis of AMD and its use is limited by real-world availability and cost.

There are two forms of late-stage AMD: geographic atrophy, (GA, dry), and neovascular AMD, (wet). Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapies are currently available for neovascular AMD and have shown reduced rates of vision loss over the past decade5. The pathogenesis of geographic atrophy (GA) is multifactorial and is thought to involve several pathways with oxidative damage and chronic inflammation thought to be two processes involved, leading to loss of photoreceptors, RPE and choriocapillaris. GA is traditionally defined as a lesion seen on colour fundus photography with a sharply defined pale region with choroidal vessels in its base6. On OCT, GA is seen as a region of hypertransmission below the retina with attenuation or disruption of the RPE and loss of the photoreceptor bands7. Complement-based therapies for GA, including pegcetacoplan8 and avacincaptad pegol9,10 have recently been approved in the USA and slow progression of GA lesion growth.

Inherited retinal diseases (IRDs) are a group of heterogeneous disorders caused typically by a single gene defect inherited in a Mendelian manner, acting in or on photoreceptors, commonly via RPE abnormalities. More than 350 causative genes or loci are recognised. The macula only IRD phenotype (macular dystrophy) constitutes approximately 30% of all IRD cases11,12. Although distinct in disease process compared to AMD, IRDs may present with similar clinical phenotype (“phenocopy”). Some develop chorioretinal atrophy, with similar appearance to GA, the subject of this study. Some IRD phenocopies of GA include drusen (reviewed by Saskens13) including EFEMP1-associated autosomal dominant drusen14, and CFH loss of function15 and heterozygous variants. Some AMD phenocopies develop RPD including Sorsby fundus dystrophy16, autosomal recessive bestrophinopathy, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, late-onset retinal degeneration associated with mutation in C1QTNF517, and possibly Extensive Macular Atrophy with Pseudodrusen-like appearance18. Systemic genetic and acquired complement disorders such as C3 glomerulonephropathy can be another phenocopy of drusen in AMD19. Abetalipoproteinaemia has been described as a cause of isolated macular atrophy simulating late GA20. Currently clinical trials of ocular gene therapy for more than 20 types of IRD are underway21,22,23. The onset of IRDs is often within the first three decades, in contrast to AMD; however, distinguishing atrophy in IRDs from GA secondary to AMD, particularly in patients presenting at an older age, can be clinically challenging13,24.

Developments in multimodal imaging including Ocular Coherence Tomography (OCT) scanning, fundus autofluorescence (FAF), and near-infrared imaging (NIR), have improved our ability to accurately diagnose retinal diseases. Whilst some retinal conditions can be diagnosed primarily based on clinical history and retinal signs, shared features between multiple disease processes require nuanced interpretation for accurate diagnosis. This is particularly true for macular diseases, including AMD and late-onset macular dystrophies with atrophy. Whilst each disease entity has different underlying pathophysiological processes and typical features many share a common end stage phenotype. The challenges of clinically distinguishing them has been recognized in the literature13,24. Without widely-available genetic testing to screen cases for some of the IRDs, clinicians need to be alert to mimicking conditions and understand which type of imaging can be used to assist with accurate diagnosis of these cases.

With treatment options becoming available for both GA and IRD and diagnosis complicated by the phenotypical similarities shared between the two diseases, ensuring patients receive an accurate diagnosis and therefore treatment, is more important than ever as this will inform the possible treatment modalities. Even though research studies have evaluated the prevalence of some IRD genes in AMD cohorts24, no studies have looked at this in a real-world clinical setting. We sought to determine the possible frequency of misdiagnosis when considering people with a diagnosis of GA secondary to AMD by performing an audit of real-world clinical records from a large ophthalmology practice in Australia.

Methods

Participants

Participants were adult patients with a diagnosis of AMD (with or without choroidal neovascularisation) in at least one eye, and minimum one OCT scan in their retrospective medical record.

To identify eligible participants, a retrospective medical record assessment was undertaken of patient records at Eye Surgery Associates (ESA), a large multidisciplinary ophthalmic practice in Melbourne Australia for patients attending between 1 January 1995 and 5 May 2023. Records of fourteen participating ophthalmologists (of the current eighteen ophthalmologists) were reviewed; eight had medical retina specialist practices, and six had other specialties. All potential participants had undergone complete medical and ophthalmic history and complete eye examination, including visual acuity assessment (ETDRS chart), intraocular pressure measurement (Tonopen, Reichert, New York, USA; or iCare, Icare Finland), evaluation of pupils, slit lamp biomicroscopy and dilated indirect ophthalmoscopy. Approximately 90% of potential participants had undergone OCT scanning of the atrophic lesion(s) (Stratus (OCT3) and Cirrus, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany; Spectralis HRA + OCT, Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) including scout en-face NIR retinal images. OCT scan pattern was variable including single line scans and high-density scanning. Approximately 20% had colour fundus photographs (CFP; Topcon TRC-50EX, Tokyo, Japan; 35o). A minority (< 15%) had FAF (488 nm) imaging (Spectralis HRA + OCT, Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany). Following standard clinical practice in Australia, no patients clinically diagnosed with AMD had genetic testing to exclude IRD or confirm AMD risk alleles.

Data screening

Record screening and data extraction was undertaken following the published study protocol25. In brief, the patient electronic database of 115,127 individual patient records (Best Practice, Bundaberg, Australia, bpsoftware.net) was searched using the terms “geographic atrophy,” “GA,” “macular degeneration,” “AMD” and “ARMD” on 5 May 2023.

Initial data extraction was performed by a single medical student reviewer (DM) after training by a senior medical retinal ophthalmologist (HGM) using a panel of standard images (Supplementary Fig. 1). The first 120 records screened were supervised by HGM and co-graded. Subsequent records were reviewed by DM with multiple opportunities throughout the screening process to clarify any complex cases with HGM.

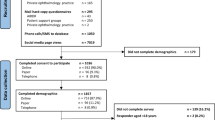

Records were initially screened (Fig. 1) to exclude patients with confounding medical and ocular medical history potentially resulting in macular atrophy (such as prolonged oral steroid exposure, retinotoxic medications (e.g., hydroxychloroquine, pentosan polysulfate), ocular trauma, retinal vein occlusion, and other major retinal pathologies; macular laser (other than thermal laser or photodynamic therapy for choroidal neovascularization); and myopia > 6D (including prior to cataract surgery)25. We included images from both eyes if they were available, but imaging available on only one eye was not an exclusion factor. Records without at least one OCT scan through the atrophic lesion(s) were excluded.

The second step of the screening process identified these patient records with macular atrophy without sub-RPE drusen. Sufficient images of all available modalities were reviewed during this screening stage to determine the presence of atrophy and presence or absence of sub-RPE drusen at any timepoint. Macular atrophy was diagnosed on OCT scanning using criteria of one or more regions of hypertransmission, with attenuation or disruption of the RPE and the overlying photoreceptors26. Atrophy was diagnosed on FAF as a well-defined area of lack of lipofuscin autofluorescence (hypoautofluorescence). Atrophy was diagnosed on colour fundus photographs as a sharply defined area of dropout of RPE, exposing choroidal vessels6. Lesions were not measured, and artificial intelligence was not used in their assessment.

Cases with atrophy and drusen were considered a priori to be AMD and were not further considered. RPD were not an exclusion factor. Screening identified participants potentially misdiagnosed with AMD, whose records included macular atrophy without sub-RPE drusen at any stage to be subject to expert review. To assess inter-observer reliability for detecting atrophy and drusen, 100 randomly selected cases were reviewed by DM and HGM independently.

Expert Review

Screened records were separately reviewed by senior retinal sub-specialist ophthalmic graders with research expertise in AMD (RHG) and IRD (TLE). At this stage all available images in all modalities were reviewed. For each case, the grader reviewed the confidence of AMD diagnosis based on each available imaging modality (OCT, FAF, CFP, and NIR images), and then graded the most likely diagnosis, being AMD, IRD or another retinal condition marked by atrophic maculopathy. Graders made individual clinical diagnoses using the following guidelines. AMD with RPD phenotype demonstrated macular atrophy with RPD visible on OCT scanning. Size of drusen and pigmentation were not considered27. IRD demonstrated macular atrophy, hyperautofluorescent flecks at the level of the RPE on short-wave FAF and possibly nasal distribution of retinal changes28. Non-specific atrophy was diagnosed after excluding all other clinically evident causes of macular atrophy. Graders were asked to assess the case, firstly based on multimodal images only (with no family history or age of onset), then information on patient age was then given after a decision was made, and a final diagnosis was then decided. Artificial intelligence was not used in grading decisions.

Following independent assessment, patient files were classified as having reached consensus or not having reached consensus for the most likely diagnosis. For patients without an agreed diagnosis between experts a third medical retinal specialist (HGM, senior author, specialist in both medical retina and IRD) became the final arbitrator and determined their most likely diagnosis which was used in the analysis.

Data management and privacy

De-identified data from study screening was managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) electronic data capture tools hosted at The University of Melbourne. REDCap is a secure, web-based software platform that provides audit trails for tracking data capture and manipulation, and export procedures29. Access to medical records and study data was password-restricted to the members of the study team.

Data analysis

De-identified data was imported into Excel (Microsoft WA, USA) for statistical analysis. Differences in proportions were examined using the Fisher’s exact test. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Internal reliability for detecting drusen was assessed using Cohen’s kappa30.

Ethics

Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) approval was granted by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists Human Research Ethics Committee on 31st March 2023. All participants in the retrospective audit provided written informed consent to have their records audited for research purposes. All ophthalmologists whose patient files were audited agreed to participate in the study. All patients whose deidentified images are included in this publication provided written consent. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Screening

A total of 6137 patients were identified using keyword search terms (Fig. 1). The majority of cases were managed by retinal subspecialists (n = 4289, 75.2%). During screening of records, the mean number of visits assessed was 3.0 per patient record (range 1–55). Inter-rater reliability between the screener and the senior author was moderate agreement (89% agreement, k = 0.69) in detecting the presence or absence of drusen, and strong agreement in the detection of atrophy (91% agreement, k = 0.82), for the 100 images randomly selected to be graded independently. To further improve the accuracy of drusen and atrophy detection, cases deemed unclear or ambiguous by the first author during the initial grading process underwent co-review by the senior consultant ophthalmologist (HGM). This collaborative review process facilitated discussion and resolution of any uncertain cases.

Of 1136 cases of atrophy identified, 31 did not have conventional drusen present in any point, including the first visits, in the clinical record resulting in an overall potential misdiagnosis rate of 2.8%.

Of these 31 cases, 27 were managed by retinal subspecialists and four patients were managed by ophthalmologists with other specialities. At this stage of screening, the rate of patients with atrophy potentially misdiagnosed as AMD due to the lack of sub-RPE drusen was 3.4% (range 1.1–6.8%) for retinal specialists and 4.2% (range 1.7–13.3%) for general and non-retinal specialist ophthalmologists, which was not significantly different between groups (p = 0.99) or between individual doctors.

Data analysis flow in a retrospective audit of records of people diagnosed with age-related macular degeneration. †Drusen based on the Beckman Initiative for Macular Research Classification Committee standards, and defined as pale yellow deposits which on OCT are beneath the retinal pigmented epithelium > 63 mm)1. AMD, age-related macular degeneration; ESA, Eye Surgery Associates; GA, geographic atrophy; IRD, inherited retinal disease; OCT, optical coherence tomography; RPD, reticular pseudodrusen (also known as subretinal drusenoid deposits).

Expert Review

Of the 31 cases of macular atrophy that underwent expert review, consensus was reached in 16 cases (16/31, 52%, Supplementary Table 1). The group with expert consensus diagnosis comprised 62.5% (10/16) women, and had a mean age of 81.6 years (range 64–97 years). Agreed diagnoses were atrophy with RPD secondary to AMD (7), IRD (5), and non-specific atrophy (4). Examples of participants with agreed diagnoses are displayed in Fig. 2.

Examples of patients with expert consensus identified in an audit of 1136 cases of macular atrophy. Case 1. Expert consensus diagnosis IRD based on changes nasal to the optic disc. Colour fundus photographs of the (A) right and (B) left eyes of a white male aged 52 years showing drusen; photographs of the (C) right and (D) left eyes five years later showing focal atrophy in the left eye; FAF of the (E) right and (F) left eyes seven years following this showing extensive foci of hypoautofluorescence nasal and temporal to the optic disc in both eyes with peripapillary atrophy. Case 8. Non-specific macular atrophy left eye. Red free photographs of the (G) right and (H) left eye of a 75-year-old white male; Fluorescein angiography of the (I) right and (J) left eyes and OCT scans of the K) right and L) left eye three years later. Right eye has incidental branch retinal vein occlusion with cystoid macular oedema, and non-specific atrophy in the left eye. No fundus photographs were available for this patient.

The cases in which no expert consensus was reached (15/31, 48%) comprised 47% (7/15) women, and had mean age of 79.7 years (range 61–93 years). The groups with and without expert consensus were not statistically different with respect to age and gender. Cases were grouped by the senior author, including suggested putative diagnoses of pattern macular dystrophy (6), non-specific atrophy (4), myopic macular atrophy (3) and atrophy with reticular pseudodrusen secondary to AMD (2). Representative examples of cases where no expert consensus was reached are shown in Fig. 3.

Examples of patients without expert consensus suspected of having other causes of macular atrophy identified in an audit of 1136 cases of macular atrophy Case 21. Classification diagnosis pattern macular dystrophy. Colour fundus photograph of the (A) right and (B) left eyes of a 63 year old white female showing foci of atrophy in the right eye and an incidental left choroidal naevus; OCT scanning of the (C) right and (D) left eyes showing a focus of atrophy in the right eye without drusen; infrared photography of the (E) right and (F) left eyes two years later, at age 65, showing two foci of atrophy with radiating pale lesions in the right eye; FAF of the (G) right and (H) left eyes demonstrating foci of hypoautofluorescence in the right eye. Case 29. Myopic macular atrophy. Infrared images of the (I) right and (J) left eyes; OCT scans of the K) right and L) left eyes of an 87-year-old white male. Images interpreted as showing bilateral peripapillary atrophy, staphyloma and foci of atrophy associated with unrecognized myopic macular changes. Spherical equivalent was R) eye − 1.12D and L) eye − 0.62 pre-cataract surgery.

Final calculations

Recalculating after expert review and senior author review, and reclassifying AMD with RPD as correctly diagnosed, the possible misdiagnosis rate was 1.9% (22/1136) of participants diagnosed previously with AMD with GA (Table 1). Expert graders were consistent with each other in 52% (16/31) of cases. Overall, the potential misdiagnoses were IRD/pattern dystrophy 0.97% (11/1136), non-specific atrophy 0.70% (8/1136) and myopic macular atrophy 0.26 (3/1136).

Features which aided clinical judgement in making a most-likely diagnosis

Patient history and age

Particularly for cases that were difficult to judge based on phenotypical features alone, patient age formed an important part of the clinical picture and approaching diagnosis for the expert graders. Macular appearance for Case 16 (data not shown) was suggestive of an AMD-like pattern of atrophy according to both experts. However, the patient was 45 years old at the time of imaging, with both graders arriving in agreement of a consensus diagnosis of IRD given the patient’s age.

Of the six flagged records below the age of 70-years-old, three had a consensus diagnosis of IRD. The other three cases did not have a consensus diagnosis, and one case was categorized by the expert committee as non-specific atrophy whilst the remaining two are suspected to have a pattern dystrophy. Hence a younger age (< 70yo), should be considered an important factor in raising the possibility of non-AMD atrophy,

Other important clinical information that both graders noted as clinical history considerations included other causes of retinal atrophy, including infectious causes such as rubella and syphilis, history suggestive of mitochondrial disease such as Maternally Inherited Deafness and Diabetes and history of myopia.

Symmetry

Symmetry, or the absence of, in the phenotype of each eye was a key clinical finding used by both graders to assist in identifying a most likely diagnosis for each case’s maculopathy. Highly symmetrical changes were identified as more suggestive of a dystrophy-driven cause, as opposed to AMD, although recognizing that AMD is usually a bilateral disease and often GA is present in both eyes.

Although there was no clear consensus for Case 22 (data not shown), a 78-year-old male, the absence of macular disease in one eye deterred both experts from a diagnosis of IRD. In Case 5 (data not shown), imaging was available for one eye only, making it challenging for both graders to differentiate between the two diseases, and both experts acknowledged that this case was unclear without bilateral assessment of the retinae.

However, for Case 21 (Fig. 2), a 73-year-old female, absence of symmetry deterred the IRD expert from making a diagnosis of IRD, whilst the AMD expert considered this to be phenotypically consistent with right-eye only reticular pattern dystrophy. Final arbitrated diagnosis was pattern dystrophy.

Multimodal imaging modalities

While OCT was determined as the modality most helpful in assessing with screening for drusen, FAF was very helpful in assessing the likely cause of the atrophy but was not always available. Of 31 cases with atrophy without drusen assessed, 9 had FAF. Most cases with FAF (n = 7, 78%) were able to reach expert consensus, whereas for the cases without FAF only 9/22 (41%) cases reached consensus based on available information. This highlights the importance of taking FAF images in cases of atrophy to help confirm its underlying cause.

Discussion

In the context of emerging treatments for both GA and IRD, this retrospective clinical study of a private, tertiary ophthalmology clinic in Australia has identified a low potential rate of misdiagnosis rate of 1.9% of patients previously diagnosed with AMD with GA. Our finding was based on review of clinical imaging of patients with macular atrophy and without obvious drusen present. Genetic testing was not undertaken. Nonetheless, these findings highlight the challenges of distinguishing between macular diseases based solely on phenotypes in a real-world clinical setting, especially in situations where genetic testing might not be readily accessible. Our low potential misdiagnosis rate might possibly be even lower as we may have inadvertently included patients correctly diagnosed with AMD, who attended our clinics after all drusen had regressed.

The low potential misdiagnosis rate for IRD compares well with other ophthalmic conditions. Borrelli et al. reported a 15.4% misdiagnosis rate of patients with pachychoroid disease and exudative macular neovascularisation amongst a population of 104 Caucasians who were diagnosed with neovascular AMD31. Dias et al. reported in an academic setting a misdiagnosis rate of 25% of eyes with neuroophthalmological disorders to be glaucoma32.

Overall diagnostic error rates in real-world medical practice are not known, but a commonly cited estimate based on expert opinion is that 10–15% of all diagnoses are incorrect; rates measured in studies using chart reviews are often an order of magnitude lower33. Our rate of 1.9% is comparable to other retrospective reviews of hospital admissions (0.4%)34 and hospital outpatients (5.1%)35.

We found no statistical difference in diagnostic accuracy between retinal and non-retinal ophthalmologists. This most likely reflects low numbers. Studies of diagnostic accuracy in ocular melanoma36 and glaucoma37 have demonstrated that specialists in the field have higher diagnostic accuracy. Artificial intelligence may further improve diagnostic accuracy in ophthalmology38.

Non consensus in diagnosis between experts in AMD and IRD in 52% of cases filtered for expert review demonstrates the difficulty of clinical diagnosis in some patients without genetic testing, even for the most skilled retinal specialists. Noting this difficulty, the commonest potential missed diagnoses were IRD and pattern macular dystrophy, non-specific macular atrophy and possible myopic macular atrophy. Our rate is comparable to Kersten et al. who performed genetic testing and found pathogenic heterozygous variants causal for IRD in 1.4% cases of clinically diagnosed AMD24.

In the future it is hoped that making genetic testing available for selected patients could serve as a valuable tool for screening for potential IRDs. Genetic sequencing technology has progressed significantly, including development of effective sequencing strategies for genetic diagnosis of macular dystrophies39. Despite progress, IRD genetic screening remains unsustainable to offer to patients routinely in suspected AMD. Additionally, studies screening AMD patients for macular dystrophy-associated genes have demonstrated that there is a degree of genetic overlap between these two cohorts24,40. Patients may also have both an IRD and AMD. Therefore, even with genetic testing targeted for selected patients, in many cases diagnosis will be based on clinical judgement, carrying a low inherent risk of misdiagnosis.

Selected cases (Figs. 2 and 3) highlight further learnings in making or revisiting a clinical diagnosis. AMD is by definition a condition of people 50 years and older; we included people < 50 years of age in the audit to capture clinical diagnoses of “early onset drusen.” Case 16 illustrates the role of age in making a clinical diagnosis. 60% of patients (3/5) with a consensus diagnosis of IRD were below the age of 70 (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). However, older age did not preclude individuals from being suspected of having an IRD, with the remaining two IRD cases aged 93-years-old. An opportunity to conduct a thorough history may have elucidated an early onset of a strong family history of loss of vision, but that was not available in this setting. This demonstrates in clinical practice that whilst younger age is more suggestive of a macular dystrophy, the possibility of IRD in older patients should not be ruled out. Case 8 illustrates unilateral signs make confident diagnosis of an IRD more challenging given the importance of symmetric bilateral signs in this condition.

Other learnings for eyecare professionals are to be mindful of the RPD-only AMD phenotype. These patients were included in landmark trials of complement therapeutics in GA8,9,10, so complement based treatments are not inappropriate. Additionally, Case 1 illustrates confirmation bias, where the original diagnosis of AMD was not changed over the subsequent years despite new FAF data emerging suggestive of an IRD.

Our audit identified patients with myopic maculopathy and non-specific forms of atrophy. Myopic atrophy was diagnosed despite filtering of records in which myopia > 6D was identified (Fig. 1) showing that past myopia may not be included in medical records of people who have had cataract surgery, and confirming that lower grades of myopia in rare cases can be associated with macular atrophy41. The pathogenesis of myopic and non-specific forms of atrophy are not recognized to include complement dysfunction and there is no current evidence to support the use of complement-based therapeutics in their treatment.

Different information was provided by multimodal imaging to aid in diagnosis. Consistent with clinical practice OCT was subjectively determined to be the modality that most often assisted in the identification and initial characterisation of drusen26,42 and distinguishing them from flecks. FAF was determined to be the modality used most frequently by experts to distinguish between AMD and IRD. In addition to the use of these technologies we recommend the following as important differentiators between the various atrophic maculopathies: age of macular atrophy onset, family history of central vision loss, lifestyle factors affecting risk of AMD (predominantly cigarette smoking), symmetry of fundus findings, involvement nasal to the optic disc (e.g. Case 1) and accurate distinction between drusen and retinal flecks. Using this approach, targeted genetic testing may then be recommended for cases where it is difficult to determine the underlying aetiology of the atrophy. Future work by our team will focus on the efficiency and efficacy of genetic testing in this situation. Note that there will be an inherent rate of potential clinical misdiagnosis despite best efforts due to pathologies mimicking AMD, but the goal is for this to be minimized.

Treatments are emerging for IRDs.21,22,23,43,44,45,46,47,48,49 Genetic diagnosis is essential for gene-specific treatments, and desirable for gene-agnostic treatments. Typical of real-world AMD practice, our patients with AMD diagnosis did not have genetic testing to screen for IRDs or identify at risk AMD alleles. Our results identify a subset of < 1% people with macular atrophy due to possible IRD who may have been offered complement-based therapeutics, and who may not be offered the opportunity to enter clinical trials for treatment appropriate for their condition. No data is available on treating patients with macular atrophy secondary to IRD with pegcetacoplan or avacincaptad pegol as these patients were not intended to be included in the pivotal clinical trials8,9,10. However, treatment with complement-based inhibition is unlikely to be effective given that complement pathway dysfunction has not been recognised to date as one of the mechanisms of development of macular atrophy.

A key strength to the study was analysis of a large data set collected in a real-world setting, capturing over 5000 cases presenting over almost thirty years. Long-term follow-up for many patients assisted in identifying patients who had typical drusen changes prior to the onset of atrophy. As a real-world data set, despite being from a single practice, the assessment of multiple patients from fourteen different ophthalmologists increases the external validation of the study.

A key limitation was having the first screening performed by a medical student making it possible that flecks may have been misinterpreted as drusen. We attempted to reduce this by training using standardised images (Supplementary Fig. 1) and implementing a collaborative review process with a senior retinal consultant. While independent review and consensus by multiple reviewers may have improved internal reliability, resource constraints limited this approach. The use of deep learning techniques for grading may prove valuable for similar screening approaches in the future. Another key limitation was auditing records with only the keywords ‘geographic atrophy,” “GA,” “macular degeneration,” “AMD” and “ARMD”. This excluded other words that may have been used to describe the atrophic change. This decision was made in the context of emerging complement-based treatments for GA, as we aimed to identify the possible misdiagnosis of IRDs as GA secondary to AMD, excluding other diagnoses of atrophy to make the record numbers manageable. Another limitation was only considering typical drusen, using the Beckman classification, in defining AMD1. We acknowledge other phenotypes in AMD are becoming understood, particularly RPD27. Although focussed on typical drusen, our audit separately identified patients with the RPD phenotype following expert review.

As a clinical practice audit from visits over a timespan of many years and many different clinicians, the data set relied on clinical records and therefore was incomplete in many instances, including lacking imaging from both eyes for some patients. There was variation in the available imaging modalities over the 28-year period of review, demonstrating evolving and non-uniform available imaging technologies in the real-world. Only 15% of patients had FAF imaging, which is critical for differentiating GA from IRD, reflecting relatively late introduction of FAF into routine retinal practice in Australia. Some patients had older OCT imaging, which has been superseded; some patients only had one line scan OCT performed, giving a risk of graders missing drusen that would have been identifiable with more thorough imaging. We acknowledge that this may introduce information bias. A recent study has demonstrated that high-resolution OCT (HR-OCT) improves the accuracy of detection, classification and agreement between reviewers of atrophic AMD lesions compared to standard resolution OCT50. This suggests that there may be patients with atrophic lesions which could not be fully appreciated or quantified on available imaging modalities; ultimately detection of these lesions will improve as the availability of this technology increases. The lack of uniform imaging of patients, may have introduced bias with more complete investigation and imaging having led to a higher rate of diagnosis of IRD.

Additional aspects to consider regarding the estimated clinical misdiagnosis rate is that patients may have presented with GA after regression of drusen, so incomplete records may have included patients as potentially misdiagnosed when drusen had been present and subsequently regressed. Overall, the testing algorithm may have resulted in an overestimate of misdiagnosis due to missed drusen. On the other hand, the decision to exclude all drusen associated with atrophy as possible AMD a priori may have underestimated the misdiagnosis rate. Some IRDs can present with drusen-like deposits and can appear concurrently with atrophy (for example, Sorsby fundus dystrophy). Although these phenotypes are rare, the true rate of misdiagnosis may be higher if we had included cases with drusen in our assessment. For the flagged cases, specific subgroups (e.g., pattern dystrophies) were identified based on retinal phenotypes. However, we could not compare subgroups or draw confirmed conclusions about these diagnoses without genetic information, particularly for the cases lacking agreement between specialist graders. These findings reflect difficulty in making accurate diagnosis for rare macular dystrophies without access to genetic testing. Even though the lack of genetic testing in our audit limits the accuracy of final diagnoses, these findings nonetheless reflect real-world resource constraints limiting genetic testing access to a minority of patients. The dataset of 31 cases was not large enough for statistical analysis by year of examination, ophthalmologist seen and availability of FAF images.

Conclusion

Although the rate of potential misdiagnosis in this retrospective clinical audit, based on multimodal imaging review without genetic confirmation, was found to be low (1.9%), it is important for clinicians to be cognizant of the potential opportunity for AMD-mimicking dystrophies (AMD “phenocopies”) and other atrophic macular pathologies to be incorrectly diagnosed. This incorrect diagnosis could lead to inappropriate treatment. Poor correlation between specialist graders highlights the difficulty of clinical diagnosis, and the role of genetic testing in assisting with diagnosis. In the first instance clinicians should employ a multi-modal imaging approach to diagnose causes of macular atrophy and show a level of heightened awareness in cases of atrophy in people under 70 years of age. Final diagnosis of IRD amongst patients with macular atrophy is likely to require genetic confirmation. Further prospective studies differentiating forms of macular atrophy, with genetic testing, are required.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [H.G.M.], upon reasonable request.

References

Ferris, F. L. 3rd et al. Clinical classification of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 120, 844–851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.10.036 (2013).

Khan, K. N. et al. Differentiating drusen: Drusen and drusen-like appearances associated with ageing, age-related macular degeneration, inherited eye disease and other pathological processes. Prog Retin Eye Res. 53, 70–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2016.04.008 (2016).

Wightman, A. J. & Guymer, R. H. Reticular pseudodrusen: current understanding. Clin. Exp. Optom. 102, 455–462. https://doi.org/10.1111/cxo.12842 (2019).

Fritsche, L. G. et al. A large genome-wide association study of age-related macular degeneration highlights contributions of rare and common variants. Nat. Genet. 48, 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3448 (2016).

Solomon, S. D., Lindsley, K., Vedula, S. S., Krzystolik, M. G. & Hawkins, B. S. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 3, CD005139. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005139.pub4 (2019).

Klein, R. et al. The Wisconsin age-related maculopathy grading system. Ophthalmology 98, 1128–1134. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32186-9 (1991).

Guymer, R. H. & Campbell, T. G. Age-related macular degeneration. Lancet 401, 1459–1472. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02609-5 (2023).

Liao, D. S. et al. Complement C3 inhibitor Pegcetacoplan for Geographic Atrophy secondary to age-related Macular Degeneration: a randomized phase 2 trial. Ophthalmology 127, 186–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.07.011 (2020).

Khanani, A. M. et al. Efficacy and safety of avacincaptad pegol in patients with geographic atrophy (GATHER2): 12-month results from a randomised, double-masked, phase 3 trial. Lancet 402, 1449–1458. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01583-0 (2023).

Jaffe, G. J. et al. C5 inhibitor Avacincaptad Pegol for Geographic Atrophy due to age-related Macular Degeneration: a Randomized Pivotal Phase 2/3 Trial. Ophthalmology 128, 576–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.08.027 (2021).

Stone, E. M. et al. Clinically focused Molecular Investigation of 1000 consecutive families with inherited retinal disease. Ophthalmology 124, 1314–1331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.04.008 (2017).

Coco-Martin, R. M., Diego-Alonso, M., Orduz-Montana, W. A., Sanabria, M. R. & Sanchez-Tocino, H. Descriptive study of a cohort of 488 patients with inherited retinal dystrophies. Clin. Ophthalmol. 15, 1075–1084. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S293381 (2021).

Saksens, N. T. et al. Macular dystrophies mimicking age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 39, 23–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2013.11.001 (2014).

de Guimaraes, T. A. C. et al. A long-term Retrospective Natural History Study of EFEMP1-Associated autosomal Dominant Drusen. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 65, 31. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.65.6.31 (2024).

Taylor, R. L. et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the CFH Gene affecting alternatively encoded factor H-like 1 protein cause Dominant early-Onset Macular Drusen. Ophthalmology 126, 1410–1421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.03.013 (2019).

Gliem, M. et al. Reticular pseudodrusen in Sorsby Fundus dystrophy. Ophthalmology 122, 1555–1562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.04.035 (2015).

Cukras, C. et al. Longitudinal structural changes in late-onset retinal degeneration. Retina 36, 2348–2356. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000001113 (2016).

Antropoli, A. et al. Extensive Macular Atrophy with Pseudodrusen-like appearance (EMAP): progression kinetics and late-stage findings. Ophthalmology https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2024.04.001 (2024).

Savige, J. et al. Retinal disease in the C3 glomerulopathies and the risk of impaired vision. Ophthalmic Genet. 37, 369–376. https://doi.org/10.3109/13816810.2015.1101777 (2016).

Alshareef, R. A., Bansal, A. S., Chiang, A. & Kaiser, R. S. Macular atrophy in a case of abetalipoproteinemia as only ocular clinical feature. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 50, e43–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjo.2014.12.016 (2015).

Garafalo, A. V. et al. Progress in treating inherited retinal diseases: early subretinal gene therapy clinical trials and candidates for future initiatives. Prog Retin Eye Res. 77, 100827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2019.100827 (2020).

Fuller-Carter, P. I., Basiri, H., Harvey, A. R. & Carvalho, L. S. Focused update on AAV-Based gene therapy clinical trials for inherited retinal degeneration. BioDrugs 34, 763–781. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-020-00453-8 (2020).

Brar, A. S. et al. Gene Therapy for Inherited Retinal Diseases: from Laboratory Bench to Patient Bedside and Beyond. Ophthalmol. Ther. 13, 21–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-023-00862-2 (2024).

Kersten, E. et al. Genetic screening for macular dystrophies in patients clinically diagnosed with dry age-related macular degeneration. Clin. Genet. 94, 569–574. https://doi.org/10.1111/cge.13447 (2018).

Britten-Jones, A. C. et al. Characterising the diagnosis of genetic maculopathies in a real-world private tertiary retinal practice in Australia: protocol for a retrospective clinical audit. Ann. Med. 55, 2250538. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2023.2250538 (2023).

Sadda, S. R. et al. Consensus Definition for Atrophy Associated with Age-Related Macular Degeneration on OCT: Classification of Atrophy Report 3. Ophthalmology 125, 537–548 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.09.028

Wu, Z., Fletcher, E. L., Kumar, H., Greferath, U. & Guymer, R. H. Reticular pseudodrusen: a critical phenotype in age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 88, 101017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2021.101017 (2022).

Pichi, F., Abboud, E. B., Ghazi, N. G. & Khan, A. O. Fundus autofluorescence imaging in hereditary retinal diseases. Acta Ophthalmol. 96, e549–e561. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.13602 (2018).

Harris, P. A. et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inf. 42, 377–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 (2009).

McHugh, M. L. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. (Zagreb). 22, 276–282 (2012).

Borrelli, E. et al. Rate of misdiagnosis and clinical usefulness of the correct diagnosis in exudative neovascular maculopathy secondary to AMD versus pachychoroid disease. Sci. Rep. 10, 20344. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77566-1 (2020).

Dias, D. T., Ushida, M., Battistella, R., Dorairaj, S. & Prata, T. S. Neurophthalmological conditions mimicking glaucomatous optic neuropathy: analysis of the most common causes of misdiagnosis. BMC Ophthalmol. 17, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-016-0395-x (2017).

Newman-Toker, D. E. et al. Rate of diagnostic errors and serious misdiagnosis-related harms for major vascular events, infections, and cancers: toward a national incidence estimate using the Big Three. Diagnosis (Berl). 8, 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0104 (2021).

Zwaan, L. et al. Patient record review of the incidence, consequences, and causes of diagnostic adverse events. Arch. Intern. Med. 170, 1015–1021. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2010.146 (2010).

Singh, H., Meyer, A. N. & Thomas, E. J. The frequency of diagnostic errors in outpatient care: estimations from three large observational studies involving US adult populations. BMJ Qual. Saf. 23, 727–731. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002627 (2014).

Khan, J. & Damato, B. E. Accuracy of choroidal melanoma diagnosis by general ophthalmologists: a prospective study. Eye (Lond). 21, 595–597. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702276 (2007).

Zhu, W. et al. Agreement of Optic nerve head evaluation of primary Open-Angle Glaucoma between General ophthalmologists and Glaucoma specialists. Risk Manag Healthc. Policy. 14, 1815–1822. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S307527 (2021).

Thirunavukarasu, A. J. et al. Large language models approach expert-level clinical knowledge and reasoning in ophthalmology: a head-to-head cross-sectional study. PLOS Digit. Health. 3, e0000341. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pdig.0000341 (2024).

Britten-Jones, A. C. et al. The Diagnostic yield of Next Generation sequencing in inherited retinal diseases: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 249, 57–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2022.12.027 (2023).

Hitti-Malin, R. J. et al. Towards uncovering the role of Incomplete Penetrance in Maculopathies through sequencing of 105 Disease-Associated genes. Biomolecules 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14030367 (2024).

Haarman, A. E. G. et al. The complications of myopia: a review and Meta-analysis. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 61, 49. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.61.4.49 (2020).

Oncel, D. et al. Drusen morphometrics on optical coherence tomography in eyes with age-related macular degeneration and normal aging. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 261, 2525–2533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-023-06088-z (2023).

Britten-Jones, A. C. et al. The safety and efficacy of gene therapy treatment for monogenic retinal and optic nerve diseases: a systematic review. Genet. Med. 24, 521–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gim.2021.10.013 (2021).

Administration., U. S. F. a. D. FDA Approves Novel gene Therapy to Treat Patients with a rare form of Inherited Vision loss (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2017).

Burnight, E. R. et al. CRISPR-Cas9 genome engineering: treating inherited retinal degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 65, 28–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2018.03.003 (2018).

Chen, X., Xu, N., Li, J., Zhao, M. & Huang, L. Stem cell therapy for inherited retinal diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stem Cell. Res. Ther. 14, 286. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-023-03526-x (2023).

Russell, S. R. et al. Intravitreal antisense oligonucleotide sepofarsen in Leber congenital amaurosis type 10: a phase 1b/2 trial. Nat. Med. 28, 1014–1021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01755-w (2022).

Pierce, E. A. et al. Safety and efficacy of EDIT-101 for treatment of CEP290-associated retinal degeneration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 64, 3785–3785 (2023).

Schwartz, S. D. et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium in patients with age-related macular degeneration and Stargardt’s macular dystrophy: follow-up of two open-label phase 1/2 studies. Lancet 385, 509–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61376-3 (2015).

Mahmoudi, A. et al. Predictive factors influencing the evolution of Acquired Vitelliform lesions in Intermediate Age-related Macular Degeneration eyes. Ophthalmol. Retina. 8, 367–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oret.2024.04.003 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The IT and orthoptic staff of ESA, and ophthalmologists Helen Chan, Ben Connell, Trevor Gin, Lyndell Lim, Ming-Lee Lin, Salmaan Qureshi, Richard Stawell, RC Andrew Symons and Wilson Heriot for allowing review of their patients and obtaining publication consents from their patients.

Funding

DM was awarded a Cabrini Medical Staff Scholarship for this study. Researchers were supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Fellowship (GNT#1195713: LNA), University of Melbourne Driving Research Momentum Fellowship (LNA) and a University of Melbourne Postdoctoral Fellowship (ACBJ). Centre for Eye Research Australia receives support from the Victorian Government through its Operational Infrastructure Support Program. ESA provided in-kind funding for data extraction.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.G.M., A.C.B.-J. and L.N.A . formulated the study design. H.G.M. obtained ethical permission. H.G.M. and D.M .performed data collection. Statistical calculations were performed by D.M. H.G.M. and D.M. prepared the initial manuscript, with additional drafting by A.C.B.-J. H.G.M. and D.M. prepared the Figures. L.N.A., R.H.G., T.L.E., S.S., A.J.H., W.N. and N.M.K. provided critical review. All authors have approved the submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

L.N.A. has been a consultant to Novartis and Apellis Pharmaceuticals and currently consults for Kiora Pharmaceuticals. T.L.E. has received a research grant from Novartis Pharmaceuticals. R.H.G. is a member of advisory boards of Bayer, Novartis, Apellis Pharmaceuticals, Roche-Genentech, Belite Bio, Ocular therapeutix, complement therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Character Bioscience, Janssen, AbbVie and Astellas. A.J.H. is a member of an advisory board for AbbVie, receives research support from Novotech, Genentech and Roche and is a paid lecturer for UCB. N.M.K. has received research funding and/or honoraria from Alcon, Allergan/Abbvie, Bayer, Glaukos, Johnson & Johnson Vision, NOVA Eye Medical, Santen, and VividWhite. H.G.M. has been a member of advisory boards of Novartis, Apellis Pharmaceuticals, Roche-Genentech and Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and has received travel funding from Bayer and Roche-Genentech. S.S. is the director of Eyeonic Pty Ltd which owns patent WO2021051162A1 regarding online circular contrast perimetry. The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Markakis, D., Britten-Jones, A.C., Guymer, R.H. et al. Retrospective audit reviewing accuracy of clinical diagnosis of geographic atrophy in a single centre private tertiary retinal practice in Australia. Sci Rep 15, 8528 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90516-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90516-z