Abstract

Angelica dahurica (Hoffm.) Benth. & Hook.f. ex Franch. & Sav (A. dahurica) is widely used in food, medicine and other applications due to its rich content of starch and secondary metabolites and is grown on a large scale in southwestern and northern China, where it is one of the commonly used traditional Chinese medicines(TCM). Modern studies have pointed out that the effect of soil compactness on plant root development as well as secondary metabolite synthesis is extremely significant, and auxin may play an important role in this process. However, the effect of soil compactness on coumarins synthesis in A. dahurica and the reasons for the changes in coumarins content are unknown in the current actual cultivation, which is extremely unfavorable for A. dahurica, which is dependent on the content of secondary metabolites. In this study, A. dahurica was planted in soil environments with low (5 kPa), medium (15 kPa) and high (25 kPa) soil compactness and harvested at 80, 100 and 120 d, respectively. The plant development process was quantified and the indole-3-acetic acid(IAA) content of the corresponding root tips and the total coumarins content of the primary and lateral roots were examined. We aimed to (i) clarify the effects and patterns of soil compactness on the morphology and coumarins synthesis of A. dahurica, and (ii) explore the effects of IAA on coumarins synthesis in the roots of A. dahurica in response to soil compactness stress. It was found that both too low and too high soil compactness resulted in low biomass accumulation of A. dahurica, but the latter showed a higher rate of coumarins accumulation. IAA was positively correlated (p < 0.1) with various morphological parameters and total coumarins content, suggesting that IAA may be associated with coumarins synthesis. Thereafter, we confirmed through validation experiments that IAA positively regulates coumarins synthesis in the roots of A. dahurica, and that it is intrinsic to the positive correlation between root morphology parameters and total coumarins content (p < 0.001) in A. dahurica. The results of the study showed that in response to soil compactness stress, the root system of A. dahurica regulates root morphology by secreting IAA to resist soil compactness stress, while at the same time IAA stimulates the signaling pathway for coumarins biosynthesis. This study has significant practical implications for the cultivation and quality improvement of A. dahurica.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A. dahurica is a traditional Chinese medicinal plant in the family Umbelliferae, is grown on a large scale in the northeastern and southwestern regions of China1,2. Because its roots contain rich physiological active substances, such as coumarin, volatile oil, flavonoids, alkaloids and so on,, it has been widely used in TCMs, the food industry, nutrition, and other fields, and is one of the important medicinal food plants in China3,4. The results of existing studies indicate that the root of A. dahurica has antipyretic, analgesic5, antioxidant6, anti-inflammatory7 and antitumor8 effects, while coumarins is the main material basis for the clinical efficacy of it9. Therefore, the content of coumarins is closely related to the clinical efficacy of A. dahurica.

Coumarins, the most important secondary metabolite in the roots of A. dahurica, may be biosynthesized in relation to the growth and development of itself. Soil, as one of the key environmental factors for plant growth, provides support, water and nutrients to the plant root system and also influences plant survival, distribution and function10,11,12. Soil compactness is one of the soil factors that affects almost all soil properties (soil porosity, water conductivity and nutrient effectiveness). Moderate soil compactness is beneficial for plant root development, but extreme soil compactness hinders root elongation13,14 and nutrient uptake15, leading to a severe reduction in crop yields, and is the most widespread problem faced during modern agricultural production16. In addition, soil compactness affects plant photosynthetic rate17, transpiration rate18, biomass allocation19 and secondary metabolite synthesis20. It can be seen that soil compactness plays an important role in plant growth and development and in the synthesis of secondary metabolites, and proper soil compactness is essential for the growth and quality of medicinal plants. We also found that the change of soil compactness had an effect on the root morphology and coumarins content of A. dahurica in the actual production process. however, only a few studies have shown that soil nutrients have an effect on the synthesis of coumarins in A. dahurica21, have not pointed out how the change of soil compactness affects the synthesis of coumarins. Thus, it is crucial to understand the effects and patterns of changes in soil compactness on the development of root system and coumarins accumulation of A. dahurica, and to seek out the factors affecting the biosynthesis of coumarins for the management, prediction and enhancement of A. dahurica medicinal herbs.

It is well recognized in modern findings that auxin synthesis22, signaling23 and transport24 play an instrumental role in plant root resistance to soil stress (root developmental plasticity)25,26. In addition, Goddijn O J27 et al. found that the first step of auxin synthesis may be one of the mechanisms controlling the biosynthesis of terpene indole alkaloids in periwinkle cells, and Hectors Kathleen et al.28. found that auxin regulates flavonoid concentrations during ultraviolet (UV)-B acclimation in Arabidopsis thaliana. We then hypothesized that auxin may be a key factor in assisting root remodeling and stimulating coumarins synthesis in the root system of A. dahurica in response to soil compactness stress.

In this study, we changed the soil compactness of the soil where the root system of A. dahurica was located through potting experiments, and studied the morphology of root system, the accumulation of total coumarins content, and the change rule of IAA content under different soil compactness, and explored the effect of IAA on the synthesis of coumarins in the roots of A. dahurica through validation experiments. Our aim was to solve the following two questions: (1) What are the effects and patterns of altered soil compactness on root morphology and coumarins composition of A. dahurica? (2) What is the role of IAA in the response of the root system of A. dahurica to soil compactness stress? The deeper goal of this research is to serve as a model for the cultivation and management of A. dahurica, and to lay the foundation for the study of the mechanism of quality formation in A. dahurica.

Results

Effect of soil compactness on plant biomass accumulation

It was found that the biomass accumulation of the leaves and taproot of A. dahurica varied significantly under different soil compactness treatments (Fig. 1). Overall, all three treatment groups showed an increasing and then decreasing trend, but with significant differences between treatments. Plants grown under 15 kPa soil compactness (MP) exhibited a higher rate of biomass accumulation compared to plants grown under 5 kPa (LP) and 25 kPa (HP) environments, which dominated throughout the growth phase, and which was 171.19% and 51.38% higher than LP and HP groups, respectively, at 120 d (Fig. 1A). Also, the differences between the LP and HP groups varied according to the developmental stage. At 80d and 100d, the leaf weight of LP group was 152.28% and 32.04% higher than that of HP group, but this advantage disappeared at 120d.

Similar to the leaf biomass accumulation pattern, the primary roots of the plants in the MP group exhibited a higher rate of biomass accumulation compared to the plants in the LP and HP groups and across the entire developmental stage, which increased by 183.57% and 82.69% at 100 d and 120 d, respectively. Moreover, the differences between LP and HP groups varied according to the developmental stage. At 80d and 100d, the taproot weight of LP group was 441.26% and 86.34% higher than that of HP group, but this advantage disappeared at 120d (Fig. 1B).

Leaf weight (A) and taproot weight (B) in A. dahurica grown under different soil compactness. LP (low compactness treatment group ,5 kPa), MP(moderate compactness treatment group, 15 kPa) and HP(high compactness treatment group HP, 25 kPa) represent different soil compactness treatment groups respectively. Data are the mean values (n = 9). Letters represent significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05).

Effect of soil compactness on root morphology

It was observed that the root morphology of A. dahurica varied significantly under different soil compactness treatments (Fig.S1). The response of taproot length to soil compactness varied according to developmental stage, and the taproot length of plants in the LP group was 29.11% and 140.35% higher than that of the MP and HP groups at 80 d. However, this advantage was successively eliminated by the MP and HP groups at 100 d and 120 d (Fig. 2A).This was also reflected in the taproot diameters, which were larger in the LP and MP groups than in the HP group at 80 d; at 100 d, the MP group surpassed the LP and HP groups; and at 120 d, the HP group became the largest (Fig. 2B). The growth pattern of the NLR in the different groups was different from the rest of the indicators; the NLR in the LP group remained essentially unchanged throughout the period and was maintained at about 5. The number of lateral roots in this group was dominant only at 80d. The NLR in the HP group, on the other hand, was consistently increasing, and it reached the level of the LP group at 100 d and exceeded that of the MP and HP groups at 120 d. It is interesting to note that the MP group maintained a high level of NLR at 100 d, but its NLR fell back to the initial level at 120 d (Fig. 2C).

Taproot length (A), taproot diameter (B) and NLR (C) in A. dahurica grown under different soil compactness. LP (low compactness treatment group ,5 kPa), MP(moderate compactness treatment group, 15 kPa) and HP(high compactness treatment group HP, 25 kPa) represent different soil compactness treatment groups respectively. Data are the mean values (n = 9). Letters represent significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05).

Effect of soil compactness on the accumulation of total coumarins in the root system

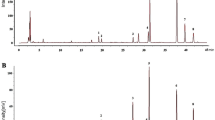

HPLC was used to determine the contents of 7-Hydroxycoumarine, byakangelicin, bergapten, oxypeucedanin, imperatorin, phellopterin and isoimperatorin of A. dahurica (Fig. 3A, B and Tab.S1). The accumulation of total coumarins content in the taproot and lateral roots of A. dahurica differed significantly under different soil compactness treatments. At 80 d the LP group was 8.38% and 47.78% higher than the MP and HP groups, but at 100 d the total coumarins content of the taproot under the LP group decreased by 12.32%, while the two higher degrees of soil campactness treatments (MP and HP groups) increased by 16.46% and 85.10%, respectively, which led to the beginning of the disadvantage of the LP. Although LP group caught up with MP group at 120 d, both were lower than HP group (Fig. 3C). Total coumarins content of lateral roots was more consistent with this performance, and it is noteworthy that total coumarins content of lateral roots was 6.22% ~ 50.06% higher than that of the corresponding primary roots under different treatments at the same time (Fig. 3D).The content data of 7 coumarins and total coumarins are shown in Tab.S2 and Tab.S3.

Total coumarins content of taproot (mg·g− 1)

Coumarins HPLC chart and content. HPLC diagram of the reference substance (A) and tissue samples of A. dahurica (B) (1.7-Hydroxycoumarine; 2.byakangelicin; 3.bergapten; 4.oxypeucedanin;5. imperatorin; 6.phellopterin; 7.isoimperatorin).Changes in total coumarins content in the taproots (C) and lateral roots (D) of A. dahurica grown under different soil compactness treatments. LP (low compactness treatment group ,5 kPa), MP (moderate compactness treatment group, 15 kPa) and HP(high compactness treatment group HP, 25 kPa) represent different soil compactness treatment groups respectively. Data are the mean values (n = 3). Letters represent significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05).

Effect of soil compactness on IAA metabolism

The trends of IAA content varied significantly under different soil compactness treatments (Fig. 4). The IAA content of LP group did not change significantly throughout the developmental period and remained at 8.5 ng/g. The IAA content of MP group decreased under 100 d and 120 d conditions, by 18.48% and 10.18%, respectively, while the IAA content of HP group increased by 30.99% and 31.22% under 100 d and 120 d conditions, respectively. MP group maintained a higher level of IAA concentration at 80 and 100 d. The IAA content of this treatment group was 70.27% and 141.90% higher than LP and HP groups at 80 d and 44.22% and 40.89% higher than LP and HP groups at 100 d, respectively. However, this advantage was surpassed by HP group at 120 d. The IAA content of HP group was 47.08% and 13.69% higher than that of LP and MP groups at 120 d, respectively.

IAA content of A. dahurica in different soil compactness treatments. LP (low compactness treatment group ,5 kPa), MP(moderate compactness treatment group, 15 kPa) and HP(high compactness treatment group HP, 25 kPa) represent different soil compactness treatment groups respectively. Data are the mean values (n = 3). Letters represent significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05).

Correlation between growth hormone, morphological indicators and total coumarins content

As expected, all indicators were positively correlated with IAA concentration (P < 0.1), except for taproot weight which was not statistically significant (Fig. 5).We also found that there were different degrees of correlations between the two morphological indicators and between morphological indicators and total coumarins content, and most of them were positive, such as leaf weight was highly significantly positively correlated with all morphological indicators except for taproot diameter (P < 0.001); the NLR was positively correlated with leaf weight and taproot length only; taproot weight, taproot diameter and taproot length were also positively correlated with the other indicators to different degrees .The total coumarins content of taproots, on the other hand, was highly significantly and positively correlated with taproot weight, taproot diameter and taproot length (P < 0.001).

Effect of IAA on root development of A. Dahurica

Effect of IAA on root morphology of A. Dahurica

The results of the study showed significant effects of IAA on root trait parameters of A. dahurica seedlings (Fig.S2). Among them, TRL, SA and NLR increased with increasing concentration of IAA treatment, while the AD was reversed (Fig. 6). Compared to the CK, TRL increased by 3.72%, 48.49%, 58.14% and 364.28% in LT, MT, HT and ST groups, respectively, although the increase in LT group was not statistically significant. SA increased by 19.58%, 29.66%, 32.10%, and 44.20%, and the number of lateral roots increased by 19.06%, 169.04%, 269.24%, and 195.23%, respectively. In addition, the differences in AD under different concentrations of IAA treatment were equally significant, with less difference between plants in LT group and CK group, but MT, HT and ST groups decreased by 20.09%, 17.70% and 22.17%, respectively.

Total root length (A), total root surface area (B), average diameter (C) and number of lateral roots (D) in A. dahurica grown under different concentrations of IAA treatment. CK(control treatment, 0 mg/L), LT(low treatment, 0.3 mg/L ),MT (medium treatment, 0.6 mg/L), HT(high treatment, 0.9 mg/L) and ST(super-high treatment, 1.2 mg/L) represent treatment groups with different concentrations of IAA, respectively. Data are the mean values (n = 15). Letters represent significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05).

Effect of IAA on coumarins accumulation

The effect of IAA on the content of coumarins in the taproots of A. dahurica seedlings is shown in Fig. 7. The results of total coumarins content measurement showed that with the increase of IAA concentration, the total coumarins content showed a trend of increasing and then decreasing (p < 0.05), and the total coumarins content of LT, MT, HT and ST groups increased by 5.69%, 16.26%, 51.74% and 27.09%, respectively, compared with the CK group. The differences of single coumarin content are shown in Tab.S4.

Changes in total coumarins content in the taproots of A. dahurica treated with different concentrations of IAA. CK(control treatment, 0 mg/L), LT(low treatment, 0.3 mg/L ),MT (medium treatment, 0.6 mg/L), HT(high treatment, 0.9 mg/L) and ST(super-high treatment, 1.2 mg/L) represent treatment groups with different concentrations of IAA, respectively. Data are the mean values (n = 3). Letters represent significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05).

Trends in relative expression of auxin response factor 2 (AdARF2).

The trend of the relative expression level of AdARF2 in the taproots was consistent with the pattern of exogenously applied IAA concentration, i.e., its expression showed a rising and then decreasing trend as the concentration of exogenously applied IAA increased (Fig. 8). the relative expression of AdARF2 in the lateral roots was lower compared with that in the taproots, indicating that the exogenously applied IAA did act in the root system of A. dahurica seedlings in this experiment, but the main site of action was in the taproots.

Relative expression of AdARF2 in the taproot and lateral roots of A. dahurica was determined by qRT-PCR under different IAA concentration treatments.CK(control treatment, 0 mg/L), LT(low treatment, 0.3 mg/L ),MT (medium treatment, 0.6 mg/L), HT(high treatment, 0.9 mg/L) and ST(super-high treatment, 1.2 mg/L) represent treatment groups with different concentrations of IAA, respectively.Data are the mean values (n = 3). Letters represent significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05).

Trends in expression of key genes for coumarins synthesis

To verify the differences in coumarins content data of plants under IAA treatment, qRT-PCR was used to detect and quantify the genes AdPAL, Ad4CL,Ad C4H, AdF6H, AdPOD, AdHCT, AdC3H, and AdCOMT in the taproots and lateral roots of A. dahurica, respectively. The positions of the six genes on the coumarins biosynthesis pathway are as follows (Fig. 9A).The results showed that the relative expression of the corresponding genes in the lateral roots were all low, and six genes in the taproots showed the same expression trend as the coumarins content (Fig. 9B and Tab.S5).Therefore, combined with the qRT-PCR results, the coumarins content data could be confirmed to be reliable.

A.Expression patterns of genes involved in coumarins biosynthesis. B.Relative expression of coumarins synthesis genes in A. dahurica taproots was determined by qRT-PCR under different concentrations of IAA treatment. CK(control treatment, 0 mg/L), LT(low treatment, 0.3 mg/L ),MT (medium treatment, 0.6 mg/L), HT(high treatment, 0.9 mg/L) and ST(super-high treatment, 1.2 mg/L) represent treatment groups with different concentrations of IAA, respectively.Data are the mean values (n = 3). Letters represent significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05).

Discussion

Effect of soil compactness on plant morphology and biomass of A. Dahurica

Plant growth and development rely to a large extent on roots, which provide almost all the nutrients and water needed for plant growth and development, so the ability of the root system to adapt to the soil environment often determines the overall development of the plant29. Our results showed that altered soil compactness significantly affected root and leaf development in A. dahurica during the early stages of plant development (80 d) (Figs. 1 and 2), which is consistent with previous findings30,31. Leaf development was delayed as soil compactness increased in the second layer of soil, which corresponds to a previous study on wheat14. In addition, similar to leaf growth, root development was similarly delayed by increased soil compactness, mainly in the form of progressively shorter taproot lengths and taproot diameters, which is consistent with the effects of soil mechanical impedance on root growth and development found by Correa José et al.32. In our results, there were almost no lateral roots in the root system of the HP group compared to the other groups in the same period, which was due to the delayed formation of lateral roots due to excessive soil compactness33. The NLR increased over time under the high compactness treatment, whereas it increased and then decreased in the low and medium compactness treatments (Fig. 2C).

The results of the correlation study showed a highly significant positive correlation (p < 0.001) between leaf weight and NLR, taproot weight, and taproot length under different soil compactness treatments, which indicates that aboveground and belowground growth are indeed linked, which is similar to the results obtained in broccoli seedlings, where the root length explains the response of leaf area to soil compactness33. With the increase of soil compactness, both leaf weight and taproot weight showed an increase and then a decrease, and both were the lowest under the 5 kPa (LP group) at 120 d. This indicated that either too high or too low soil compactness was detrimental to the biomass accumulation of A. dahurica, but too low soil compactness had a greater effect, which may be due to the drought stress induced by the too low soil compactness34,35. It can be seen that the change of soil compactness did affect the growth and development process of A. dahurica.

Effect of soil compactness stress on coumarins synthesis in the roots of A. Dahurica

Coumarins is abundantly present in the roots of A. dahurica and is one of the important components of the roots of A. dahurica for its medicinal value36. The biosynthesis of coumarins occurs through the phenylpropanoid metabolic pathway, which is a class of compounds with a phenylpropanoid α-pyranone backbone synthesized from phenylalanine catalyzed by a series of enzymes, including phenylalanine ammonia lyase (AdPAL), cinnamic acid-4-hydroxylase (AdC4H), and 4-coumaric acid-CoA ligase (Ad4CL) (Fig. 9)37,38. Many studies have shown that this class of compounds plays a key role in protecting plants from microbial infections, herbivorous predation and environmental stresses39.

In this study, we examined the total coumarins content of the taproot and lateral roots of different treatments, and the results showed that the trends of total coumarins content were similar in both sites. Total coumarins content decreased with increasing soil compactness during the pre-root development period, which may be related to the state of root development, when the root biomass was smaller and the rate of coumarins synthesis was lower in the HP group. Following this, total coumarins content increased with increasing soil compactness at 100 and 120 d, which indicates that higher soil compactness promotes the synthesis of coumarins, which is consistent with the results that coumarins are responsive to adversity as described in studies of intense light interventions and drought stress40,41. Surprisingly, the total coumarins content in lateral roots of A. dahurica was relatively higher, although it kept a more consistent trend with that of the taproots. In conclusion, the effect of changing soil compactness on coumarins in the root system of A. dahurica was extremely significant, and the rate of coumarins synthesis was related to the degree of soil compactness stress it was subjected to.

Effect of soil compactness stress on IAA concentration

The ability of the root system to adapt to the changing soil environment is called plasticity, which is mainly dependent on phytohormones42,43. IAA is one of the most important substances regulating the development of the plant root system, which assists the root system in responding to the soil environment mainly through the development of lateral roots and/or adventitious roots44,45. The pot experiment showed that changes in soil compactness had a significant effect on IAA concentration, and in conjunction with root development, it is possible that the reason for the lack of change in IAA concentration in the LP group may be that the soil compactness environment of the soil in which they were grown did not change. The IAA concentration in the MP group decreased with time, but was still higher than that in the LP group in the late stage, indicating that the MP group was subjected to higher soil compactness stress than the LP group, and that the decrease in its content in the late stage might be due to the fact that the root system had already completed its development, and that a reduction in the number of lateral roots would be beneficial to cope with drought stress in general, which is in line with the results of the related study on maize46. The IAA concentration in the HP group increased with time and exceeded that of the remaining two groups at 120 d (Fig. 4), which was attributed to the fact that root elongation was severely impeded by the high-intensity soil pressure, and it was necessary to promote the development of lateral roots through a large amount of IAA in order to counteract the high-intensity mechanical resistance and to gain access to nutrients and water.

The results of correlation analysis showed that IAA showed positive correlation with almost all morphological indicators, which is consistent with the results of a previous study47. However, this correlation was not particularly strong, which may be related to the soil environment in which the root system of plants in the LP and MP groups are located. The root elongation of A. dahurica in the LP group was not impeded and did not need to secrete too much IAA to resist soil tightness stress, but the root system of A. dahurica in this group kept elongating and accumulating biomass; The root system of A. dahurica in the MP group was faced with an increase in soil compactness when entering the second layer of soil, but not to a strong extent, and it assisted the root system to complete the normal developmental process by synthesizing large amounts of IAA in the early stage, and the demand for IAA declined in the later stage, resulting in a change in IAA concentration that appeared to be opposite to the pattern of root development. Therefore, we believe that the change of soil compactness did change the concentration of IAA in the root system of A. dahurica, and this pattern of change is the same as the results of previous studies, that is, IAA is closely related to the development of plant roots.

IAA — the key to the increase of coumarins content in the roots of A. Dahurica under soil compactness stress

Auxin is well known as a compound that affects physiological processes such as plant differentiation, development and growth. In less than ideal growing conditions, it can not only regulate plant morphology, but also affect the synthesis and accumulation of secondary metabolites in plants, including the synthesis of phenylpropane48. From the previous experiments we have realized that the change of soil compactness affected the root development and coumarins content of A. dahurica, in which IAA was inseparably linked to the root development. Meanwhile, we found a positive correlation between IAA concentration and total coumarins content, suggesting that IAA may also affect coumarins synthesis in the roots of A. dahurica, which is consistent with the results reported for ginkgo and buckwheat49,50. However, this correlation was not strong, even much less strong than that between coumarins content and root parameters, which at one time led us to believe that the increase in total coumarins content in the taproot was coming from the lateral roots, since concentration differences are a prevalent mechanism of translocation in plants. However, the changes of IAA content were correlated with the environment in which A. dahurica is found, and the biosynthesis of coumarins is a complex process, so we further carried out validation experiments to clarify whether IAA plays a role in this process.

In the validation experiment, we found that the SA, TRL, NLR(Fig. 6) and total coumarins content of the taproot (Fig. 7) of A. dahurica seedlings showed a trend of increasing first with the increase of IAA concentration, this is consistent with the findings of Chang HaPark et al. in buckwheat, that is, specific concentrations of IAA can significantly promote the accumulation of phenylpropanoid compounds49,50. Combined with the qRT-PCR results of the key genes in the coumarins biosynthesis pathway (AdPAL, AdC4H, AdC3H, Ad4CL, AdF6H, and AdCOMT) (Fig. 9), we confirmed that IAA had a promotional effect on key genes in the taproot of A. dahurica for coumarins synthesis but it had a lesser effect on the lateral roots. It can be seen that IAA stimulated the coumarins synthesis activity in the taproot while promoting the generation of more lateral roots by the roots of A. dahurica to resist soil compactness stress, which explains the strong positively correlation between the total coumarins content and the root parameters, as they are jointly regulated by IAA.

Materials and methods

Plant material and experimental design

Seeds and soil

The seeds of A. dahurica were collected from the experimental field of Sichuan Quantaitang Sichuan Angelica Industry Co, Ltd. in Suining, Sichuan Province(30°21′19.48″N, 105°27′22.90″E), the collection process was carried out with the consent of the company, and acquisition of all plant materials were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. These seeds were identified as seeds of Angelica dahurica(Fisch. ex Hoffm.)Benth.et Hook.f.var.formosana(Boiss.)Shan et Yuan by Professor Pei Jin of Chengdu University of TCM. A. dahurica (Herbarium: NAS00005410) can be identified in the Chinese Virtual Herbarium (https://www.cvh.ac.cn/index.php).The seeds are deposited in the State Bank of Chinese Drug Germplam Resources, and sown at the Wenjiang Campus of Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Chengdu, Sichuan Province(30°41′13.02″N,103°48′16.30″E).

The experimental soil was collected from the top layer of a rice paddy in Laojundu Village, Chongzhou City, Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China (collection depth < 40 cm). The soil consisted of 12% clay, 36% silt and 52% sand, and was similar in texture to that of A. dahurica’s origin, with a soil pH of 7.80 ± 0.2. The soil was air-dried and sieved through a 2 mm sieve, and mixed proportionally with several compounds and then piled up and set aside, the amount of compounds is shown in Table S6.

Experimental design

In the pot experiment, the treated soil was filled in a PVC pipe with diameter × height = 20 cm × 40 cm. The soil in the PVC pipe had two layers, the soil compactness in the first layer (10 cm) was not changed, and the second layer (30 cm) was divided into three treatments: low compactness treatment group (LP,5 kPa), moderate compactness treatment group (MP, 15 kPa), and high compactness treatment group (HP, 25 kPa), The MP group is the soil compactness condition in the actual production process.Soil compactness depends on the vertical pressure applied by the tool to change the soil compactness, which is controlled by the soil compactness tester12,51.A total of 27 pots were used for the experiment, with 9 pots per treatment group. All treatment groups are placed under uniform natural environmental conditions.Four seedlings of similar growth were subsequently transplanted into a layer of soil at 80 days after sowing, and plants were collected at 80, 100, and 120 days after transplanting; root tips were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 ℃ for subsequent determination of IAA content, and the rest of the samples were used for biomass, recording of root morphology, and determination of total coumarins content.

The seeds of A. dahurica were surface disinfected with alcohol (75%) for 30 min, rinsed five times with deionized water, and immersed in distilled water for 10 h.Seeds were germinated and grown on MS medium in a culture chamber with conditions of 25 ℃/20 ℃ (day/night), 50–70% relative humidity,100 lx light intensity and 12 h/12 h (light/dark). after 7 weeks, 30 seedlings of uniform growth were selected and transferred to MS medium containing different concentrations of IAA for further cultivation. The IAA concentrations were 0, 0.3, 0.6, 0.9 and 1.2 mg/L and were named as control treatment(CK), low treatment (LT), medium treatment (MT), high treatment (HT) and super-high treatment (ST) groups, respectively52.Roots of the plants were collected 4 days after transplantation and 15 randomly selected roots were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 ℃ for subsequent qRT-PCR experiments, while the remaining samples were used for root morphology recording and total coumarins content determination.

Experimental methods

Morphological trait analysis of root system

Morphological indicators of A. dahurica plants for pot experiments were quantified using vernier calipers and electronic scales, which included leaf weight, taproot length, taproot weight, taproot diameter, and number of lateral roots(NLR). For the validation experiments, due to the small root system of seedlings, images of the corresponding plants were collected using a scanner and analyzed using WinRhizo Pro (S) v.2004b software, and root traits measured included total root surface area (SA), total root length (TRL), Average diameter(AD), and NLR.

Quantification of total coumarins content.

Coumarins content in dried A. dahurica tissues (taproots and lateral roots) was determined using the High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)(Thermo Fisher, Ultimate 3000). Dried powder (0.5 g) from each tissue sample (taproots and lateral roots) was mixed with 25 mL of ethanol (50%) by ultrasonication (500 W, 40 HZ) for 1 h. All reference substances(7-Hydroxycoumarine, CHB201220; Byakangelicin, CHB210104; Bergapten, CHB201127; Oxypeucedanin, CHB210113; imperatorin, CHB201201; phellopterin, CHB210106; isoimperatorin, CHB210110; each 0.4 mg, HPLC ≥ 98%) were mixed thoroughly with 5 mL of ethanol (50%), aqueous solution to obtain 80 µg·mL− 1 control solution, and diluted proportionally into different concentrations of control solutions. Coumarins were detected by HPLC under these conditions: C18 chromatographic column (Agilent Eclipse Plus, 250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm); mobile phase of pure water with 0.1% formic acid (A)–Acetonitrile (B); an elution program consisting of 0–10 min, 10 %–25 % B;10–30 min, 25 %–50 % B;30–50 min, 50%–65 % B;50–55 min, 65 %–10 % 0% B; flow rate set to 1.0 mL/min; column temperature of 35℃; injection volume: 10 µL; wavelength of 280 nm53,54. All determinations were performed in triplicate for each sample.

Quantitative detection of IAA content

The IAA content of sample were analyzed using an UPLC-ESI-MS/MS system (UPLC, ExionLC™ AD; MS, Applied Biosystems 6500 Triple Quadrupole)55.

50 mg of plant sample was weighed into a 2 mL plastic microtube and frozen in liquid nitrogen, dissolved in 1 mL methanol/water/formic acid (15:4:1, V/V/V). 10 µL internal standard IAA solution (100 ng·mL− 1) was added into the extract as internal standards (IS) for the quantication. The mixture was vortexed for 10 min, then centrifugation for 5 min (12000 r/min, and 4 ℃), the supernatant was transferred to clean plastic microtubes, followed by evaporation to dryness and dissolved in 100 µL 80% methanol (V/V), and filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane filter for further LC-MS/MS analysis.The analytical conditions were as follows, LC: column, Waters ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 C18 (100 mm×2.1 mm i.d.,1.8 μm); solvent system, water with 0.04% acetic acid (A), acetonitrile with 0.04% acetic acid (B); gradient program, started at 5% B (0–1 min), increased to 95% B (1–8 min), 95% B (8–9 min), finaly ramped back to 5% B (9.1–12 min); flow rate, 0.35 mL·min-1; temperature, 40 ℃; injection volume: 2 µL.The ESI source operation parameters were as follows: ion source, ESI+/-; source temperature 550 ℃; ion spray voltage (IS) 5500 V(Positive), -4500 V (Negative); curtain gas (CUR) was set at 35 psi, respectively.IAA were analyzed using scheduled multiple reaction monitoring (MRM)56. Data acquisitions were performed using Analyst 1.6.3 software (Sciex). Each biological treatment was repeated three times.

Analysis of the quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using the TransZol Up Plus RNA Kit (Q41206TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription using the PrimeScript RT reagent Kit (ALG2107A, Takara Biomedical Technology, Beijing, China). qRT-PCR was performed using TB Green® Premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNaseH pLUS) (AM81684A Takara Biomedical Technology, Beijing, China) in a 20 µL reaction volume that contained 1 µL cDNA, 1 µL 2 µM forward primer, 1 µL 2 µM reverse primer, 10 µL 2 × SYBR Green Premix Premix pro Taq, and 7 µL RNase-free water.Th AdARF2 was selected as the basis for judging the success of exogenous application of IAA, because the expression levels of other IAA-responding genes in the root of A. dahurica were extremely low in this experiment. meanwhile, 6 genes in the coumarins biosynthetic pathway(AdPAL, AdC4H, AdC3H, Ad4CL, AdF6H, and AdCOMT) were selected for qRT-PCR validation3,40, and the actin gene was used as an internal reference control gene. The specific primers for the qRT-PCR of all genes are shown in Table S7, and the qRT-PCR amplification conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 2 min; 40 cycles at 95 °C for 5 s; and 60 °C for 30 s,95 °C for 5 s; 65 °C to 95 °C (0.5 °C/5 s). Relative expression was calculated using the 2−∆∆Ct method57, and the results were obtained for each gene using three biological replicates and three technical replicates of each sample.

Statistical analysis

Origin 2021 software was used to plot the data. SPSS 19.0 software was used for one-way ANOVA and Duncan’s method of multiple comparisons (p < 0.05). The data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Conclusions

In this study, we analyzed the process of changes in plant morphology, total coumarins accumulation, and IAA concentration of A. dahurica under low soil compactness (LP), medium soil compactness (MP), and high soil compactness (HP) treatments. Changes in plant morphological parameters showed that soil compactness had a significant effect on the growth and development of A. dahurica, and either too high or too low soil compactness was unfavorable to the accumulation of biomass in the root system of A. dahurica. At the same time, the effect of soil compactness on the coumarins in the root system of A. dahurica was extremely significant, and the rate of coumarins accumulation was related to the degree of soil compactness stress, with the HP group accumulating the largest amount of total coumarins, which was about 20% higher than that of the MP and LP groups. Therefore, moderate soil compactness is favorable for A. dahurica biomass accumulation and coumarins synthesis. In addition, the content of IAA was positively correlated with the level of soil compactness in which roots were located, and there was a positively correlation between IAA and the morphological parameters and the total amount of coumarins. Based on these results we carried out validation experiments, which showed that the degree of remodeling of the root system of A. dahurica and the synthesis of coumarins in the taproot of A. dahurica were both affected by the concentration of IAA in a concentration-dependent manner. The relative expression of key genes on the pathway of phenylpropanoid metabolism in the taproot of A. dahurica can prove this conclusion more accurately. The qRT-PCR results showed that the relative expression of genes such as AdPAL, AdC4H, AdC3H, Ad4CL, AdF6H, and AdCOMT increased with the increase of IAA concentration, whereas the expression of the corresponding genes in the lateral roots was lower, indicating that the lateral roots were not involved in the process of increasing the coumarins content of the taproot. In conclusion, we concluded from our experiments that changes in soil compactness had a significant effect on root development and coumarins synthesis in A. dahurica; in addition to promoting the development of lateral roots of A. dahurica, IAA stimulates the synthesis of coumarins in roots of A. dahurica. The results of this study can be used to improve the quality of the medicinal plant A. dahurica, and also provide a new idea to study the synthesis mechanism of secondary metabolites in A. dahurica.

Data availability

All data are included in the manuscript and supplementary information. Additional information is available upon request from the corresponding authors.

References

Kang, J. et al. Chromatographic fingerprint analysis and characterization of furocoumarins in the roots of Angelica Dahurica by HPLC/DAD/ESI-MSn technique. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 47(4–5), 778–785 (2008).

Shi, H. et al. Chemical comparison and discrimination of two plant sources of Angelicae dahuricae Radix, Angelica Dahurica and Angelica Dahurica var. Formosana, by HPLC-Q/TOF-MS and quantitative analysis of multiple components by a single marker. Phytochem Anal. 33(5), 776–791 (2022).

Zhao, L. et al. De novo transcriptome assembly of Angelica Dahurica and characterization of coumarin biosynthesis pathway genes. Gene 791, 145713 (2021).

Wu, P. et al. Analysis of the difference between early-bolting and non-bolting roots of Angelica Dahurica based on transcriptome sequencing. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 7847 (2023).

Kang, S. W. et al. Rapid identification of furanocoumarins in Angelica Dahurica using the online LC-MMR-MS and their nitric oxide inhibitory activity in RAW 264.7 cells. Phytochem Anal. 21(4), 322–327 (2010).

Yang, W. T. et al. Antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory potential of Angelica Dahurica and Rheum officinale extract accelerates wound healing in Staphylococcus aureus-infected wounds. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 5596 (2020).

Lee, H. J. et al. Angelica Dahurica ameliorates the inflammation of gingival tissue via regulation of pro-inflammatory mediators in experimental model for periodontitis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 205, 16–21 (2017).

Dong, X. D. et al. Structural characterization of a water-soluble polysaccharide from Angelica Dahurica and its antitumor activity in H22 tumor-bearing mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 193(Pt A), 219–227 (2021).

Zhao, H. et al. The Angelica Dahurica: a review of traditional uses, Phytochemistry and Pharmacology. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 896637 (2022).

Whitmore, A. P. & Whalley, W. R. Physical effects of soil drying on roots and crop growth. J. Exp. Bot. 60(10), 2845–2857 (2009).

Liu, D. et al. Effects of pH, Fe, and cd on the uptake of Fe(2+) and cd (2+) by rice. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int. 20(12), 8947–8954 (2013).

Wang, M. et al. Effects of soil compaction on plant growth, nutrient absorption, and root respiration in soybean seedlings. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int. 26(22), 22835–22845 (2019).

Bengough, A. G. et al. Root elongation, water stress, and mechanical impedance: a review of limiting stresses and beneficial root tip traits. J. Exp. Bot. 62(1), 59–68 (2011).

Colombi, T. & Walter, A. Genetic diversity under soil compaction in wheat: root number as a promising trait for early plant vigor. Front. Plant. Sci. 8, 420 (2017).

Wang, X. et al. Wheat growth responses to soil mechanical impedance are dependent on phosphorus supply. Soil. Tillage Res. 205, 104754 (2021).

Shah, A. N. et al. Soil compaction effects on soil health and cropproductivity: an overview. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int. 24(11), 10056–10067 (2017).

Zhai, Z. et al. Effects of short-term deep vertically rotary tillage on topsoil structure of lime concretion black soil and wheat growth in Huang-Huai-Hai Plain, China. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao. 28(4), 1211–1218 (2017).

Sun, Y. et al. Effects of soil compactness stress on root activity and leaf photosynthesis of cucumber. Zhi Wu Sheng Li Yu Fen Zi Sheng Wu Xue Xue Bao. 31(5), 545–550 (2005).

You, D. et al. Short-term effects of tillage and residue on spring maize yield through regulating root-shoot ratio in Northeast China. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 13314 (2017).

Hu, K. et al. Effect of different soil compaction on growth and quality of Anoectochilus Roxburghii. Fujian J. Agricultural Sci. 36(03), 271–278 (2021).

Z, J. et al. Effects of soil factors on yield and quality of Angelica Dahurica var. Formosana. Chin. Traditional Herb. Drugs. 41(06), 984–988 (2010).

Vidoz, M. L. et al. Hormonal interplay during adventitious root formation in flooded tomato plants. Plant. J. 63(4), 551–562 (2010).

Kazan, K. Auxin and the integration of environmental signals into plant root development. Ann. Bot. 112(9), 1655–1665 (2013).

Pérez-Torres, C. A. et al. Phosphate availability alters lateral root development in Arabidopsis by modulating auxin sensitivity via a mechanism involving the TIR1 auxin receptor. Plant. Cell. 20(12), 3258–3272 (2008).

Karlova, R. et al. Root plasticity under abiotic stress. Plant. Physiol. 187(3), 1057–1070 (2021).

Jansen, L. et al. Phloem-associated auxin response maxima determine radial positioning of lateral roots in maize. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 367(1595), 1525–1533 (2012).

Goddijn, O. J. et al. Auxin rapidly down-regulates transcription of the tryptophan decarboxylase gene from Catharanthus roseus. Plant. Mol. Biol. 18(6), 1113–1120 (1992).

Hectors, K. et al. The phytohormone auxin is a component of the regulatory system that controls UV-mediated accumulation of flavonoids and UV-induced morphogenesis. Physiol. Plant. 145(4), 594–603 (2012).

Cavallari, N., Artner, C. & Benkova, E. Auxin-regulated lateral Root Organogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol., 13(7). (2021).

Grzesiak, M. T. et al. Interspecific differences in root architecture among maize and triticale genotypes grown under drought, waterlogging and soil compaction. Acta Physiol. Plant., 36(12). (2014).

Nosalewicz, A. & Lipiec, J. The effect of compacted soil layers on vertical root distribution and water uptake by wheat. Plant. Soil., 375(1/2). (2014).

Correa, J. et al. Soil compaction and the architectural plasticity of root systems. J. Exp. Bot. 70(21), 6019–6034 (2019).

Colombi, T. & Walter, A. Root responses of triticale and soybean to soil compaction in the field are reproducible under controlled conditions. Funct. Plant. Biol. 43(2), 114–128 (2016).

Hura, T., Hura, K. & Ostrowska, A. Drought-stress Induced physiological and molecular changes in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(9). (2022).

Lynch, J. P. Rightsizing root phenotypes for drought resistance. J. Exp. Bot. 69(13), 3279–3292 (2018).

Hang, S. et al. Daphnetin, a coumarin in Genus Stellera Chamaejasme Linn: Chemistry, Bioactivity and therapeutic potential. Chem. Biodivers. 19(9), e202200261 (2022).

Yao, R. et al. Identification and functional characterization of a p-coumaroyl CoA 2’-hydroxylase involved in the biosynthesis of coumarin skeleton from Peucedanum Praeruptorum Dunn. Plant. Mol. Biol. 95(1–2), 199–213 (2017).

Rodrigues, J. L. & Rodrigues, L. R. Biosynthesis and heterologous production of furanocoumarins: perspectives and current challenges. Nat. Prod. Rep. 38(5), 869–879 (2021).

Naoumkina, M. A. et al. Genome-wide analysis of phenylpropanoid defence pathways. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 11(6), 829–846 (2010).

Huang, Y. et al. Effects of light intensity on physiological characteristics and expression of genes in Coumarin Biosynthetic pathway of Angelica Dahurica. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 23(24). (2022).

Walker, D. J. et al. Accumulation of furanocoumarins by Bituminaria bituminosa in relation to plant development and environmental stress. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 54, 133–139 (2012).

Motte, H. & Beeckman, T. The evolution of root branching: increasing the level of plasticity. J. Exp. Bot. 70(3), 785–793 (2019).

Jia, Z., Giehl, R. F. H. & von Wirén, N. Nutrient-hormone relations: driving root plasticity in plants. Mol. Plant. 15(1), 86–103 (2022).

Shekhar, V. et al. The role of plant root systems in evolutionary adaptation. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 131, 55–80 (2019).

Ristova, D. & Busch, W. Natural variation of root traits: from development to nutrient uptake. Plant. Physiol. 166(2), 518–527 (2014).

Zhan, A., Schneider, H. & Lynch, J. P. Reduced lateral Root branching density improves Drought Tolerance in Maize. Plant. Physiol. 168(4), 1603–1615 (2015).

Zhao, Y. Auxin biosynthesis and its role in plant development. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 61, 49–64 (2010).

Çakmakçı, R., Mosber, G., Milton, A. H., Alatürk, F. & Ali, B. The effect of auxin and auxin-producing bacteria on the growth, essential oil yield, and composition in medicinal and aromatic plants. Curr. Microbiol. 77(4), 564–577. (2020).

Guo, J. et al. Regulation of flavonoid metabolism in ginkgo leaves in response to different day-night temperature combinations. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 147, 133–140 (2020).

Park, C. H. et al. Influence of indole-3-acetic acid and gibberellic acid on phenylpropanoid accumulation in common buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) sprouts. Molecules, 22(3). (2017).

Montagu, K. D., Conroy, J. P. & Atwell, B. J. The position of localized soil compaction determines root and subsequent shoot growth responses. J. Exp. Bot. 52(364), 2127–2133 (2001).

Liu, C. et al. Effects of exogenous auxin on mesocotyl elongation of sorghum. Plants (Basel). 12(4). (2023).

Ieri, F., Pinelli, P. & Romani, A. Simultaneous determination of anthocyanins, coumarins and phenolic acids in fruits, kernels and liqueur of Prunus mahaleb L. Food Chem. 135(4), 2157–2162 (2012).

Wang, M. et al. Determination of coumarins content in Radix Angelicae dahuricae by HPLC and UV. Zhong Yao Cai. 27(11), 826–828 (2004).

Yong, H. Y. et al. Early detection of metabolic changes in drug-induced steatosis using metabolomics approaches. RSC Adv. 10(67), 41047–41057 (2020).

Kim, R. et al. Quantitative analysis of auxin metabolites in lychee flowers. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 85(3), 467–475 (2021).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25(4), 402–408 (2001).

Funding

The work was supported by National Interdisciplinary Innovation Team of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. ZYYCXTD-D-202209) and Key R&D Projects of Sichuan Science and Technology Plan (No. 2023YFS0338, 2022YFS0582 and 2020YFN0152).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, T.Z.,X.Z. and J.P.; methodology, T.Z. and X.Z.; validation, X.Z, X.C. and C.H.; investigation, X.Z. and Q.W.; formal analysis, X.Z.; writing—original draft, X.Z.; supervision, Y.Z.,Q.W.and J.P.; writing—review and editing, X.Z., T.Z. and Q.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, X., Chen, X., Huang, C. et al. Effect of IAA on coumarins synthesis in Angelica dahurica under soil compactness stress. Sci Rep 15, 6148 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90647-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90647-3