Abstract

This research shows the utilization of various tree-based machine learning algorithms with a specific focus on predicting Salicylic acid solubility values in 13 solvents. We employed four distinct models: cubist regression, gradient boosting (GB), extreme gradient boosting (XGB), and extra trees (ET) for correlation of drug solubility to pressure, temperature, and solvent composition. The dataset was preprocessed using the Standard Scaler to standardize it, ensuring each feature has a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, followed by outlier detection with Cook’s distance. Hyperparameter optimization made using the Differential Evolution (DE) method improved the performance of models. Monte Carlo Cross-Valuation was used in evaluation of the models. Measures including the R2 score, Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) helped to measure their performance. With an R2 value of 0.996, the Extra Trees model displayed remarkable accuracy and consistency, so showing better performance than other models. This study emphasizes the resilience of ensemble methods in capturing intricate data patterns and their effectiveness in regression tasks for application of pharmaceutical manufacturing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Knowing the solubility of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) is valuable for pharmaceutical manufacturing as the solubility is used in some processes such as crystallization of APIs1,2. Crystallization process is driven by reducing API solubility in the solvent which can be done via different means such as cooling crystallization, antisolvent addition, etc.3,4,5,6. If the process cannot operate efficiently for crystallization, sometimes the solvent is swapped to enhance the efficiency of crystallization which needs selection of proper solvent7. So, the solubility of API in various solvents should be precisely determined for successful operation of API crystallization in pharmaceutical manufacturing of solid-dosage formulations. Experimental methods such as gravimetric technique can be used for measuring solubility at various solvents and temperatures. However, this method is tedious when it comes to a large number of solvents. So, other methods should be developed for estimation of solubility of APIs. From the practical point of view, solubility prediction and screening solvent is of great importance to save time and cost for improving crystallization process in pharmaceutical manufacture.

Methods of computation can be employed for evaluation and estimation of APIs solubility in a wide range of solvents. In these methods, a number of experimental solubility data are collected and used for fitting empirical models. Thermodynamic models are primarily utilized in correlation of solubility dataset as a function of temperature8,9. Some optimization techniques are needed for fitting thermodynamic models to experimental solubility data. However, thermodynamic models are not facile to apply for wide range of drugs and conditions due to their complexity implementation. Also, methods based on quantum chemical calculations and molecular modeling can be utilized to determine the drug solubility. Bjelobrk et al.10 developed a methodology based on molecular dynamics (MD) simulation to calculate the solubility of organic crystals in different solvents. The equilibrium free energy was calculated to predict the solubility values. Despite the fully predictive nature of MD calculations, the method is computationally challenging and needs huge amounts of time and resources for a large dataset of medicines.

So, data-driven models such as Machine Learning (ML) models have been recently developed in estimation of APIs solubility in different solvents utilizing various algorithms for learning the pattern of dataset11,12,13,14. ML models are able to make correlation of solubility to pressure, temperature, and any other inputs. Greater accuracy has been attained by using ML models compared to the thermodynamic methods for solubility data. ML uses statistical methods to independently learn patterns from data, without relying on predefined models, making it effective for capturing complex behaviors that traditional models might miss15. In artificial intelligence (AI), ML is a growing discipline focused on developing algorithms and statistical models enabling computers to carry out modeling and prediction tasks without explicit programming directions16,17. ML techniques have shown greater performance compared to thermodynamic models in fitting large dataset. These highly useful algorithms in many fields, including engineering, healthcare, and finance gather knowledge from data, recognize patterns, and make decisions with least human involvement18.

Liu et al.19 developed ML models for correlation of drug solubility in solvent based on inputs including pressure and temperature. Adaboost algorithm was utilized to enhance the accuracy of models in predicting the drug solubility in supercritical solvent. Capecitabine drug was considered for the analysis, and the boosted MLP model indicated the best accuracy with RMSE value of 1.71. The combined method of ML and thermodynamic COSMO-RS was used for estimating drug solubility for co-crystallization which indicated great accuracy for a wide range of coformers considering the Hansen solubility parameters, while the inputs are molecular descriptors of coformers20. For a given and wide range of parameters, ML models have shown great accuracy in estimation of drug solubility. For crystallization of APIs, it is of great importance to evaluate the drug solubility in mixed range of solvents so that the best solvent can be selected to enhance the yield of crystallization.

Because of their adaptability, interpretability, and strong predictive powers, tree-based models in ML have become rather popular and are therefore essential tools for handling complex regression problems21. Key methods include Cubist regression, Gradient Boosting (GB), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB), and Extra Trees (ET), each offering unique advantages. Cubist regression combines rule-based modeling with linear regression, effectively capturing both linear and non-linear patterns22. Gradient-based methods such as GB and XGB improve model accuracy by iteratively rectifying errors from preceding models, thus augmenting robustness. The Extra Trees model enhances prediction by incorporating randomness in feature selection and threshold splitting, thereby increasing model diversity and mitigating overfitting23.

These models’ demonstrated ability to capture complex data patterns and preserve high accuracy and consistency justifies their use in this work, which attempts to solve problems with solubility value estimation. We efficiently link solubility with many parameters, including temperature and solvent composition, by using tree-based models. Particularly, our analysis reveals that the ET model, with a R2 score of 0.996, stands out for its generalizing and accuracy powers. This work highlights their possible use in pharmaceutical manufacturing and offers understanding of the application of advanced ML approaches for solubility prediction.

The main contributions of this paper include the application and comparison of these advanced tree-based models, the implementation of hyperparameter optimization using Differential Evolution (DE), and a thorough evaluation using Monte Carlo Cross-Validation (MCCV) to ensure robust and reliable results. The models are used to correlate the solubility of Salicylic acid to pressure, temperature, and solvents composition. The ML models integrated optimizer (DE) have been developed for the first time to correlate the drug solubility (salicylic acid) in mixed solvents. This study highlights the resilience and efficacy of ensemble methods in complex regression tasks, providing a comprehensive analysis that can serve as a valuable reference for future research in this area.

Dataset of drug solubility

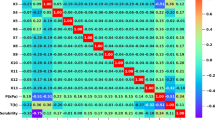

The dataset analyzed in this study are for the solubility of drug which have been taken from24, consists of 217 data points and 15 input features (see Table 1). The Salicylic acid solubility is the sole target output of this study. Data have been collected for drug solubility in 13 different solvents with various compositions. All solvents used in the models along with their notation are listed in Table 1. X refers to the composition of each solvent in mole fraction. Also, statistics of the dataset is shown in Table 2.

Figure 1 illustrates the distributions of solubility, temperature, and pressure. The solubility distribution is skewed, with most samples having low values and fewer instances of high solubility, potentially affecting regression models due to outliers. Temperature and pressure are more uniformly distributed, with temperature showing slight skewness. These distributions guide preprocessing, particularly standardization and outlier management.

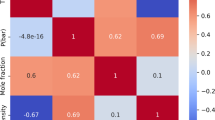

Figure 2 illustrates the Pearson correlation heatmap for all variables, displaying both the magnitude and direction of linear relationships among features. The Pearson correlation coefficient \({r}_{xy}\) quantifies the strength of the linear relationship between two parameters, x and y, and is calculated as25:

where \({x}_{i}\) and \({y}_{i}\) are individual sample points, and \(\overline{x }\) and \(\overline{y }\) are the mean values of x and y, respectively. High positive or negative correlations between certain features imply redundancy, meaning these features convey similar information, which can lead to model overfitting if not addressed. In contrast, weak correlations with the target variable (e.g., solubility) suggest the need for ensemble modeling techniques to effectively capture non-linear or complex relationships that single models might overlook. This heatmap thus aids feature selection and model interpretation, allowing for a more focused understanding of feature importance and interactions within the dataset.

Methodology

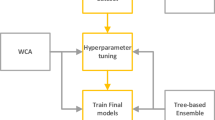

This investigation assesses the efficacy of various tree-based ML models in predicting solubility values. Research methodology involves data preprocessing, model assortment, hyperparameter tuning, and model assessment. The dataset was first preprocessed using normalization techniques to ensure that the data scale was consistent. This was followed by outlier detection using Cook’s distance. The study employed four distinct regression models: Cubist Regression, Gradient Boosting (GB), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB), and Extra Trees (ET).

We performed hyperparameter optimization using the Differential Evolution (DE) method, which is well-known for its resilience in searching high-dimensional spaces, to raise the performance of the model. The models were evaluated using Monte Carlo Cross-Validation (MCCV) to ensure the reliability and stability of the results. The performance metrics used are the R2 score, Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE). These metrics provide a comprehensive assessment of each model’s accuracy and predictability. This methodology ensures a systematic and structured approach to the development and evaluation of models, with a focus on the benefits of using ensemble methods for regression tasks. The following sections offer an elaborate explanation of the essential elements of the methodology.

This study, conducted using a Python 3.10 project, employs `sklearn`, `matplotlib`, `numpy`, and `bejoor` to implement a Differential Evolution (DE) optimizer. The `sklearn` library is crucial for model development. We preprocess data using `StandardScaler` for uniform feature scaling and employ DE (from `bejoor`) for hyperparameter optimization, enhancing R2 and MAE scores via cross-validation. Model performance and data distribution visualizations are produced with `matplotlib`, whereas `numpy` enables efficient data manipulation across matrices. This method seeks to improve predictive precision and clarity in IoT attack detection.

Data preparation

During the Data Preparation phase, we initially used the Standard Scaler for standardization, ensuring that all features have a consistent mean and standard deviation, which is essential for the effectiveness of numerous ML algorithms. This technique standardizes the data, transforming it to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. This improves the effectiveness of the model in managing the characteristics.

Additionally, we employed Cook’s distance as a method for outlier detection. Cook’s distance is a statistical method for outlier detection, primarily used in regression analysis. The technique quantifies the change in the regression coefficients when that particular point is omitted, so assessing the effect of individual data points on the fit of the regression model. Points with a high Cook’s distance value are regarded as influential outliers because their removal has a substantial impact on the model parameters26,27.

This approach offers a robust and reliable technique for identifying influential data points that have the capacity to greatly affect the outcomes of a regression analysis. However, its effectiveness is limited when working with datasets that have a large number of dimensions and in situations that involve large-scale data. This is primarily attributed to its significant dependence on regression diagnostics, which can be computationally demanding. Nevertheless, Cook’s distance remains a valuable tool for pinpointing outliers in compact, well-defined regression situations, furnishing essential insights into the stability and reliability of the regression model.

To analyze the models accurately, we divided the dataset into training/validation and test sets. We used 90% of the data for training and validation, which allows the model to learn and optimize its parameters, while the remaining 10% was set aside as a test set. This split was done randomly to ensure that both subsets are representative of the entire dataset, providing an unbiased measure of how well the model performs on new, unseen data.

Differential evolution (DE) optimization algorithm

Differential Evolution (DE) is a robust stochastic optimization algorithm renowned for its effectiveness in navigating high-dimensional search spaces to locate the global optimum of a given function. As a prominent member of the Evolutionary Algorithms (EA) family, DE is distinguished by its simplicity and efficacy28,29.

The core of DE lies in iteratively refining a population of potential solutions, represented as vectors in the search space. The algorithm starts by randomly or systematically initializing the population. In each iteration, DE generates a new candidate solution by combining three randomly chosen individuals: the base, target, and donor vectors. A donor vector is formed by adding the scaled difference between the base and target vectors to a third individual, creating a mutation vector.

The scaling factor, which determines the extent of the difference vector, is typically set through experimentation. The donor vector is then compared to the target vector, and the better-performing solution is carried forward to the next generation.

DE algorithm continues this procedure until a predefined stopping condition is satisfied. Differential Evolution has demonstrated its efficacy as a potent optimization technique in various domains, encompassing function optimization, parameter adjustment, feature selection, and ML30,31.

The choice of Differential Evolution (DE) over more conventional techniques such as random search and grid search was motivated by DE’s superior efficiency in exploring high-dimensional and continuous search spaces. Unlike grid search, which exhaustively evaluates a fixed set of hyperparameter combinations, or random search, which selects configurations randomly, DE iteratively refines a population of candidate solutions by applying evolutionary strategies. This enables DE to more effectively converge toward optimal solutions with fewer evaluations, particularly beneficial when optimizing complex models.

Also, DE was preferred over Bayesian optimization (BO) due to DE’s ability to efficiently explore high-dimensional, noisy, and complex search spaces without assumptions about smoothness. While BO excels in smooth, low-dimensional spaces, DE’s population-based approach provides more robust global exploration and scalability, making it more effective for challenging optimization tasks.

In this study, we used a fitness function designed to maximize model performance by simultaneously optimizing the mean R2 score and minimizing the Maximum Error across Monte Carlo Cross-Validation (MCCV) iterations. Our fitness function, F, is given by:

where \(\text{MCCV mean }{\text{R}}^{2}\) is the average R2 score across MCCV runs, \(\text{Max Error}\) is the maximum error, and \(\epsilon\) is a small constant (0.000001 here) added to prevent division by zero. This formulation guarantees that the algorithm emphasizes both superior predictive accuracy and error reduction. The principal DE parameters employed in this optimization are the population size (120), crossover probability (0.8), and scaling factor (0.5), all chosen to improve convergence.

Cubist regression model

Cubist regression is a method that combines rule-based modeling with linear regression to extend the capabilities of regression trees. The procedure includes developing a model through establishing a set of rules and subsequently utilizing a regression model on the data that meets each rule. The structure of the model allows for capturing both non-linear connections using the tree structure and linear patterns through the application of linear regression models22,32. The key steps in Cubist regression include33:

-

Building Regression Trees: Initially, the model generates a regression tree by iteratively dividing the data according to feature values. Each terminal node within the tree encapsulates a rule (or condition) that delineates a subset of the data.

-

Fitting Linear Models: For each rule (or leaf node), the model fits a linear regression model using the data that meets the conditions of that rule.

The prediction for a new instance x is given by the following equation:

where R stands for the total number of rules, \({w}_{i}\) denotes the weight associated with the i-th rule, and \(\widehat{{y}_{i}}\left(x\right)\) is the prediction from the linear regression model associated with the i-th rule.

The weights \({w}_{i}\) are typically determined based on the rule’s accuracy and the instance’s distance from the rule’s decision boundary.

Extra tree regression (ET)

The Extra Trees (ET) algorithm utilizes a set of decision tree models to make predictions about the target variable34. Decision trees are built by employing a randomized split-point selection mechanism. This approach increases the diversity and decreases the correlation between decision trees in comparison to the decision trees used in Random Forest23,35.

Let’s begin by establishing the notation employed in ET. Suppose we have a set of \(\left(X,y\right)\) for training, while \(X=\{{x}_{1},{x}_{2},\dots ,{x}_{n}\}\) denotes the input features, and \(y=\{{y}_{1},{y}_{2},\dots ,{y}_{n}\}\) represents the associated target values. The objective of ET is to derive a mapping function \(f: X \to y\) that is able to accurately forecast the output \({y}_{i}\) for the input \({x}_{i}\) 36.

The fundamental component of ET model is the Extra Tree (referred to as tree for brevity), which shares similarities with a Decision Tree but also possesses notable distinctions. Extra Trees, like Decision Trees, divide the feature space recursively into binary segments before making predictions. Nevertheless, there are two significant differences37,38:

-

Random Feature Selection: Extra Trees split a random subset of features at each node instead of all features like Decision Trees. Randomness increases tree diversity and decreases correlation.

-

Random Thresholds: Extra Trees employ a strategy of using random thresholds within the range of each feature during the split process, rather than determining the optimal threshold. This enhances the variety and robustness.

ET Regression generates multiple trees with various random subsets of features and thresholds, resulting in a diverse ensemble of models.

The outputs of every single tree are combined to generate predictions employing the ensemble of trees. The average of the predictions from every tree determines the last prediction \({y}_{\text{pred}}\) for regression uses:

Here, N signifies the count of trees in ET, and \({f}_{i}\left(X\right)\) denotes the prediction generated by the i-th tree. The architecture of this model is depicted in Fig. 3.

Gradient boosting and extreme gradient boosting

Gradient Boosting is a robust ML approach which can be adopted for either regression or classification. The fundamental concept underlying gradient boosting is to amalgamate the advantages of multiple feeble models, usually decision trees, in order to generate a robust predictive model39,40.

In gradient boosting, the model is built stage by stage, and new models are added to improve the performance of the model. Specifically, at each stage, the model attempts to minimize a loss function by adding a new model that predicts the residual errors of the previous models. This is accomplished by fitting the new model to the gradient of the loss function in relation to the predictions of the ensemble of models at that point. Every new model is essentially trained to fix errors made by the combined influence of past models.

The process starts with a model initialized to a constant prediction. Subsequent models are trained to predict the negative gradient of the loss function, indicating the steepest descent direction. These models are combined iteratively, updating predictions to minimize overall error. This results in a composite model capable of capturing complicated data patterns effectively.

Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB), or XGBoost, is a robust ML that builds a predictive model by combining multiple weaker models, usually decision trees. It is widely favored for its high performance and efficiency in processing large datasets41. It builds an ensemble of decision trees in an additive manner to minimize a specified objective function. The objective function (\(\mathcal{L}\left(\upphi \right)\)) consists of a convex loss function \(\text{l}\) (such as MSE) and a regularization term (\(\Omega \left(f\right)\)), defined as42:

where \(\Omega \left(f\right)=\upgamma T+\frac{1}{2}\uplambda |w{|}^{2}\), with T being the quantity of leaves, \(w\) the leaf weights, and \(\upgamma\) and \(\uplambda\) the regularization parameters.

A new tree \({f}_{t}\) is included to the model at every iteration t to update the prediction \(\widehat{{y}_{i}}\):

To optimize the objective, XGBoost uses second-order Taylor expansion, calculating gradients \({g}_{i}\) and Hessians \({h}_{i}\) 43:

The optimization of the tree structure involves selecting split points that maximize the gain:

where \({G}_{L}\) and \({H}_{L}\) are the sums of gradients and Hessians for the left child, and \({G}_{R}\) and \({H}_{R}\) for the right child. This results in a finely tuned, accurate model capable of handling various regression tasks effectively.

Evaluation method

The evaluation of the models was conducted through a systematic approach to ensure the robustness and reliability of the results. The following steps outline the evaluation methodology:

-

1.

Cross-Validation: To assess the models’ efficacy, we employed Monte Carlo Cross-Validation (MCCV) with 20 iterations. This method utilizes a stochastic process to partition the dataset into multiple training and testing sets (specifically, a 4:1 ratio from 90% of the total training data, with 10% allocated for final model testing), facilitating the evaluation of model stability and performance across diverse data segments. The R2 score and standard deviation were calculated to evaluate the models’ reliability and predictive performance.

-

2.

Model Comparison: Several regression models, including ET, GB, XGB, and Cubist regression, were trained and tested.

-

3.

Error Analysis: The final models’ error rates were examined to determine why the predicted and actual values differed. RMSE gives more weight to larger errors and MAE averages absolute errors, so they were chosen to measure prediction accuracy directly. Results section test data error rates (10% of dataset).

This comprehensive evaluation approach ensured that the selected models were rigorously tested and compared, leading to a reliable selection of the best-performing model for the given regression task.

Results and discussion

The metrics that are evaluated include the mean R2 score, the standard deviation from Monte Carlo Cross-Validation (MCCV), the RMSE, and the MAE. Tables 3 and 4 present a thorough summary of the results, demonstrating the predictive precision and reliability of each model in a straightforward and concise manner.

The optimized hyperparameters derived from Differential Evolution (DE) for the models are as follows. The hyperparameters chosen for Gradient Boosting are: `Number of estimators = 230`, `learning rate = 0.9734`, `criterion = ‘squared error’`, and `tol = 0.1503`. Extreme Gradient Boosting is configured with a maximum depth of 19, a learning rate of 0.0406, 89 estimators, an objective of ‘squared error’, and a booster type of ‘dart’. The Extra Trees model employs `Number of estimators = 10`, `criterion = ‘absolute error’`, `max depth = 10`, and `max features = 15`. The Cubist model is ultimately configured with `committees = 18` and `neighbors = 4`. The ‘Squared Error’ loss function used for all tree-based methods in this study.

The analysis of Tables 3 and 4, along with Fig. 4, provides clear evidence that the Extra Trees (ET) model is the best-fit model for this study. Table 3 reveals that the ET model achieves a mean R2 score of 0.996781, which is markedly above the scores of other models such as Gradient Boosting, Extreme Gradient Boosting, and Cubist Regression. The low standard deviation of 0.060889 for the ET model further emphasizes its consistency and reliability across multiple cross-validation iterations, indicating that it consistently captures the variance in the data. The total error (difference between experimental and predicted values) calculated for the best model (Extra Trees) is lower compared to the previous work24 due to the use of advanced algorithm for optimization in this study which reduced the total error.

Table 4 supports these findings by showing that the ET model has the lowest RMSE of 0.013539 and MAE of 0.00800445. These measures show that, among other models such as Gradient Boosting, which has higher error rates, the ET model generates the most exact predictions with the lowest amount of error. Confirming their robustness and accuracy, the lower error rates show the great generalizing capacity of the ET model to new data.

Finally, Fig. 4 visually demonstrates the performance of the models by comparing actual versus predicted solubility values. In this Figure, the final models were evaluated using hyperparameters optimized by DE for best performance. The ET model is expected to exhibit predicted values that closely correspond to the actual values, indicating a high level of model accuracy. Points for the ET model would be clustered near the line of equality, where predicted values equal actual values, further supporting its efficacy. Overall, the combination of high predictive accuracy, low error rates, and visual validation confirms that the ET model is the most suitable choice for predicting solubility in this study.

The underperformance of Gradient Boosting (GB) and Cubist Regression compared to the Extra Trees (ET) model may be attributed to several factors. First, GB may have been affected by its sensitivity to hyperparameter settings; while efforts were made to optimize these, the model could not capture complex patterns as effectively as ET. Additionally, GB’s reliance on sequential learning may have limited its robustness to noise and outliers in the dataset. Similarly, Cubist Regression, which combines rule-based and linear modeling, may struggle with high-dimensional and non-linear interactions among features, which the ET model handles more adeptly through its randomized split and feature selection process. These findings highlight the importance of model architecture in capturing complex solubility patterns in diverse solvents.

Figure 5 displays the feature importance rankings as determined by the Extra Trees (ET) model. The analysis identifies the input features that had the highest impact on the model’s predictions, offering valuable insights into the factors that exert the most influential effect on solubility. It is observed that X2 which is water content (mole fraction) is the most significant factor affecting the solubility. Afterward, temperature is the most important factor which is already known to alter the solubility of drugs in solvents. As seen, pressure does not have significant effect on the API solubility variations which is attributed to the incompressibility of solvents whose properties do not change with pressure.

Figure 6 illustrates the partial dependence of solubility on the two most important features while keeping other input features constant at their median values. It visualizes how changes in these key features influence the predicted solubility, helping to understand their relationship with the target variable. According to Fig. 6, as the water content (X2) is increased in the solvent, the solubility of Salicylic acid is reduced which is due to the poor water solubility of this API in aqueous solutions. Basically, most APIs are of poor solubility in aqueous media. On the other hand, solubility is enhanced with increasing temperature, and it is correctly predicted by the ML models.

Figure 7 presents a contour plot that illustrates the relationship between solubility and the two most important features identified by the Extra Trees model. The plot shows how solubility varies as these two features change, while keeping the other features constant at their median values. This visualization helps in understanding the interaction between these key features and their combined effect on solubility. The highest API solubility has been obtained at the highest temperature and the lowest X2 value. Figure 8 is the same for pressure and temperature as inputs which confirms sharp variations of solubility with temperature compared to the pressure.

Finally, Fig. 9 illustrates SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values, which clarify feature contributions to individual predictions by showing the impact and direction of each feature’s effect on the model’s response. Features are ranked by importance, with the most influential at the top. Each point indicates a SHAP value for a feature and instance, with positive values pushing predictions higher and negative values lowering them. The color gradient (blue to red) indicates feature values, revealing whether high or low values amplify the feature’s influence. This visualization offers a comprehensive view of how key features interact to shape model predictions, enhancing the interpretability of the Extra Trees model.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study highlights the superior performance of the Extra Trees (ET) model in predicting solubility values of Salicylic acid in various solvents, achieving an impressive R2 value of 0.996, which significantly surpasses the performance of other models like Gradient Boosting, Extreme Gradient Boosting, and Cubist regression. The efficacy of the Differential Evolution (DE) method for hyperparameter optimization is highlighted by its successful application, which leads to improved model performance. Monte Carlo Cross-Validation (MCCV) is employed to enhance the dependability and resilience of the outcomes. The results highlight the effectiveness of ensemble methods, specifically Extra Trees, in managing intricate regression tasks and accurately capturing complex data patterns with high precision and reliability.

This study establishes a solid foundation for further research in ML applications for regression tasks, particularly in predicting chemical properties such as solubility. The results provide valuable insights that can support the design and optimization of crystallization processes in pharmaceutical manufacturing of small-molecule APIs.

Future research should investigate the robustness and generalizability of these models using datasets with broader feature ranges to evaluate their performance with data outside the training range. Testing on such expanded datasets would reveal the models’ ability to handle unseen scenarios, ensuring reliability and adaptability across diverse conditions. Additionally, validating the models with experimental solubility data could assess their real-world applicability, while incorporating transfer learning techniques might enhance their adaptability to datasets with different characteristics or limited availability, enabling broader applications in pharmaceutical research.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Barhate, Y. et al. Population balance model enabled digital design and uncertainty analysis framework for continuous crystallization of pharmaceuticals using an automated platform with full recycle and minimal material use. Chem. Eng. Sci. 287, 119688 (2024).

Pu, S. & Hadinoto, K. Habit modification in pharmaceutical crystallization: A review. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 201, 45–66 (2024).

Fang, L. et al. Controlled crystallization of metastable polymorphic pharmaceutical: Comparative study of batchwise and continuous tubular crystallizers. Chem. Eng. Sci. 266, 118277 (2023).

Lahiq, A. A. & Alshahrani, S. M. State-of-the-art review on various mathematical approaches towards solving population balanced equations in pharmaceutical crystallization process. Arab. J. Chem. 16(8), 104929 (2023).

Reddy, P. S. et al. Studies on crystallization process for pharmaceutical compounds using ANN modeling and model based control. Digit. Chem. Eng. 8, 100114 (2023).

Crafts, P., Chapter 2—The Role of Solubility Modeling and Crystallization in the Design of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients, in Computer Aided Chemical Engineering, K.M. Ng, R. Gani, and K. Dam-Johansen, Editors. 2007, Elsevier. p. 23–85.

Papadakis, E., Tula, A. K. & Gani, R. Solvent selection methodology for pharmaceutical processes: Solvent swap. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 115, 443–461 (2016).

Ramalingam, V. & Garlapati, C. UNIFAC and Wilson models to correlate solubility of pharmaceutical compounds in supercritical carbon dioxide. Fluid Phase Equilib. 586, 114191 (2024).

Wünsche, S. et al. Experimental and model-based approach to evaluate solvent effects on the solubility of the pharmaceutical artemisinin. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 200, 106826 (2024).

Bjelobrk, Z. et al. Solubility prediction of organic molecules with molecular dynamics simulations. Cryst. Growth Des. 21(9), 5198–5205 (2021).

Abouzied, A. S. et al. Advanced modeling and intelligence-based evaluation of pharmaceutical nanoparticle preparation using green supercritical processing: Theoretical assessment of solubility. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 48, 103150 (2023).

Chen, C. Artificial Intelligence aided pharmaceutical engineering: Development of hybrid machine learning models for prediction of nanomedicine solubility in supercritical solvent. J. Mol. Liq. 397, 124127 (2024).

Meng, D. & Liu, Z. Machine learning aided pharmaceutical engineering: Model development and validation for estimation of drug solubility in green solvent. J. Mol. Liq. 392, 123286 (2023).

Aldawsari, M. F., Mahdi, W. A. & Alamoudi, J. A. Data-driven models and comparison for correlation of pharmaceutical solubility in supercritical solvent based on pressure and temperature as inputs. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 49, 103236 (2023).

Sivakumar, N., Mura, C. & Peirce, S. M. Innovations in integrating machine learning and agent-based modeling of biomedical systems. Front. Syst. Biol. 2, 959665 (2022).

Vo Thanh, H. et al. Data-driven machine learning models for the prediction of hydrogen solubility in aqueous systems of varying salinity: Implications for underground hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 55, 1422–1433 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Catalyzing net-zero carbon strategies: Enhancing CO2 flux Prediction from underground coal fires using optimized machine learning models. J. Clean. Prod. 441, 141043 (2024).

Ramentol, E., Olsson, T. & Barua, S. Machine learning models for industrial applications, in AI and Learning Systems-Industrial Applications and Future Directions. IntechOpen (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Machine learning based modeling for estimation of drug solubility in supercritical fluid by adjusting important parameters. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 254, 105241 (2024).

Mahdi, W. A. & Obaidullah, A. J. Combination of machine learning and COSMO-RS thermodynamic model in predicting solubility parameters of coformers in production of cocrystals for enhanced drug solubility. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 253, 105219 (2024).

Gottard, A., Vannucci, G. & Marchetti, G. M. A note on the interpretation of tree-based regression models. Biom. J. 62(6), 1564–1573 (2020).

Fernández-Delgado, M. et al. An extensive experimental survey of regression methods. Neural Netw. 111, 11–34 (2019).

Cutler, A., Cutler, D. R. & Stevens, J. R. Tree-based methods. In High-Dimensional Data Analysis in Cancer Research 1–19 (Springer, 2008).

Hashemi, S. H., Besharati, Z., & Hashemi, S. A. Salicylic acid solubility prediction in different solvents based on machine learning algorithms. Digit. Chem. Eng., 100157 (2024).

Lee Rodgers, J. & Nicewander, W. A. Thirteen ways to look at the correlation coefficient. Am. Stat. 42(1), 59–66 (1988).

Dı́az-Garcı́a, J. A. & González-Farı́as, G. A note on the Cook’s distance. J. Stat. Plan. Infer. 120(1–2), 119–136 (2004).

Cook, R. D. Detection of influential observation in linear regression. Technometrics 19(1), 15–18 (1977).

Kumar, B. V., Oliva, D. & Suganthan, P. N. Differential Evolution: from Theory to Practice. Vol. 1009. Springer (2022).

Storn, R. & Price, K. Differential evolution—A simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. J. Glob. Optim. 11, 341–359 (1997).

Rocca, P., Oliveri, G. & Massa, A. Differential evolution as applied to electromagnetics. IEEE Antennas Propag. Mag. 53(1), 38–49 (2011).

Chakraborty, U. K. Advances in Differential Evolution. 143. Springer Science & Business Media (2008).

Kuhn, M. & Johnson, K. Applied Predictive Modeling. Vol. 26. Springer (2013).

Kuhn, M., et al. Cubist models for regression. R package Vignette R package version 0.0 18, 480 (2012).

Geurts, P., Ernst, D. & Wehenkel, L. Extremely randomized trees. Mach. Learn. 63(1), 3–42 (2006).

Cutler, A., Cutler, D. R. & Stevens, J. R. Random forests. Ensemble machine learning: Methods and applications 157–175 (2012).

Sumayli, A., Mahdi, W. A. & Alamoudi, J. A. Analysis of nanomedicine production via green processing: Modeling and simulation of pharmaceutical solubility using artificial intelligence. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 51, 103587 (2023).

Wehenkel, L., Ernst, D. & Geurts, P. Ensembles of extremely randomized trees and some generic applications. in Robust Methods for Power System State Estimation and Load Forecasting (2006).

Meddage, D., et al. Tree-based regression models for predicting external wind pressure of a building with an unconventional configuration. in 2021 Moratuwa Engineering Research Conference (MERCon). IEEE (2021).

Fafalios, S., Charonyktakis, P., & Tsamardinos, I. Gradient boosting trees. Gnosis Data Analysis PC 1 (2020).

He, Z., et al. Gradient boosting machine: a survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.06951 (2019).

Brownlee, J. XGBoost with python: Gradient boosted trees with XGBoost and scikit-learn Machine Learning Mastery (2016).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining (2016).

Dong, J. et al. A neural network boosting regression model based on XGBoost. Appl. Soft Comput. 125, 109067 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2025R516) at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

This work was supported by the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2025R516), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Adel Alhowyan: Conceptualization, Writing, Methodology, Formal analysis. Wael A. Mahdi: Resources, Writing, Investigation, Validation. Ahmad J. Obaidullah: Conceptualization, Resources, Visualization, Investigation, Writing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alhowyan, A., Mahdi, W.A. & Obaidullah, A.J. Computational intelligence investigations on evaluation of salicylic acid solubility in various solvents at different temperatures. Sci Rep 15, 7142 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90704-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90704-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Advanced analysis on the correlation of salicylic acid solubility to solvent composition, temperature and pressure via machine learning approach

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Development of several machine learning based models for determination of small molecule pharmaceutical solubility in binary solvents at different temperatures

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Analysis of drug crystallization by evaluation of pharmaceutical solubility in various solvents by optimization of artificial intelligence models

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Machine learning analysis of pharmaceutical cocrystals solubility parameters in enhancing the drug properties for advanced pharmaceutical manufacturing

Scientific Reports (2025)