Abstract

Text classification is an important task in the field of natural language processing, aiming to automatically assign text data to predefined categories. The BertGCN model combines the advantages from both BERT and GCN, enabling it to effectively handle text data for classification. However, there are still some limitations when it comes to handling complex text classification tasks. BERT processes sequence information in segments and cannot directly capture long-distance dependencies across segments, which is a limitation when dealing with long sequences. GCN tends to suffer from over-smoothing problem in deep networks, leading to information loss. To overcome these limitations, we propose the XLG-Net model, which integrates XLNet and GCNII to enhance text classification performance. XLNet employs permutation language modeling and improvements of the Transformer-XL architecture, not only improving the ability to capture long-distance dependencies but also enhancing the model’s understanding of complex language structures. Additionally, we introduce GCNII to overcome the over-smoothing problem in GCN. GCNII effectively retains the initial features of nodes by incorporating initial residual connections and identity mapping mechanisms, ensuring effective information transmission even in deep networks. Furthermore, to achieve excellent performance on both long and short texts, we apply the design philosophy of DoubleMix to the XLNet model, using a hybrid approach of mixing hidden states improves the model’s accuracy and robustness. Experimental results demonstrate that the XLG-Net model achieves significant performance improvements on four benchmark text classification datasets, validating the model’s effectiveness on complex text classification tasks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Text classification1 is one of the fundamental tasks in the field of natural language processing (NLP), aiming to automatically categorize text based on its content. It significantly enhances the efficiency of organizing, retrieving, and understanding text, making it easier for people to extract the required information from large volumes of text data. As an important technology, text classification has been successfully applied in various fields. For example, in sentiment analysis2, it helps identify users’ emotional tendencies towards a product or service. In information retrieval3, text classification aids in the effective filtering and sorting of vast amounts of information. In opinion mining4, it enables the identification and analysis of public opinions and attitudes towards a specific topic or event.

Traditional text classification methods include machine learning techniques5,6,7 and deep learning approaches8,9,10. Machine learning methods rely on handcrafted features, representing text by statistically analyzing word frequencies and co-occurrence relationships. Deep learning methods automatically learn complex feature representations from text using neural network models, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs). However, these traditional methods struggle to capture the complex relationships and structural information in texts, such as dependencies between words, and perform poorly in handling long-distance dependencies.

To address these issues, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)11,12 have been widely used in text classification tasks. Yao et al.13 proposed TextGCN, which transformed the text classification problems into node classification issues using graph convolutional networks. Huang et al.14 improved TextGCN by introducing a message-passing mechanisms and reducing memory consumption. Zhang et al. proposed TextING15, which enhanced the model’s generalization ability by constructing relationships between words. Tayal et al.16 extended graph convolutional networks by incorporating label dependencies in the output space. Wang et al.17 proposed two different graph construction methods to capture sparse semantic relationships between short texts. Song et al.18 leveraged corpus graphs and sentence graphs for text classification. Li et al.19 used semantic feature graphs to represent text semantics and proposed a semantic information transfer mechanism to transfer contextual semantic information. Although GNNs can consider both local and global structural features of the original data in text classification, the lack of rich contextual representation for nodes leads to slower convergence and lower accuracy.

In recent years, pre-trained models have achieved notable success in text classification tasks. For example, Word2Vec20 enabled the conversion of large-scale words into word vectors. Transformer21 utilized attention mechanisms to capture intrinsic relationships in data. BERT22 uses a bidirectional pre-trained model to extract more information and achieve more accurate semantic understanding. Pre-trained models learn the features and patterns of data by being pre-trained on large-scale datasets. These models typically use unsupervised learning methods to train on unlabeled data, learning a general form of data representation. This significantly enhances the performance of models in text classification tasks. However, pre-trained models primarily rely on sequential data to establish relationships between words, which often overlooks structural information, making it challenging to capture both local and global structural features.

To combine the advantages of pre-trained models and GNNs, several studies have been proposed. Yang et al.23 proposed the BEGNN model, which constructs text graph based on word co-occurrence relationships and uses GNNs to extract text features. Lv et al.24 proposed the RB-GAT model, which achieves text classification by combining RoBERTa25, BiGRU26 and Graph Attention Network (GAT)27. Lin et al.28 proposed BertGCN model for text classification, which constructs a heterogeneous graph for the corpus and utilizes BERT to initialize document nodes, then performs convolution operations using GCN29. By jointly training the BERT and GCN module, the model can better capture semantic information and word dependencies in the text, making it perform well on many text classification datasets.

However, despite the success of BertGCN in text classification, it still has some limitations. Although BERT can capture bidirectional contextual information, it randomly masks some words during training, resulting in a pretrain-finetune discrepancy. Additionally, BERT processes sequence information into segments, which limits the model’s ability to handle long sequences. Moreover, Li et al.30 and Xu et al.31 pointed out that GCN suffers from an over-smoothing problem, as the number of layers increases, the representations of different nodes become too similar, leading to information loss and performance degradation. To address these issues, we propose a new model, XLG-Net. In this model, XLNet32 uses an autoregressive approach for pre-training. This approach avoids the inconsistencies caused by masked language models and better captures contextual information through a two-stream attention mechanism. GCNII33 alleviates the over-smoothing problem by introducing initial residuals and identity mapping34. Finally, we incorporate the design philosophy of DoubleMix35 into the model, hybridizing the model’s hidden states, effectively enhancing its performance in handling both long and short texts.

Specifically, our contributions are as follows:

-

1.

We propose a novel hybrid architecture, XLG-Net. Our proposed model uses the XLNetMix module and a deep GCNII module to extract text features. It captures contextual information more effectively while considering the structural information of the text, enabling precise text representation and significantly improving classification accuracy.

-

2.

We incorporate the design philosophy of DoubleMix to XLNet by mixing the hidden states in the model. By learning from the hidden states obtained from both the original and augmented data, the model obtains better feature representation for text data, enhancing accuracy and robustness.

-

3.

Our method outperforms other baseline models on four benchmark text classification datasets. Through experiments and analysis, we demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach.

Related work

Pre-training model

In the field of NLP, pre-trained models36 can be divided into two categories. The first type mainly learns shallow word embeddings, such as Word2Vec20 and GloVe37. Although they can generate high-quality word vectors, these pre-trained word vectors cannot dynamically change with context, making it difficult to understand higher-level text concepts. The second type of model primarily learns contextual embeddings, where the semantic information of words changes with the context. For example, the ELMo38 model, which is based on bidirectional LSTM39, addresses the polysemy problem, resulting in word vectors that can vary with the context. The ULMFiT40 model achieves optimal results in text classification tasks by fine-tuning pre-trained models, solving the problem of needing to train models from scratch each time. Vaswani et al.21 proposed the new Transformer architecture, which innovatively advanced the attention mechanism41, enhancing the ability of parallel computing and enabling the model to learn more data features in a short time. Inspired by Transformer, the GPT model42 was proposed, which uses a unidirectional Transformer to replace the LSTM of ELMo for pre-training tasks. This was the first pre-trained model to incorporate the Transformer architecture. Devlin et al.22 introduced the BERT pre-trained model, which employs a bidirectional Transformer for pre-training, enabling better utilization of bidirectional contextual information. BERT broke 11 NLP task records, including raising the GLUE benchmark to 80.4%, achieving an accuracy of 86.7% on MultiNLI(an absolute improvement of 5.6%), and raising the SQuAD v1.1 question-answering test F1 score to 93.2. The RoBERTa25 model is a fine-tuned version of BERT, which meticulously analyzes BERT’s hyperparameters and makes minor modifications to enhance the model’s representation ability. ALBERT43 is one of the classic variants of BERT, which significantly reduces the number of parameters while maintaining performance. XLNet14 integrates some important ideas from Transformer-XL44 into pre-training. For example, by introducing segmented linear positional encoding, it can handle long texts more effectively. Additionally, XLNet increased the scale of data used during pre-training, surpassing BERT on 20 tasks and achieving state-of-the-art performance on 18 tasks.

Graph neural network

In recent years, GNNs have received widespread attention for their ability to extract and integrate features from multi-scale local spatial data, demonstrating strong representational abilities. They have successfully extended deep learning models from Euclidean to non-Euclidean spaces. In graphs, there are not only node features but also structural features. GNNs capture dependencies and relationships between nodes through messages passed along edges. GCN was the first to simply apply the convolution operation in image processing to graph structured data. The main idea is to calculate the weighted average of a node’s neighbors and its own information, thereby obtaining a feature vector that can be fed into a neural network. Veličković et al.27 proposed the GAT, which uses an attention mechanism to compute the attention weights of each node with respect to its neighboring nodes, enhancing the model’s robustness and interpretability. Hamilton et al.45 introduced GraphSAGE, which uses a sampling mechanism to overcome the issues of high memory consumption and slow computation when gradient updating on large-scale graphs.

Despite the significant achievements of GCN and its variants, most of these models are shallow. For example, the optimal models for GCN and GAT are typically two-layer networks. Theoretically, too few layers limits the model’s ability to capture higher-order neighbor information. However, when the number of layers is too high, these models suffer from a degradation in learning ability, such a phenomenon is called over-smoothing. Chen et al.33 proposed the GCNII model, which incorporates residual connections and identity mapping into GCNs to address the over-smoothing issue, thereby ensuring that deeper GCNII model can achieve at least the same performance as their shallow counterparts.

The fusion of pre-trained models and graph neural networks

After the success of pre-trained models and GNNs, some researchers proposed combining these two approaches. Lu et al.46 proposed VGCN-BERT, which integrates the BERT model with a Vocabulary Graph Convolutional Network (VGCN) to capture both local and global information of the data. Graph-Bert47 decomposes the graph into subgraphs to learn the feature information of each node and improves the efficiency of the model through parallel processing. Lin et al.28 proposed BertGCN, a text classification model that combines pre-trained models with transductive learning. It employs techniques such as prediction interpolation, memory storage, and small learning rates during training, achieving significant performance improvements on five text classification datasets. ViCGCN48 leverages the complementary strengths of pretrained models and graph GCN to capture more syntactic and semantic information, addressing the issues of data imbalance and noise in Vietnamese social media texts.

Method

In this part, we describe the structure of XLG-Net in detail.

Architecture overview

In the proposed XLG-Net model, the model structure is shown in Fig. 1, we have designed four modules: (1) graph construction; (2) feature extraction based on XLNetMix; (3) feature extraction based on GCNII; and (4) feature aggregation. The construction module of the graph, namely the Heterogeneous Graph section in Fig. 1, for each dataset, we constructed a heterogeneous graph in accordance with the importance and relevance of its documents and words. The specific methodology is expounded in the section titled “Graph construction”. The XLNetMix module is utilized to process the input text. The features with contextual representations extracted by it are used, on the one hand, to initialize the embedding representations of the document nodes in the heterogeneous graph, and on the other hand, for the subsequent feature fusion module. The heterogeneous graph initialized by the XLNetMix module will be input into the GCNII module. The GCNII applies graph convolution operations to aggregate the information of surrounding words in the sentence. The specific details are explained in the section titled “GCNII based feature extraction”. Finally, the prediction of GCNII and that of the XLNetMix module are fused to obtain the ultimate prediction result.

Graph construction

We construct a heterogeneous graph for each dataset, denoted as \(G=\left( V,E \right)\), where \(V\) is the set of all nodes in the graph and \(E\) is the set of edges between nodes, as shown in Fig. 2.

Following the rules of TextGCN, we divide the nodes into document nodes and word nodes. The connections between word nodes and document nodes are measured using term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF). The connections between word nodes are measured using positive pointwise mutual information (PMI). The weight of the edge connecting nodes \(i\) and \(j\) is calculated by Eq. (1):

The PMI value of a word pair \(i\), \(j\) is calculated by Eqs. (2)(3)(4):

Where, \(\#W\left( i,j \right)\) is the number of sliding windows that contain word \(i\) and word \(j\), and \(\#W\left( i \right)\) is the number of sliding windows that contain word \(i\). \(\#W\) is the total number of sliding windows.

Similarly, we use an identity matrix \(X=I_{n_{\text {doc}}+n_{\text {word}}}\) as the initial features of the nodes, where \(n_{\text {doc}}\) represents the number of document nodes and \(n_{\text {word}}\) represents the number of word nodes. In the XLG-Net model, we use the XLNetMix model to extract feature from the text data, and use them as input representations for document nodes. The embedding of the document nodes is denoted as \(X_{\text {doc}}\in \mathbb {R}^{n_{\text {doc}}\times d}\), where \(d\) is the dimension of the embedding. Consequently, the initial feature matrix of the nodes can be represented as Eq. (5):

Algorithm 1 outlines the steps for constructing a heterogeneous graph.

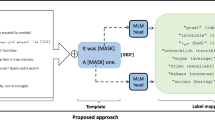

XLNetMix based feature extraction

In this section, we introduce the structure of XLNetMix. The input of XLNetMix is sample data, and its output is the contextualized word embedding that encompasses entire information of input sequence. The overview of XLNetMix architecture is shown in Fig. 3.

In order to improve the robustness of the model, we perform two back-translation operations on each dataset to get two perturbed samples. Based on the idea of DoubleMix, we perform the mixing operation in the hidden space of XLNet. As shown in Fig. 3, we use the XLNet pre-trained model with \(L\) layer. Firstly, we fed both original samples and two perturbed samples to the XLNet layer, then we use the \(i\)-th layer in [0, \(L\)] as the mixing layer to perform the two-step interpolation operation. The first step is to mix up the two perturbed samples by sampling a group of weights from the Dirichlet distribution, and the second step is to mix up the synthesized perturbed sample with the original sample by sampling weights ranging from 0 to 1 derived from the Beta distribution. Since the generated perturbation samples may contain potential injected noise, when mixing the original data and the synthesized perturbation data, we constrain the weight of the original data to a larger value to balance the appropriate trade-off between perturbation and noise, making the final representation closer to the original representation. The feature representations output by the last layer of the model are used as input representations for the document nodes, and then these contextual embedding representations are fed to the GCNII layer.

GCNII based feature extraction

For heterogeneous graph \(G\), we use GCNII for feature extraction and propagation. Each layer of GCNII is defined as Eq. (6):

Where \(H^{\left( 0 \right) }\) represents the feature representation of \(0\)-th layer, \(\alpha _{\ell }\) and \(\beta _{\ell }\) are two hyperparameters, and \(\tilde{P}=\tilde{D}^{-\frac{1}{2}}\tilde{A}\tilde{D}^{-\frac{1}{2}}\) is the graph convolution matrix49. Residual connection have always been one of the most commonly used techniques to alleviate over-smoothing problem. However, GCNII does not obtain information from the previous layer. Instead, it performs a residual connections from the initial layer, linking the smoothed node representation \(\tilde{P}H^{\left( l \right) }\) with the initial layer \(H^{\left( 0 \right) }\) through residual connections and assigning it a weight \(\alpha _{\ell }\), which is the first part of the Eq. (6). The initial layer \(H^{\left( 0 \right) }\) is not the original input feature, but is obtained by applying a linear transformation \(H^{\left( 0 \right) }\;=\;f_{\theta }\left( X \right)\) to the input features. Using residuals alone can only alleviate the problem of over-smoothing, therefore, GCNII incorporates the idea of identity mapping from ResNet, that is, adding an identity matrix \(I_n\) to the weight matrix \(W^{\left( l \right) }\) and setting a weight \(\beta _{\ell }\).

Overall, the concept of initial residuals is to select weights between the current layer representation and the initial layer representation, while identity mapping is to select weights between parameter \(W^{\left( l \right) }\) and the identity matrix \(I_n\). The output of GCNII is the updated feature representation, denote as \(Z_{\text {GCNII}}\), which captures the structural information of the document and obtains the final prediction through the \(softmax\) layer, as shown in Eq. (7):

Where \(g\) denotes the GCNII model, \(X\) is the input feature matrix, \(A\) is the normalized adjacency matrix.

Joint XLNetMix and GCNII predictions

Through preliminary experiments, we find that adding an auxiliary classifier to XLG-Net and directly using the document embeddings generated by XLNetMix as input leads to faster convergence and better performance. Specifically, we construct the auxiliary classifier by feeding the document embeddings into a dense layer with \(softmax\) activation, as shown in Eq. (8):

Where \(X\) represents document embeddings and \(W\) represents the weight matrix.

Specifically, we propose using \(\lambda\) to control the trade-off between XLNetMix predictions and GCNII predictions to optimize the XLG-Net model. We implement this using the following Eq. (9):

In section of Hyper-Parameter settings, we conduct comprehensive experiments on four datasets to determine the optimal value of \(\lambda\). XLNetMix can capture contextual relationships within documents and GCNII can capture dependencies between semantic relationships. The combination of these two abilities can improved performance on tasks that require understanding the semantic relationships between words.

Experiments and analysis

Datasets

We conducted experiments on four widely used text classification datasets: Movie Review (MR), Ohsumed, R52 and R8. The summary statistics of the datasets is presented in Table 1:

-

(1)

Movie Review (MR). It is a sentiment classification dataset containing 10,662 movie reviews, each of which can be judged as positive or negative. Specifically, 5331 reviews are positive, and 5331 reviews are negative. In our experiments, 7108 documents of this dataset were employed as the training set and 3554 documents as the test set.

-

(2)

Ohsumed. The dataset is sourced from the MEDLINE database, a significant bibliographic database of medical literature maintained by the National Library of Medicine. It contains 7400 documents with medical abstracts covering 23 categories of cardiovascular diseases. In this study, 3357 documents were used as the training set, and 4043 documents were used as the test set.

-

(3)

R52 and R8. They are two subsets of the Reuters 21,578 dataset. The R52 subset encompasses 52 categories, with 6532 training documents and 2568 test documents. The R8 subset contains 8 categories, divided into 5485 training documents and 2189 test documents.

Baselines

In order to comprehensively evaluate the proposed method, we compare XLG-Net with several widely recognized text classification models with good performance, including deep models for serialized data processing and models based on GNNs.

BERT22. It is a pre-trained language representation model introduced by Google in 2018. By pre-training on a vast corpus of text data, it acquires a deep understanding of textual semantics. The core of the BERT model is the Transformer architecture, which employs a bidirectional attention mechanism to capture long-distance dependencies within the text. BERT has achieved revolutionary results in multiple tasks of NLP, such as text classification, question-answering systems, and named entity recognition. Its bidirectional training approach enables the model to better comprehend contextual information, thereby excelling in a variety of language understanding tasks.

XLNet32. It is designed to address some of the limitations inherent in traditional language models and the BERT model when processing language. The core contribution of XLNet lies in its adoption of a novel pretraining objective known as Permutation Language Modeling (PLM). By considering all possible permutations of words in a sequence, it captures the interdependencies among different words, thereby more effectively modeling bidirectional context information. Furthermore, XLNet employs a dual-stream self-attention mechanism that achieves target position awareness through the self-attention of content and query streams, thus taking positional information into account during prediction.

SGC50. The SGC (Simple Graph Convolution) model is a simplified version of the graph convolutional network. It simplifies a multi-layer graph convolutional network into a linear model by eliminating the non-linear activation functions between GCN layers. This approach reduces the complexity and computational load of the model while maintaining performance comparable to the original GCN on multiple tasks. The core idea of the SGC model is that the non-linear activation functions in graph convolutional networks are not the key factors in improving performance, the operation of averaging local neighbor features is more critical. Therefore, the SGC model simplifies the model structure by removing these non-linear activation functions and retaining only the final softmax function for classification. In SGC, feature extraction is equivalent to applying a fixed filter on each feature dimension.

TextGCN13. It is a text classification method based on GCN. Its core concept involves leveraging the co-occurrence relationships among words in the text and the relationships between documents and words to construct a graph, where documents and words serve as the nodes of the graph. If a word appears in a document, there will be an edge between these two nodes. The weight of the edges can be represented using TF-IDF to signify the relationship between documents and words. The relationships between word nodes can be constructed through PMI, reflecting the co-occurrence relationships among words. Through the graph convolutional network, TextGCN is capable of learning the embedded representations of documents and words, which can then be utilized for text classification tasks.

TextING15. It is a text classification tool based on GNNs, which enhances feature representation by constructing a semantic graph spectrum of documents, thereby improving the accuracy and generalization ability of classification. The core advantage of TextING lies in its ability to capture the structural information within documents and achieve hierarchical feature extraction through the iterative propagation of graph neural networks. It is suitable for various application scenarios, including news topic classification, sentiment analysis and professional document archiving.

GLTC51. This model is devised with two feature extractors for the purpose of capturing the structural and semantic information within the text. Moreover, the KL divergence is incorporated as a regularization term during the loss calculation process.

RB-GAT52. It is an innovative text classification model that integrates various advanced technologies such as RoBERTa, BiGRU, and GAT. Firstly, it utilizes RoBERTa to extract the initial semantic embeddings of the text. Subsequently, BiGRU further captures the long-distance dependencies and bidirectional information. Then, taking the output of BiGRU as node features, GAT analyzes the semantic structure and key information of the text by employing the multi-head attention mechanism. Finally, the classification results are obtained through the Softmax layer.

BertGCN28. It combines the BERT pre-trained model with GCN to enhance text processing abilities. BertGCN integrates the output of the BERT model as node features in the GCN, enabling the model to handle graph-structured data with text information more effectively. This approach leads to improved performance in text classification tasks.

Experiment setups

Following the approach of TextGCN, we processed all datasets by cleaning and tokenizing the text, then removing some low-frequency words. Finally, we used 10% of the training data for validation to facilitate model training, the model subjected to 50 training iterations. We use XLNetMix and an 8-layer GCNII to implement XLG-Net. Perform two back-translation operations on each dataset to obtain two perturbed samples, and then input both the original samples and the perturbed samples into the XLG-Net model. For the XLNetMix module, we use the output features of the [CLS] token as the document embedding, followed by a feedforward layer to generate the final prediction. At the beginning of each epoch, we use XLNetMix to compute all documents embeddings and update the graph’s node features with these embeddings. The graph is then fed into XLG-Net for training. Therefore, to improve the consistency of the embeddings, we set a smaller learning rate for the XLNetMix module and a larger learning rate for the GCNII module. We compared our research results with previous studies to accurately evaluate our findings. Additionally, to gain a deeper understanding of our proposed model, we conducted an analysis and discussion from various perspectives, including the impact of parameter \(\lambda\) and the number of GCNII layers. Finally, we conducted ablation experiments to validate the effectiveness of our proposed XLG-Net method. All the codes are written using PyTorch and run on a single V100-32GB GPU.

Evaluation metric

This section delineates the performance evaluation criteria adopted in this research. In the domain of classification tasks, particularly with respect to the four datasets accentuated in this study, the commonly utilized metric is Accuracy, which is defined as the ratio of the number of correctly classified texts to the total number of texts. Nonetheless, in light of the pronounced class imbalances inherent in these datasets, the most suitable metric for this research is the Average Macro F1-score, which is computed as the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall.

To determine the Average Macro F1-score, we initially compute Precision and Recall for each class using Eqs. (10) and (11), respectively. Subsequently, Eq. (12) is applied to ascertain the F1-score for each individual class within the dataset. Here, \(TP\) denotes the count of true positives, \(FP\) the count of false positives, \(FN\) the count of false negatives, and \(TN\) the count of true negatives.

Upon obtaining the F1 scores for all classes, we calculate the average macro F1-score (mF1). Eq. (13) depict the macro F1-score in the context of multi-class classification for multiple classes \(C_i\),\(i\in \{1,2,\ldots n\}\)(representing each class within the dataset). In these equations, \(F1\text {-}s c o r e_i\) denote the \(F1\text {-}s c o r e\) of class \(i\) of the dataset.

Overall results

To verify the performance of the XLG-Net model in text classification, we made a comparison between it and the previous studies, specifically the baselines enumerated in the section titled “Baselines”. The Accuracy and Macro-average F1 of different models on four text classification datasets are presented in Tables 2 and 3:

As can be observed from Tables 2 and 3, XLG-Net attains the optimal performance across the four datasets. Among all the models under consideration, SGC and TextGCN demonstrate the least favorable performance throughout the four datasets. Furthermore, BERT and XLNet surpass SGC, TextGCN, and TextING, thereby highlighting the advantage of pre-trained models. BertGCN and XLG-Net outstrip other models by a substantial margin, which can be ascribed to the integration of pre-trained models and GCN models, allowing them to complement each other’s strengths. In comparison to BERT and XLNet, XLG-Net exhibits significant enhancements on the Ohsumed dataset. This is attributable to the fact that the average text length of Ohsumed is 79, which is longer than that of other datasets. Since the graph is constructed based on document-word statistics, it implies that the graph derived from longer texts possesses a more complex structure. Such complexity facilitates more effective message propagation, thus enabling the models to achieve superior performance. XLG-Net outperforms the BertGCN model on the four datasets. This can be accounted for by XLNet’s proficiency in capturing long sequential dependencies and GCNII’s capacity to efficiently transfer information within deep networks. Additionally, the incorporation of the design philosophy of DoubleMix in the XLG-Net model empowers it to perform well on short-text datasets as well, which elucidates why XLG-Net shows significant improvements over BertGCN on the MR dataset.

Hyper-parameter settings

The configuration of hyperparameters within the neural network exerts a significant impact on the ultimate experimental outcomes. In order to further enhance the performance of the XLG-Net model, an in-depth exploration is conducted regarding the different hyperparameters.

The effect of \(\lambda\)

In accordance with Eq. (9), the hyperparameter \(\lambda\) governs the balance between the output features of XLG-Net and those of XLNetMix, and its value directly dictates the accuracy of the final outcomes. Consequently, we carried out experiments on four benchmark datasets with the aim of determining the optimal value of \(\lambda\).

Figure 4 presents the accuracy of XLG-Net with varying \(\lambda\) values on the MR, Ohsumed and R52 datasets. It can be observed that, on these four benchmark datasets, setting the value of \(\lambda\) within the range of 0.6 to 0.8 is the most suitable, and the accuracy attains its optimum when \(\lambda\) is 0.6. Moreover, when \(\lambda\) = 1(utilizing only XLG-Net), the accuracy is consistently higher than when \(\lambda\) (employing only XLNetMix). These results demonstrate that the predictions of XLG-Net are more accurate in text classification tasks when \(\lambda\) is larger. On the other hand, the XLNetMix module is also essential. The appropriate adjustment of the proportion of predictions made by the XLNetMix module can exert a positive influence on the performance of the model.

The effect of \(L\)

In typical graph node classification or graph classification tasks, classic GNN models such as GCN and GAT can achieve good performance with 2–4 layers. Adding more layers often leads to over-smoothing. GCNII addresses this issue, allowing the model’s performance to improve even with a large number of layers. Therefore, exploring the optimal number of GCNII layers(\(L\)) in XLG-Net is also important. We conducted experiments on four benchmark datasets to determin the optimal value of \(L\) and the results are shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5 shows the accuracy of XLG-Net with different \(L\) values on the MR, Ohsumed, and R52 datasets, respectively, we can see that when the value of \(L\) is less than 8, the larger the value of \(L\), the higher the model’s accuracy. When \(L\) = 8, the model reaches its best. When L exceeds 8, the model’s predictive accuracy exhibits a gradual decline, indicating that a larger value of L is not necessarily better. Furthermore, the model’s performance on the MR dataset is more susceptible to the influence of L, with the predictive accuracy undergoing significant fluctuations as L varies.

The effect of other parameters

For a more thorough exploration of the performance of the XLG-Net model, further investigations were conducted with respect to the learning rate and the number of hidden layers. The value of \(\lambda\) was configured to be 0.6, and the number of GCNII layers was set to 8, while the remaining parameters remained unchanged. Multiple rounds of experimental evaluations were performed for all parameters, and the average results are presented as follows.

The learning rate represents a vital hyperparameter within the realms of supervised learning and deep learning. It governs the capacity of the objective function to converge to a local minimum and the temporal aspect of such convergence. In cases where the learning rate is excessively high, the loss function might overshoot the global optimum directly. Conversely, an overly low learning rate leads to a sluggish rate of change in the loss function, rendering it susceptible to becoming entrapped in a local minimum. Tables 4 and 5 present the comparative outcomes of two learning rates. It is discernible that as the learning rate diminishes, the F1 value of the model initially ascends and subsequently descends. When the learning rate of XLNetMix is configured at 0.000007 and that of GCNII is set to 0.0007, the model attains the peak F1 value. These particular values are thus elected for experimentation within the XLG-Net model.

The dimensionality of the hidden layers in GCNII dictates the number and complexity of features that the model can learn. Consequently, selecting an appropriate dimensionality size significantly impacts the model’s performance, complexity, and generalization capabilities. Table 6 illustrates the impact of varying the dimensions of the hidden layer in GCNII on the classification results. When the number of hidden layers was increased to 256, the classification performance declined significantly. This was because the increase in hidden layers introduced more parameters and computations, which impaired the model’s fitting.

Ablation study

Effect of interpolation layers

The hidden layers in pre-trained models are powerful in representation learning. In order to investigate the contribution of interpolation operations in the hidden layer to the model, we conducted ablation experiments. Specifically, we set the number of XLNet layers \(L\) in the model to 12, and conducted experiments by group interpolation. The results are shown in Table 7.

When all interpolations were excluded, the accuracies on the four datasets were 87.03%, 72.66% , 96.44% and 98.29%. When we perform interpolation at layer 1, the accuracy improves by 1.26%, 0.26% , 0.02% and 0.04%. It shows that the idea of DoubleMix is also applicable in XLNet and contributes to the improvement of model performance. When we interpolate at layer set {1, 2}, the accuracy improvement of the model is small. However, when we interpolate at layer sets {3, 4, 5} and {5, 6}, the performance improvement is significant. According to Jawahar et al.53, the hidden layers {3, 4} of BERT perform best in encoding surface features, layers {6, 7, 9, 12} contain the most syntactic features and semantic features, while the 9-th layer captures the most of syntactic and semantic information. Therefore, we have tried several layer sets containing the 9-th layer and find that the {9, 10, 12} layer set has the best performance on all four datasets. In addition, we notice that the number of layers in the interpolation layer set is not the more the better. The layer set {3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 12} gives a low improvement in accuracy, indicating that too many interpolated layers will reduce the performance.

Effectiveness of XLNet and GCNII

To investigate the contributions of XLNet and GCNII to the model, we explored the performance of the model when replacing the BERT layers with XLNet layers and when replacing the GCN layers with GCNII layers, based on the BertGCN architecture. The results are shown in Fig. 6.

From Fig. 6, we can observe that XLNet+GCNII (the combination of XLNet and GCNII) achieved the best performance. XLNet+GCN (the combination of XLNet and GCN) resulted in improved performance on the MR and Ohsumed datasets compared to BertGCN. BERT+GCNII (the combination of BERT and GCNII) resulted in improvements on four datasets compared to BertGCN. When both modules were replaced (XLNet+GCNII), there was a further performance boost on the MR and Ohsumed datasets, as well as a slight improvement on the R52 dataset. In summary, the combined use of XLNet and GCNII has demonstrated outstanding performance in enhancing model accuracy, particularly on the MR and Ohsumed datasets.

Conclusion and future work

In this research endeavor, we put forward a novel method named XLG-Net, which capitalizes on the potent contextual word representations furnished by large-scale pre-trained models and the profound graph convolutional techniques of GCNII for the purpose of text classification. We blend the hidden states of the XLNet model to enhance both the accuracy and robustness of the model. We conducted multiple experiments and compared the XLG-Net with several benchmark models. The experimental results demonstrated that on four benchmark text classification datasets, the XLG-Net outperformed the BertGCN model as well as other benchmark models. In addition, we also delved into the impact of different hyperparameter settings on the model’s performance, thereby further validating the effectiveness of the proposed method.

Nevertheless, within this work, it remains necessary for us to construct the heterogeneous graph of the entire dataset prior to employing the model to extract features. This methodology might be less than optimal when compared to models capable of automatically constructing graphs. Meanwhile, as the number of layers in the GCNII model increases, although the model performance is improved, the model training time becomes longer as well. At this point, optimizing the model structure to accelerate the training efficiency should be taken into consideration. Furthermore, due to limitations in computing power, we only tested the experimental results of the GCNII model with the number of layers less than 16. If the number of layers exceeds 16, the performance of the model might be improved. These issues will be left for future exploration.

Data availability

The MR dataset generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the https://www.cs.cornell.edu/people/pabo/movie-review-data. The Ohsumed datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the https://disi.unitn.it/moschitti/corpora.htm. The R52 dataset generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the https://huggingface.co/datasets/mingi-sid/r52-raw. The datasets generated in the current study are not publicly available due ongoing research but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Minaee, S. et al. Deep learning-based text classification: a comprehensive review. ACM Comput. Surveys (CSUR) 54, 1–40 (2021).

Zhang, C., Li, Q. & Song, D. Aspect-based sentiment classification with aspect-specific graph convolutional networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.03477 (2019).

Xiao, S. et al. Progressively optimized bi-granular document representation for scalable embedding based retrieval. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2022, 286–296 (2022).

Pang, B. et al. Opinion mining and sentiment analysis. Found. Trends Inf. Retr. 2, 1–135 (2008).

Kim, H., Howland, P., Park, H. & Christianini, N. Dimension reduction in text classification with support vector machines. Journal of machine learning research6 (2005).

Fernández, J., Montañés, E., Díaz, I., Ranilla, J. & Combarro, E. F. Text categorization by a machine-learning-based term selection. In Database and Expert Systems Applications: 15th International Conference, DEXA 2004, Zaragoza, Spain, August 30-September 3, 2004. Proceedings 15, 253–262 (Springer, 2004).

Mladenić, D., Brank, J., Grobelnik, M. & Milic-Frayling, N. Feature selection using linear classifier weights: interaction with classification models. In Proceedings of the 27th annual international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in information retrieval, 234–241 (2004).

Tang, D., Qin, B. & Liu, T. Document modeling with gated recurrent neural network for sentiment classification. In Proceedings of the 2015 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing, 1422–1432 (2015).

Lai, S., Xu, L., Liu, K. & Zhao, J. Recurrent convolutional neural networks for text classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, vol. 29 (2015).

Yang, Z. et al. Hierarchical attention networks for document classification. In Proceedings of the 2016 conference of the North American chapter of the association for computational linguistics: human language technologies, 1480–1489 (2016).

Wu, Z. et al. A comprehensive survey on graph neural networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks Learning Syst. 32, 4–24 (2020).

Zhou, J. et al. Graph neural networks: A review of methods and applications. AI open 1, 57–81 (2020).

Yao, L., Mao, C. & Luo, Y. Graph convolutional networks for text classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence 33, 7370–7377 (2019).

Huang, L., Ma, D., Li, S., Zhang, X. & Wang, H. Text level graph neural network for text classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.02356 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Every document owns its structure: Inductive text classification via graph neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.13826 (2020).

Tayal, K. et al. Regularized graph convolutional networks for short text classification. In 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, COLING 2020, 236–242 (Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), 2020).

Wang, Y., Wang, S., Yao, Q. & Dou, D. Hierarchical heterogeneous graph representation learning for short text classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2111.00180 (2021).

Song, R., Giunchiglia, F., Zhao, K., Tian, M. & Xu, H. Graph topology enhancement for text classification. Appl. Intell. 52, 15091–15104 (2022).

Li, Y., Liu, Y., Zhu, Z. & Liu, P. Exploring semantic awareness via graph representation for text classification. Appl. Intell. 53, 2088–2097 (2023).

Mikolov, T., Chen, K., Corrado, G. & Dean, J. Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. arXiv preprint arXiv:1301.3781 (2013).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems30 (2017).

Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K. & Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805 (2018).

Yang, Y. & Cui, X. Bert-enhanced text graph neural network for classification. Entropy 23, 1536 (2021).

Lv, S., Dong, J., Wang, C., Wang, X. & Bao, Z. Rb-gat: A text classification model based on roberta-bigru with graph attention network. Sensors 24, 3365 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.11692 (2019).

Zhang, D. et al. Combining convolution neural network and bidirectional gated recurrent unit for sentence semantic classification. IEEE Access 6, 73750–73759 (2018).

Veličković, P. et al. Graph attention networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.10903 (2017).

Lin, Y. et al. Bertgcn: Transductive text classification by combining gcn and bert. arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.05727 (2021).

Kipf, T. N. & Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.02907 (2016).

Li, Q., Han, Z. & Wu, X.-M. Deeper insights into graph convolutional networks for semi-supervised learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, vol. 32 (2018).

Xu, K. et al. Representation learning on graphs with jumping knowledge networks. In International conference on machine learning, 5453–5462 (PMLR, 2018).

Yang, Z. et al. Xlnet: Generalized autoregressive pretraining for language understanding. Advances in neural information processing systems32 (2019).

Chen, M., Wei, Z., Huang, Z., Ding, B. & Li, Y. Simple and deep graph convolutional networks. In International conference on machine learning, 1725–1735 (PMLR, 2020).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 770–778 (2016).

Chen, H., Han, W., Yang, D. & Poria, S. Doublemix: Simple interpolation-based data augmentation for text classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.05297 (2022).

Qiu, X. et al. Pre-trained models for natural language processing: A survey. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 63, 1872–1897 (2020).

Pennington, J., Socher, R. & Manning, C. D. Glove: Global vectors for word representation. In Proceedings of the 2014 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing (EMNLP), 1532–1543 (2014).

Peters, M. E. et al. Deep contextualized word representations. arxiv: 1802.05365. arXiv (2018).

Graves, A. & Graves, A. Long short-term memory. Supervised sequence labelling with recurrent neural networks 37–45 (2012).

Howard, J. & Ruder, S. Universal language model fine-tuning for text classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:1801.06146 (2018).

Bahdanau, D., Cho, K. & Bengio, Y. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.0473 (2014).

Yenduri, G. et al. Gpt (generative pre-trained transformer)–a comprehensive review on enabling technologies, potential applications, emerging challenges, and future directions. IEEE Access (2024).

Lan, Z. et al. Albert: A lite bert for self-supervised learning of language representations. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.11942 (2019).

Dai, Z. et al. Transformer-xl: Attentive language models beyond a fixed-length context. arXiv preprint arXiv:1901.02860 (2019).

Hamilton, W., Ying, Z. & Leskovec, J. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. Advances in neural information processing systems30 (2017).

Lu, Z., Du, P. & Nie, J.-Y. Vgcn-bert: augmenting bert with graph embedding for text classification. In Advances in Information Retrieval: 42nd European Conference on IR Research, ECIR 2020, Lisbon, Portugal, April 14–17, 2020, Proceedings, Part I 42, 369–382 (Springer, 2020).

Zhang, J., Zhang, H., Xia, C. & Sun, L. Graph-bert: Only attention is needed for learning graph representations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.05140 (2020).

Phan, C.-T., Nguyen, Q.-N., Dang, C.-T., Do, T.-H. & Van Nguyen, K. Vicgcn: Graph convolutional network with contextualized language models for social media mining in vietnamese. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.02902 (2023).

Kipf, T. N. & Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.02907 (2016).

Wu, F. et al. Simplifying graph convolutional networks. In International conference on machine learning, 6861–6871 (PMLR, 2019).

Yin, S. et al. Integrating information by kullback-leibler constraint for text classification. Neural Comput. Appl. 35, 17521–17535 (2023).

Lv, S., Dong, J., Wang, C., Wang, X. & Bao, Z. Rb-gat: A text classification model based on roberta-bigru with graph attention network. Sensors 24, 3365 (2024).

Jawahar, G., Sagot, B. & Seddah, D. What does bert learn about the structure of language? In ACL 2019-57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (2019).

Funding

This work was supported by the R&D Program of Beijing Municipal Education Commission No.KM202410015002, the Research foundation for Youth Scholars of Beijing Institute of Graphic Communication No.27170123034 and the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Planning Fund of the Ministry of Education of China No.21A10011003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.L.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing - original draft. K.X.: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Z.Q.: Conceptualization, Writing - review. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Q., Xiao, K. & Qian, Z. A hybrid re-fusion model for text classification. Sci Rep 15, 9333 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90864-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90864-w

This article is cited by

-

A novel double and triple BERT and distilBERT classification methods

Neural Computing and Applications (2025)