Abstract

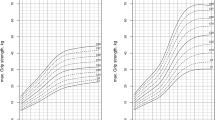

This study was undertaken to establish the UAE population’s normal BMI and HC growth charts. BMI growth charts represent BMI values at each age and gender-specific percentiles. The UAE’s development is unique in its cultural practices and genetic makeup; therefore, extrapolating health determinants from other nations to the UAE is unwise. It is, therefore, essential to have reference growth parameters for the UAE population. In this cross-sectional study, we measured BMI and Head Circumference in 20,998 infants and children, of both sexes, 0–18 years of age from all seven states that make up the United Arab Emirates (UAE), enabling us to construct the BMI and HC charts for the UAE. Using the LMS system BMI and HC charts were created. The prevalence of obesity ranged from 0 to 5.9% in males and from 0.8 to 6.6% in females at different ages. The mean BMI values for each age in both sexes were statistically significantly larger than those obtained in UAE children 30 years ago. Our study provides BMI and head circumference charts tailored to the growth patterns of UAE children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Body Mass Index (BMI) is a widely used tool for assessing weight status and monitoring growth in children and adolescents. BMI growth charts visually represent BMI values relative to age and gender-specific percentiles, allowing healthcare professionals to identify individuals at risk of being underweight, overweight, or obese. While BMI charts are commonly used worldwide, it’s essential to develop charts specific to the population being assessed to account for ethnic and regional variations in growth patterns and body composition. The BMI is currently the best available anthropometrically derived estimate of fatness in children. It has been used to depict fatness both in children and in adults acceptably. However, it does not accurately estimate the fat mass in the body. Body composition can differ in individuals with the same BMI.

With the rising concern over obesity-related health issues globally, understanding BMI trends within specific populations becomes imperative for public health interventions and policy formulations. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has developed immensely both economically and in its urbanisation in the last 50 years1,2. As a result, improvements have occurred in all health indicators, including an increase in life expectancy at birth2. The negative side of this rapid development is the sedentary lifestyle and change in diet leading to an increased incidence and prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCD)3,4. In the UAE according to a 2020 Ministry of Health Bulletin 17.3% of children, aged 5–17 years were obese, and 11.8% of the population aged 20–79 years had diabetes mellitus5. Because of the uniqueness of the trajectory of the development of the UAE in its cultural practices and the genetic makeup of its population, the extrapolation of determinants of health from other nations to the UAE is unwise. It is therefore essential to have standard growth parameters for the UAE population.

Cranial growth and brain development have been examined over the years using a standard procedure of the measurement of head circumference ([HC] or occipitofrontal circumference [OFC])6,7,8. This method of estimating brain development is a quick, simple, and economical screening method and does not expose children to radiation. With this easy method, pathological changes can be detected early. Therefore, it is easy to see the multidisciplinary interest in pediatric cranial circumference and braincase volume. In addition to its importance in the differential diagnosis and therapy decisions for neurosurgical, maxillofacial- and plastic surgery9,10, , it is also interesting to those studying evolution11.

A BMI and HC growth chart was produced in a 1992 cohort1,12, more than 30 years ago, it is now the time to create a new chart reflecting BMI and HC of the current population. We have shown in a recent paper that the heights and weights of children measured in this study are significantly higher in children of all ages than in children measured in 199213. Human growth is associated with complex interactions between genetic and environmental factors. As an example, there was reported an increased body size and body mass index (BMI) in Japanese children, in growth before and after World War II (WW II)14,15.

This study aimed to measure the head circumference and BMI of children from 0 to 18 years of age in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), thereby shedding light on prevalent weight categories and potential health implications, and producing a growth chart for BMI and HC. By examining BMI patterns, this research endeavours to contribute to the broader discourse on public health strategies tailored to the UAE’s unique demographic landscape. This is part of a larger study – United Arab Emirates Multi Centre Growth Study (UAEMCGS) 2 study.

Methods

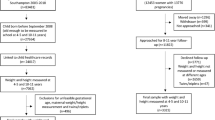

A stratified random sampling technique was employed to ensure the inclusion of participants from different demographic strata, including age, gender, and socioeconomic status. This sample included individuals from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds and all seven Emirates to ensure the charts’ applicability to the entire population. Our measurements were conducted before the onset of the pandemic and during the period 2017/2018, 2018–2019, and 2019–2020. The only measurements made early in the year 2020 were the neonatal data collected from one hospital in Abu Dhabi. Most of the measurements were made in the years 2017 and 2018. This was a cross-sectional study to collect head circumference and BMI measurements from the selected sample of children consisting of preschool-age children [ages of 0 (birth, taken from hospitals), 3 Mo, 6 Mo, 12 Mo, 18 Mo, 24 Mo (from vaccination centres), 3, 4, and 5 years (from nurseries and kindergartens)], and school children aged 5–11 years (primary schools) and 11–18 years (secondary and high schools)16. The ages 4.50–5.49 were considered 5 years old; similarly, 9.50-10.49 years of age were considered 10 years old. In the early stages 0 was at birth, 3 months was between 2.5 and 3.49 months, 6 months was between 5.5 and 6.49 months. In this way all ages were considered. We ensured that at least 200 children were recruited in each age-sex group, which gives sufficient precision for the construction of growth charts.

The Ministry of Education was sourced for information on the schoolchildren registered for the school year 2017/2018, 2018–2019, and 2019–2020 distributed by sex, geographical area, and educational level. The study took longer than planned due to the COVID-19 pandemic that disrupted all normal activities in the country. Taking into account the range of facilities available and the feasibility of conducting the study, such as trained staff, transportation, and funding, we decided to include 200–500 children in each age and sex group from schoolchildren registered for that school year. The children’s age, gender, head circumference, weight, and height were recorded as per standard procedures. This approach aimed to mitigate sampling bias and enhance the generalizability of findings to the broader UAE population. BMI was calculated using the standard formula: BMI = weight (kg) / (height (m))2. Participants’ head circumference, weight, and height measurements were obtained using calibrated instruments following standardized protocols to ensure accuracy and reliability. Participants’ BMI was categorized according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification criteria, which delineates BMI ranges into underweight (thin and severely thin), normal weight, overweight, and obesity categories. This classification system provides a standardized framework for interpreting BMI data and comparing results across different populations. The samples were taken from the cities of Abu Dhabi, Al Ain, Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman, Ras Al-Khaimah, Fujairah, and Umm al-Quwain, which cover the whole of the United Arab Emirates.

The measurement of length or height was made to the nearest 0.1 cm using an infant length board for infants and toddlers not able to stand without support and for all others a portable height gauge. Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a scale with non-detachable weights in infants without clothes or with pre-weighed diapers, and in older children in light clothing. Head circumference was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm with a non-stretchable disposable paper tape.

The PI (Y.M.A.) trained research assistants to perform the measurements. This team included 2 trained female paramedical assistants for each centre (a total of 10). Each assistant measured weight, height, and head circumference independently from the others. Height and head circumference were measured by two persons to minimize intra-observer error.

LMSchartmaker and SPSS 24 statistical packages were used to analyse the data. LMSchartmaker was used to create growth charts for BMI and head circumference, with the estimated 3rd, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th, and 97th age-sex specific percentiles. The growth chart distribution is characterized by the Box-Cox power λ (L), the median µ (M), and the coefficient of variation σ (S)16,17. Because of the lines’ jagged appearance, we used splines to smooth these values across ages. In the construction of the charts, using penalized likelihood the three curves [representing the median (M), coefficient of variation (S) and skewness (L)] were fitted as Cubic Splines by non-linear regression, which ensured that the curve was continuous in the first and second derivatives. The extent of smoothing required was expressed in terms of degrees of freedom. This made them particularly useful for smooth curve fitting. Since we had 23 data points we used 7 knots to ensure a smooth curve. The knots were placed at ages 0, 6 months, 12 months, 3 years, 7 years, 12 years, and 17 years. There were more points in the early ages as these regions were more clustered.

We decided on the degree of smoothing after visual inspection of the estimated percentile curves. The resultant percentile curves were exported to Microsoft Excel spreadsheets, and percentile graphs were made for ages 0–18 years. We removed impossible outliers before finalising the charts. Incomplete or unclear forms and ‘impossible’ outliers were excluded. An example of an ‘impossible outlier’ is when instead of registering a weight of 2.5Kg for a newborn baby the data recorder mistakenly registers a weight of 25 Kg or 0.25 Kg misplacing the dot. Therefore rather than correct the mistake we chose to exclude this measurement. (Table 1)

Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and proportions, were used to summarize BMI and HC distributions within the UAE population. Age- and gender-specific BMI and HC percentiles were determined using established statistical methods. BMI and HC growth charts were developed separately for boys and girls aged 0 to 18 years. The charts display BMI and HC percentiles ranging from the 3rd to the 97th percentile at regular intervals of age. The WHO criteria18 for underweight and overweight were used to calculate the percentage of children below the age of 18 years falling into each category According to WHO, the cut-off points are as follows: overweight: ≥1SD (equivalent to BMI 25 kg/m2 at 18 years), obesity: ≥2SD (equivalent to BMI 30 kg/m2 at 18 years), thinness: ≤2SD, severe thinness: ≤3SD. The Two-samples t-test was used to compare the means of BMI and HC of this study’s growth chart with the means of BMI and HC charts for each of the CDC19,20, WHO, and UAE growth charts (1992). These pairwise comparisons were made at different ages. However, the standard error of the means is reported instead of the standard deviation when we made these comparisons. The Fisher-Freeman-Halton Exact test was used to compare the prevalence of the BMI categories between the males and females for each age group. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Children had to be nationals of the UAE, and born to a father of Emirati nationality, healthy, born full-term, with no health issues that could affect their growth, to be included in the study.

Children who had anaemia other than iron-deficiency anaemia, diabetes mellitus, congenital malformations, and debilitating chronic diseases like asthma, were excluded. Children whose mothers had health conditions that could affect the growth of their children in the neonatal period (e.g. diabetes mellitus) were also excluded.

Results

Mean values

Tables 2 and 3 show the sample size, mean + SE values for head circumferences, and BMIs at each age and in both sexes. Anthropometric measurements were taken in 20,998 children from all seven Emirates. About 5% of the measurements, which were outliers, were discarded. Growth charts for BMI and Head Circumferences were constructed using the above methods and are shown in Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4. Growth charts were drawn for each sex and each age period. At birth, mean (± SD) BMI and head circumference were 13((± 0.09) Kg/m2, and 34.4 (± 0.9) cm respectively in boys, and, 12.8 ((± 0.11)Kg/m2and 34(± 1.1) cm respectively in girls. At 1 year of age, mean (± SD) BMI and head circumference was 17.4((± 0.08) Kg/m2 and 46.4(± 1.6) cm respectively in boys, and 17.1 ((± 0.07) Kg/m2 and 46.1(± 1.5) cm respectively in girls. There were no significant differences between the 2 sexes at these ages in any of the anthropometric measurements. At the age of 3 months, the HC of boys in the CDC data was larger than the ones in the present study. At the ages of 1–5 years, the differences were negligible. The BMI on the other hand shows significantly higher values in the present study than both the WHO data and the UAE 1992 data at all ages. Again, the CDC BMI data values are significantly higher than the present study data for all ages in both sexes.

Obese and overweight percentages

At one year of age the percentage of obese infants was 2.1% in girls and 2.8% in boys and overweight occurred in 12.3% of girls and 12.2% in boys. These values were not significantly different between the 2 sexes. At 5 years of age, 5.5% of girls were obese as against only 2.4% in boys, while the percentage of overweight was higher in boys (12.9%) than in girls (8.7%). The percentage of overweight and obese children combined was significantly greater in boys than in girls at the ages of 4 and 5 years, while the differences were not significant at the other ages. Only 1.7% of girls and 1.3% of boys were in the category of thinness. At 10 years of age, 4.9% of both boys and girls were obese and 13.5% of girls and 12.7% of boys were overweight. There were no underweight children in this age group. At adolescence (14 years of age) 4.8% and 4.2% of girls and boys respectively were obese and 13.9% and 12.9% of girls and boys respectively were overweight. There were no underweight boys or girls in this age group. Finally, at the age of 17 and 18 years combined, 5.3% of girls and 4.7% of boys were obese, and 10.75% and 14.55% of girls and boys respectively were overweight and this difference was not significant. There were also no underweight individuals in this age group (Table 3).

Comparisons

When comparing the present growth charts to the ones from CDC19,20, WHO (https://www.who.int/tools/growth-reference-data-for-5to19-years/indicators/bmi-for-age), and our own 1992 growth charts (12), we found that the CDC charts showed significantly higher values for BMI at all ages in both boys and girls. The present study has shown significantly higher values for BMI at all ages than the values of BMI in the UAE 1992 Growth charts in both boys and girls. The overweight and obesity rates in children at 1 year of age were 12.3% and 2.1% respectively in females, and 12.2% and 2.8% respectively in males. At the age of 3 years, the percentages of overweight and obesity were 9.8% and 1.7% respectively in females and 11.7% and 1.5% respectively in males. At the age of 10 years, the rates of overweight and obesity were 13.5% and 4.9% respectively in females and 12.7% and 4.9% respectively in males. And at the age of 18 years the rates of overweight and obesity were found to be 12.9% and 4% respectively in females and 16.5% and 4.9% respectively in males (Table 4). When we calculated the percentages of overweight and obesity in children of all ages taking into consideration 1992 cut-off points at every age in both sexes we found that the rates of obesity were significantly higher in the present cohort. The rates of overweight were not significantly different in most of the ages in both sexes (Tables 5 and 6). To show whether we could use the 1992 data as a basis to detect obesity and as an example, at the age of 3, in both sexes, the obesity and overweight rates combined were more than 65% of all children of that age.

Discussion

A WHO technical report in 199518 divided the BMI measurements into 4 categories: underweight, normal, overweight, and obese. An adult person is underweight if his/her BMI is in the range of 15 to 19.9, normal weight if the BMI is 20 to 24.9, overweight if the BMI is 25 to 29.9, and obese if it is 30 to 35 or greater. The BMI has now been established as the most common and most studied measurement and has been most commonly used in children because measurements can be made easily on infants and children. However, BMI has limited value when measuring body composition. Both lean mass and fat mass correlate very well with BMI. Despite this, BMI can only be used to follow short-term changes in body composition as changes in the BMI standard deviation score21 in the short term can be attributed primarily to changes in fatness. It does not have the required accuracy as an absolute measure of fatness in individuals21,22, although some studies do seem to suggest this23,24,25. Although there are shortcomings, most work on childhood obesity is based on BMI. The major limitation of the BMI is the inability to differentiate between muscle and fat. There has been little data on growth and obesity in United Arab Emirates (UAE) children except for the UAE skinfold or BMI standard reference charts (12). A large-scale epidemiological study (n = 44,942) conducted in Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates (UAE), confirmed obesity was steadily increasing in those aged 3–18 years; each year an additional 2.36% were classified as obese and 0.28% as extremely obese26. The United Arab Emirates Multicentre Growth Study 2 (UAEMGS 2) was undertaken to determine a range of anthropometric measurements and to construct growth charts for each of these measurements.

Consistent with global trends and previous studies27,28, our BMI charts demonstrate rapid increases in BMI during infancy and early childhood, followed by a stabilization period during adolescence. Sex-specific differences are evident in older age groups, with boys generally exhibiting higher BMIs compared to girls at ages 17 and 18, but girls showing higher BMIs at ages 10–15 years, particularly during adolescence, echoing findings from studies in other populations29,30. These differences likely reflect variations in body composition and growth rates between the sexes.

There were a few studies done on BMI in the UAE one of which was on a sample of schoolchildren 5–17 years of age during the years 1998–1999. In that study prevalence of overweight and obesity was found to be 21.5% and 13.7% respectively31. Another study showed that in the 14–17 years age group, the prevalence of overweight and obesity was 19% and 13.3%, respectively, in boys and 16.9% and 17.6%, respectively, in girls2. However this study was not restricted to UAE nationals only but included the expatriate population as well, while the present study is limited to the UAE nationals only. In our previous study, we found the prevalence of obesity and overweight in the adolescent age group to be lower at 9.94% and 15.16%, respectively, in females and 6.08% and 14.16%, respectively, in males12. In the present study, the corresponding figures were 4.9% obese, and 13.7% overweight females, and 4.17% and 9.5% obese and overweight males respectively in the adolescent age group. In contrast to what we expected the rates of obesity and overweight had decreased in both adolescent boys and girls from the last study to this one. When using cut-off points from the 1992 data and calculating the rates of obesity and overweight we found impossible percentages with 65% overweight and obese children at the age of 3 years in both sexes, and similar figures in all ages in both sexes. In a recent publication13 using data from the present cohort, we showed greater height and weight than those of the 1992 cohort at all ages in both sexes. Therefore, it is obvious from this analysis that there is a need for a new growth chart. Two more studies done before 2010 found the obesity rate to be 8% in both males and females and the overweight rate to be 16.5% and 16.9% in males and females, respectively in one study3 and 14% overweight and 9% obesity in the other study32. Our overweight and obese rates for this age group were lower than in both these studies. In the present study the rates of overweight and obesity gradually increased with age in both sexes, following a similar trajectory but reaching slightly higher rates in the females. These changes were as expected. The impact of population nutrition on BMI would be difficult to estimate, and to provide an algorithm converting new values from old would be impossible. These children did not suffer from malnutrition and poor health therefore there were no constraints to growth. Therefore, these references show normal growth under optimal conditions and can be used in the whole country and by neighbouring countries that have similar diets and habits. We did not have mothers who smoked which would have added another negative factor to achieve optimal growth.

The CDC and WHO growth charts are widely used in many countries to assess the nutritional status and growth of children. These charts are based on large international samples, including different ethnicities, and reflect global trends. It is important to note that the CDC charts tend to reflect growth patterns that the dietary habits, lifestyle, and genetics of populations in the United States may influence. While the CDC and WHO charts are internationally recognized, they may not fully capture the specific characteristics or trends of certain regions, such as the UAE. However, the Comparison with UAE 1992 Growth Charts is particularly relevant because it involves a localized context, potentially reflecting regional dietary patterns, socioeconomic status, healthcare access, and physical activity levels that are specific to the UAE. Higher BMI values in the present study compared to the 1992 UAE growth charts could be due to changes in diet and lifestyle, and increases in height13 over time. Since 1992, there have been significant changes in the UAE, including increased urbanization, globalization of food patterns (such as the introduction of fast food), and changes in physical activity levels (with more sedentary behavior, especially among children). These changes could lead to higher BMIs today than in the past. Another reason could be health interventions or awareness: The current population may be more aware of health and fitness, leading to an increased focus on weight and height, which may affect the data. Another reason could be a potential improvement in healthcare and nutrition. Increased access to healthcare and improved nutrition over time could also contribute to changes in growth patterns, although this might not be enough to explain the magnitude of BMI changes observed.

The skull undergoes the greatest changes in the first 2 years of life33, with the intracranial volume doubling during the first 6–9 months of life9. Subsequently, in the next 6 months it increases by another 20%9. Post-mortem studies and CT scans have shown a significant positive correlation between brain volume and head circumference in deceased neonates34,35. Similarly, this finding is in line with MRI studies of older children8. These studies have established the head circumference measure (HC) as a screening parameter for intracranial volume36,37,38. Analysis of head circumference charts reveals a steady increase in head size during infancy, consistent with findings from previous studies39,40. However, deviations from expected head circumference measurements may indicate underlying neurological abnormalities or developmental delays, aligning with the findings of studies linking head circumference to brain development41,42,43. At birth, the head circumference measurements were taken up to 24 h after birth which may have resulted in lower HC values due to the resolving of scalp edema, hence the apparent lower values. Our charts provide reference values specific to the UAE population, enabling early detection and intervention in cases of abnormal head growth.

HC measurement in early childhood/infancy reflects brain volume and growth due to the open cranial sutures and fontanelles. It can be a valuable tool to analyse brain growth and development in this age group44,45. Studies evaluating the utility of HC measurements in childhood have produced mixed results. Many studies suggest HC monitoring when the measurements are above + 2 SDs44,46,47. In children at risk, including those exposed to alcohol during prenatal period48, born as a preterm49,50 and having very low birth weight51, HC was shown to be related to cognition/development. Similar findings have been reported from typically developing children with evidences from a large multinational LMIC community based birth-cohort study52, and from cohort studies in India53, UK54, and Uruguay55. An Indian birth-cohort study showed HC at birth was related to learning, memory and storage and visuospatial abilities around 10 years of age53. There have been many publications showing an association of head circumference and intelligence, one of them being a recent systematic review56. It is also associated with better school performance, and smaller HC at 2 years of age is negatively associated with cognition at both 2 and 5 years of age. A positive correlation was found between head circumference and Bayley scores at 18 months, and also a positive correlation between head circumference at discharge and at 5 months with the three domains of the Bayley57. The Head Circumference charts do exist for children up to 18 years of age [eg. Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Glasgow58. Therefore, although for normally growing children there is no necessity to monitor HC growth, for others like children with craniosynostosis and other conditions with abnormally small or large heads there is, and therefore there is a need for reference HC values for every age.

The BMI and head circumference charts developed in this study serve as valuable tools for healthcare providers in monitoring the growth and development of UAE children. By comparing individual measurements to population norms, clinicians can identify children at risk of health problems or developmental delays and intervene early to optimize outcomes. These charts also facilitate discussions with parents and caregivers about healthy lifestyle habits and preventive measures, aligning with the goals of previous interventions aimed at reducing childhood obesity and promoting early childhood development59,60.

Moving forward, efforts should focus on disseminating these charts widely among healthcare professionals in the UAE and integrating them into clinical practice guidelines. Continuous data collection and analysis are essential to ensure the relevance and accuracy of growth references in an evolving population. Future research could also explore the impact of socioeconomic and environmental factors on growth trajectories in the UAE context, informing targeted interventions to address health disparities and promote equitable health outcomes for all children.

Potential limitations of the study are reliance on sampling biases, and inherent measurement errors in BMI calculation. In a multi-centre study or a study involving multiple researchers, differences in how weight and height are measured could introduce inconsistencies in the data. In the present study, standardized protocols were followed to ensure that all participants were measured in the same way to minimize such errors. Sampling bias can affect the generalizability of the study’s results. If the sample does not accurately reflect the broader population, the study’s findings may not apply to children and adolescents in the UAE more generally, especially those from underrepresented or disadvantaged groups. We have minimised this potential limitation by the rigorous multi-stage random sampling technique we used. Measurement errors can lead to inaccurate BMI values, which might result in incorrect conclusions about the nutritional status or growth trends in the study population. If BMI values are inaccurately measured, this could distort the comparison with other growth charts, making the BMI values in the present study appear higher or lower than they actually are. Again we used two separate trained individuals to measure the same child to minimise this limitation.

Data availability

Original data and materials are available with the authors YMA and MZ.

References

Abdulrazzaq, Y. M., Moussa, M. & Nagelkerke, N. National growth charts for the United Arab Emirates. J. Epidemiol. 18 (6), 295–303 (2008).

Al Haddad, F., Al-Nuami, Y., Little, B. B. & Thabit, M. Prevalence of obesity among schoolchildren in the United Arab Emirates. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 12 (4), 498–502 (2000).

Al-Hourani, H. M., Henry, C. J. & Lightowler, H. J. Prevalence of overweight among adolescent females in the United Arab Emirates. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 15 (6), 758–764 (2003).

Barbeau, P. et al. Correlates of individual differences in body-composition changes resulting from physical training in obese children. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 69, 705–711 (1999).

UAE Statistical annual report. Statistics and research centre, ministry of health and community. Publication of ministry of health and prevention, UAE. (2020).

Gale, C. R., Walton, S. & Martyn, C. N. Foetal and postnatal head growth and risk of cognitive decline in old age. Brain 126, 2273–2278 (2003).

Vernon, P. A., Wickett, J. C., Bazana, P. G. & Stelmack, R. M. The neuropsychology and psychophysiology of human intelligenc. In: (ed Sternberg, R. J.) Handbook of Intelligence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 245–264. (2000).

Bartholomeusz, H. H., Courchesne, E. & Karns, C. M. Relationship between head circumference and brain volume in healthy normal toddlers, children, and adults. Neuropediatrics 33, 239–241 (2002).

Kamdar, M. R., Gomez, R. A. & Ascherman, J. A. Intracranial volumes in a large series of healthy children. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 124, 2072–2075 (2009).

MacLullich, A. M. et al. Intracranial capacity and brain volumes are associated with cognition in healthy elderly men. Neurology 59, 169–174 (2002).

Falk, D. et al. LB1’s virtual endocast, microcephaly, and hominin brain evolution. J. Hum. Evol. 57, 597–607 (2009).

Abdulrazzaq, Y., Nagelkerke, N. & Moussa, M. A. UAE population reference standard charts for body mass index and skinfold thickness, at ages 0–18 years. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 62 (7), 692–702 (2011).

Abdulrazzaq, Y. M., Aburawi, E., Abdulrahman, M., Alshamsi, A. & Zidan, M. Reference growth charts for height and weight, for the UAE, the UAEMCGS 2 study. Annals Hum. Biology 2024 DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/03014460.2024.2437167

Hayase, T., Muramatsu, T., Fujita, O., Okada, A. & Muramatsu, S. The influence of the war experience upon the physical development among children and young adults. Iris Health. 3, 17–21 (2003). (In Japanese).

Kawahata, A. The acceleration of growth and development of Japanese school students. Part XXII before and after World War II. Gakkou Hoken Kenkyu. 21, 497–500 (1979). (In Japanese).

National Health Statistics. Reports Number 63 February 11, (2013).

Cole, T. J. Conditional reference charts to assess weight gain in British infants. Arch Dis Child 1995;73:8–16. (1995).

WHO. Physical Status: The Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry: Report of a World Health Organization (WHO) ExpertCommittee (World Health Organization, 1995).

Fryar et al. Mean Body Weight, Height, Waist circumference and body Mass Index among children and adolescents: United States, 1999–2018. National Health Statistics Report 2021; number 160: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/index.htm

2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: Methods and development. Vital and Health Statistics. series 11, Number 246.May (2002).

Keys, A., Fidanza, F., Karvonen, M. J., Kimura, N. & Taylor, H. L. Indices of relative weight and obesity. J. Chron. Dis. 25 (6), 329Y343 (1972).

Davies, P. S. W. Body composition assessment. Arch. Dis. Child. 69, 337–338 (1993).

Ellis, K. J., Abrams, S. A. & Wong, W. W. Monitoring childhood obesity: Assessment of the weight/height2 index. Am J Epidemiol 1999;150:939 – 946. (1999).

Chan, Y. L., Leung, S. S., Lam, W. W., Peng, X. H. & Metreweli, C. Body fat estimation in children by magnetic resonance imaging, bioelectrical impedance, skinfold and body mass index: a pilot study. J. Paediatr. Child. Health. 34, 22–28 (1998).

Pietrobelli, A. et al. Body mass index as a measure of adiposity among children and adolescents: a validation. J. Pediatr. 132, 204–210 (1998).

Baniissa, W. et al. Prevalence and determinants of overweight/obesity among school-aged adolescents in the United Arab Emirates: a cross-sectional study of private and public schools. BMJ Open. 10, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038667 (2020). e038667.

Jones, M. M. et al. Parents’ perceptions and use of school-based body mass index report cards. J. Sch. Health. 88 (11), 787–793. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12685 (2018).

Cole, T. J., Bellizzi, M. C., Flegal, K. M. & Dietz, W. H. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: International survey.

Javed, A. A. et al. Body mass index and all-cause mortality in older adults: a scoping review of observational studies. Obes. Rev. 21 (8), e13035 (2020).

Ogden, C. L. et al. Differences in obesity prevalence by demographics and urbanization in US children and adolescents, 2013–2016.

Malik, M. & Bakir, A. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among children in the United Arab Emirates. Obes. Rev. 8, 15–20 (2007).

Sheikh-Ismail, L. I. et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among adult females in the United Arab Emirates. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 60 (Suppl 3), 26–33 (2009).

Slovis, T. Anatomy of the Skull 11th edn (Mosby Elsevier, 2007).

Cooke, R., Lucas, A., Yudkin, P. & Pryse-Davies, J. Head circumference as an index of brain weight in the fetus and newborn. Early Hum. Dev. 1, 145–149 (1977).

Lindley, A., Benson, J., Grimes, C., Cole, T. & Herman, A. The relationship in neonates between clinically measured head circumference and brain volume estimated from head CT-scans. Early Hum. Dev. 56, 17–29 (1999).

Bruner, E. Geometric morphometrics and paleoneurology: Brain shape evolution in the genus homo. J. Hum. Evol. 47, 279–303 (2004).

Holloway, R. L. The evolution of the primate brain: Some aspects of quantitative relations. Brain Res. 7, 121–172 (1968).

Howells, W. W. Howells’ craniometric data on the internet. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 101, 441–442 (1996).

Wang, L. et al. Body-mass index and obesity in urban and rural China: findings from consecutive nationally representative surveys during 2004–18. Lancet 398, P53–63 (2021).

Elmali, F. et al. Head circumference growth reference charts for Turkish children aged 0–84 months. Pediatr. Neurol. 46 (5), 307–311 (2012).

Gale, C. R., O’Callaghan, F. J., Bredow, M., Martyn, C. N. & Avon longitudinal. Study of parents and children study team. The influence of head growth in fetal life, infancy, and childhood on intelligence at the ages of 4 and 8 years Pediatrics; 118(4):1486-92. (2006). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-2629

Bartholomeusz, H. H., Courchesne, E. & Karns, C. M. Relationship between head circumference and brain volume in healthy normal toddlers, children, and adults. Neuropediatrics 33 (5), 239–241. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2002-36735 (2002).

Bach, C. C., Henriksen, T. B., Larsen, R. T., Aagaard, K. & Matthiesen, N. B. Head circumference at birth and school performance: a nationwide cohort study of 536,921 children. Pediatr. Res. 87 (6), 1112–1118. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-019-0683-2 (2020). Epub 2019 Nov 28. PMID: 31779026.

Wright, C. M. & Emond, A. Head growth and neurocognitive outcomes. Pediatrics 135 (6), e1393–e1398. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-3172 (2015).

Ivanovic, D. M. et al. Head size and intelligence, learning, nutritional status and brain development. Head, IQ, learning, nutrition and brain. Neuropsychologia 42 (8), 1118–1131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2003.11.022 (2004).

Sniderman, A. Abnormal head growth. Pediatr. Rev. 31 (9), 382–384. https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.31-9-382 (2010).

Zahl, S. M. & Wester, K. Routine measurement of head circumference as a tool for detecting intracranial expansion in infants: what is the gain? A nationwide survey. Pediatrics 121 (3), e416–e420. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-1598 (2008).

Treit, S. et al. Relationships between head circumference, brain volume and cognition in children with prenatal alcohol exposure. PLoS One ;11(2) (2016).

Raghuram, K. et al. Head growth trajectory and neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm neonates. Pediatrics ;140(1); (2017).

Cheong, J. L. Y. et al. Head growth in preterm infants: correlation with magnetic resonance imaging and neurodevelopmental outcome. Pediatrics 121 (6), e1534–e1540 (2008).

Scharf, R. J., Stroustrup, A., Conaway, M. R. & DeBoer, M. D. Growth and development in children born very low birthweight. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 101 (5), F433–F438 (2016).

Scharf, R. J. et al. Early childhood growth and cognitive outcomes: Findings from the MAL-ED study. Matern Child. Nutr. ;14(3). (2018).

Veena, S. R. et al. Association of birthweight and head circumference at birth to cognitive performance in 9- to 10-year-old children in South India: Prospective birth cohort study. Pediatr. Res. 67 (4), 424–429 (2010).

Gale, C. R., O’Callaghan, F. J., Bredow, M. & Martyn, C. N. The influence of head growth in fetal life, infancy, and childhood on intelligence at the ages of 4 and 8 years. Pediatrics 118 (4), 1486–1492 (2006).

Bove, I., Miranda, T., Campoy, C., Uauy, R. & Napol, M. Stunting, overweight and child development impairment go hand in hand as key problems of early infancy: Uruguayan case. Early Hum. Dev. 88 (9), 747–751 (2012).

Freire, M. B. O. et al. Head Circumference and intelligence, schooling, employment, and income: A systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 24, 709 (2024).

De Sequeira Mayrink, M. L. et al. The trajectory of head circumference and neurodevelopment in very preterm newborns during the first two years of life: A cohort study. J. Pediatr. (Rio J). 100 (5), 483–490 (2024).

Nelhaus, G. Head circumference from birth to 18 years. Practical composite international and interracial graphs. Pediatrics 41 (1), 106–114 (1968).

Bleich, S. N. et al. Interventions to prevent global childhood overweight and obesity: A systematic review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 6 (4), 332–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30358-3 (2018). Epub 2017.

Gato-Moreno, M. et al. Early nutritional education in the prevention of childhood obesity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18 (12), 6569. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126569 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to the Al Jalila Foundation for providing the funds for this study under Grant no. AJF201712. We are grateful to the research assistants and nurses in different health centres, hospitals, kindergartens, and schools in all 7 Emirates for performing the anthropometric measurements and for obtaining all data. Finally, it is my pleasure to value the support provided by the Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health, Department of Health Abu Dhabi, and Dubai Health Authority at every step of the project up to its completion.

Funding

The funding was provided by the Al Jalila Foundation, Dubai, UAE, for this study under Grant no. AJF201712.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YMA contributed to the conception and design of the work, obtaining research funds, analysis of data, training of research assistants, interpretation of data, and drafting and editing the manuscript. EMA contributed to the conception of the work, acquisition of data, and editing of the manuscript. MAA contributed to the conception and acquisition of data. AAS contributed to the acquisition of data and overall responsibility over one centre. MZ contributed to the conception of the work, analysis of data, interpretation of data, and revision of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was received from relevant Institutional Review Boards or Ethics Committees to ensure compliance with ethical guidelines governing human subjects research in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ministry of Health Ethics Committee, DHA Ethics Committee Dubai, Tawam Hospital Institutional Review Board, Al Ain, Kanad Hospital Ethics Committee, Al Ain, and Corniche Hospital Ethics Committee, Abu Dhabi gave their approval for the study.

Consent for publication

All authors consented to the publication.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from participants or their legal guardians before data collection and measures were implemented to safeguard their privacy and confidentiality throughout the study duration.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdulrazzaq, Y.M., Aburawi, E.H., Abdulrahman, M.A. et al. Body mass index and head circumference growth charts for the United Arab Emirates-the UAEMCGS 2 study. Sci Rep 15, 6477 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90942-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90942-z