Abstract

A novel lytic bacteriophage, PSA-KC1, was isolated from wastewater. In this study, the whole genome of the bacteriophage PSA-KC1 was analyzed, and its lytic properties were assessed. PSA-KC1 has a linear double-stranded DNA genome with a total length of 43,237 base pairs and a GC content of 53.6%. In total, 65 genes were predicted, 46 of which were assigned functions as structural proteins involved in genome replication, packaging or phage lysis. PSA-KC1 belongs to the genus Septimatrevirus under the Caudoviricetes class. The aim of this study was to investigate the efficacy of the lytic bacteriophage PSA-KC1 and compare it with that of the Pyophage phage cocktail on 25 multi drug resistant (MDR) Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from sputum samples of cystic fibrosis patients. Seventeen of these strains were susceptible (68%) to the PSA-KC1 lytic phage we isolated, whereas eight clinical strains were resistant. However, 22 (88%) of the P. aeruginosa strains were susceptible to the Pyophage cocktail, and three (12%) were resistant to the Phage cocktail. At the end of our study, a new lytic phage active against multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa strains from CF patients was isolated, and its genome was characterized. Since the PSA-KC1 phage does not contain virulence factors, toxins or integrase genes, it can be expected to be a therapeutic candidate with the potential to be used safely in phage therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bacteriophages are bacterial viruses that can specifically infect bacteria. Bacteriophages were first discovered in 1915 by Frederick Twort, and their therapeutic application was made by D’Hérelle in 1917. Phages, the most abundant biological entity in the world, have nucleic acids consisting of DNA or RNA. Bacteriophage (phage) therapy is a treatment in which bacteria are killed by lytic phages. Phage therapy has been used successfully in Russia and Georgia since its discovery and later in Poland. Today, phage therapy centers are active in these countries as well as in many European countries. Phage therapy is applied in humans to treat surgical wound infections, typhoid fever, dysentery, peritonitis, urinary tract infections, otitis externa, and pulmonary infections1,2,3as well as cystic fibrosis (CF)4,5,6,7,8.

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is caused by a mutational change in the gene encoding the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein located on chromosome 79. The lungs, intestines, sweat glands, pancreas, and biliary and liver systems are usually affected. The secretion of thickened mucus in affected organs causes mucus obstruction. CF is especially common in white populations, with a frequency of between 1/2500 and 1/20,000 in newborns10. Mucociliary clearance begins to deteriorate with the failure of chlorine and fluid secretions in the respiratory tract epithelium. Additionally, obstructions occur in the ducts in the liver and pancreas because of disturbances in ion transport. Cystic fibrosis severely affects the lungs of patients, decreasing their lung capacity and predisposing them to infections that result in increased mortality rates. There are approximately 70,000 CF patients worldwide, with approximately 1000 new cases added annually11. CF causes various complications, such as bronchiectasis, pneumonia, pneumothorax, respiratory failure, diabetes, gallstones, intestinal obstruction, intussusception, and electrolyte imbalance12. The most common infectious pathogens observed in CF patients are Staphylococcus aureus and P. aeruginosa13. P. aeruginosa is one of the most common bacterial pathogens isolated from CF patients, whereas P. aeruginosa infection is detected in 48% of patients with CF. Furthermore, P. aeruginosa is one of the main causes of multidrug-resistant nosocomial infections, with the ability to lead to biofilm formation, and thus, P. aeruginosatends to stay on various surfaces for a prolonged period of time14. Persistent and chronic bacterial infections leading to respiratory malfunction are the most frequent causes of death in patients with CF. P. aeruginosais believed to be the most significant bacterial infection in CF, as it is associated with lung disease and ultimately death15.

Antibiotic combinations are used more than once a day to provide the necessary treatment dose for P. aeruginosalung infections. Aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, carbapenems, cephalosporins and colistin are generally used for treatment. The intensive use of these drugs is both expensive and causes antibiotic resistance, drug interactions, side effects, and especially nephrotoxicity. As a result of the failure of treatment with existing antibiotics, new treatment options, such as gene therapy and phage therapy, have been developed16,17.

Several studies have documented the therapeutic potential of phage therapy in the treatment of infectious diseases caused by multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosastrains18,19,20. Additionally, phage therapy has been reported in lung transplantation individuals diagnosed with CF, and the effectiveness of phage therapy in treating lung infection has been reported in various animal model studies4,5,6,7,8.

The Pyophage cocktail was successfully applied to P. aeruginosastrains from CF patients21. The Pyophage cocktail is a commercial mixture containing phages effective against streptococci, staphylococci, Shigella, Salmonella, E. coli and P. aeruginosa. Pyophage cocktail contained four Pseudomonas phages according to metagenomic sequencing; Pseudomonas phage PEV2, Pseudomonas phage TL (NC_023583.1), Pseudomonas phage phiKZ, Pseudomonas phage CHA P1, and Pseudomonas phage vB PaeP22.

In this study, a novel lytic phage active against multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa strains from CF patients was isolated from wastewater, and its genome was characterized. The aim of this study was to investigate the efficacy of the lytic bacteriophage PSA-KC1 and compare it with that of the Pyophage phage cocktail on 25 MDR P. aeruginosa strains isolated from sputum samples of cystic fibrosis patients.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains

In total, 25 clinical strains of multidrug resistant (MDR) P. aeruginosa were isolated from sputum samples collected from cystic fibrosis patients in the Medical Microbiology Laboratory at Cerrahpaşa Faculty of Medicine from September 2019 to September 2020 and were used in the study. The study was approved by İstanbul University-Cerrahpasa, Cerrahpasa Medical Faculty, Clinical Research Ethics Committee (83045809-604.01.02). All methods were conducted in compliance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

The sputum samples were streaked on 5% sheep blood agar, MacConkey agar and chocolate agar plates, and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The grown colonies were identified using MALDI-TOF MS (Bruker, Germany). Antimicrobial susceptibility test were performed on all P. aeruginosa strains isolated from the sputum samples. The disk diffusion method was applied according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) guidelines, and the results were assessed using the EUCAST criteria.

Isolation and purification of bacteriophage PSA-KC1

MDR P. aeruginosa was used as a host for phage isolation. MDR P. aeruginosa was grown on Tryptic Soy Agar (Merck) plates at 37 °C for 24 h. A single colony was then added to 5 ml of broth medium. Inoculation was performed, and the bacteria were then incubated at 37 °C for 2–4 h in a rotating incubator until they reached the logarithmic phase. Bacterial concentrations were measured after incubation and adjusted to 1 × 107−108X cells/ml according to McFarland standards. The double overlay method was used for the isolation of bacteriophages.

Double overlay method

Two wastewater samples from the activated sludge process were collected from the Pasakoy Advanced Biological Treatment Plant (Istanbul, Turkey) and East Wastewater Treatment Plant (Bursa, Turkey) in August and November 2020. The samples were subsequently centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min to eliminate coarse particles (Nuve NF1200 with an RS 100 rotor, Turkey). The resulting supernatant was filtered by vacuum filtration via 0.22 membrane filters (Interlab, Turkey) to remove bacteria and then stored at 4 °C. Ten milliliters of sterile broth and 10 mL of wastewater were mixed with 0.1 mL of logarithmic culture of the isolated MDR P. aeruginosa strains. This mixture was incubated in a shaking incubator at 37 °C and 50 rpm for 24 h. After incubation, the culture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected, and 0.5 mL of chloroform was added to kill the remaining bacteria. All isolated 25 MDR P. aeruginosa strains were used for bacteriophage isolation.

Three milliliters of liquefied semisolid agar (maintained at 50 °C) (0.5% TSA agar, Merck), 100 µL of bacterial culture, and 300 µL of different dilutions of the phage-enriched lysates were combined in 15 mL Falcon tubes. The mixtures were immediately poured onto TSA plates, and after the soft agar solidified, the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Plaque formation after incubation confirmed the presence of lytic bacteriophages23. Single plaques were selected and resuspended in SM buffer (200 mM NaCl2, 10 mM MgSO4, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 2% gelatine). This procedure was repeated at least three times to purify the phages. The double overlay method was used to proliferate the purified bacteriophages. Soft top agar was collected from the plates and centrifuged (10,000 rpm, 25 min). The obtained supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter. The purified phages were stored at − 80 °C. The final concentration of the phages was 3 × 108PFU/mL24.

Determination of the One-Step growth curve

One-Step Growth Curve analysis performed according to Kropinski25 protocol. A total of 0.1 mL of phage suspension (107 pfu/mL) was added to 9.9 mL of P. aeruginosa strains (4.0 × 108) in TSB and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. The bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation (~ 5 min at the full speed of the centrifuge), after which the supernatant was discarded. The bacterial pellet was resuspended in 10 mL of fresh medium. Phage titers were measured by collecting samples at 5-minute intervals for up to 60 min. The double overlay method was used to determine the phage titers. The burst size was evaluated26. The experiment was performed in triplicate to reduce variability.

Propagation of the pyophage cocktail

The pyophage cocktail was obtained from the Eliava Institute in Tbilisi, Georgia. Single colonies of P. aeruginosa were inoculated on TSA media and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After incubation, single colonies were inoculated into 10 ml of medium and incubated in a shaker at 37 °C for 24 h. The bacterial concentrations were then adjusted to 106 −107 cfu/ml. In vitro phage susceptibility was determined via the spot test method.

Phages were diluted in serial 10-fold dilutions, and the double agar layer method was employed. For phage propagation, 3 ml of 0.5% semisolid agar and 100 µl of bacterial cells were added to a 15 ml Falcon tube. Three hundred microliters of the diluted phage mixture were then added to this mixture. The mixture was spread on solid media and allowed to solidify. After 18–24 h of incubation, the phage plaques on 0.5% agar were scraped from the Petri dish and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 25 min. The supernatant was passed through a 0.22 μm filter, and this process was repeated to obtain a concentrated stock of phage.

Evaluation of the phage host range via the spot test method and the EOP

The host range of the bacteriophage PSA-KC1 and pyophage cocktail was investigated via the spot test method. A thick line was drawn on the TSA via a loopful of bacteria. Five microliter drops of phage suspension were pipetted onto the bacterial line and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The absence of growth under the drops after incubation indicated that the phage had infected the host bacteria.

The efficiency of plating (EOP) method was used to test the ability of phages to infect different bacterial strains. Briefly, serially diluted phage lysate was dropped in 5 ml drops onto a double-layer agar plate inoculated with bacteria and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Phage and lysis residues were evaluated to calculate the EOPs. The number of EOPs produced in triplicate was calculated according to the formula of the average PFU of the target strain divided by the average PFU of the original bacteria. An EOP greater than 0.5 indicated high infection efficiency, whereas EOP values between 0.001 and 0.1 indicated low infection efficiency. Phages were considered inefficient if the EOP value was less than 0.00127,28.

Evaluation of phage stability under different thermal and pH conditions

The viability of phage PSA-KC1 at different pH values and temperatures was investigated. To determine pH stability, a known concentration of PSA-KC1 was incubated for 1 h in TSB adjusted to various pH values (3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0, 9.0, 10.0 and 11.0). Three parallel experiments were conducted for each pH. Similarly, to evaluate the temperature stability of phage PSA-KC1, a known concentration of PSA-KC1 was incubated at different temperatures (28, 37, 40, 45, 50, 55, 65 and 75 °C) for 1 h in TSB. The experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Bacteriophage PSA-KC1 genome sequencing and analysis

Isolation of bacteriophage genomic DNA

PEG6000 precipitation was used to concentrate the bacteriophage PSA-KC1. The bacteriophage PSA-KC1 and PEG 6000 (10% w/v) solutions were mixed by shaking for 1 min and incubated at + 4 °C with rotation at 100 rpm overnight. After incubation, the mixture was centrifuged (at 12,000×g) for 4 h, and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was suspended in 200 µl of water. Total viral genomic DNA was obtained via the Roche MagNA pure LC total nucleic acid isolation kit in the Roche MagNA pure LC system (Penzberg, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and quantity of viral genomic DNA were measured by using a Thermo NanoDrop 2000c (Penzberg, Germany).

Sequencing of phage genomic DNA: minion™ sequencing and data analysis

The whole-genome sequencing of phage PSA-KC1 was conducted using the ONT-Ligation Sequencing Kit (ONT, Cat. No. SQK-LSK109) and ONT-Native Barcoding Kit (ONT, Cat. No. EXP-NBD104-114). The genomic DNA library, along with adapters, sequencing buffers and loading beads, was combined and loaded onto the ONT MinION Flowcell (v. 9.4.1, Cat. No. FLO-MIN106D). Raw fast5 files were generated via the MinKNOW (v. 22.03.5) GUI program. Subsequently, the barcode and adapter sequences were removed, and quality filtering was conducted via the ONT-guppy (v. 6.0.6) CLI program. The quality of the reads was assessed, and average quality scores were determined via FastQC v0.11.9 (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) and QSCORE (https://www.drive5.com/qscore/). Contig sequences were obtained though the flye de novo assembler (v. 2.8) pipeline. These contigs were then aligned against the NCBI nt reference database to identify the closest relatives. The overall identity percentage was calculated via the following formula: overall identity % = coverage × identity %. Gene prediction was carried out via Prokka29. The predicted genes were annotated via BLASTp via the NCBI nr database. The absence of antibiotic resistance genes in the PSA-KC1 genome was confirmed using the deepARG program30. Potential tRNA genes were identified using the tRNAscan-SE program31, whereas the presence of genome termini was assessed using ccfind32. Rho-independent terminators were predicted using ARNold33,34,35. The data supporting this article are available in the GenBank Nucleotide Database at [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/] and can be accessed with the OQ412632 accession number.

Results

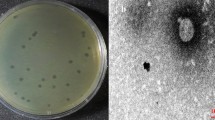

The phage PSA-KC1 was isolated from an environmental wastewater sample. After overnight cultivation at 37 °C, we detected small transparent, clear, regular plaques on a lawn of P. aeruginosa (Fig. 1), indicating that they were virulent phages. Spot tests revealed that the phage PSA-KC1 could infect most P. aeruginosa clinical isolates. Analysis of the genomic sequence revealed that phage PSA-KC1 belongs to the Septimatrevirus genus within the Caudoviricetes Class.

Physiological characterization of the bacteriophage PSA-KC1

The latent time and lytic cycle of the bacteriophage PSA-KC1 were approximately 35 min, with a burst size of approximately 85 PFU/mL (Fig. 2A). Thermal stability tests confirmed that the bacteriophage PSA-KC1 was largely stable at temperatures between 28 and 75 °C (Fig. 2B). The optimal efficacy of phage PSA-KC1 was observed at temperatures of 37–45 °C; as the temperature increased, the phage activity began to decrease. The phage showed the greatest effectiveness at a pH of 7. The titers of phage PSA-KC1 were consistent across various pH environments (4–10). However, as the pH increased, the infectivity of phage PSA-KC1 began to decrease, with titers sharply decreasing at pH 3 and pH 11 (Fig. 2C).

Efficiency of plating (EOP)

The 17 Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates that tested positive in the spot test were assayed for EOP. Eight of the total isolates showed a highly productive infection with an EOP value ≥ 0.5. Six isolates were found to have medium productivity (EOP between 0.1 and 0.5) and three isolates were found to have low productivity (EOP values between 0.001 and 0.1) (S Table 3).

Genome annotation of phage PSA-KC1

Genome analysis and phylogeny of phage PSA-KC1

The Oxford Nanopore MinION sequencing approach was utilized to sequence the phage genome. A total of 2,436,436 base pairs were detected in 774 reads, resulting in a genome coverage of 48.72X. The phage PSA-KC1 has a linear double-stranded DNA genome with a total length of 43,237 base pairs and a GC content of 53,6%. The genomic map and genetic characteristics of phage PSA-KC1 are depicted in Fig. 3. Whole-genome sequence alignment of Bacteriophage PSA-KC1 against other bacteriophages in the NCBI refseq data revealed that the bacteriophage PSA-KC1 shared the highest similarity (identity: 96.4%, coverage: 94%) with Pseudomonas phage 73 (GenBank: NC_007806.1), followed by Pseudomonas phage vB_PaeS_SCH_Ab26 (GenBank: NC_024381.1) (Fig. 4), Pseudomonas phage vB_Pae-Kakheti25 (GenBank: NC_017864.1), and Stenotrophomonas phage vB_SmaS-DLP_2 (GenBank: NC_029019.1), with 96%, 93%, and 90% coverage and 95.75%, 96.5%, and 96.01% identity, respectively (Table 1). The highest overall identity percentage for phage PSA-KC1 was 91.94%. Therefore, the newly discovered phage PSA-KC1 in this study is a novel bacteriophage. A phylogenetic tree for phage PSA-KC1 was constructed based on both the whole-genome and large terminase subunit sequences, which were closely related to other P. aeruginosa phages (Fig. 5A and B).

Evolutionary relationship of phage PSA-KC1 with other bacteriophages. (A) Phylogenetic trees of phage PSA-KC1 elicited from the whole-genome alignment generated by VipTree. (B) Phylogenetic trees were built using the terminase large subunit sequences of phage PSA-KC1 and related phages. Related protein sequences were downloaded from NCBI.

Prokka assigned a total of 65 predicted genes. On the basis of the BLASTp analysis results, 46 of the predicted gene products were assigned functions as structural proteins involved in genome replication, packaging, or phage lysis (Fig. 3, Table S1). The remaining predicted gene products were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The predicted functions of phage PSA-KC1 gene products based on BLASTp searches are detailed in Supplementary Table S1. No tRNA genes or antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) were detected in the phage PSA-KC1 genome. Additionally, no virulence factor-, toxin-, or integrase-related genes were found. Therefore, phage PSA-KC1 could be safely used for therapeutic phage therapy. In the phage PSA-KC1 genome, 41 rho-independent terminators were identified (Supplementary Table S2).

Transcription and replication genes

A BLASTp search for the gene products (Gps) of phage PSA-KC1 revealed putative annotations for 46 Gps, which are used as structural proteins, or enzymes involved in replication or translation. Gp22, Gp41, Gp42, and Gp43 are similar to DNA polymerases, whereas Gp44, Gp46 and Gp57 are predicted to be replicative clamp proteins, DNA helicases and DNA primases/helicases, respectively, all of which function in viral replication (Fig. 3). Gp01 of phage PSA-KC1 was annotated as an endonuclease. Both Gp47 and Gp52 of phage PSA-KC1 were annotated as recombinases. In general, exonucleases, DNA helicases and recombinases are related to the replication of phage genomes.

Lysis genes

Gp11 were predicted to be holin and Gp 5 and Gp12 were predicted to be endolysin. Gp13 was annotated as Rz as a span that spans the entire periplasm. G11 is a type II holin with two transmembrane domains. Transmembrane domains are between 21 and 46 and 58–76 amino acids. The G5 protein is 98.73% like the endolysin protein (YP_010597878.1) identified in the Pseudomonas phage BUCT-PX-5 genome. G12 is classified as a globular endolysin because it has a single CHAP (cysteine- and histidine-dependent amidohydrolase/peptidase) domain and these endolysins are common in bacteriophages that infect gram-negative bacteria. G13 is an Rz spanin protein containing outermembrane, transmebrane, and coil-containing cytoplasmic domains. These proteins are responsible for the final lysis of the host bacterium by the phage. Endolysins are hydrolytic enzymes of bacteriophages that hydrolyze cell walls during the terminal phase of the phage lytic cycle. Holins are small proteins that help initiate and control the degradation of bacterial cell walls, serving as a timing mechanism for cell lysis. Gp5, Gp11, Gp12, and Gp13 share 97%, 97%, 98% and 98% identity, respectively.

DNA packaging

The packaging of phage DNA into the head is mediated by the terminase complex, which consists of small and large terminase subunits (Gp14 and Gp15, respectively). A terminase identifies the cos domain of the phage genome to create sticky ends through ATP hydrolysis36. Along with phage portal proteins (Gp16), terminase initiates head assembly37. Terminase is a conserved protein found in double-stranded DNA phages, making terminase amino acid sequences useful for analyzing bacteriophage evolutionary relationships. A terminase-based phylogenetic tree (Fig. 5) demonstrated that phage PSA-KC1 is closely related to Pseudomonas phage vB Pae PS9N.

Head and tail morphogenesis and structural genes

Structural proteins are organized in the genome into two large clusters. The genes Gp23 to Gp31 and Gp35 have been identified as tail structural proteins, with the exception of Gp40. Gp27 is predicted to be a tail tape-measuring protein with 99% similarity to the major tail tube protein of Pseudomonas phage vB_PaeS_C1, which functions in injecting phage DNA into the phage head. Gp18 is also predicted to be an F-like head morphogenesis protein with 99% similarity to Pseudomonas phage vB_PaeS_SCUT-S4. Gp19 and Gp20 are annotated as scaffolding proteins, and Gp21 is designated the main capsid protein.

Phage activity against P. aeruginosa strains isolated from CF patients

Among the 25 P. aeruginosa strains isolated from CF patients, twenty-two (88%) were susceptible, and three strains (12%) were resistant to the Pyophage phage cocktail. Additionally, seventeen of the strains (68%) were susceptible, and eight strains (32%) were resistant to the phage PSA-KC1.

Discussion

The presence of a wide variety of phages in wastewater enables the isolation of bacteriophages specific to the pathogenic bacteria for phage therapy applications. In this study we isolated novel lytic phage PSA-KC1 effective against P. aeruginosa strains isolated from CF patients. Based on whole genome comparison, phage PSA-KC1, which belongs to Septimatrevirus genus, is a promising phage therapy agent as it kills 68% of 25 P. aeruginosa strains. Genomic characterization of the phage PSA-KC1 was performed by whole genome sequencing. It was confirm that there were no virulence factors, toxins, or integrase that would hinder their safe use in phage therapy. An annotation of the phage genome revealed 65 protein-coding genes. Of these, 46 predicted gene products have been assigned functions as structural proteins involved in genome replication, packaging or phage lysis.

Phages have several advantages over antibiotics. They are specific to certain types of bacteria, avoid secondary infection and resistance issues, and do not harm the normal microbiota. In contrast, antibiotics can lead to resistance problems and disrupt the balance of the entire microbiota, as they target al.l bacteria and have a limited impact on biofilms. Antibiotic-resistant infections result in significant financial losses, approximately $55–70 billion annually in the USA and over € 1.5 billion in Europe38.

Specific molecular interactions between the phage and host bacteria determine the host range of the bacteriophage. Both narrow and broad host range bacteriophages exist39. Bacteriophages specific to bacterial pathogens harvested from patients can be isolated from wastewater and use to treat infections. A Belgian CT consortium reported the successful application of personalized bacteriophage therapy with specific bacteriophages against pathogenic bacteria isolated from patients40.

CF patients are often infected with MDR P. aeruginosa strains. In various studies, treatment trials with phages have been performed in patients with cystic fibrosis. The efficacies of the PAK_P1, PAK_P2, PAK_P3, PAK_P4, PAK_P5, P3_CHA, CHA_P1, phiKZ, LBL3, and LUZ19 phage cocktails were tested in P. aeruginosastrains isolated from 48 patients with cystic fibrosis, with 64.6% reported to be sensitive to phages41. In our study, the pyophage phage cocktail was 88% effective, whereas the newly isolated PSA-KC1 phage was 68% effective. The PSA-KC1 phage was highly effective against MDR P. aeruginosa strains.

The susceptibility of P. aeruginosa strains isolated from 369 cystic fibrosis patients between 2007 and 2015 was evaluated by Rossitto, et al.42using the spot test method, with 88% of the strains found to be sensitive to phages42. The pyrophage cocktail failed to lyse 13 of 47 P. aeruginosa strains obtained from CF patients21. This finding is consistent with the effectiveness of our pyophage phage cocktail.

Lerdsittikul, et al.43 isolated the P. aeruginosa vB_PaeS_VL1 lytic phage from urban wastewater samples and reported that it was 56% effective against 60 multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa strains. They reported that this new phage could be a good candidate for phage therapy, as it lacks harmful genes such as antibiotic resistance genes and toxins. Compared to the P. aeruginosa vB_PaeS_VL1 phage, the novel phage PSA-KC1 has higher activity.

Wannasrichan, et al.44 reported that a new lytic P. aeruginosa JJ01 phage isolated from soil samples has 75% effectiveness against P. aeruginosa strains without containing any harmful genes, such as toxins, virulence or antibiotic resistance genes. Therefore, the P. aeruginosa JJ01 phage may be an excellent therapeutic candidate.

Chen, et al.45 isolated four new lytic phages against P. aeruginosa strains from hospital environments and various wastewaters. They reported that HX1 and MYY9 were 87.1% effective, MYY16 was 70.97%, and TH15 was 58.06% effective. YPT-01 phage therapy was applied to treat pulmonary infection caused by P. aeruginosain cystic fibrosis patients46.

Efficacy of commercial phage cocktails tested against P aeruginosa strains from patients with CF. In Kvachadze, et al.47, S. aureus and P. aeruginosa were isolated as bacterial agents in a cystic fibrosis patient. Pyophage cocktails and Sb-1 phage were used as treatment agents. Treatment with this phage cocktail was successful, resulting in a decrease in S. aureus and P. aeruginosa was observed. In the Zaldastanishvili, et al.48study, Pyohage and intestiphage treatment was applied in combination against P. aeruginosa, which was the causative agent of lung infection in a patient with CF, and was found to be successful. In another study, phage therapy was applied against MDR P. aeruginosa isolated as the causative agent of infection in patients with cystic fibrosis. Improvement in the clinic of patients and eradication of bacteria were observed49.

In our study, we observed that the PSA-KC1 phage had 68% effectiveness against MDR P. aeruginosa strains. Like the P. aeruginosa vB_PaeS_VL1 phage and P. aeruginosa JJ01 phage, the PSA-KC1 phage does not contain antibiotic resistance genes or toxin genes, making it a safe therapeutic candidate for phage therapy.

While the possibility of phage resistance exists, new phages can be discovered for target bacteria within a few weeks, unlike new antibiotics, which require a lengthy development process with uncertain success rates. Studies have not reported serious adverse effects of phages, but safety concerns still lead to concerns regarding phage therapy. However, the use of phage cocktails from phage banks without harmful genes can mitigate concerns such as excessive endotoxin release and gene transfer issues50,51,52,53.

There are few studies on phage therapy in Turkey, and our research, which includes genome sequence analysis of a phage for the first time in Turkey, can serve as a valuable resource for future comprehensive studies in the field. Focusing on discovering new phages is crucial, as they hold great potential for treating patients with MDR infections through phage therapy applications, especially for cystic fibrosis patients.

Since the PSA-KC1 phage does not contain virulence factors, toxins or integrase genes, it can be expected to be a therapeutic candidate with the potential to be used safely in phage therapy.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in GenBank Nucleotide Database at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OQ412632.

References

Venturini, C., Fabijan, P., Fajardo Lubian, A., Barbirz, A. & Iredell, J. S. Biological foundations of successful bacteriophage therapy. EMBO Mol. Med., e12435 (2022).

Chen, Q. et al. Bacteriophage and bacterial susceptibility, resistance, and tolerance to antibiotics. Pharmaceutics 14, 1425 (2022).

Furfaro, L. L., Payne, M. S. & Chang, B. J. Bacteriophage therapy: clinical trials and regulatory hurdles. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 8, 376 (2018).

Anand, T. et al. Phage therapy for treatment of virulent Klebsiella pneumoniae infection in a mouse model. J. Global Antimicrob. Resist. 21, 34–41 (2020).

Jeon, J., Park, J. H. & Yong, D. Efficacy of bacteriophage treatment against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in galleria Mellonella larvae and a mouse model of acute pneumonia. BMC Microbiol. 19, 1–14 (2019).

Morello, E. et al. Pulmonary bacteriophage therapy on Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis strains: first steps towards treatment and prevention. PloS One. 6, e16963 (2011).

Pouillot, F. et al. Efficacy of bacteriophage therapy in experimental sepsis and meningitis caused by a clone O25b: H4-ST131 Escherichia coli strain producing CTX-M-15. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 3568–3575 (2012).

Wang, J. et al. Use of bacteriophage in the treatment of experimental animal bacteremia from imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Mol. Med. 17, 309–317 (2006).

O’Sullivan, B. P. & Freedman, S. D. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet 373, 1891–1904. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60327-5 (2009).

Üstü, Y. & Uğurlu, M. National early diagnosis and Screenıng program: cystic fibrosis. Ankara Med. J. 16 (2016).

Alexander, B. et al. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry Annual Data Report (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, 2016).

Rafeeq, M. M. & Murad, H. A. S. Cystic fibrosis: current therapeutic targets and future approaches. J. Translational Med. 15, 1–9 (2017).

Riquelme, S. A., Wong Fok Lung, T. & Prince, A. Pulmonary pathogens adapt to immune signaling metabolites in the airway. Front. Immunol. 11, 385 (2020).

Chirgwin, M. E., Dedloff, M. R., Holban, A. M. & Gestal, M. C. Novel therapeutic strategies applied to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in cystic fibrosis. Materials 12, 4093 (2019).

Garcia-Clemente, M. et al. Impact of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection on patients with chronic inflammatory airway diseases. J. Clin. Med. 9, 3800 (2020).

Gündoğdu, A., Kılıç, H., ULU KILIÇ, A. & KUTATELADZE, M. Komplike Deri ve Yumuşak Doku Enfeksiyonu Etkeni Çoklu dirençli Patojenlerin Standart Bakteriyofaj Kokteyllerine Karşı Duyarlılıklarının Araştırılması. Mikrobiyoloji Bülteni. 50, 215–223 (2016).

Sahin, F., Karasartova, D., Ozsan, T. M., Gerçeker, D. & Kıyan, M. Identification of a novel lytic bacteriophage obtained from clinical MRSA isolates and evaluation of its antibacterial activity. Mikrobiyoloji Bulteni. 47, 27–34 (2013).

Harper, D. & Enright, M. Bacteriophages for the treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. J. Appl. Microbiol. 111, 1–7 (2011).

Vieira, A. et al. Phage therapy to control multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa skin infections: in vitro and ex vivo experiments. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 31, 3241–3249 (2012).

Law, N. et al. Successful adjunctive use of bacteriophage therapy for treatment of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in a cystic fibrosis patient. Infection 47, 665–668 (2019).

Essoh, C. et al. The susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from cystic fibrosis patients to bacteriophages. PLoS One. 8, e60575 (2013).

Villarroel, J., Larsen, M. V., Kilstrup, M. & Nielsen, M. Metagenomic analysis of therapeutic PYO phage cocktails from 1997 to 2014. Viruses 9, 328 (2017).

Manohar, P., Tamhankar, A. J., Lundborg, C. S. & Nachimuthu, R. Therapeutic characterization and efficacy of bacteriophage cocktails infecting Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Enterobacter species. Front. Microbiol. 10, 574 (2019).

Aydin, S. & Can, K. Pyophage cocktail for the biocontrol of membrane fouling and its effect in aerobic microbial biofilm community during the treatment of antibiotics. Bioresour. Technol. 318, 123965 (2020).

Kropinski, A. M. Practical Advice on the one-step Growth CurveVolume 341–47 (Methods and Protocols, 2018).

Ellis, E. L. & Delbruck, M. The growth of bacteriophage. J. Gen. Physiol. 22, 365–384 (1939).

Khan Mirzaei, M. & Nilsson, A. S. Isolation of phages for phage therapy: a comparison of spot tests and efficiency of plating analyses for determination of host range and efficacy. PLoS One. 10, e0118557 (2015).

Kyriakidis, I., Vasileiou, E., Pana, Z. D. & Tragiannidis, A. Acinetobacter baumannii antibiotic resistance mechanisms. Pathogens 10, 373 (2021).

Seemann, T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30, 2068–2069 (2014).

Arango-Argoty, G. et al. DeepARG: a deep learning approach for predicting antibiotic resistance genes from metagenomic data. Microbiome 6, 1–15 (2018).

Lowe, T. M. & Chan, P. P. tRNAscan-SE On-line: integrating search and context for analysis of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W54–W57 (2016).

Nishimura, Y. et al. Environmental viral genomes shed new light on virus-host interactions in the ocean. MSphere 2, e00359–e00316 (2017).

Lesnik, E. A. et al. Prediction of rho-independent transcriptional terminators in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 3583–3594 (2001).

Hofacker, I. L. et al. Fast folding and comparison of RNA secondary structures. Monatshefte Für Chemie/Chemical Monthly. 125, 167–188 (1994).

Gautheret, D. & Lambert, A. Direct RNA motif definition and identification from multiple sequence alignments using secondary structure profiles. J. Mol. Biol. 313, 1003–1011 (2001).

Duffy, C. & Feiss, M. The large subunit of bacteriophage Λ’s terminase plays a role in DNA translocation and packaging termination. J. Mol. Biol. 316, 547–561 (2002).

Casjens, S. R. The DNA-packaging nanomotor of tailed bacteriophages. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 647–657 (2011).

Li, B. & Webster, T. J. Bacteria antibiotic resistance: new challenges and opportunities for implant-associated orthopedic infections. J. Orthop. Research®. 36, 22–32 (2018).

de Jonge, P. A., Nobrega, F. L., Brouns, S. J. & Dutilh, B. E. Molecular and evolutionary determinants of bacteriophage host range. Trends Microbiol. 27, 51–63 (2019).

Pirnay, J. P. et al. Personalized bacteriophage therapy outcomes for 100 consecutive cases: a multicentre, multinational, retrospective observational study. Nat. Microbiol., 1–20 (2024).

Saussereau, E. et al. Effectiveness of bacteriophages in the sputum of cystic fibrosis patients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 20, O983–O990 (2014).

Rossitto, M., Fiscarelli, E. V. & Rosati, P. Challenges and promises for planning future clinical research into bacteriophage therapy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. An argumentative review. Front. Microbiol. 9, 775 (2018).

Lerdsittikul, V. et al. A novel virulent litunavirus phage possesses therapeutic value against multidrug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–16 (2022).

Wannasrichan, W. et al. Phage-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa against a novel lytic phage JJ01 exhibits hypersensitivity to colistin and reduces biofilm production. Front. Microbiol. 13 (2022).

Chen, F. et al. Novel lytic phages protect cells and mice against pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. J. Virol. 95, e01832–e01820 (2021).

Stanley, G. et al. In C107. MICROBIAL RESPIRATORY INFECTIONS DISCOVERIES A6808-A6808 (American Thoracic Society, 2024).

Kvachadze, L. et al. Evaluation of lytic activity of Staphylococcal bacteriophage Sb-1 against freshly isolated clinical pathogens. Microb. Biotechnol. 4, 643–650 (2011).

Zaldastanishvili, E. et al. Phage therapy experience at the Eliava phage therapy center: three cases of bacterial persistence. Viruses 13, 1901 (2021).

Stanley, G. et al. In B29. INFECTION AND IMMUNE INTERPLAY IN LUNG INJURY A2977-A2977 (American Thoracic Society, 2020).

Dufour, N., Delattre, R., Ricard, J. D. & Debarbieux, L. The Lysis of pathogenic Escherichia coli by bacteriophages releases less endotoxin than by β-lactams. Clin. Infect. Dis. 64, 1582–1588 (2017).

Loc-Carrillo, C. & Abedon, S. T. Pros and cons of phage therapy. Bacteriophage 1, 111–114 (2011).

Moelling, K., Broecker, F. & Willy, C. A wake-up call: we need phage therapy now. Viruses 10, 688 (2018).

Sulakvelidze, A., Alavidze, Z. & Morris, J. G. Jr Bacteriophage therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 649–659 (2001).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the financial support from IUC-BAP 34517 (Istanbul University-Cerrahpasa, BAP).The study was approved by the İstanbul University-Cerrahpasa, Cerrahpasa Medical Faculty, Clinical Research Ethics Committee (83045809-604.01.02). All methods are conducted in compliance with relevant guidelines and regulations.Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.C. conceived and designed the study. E.T., D.O. and D.N.A. performed the research under the guidance of K.C. S.A. provided technical support and analyzed the data. H.K. analyzed sequencing data. K.C. and H.K. wore the manuscript. M.S., N.G. and H.B.T. provided critical support and helped in drafting of the paper. All the authors revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kurt, K.C., Kurt, H., Tokuç, E. et al. Isolation and characterization of new lytic bacteriophage PSA-KC1 against Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Sci Rep 15, 6551 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91073-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91073-1