Abstract

The analysis of unperturbed tumor growth kinetics, particularly the estimation of parameters for S-shaped equations used to describe growth, requires an appropriate likelihood function that accounts for the increasing error in solid tumor measurements as tumor size grows over time. This study aims to propose suitable likelihood functions for parameter estimation in S-shaped models of unperturbed tumor growth. Five different likelihood functions are evaluated and compared using three Bayesian criteria (the Bayesian Information Criterion, Deviance Information Criterion, and Bayes Factor) along with hypothesis tests on residuals. These functions are applied to fit data from unperturbed Ehrlich, fibrosarcoma Sa-37, and F3II tumors using the Gompertz equation, though they are generalizable to other S-shaped growth models for solid tumors or analogous systems (e.g., microorganisms, viruses). Results indicate that error models with tumor volume-dependent dispersion outperform standard constant-variance models in capturing the variability of tumor measurements, particularly the Thres model, which provides interpretable parameters for tumor growth. Additionally, constant-variance models, such as those assuming a normal error distribution, remain valuable as complementary benchmarks in analysis. It is concluded that models incorporating volume-dependent dispersion are preferred for accurate and clinically meaningful tumor growth modeling, whereas constant-dispersion models serve as useful complements for consistency and historical comparability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Understanding tumor growth kinetics (TGK) is a challenging aspect of untreated cancer biology. Even though Bru et al.1reported that untreated tumors grow linearly, other studies suggest that tumor growth is inherently nonlinear. Most experimental studies reveal that TGK follows a sigmoidal (S-shaped) rather than exponential pattern, as observed across various tumor types in different hosts, independently of the tumor formation pathway (e.g., cell inoculation, solid tumor transplantation, or induction by carcinogenic agents)2,3,4,5,6. Different S-shaped mathematical models, particularly those based on ordinary differential equations (ODEs), have been used to describe TGK. These include power-law, Richards, Weibull, von Bertalanffy, von Bertalanffy-Pütter type, Verhulst (Logistic), and conventional Gompertz equations1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Additionally, models such as the Kolmogorov-John-Mell-Avrami10, modified Kolmogorov-John-Mell-Avrami10and Montijano-Bergues-Bory-Gompertz11equations have also been applied to describe unperturbed TGK. Other models12,13,14have been proposed and recent advancements also explore fractional-order ODEs15,16,17,18,19 to model tumor growth dynamics.

The consensus of authors is that the conventional Gompertz equation shows superior performance in fitting experimental data compared to other models4,5,10,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. Logistic and von Bertalanffy equations often fail to capture tumor growth data accurately, but several alternative models, including the Gompertz14, have been effective for describing tumor growth dynamics in specific contexts. Nevertheless, those two models adequately described human tumor growths4. For instance, Ghaffari Laleh et al.29 demonstrated that the general von Bertalanffy and conventional Gompertz equations yielded the lowest mean absolute errors in forecasting tumor growth across 1,472 patients with three or more data points.

Other studies have compared power-law, Logistic, conventional Gompertz, exponential, and von Bertalanffy equations across data from 10 tumor types30. The results revealed that the power-law, Logistic, and conventional Gompertz equations best described TGK in six, three, and one tumor types, respectively. Conversely, von Bertalanffy (in seven tumor types) and exponential (in three tumor types) models deviated significantly from experimental data. Furthermore, Valentim et al.15 showed that non-integer order models (e.g. Conventional Gompertz, exponential, von Bertanlanffi and Guiott-West models) consistently described experimental data better than their integer-order counterparts in G1-101A human breast cancer cells transplanted into nude mice.

The performance of different models depends on factors such as the tumor growth phase and data range. For example, early tumor growth stages (exponential phase)10,31are best captured by fractional or integer exponential models4,5,7,8,10,11,14,31,32,33,34,35, whereas other models perform poorly for time points beyond 80 days. Additionally, the fractality11,32,36,37,38,39, heterogeneity40, and viscoelasticity41,42 of tumors may explain why fractional-order models often outperform integer-order counterparts. Notably, some models, like von Bertalanffy-Pütter, are more suitable for short time spans (e.g. \(t<10\)days)9.

These findings highlight three key points: 1) No single ODE-based model is universally accepted as the most appropriate for all cancer types or histological subtypes. 2) Incorrect model selection can lead to parameter estimation inaccuracies and unreliable oncological predictions. 3) Although statistical metrics often favor one model over others for specific experimental conditions, these differences are sometimes negligible10,35, suggesting that multiple models can be used interchangeably for the same histological subtype in a given host.

From an experimental point of view, this may mean that these models may be used interchangeably to fit data for the histological variety growing in a given host. All S-shaped equations reported in the literature may be related to each other by establishing analytical relationships between their parameters, following the methodology reported in32. Therefore, any of these equations, in principle, may be used interchangeably in the fitting of experimental data. As Gompertz formulations are fractal in nature10,11,32, this correspondence between S-shaped equations may suggest that all these equations are also fractal in nature.

In most of the above studies, the possible errors in the data are not considered or they are supposed to follow a Normal distribution. Nevertheless, in vitro7,43, preclinical7,8,10,11,33,34,35,44and clinical45studies show that measurement errors tend to increase with tumor volume, especially during transitions from the avascular (spherical) to the vascular (ellipsoidal) phase of TGK. This increased error likely arises from irregularities in tumor edges, spatial and temporal variations in blood vessel distribution, and tumor heterogeneity and anisotropy10,11,31,35,42,46,47. These observations raise a critical question: Should Gompertz model parameter estimation explicitly account for the increasing measurement errors during TGK, or should the model aim to fit the data as closely as possible without considering error variability? Addressing this issue necessitates selecting an appropriate likelihood function for model fitting, whether using classical maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) or Bayesian approaches. Different strategies have been employed to address this challenge. Some studies rely on least-squares fitting without reference to a likelihood function, often implicitely assuming constant Gaussian errors, which also reduces to a least-squares fit under the MLE paradigm48,49,50. Others model error variability by using normal distributions with dispersion proportional to tumor volume51,52, requiring algorithms like Nelder-Mead7,53for fitting instead of least-squares-based methods like Levenberg-Marquardt. The Student-t distribution, known for its robustness to outliers54, also presents a promising alternative for modeling tumor measurement errors, as demonstrated in recent applications to COVID-19 data55. Despite differences between TGK and epidemic growth, several models are applicable to both domains.

In this paper, we analyze the impact of measurement errors on the estimation of standard Gompertz model parameters. Specifically, we compare five likelihood functions based on different error models: Normal with constant standard deviation (Norm), Normal with standard deviation proportional to tumor volume (Norm prop), Normal with a constant standard deviation below a threshold volume \(V_m\) and proportional standard deviation above it (Thres), Student-t with constant standard deviation (Stud) and Student-t with standard deviation proportional to tumor volume (Stud prop).

These likelihood functions are evaluated using Bayesian criteria, namely the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), Deviance Information Criterion (DIC), and Bayes Factor (BF). To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive comparison of these error models, aiming to guide the selection of the most suitable approach for tumor growth analysis.

Methods

Models

As the main intention of this study is not to compare S-shaped models, but the different error models represented by likelihood functions, we select one of these S-shaped models to fit experimental data in solid tumors with different likelihood functions for the errors. We take the standard Gompertz equation based on the consensus of authors to describe unperturbed TGK1,4,5,8,10,11,31,35) and because this equation gives a very reasonable fitting in all cases, although it does not give the best fitting results for some tumor types. Note that the analysis we are presenting can be applied to any other tumor growth model.

The Gompertz growth model can be expressed in several parameterizations, classified as type I and type II based on their shape parameters56. We posit that the modified type-II model, which incorporates observable tumor volume, offers the most clinically interpretable parameters11. Although any parametrization is theoretically viable for likelihood comparison, the type-I Gompertz model is employed here for its simplicity. In this model, the tumor volume V(t) at time t is a function of the negative logarithm of the initial tumor volume V(0) divided by the carrying capacity (K), expressed as

where \(r> 0\) represents the growth rate. This formulation of Gompertz growth has the practical advantage of simplifying the estimation of Kdue to its direct relationship with the data trends. As V(t) is a consequence of all the complex interactions that occur in the tumor and those between the tumor, as a whole, and the rest of the organism8,10,11,31,35, equation 1 is sufficient for the intention of this study.

The individual observation model is defined as

where \(y_{i}\) denotes the measured tumor volume for the individual at time \(t_i\), \(f(t_i; \theta )\) is the Gompertz model evaluated at time \(t_i\), \(\theta =(r, K, V(0))\) is the vector of Gompertz model parameters, \(e_i\) is the model error for observation \(y_i\), N is the number of measurements and M is the number of individuals in the experiment.

Since we are interested in the effect of the errors \(e_i\)on the computations of the parameters, we focus on individual datasets to isolate and accurately model tumor-specific measurement errors, which often depend on tumor size and shape irregularities. In this way the results will not be affected by the random inter-subject variability of the parameters of the equation, avoiding possible biases. Thus, we do not use the mixed effect model approach57,58 in this study. We are also assuming that the errors in measurement follow the same distribution e for any individual, and depend only on the size of the tumor at time \(t_j\), \(e=e(t_j)\).

We now describe the five \(e_i\) expressions used to compare different likelihood functions. The first error model is the standard Normal error with constant standard deviation (\(\sigma\)), given by

This error model and its corresponding likelihood function are referred to as Norm. The Norm model produces parameter estimates equivalent to the least-squares approach59..

The second error model, named Prop, posits that the standard deviation of the Normal distribution is proportional to the measured volume, formulated as

The third error model, designated as Thres, alters its law based on a threshold \(V_m\)of the measured volume51, and is described by

The rationale for this model is that, in a previous study, volume-independent standard deviation was statistically rejected, and proportional error demonstrated limited significance in Lewis lung carcinoma and breast cancer data51. Additionally, the Bayesian estimation of \(\alpha\) and \(V_m\) in this model is an innovative aspect of our work.

The fourth error model, named Stud, employs the Student-t distribution with a fixed degree-of-freedom parameter (v) and constant dispersion, and can be expressed as

Lastly, the fifth error model, Stud Prop, resembles the fourth but includes dispersion proportional to the measured volume as

The likelihood functions are obtained by treating each observation as independent realization of the error model and multiplying individual likelihood contributions.

Model comparison

We use three Bayesian criteria for model comparison. The first is the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC)60, defined as

where k is the number of model parameters, and \({\widehat{L}}\) is the maximized value of the likelihood function for the model.

Let us denote the likelihood of \(y_i\) under model j by \(P(y_i \mid \theta _j, M_j)\) and the posterior expectation of \(\theta\) by \(\bar{\theta }\). The second criterion is the Deviance Information Criterion (DIC)61, calculated as

where \(D(\theta ) = -2\log (P(y_i \mid \theta _j, M_j))\), \(\overline{D(\theta )}\) is the posterior expectation of \(D(\theta )\) and \(p_D = \overline{D(\theta )} - D(\bar{\theta })\). Models with lower BIC and DIC values are preferable.

Although BIC is a consistent criterion and decisive when the correct model is among the candidates, it tends to heavily penalize free parameters60,62. Meanwhile, DIC is limited by its assumption of an approximately multivariate normal posterior distribution61, which has not been verified for the models in this study. Furthermore, DIC inconsistency and reparametrization variance limit its applicability61, as does its tendency to favor short-term prediction accuracy over model selection63. Therefore, DIC is accorded less weight in our model selection process.

The third criterion is the Bayes Factor (BF), representing the marginal likelihood (ML) ratio between two competing models (\(M_j\), \(M_k\)), whose general expression is

where \(P(\theta _j \mid M_j)\) is the prior distribution of the parameters for model j. The sensitivity of the BF to prior distributions, particularly with weak prior information, is a noted issue64,65.

To mitigate this, we use the Fractional Bayes Factor (FBF)66 with training fraction \(0<b<1\) as

where

Here, \(q_j(y_i; b)\) represents a quantity similar to the marginal likelihood \(ML(y_i; M_j)\), but where a fraction of the data, b, is used to reduce the sensitivity of the marginal likelihood to the choice of prior distribution66. We focus on the marginal likelihood (and \(q_j(y; b)\)) in our analysis. To compute the integrals in equation (12), we employ thermodynamic integration67using 30 temperature values between 0 and 1, implemented via the delayed-rejection adaptive Metropolis (DRAM) algorithm68. The Monte Carlo chain initialization for DRAM is based on results from the dual simulated annealing algorithm69. Uniform distributions \(P(\theta _j \mid M_j) \sim U(0,\infty )\) are used as improper priors for the parameters, except for \(\sigma\), which follows a normal distribution centered on the value computed by the dual simulated annealing algorithm with 10% standard deviation69.

The fractional Bayes factor (FBF) approach does not impose assumptions about the prior and instead adjusts it using a subset of the data, offering greater robustness compared to methods applying penalizing terms in the mathematical formulation70. Nevertheless, the selection of bcan introduce bias71. In this study, \(b = 0.04\) was selected based on the following considerations:

-

Balancing Prior Influence and Data Sensitivity: A goal in the choice of b is to use as small proportion of the data as possible to adequately modify the prior, while leaving as much data as possible to compute the marginal likelihood. Through an exploration of various b values across individuals, \(b=0.04\) was identified as an effective compromise, yielding robust marginal likelihood estimates without sacrificing too much data.

-

Empirical Evaluation Across Models: Empirical assessments supported the choice of \(b=0.04\), which produced stable marginal likelihood estimates and consistent model comparisons across various error structures. This value effectively facilitated meaningful evaluations of competing likelihood models for most individuals in the dataset.

-

Mitigating Computational Bias: Larger b values can overemphasize prior information, in that less data is used to compute the marginal likelihood, introducing artifacts, especially in cases of high data variability. Conversely, extremely small b values may lead to unreliable model assessments, due to not adequately modifying the prior. The selected \(b=0.04\) avoided these pitfalls, ensuring stability and reliability during thermodynamic integration.

Cases where \(b = 0.04\)failed to produce reliable marginal likelihood estimates (less than 5% of the total cases) were excluded from the analysis. This exclusion did not affect the final conclusions, as the analysis focused exclusively on individuals with reliably calculated marginal likelihoods. Additionally, we performed Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) tests72 on the posterior-drawn residuals to check how well they align with each model’s implied distribution. Let \(\theta ^{(\ell )}\) denote the \(\ell\)-th sample from the posterior distribution (\(\ell = 1,\dots ,N_\ell\)), and define

For each model, we test the following sets of residuals against the corresponding theoretical distribution:

-

Norm model: \(\{R_i^{(\ell )}\}\) against the normal distribution.

-

Prop model: \(\bigl \{R_i^{(\ell )}/y_i\bigr \}\) against the normal distribution.

-

Thres model: \(\bigl \{R_i^{(\ell )}/E_i\bigr \}\) against the normal distribution, where \(E_i\) is given in equation (5).

-

Stud model: \(\{R_i^{(\ell )}\}\) against the Student-\(t\) distribution.

-

Stud Prop model: \(\bigl \{R_i^{(\ell )}/y_i\bigr \}\) against the Student-\(t\) distribution.

For each individual, we then compute the fraction of KS tests (across all posterior draws) that do not reject the null hypothesis for that model, denoted as \(\text {fr(KS)}\).

For model comparison, we use experimental volume data from datasets of unperturbed Ehrlich and fibrosarcoma Sa-37 tumors growing in male BALB/c/Cenp mice8, and unperturbed F3II mammary carcinoma (highly aggressive and metastatic) growing in both female and male BALB/c/Cenp mice33. Datasets in F3II mammary carcinoma-bearing male and female BALB/c/Cenp mice are analyzed separately.

The data were provided by Dr. Luis Enrique Bergues Cabrales, head of the Bioelectricity group, Centro Nacional de Electromagnetismo Aplicado, Universidad de Oriente and are available at https://github.com/eramireztorres/tumor_error_model. Simulations were conducted using Python 373, specifically the scipy.optimize74 and pymcmcstat75 packages, on a 4-core high-performance computing (HPC) system with 256 GB of RAM at the Instituto Universitario de Matemáticas y Aplicaciones (IUMA), Universidad de Zaragoza, Spain.

Results

In Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4 (see Appendix), we present the model fit indicators for each individual in the unperturbed Ehrlich tumor dataset, highlighting the best results in bold. The Stud Prop model consistently provides the best results for the BIC indicator across all individuals. For the DIC indicator, the Thres model performs best for seven individuals, whereas the Norm model leads for the remaining three. Regarding ML, the Prop model is optimal for one individual, the Norm model for five, and the Stud model for four. For fr(KS), the Prop, Thres, and Stud Prop models excel for 3, 5, and 2 individuals, respectively.

Even though these results prevent us from concluding that one model is superior to the others, they show clearly that models with variable dispersion (Prop,Thres and Stud Prop) are markedly better than constant dispersion models (Norm and Stud), particularly for fr(KS). This suggests that likelihoods with variable dispersion are better suited to modeling errors in tumor growth studies. No significant gender-based differences were observed in the results.

For the unperturbed fibrosarcoma Sa-37 tumor dataset (Tables 5, 6, 7 and 8), variable dispersion models show clear superiority in BIC and fr(KS). Nevertheless, DIC and ML results are split evenly across individuals. In the unperturbed F3II mammary carcinoma dataset for male BALB/C/Cenp mice (Tables 9, 10, 11 and 12), variable dispersion models outperform in DIC and fr(KS), whereas results are close for BIC and ML (6 individuals vs. 5). Similarly, in female BALB/C/Cenp mice (Tables 13, 14, 15 and 16), variable dispersion models yield better outcomes for all indicators: BIC, DIC, ML, and fr(KS).

Tables 17, 18, 19 and 20 summarize average results across all individuals. These tables were constructed by taking the arithmetic mean of each model criterion (BIC, DIC, ML, fr(KS)) across all individuals in the respective dataset. The averages reveal varied performance across models. For the unperturbed Ehrlich (Table 17) and fibrosarcoma Sa-37 datasets (Table 18): The Thres model demonstrates the best mean DIC and fr(KS) values. The Stud Prop and Norm models excel in mean BIC and ML, respectively. For the unperturbed F3II mammary carcinoma dataset (Tables 19 and 20): The Prop model excels in mean BIC and fr(KS). The Thres model leads in mean DIC. The Norm model (male mice) and Prop model (female mice) are best in mean ML. These results support the conclusion that adding variable dispersion likelihood to mixed-effects models is an excellent approach for estimating tumor growth model parameters.

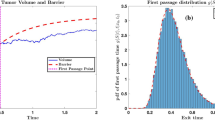

In terms of prediction accuracy, all models demonstrated comparable performance to individual 1 from the unperturbed fibrosarcoma Sa-37 tumor dataset, a trend consistent across all four histological tumor types. The Prop, and Thres models exhibited greater variability in the prediction cone, represented by the 95% credible intervals of posterior trajectories, yet the maximum a posteriori (MAP) trajectory closely aligned with the observed data in all five models (Figure 1).

Discussion

The comparison criteria and visualisations of model fits reveal no definitive best model. To determine priorities, we analyze the advantages and limitations of each criterion and explore clinical implications.

Since the BIC heavily penalizes the number of model parameters, it naturally favors the simpler models. Its value would be decisive if for some data it favored the more complex model. This is not the case here, because a simple model is always favored by BIC, as expected, and never the Thres model, which is the most complex one. Nevertheless, for some particular datasets, the Thres model yields better BIC values than other simpler models. For instance, the third individual from the Ehrlich tumor data (Table 1) demonstrates this. It indicates that, for the BIC, the complexity introduced by the additional parameters of the Thres model (\(\alpha\) and \(V_m\)) is justified by the quality of the fit. This finding, along with the relatively good DIC values (Table 2) and fr(KS) values (Table 4) it achieves, supports recommending the Thres model. Another advantage of the Thres model is in the clinical interpretability of it’s parameters. For example, the parameter \(V_m\) could represent the threshold tumor volume at which the surface/contour begins to become irregular, or where tumor growth becomes irreversible, with or without anticancer therapy (either oncospecific or under study). Experimental observations indicate that tumor surfaces become irregular from 2.0 \(cm^3\)8,32,37,76. Nevertheless, regulatory and ethical considerations for laboratory experiments with animals10,11,34,35prevent the measurement of tumor volume when it exceeds 10% of body weight. This must be considered in all experimental and similar studies. The differences in ML values obtained may be categorized as anecdotal77.

A major concern is fr(KS), for which very small values are observed for constant-dispersion models. The Norm and Stud models show zero values for several individuals (see Tables 4, 8, 12 and 16). This indicates that very few or no trajectories drawn from the posterior generate residuals with non-rejected KS tests. This surprising result challenges the use of the two constant-dispersion models assessed and suggests revisiting the entire constant-dispersion paradigm in the absence of information to the contrary. Based solely on quantitative criteria, our results suggest that the Norm model is not the best to fit Gompertz growth.

This raises an important question: what are the clinical implications of introducing variable-dispersion errors instead of traditional least-squares fitting? The first consequence is that predictions accounting for variable-dispersion errors are more likely to indicate actual tumor volumes exceeding measured volumes. Second, standard cancer therapies based on closely fitting models to data may require theoretical reformulation. Nevertheless, we do not recommend discarding the Norm model entirely, as it is widely used in existing research and serves as a baseline for evaluating cancer therapy improvements. We believe that the best option is always to apply the Norm model in the model fits, either with the least-squares approach or the Bayesian approach, and complement it with an estimation of variable dispersion.

Although we argue that the Gompertz model remains preferable for modeling most solid tumors, it’s appropriateness or otherwise does not undermine the applicability of our results. This is because Gompertz growth is used only in the deterministic component of the model. Measurement challenges, such as unsharp boundaries and irregular tumor shapes, persist in clinical practice regardless of the deterministic growth model.

To resolve the likelihood dilemma, we propose that studies should include the Norm model to ensure compatibility with previous results. Nevertheless, at least one model with variable dispersion should also be included for a more realistic representation of tumor size. Both approaches should complement each other. We recommend the Thres model but suggest the Prop or Stud Prop models for researchers seeking reduced computational complexity.

Although the Gompertz growth model was used to fit experimental tumor data from mice, its generalizability to clinical practice requires careful evaluation. Studies have shown that Gompertzian growth can describe human tumor kinetics in specific cases, such as the foundational work by Skipper et al.78 and patient-specific findings by Grassberger et al.79. Nevertheless, alternative growth patterns, such as near-linear growth for certain tumor types and stages80, have been observed. Kidney tumors under active surveillance exemplify this, with smaller tumors exhibiting near-linear growth81,82and Gompertzian dynamics emerging in long-term studies6. This variability supports including models like the Bertalanffy model, which provides biologically motivated alternatives that converge to similar growth trajectories83.

Importantly, even though the Gompertz model was used as the deterministic component in our analysis, the conclusions of our study are not model-dependent. The deterministic growth function interacts with the likelihood and error models only to generate predicted data for comparison with observations. Measurement challenges-such as irregular tumor shapes, unsharp boundaries, and imaging variability-are pervasive in both experimental and clinical settings and are independent of the underlying deterministic model. These challenges underscore the critical role of appropriate likelihood models, as our results demonstrate that error model selection significantly affects parameter estimation and predictive accuracy.

To address these challenges, we propose a dual likelihood modeling approach. The Norm model should remain a baseline to ensure compatibility with previous studies, but incorporating a likelihood model that accounts for variable dispersion is essential for capturing tumor heterogeneity. Our results highlight the suitability of Thres model, as it balances robustness and interpretability. For researchers seeking less computational complexity, the Prop or Stud Prop models provide viable alternatives, improving realism over the Norm model. This complementary use of baseline and advanced likelihood models ensures reproducibility and accommodates the increasing complexity of tumor growth dynamics.

Advantages of the proposed methodology

The methodology presented in this study offers significant advancements over existing approaches for modeling tumor growth dynamics. Unlike many published methods that rely on fixed error models or likelihood functions, our approach systematically evaluates multiple likelihood models, including those that account for variable dispersion. This flexibility allows for a more accurate representation of tumor heterogeneity and measurement variability, which are critical factors in understanding cancer progression84.

In addition, the incorporation of diverse growth models, such as Gompertz and Bertalanffy, enables the application of our methodology to a wide range of tumor types and stages. This adaptability is essential for addressing the variability observed in experimental and clinical tumor growth data51.

The method also addresses practical challenges in tumor measurement, such as irregular shapes, unsharp boundaries, and imaging inconsistencies, making it particularly relevant for real-world applications. Furthermore, the detailed computational pipeline and open-source implementation ensure reproducibility, allowing other researchers to replicate and extend our findings effectively.

These features establish the proposed methodology as a robust and versatile tool for studying tumor growth dynamics, complementing and extending the capabilities of existing approaches in the field.

Limitations of the proposed methodology

Despite the significant advancements it brings, the proposed methodology does have some limitations. First, the selection of growth and likelihood models depends on the availability and quality of data. In scenarios where limited data points are available, model overfitting may occur, potentially affecting the reliability of predictions.

Second, although our approach integrates Bayesian and Frequentist (by KS test) methods to enhance robustness, the computational complexity of Bayesian analysis, particularly with multiple b-values, can be resource-intensive. This may limit its applicability in high-throughput scenarios without access to sufficient computational resources.

Finally, the approach has been only validated on specific tumor types and datasets; nevertheless, its adaptability to other datasets and generalizability to other cancer types, particularly those with non-solid growth dynamics, should be fully explored. Future studies could address these limitations by incorporating broader datasets, testing additional tumor types, and improving computational efficiency through optimized algorithms.

Conclusions

Our analysis highlights the advantages of variable dispersion error models over constant variance models. Although none of the three models (Prop, Thres, Stud Prop) consistently excels, the Thres model emerges as a robust choice for most scenarios, with solid performance across criteria and meaningful clinical interpretability. In any case, our results indicate that the standard constant-variance Normal error model should remain part of the analysis toolkit, to provide a complementary analytic reference in addition to more flexible error models.

Finally, although the Gompertz model was employed as the deterministic component, our conclusions remain valid regardless of the specific growth model used. Incorporating both constant and variable dispersion likelihoods offers a balanced approach for future tumor growth modeling studies.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study as well as the phyton code are available at https://github.com/eramireztorres/tumor_error_model.

References

Brú, A., Albertos, S., Subiza, J. L., García-Asenjo, J. L. & Brú, I. The universal dynamics of tumor growth. Biophysical journal 85, 2948–2961 (2003).

Steel, G. Growth kinetics of tumours. Cell Population Kinetics in Relation to the Growth and Treatment of Cancer (Clarendon press, Oxford, 1977).

Fu, K. K. & Steel, G. Growth kinetics of a rat mammary tumour transplanted into immune-suppressed mice. Cell Proliferation 12, 493–499 (1979).

Vaidya, V. G. & Alexandro, J. F. Evaluation of some mathematical models for tumor growth. Int J Biomed Comput 13, 19–35 (1982).

Marušić, M. Mathematical models of tumor growth. Mathematical Communications 1, 175–88 (1996).

Crispen, P. L. et al. Natural history, growth kinetics, and outcomes of untreated clinically localized renal tumors under active surveillance. Cancer 115, 2844–2852 (2009).

Benzekry, S., Beheshti, A., Hahnfeldt, P. & Hlatky, L. Capturing the driving role of tumor-host crosstalk in a dynamical model of tumor growth. Bio-protocol 5 (2015).

Cabrales, L. et al. Mathematical modeling of tumor growth in mice following low-level direct electric current. Math. Simul. Comp. 78, 112–120 (2008).

Kühleitner, M., Brunner, N., Nowak, W. G., Renner-Martin, K. & Scheicher, K. Best fitting tumor growth models of the von Bertalanffy-PütterType. BMC cancer 19, 1–11 (2019).

González, M. M. et al. Is cancer a pure growth curve or does it follow a kinetics of dynamical structural transformation?. BMC cancer 17, 1–14 (2017).

Castañeda, A. R. S. et al. New formulation of the Gompertz equation to describe the kinetics of untreated tumors. PloS one 14, e0224978 (2019).

Ribatti, D. & Pezzella, F. Overview on the different patterns of tumor vascularization. Cells 10, 639 (2021).

Sachs, R. K., Hlatky, L. R. & Hahnfeldt, P. Simple ode models of tumor growth and anti-angiogenic or radiation treatment. Mathematical and Computer Modelling 33, 1297–1305 (2001).

Marušić, M., Vuk-Pavlovic, S. & Freyer, J. P. Tumor growth in vivo and as multicellular spheroids compared by mathematical models. Bulletin of mathematical biology 56, 617–631 (1994).

Valentim, J. C. A., Oliveira, N. A., Rabi, J. A. & David, S. A. Can fractional calculus help improve tumor growth models?. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics 379, 112964 (2020).

Frunzo, L., Garra, R., Giusti, A. & Luongo, V. Modeling biological systems with an improved fractional Gompertz law. Commun Nonlinear Sci Numer Simulat 74, 260–267 (2019).

Sabir, Z. et al. Numerical investigations of the fractional-order mathematical model underlying immune-chemotherapeutic treatment for breast cancer using the neural networks. Fractal Fract. 6, 184 (2022).

Valentim, C. A., Rabi, J. A., A., D. S. & Machado, J. A. T. On multistep tumor growth models of fractional variable-order. BioSystems 199, 104294 (2021).

Hassani, H., Tenreiro Machado, J. A., Avazzadeh, Z., Safari, E. & Mehrabi, S. Optimal solution of the fractional order breast cancer competition model. Scientifc Reports 11, 15622 (2021).

Durbin, P. W. et al. Construction of a growth curve for mammary tumors of the rat. Cancer Research 27, 1341–1347 (1967).

Simpson-Herren, L. & Lloyd, H. H. Kinetic parameters and growth curves for experimental tumor systems 1, 2. Cancer Chemotherapy Reports 54, 143 (1970).

Steel, G. & Lamerton, L. The growth rate of human tumours. British journal of cancer 20, 74 (1966).

Xu, X. The biological foundation of the Gompertz model. International journal of bio-medical computing 20, 35–39 (1987).

Speer, J. F., Petrosky, V. E., Retsky, M. W. & Wardwell, R. H. A stochastic numerical model of breast cancer growth that simulates clinical data. Cancer Research 44, 4124–4130 (1984).

Vaghi, C. et al. Population modeling of tumor growth curves and the reduced gompertz model improve prediction of the age of experimental tumors. PLoS computational biology 16, e1007178 (2020).

Oberg, A. L. et al. Statistical analysis of comparative tumor growth repeated measures experiments in the ovarian cancer patient derived xenograft (PDX) setting. Scientific reports 11, 8076 (2021).

Voulgarelis, D., Bulusu, K. C. & Yates, J. W. Comparison of classical tumour growth models for patient derived and cell-line derived xenografts using the nonlinear mixed-effects framework. Journal of Biological Dynamics 16, 160–185 (2022).

Jarrett, A. et al. Mathematical models of tumor cell proliferation: a review of the literature. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy 18, 1271–1286 (2018).

Ghaffari, L. N. et al. Classical mathematical models for prediction of response to chemotherapy and immunotherapy. PLoS computational biology 18, e1009822 (2022).

Sarapata, E. & de Pillis, L. G. A comparison and catalog of intrinsic tumor growth models. Bull Math Biol 76, 2010–2024 (2014).

Cabrales, L. et al. Modified Gompertz equation for electrotherapy murine tumor growth kinetics: Predictions and new hypotheses. BMC Cancer 10, 589–599 (2010).

Goris, N. et al. Correspondence between formulations of Avrami and Gompertz for untreated tumor growth kinetics. Rev Mex FÃs 66, 632–636 (2020).

Ciria, H. et al. Antitumor effectiveness of different amounts of electrical charge in Ehrlich and fibrosarcoma Sa-37 tumors. BMC cancer 4, 1–10 (2004).

González, M. M. et al. Dose-response study for the highly aggressive and metastatic primary F3II mammary carcinoma under direct current. Bioelectromagnetics 39, 460–475 (2018).

Goris, N. et al. Efficacy of direct current generated by multiple-electrode arrays on F3II mammary carcinoma: experiment and mathematical modeling. Journal Translational Medicine 18, 1–17 (2020).

Molski, M. & Konarski, J. Tumor growth in the space-time with temporal fractal dimension. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 36, 811–818 (2008).

Waliszewski, P. Complexity, diversity, homogeneity and topology measures re-define biological tumor aggressiveness as a function of intercellular connectivity. J Biomed Res Environ Sci. 15, 1290–1307 (2023).

Waliszewski, P. Complementarity, Complexity and the Fokker–Planck Equation; from the Microscale Quantum Stochastic Events to Fractal Dynamics of Cancer, 19–54 (Springer International Publishing, 2022).

Szasz, A. Time-fractal modulation-possible modulation effects in human therapy. Open journal Biophysics 12, 38–87 (2021).

Megyesfalvi, Z. et al. Clinical insights into small cell lung cancer: Tumor heterogeneity, diagnosis, therapy, and future directions. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 73, 620–652 (2023).

Helisaz, H., Belanger, E., Black, P., Bacca, M. & Chiao, M. Quantifying the impact of cancer on the viscoelastic properties of the prostate gland using a quasi-linear viscoelastic model. Acta Biomaterialia 173, 184–198 (2024).

Castañeda, A. et al. Spatio temporal dynamics of direct current in treated anisotropic tumors. Math Compt Simul 203, 609–632 (2023).

Zimmermann, M., Box, C. & Eccles, S. A. Two-dimensional vs. three-dimensional in vitro tumor migration and invasion assays. In Target Identification and Validation in Drug Discovery, 227–252 (Springer, 2013).

Ayers, G. D. et al. Volume of preclinical xenograft tumors is more accurately assessed by ultrasound imaging than manual caliper measurements. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 29, 891–901 (2010).

Friberg, S. & Mattson, S. On the growth rates of human malignant tumors: implications for medical decision making. Journal of surgical oncology 65, 284–297 (1997).

Davies, P. C., Demetrius, L. & Tuszynski, J. A. Cancer as a dynamical phase transition. Theoretical Biology and Medical Modelling 8, 1–16 (2011).

Zhang, Q. & Austin, R. H. Physics of cancer: the impact of heterogeneity. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 3, 363–382 (2012).

Murphy, H., Jaafari, H. & Dobrovolny, H. M. Differences in predictions of ODE models of tumor growth: a cautionary example. BMC cancer 16, 1–10 (2016).

Patmanidis, S., Charalampidis, A. C., Kordonis, I., Mitsis, G. D. & Papavassilopoulos, G. P. Comparing methods for parameter estimation of the Gompertz tumor growth model. IFAC-PapersOnLine 50, 12203–12209 (2017).

Geng, C., Paganetti, H. & Grassberger, C. Prediction of treatment response for combined chemo-and radiation therapy for non-small cell lung cancer patients using a bio-mathematical model. Scientific reports 7, 1–12 (2017).

Benzekry, S. et al. Classical mathematical models for description and prediction of experimental tumor growth. PLoS computational biology 10, e1003800 (2014).

Koziol, J. A., Falls, T. J. & Schnitzer, J. E. Different ODE models of tumor growth can deliver similar results. BMC cancer 20, 1–10 (2020).

Moré, J. J. The Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm: implementation and theory. In Numerical analysis, 105–116 (Springer, 1978).

Lange, K. L., Little, R. J. & Taylor, J. M. Robust statistical modeling using the t distribution. Journal of the American Statistical Association 84, 881–896 (1989).

Dehning, J. et al. Inferring change points in the spread of COVID-19 reveals the effectiveness of interventions. Science 369 (2020).

Tjørve, K. M. & Tjørve, E. The use of Gompertz models in growth analyses, and new Gompertz-model approach: An addition to the unified-Richards family. PloS one 12, e0178691 (2017).

Agur, Z., Elishmereni, M. & Kheifetz, Y. Personalizing oncology treatments by predicting drug efficacy, side-effects, and improved therapy: mathematics, statistics, and their integration. WIREs Syst Biol Med 6, 239–253 (2014).

Davidian, M., Giltinan, David M. & D. M.,. Nonlinear models for repeated measurement data: An overview and update. Journal of Agricultural, Biological, and Environmental Statistics 8, 387–419 (2003).

Motulsky, H. & Christopoulos, A. Fitting models to biological data using linear and nonlinear regression: a practical guide to curve fitting (Oxford University Press, 2004).

Neath, A. A. & Cavanaugh, J. E. The Bayesian information criterion: background, derivation, and applications. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics 4, 199–203 (2012).

Spiegelhalter, D. J., Best, N. G., Carlin, B. P. & Van der Linde, A. The deviance information criterion: 12 years on. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 76, 485–493 (2014).

Vrieze, S. I. Model selection and psychological theory: a discussion of the differences between the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). Psychological methods 17, 228 (2012).

Pooley, C. & Marion, G. Bayesian model evidence as a practical alternative to deviance information criterion. Royal Society open science 5, 171519 (2018).

De Santis, F. & Spezzaferri, F. Alternative Bayes factors for model selection. Canadian Journal of Statistics 25, 503–515 (1997).

Conigliani, C. & O’hagan, A. Sensitivity of the fractional Bayes factor to prior distributions. Canadian Journal of Statistics 28, 343–352 (2000).

O’Hagan, A. Fractional Bayes factors for model comparison. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 57, 99–118 (1995).

Lartillot, N. & Philippe, H. Computing Bayes factors using thermodynamic integration. Systematic biology 55, 195–207 (2006).

Haario, H., Laine, M., Mira, A. & Saksman, E. Dram: efficient adaptive MCMC. Statistics and computing 16, 339–354 (2006).

Sahin, K. H. & Ciric, A. R. A dual temperature simulated annealing approach for solving bilevel programming problems. Computers & chemical engineering 23, 11–25 (1998).

Raftery, A. E. Bayes factors and bic: Comment on “a critique of the bayesian information criterion for model selection’’. Sociological Methods & Research 27, 411–427 (1999).

Berger, J. O. & Mortera, J. Default Bayes factors for nonnested hypothesis testing. Journal of the american statistical association 94, 542–554 (1999).

Berger, V. W. & Zhou, Y. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test: Overview (Statistics reference online, Wiley statsref, 2014).

Van Rossum, G. & Drake, F. L. Python 3 Reference Manual (CreateSpace, Scotts Valley, CA, 2009).

Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0. Nature Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Miles, P. R. pymcmcstat: A python package for bayesian inference using delayed rejection adaptive metropolis. Journal of Open Source Software 4, 1417 (2019).

Cabrales, L. et al. Electrochemical treatment of mouse Ehrlich tumor with direct electric current. Bioelectromagnetics 22, 316–322 (2001).

Jarosz, A. F. & Wiley, J. What are the odds? a practical guide to computing and reporting Bayes factors. The Journal of Problem Solving 7, 2 (2014).

Skipper, H. E. Kinetics of mammary tumor cell growth and implications for therapy. Cancer 28, 1479–1499 (1971).

Grassberger, C. et al. Patient-specific tumor growth trajectories determine persistent and resistant cancer cell populations during treatment with targeted therapies. Cancer research 79, 3776–3788 (2019).

Friberg, S. On the growth rates of human malignant tumors: implications for medical decision making. Nowotwory. Journal of Oncology 55, 1–1 (2005).

Uzosike, A. C. et al. Growth kinetics of small renal masses on active surveillance: variability and results from the DISSRM registry. The Journal of urology 199, 641–648 (2018).

McIntosh, A. G. et al. Active surveillance for localized renal masses: tumor growth, delayed intervention rates, and> 5-yr clinical outcomes. European urology 74, 157–164 (2018).

Gerlee, P. The model muddle: in search of tumor growth laws. Cancer research 73, 2407–2411 (2013).

Zhang, C., Jiang, X., Guo, S. & Li, Q. Mathematical modeling of tumor growth in mouse models. Cancer Research 79, 4613–4613 (2019).

Held, L. & Sabanés Bové, D. Likelihood and Bayesian Inference: With Applications in Biology and Medicine. Statistics for Biology and Health (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2020), edition2nd edn.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the valuable suggestions of the three anonymous reviewers, responsible editor of the manuscript, and editor-in-chief. All comments contributed to the significant improvement of this manuscript. This study was financially supported by project ERASMUS+KA107 2020-1-ES01-KA107-081036 and grant PID2022-141385NB-I00 from Agencia estatal de investigación, Spain.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors E.R., L.B. and J.M. contributed equally to this work, doing the research and writing the manuscript. L.R. , S.S. and A.R.S.C. reviewed the manuscript

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ramirez-Torres, E.E., Castañeda, A.R.S., Rández, L. et al. Proper likelihood functions for parameter estimation in S-shaped models of unperturbed tumor growth. Sci Rep 15, 6598 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91146-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91146-1