Abstract

Microplastics (MPs), plastic particles with a diameter of < 5 mm, are intentionally produced or formed by the breakdown of a variety of larger plastics. Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) is a common source of MPs and PET-MPs are prevalent in the environment. Owing to their persistence, PET-MPs can enter ecosystems, air, and food sources, posing significant health risks. This study aimed to investigate the toxicological effects and in vivo accumulation of PET-MPs smaller than 10 µm. To track their biodistribution, fluorescently labeled PET-MPs were prepared. Particle size and morphology were confirmed using physical and chemical characterization. Following the oral administration of PET-MPs in ICR (CD-1®) outbred mice, accumulation occurred predominantly in lungs, as confirmed by IVIS spectrum CT analysis and in vivo and ex vivo imaging. Toxicity assays revealed the development of granulomatous inflammation in the lungs at medium and high doses, indicating a concentration-dependent response. The recorded no-observed-adverse-effect levels were 1.75 mg/kg for males and 7 mg/kg for females. This study highlights the potential of PET-MPs to induce persistent inflammation in respiratory tissues and reveals the need for further research to support the regulatory standards and long-term health effects of MP exposure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microplastics (MPs), plastic pieces of less than 5 mm in size, are produced by intentional miniaturization or the decomposition of larger plastic waste1,2,3,4,5. MPs can be classified into primary MPs, which are added to various industrial products, including abrasives, cosmetics, and cleaners and secondary MPs, which arise from the decomposition of plastics in nature, transforming them into smaller particles6,7. Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) is one of the most common MPs in the environment. It is used widely in consumer goods and packaging materials, including clothing fibers, packaging materials, and beverage bottles8,9. After their introduction to the environment, PET-MPs become spread throughout the ecosystem; as they are hard to decompose, they persist and accumulate in the environment, affecting humans and other living organisms10,11. Recently, concern regarding MPs has increased because of their abundance throughout the ecosystem and the discovery of possible exposure routes via the air, food, and potable water10. MPs in the air are especially likely to be inhaled via the respiratory tract, increasing the likelihood of their entry into human body upon food intake11,12,13. Human exposure via these routes occurs daily, increasing the likelihood of MPs entering the body and accumulating. Thus, it is imperative to understand the deleterious health impacts of these MPs, as particles of ≤ 10 µm in size can permeate the biological barriers of the body and penetrate deep into tissues14,15,16. Several recent studies have reported that MPs do not decompose rapidly and are not excreted in vivo17,18. The potential for MPs to exert deleterious effects on human health, especially upon long-term exposure, is reported, along with their accumulation in several organs, including the gastrointestinal tract, liver, lungs, and brain19,20,21,22. Owing to the small size and chemical stability of MPs, they may not be excreted from the body and may therefore accumulate, which may cause inflammatory reactions and cellular stress23,24. Despite their small size, MPs have a large surface area, facilitating their accumulation in human tissue, and their physical properties trigger immune responses; the inflammatory response is dependent on their surface characteristics and size25,26,27. Although the environmental impact of MPs is well not studied; information on their biological distribution, toxicity in mammalian systems, and organ residence. In particular, there are few studies on the effect of residence time in the human body on the toxicity of MPs, the pathways that leads to their accumulation in specific organs, and the toxic reactions occurring in these organs. Previous studies highlight the potential of small MPs (≤ 10 µm) to bypass biological barriers and accumulate in organs, leading to potential adverse effects. However, detailed investigations into the biodistribution and toxicity of PET-MPs remain limited. While some studies have explored the accumulation of microplastics in specific tissues, there is still insufficient information on the long-term fate and impact of PET-MPs within biological systems.

To address this gap, the present study investigates the biodistribution and toxicological effects of PET-MPs following oral administration in a murine model. We hypothesize that PET-MPs preferentially accumulate in the lungs and elicit dose-dependent inflammatory responses. This hypothesis is based on evidence suggesting that MPs of ≤ 10 µm in size have increased potential for deep tissue penetration and prolonged retention within biological compartments. To test this, we systematically evaluate organ-specific accumulation and histopathological changes associated with repeated exposure to PET-MPs. This study aims to provide a comprehensive assessment of PET-MP biodistribution and toxicity, contributing to a better understanding of their potential health risks.

Methods

Manufacture of PET-MPs

PET beads (Two H Chem Ltd., Goesan-gun, Korea) were frozen at − 78 °C in dry ice and then ground to a powder using a blade-type high-pressure homogenizer for 4–5 h. The powder was dispersed in ethanol, filtered through 5 µm and 15 µm mesh filters, washed 4–5 times with distilled water, and dried at 50 °C for 48 h. Finally, PET-MPs with a size of 10 µm or less were prepared.

Characterization of PET-MPs

Physical and chemical characterization was performed to verify that the manufactured plastic particles met the definition of PET-MPs. For physical characterization, particles were dispersed in ethanol (99.5%) and sonicated for 5 min to prevent aggregation before analysis, ensuring accurate size measurements, and then the average and distribution of particle sizes were measured using dynamic light scattering (DLS), whereas the actual shape and size was confirmed through scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and confocal microscopy (CM). Chemical characterization was performed using Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) and Raman spectroscopy. The morphology of microplastics was explored using a 20 × objective lens (Nikon LU Plan Flour 20 × /0.45), and Raman spectra were collected in the range of 160–3000 cm−1 using a grid with 300 lines/mm and a slit width of 50 µm with 10 scans of accumulation and 1 s of acquisition time. The MP spectrum was measured using a Peltier cooled charge-coupled element detector over a 16-bit dynamic range. For each scan, to obtain sufficient signals to conduct a library search, the accumulation number and acquisition time was adjusted. Prior to obtaining a spectrum and using silicon at a line of 520.7 cm−1, the spectrometer was calibrated. To enhance the spectral quality (Labspec 6 software, Horiba Scientific) and through vector normalization and polynomial baseline correction, the raw Raman spectra underwent noise reduction. The Raman spectra were compared with those of the spectral library using KnowItAll software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and SLOPP library of MPs. Similarities obtained above the Hit Quality Index of 80 were considered satisfactory.

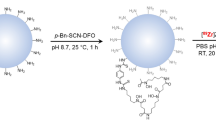

Fluorescence labeling of polypropylene microplastics

Using the combined swelling-diffusion methos for biodistribution analysis, PET-MPs were first fluorescently labeled28. PET-MPs (15 g) were added to distilled water (DW) (150 mL) and anhydrous alcohol (99.9%) (150 mL) and stirred for 10 min. Then, 0.5 mL of a Cy5.5-COOH solution (50 mg/mL in DMSO) (Lumiprobe) was added to a suspension of PET-MPs, and stirred at 60°C for 24 h. PET-MPs labeled with Cy5.5-COOH (Cy-PET-MPs) were vacuum-filtered through 2–3 µm filter paper to remove the unlabeled Cy5.5-COOH from the reaction mixture and then washed with ethyl alcohol and DW. Finally, the Cy-PET-MPs were dried at 40°C in the dark. The intensity and properties of the thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and FT-IR spectra of Cy-PET-MPs were recorded.

Animals and ethical approval statement

Five-week-old ICR mice (114 males and 114 females) were obtained from KOATECH Inc. (Pyeongtaek, Korea). During the in-house experiment, the mice were kept in a standard non-contaminated facility within ventilated IVC cages in a controlled environment (22°C ± 1 °C for 10–15 h, relative humidity of 50% ± 10%, illumination intensity of 150–300 lx for 12 h/day). All experimental methodologies and mouse care were approved and in accordance with guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), the Preclinical Center of the KMEDI hub (approval code: KMEDI-23112701–00) and followed the ARRIVE guideline.

In vivo biodistribution study of Cy5.5-COOH-labeled PET-MPs

10 males and 10 females six-week-old quarantined and refined ICR mice were separated into a control group and a Cy-PET-MP treatment group. Before fluorescence imaging, hair was removed from the mice and the mice were fasted for 8 h to avoid autofluorescence. Cy-PET-MPs dispersed in corn oil were orally administered to mice for 1 week at 2000 mg/kg. Using an IVIS Spectrum CT (Perkin Elmer, US), fluorescent images were acquired at emission and excitation wavelengths of 720 nm and 675 nm, respectively. During one week, in vivo images were acquired under 2.5% isoflurane anesthesia daily after 24h of administration and saline perfusion was performed through the left ventricle of the mouse before sacrifice, and organs were extracted for acquiring of ex vivo imaging after last imaging of in vivo.

Single-dose toxicity of PET-MPs

To investigate the toxic reactions induced by PET-MPs and confirm the approximate lethal dose (ALD), a single-dose oral administration toxicity assay was conducted. Six-week-old ICR mice (12 male or female) that were refined and completed their quarantine were separated into four major groups: a control group, a low-dose group (500 mg/kg), a medium-dose group (1000 mg/kg), and a high-dose group (2000 mg/kg). The control group was administered only corn oil; the other groups were administered a single oral dose of PET-MPs suspended in corn oil at a dosage 10 mL/kg. During a 2-week observation period, clinical signs, morbidity, and body weight were observed once per a day, twice per day, and once per week, respectively. Following the observation period, all treated mice were euthanized using carbon dioxide anesthesia, exsanguinated throughout the abdominal aorta, and subjected to necropsy and gross postmortem examinations. All experimental conditions were set in accordance with OECD Guideline No. 423.

4-week repeate-dose toxicity study of PET-MPs

To evaluate the toxicity and establish the no-observed-adverse-effect-level (NOAEL) of PET-MPs, a 4-week oral toxicity assay was conducted. Six-week-old ICR mice (40 male and 40 female) that were refined and completed quarantine, were allocated to one four groups; a control group, a low-dose group (1.75 mg/kg), a medium-dose group (7 mg/kg), and a high-dose group (28 mg/kg). The control group was orally administered PET-MPs daily for 4 weeks once per day, whereas the other three groups were orally administered 10 mL/kg dosage of PET-MPs suspended in corn oil. During the four-week observation period, clinical signs and morbidity were observed once per day and twice per day, respectively. Food and water consumption and body weight were measured once per week. After 4-week observation period, blood was collected via the abdominal aorta after the mice were exposed to isoflurane anesthesia at the end of the observation period. To perform hematological and hematochemical analyses about white blood cells, red blood cells, hemoglobin, mean corpuscular volume, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, platelet, differential count of white blood cell, reticulocyte, sodium, potassium, chloride, total protein, albumin, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, glucose, total bilirubin, phosphate, calcium, total cholesterol, triglyceride, alkaline phosphatase, alanine transaminase, aspartate aminotransferase, a blood cell analyzer (ADVIA 2120i, SIEMENS, Germany) and a serum biochemistry analyzer (TBA 120-FR; Toshiba, JP) were used, respectively. Complete gross postmortem examinations were conducted on all mice and their tissues, and the following organs were harvested: adrenal gland, brain, cecum, colon, duodenum, epididymis, esophagus, heart, ileum, jejunum, kidney, liver, lungs, ovary, pancreas, parathyroid gland, pituitary gland, rectum, spinal cord, spleen, stomach, testis, thymus, thyroid gland, trachea, and uterus. The brain, spleen, heart, kidney, lover, testis, epididymis, and ovary were weighed. All extracted organs were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin. For histopathological examination, a tissue processor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Runcorn, UK) was used to extract the tissues from the fixed samples. The tissue blocks embedded in formalin were cut into small pieces (4 µm thickness), mounted individually onto glass slides, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin using an autostainer (Dako Coverstainer; Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). One slide per organs was prepared for each animal, and whole field of the slide was evaluated in a blinded manner.

The doses in this study were selected based on high-end estimates of human microplastic exposure from food and water sources. Previous study estimated human dietary exposure levels between 0.1 and 5 mg/kg/day, and the chosen doses (1.75 mg/kg, 7 mg/kg, and 28 mg/kg) reflect chronic ingestion scenarios18. A dose range-finding test confirmed lung inflammation at 28 mg/kg, which was set as the highest dose to ensure meaningful toxicological endpoints. This approach aligns with previous studies and enhances microplastic risk assessment frameworks.

Detection of PET-MPs in biological samples

To detect PET-MPs in biological samples, mice organs were subjected to a pretreatment process. The organ samples were pooled and homogenized in 1:20 (w/w) 10% aqueous KOH solution. After homogenization, pooled samples were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h with shaking at 250 rpm. The samples were then filtered through a stainless steel filter disc (47 mm diameter; 45 μm pore size) and subsequently through a silicon filter (1 cm × 1 cm, 1 µm pore size). PET-MPs on the silicon filter were detected using a Raman microscope, as described before. PET-MPs were scanned for in an area of 500 × 375 μm2 in both x and y directions using an automated Raman point-by-point mapping mode.

Statistical analysis

The data was expressed in the form of mean ± standard deviation (SD). The statistical significance between the treated and control groups was checked by applying Student’s t-test using the SAS program (version 9.4 SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Physical and chemical properties of PET-MPs

The manufactured particles were analyzed using DLS, CM, and SEM to determine if they met the definition of the MPs, size of less than 5 mm in fragmented shapes, similar to those produced in the natural environmental, mainly by weathering. DLS analysis revealed that the average particle size was 5.64 ± 1.27 µm (Fig. 1a) and CM confirmed that the amorphous particles size was 10 µm or less (Fig. 1b). SEM analysis revealed the surface of the particles was irregular and fragmented particles (Fig. 1c). The physical properties of the manufactured particles were compliant with the definition of MPs. FT-IR and Raman spectroscopy analyses confirmed that the prepared MPs had the same chemical properties as raw PET plastics, as the same peaks were observed as in the reference PET spectrum. For FT-IR analysis, the characteristic peaks of PET were observed at 1715 cm⁻1 (C = O stretching of ester groups) and 1240 cm⁻1 (C–O stretching of ester groups), as shown in Fig. 2a. For Raman spectroscopy, the characteristic peaks were observed at 1610 cm⁻1 (aromatic ring stretching) and 860 cm⁻1 (C–C stretching in the aromatic ring), as shown in Fig. 2c. These peaks align well with the expected properties of PET, confirming the chemical composition of the manufactured MPs. (Fig. 2a–d). These physicochemical analyses results confirmed that these manufactured PET-MPs are an appropriate mimic of PET-MPs obtained in the environmental.

Characterization of the physical properties of PET-MPs. Images showing the size and morphology of PET-MPs obtained using dynamic light scattering (DLS), confocal microscopy (CM), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). (a) The average particle diameter of the 96,237 PET-MPs was calculated as 5.64 ± 1.27 µm. (b, c) The actual size was less than 10 µm and the morphology of the surface was irregular and fragmented. Scale bars: 20 µm (black) and 1 µm (white).

Stability and properties of the Cy5.5-COOH-labeled PET-MPs

The chemical characteristics of the manufactured PET-MPs were compared before and after labeling with Cy5.5-COOH and the spectral intensity was analyzed. The in vitro IVIS Spectrum CT image contained clear and strong signals from the Cy-PET-MPs (Fig. 3a). Such a strong intensity with 95% of the efficiency in the IVIS images (almost ~ 1010/50 mg) enabled the Cy-PET-MPs to be applied to an in vivo biodistribution study. From the FT-IR spectra and TGA, the chemical characteristics of PET-MPs before and after labeling with Cy5.5-COOH were not noticeably changed by labeling (Fig. 3b–e).

Changes in intensity and property of Cy5.5-COOH labeled-PET-MPs. Images (a) show the fluorescence intensity and properties of PET-MPs before (b, d) and after (c, e) labeling with Cy5.5-COOH, as analyzed by FT-IR and TGA; these were used to track the distribution and stability of MPs in the biological environment.

Biodistribution of the Cy5.5-COOH-labeled PET-MPs

In the IVIS images obtained after the administration of Cy-PET-MP during 1 week, compared with the control group, the Cy-PET-MPs remained in the stomach for 24 h after each administration (Fig. 4a). After 1 week, signals were detected ex vivo imaging of the lungs and stomach (Fig. 4b). These results indicated that the synthesized Cy-PET-MPs remained partially in the stomach following administration and that the signal not detected in vivo corresponded to the ex vivo signal detected in the lungs.

Biodistribution of Cy-PET-MPs in IVIS Spectrum CT images. (a) Compared to control group, Cy-PET administration group showed the signal in location of the stomach in vivo after each administration during one week. (b) After one week, the signals were detected in lungs and stomach of ex vivo images. (c) Quantitative analysis of the ex vivo images.

Single-dose and four-week repeat-dose toxicity

In the single-dose toxicity assay, no changes were observed related to administration of PET-MPs for mortality, body weight change, clinical symptoms, and necropsy. The ALD of PET-MPs was confirmed to be more than 2000 mg/kg.

Similarly, in the four-week repeat-dose toxicity assay, no changes related to the administration of PET-MPs were observed for mortality, body weight change, clinical symptoms, food and water consumption, necropsy, and clinical pathology. However, histopathological examination revealed granulomatous inflammation that was not present in normal lung structure (Fig. 5a,b). Moreover, mononuclear cells and a few lymphocytes were infiltrated into the terminal bronchioles and alveolar space (Fig. 5c). By adjusting the microscope condenser, the same part could be viewed at different focal points. Transparent particles of less than 10 μm were observed in the alveolar and terminal bronchioles and inflammatory cells that had infiltrated around the particles were observed (red arrow, Fig. 5d). These findings were recorded males of the medium-dose group and males and females of the high-dose group in males and females. Accordingly, the NOAEL was established to be 1.75 mg/kg in males and 7 mg/kg in females. The manufactured particles were generally not observed in the lungs, but were presumed to be PET-MPs based on their shape and size. These results suggest that orally administered PET-MPs may induce inflammation in the lungs.

Histopathological examinations of the mice lungs in the four-week repeat-dose toxicity assay. Microscopy examinations of mouse lungs after 4 weeks of repeated exposure to PET-MPs. (a) Normal lung tissue structure from the control group under low magnification, showing intact alveolar spaces and terminal bronchioles without any signs of inflammation or cellular infiltration. (b) High magnification of normal lung tissue from the control group, highlighting well-organized alveolar spaces and the absence of granulomatous inflammation or particle infiltration. (c) Lung tissue from the PET-MP-treated showing granulomatous inflammation with infiltration of mononuclear cells and lymphocytes in the terminal bronchioles and alveolar spaces. (d) Granulomatous region under higher magnification showing mononuclear cells and lymphocytes clustering around the terminal bronchioles and alveolar spaces and (e) particles presumed to be PET-MPs were observed when the condenser was adjusted. Scale bar: 200 µm (black) and 50 µm (red).

PET-MPs in the lungs

Analysis of the pretreated excised mouse organs using Raman spectroscopy revealed that they were detected in the lungs, as the same peaks were present in their spectra and the reference spectra (Fig. 6a,b). These results supported those of the ex vivo biodistribution assay, which found Cy-PET-MPs in the lungs, and provided supporting evidence for the toxicity assay results, which found that PET-MPs induced granulomatous inflammation in the lungs.

Discussion

The results of our study show that PET-MPs accumulate in specific organs over prolonged periods, mainly within the respiratory systems, and that this occurs because of their small size and chemical stability, and may result in localized inflammatory reactions. In this study, after oral administration of PET-MPs and Cy-PET-MPs to ICR mice, results of the Raman spectroscopy and IVIS spectrum CT provided clear evidence of the retention of PET-MPs, primarily in lungs, indicating that these MPs are not easily cleared from the body and can persist in tissues29,30,31. In vivo imaging may miss weaker signals due to tissue scattering and background noise, while ex vivo imaging provides higher sensitivity. MPs are more concentrated in the stomach, showing stronger signals in vivo, whereas lower lung concentrations are clearer ex vivo. Together, these methods offer complementary insights into Cy-PET-MP biodistribution. The observed distribution aligns with a previous study34, in which the ingested MPs can translocate to other organs of the body and may, depending on their size and surface properties, reach the respiratory tract, raising the possibility that pulmonary inflammation may occur after chronic exposure32. Notably, several studies have documented similar findings of microplastic accumulation in various animal models, thus reinforcing the concept that when MPs are small enough to penetrate the biological barriers, they can migrate from the gastrointestinal tract to other organ systems. Furthermore, the accumulation of MPs is supported by evidence that they likely enter systemic circulation, ultimately leading to widespread distribution and a significant toxicological impact.

Recent studies provide additional evidence supporting these observations. Latest study demonstrated that aged microplastics exacerbate bioenergetic imbalances and oxidative stress, suggesting that chronic exposure to fragmented plastics like PET-MPs could intensify their toxic effects in vivo33. Similarly, it has been reported the genotoxic and neurotoxic potential of nanoplastics, underscoring the broader systemic risks associated with prolonged exposure to MPs34. In particular, the potential for microplastics to affect other organs, such as the pancreas, has been highlighted, who observed transcriptomic changes associated with type 1 diabetes following PET-MP exposure35. These findings align with our observations and emphasize the need for regulatory standards to mitigate such risks36.

In addition, granulomatous inflammation in the lungs was observed, as characterized by the accumulation of mononuclear cells and presence of minor lymphocytes in repeat-dose assays. Thus, PET-MPs are likely to induce an immune response. A clear immune response was observed in higher dose groups, suggesting a dose-dependent impact and underscoring that even low chronic exposures may induce long-term inflammatory responses in respiratory tissues. Similarly, several studies revealed that exposure to MPs can activate different immune pathways, which lead to persistent inflammation, especially in sensitive lung tissues37,38. Many studies have reported that the size and surface characteristics of MPs may play a critical role in their interaction with immune cells, leading to chronic inflammatory responses and their associated health issues, including respiratory infections and reduced lung function39. In this study, the observed inflammatory responses were consistent with findings from previous investigations that have linked microplastic retention in the lungs to severe respiratory diseases, thus emphasizing the necessity for a deeper understanding of such interactions40,41.

An additional finding of this study is the potential role of microplastic surface characteristics in triggering immune responses. The surface properties of PET-MPs can alter their interactions with various cellular structures, particularly within sensitive tissues such as the lungs and the gastrointestinal tract. The high surface-to-volume ratio and rough surface of MPs may facilitate their interactions with immune cells, leading to localized inflammation and prolonged immune activation42. Smaller MPs were shown to penetrate deeply into tissues and evade normal clearance mechanisms, thus increasing the risk of chronic inflammatory conditions43. This phenomenon is particularly concerning for MPs smaller than 10 µm, which can accumulate in vulnerable tissues and evade normal physiological clearance mechanisms because of their size, enhancing their potential for a long-term impact on health32.

These findings of the study emphasize that PET-MPs can accumulate in specific body organs and trigger chronic inflammatory responses. The current results underscore the importance of future studies aimed at understanding the mechanisms by which PET-MPs may accumulate and persist in the body, in addition to their cumulative effects on health. Such studies are necessary to develop evidence-based guidelines for microplastic exposure and establish regulatory standards that will safeguard public health from the potential long-term impacts of MP pollution. Further studies on the interaction between MPs and biological systems are imperative for establishing safety thresholds and mitigating the risks associated with their presence in the environment, particularly as awareness of MP pollution continues to rise.

While this study provides robust evidence of PET-MP retention in the lungs and their potential to induce granulomatous inflammation, certain limitations must be acknowledged. One key limitation is the lack of quantitative data on the magnitude of observed inflammatory responses, such as the extent of granulomatous inflammation or the proportion of immune cell infiltration across treatment groups. Although the observed dose-dependent immune responses strongly suggest an association between PET-MPs and chronic inflammation, future studies should incorporate quantitative approaches, such as morphometry or inflammatory scoring, to better characterize the extent and severity of these changes.

Additionally, while the findings of PET-MP retention primarily in the lungs align with previous research, this study did not directly assess systemic translocation beyond the respiratory system. Speculative connections to broader systemic effects, such as impacts on the circulatory system, should be viewed as potential future research directions rather than definitive conclusions. Future studies should investigate whether PET-MPs can translocate to other organs or systems and assess their impacts on systemic health using advanced imaging and tracking techniques.

Another limitation is the absence of complementary methodologies to confirm the chemical identity of retained particles. While Raman spectroscopy provided valuable insights, the inclusion of additional techniques such as immunohistochemistry or co-localization analyses with inflammatory markers could provide stronger evidence for the association between PET-MPs and observed tissue responses. These techniques could also help confirm whether the observed inflammatory cells are directly interacting with the retained particles.

Finally, while this study emphasizes the chronic inflammatory effects of PET-MPs in the lungs, future research should explore their interactions with other organ systems and their potential to cause systemic inflammation or metabolic disturbances. Long-term studies investigating the cumulative effects of PET-MP exposure at environmentally relevant doses will be critical for establishing safety thresholds and regulatory standards.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that PET-MPs can persist in lung tissues and induce dose-dependent chronic inflammatory responses, including granulomatous inflammation. PET-MPs smaller than 10 µm were shown to evade normal clearance mechanisms, highlighting their potential to accumulate in sensitive tissues and pose significant risks to respiratory health.

These findings emphasize the need for further research to explore the systemic impacts of microplastic exposure and validate these observations using advanced methodologies. Establishing evidence-based guidelines and regulatory standards will be critical to mitigating the health risks associated with microplastic pollution.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Browne, M. A. Sources and pathways of microplastics to habitats. Marine anthropogenic litter, 229–244 (2015).

Coyle, R., Hardiman, G. & O’Driscoll, K. Microplastics in the marine environment: A review of their sources, distribution processes, uptake and exchange in ecosystems. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2, 100010 (2020).

Dris, R., Gasperi, J. & Tassin, B. Sources and fate of microplastics in urban areas: a focus on Paris megacity. Freshwater microplastics: emerging environmental contaminants? 69–83 (2018).

Eerkes-Medrano, D., Thompson, R. C. & Aldridge, D. C. Microplastics in freshwater systems: a review of the emerging threats, identification of knowledge gaps and prioritisation of research needs. Water Res. 75, 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2015.02.012 (2015).

Thompson, R. C. Microplastics in the marine environment: Sources, consequences and solutions. Marine anthropogenic litter, 185–200 (2015).

Lee, H.-S. & Kim, Y.-J. Estimation of microplastics emission potential in South Korea-For primary source. Sea: J. Korean Soc. Oceanogr. 22, 135–149 (2017).

Yano, K. et al. A comprehensive review of microplastics: Sources, pathways, and implications. J. Wetl. Res. 22, 153–160 (2020).

Hidalgo-Ruz, V., Gutow, L., Thompson, R. C. & Thiel, M. Microplastics in the marine environment: A review of the methods used for identification and quantification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 3060–3075. https://doi.org/10.1021/es2031505 (2012).

Xu, S., Ma, J., Ji, R., Pan, K. & Miao, A. J. Microplastics in aquatic environments: Occurrence, accumulation, and biological effects. Sci. Total Environ. 703, 134699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134699 (2020).

Schwabl, P. et al. Detection of various microplastics in human stool: A prospective case series. Ann. Intern. Med. 171, 453–457. https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-0618 (2019).

Habibi, N., Uddin, S., Fowler, S. W. & Behbehani, M. Microplastics in the atmosphere: A review. J. Environ. Expo. Assess. https://doi.org/10.20517/jeea.2021.07 (2022).

Prata, J. C. Airborne microplastics: Consequences to human health?. Environ. Pollut. 234, 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.11.043 (2018).

Salvador Cesa, F., Turra, A. & Baruque-Ramos, J. Synthetic fibers as microplastics in the marine environment: A review from textile perspective with a focus on domestic washings. Sci. Total Environ. 598, 1116–1129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.04.172 (2017).

Amato-Lourenco, L. F. et al. Presence of airborne microplastics in human lung tissue. J. Hazard. Mater. 416, 126124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126124 (2021).

Jenner, L. C. et al. Detection of microplastics in human lung tissue using muFTIR spectroscopy. Sci. Total Environ. 831, 154907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154907 (2022).

Niari, M. H. et al. Characteristics and assessment of exposure to microplastics through inhalation in indoor air of hospitals. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 18, 1–10 (2024).

Deng, Y., Yan, Z., Zhu, Q. & Zhang, Y. Tissue accumulation of microplastics and toxic effects: widespread health risks of microplastics exposure. Microplastics in Terrestrial Environments: Emerging Contaminants and Major Challenges, 321–341 (2020).

Smith, M., Love, D. C., Rochman, C. M. & Neff, R. A. Microplastics in seafood and the implications for human health. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 5, 375–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-018-0206-z (2018).

Lu, L., Wan, Z., Luo, T., Fu, Z. & Jin, Y. Polystyrene microplastics induce gut microbiota dysbiosis and hepatic lipid metabolism disorder in mice. Sci. Total Environ. 631–632, 449–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.03.051 (2018).

Qiao, R. et al. Microplastics induce intestinal inflammation, oxidative stress, and disorders of metabolome and microbiome in zebrafish. Sci. Total Environ. 662, 246–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.245 (2019).

Shan, S., Zhang, Y., Zhao, H., Zeng, T. & Zhao, X. Polystyrene nanoplastics penetrate across the blood-brain barrier and induce activation of microglia in the brain of mice. Chemosphere 298, 134261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134261 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Polystyrene microplastics induce size-dependent multi-organ damage in mice: Insights into gut microbiota and fecal metabolites. J. Hazard. Mater. 461, 132503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.132503 (2024).

Aguilar-Guzmán, J. C. et al. Polyethylene terephthalate nanoparticles effect on RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. Microplast. Nanoplast. 2, 9 (2022).

da Silva Brito, W. A. et al. Sonicated polyethylene terephthalate nano- and micro-plastic-induced inflammation, oxidative stress, and autophagy in vitro. Chemosphere 355, 141813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.141813 (2024).

He, Y. et al. Cytotoxic effects of polystyrene nanoplastics with different surface functionalization on human HepG2 cells. Sci. Total Environ. 723, 138180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138180 (2020).

Jeon, S. et al. Surface charge-dependent cellular uptake of polystyrene nanoparticles. Nanomaterials (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8121028 (2018).

Varela, J. A., Bexiga, M. G., Aberg, C., Simpson, J. C. & Dawson, K. A. Quantifying size-dependent interactions between fluorescently labeled polystyrene nanoparticles and mammalian cells. J. Nanobiotechnol. 10, 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-3155-10-39 (2012).

Mali, G. et al. Effective synthesis and biological evaluation of functionalized 2,3-dihydrofuro[3,2-c]coumarins via an imidazole-catalyzed green multicomponent approach. ACS Omega 7, 36028–36036. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c05361 (2022).

Jo, J. et al. Immunodysregulatory potentials of polyethylene or polytetrafluorethylene microplastics to mice subacutely exposed via intragastric intubation. Toxicol. Res. 39, 419–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43188-023-00172-6 (2023).

Lee, S. et al. Toxicity study and quantitative evaluation of polyethylene microplastics in ICR mice. Polymers (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14030402 (2022).

Lu, T. et al. Potential effects of orally ingesting polyethylene terephthalate microplastics on the mouse heart. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 24, 291–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12012-024-09837-6 (2024).

Yang, Z. et al. Human microplastics exposure and potential health risks to target organs by different routes: A review. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 9, 468–485 (2023).

Cheng, W. et al. Aged fragmented-polypropylene microplastics induced ageing statues-dependent bioenergetic imbalance and reductive stress: In vivo and liver organoids-based in vitro study. Environ. Int. 191, 108949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2024.108949 (2024).

Casella, C. & Ballaz, S. J. Genotoxic and neurotoxic potential of intracellular nanoplastics: A review. J. Appl. Toxicol. 44, 1657–1678 (2024).

Mierzejewski, K. et al. Oral exposure to PET microplastics alters the pancreatic transcriptome-implications for the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.11.05.622142 (2024).

Casella, C., Vadivel, D. & Dondi, D. The current situation of the legislative gap on microplastics (MPs) as new pollutants for the environment. Water Air Soil Pollut. 235, 1–27 (2024).

Bishop, C. R. et al. Microplastics dysregulate innate immunity in the SARS-CoV-2 infected lung. Front. Immunol. 15, 1382655. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1382655 (2024).

Woo, J. H. et al. Polypropylene nanoplastic exposure leads to lung inflammation through p38-mediated NF-kappaB pathway due to mitochondrial damage. Part Fibre Toxicol. 20, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12989-022-00512-8 (2023).

Yang, W. et al. Impacts of microplastics on immunity. Front. Toxicol. 4, 956885 (2022).

Chen, Q. et al. An emerging role of microplastics in the etiology of lung ground glass nodules. Environ. Sci. Eur. 34, 25 (2022).

Lu, K. et al. Microplastics, potential threat to patients with lung diseases. Front. Toxicol. 4, 958414. https://doi.org/10.3389/ftox.2022.958414 (2022).

Cheng, Y., Yang, Y., Bai, L. & Cui, J. Microplastics: an often-overlooked issue in the transition from chronic inflammation to cancer. J. Transl. Med. 22, 959. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-024-05731-5 (2024).

Mahmud, F., Sarker, D. B., Jocelyn, J. A. & Sang, Q.-X.A. Molecular and cellular effects of microplastics and nanoplastics: Focus on inflammation and senescence. Cells 13, 1788 (2024).

Funding

This study was supported by the Korea Environment Industry & Technology Institute (KEITI) through Measurement and Risk assessment Program for Management of Microplastics Project, funded by the Korea Ministry of Environment (MOE) (grant No. 2020003120002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L.; animal study, D.K., H.-K.K; pathological analysis, S.L., D.K., M.S., S.-E.S, J.-H.C., Y.L., K.-K.K., E.J.; Raman analysis D.K., S.L.; writing—original draft, D.K.; supervision and writing—review, S.L.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), the Preclinical Center of the KMEDI hub, with an approval code of. KMEDI-23112701-00.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, D., Kim, D., Kim, HK. et al. Organ-specific accumulation and toxicity analysis of orally administered polyethylene terephthalate microplastics. Sci Rep 15, 6616 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91170-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91170-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Effects of microplastic on submerged nanofiltration for advanced drinking water treatment

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

FTIR based assessment of microplastic contamination in soil water and insect ecosystems reveals environmental and ecological risks

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Multi-dimensional View of Microplastic Toxicity: Environmental and Health impacts

Water, Air, & Soil Pollution (2025)