Abstract

We aimed to explore the association of hyperkalemia and short- and mid-term mortality in critically ill patients using the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC-IV) database. Adult patients who had been stayed in the intensive care unit (ICU) for at least 48 h and tested for serum potassium were included. Hyperkalemia was defined as serum potassium higher than 5.5 mmol/L. Exposures included the occurrence the timing of hyperkalemia and the numeric values of serum potassium. The outcomes included ICU mortality and 7 days and 30 days mortality after ICU admission. Survival curves were calculated according to Kaplan–Meier analysis. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of each exposure for the outcomes. Subgroup analyses after full adjustment were conducted. A total of 22,370 ICU patients were included in this study. The prevalence of hyperkalemia was 18.8%. Patients with and without hyperkalemia differed significantly in a number of baseline characteristics. The ICU mortality, 7 days mortality, and 30 days mortality rates in the overall population were 12.6%, 9.5%, and 19.1%, respectively. After full adjustment, the occurrence of hyperkalemia is closely associated with the ICU mortality (HR: 1.39; 95% CI: 1.22–1.58) and 30 days mortality (HR: 1.16; 95% CI: 1.03–1.31) of the ICU patients. The timing of hyperkalemia is also associated with the risk of mortalities. These associations remained unchanged in the multiple regression analysis after full adjustment for the demographic variables, clinical tests, and comorbidities. In conclusion, the occurrence and timing of hyperkalemia are closely associated with the ICU and 30 days mortalities of critically ill patients. Once hyperkalemia occurs, active interventions are needed to restore serum potassium levels, regardless of the numeric values, to normal as quickly as possible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hyperkalemia, defined as serum potassium level over 5.5 mmol/L, is a common electrolyte disorder, which can occur due to a variety of reasons that disrupt the body’s delicate potassium balance1. Most often, hyperkalemia results from impaired urinary potassium excretion due to declined renal function, either acute or chronic. Other reasons include excessive intake, tissue breakdown, medications, and hemolysis2,3,4. The dangers associated with hyperkalemia, if left untreated, are primarily related to its impact on the cardiovascular system and muscle function, including the potential for life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias2. Thus, hyperkalemia is a clinically significant issue that requires vigilant monitoring, especially in high-risk patients, and timely intervention to prevent serious complications.

The prevalence of hyperkalemia is high in hospitalized patients5. Elevated baseline potassium level within reference range is associated with worse clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients6. Substantial increase in healthcare costs associated with hyperkalemia events was observed in patients who had hyperkalemia compared to those who hadn’t7. Previous studies also reported an association between hyperkalemia and increased mortality in cardiac intensive care unit patients8 and patients with comorbidities such as heart failure, chronic kidney disease (CKD), or diabetes9. Hyperkalemia in association with acute kidney injury (AKI) was a strong predictor of in-hospital death10. However, there is still a lack of reports on the association between hyperkalemia and mortalities in critically ill patients.

Therefore, we set out to explore the association of hyperkalemia and short- and mid-term mortality in critically ill patients from multiple perspectives using the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care database. We sought to gain insight into the adverse effects of hyperkalemia in critically ill patients and enhance the awareness of healthcare professionals to this electrolyte disorder.

Materials and methods

Study population

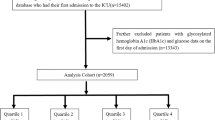

We used data from the latest Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC-IV-3.0) database to conducted this study11. MIMIC-IV is freely and publicly accessible electronic health record dataset which encompasses over 50,000 ICU admissions at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts, from 2008 to 201912 and contains information on demographics, vital signs, test results, and diagnoses categorized using the ninth and tenth revisions codes from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). Adult (≥ 18 years) ICU patients who had been stayed in ICU for at least 48 h and tested for serum potassium were included in this study. Only the first ICU admission (index ICU admission) was considered for patients with multiple ICU admissions. Patients with record of kidney replacement therapy (KRT) before the onset of AKI and those with death recorded before ICU admission were excluded. We also excluded patients with diagnosis of chronic kidney disease (stage 5), chronic kidney disease (stage 4, severe), and end state renal disease on discharge. Individual patient consent was not needed due to the anonymized nature of the information within this database.

Exposures of hyperkalemia

Hyperkalemia was defined as serum potassium level higher than 5.5 mmol/L1. In this study, we assessed exposures of hyperkalemia from three dimensions. The first dimension was the occurrence of hyperkalemia, including hyperkalemia defined as at least one episode of serum potassium over 5.5 mmol/L and the percentage of hyperkalemia out of the total potassium tests during the index admission. The second dimension was the level of hyperkalemia, defined as the values of potassium at the first occurrence of hyperkalemia and the maximal potassium level during the index admission. The third dimension was the timing of hyperkalemia, including the time from ICU admission to the first episode of hyperkalemia, the time from ICU admission to the maximal potassium level, the time from the first episode of hyperkalemia to the maximal potassium level, and whether the first episode of hyperkalemia was the maximal potassium level.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of this study was ICU mortality. The secondary outcomes included mortality within 7 days and 30 days after admission to the ICU, respectively. The time from ICU admission to death, expressed either in hours and days, was calculated by comparing the time of death to the time of ICU admission. Mortality information for discharged patients was acquired from the US Social Security Death Index.

Variable extractions

Data extracted from the MIMIC-IV database can be divided into the following four categories: (1) Demographic variables: age, sex, and race; (2) Comorbidities: hypertension, diabetes, heart failure, myocardial infarction, shock, and sepsis; (3) Clinical indices: vital signs upon ICU admission, length of stay in ICU, AKI and associated stages, KRT, time of ICU admission, and time of death; and (4) Laboratory variables: white blood cell count (WBC), hemoglobin (HGB), serum creatinine, blood urine nitrogen (BUN), sodium (Na), carbonate (CO2), and chloride (Cl).

Comorbidities were extracted from the diagnosis module in the database and diagnosed using the International Classification of Disease (ICD) code 9 or 10. The definition and staging of acute kidney injury (AKI) were based on changes in serum creatinine using the KDIGO criteria13. Vital signs recorded at admission included heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation (SpO2). Mean arterial pressure was calculated using (2*systemic blood pressure + diastolic blood pressure)/3. Laboratory variables were the first measurement after admission, except for potassium for which all tests during the index admission were recorded.

To access this database, Yunlin Feng had obtained the necessary certification (certification number: 45370361) and extracted the relevant variables. All information was extracted using PostgresSQL (version 13.7.2) and Navicat Premium (version 16) softwares via Structured Query Language (SQL).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR) based on normality testing results by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Categorical variables were reported as number and percentage. Statistical comparisons between groups were performed using Student’s t-test, ANOVA test, Wilcoxon rank sum test, and chi-square test as appropriate. Missing data were imputed using multiple imputation.

Survival curves for the three examined outcome were calculated according to Kaplan–Meier analysis and log-rank test was employed to evaluate the differences in the mortalities stratified by the occurrence of hyperkalemia. Univariate Cox proportional hazard regression model was applied to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) of each exposure for the risk of examined outcomes. Three multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression models were established to estimate the HR and 95% CI of hyperkalemia for the risk of the three outcomes after adjustment for: (1) demographic information (sex, age, and race) in Model 1; (2) the above demographic information and clinical variables (blood pressure, heart rate, creatinine, urine nitrogen, and hemoglobin) in Model 2; and (3) the above demographic and clinical variables and comorbidities (diabetes, sepsis, hypertension, heart failure, shock, and myocardial infarction) in Model 3. Subgroup analyses based on sex, age, diabetes, sepsis, AKI, and AKI stages were conducted to explore the specific effects of the occurrence and timing of hyperkalemia on the risk of the examined mortalities in the fully adjusted Model 3.

The statistical analysis was performed using R 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) with the R packages “survival” and “ggplot2”. A two-sided p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

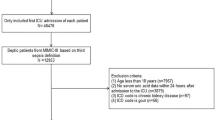

A total of 22,370 critically ill patients were included in this study (Fig. 1). The mean age of the whole population was 65.7 (SD: 16.9) years and 56.4% were men. 4,195 (4,195/22,370, 18.8%) patients developed hyperkalemia after ICU admission, among which about one half (2,221/4,195, 52.9%) only had one episode, while the other half (1,974/4,195, 47.1%) had recurrent hyperkalemia. The episodes of hyperkalemia during a single admission varied greatly from 1 to 27 times.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the overall populations and subgroups based on the presence of hyperkalemia are shown in Table 1. Patients with and without hyperkalemia differed significantly in a number of baseline characteristics. The prevalence of diabetes, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and shock was more common in patients with hyperkalemia, whereas hypertension was more commonly observed in patients without hyperkalemia. Vital signs including blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation did not differ between the two groups. The patients with hyperkalemia tended to stay longer in ICU (medians: 5.0 vs. 3.6 days), have longer length of stay in hospital (medians: 11.9 vs. 8.1 days), received more KRT (13.3% vs. 1.4%), and were more likely to be diagnosed with AKI (65.3% vs. 34.8%) and higher grades of AKI compared to those without hyperkalemia. The level of serum creatinine was significantly higher in patients with hyperkalemia in comparison to those without hyperkalemia (means: 1.8 vs. 1.1 mg/dL).

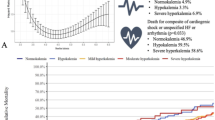

Outcomes and survival analysis

The ICU mortality, 7 days mortality, and 30 days mortality rates in the overall population were 12.6% (2,820/22,370), 9.5% (2,121/22,370), and 19.1% (4,275/22,370), respectively. Patients with hyperkalemia had significantly higher ICU morality rate (25.2% vs. 7.9%), 7 days mortality rate (15.3% vs. 8.1%), and 30 days mortality rate (31.6% vs. 16.2%) in comparison to those without hyperkalemia (Table 2). The Kaplan-Meier curves derived from survival analysis indicated patients with hyperkalemia had significantly higher risk for the ICU mortality, 7 days mortality, and 30 days mortality (Fig. 2).

Cox regression analysis results

Univariable regression analysis indicated the occurrence of hyperkalemia in terms of hyperkalemia itself and the percentage of hyperkalemia out of the total blood potassium tests was associated with higher risk of both short-term and mid-term mortalities (Table 3). The absolute value of potassium at the occurrence of hyperkalemia, neither at the first occurrence of hyperkalemia nor the maximal potassium level, was not associated with higher risk of the short-term and mid-term mortalities. The longer the time from admission to the onset of hyperkalemia, the lower the risk of mortality. Patients who had the maximal potassium level at the first occurrence of hyperkalemia had lower risk of mortality than those who had not. In addition, the increased duration from the first occurrence of hyperkalemia to the maximal potassium was associated with higher risk of mortality. These associations remained unchanged in the multiple regression analysis after full adjustment for the demographic variables, clinical tests, and comorbidities (Table 4; Figs. 3, 4 and 5). Subgroups analysis indicated none of the examined covariates including sex, age, diabetes, sepsis, AKI, and AKI stages impact the survival outcomes (sFigs. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5).

Discussion

The main findings of this study indicated that after full adjustment, the occurrence of hyperkalemia is closely associated with the ICU mortality (HR: 1.39; 95% CI: 1.22–1.58) and 30 days mortality (HR: 1.16; 95% CI: 1.03–1.31) of the critically ill patients. The values of potassium at the occurrence of hyperkalemia are not significantly associated with the mortalities. The timing of hyperkalemia is also associated with the risk of mortalities. The longer the time from admission to the onset of hyperkalemia or the shorter the duration from the first occurrence of hyperkalemia to the maximal potassium, the lower the risk of mortality. These associations remained unchanged in the multiple regression analysis after full adjustment for the demographic variables, clinical tests, and comorbidities.

The close association between hyperkalemia and higher risk of mortality is consistent with previous reports2,6,8,10 and has already been recognized by well accepted clinical scores14, among which APACHE II15 and SAPS II16 include serum potassium as one predictive variable to assess the risk of patients. After adjusting for multiple factors including demographic variables, clinical tests, and comorbidities, we have once again confirmed the increased short- and mid-term mortalities at the occurrence of hyperkalemia in a broader ICU patient population, rather than a specific ICU population and this correlation remained stable across various subgroups. Unexpectedly, our results suggested that the specific numerical values of the serum potassium upon the first occurrence of hyperkalemia were not significantly related to the mortalities, and the association between the occurrence of hyperkalemia and the outcomes was stronger than that between the numeric value of maximal potassium and the outcomes. The explanation to this finding might be that hyperkalemia draws close attention from medical professionals; thus, prompt interventions are undertaken regardless of the numerical value due to the well-known complications including life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias, muscle weakness and paralysis, neurological symptoms, and digestive issues.

An interesting finding of this study is that the timing of hyperkalemia and the speed at which serum potassium levels rise to their peak are both closely related to the risk of mortality, which has not been previously reported in the literature. We found that the longer the time from ICU admission to the first occurrence of hyperkalemia or the highest serum potassium value, the lower the risk of death. In other words, the earlier hyperkalemia occurs, which may reflect more severe disease or more complex life-threatening situations, the greater the risk of death. Furthermore, the longer the time from the first occurrence of hyperkalemia to the highest serum potassium value, the greater the risk of death, indicating that the risk of mortality increases with the time to reach peak potassium levels. Additionally, we found that patients who had the highest serum potassium values at their first episode of hyperkalemia had a lower risk of death, for which the underlying reason might be that these patients received more aggressive interventions due to their high serum potassium levels, leading to better outcomes.

This is the largest sample study so far on the correlation between hyperkalemia and the risk of mortality in a well-organized dataset. Our findings once again confirm the dangers of hyperkalemia and, for the first time, analysed the correlation between the timing of hyperkalemia and the risk of mortality. The findings suggest that we clinicians should pay attention to hyperkalemia and, once it occurs, actively manage it to restore serum potassium levels to normal as quickly as possible. There are some limitations to be noted. First, this is a retrospective study, which can only prove correlation, instead of causality. As is well known, hyperkalemia often coexists with a variety of critical illnesses, which already have a high risk of death, so hyperkalemia may merely reflect the severity of the condition. Second, there are many factors that affect the mortality of ICU patients and it is impossible to completely rule out every potentially confounding factor. This should be taken into account when interpreting the results.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicated that the occurrence and timing of hyperkalemia are both closely associated with the ICU mortality and 30 days mortality of critically ill patients. The earlier hyperkalemia occurs, or the longer the time from the first occurrence of hyperkalemia to peak potassium level, the greater the risk of death. These significant associations remained unchanged after full adjustment. We should pay attention to hyperkalemia and, once it occurs, actively manage it to restore serum potassium levels, regardless of the numeric values, to normal as quickly as possible.

Data availability

The data analyzed or generated during the study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Palmer, B. F. et al. Clinical management of hyperkalemia. Mayo Clin. Proc. 96(3), 744–762 (2021).

McLean, A., Nath, M. & Sawhney, S. Population epidemiology of hyperkalemia: Cardiac and kidney Long-term health outcomes. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 79(4), 527–538e1 (2022).

Robert, L. et al. Hospital-Acquired hyperkalemia events in older patients are mostly due to avoidable, multifactorial, adverse drug reactions. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 105(3), 754–760 (2019).

Usuda, D. et al. Crush syndrome: A review for prehospital providers and emergency clinicians. J. Transl Med. 21(1), 584 (2023).

Humphrey, T. et al. How common is hyperkalaemia? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and incidence of hyperkalaemia reported in observational studies. Clin. Kidney J. 15(4), 727–737 (2022).

Park, S. et al. Elevated baseline potassium level within reference range is associated with worse clinical outcomes in hospitalised patients. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 2402 (2017).

Kim, K. et al. Healthcare resource utilisation and cost associated with elevated potassium levels: A Danish population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 9(4), e026465 (2019).

Brueske, B. et al. Hyperkalemia is associated with increased mortality among unselected cardiac intensive care unit patients. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8(7), e011814 (2019).

Collins, A. J. et al. Association of serum potassium with All-Cause mortality in patients with and without heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and/or diabetes. Am. J. Nephrol. 46(3), 213–221 (2017).

Chothia, M. Y. et al. Outcomes of hospitalised patients with hyperkalaemia at a South African tertiary healthcare centre. EClinicalMedicine 50, 101536 (2022).

Johnson, A. et al. MIMIC-IV (version 3.0). PhysioNet https://doi.org/10.13026/hxp0-hg59 (2024).

Johnson, A. E. W. et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci. Data 10(1), 1 (2023).

Kellum, J. A., Lameire, N. & Group, K. A. G. W. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of acute kidney injury: A KDIGO summary (Part 1). Crit. Care 17(1), 204 (2013).

Keuning, B. E. et al. Mortality prediction models in the adult critically ill: A scoping review. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 64 (4), 424–442 (2020).

Knaus, W. A. et al. APACHE II: A severity of disease classification system. Crit. Care Med. 13(10), 818–829 (1985).

Le Gall, J. R., Lemeshow, S. & Saulnier, F. A new simplified acute physiology score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA 270(24), 2957–2963 (1993).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Prof. Martin Gallagher from UNSW, Australia for the assistance in the English writing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chuan Xu: software, data analysis and interpretation, writing-original draft preparation; Yong Luo: data analysis and interpretation, writing- reviewing and editing; Xiuling Chen: data analysis and interpretation, writing- reviewing and editing; Yunlin Feng: conceptualization, methodology, data curation and analysis, writing-reviewing and editing. All authors contributed to revise the manuscript critically to incorporate important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be submitted.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, C., Luo, Y., Chen, X. et al. Hyperkalemia is associated with short- and mid-term mortalities in critically ill patients in the MIMIC IV database. Sci Rep 15, 6539 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91194-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91194-7