Abstract

Previous studies have shown that patients with rosacea tend to have a higher risk of developing cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). However, the potential causal relationship between genetic susceptibility to rosacea and the risk of CVDs remains unclear. Based on summary statistics from publicly available genome-wide association studies (GWASs), we detected the genetic association between rosacea and CVDs by a bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis. The inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method was used as the primary analysis, while weighted median (WM) and MR-Egger were applied as complementary methods. For sensitivity analyses, we applied Cochran’s Q test, the intercept of MR-Egger, MR-Pleiotropy Residual Sum and Outlier (MR-PRESSO), funnel plot, and leave-one-out analysis. The MR analysis revealed that rosacea was associated with an elevated risk of hypertension (HTN) (OR = 1.0032, 95% CI [1.0001–1.0063], P = 0.04). However, no casual relationship was found between rosacea and risk of atrial fibrillation (AF) (OR = 1.0099, 95% CI [0.9823–1.0382], P = 0.49), coronary artery disease (CAD) (OR = 1.0138, 95% CI [0.9824–1.0462], P = 0.39), heart failure (HF) (OR = 0.9965, 95% CI [0.9671–1.0268], P = 0.82), ischemic stroke (IS) (OR = 0.9933, 95% CI [0.9545–1.0337], P = 0.74), or myocardial infarction (MI) (OR = 1.0001, 95% CI [0.9988–1.0013], P = 0.92). In the sensitivity analysis, significant heterogeneity was revealed in the MI subgroup according to the Cochran’s Q test. Other sensitivity analyses indicated the stability of our results. Reverse MR analysis showed no significant genetic effect of cardiovascular disease on rosacea risk. We are the first to use MR analysis to explore the casual relationship between rosacea and the risk of various CVDs, revealing an increased risk of HTN in patients with rosacea.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rosacea, a chronic inflammatory condition, predominantly affects individuals aged 20 to 50, particularly those with fair skin, with prevalence rates ranging from 0.09% to 22%1,2. Its characteristics include erythema, flushing, telangiectasia, papules, and pustules in the middle of the face. Although the exact pathogenesis of rosacea remains unclear, substantial evidence indicated that chronic inflammation, immune dysregulation, genetic factors, and neurovascular dysregulation are the main pathogenic factors3,4,5,6.

Previously, rosacea was considered a skin specific disease. However, an increasing number of researches suggested that rosacea has systemic effects, including on cardiovascular diseases (CVDs)6,7,8,9,10. It is known that chronic inflammation plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of various CVDs. In addition, some risk factors, such as smoking, psychological stress and diet, are common in the pathogenesis of rosacea and CVDs6,11,12. However, previous studies had the inevitable inherent shortcomings of observational studies, which can be affected by unmeasured confounders and cannot determine the causality between exposure and outcome .

Mendelian randomization (MR) is a method that employs genetic variants as instrumental variables (IVs) to investigate causal relationships13,14. Two-sample MR is a method used to perform MR using genetic data from two independent samples, typically one for the exposure and one for the outcome. This approach is advantageous over single-sample MR, where both exposure and outcome data are derived from the same sample. Single-sample MR is more susceptible to bias and confounding because it can be influenced by sample overlap or population stratification, which may lead to inflated or misleading results. On the other hand, two-sample MR helps to avoid these issues by using data from separate, independent samples, thus improving the robustness of the causal inference. By capitalizing on genetic variants randomly allocated at conception, MR mitigates confounding biases inherent in observational studies. Additionally, the predetermined nature of genetic makeup precludes the issue of reverse causality, as it is established prior to any later-life outcomes. Moreover, the reliance on genetic data, which are less susceptible to measurement errors than self-reported variables, further minimizes the risk of information bias. Despite its own constraints, such as pleiotropic effects where a single genetic variant influences multiple traits, MR can offer a more rigorous framework for causal inference than traditional observational studies.

In the present study, a bidirectional two-sample MR approach utilizing using data from Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) was employed to investigate the genetic causality between rosacea and CVD risk.

Methods

Study design

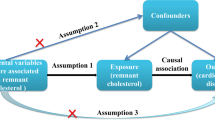

To investigate the causal association between rosacea and different CVDs, including atrial fibrillation (AF), heart failure (HF), ischemic stroke (IS), coronary artery disease (CAD), myocardial infarction (MI), and hypertension (HTN), using a bidirectional two-sample MR approach15. This study will operate under the following three main hypotheses: 1) IVs Relevance: Genetic instruments used in the analysis are robustly associated with the exposure variable, which in this case is rosacea. 2) IVs Independence: The selected genetic instruments are not associated with any confounders that may affect the relationship between the exposure (rosacea) and the outcomes (AF, CAD, HF, IS, MI and HTN). 3) IVs excludability: The genetic instruments affect the outcome variables only through the exposure, with no direct effects on the outcomes. An overview of the study design is shown in Fig. 1.

Ethics approval

All analyses of this study were based on the publicly available data, and ethical approval had been obtained in the original studies.

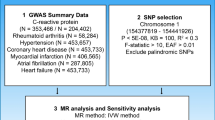

Data sources

The summary data for rosacea was sourced from FinnGen16 and encompassed 431,664 samples, comprising 2,455 cases and 429,209 controls. For the outcomes, we mainly focused on the association of rosacea with AF, CAD, HF, IS, MI and HTN. We selected the largest published GWAS summary statistic to date for the target outcomes among European population. The GWAS dataset for AF were included 60,620 cases and 970,216 controls17. Summary data for CAD was obtained from the UK Biobank and included 122,733 cases and 424,528 controls18. Summary statistics for HF consisted 47,309 cases and 930,014 controls19. Summary-level data for IS comprised 11,929 cases and 472,192 controls20. For MI, we used summary-level statistical data from the UK Biobank, which included 484,598 individuals21. The GWAS dataset for HTN were included 129,909 cases and 354,689 controls21. All populations represented in the GWAS were of European descent. The sources of datasets included in the MR are listed in Table 1.

Genetic instrumental variable selection

We screened single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) based on the following criteria: 1) We select genetic variants that reach a stringent level of statistical significance (P < 5 × 10–8) in the GWAS. This ensures that the genetic variant is strongly related to the exposure. 2) We ensure the selected SNPs are not in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with one another, and we set the threshold at r2 < 0.001 between any pair of SNPs22. 3) We compute F-statistics for each potential IV to evaluate its strength22. An F-statistic greater than 10 is considered a strong IV. 4) PhenoScanner V2: we use PhenoScanner V2 to scan for associations between the selected SNPs and a range of phenotypes. This can give an idea if the SNP is associated with any confounders23. 5) We eliminated SNPs with incompatible alleles or palindromic SNPs exhibiting intermediate allele frequencies.

Statistical analysis

The study employs three MR methods: Inverse-variance weighted (IVW)24, weighted median (WM)25, and MR-Egger26. IVW is the conventional and primary method, assuming that all the IVs are valid and exploiting the inverse of the variance of the IV estimates to give more weight to more precise MR estimates24. However, it is sensitive to invalid instruments and may produce biased MR estimates if any of the genetic variants violate the core MR assumptions. WM method provides a more robust estimate by calculating a median-based effect size, thereby lessening the influence of potentially invalid instruments. WM has the added advantage of providing consistent estimates even when up to 50% of the weight comes from invalid instruments25. MR-Egger method employs a modified IVW approach with an unconstrained intercept in the regression model, which allowed the estimate to capture the average pleiotropic effect across genetic variants. By offering insights into pleiotropic effects, MR-Egger adds a layer of robustness to the causal inference26. These methods offer complementary perspectives, enhancing the study’s credibility and rigor in exploring the causal relationships under investigation.

We also perform sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of MR estimates. Cochran’s Q statistic evaluates heterogeneity among individual IVs, which tested the coherence of their causal effects. A significant Q statistic indicates substantial heterogeneity and suggests that different genetic variants may be exerting differential effects on the outcome27. When significant heterogeneity existed, we will perform random-effects model of IVW to reduce bias. The intercept of the MR-Egger regression serves as an indicator of horizontal pleiotropy. A significant deviation of the intercept from zero suggests the presence of unbalanced pleiotropy, which can bias MR estimate26. Mendelian Randomization Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier (MR-PRESSO) is method to detect and correct for pleiotropic outliers28. If detected outliers, we will remove the outlier variants to produce corrected causal estimates. This method enhances the reliability of the MR analysis by minimizing pleiotropic bias and adjusted heterogeneity. The leave-one-out analysis adds robustness by excluding each IV one at a time and recalculating the MR estimate29. This helps identify any single SNP that may influence the overall causal MR estimates, thereby revealing potential sources of bias. The funnel plot serves as graphical tools to assess asymmetry and heterogeneity among the instrumental variables. Asymmetry may indicate directional pleiotropy.

Additionally, we conduct reverse MR, where the outcome of interest is treated as the exposure, and genetic variants associated with the rosacea are used to infer the causal effect on the original exposure. Reverse MR anlysis follows the same principles as standard MR, using genetic variants significantly associated with the outcome as IVs in the reverse direction. This complementary approach enhances the robustness of causal inference and provides a more comprehensive understanding of bidirectional relationships between traits or diseases.

Results

Genetic instruments for rosacea

Initially, the genome-wide significant threshold resulted in the identification of only a few SNPs. Consequently, we relaxed the threshold to 5 × 10–6, which allowed us to identify 17 SNPs that exhibited a significant association with rosacea. One SNP (rs11741255) was excluded using PhenoScanner V2 for its potential confounding effects. The final SNPs associated with rosacea are detailed in Table 2. All the F-statistics for the included SNPs were greater than 10, indicating no weak instrument bias in our study. In addition, the range of R2 is from 0.77% to 1.74%.

Forward MR estimates and sensitivity analyses

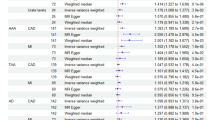

The primary MR results were depicted in Fig. 2.

According to the IVW result, we found that rosacea is associated with an elevated risk of HTN (OR = 1.0032, 95% CI [1.0001–1.0063], P = 0.04). The MR-Egger (OR = 1.0034, 95% CI [0.9965–1.0104], P = 0.35) and WM (OR = 1.0035, 95% CI [0.9996–1.0073], P = 0.08) methods yielded inconsistent results (Figure S1D, Figure S2D). Cochrane’s Q statistic revealed no considerable heterogeneity in the SNP estimates (P = 0.21) (Fig. 2, Table S1). Furthermore, the leave-one-out analysis did not reveal that MR results were significantly affected by individual SNPs (Figure S3D). Both MR-Egger’s intercept (P = 0.96) (Fig. 2) and MR-PRESSO (global P = 0.28) indicated the absence of significant polymorphism (Table S2). Moreover, a symmetrical funnel plot validated the robustness of the MR estimates (Figure S4D).

IVW analysis showed no causal relationship between rosacea and AF (OR = 1.0099, 95% CI [0.9823–1.0382], P = 0.49), CAD (OR = 1.0138, 95% CI [0.9824–1.0462], P = 0.39), HF (OR = 0.9965, 95% CI [0.9671–1.0268], P = 0.82), IS (OR = 0.9933, 95% CI [0.9545–1.0337], P = 0.74), or MI (OR = 1.0001, 95% CI [0.9988–1.0013], P = 0.92) (Fig. 2). In the sensitivity analysis, significant heterogeneity was revealed in the MI subgroup according to the Cochran’s Q test. Other sensitivity analysis showed that the IVs used in our study did not exhibit heterogeneity (P > 0.05) of pleiotropy (P > 0.05), as presented in Table S1 and Figure S2.

Reverse MR estimates and sensitivity analyses

The results of the reverse MR analysis are presented in Fig. 3. In this analysis, most of the IVs derived from HTN and MI had F-statistics below 10, indicating weak instruments. As a result, we excluded HTN and MI from the reverse MR analysis. Additionally, we found no genetic effects of CVDs on rosacea, including AF (OR = 0.9911, 95% CI [0.8808–1.1151], P = 0.88), CAD (OR = 1.1128, 95% CI [0.9295–1.3324], P = 0.24), HF (OR = 1.1292, 95% CI [0.6544–1.9484], P = 0.66), and IS (OR = 1.2169 , 95% CI [0.7418–1.9963], P = 0.44). Sensitivity analysis confirmed the stability of our results, with scatter plots, leave-one-out plots, and funnel plots provided in Supplementary Figures S5-S8.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first MR study to systematically investigate the causal relationships between rosacea and the risk of various CVDs. In the present study, we identified significant associations between rosacea and HTN. However, the associations with other cardiovascular outcomes (AF, CAD, HF, IS, and MI) were not statistically significant. Additionally, there is no evidence to suggest that CVDs (AF, CAD, HF, and IS) are causally related to rosacea risk.

So far, mounting comorbidities of rosacea have been identified, suggesting that rosacea is not simply a skin disease but has links to multiple systemic illnesses30. Previous evidence on association of rosacea with the risk of HTN primarily originates from retrospective cohort studies. A recent meta-analysis31 of 5 trials observed a notable positive association between rosacea and the risk of HTN with risk ratios (RR) = 1.20 (95%CI, 1.08–1.34, P < 0.01) (I2 = 68.5%, P = 0.013). Substantial difference on the risk of HTN was observed between previous findings and our results (20% vs. 0.3%). This disparity may be attributed to systematic biases in these observational studies.

Neurovascular dysfunction is a major component of the pathogenesis of rosacea, and its key process is the activation of transient receptor potential channels (TRPs), which are non selective Ca2+channels. TRPs can respond to various stimuli, some of which are common causes of rosacea. For example, transient receptor potential vanilloid (TRPV)-1 can respond to stimuli such as heat, emotional stress, and capsaicin32. Activation of TRPV4 may cause vasodilation, leading to redness and erythema in rosacea33. TRPs are also expressed in various cell types, including sensory neurons, mast cells, and endothelial cells. Prior studies ample evidence that activation of the sympathetic nervous system and vascular alterations triggered by transient receptor potential ion channels contribute significantly to the pathogenesis of HTN34,35. Furthermore, research in patients with rosacea has revealed that the transient receptor potential vanilloid subfamily potentiates immune reactivity, thus highlighting the shared mechanism between rosacea and HTN36.

Our MR study found a causal association between rosacea and an increased risk of HTN in the European population, with an OR of 1.0032. While this effect size is statistically significant, it is relatively small, raising concerns about its clinical relevance. However, even modest effect sizes can have substantial public health implications, particularly when the risk factor, like rosacea, is prevalent1,2,31. A slight increase in risk, when applied to large populations, can result in a considerable number of additional cases. In this context, even a small elevation in HTN risk among individuals with rosacea could contribute significantly to the cardiovascular disease burden over time. Moreover, small genetic effects are often observed in complex, multifactorial diseases37 such as HTN, where multiple factors interact to influence risk. The cumulative effect of these small risks across a large population can lead to significant long-term health consequences. Therefore, effective management of rosacea could help prevent HTN and its associated disease burden in the general population.

In addition, the meta-analysis reported a null association between rosacea and the subsequent risk of MI and stroke31. Meanwhile, a recent retrospective cohort study10 involving 2,681 patients illustrated that the risk of stroke did not significantly increase in individuals with rosacea, either. It is consistent with our results. However, for the risk of CAD, the retrospective cohort studies found a significant increase in the individuals with rosacea7,10. This discrepancy may be partly attributed to unrecognized confounding factors in retrospective cohort study, as well as population differences. Our MR analysis which can largely circumvent confounding bias showed no association between rosacea and CAD. Since rosacea susceptibility was modulated by race and sex, the role of rosacea for CAD in different populations may require further investigation.

Overall, our study possesses several strengths that contribute to resolving the conflicting results present in current observational research31. First, the MR approach provides a robust mechanism to mitigate the intrinsic biases that plague observational studies, including confounding variables, reverse causality, and regression dilution. Second, the employment of extensive GWAS datasets enhances our study’s statistical power, thereby increasing the validity of our causal inferences. Third, we employed a rigorous approach to SNP selection, such as F-value calculations and PhenoScanner V2. Additionally, we applied the MR-PRESSO method for MR estimate adjustment to minimize potential biases inherent in MR analyses.

The study is subject to several limitations that warrant consideration. Firstly, our MR analysis was confined to the European population, and as such, the findings may not be directly applicable to non-European populations. Due to the lack of relevant databases, conducting an MR analysis of rosacea and CVDs in non-European populations is not feasible with the current data availability. In addition, although we took measures to mitigate the effects of heterogeneity by excluding known SNPs related to CVDs and other confounders, the potential for residual heterogeneity cannot be completely ruled out. Furthermore, in the reverse MR analysis, most of the IVs derived from HTN and MI had F-statistics below 10, indicating weak instruments. As a result, we did not perform reverse MR analysis for HTN and MI. Finally, it should be noted that our study only provides genetic evidence, and does not account for environmental factors that may influence the relationship between rosacea and CVDs.

Conclusion

Our study systematically investigated the potential association between genetically determined rosacea and CVD risk and revealed the potential causal relationship between rosacea and an increased risk of HTN. These findings contribute to a more nuanced understanding of rosacea pathophysiology and emphasize the importance of a comprehensive CVD risk assessment and intervention strategy for patients with rosacea. Such insights could inform more integrated cardiovascular prevention strategies for rosacea populations, focusing not only on inflammation mitigation but also on the management of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. While we eagerly anticipate future research endeavors aimed at reducing CVD-related morbidity in patients with rosacea, the magnitude of the observed causal effects advises a cautious interpretation of the MR estimates presented in this study. Additionally, future MR studies in non-European populations will be crucial to confirm the generalizability and applicability of these findings across diverse genetic backgrounds.

Data availability

The data used in this study was obtained from public databases and previous studies. Further information is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- AF:

-

Atrial fibrillation

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- CIs:

-

Confidence intervals

- CVDs:

-

Cardiovascular diseases

- GWAS:

-

Genome-Wide Association Study

- HF:

-

Heart failure

- HTN:

-

Hypertension

- IS:

-

Ischemic stroke

- LD:

-

Linkage disequilibrium

- IVs:

-

Instrumental variables

- IVW:

-

Inverse-variance weighted

- MAF:

-

Minor allele frequency

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- MR:

-

Mendelian randomization

- MR-PRESSO:

-

MR-Pleiotropy Residual Sum and Outlier

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- RR:

-

Risk ratio

- SNPs:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- TRPs:

-

Transient receptor potential channels

- TRPV:

-

Transient receptor potential vanilloid

- WM:

-

Weighted median

References

Kyriakis, K. P. et al. Epidemiologic aspects of rosacea. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 53, 918–919 (2005).

Geng, R. S. Q., Bourkas, A. N., Mufti, A. & Sibbald, R. G. Rosacea: Pathogenesis and therapeutic correlates. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 28(2), 178–189 (2024).

Yamasaki, K. et al. Increased serine protease activity and cathelicidin promotes skin inflammation in rosacea. Nat. Med. 13, 975–980 (2007).

Steinhoff, M., Schauber, J. & Leyden, J. J. New insights into rosacea pathophysiology: a review of recent findings. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 69, S15-26 (2013).

Kim, J. Y. et al. Increased expression of cathelicidin by direct activation of protease-activated receptor 2: possible implications on the pathogenesis of rosacea. Yonsei Med. J. 55, 1648–1655 (2014).

Holmes, A. D., Spoendlin, J., Chien, A. L., Baldwin, H. & Chang, A. L. S. Evidence-based update on rosacea comorbidities and their common physiologic pathways. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 78, 156–166 (2018).

Hua, T.-C. et al. Cardiovascular comorbidities in patients with rosacea: A nationwide case-control study from Taiwan. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 73, 249–254 (2015).

Egeberg, A., Hansen, P. R., Gislason, G. H. & Thyssen, J. P. Assessment of the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with rosacea. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 75, 336–339 (2016).

Marshall, V. D., Moustafa, F., Hawkins, S. D., Balkrishnan, R. & Feldman, S. R. Cardiovascular disease outcomes associated with three major inflammatory dermatologic diseases: a propensity-matched case control study. Dermatol. Ther. (Heidelb). 6, 649–658 (2016).

Choi, D., Choi, S., Choi, S., Park, S. M. & Yoon, H.-S. Association of rosacea with cardiovascular disease: A retrospective cohort study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 10, e020671 (2021).

Vieira, A. C. C., Höfling-Lima, A. L. & Mannis, M. J. Ocular rosacea—A review. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 75, 363–369 (2012).

Yuan, X. et al. Relationship between rosacea and dietary factors: A multicenter retrospective case-control survey. J. Dermatol. 46, 219–225 (2019).

Didelez, V. & Sheehan, N. Mendelian randomization as an instrumental variable approach to causal inference. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 16, 309–330 (2007).

Jin, T. et al. Inferring the genetic effects of serum homocysteine and vitamin B levels on autism spectral disorder through Mendelian randomization. Eur. J. Nutr. 63(3), 977–986 (2024).

Burgess, S. et al. Using published data in Mendelian randomization: A blueprint for efficient identification of causal risk factors. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 30, 543–552 (2015).

Kurki, M. I. et al. FinnGen: Unique genetic insights from combining isolated population and national health register data. Genet. Genom. Med. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.03.22271360 (2022).

Nielsen, J. B. et al. Biobank-driven genomic discovery yields new insight into atrial fibrillation biology. Nat. Genet. 50, 1234–1239 (2018).

Van Der Harst, P. & Verweij, N. Identification of 64 novel genetic loci provides an expanded view on the genetic architecture of coronary artery disease. Circ. Res. 122, 433–443 (2018).

Shah, S. et al. Genome-wide association and Mendelian randomisation analysis provide insights into the pathogenesis of heart failure. Nat. Commun. 11, 163 (2020).

Sakaue, S. et al. A cross-population atlas of genetic associations for 220 human phenotypes. Nat. Genet. 53, 1415–1424 (2021).

Dönertaş, H. M., Fabian, D. K., Fuentealba, M., Partridge, L. & Thornton, J. M. Common genetic associations between age-related diseases. Nat. Aging 1, 400–412 (2021).

Shen, S., Gao, X., Song, X. & Xiang, W. Association between inflammatory bowel disease and rosacea: A bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 90, 401–403 (2024).

Kamat, M. A. et al. PhenoScanner V2: An expanded tool for searching human genotype-phenotype associations. Bioinformatics 35, 4851–4853 (2019).

Lawlor, D. A., Harbord, R. M., Sterne, J. A. C., Timpson, N. & Davey, S. G. Mendelian randomization: Using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology. Stat. Med. 27, 1133–1163 (2008).

Bowden, J., Davey Smith, G., Haycock, P. C. & Burgess, S. Consistent estimation in mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet. Epidemiol. 40, 304–314 (2016).

Bowden, J., Davey Smith, G. & Burgess, S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44, 512–525 (2015).

Greco, M. F. D., Minelli, C., Sheehan, N. A. & Thompson, J. R. Detecting pleiotropy in Mendelian randomisation studies with summary data and a continuous outcome: Detecting pleiotropy in Mendelian randomisation studies with summary data and a continuous outcome. Statist Med. 34, 2926–2940 (2015).

Verbanck, M., Chen, C.-Y., Neale, B. & Do, R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat. Genet. 50, 693–698 (2018).

Carrasquilla, G. D., García-Ureña, M., Romero-Lado, M. J. & Kilpeläinen, T. O. Estimating causality between smoking and abdominal obesity by Mendelian randomization. Addiction (2024).

Haber, R. & El Gemayel, M. Comorbidities in rosacea: A systematic review and update. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 78, 786-792.e8 (2018).

Chen, Q. et al. Association between rosacea and cardiometabolic disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 83, 1331–1340 (2020).

Cui, M. et al. TRPV1 receptors in the CNS play a key role in broad-spectrum analgesia of TRPV1 antagonists. J. Neurosci. 26, 9385–9393 (2006).

Baylie, R. L. & Brayden, J. E. TRPV channels and vascular function. Acta Physiol. (Oxf). 203, 99–116 (2011).

Norlander, A. E., Madhur, M. S. & Harrison, D. G. The immunology of hypertension. J. Exp. Med. 215, 21–33 (2018).

Touyz, R. M. et al. Vascular smooth muscle contraction in hypertension. Cardiovasc. Res. 114, 529–539 (2018).

Two, A. M., Wu, W., Gallo, R. L. & Hata, T. R. Rosacea: part I. Introduction, categorization, histology, pathogenesis, and risk factors. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 72, 749–758 (2015).

Zhang, J. et al. Association between type 1 diabetes mellitus and ankylosing spondylitis: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front. Immunol. 14, 1289104 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to all the researchers who contributed to this MR study, and we appreciate the institutions and respective researchers who generously provided the data for this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Medical Health Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Provincial Health Commission (2020KY443 and 2023KY044), State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of the People’s Republic of China-Zhejiang Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine Joint Science and Technology Program Project (00004ACGZYZJKJ23055), and the China Rehabilitation Research Center Scientific Research Fund(2024ZX-02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yafang Gao and Chengan Xu: Conceived the idea, performed the MR analysis, and participated in manuscript writing. Qiqi Yan: Supervised the study, and provided final approval of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Each participant received ethical approval and informed consent for the respective study, as detailed in the original publication and consortium.

Consent for publication

No conflict of interest exists in the submission of this manuscript, and the manuscript is approved by all authors for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, Y., Xu, C. & Yan, Q. Genetic analyses reveal association between rosacea and cardiovascular diseases. Sci Rep 15, 6657 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91240-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91240-4