Abstract

To evaluate the influence of mining face width on the fracture characteristics of overlying rock strata, a mechanical model of overlying rock strata before fracture is established based on Winkler’s elastic foundation hypothesis. This model incorporates Timoshenko’s solution to calculate the variation of bending moment and shear force under different foundation conditions. The physical experimental results reported in relevant literature have also verified that the overlying rock strata are fractured with trapezoidal structure. Subsequently, the relevant parameters of this trapezoidal spatial structure about overlying rock strata before and after periodic roof weighting are analyzed in detail, and the calculation results show that the height of trapezoidal spatial structure is directly affected by the width of mining face, and the fractured form of rock layers changes from a horizontal “O-X” structure to a vertical “O-X” structure from the bottom up. Afterwards, the stability verification of inferior key layers is conducted following the trapezoidal spatial structure. Based on elastic thin plate theory, the mine pressure characteristics are analyzed, and the relationship curve of hanging length and hanging width of any rock layer in the overlying rock strata is obtained. Finally, the influence analysis of mining face width on type selection of hydraulic support is demonstrated based on the Panels 1302 and 1305 belonging to Zhaozhuang No.2 underground mine, and the on-site engineering application effect is significant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Modern mining operations extend to large depth resulting in significant mining height, which increases the demand on the hydraulic supports required for the mining face. Existing research generally simulates the hydraulic supports assuming beam structure, with less consideration given to the influence of working face width. In fact, the popularity of the large mining height technology is often accompanied by an increase in the concentration of mining production; in this process, the width of a mining face also significantly increases. At present, the mining face width of mines in China is generally greater than 300 m. For example, mines belonging to Shendong Coal have successively achieved working faces mining operation with a width of 360 m (Yujialiang Colliery), 400 m (Shangwan Colliery), and 450 m (Halagou Colliery). The available statistics demonstrate that as the width of a mining face increases, the period presses step distance of the working face decreases and the load on the hydraulic supports increases during non pressure periods. In addition, the overall intensity of mining pressure manifestation intensifies, and the impact load formed by the period presses becomes much greater than the maximum operating resistance of the hydraulic supports. Thus, the change in the width of mining faces has a significant influence on the characteristics of mining pressure, and the previous simplified analysis of mining pressure as a beam structure could not fully consider the influence of mining face width, making it difficult to fully explain the changes in mining pressure intensity1,2.

To evaluate the influence of mining face width, the structural fracture characteristics of the overlying rock strata should be studied first. Both the physical experiments and on-site measurement results indicate that the shape of the overlying rock strata after the fracture of layered rock mass can be approximated as a trapezoidal spatial structure3,4. For example, Qian et al.5 have proposed the O-shaped ring model, Liu et al.6 have proposed the high-level fracture ring model, in addition to the ∩-shaped high cap model7,8, the O, S, C and θ spatial structures9,10, the OX-F-T evolution model11, the trapezoidal spatial structure12 and the shape of elliptical throwing belts13. These studies have analyzed the spatial morphology of overlying rock strata in detail, and have been applied in gas extraction, rock burst prevention and control, goaf retaining roadway testing or on-site practice. However, there is scarce research on the relationship between fracture characteristics of the overlying rock strata and the strength of mining pressure manifestation. The statistical results obtained from actual projects indicate that when the rock layers contained within overlying rock strata fracture in sequence form bottom to top, the suspended width of rock layers gradually decreases with the increase of overlying rock strata fracture height. When the overlying rock strata reaches a certain fracture height and the corresponding suspended width of the top rock layer is less than its own ultimate fracture width, this rock layer will not fracture. Therefore, the actual fracture morphology of the overlying rock strata should be considered, and the variation in the width of a mining face also needs to be taken into account when investigating the manifestation characteristics of mining pressure. This offers a more rigorous alternative approach to simplifying the overlying rock strata as a beam structure.

Based on the above discussion, this paper first analyzes the fracture characteristic of overlying rock strata by constructing a trapezoidal spatial structure. The formation conditions of this trapezoidal spatial structure in overlying rock strata is then analyzed. Consequently, a methodology is developed for calculating the main parameters of this trapezoidal spatial structure before and after periodic roof weighting. Finally, based on the fracture characteristic of overlying rock strata, the influences of mining face width on the spatial fracturing and mining pressure characteristics of the overlying rock strata are evaluated. A comparative analysis is conducted on the manifestation strength of mining pressure before and after considering the spatial fracture morphology of the overlying rock strata considering practical situations, and it is also verified through on-site practice.

Formation mechanism of trapezoidal spatial structure

Analysis of formation mechanism

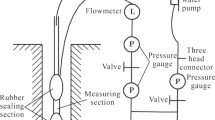

When a working face is mined out, the overlying rock strata above it fractures and caves into the gob, then a trapezoidal spatial structure would form in the overlying rock strata. The relative position of each rock layer in overlying rock strata can be explained according to Winkler’s elastic foundation hypothesis14,15, and the mechanical model of overlying rock strata before fracture can be established as shown in Fig. 1.

Mechanical model of overlying rock strata before fracture. q is the lateral uniform load applied to semi-infinite beam A, N’ and Q’ are respectively the x-axis force and shear force caused by the already fractured and rotationally stable beam B, Q0, M0 and N0 are respectively the shear force, bending moment and x-axial force in the cross-section at x = 0 m, F is the support resistance caused by hydraulic support, l is the distance between the support resistance point and coal rib, L is the length of cantilever beam, k is the modulus of subgrade reaction of foundation strata.

The mechanical model presented in Fig. 1 assumes that the rock layers below the target rock layer can be seen as foundation strata, and the vertical compressive stress sustained by the foundation strata can be expressed as:

where P is the vertical compressive stress sustained by the foundation strata; k is the modulus of subgrade reaction of foundation strata, which reflects the proportional coefficient of displacement increasing with the load; yf is vertical compressive displacement of foundation strata.

A mechanical model is established for the target rock layer adopting the advanced position of mining face as a vertical baseline (y-axis), and the horizontal baseline (x-axis) taken parallel to the advanced direction of target rock layer. Correspondingly, a coordinate system is established as shown in Fig. 1. The target rock layer can be seen as a semi-infinite beam A, and the cantilever length of this semi-infinite beam is defined as L, which means the x-axis value of cantilever end is − L. The semi-infinite beam is also subjected to lateral uniform load (q) which is caused by overlying soft strata, and x-axial force (N’) which is caused by beam B. Referring to Timoshenko’s solution16, the bending deformation differential equation of this semi-infinite beam can be given by:

where E is the elasticity modulus of this semi-infinite beam; I is the inertia moment of this semi-infinite beam; N is the x-axial force in any cross section of this semi-infinite beam.

In order to intuitively analyze the stress and deformation relationships of this semi-infinite beam, the relevant parameters are evaluated according to values proposed in the literature17, i.e., the unit weight of overlying strata (γ) takes a value of 25.0 kN/m3, the thickness of overlying soft strata (h1) takes a value of 2.0 m, the thickness of semi-infinite beam (h2) takes a value of 4.0 m, the elastic modulus of semi-infinite beam takes a value of 30.0 GPa, the moment of inertia of semi-infinite beam takes a value of 5.33 m4, and the tensile strength of semi-infinite beam takes a value of 6.0 MPa. The bending moment (M0) and shear force (Q0) in the cross-section at x = 0 m can be calculated according to the cantilever beam length (L) of 5.6 m. The modulus of subgrade reaction (k) of foundation strata can be taken as 100 MPa, 1000 MPa, 3000 MPa and 6000 MPa as examples, and the mathematical expressions of bending moment (M) and shear force (Q) in any cross-section of this semi-infinite beam A are shown in Table 1 according to Eqs. (1) and (2).

According to the mathematical expressions of bending moment (M) and shear force (Q), the corresponding curves of bending moment (M) and shear force (Q) in any cross-section of this semi-infinite beam can be obtained as shown in Fig. 2.

Curves I in Fig. 2a,b demonstrate that when the modulus of subgrade reaction of foundation strata is small (i.e., 100 MPa), it cannot provide sufficient shear resistance for the semi-infinite beam A, and the fracture of semi-infinite beam is mainly affected by bending moment, and the fracture occurs at the location of maximum bending moment. On the other hand, Curves IV in Fig. 2a,b reveal that when the modulus of subgrade reaction of foundation strata is relatively large (i.e., 6000 MPa), it does allow high bending moment for the semi-infinite beam, and its fracture is mainly affected by shear force, and the fracture occurs at the location of maximum shear force. As the modulus of subgrade reaction of foundation strata increases, the maximum bending moment decreases and the corresponding location of maximum bending moment moves closer to the vertical baseline (y-axis) gradually. Meanwhile, the maximum shear force increases, and the corresponding location of maximum shear force also moves closer to the vertical baseline (y-axis) gradually.

When the coal seam is viewed as foundation strata, its modulus of subgrade reaction is relatively small and the main influence factor for fracture of semi-infinite beam above coal seam is bending moment. Meanwhile, the corresponding fracture location is mainly determined by the maximum bending moment. The small modulus of subgrade reaction of coal seam will cause the fracture location of semi-infinite beam to move closer to the coal wall of mining face, and the fracture location of semi-infinite beam is usually located 3–5 m in front of the coal wall (curves I in Fig. 2a,b). Moreover, when any rock layer above coal seam is viewed as foundation strata, and the modulus of subgrade reaction of any rock layer is relatively large and does not differ much, the main influence factor for fracture of semi-infinite beam above foundation strata is the combined action of bending moment and shear force. In this case, the fracture location of semi-infinite beam is closer to the coal wall than the case of a coal seam as foundation strata (curves II, III, IV in Fig. 2a,b).

Considering that there is a fracture angle during the fracture period of any rock layer above a coal seam, that is, the upper surface of a rock layer will extend to the gob relative to the lower surface, and then the outline of a trapezoidal spatial structure will be formed in the overlying rock strata. In combination with the foregoing analysis, the outline of a trapezoidal spatial structure is usually located within 5 m from the coal wall of mining face. In general, the larger the strength of any rock layer is, the smaller the fracture angle is, and the corresponding trapezoidal spatial structure which is formed in the overlying rock strata is more obvious.

Physical similarity simulation experiments are often used to study the migration laws of overlying rock strata. The typical results of two-dimensional and three-dimensional physical similarity simulations of Sun et al.3, Ju et al.4 are respectively shown in Figs. 3 and 4.

Due to the existence of fracture angle for rock layers above the coal seam, the overlying rock strata will fracture after the coal seam is mined out and then a trapezoidal plane structure is formed above the gob, as observed from Fig. 3. It is also noted from Fig. 4 that the overlying rock strata will fracture after the coal seam is mined out and then a trapezoidal spatial structure is formed above the gob. The typical results of two-dimensional and three-dimensional physical similarity simulation both indicate that the overlying rock strata are fractured with trapezoidal structure. Therefore, the fracture characteristics of trapezoidal structure for overlying rock strata can be further analyzed.

Analysis of main parameters

When the lithology of rock layers in the overlying rock strata are different, the overlying rock strata above gob will fracture and form a trapezoidal spatial structure due to the existence of fracture angle. Therefore, it is assumed that the base angle of a trapezoidal spatial structure is equal to the average fracture angle (α) of the overlying rock strata. It is easy to see that the smaller the average fracture angle is, The size of upper surface of the trapezoidal spatial structure decreases as α decreases, which means the hanging area of an unbroken rock layer is relatively small, and it is not susceptible to fracture under this condition. When the width of mining face is relatively small and the overlying rock strata above gob is hard, the corresponding angle α and the hanging area of an unbroken rock layer are also small. Therefore, it is more practical to calculate the breakage dimension of overlying rock strata considering a trapezoidal spatial structure, which allows more accurate evaluation of loading layers thickness that is more applicable to the subsequent mine pressure analysis. It is assumed that the main roof is regarded as the lower surface of a trapezoidal spatial structure, and its relevant parameters for overlying rock strata before and after periodic roof weighting are shown in Fig. 5.

As shown in Fig. 5, each rock layer contained within overlying rock strata is sequentially numbered from the bottom up, for example, i.e., 1,..., j,..., i,..., n, n + 1.

Analysis of main parameters before periodic roof weighting

Considering the space geometry, the upper surface width of the trapezoidal spatial structure before periodic roof weighting can be expressed as Eq. (3).

where \({W_{n+1}}\) is the upper surface width of the trapezoidal spatial structure; \({W_j}\) is the lower surface width of the trapezoidal spatial structure; \(\sum\limits_{{i=j}}^{n} {{h_i}}\) is the overall height of the trapezoidal spatial structure; \(\alpha\) is the base angle of the trapezoidal spatial structure.

Similarly, the upper surface length of the trapezoidal spatial structure before periodic roof weighting can be expressed as Eq. (4).

where \({L_{n+1}}\) is the upper surface length of the trapezoidal spatial structure; \({L_j}\) is the lower surface length of the trapezoidal spatial structure.

According to Eqs. (3) and (4), when the width of mining face is small, the corresponding lower surface width of the trapezoidal spatial structure is also small, and the upper surface width of the trapezoidal spatial structure which is located in the original position is also small. Thus, this rock layer which is at height \(\sum\limits_{{i=j}}^{n} {{h_i}}\) will not fracture because the overhanging width is too small and the height of trapezoidal spatial structure is directly affected by the width of mining face.

Analysis of main parameters after periodic roof weighting

As the mining face advances, the overlying rock strata above gob are beginning to fracture when the overhanging length of any rock layer in the overlying rock strata is large enough along advancing direction. Observations for a large number of mining projects indicate that a group of rock layers below the main roof will directly fracture and collapse into the gob behind the mining face18,19. Soon afterwards, the main roof will fracture and collapse into the gob, and the overlying soft strata above main roof will move in coordination with the main roof. The inferior key strata lag behind the main roof fracturing, and a separation zone will form between the inferior key strata and overlying soft strata. Hence, it is more efficient to only investigate the behavior of the trapezoidal spatial structure below the inferior key strata which has the greatest influence on the variation of the mine pressure of mining face (as shown in Fig. 5b). During the periodic roof weighting, any rock layer can be regarded as a thin panel with three sides fixed and one side free, and the upper surface length of the trapezoidal spatial structure at periodic roof weighting is equal to the periodical breaking span of main roof, as shown in Eq. (5).

where \({l_j}\) is the periodical breaking span of main roof.

During the periodic roof weighting, when the advancing distance of mining face along the advancing direction is relatively large, the corresponding length of the upper surface of trapezoidal spatial structure is large, but its corresponding width is limited. The schematic of periodic roof weighting during the working face mining period is shown in Fig. 6.

According to Fig. 6, during the period of periodic roof weighting, if the main roof and the overlying soft strata fracture and collapse into the gob behind the mining face, but the gangues cannot fill the gob, and the allowable bending subsidence of the inferior key strata is less than the height of the free space below, then the inferior key strata will form a large area of overhanging roof along the advancing direction20. As the overlying rock strata above this working face fractures in the form of a trapezoidal spatial structure, i.e., the fractured form of rock layers changes from a horizontal “O-X” structure to a vertical “O-X” structure from the bottom up (as shown in Fig. 6a). The fractured form of any rock layer is mainly affected by the overhanging width; when the overhanging width is relatively large, a fractured form of horizontal “O-X” structure occurs, and when the overhanging width is relatively small, a fractured form of vertical “O-X” structure occurs. As the fractured height of the overlying rock strata increases, there would be always a stable rock layer, no matter how long the advancing distance is, and the fractured height of the overlying rock strata no longer develops. That is, when the upper surface width of the trapezoidal spatial structure is less than the limit breaking span, the fractured height of the overlying rock strata will not increase, as shown in Eq. (6)21.

where \({({l_m})_{n+1}}\) is the limit breaking span of rock layer (n + 1); \({h_{n+1}}\) is the thickness of rock layer (n + 1); \({({\sigma _t})_{n+1}}\)and \({K_{n+1}}\)are its tensile strength and tensile strength coefficient; \({q_{n+1}}\) is the vertical uniform load due to rock layer (n + 1).

Without considering the weathering, water softening and damage degree of the overlying rock strata, no matter how long the advancing length is, rock layers (n + 1) will not fracture, i.e., rock layer (n + 1) can be called stable inferior key strata.

Influence of mining face width on strata behaviors

Spatial effects of mining face width

If the overlying rock strata above a working face are fractured in the shape of a trapezoidal spatial structure, the overhanging width of the strata above will gradually decrease as the overall height of the trapezoidal spatial structure increases22,23. When the overhanging width of a rock layer at a higher level is less than the limit breaking span, this rock layer may fracture according to the beam structure theory rather than in a trapezoidal spatial structure. The influence of mining face width on the spatial fracture characteristics of overlying rock strata is called the spatial effect of mining face width.

The analysis in subsection 2.2 indicates that during the initial incoming pressure, each rock formation overlying the mining face can be simplified as a four-sided solidly supported sheet, with the long side of the sheet spanning in the direction of the working face and the short side spanning in the direction of advancement. Considering the trapezoidal spatial structure breakage characteristics of the overlying rock, the exposed length of each rock layer in the overlying rock of the working face decreases from bottom to top along the direction of strike and tendency. Meanwhile, the ultimate breakage step distance of the exposed rock layer increases with the decrease of the exposed width in the width direction of the working face. Consequently, the loading layer determined according to the beam theory may not have been broken in space, and the height of trapezoidal spatial structure is actually smaller. Similarly, the rock layers in the overburden layer on the working face during the period of cyclic compression can be simplified as a thin plate with three sides fixed and one side free, in which case the span of the overburden rock along the width of the working face decreases. This leads to an increase in the ultimate breakage step, and consequently, the thickness of the rock layer where the breakage occurs becomes smaller relative to the theoretically determined value of the beam. This effect on the spatial break-up characteristics of the overburden rock due to the width of the mining face is called “spatial effects of mining face width”.

Influence of mining face width on the manifestation of mining pressure

Trapezoidal Spatial structure height and related key layer theory

According to the conventional key layer theory, a key layer is thick and hard, and is able to coordinate deformation with the overlying loading layer, i.e., breaking synchronously and lagging behind the breaking of the key layer below. Based on the stiffness and strength considerations, the key layers in overburden should satisfiy the following conditions24:

where \({E_n}\) is the elastic modulus of rock layer n; \({\gamma _n}\) and \({h_n}\) are its unit weight and thickness; \({q_{(n+1)|1}}\) and \({q_{n|1}}\) are the loads on the first key layer when analyzing rock layers (n + 1) and n, respectively; \({l_j}\) is the breaking span of No. j hard rock layer.

Meanwhile, on-site drilling measurements and laboratory simulations confirm that the subcritical layer in the overburden does not apply loads to the base roof before breaking, and does not apply loads to the base roof when the breakage occurs at a location lagging the mining face. Based on the masonry beam theory16, the basic roof in the overburden above the mining face is in the abscission layer zone; therefore, no load is applied to the basic roof before the sub-critical layer breaks. The fractured structure of overlying rock layers above working face is shown in Fig. 7.

The key layer theory is used to accurately identify the thick and hard rock layers that control the activity of overlying strata. Considering that the failure mode of overlying rock is trapezoidal spatial structure, the hanging area of this thick and hard key layer is small and less likely to break compared to simplifying it to a beam structure. This is because when simplifying it as a beam structure, the width of its overhanging plate is assumed to be infinitely long. Therefore, the coordinated deformation and fracture variations between different rock layers should be considered according to the trapezoidal spatial structure, in order to determine the stability of inferior key strata. Thus, analysis should proceed by first identifying the inferior key layers that serve as the “skeleton” of the overlying rock according to the key layer theory. Afterwards, the stability will be verified following the trapezoidal spatial structure.

Analysis of mine pressure characteristics based on elastic thin plate theory

The use of thin plate theory requires the following conditions to be satisfied25:

where \({\eta _r}\) is the thickness to width ratio; h is the thickness of a thin plate; b is the smaller side length of a thin plate.

In addition, due to the brittleness of the rock layer, its bending deflection is assumed to be much smaller than its thickness. Accordingly, the Kirchhoff hypothesis can be used to study the problem of roof fracture. Firstly, a thin plate with four fixed edges can be established, as shown in Fig. 8.

As shown in Fig. 8, the bending deflection at the boundary position of the thin plate satisfies the following Eq. (10).

where w is the bending deflection of a thin plate.

Represent bending deflection w as a double trigonometric series, i.:

where m and n is the positive integer; \({A_{mn}}\) is the correlation coefficient to be solved; \({L_i}\) is the hanging length of any rock layer in overlying strata along the mining direction; \({W_i}\) is the hanging width of any rock layer in overlying strata.

Meanwhile, the bending deflection w should satisfy the deflection curve differential equation, i.e.

where D, E and v are the flexural rigidity, elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio of thin plate; q is the uniformly distributed load on it.

By combining Eqs. (11) and (12), the following equation may be obtained:

The uniformly distributed load q is further expanded into a double trigonometric series, i.e.:

by combining Eqs. (13) and (14), the following equation is obtained:

Combining Eqs. (11) and (15) gives:

In addition, the internal forces of a thin plate can be expressed by:

where \({\sigma _x}\) and \({\sigma _y}\) are the normal stress components along the x and y directions, respectively; and \({\tau _{xy}}\) is the shear stress components parallel to the xoy plane.

Based on Eq. (17), the torque parameters \({M_x}\), \({M_y}\) and \({M_{xy}}\) can be expressed as:

Considering Eq. (16), taking the first term of an infinite series to solve the internal forces of a thin plate, and combining Eqs. (17) and (18), the final expression of the internal forces can be obtained, i.e.,:

where A is a parameter related to the size of the thin plate.

The cloud picture of the internal forces calculated using Eq. (19) (coded in the software Mathematic) for a thin plate is plotted in Fig. 9.

Because the tensile strength of rock materials is much smaller than their shear and compressive strength, the maximum tensile stress criterion is used to determine the fracture of a rock layer. Based on Fig. 9, it is easy to see that, when considering the internal forces of rock layers above the working face according to the thin plate theory, the maximum tensile stress in the rock layer occurs at the plate fixed edge.

The maximum value of principal stress located at the thin plate fixed edge can be given by:

where \({\sigma _{\hbox{max} }}\) is the maximum principal stress of a thin plate.

Meanwhile, according to Fig. 9, shear stress, \({\tau _{xy}}\) = 0 at the fixed boundary of the thin plate, and the maximum principal stress (\({\sigma _x}\) or \({\sigma _y}\)) occurs at the middle of the relatively longer fixed edge. This means as the hanging length of a rock layer in overlying strata along the mining direction (\({L_i}\)) reaches a certain length, \({l_i}\), the maximum tensile stress exceeds its ultimate strength, and the rock layer fractures. The length, \({l_i}\) can be expressed by:

where \({({l_m})_i}\) is the ultimate fracture length when the rock layer i is considered as a fixed beam structure at both ends in the trapezoidal spatial structure; \({h_i}\) is the height of rock layer i in the trapezoidal spatial structure; \({({\sigma _t})_i}\) is its tensile strength; and \({q_i}\) is the vertical uniform load acting on rock layer i before ultimate fracture.

Based on Eq. (21), for rock layer i, the relationship between the hanging length, \({L_i}\), and the hanging width, \({W_i}\), in the trapezoidal spatial structure is plotted in Fig. 10. It is noted from Fig. 10 that as the hanging width of the rock layer decreases, the corresponding periodical breaking span increases.

Based on the discussion in Sect. 2.2, it may be concluded that as the vertical position of rock layer i increases, its corresponding hanging width decreases. At the same time, the hanging width of rock layer i at the same vertical height position is small when the width of the working face is small. Therefore, under the same overlying rock conditions (i.e., \({({l_m})_i}\) is constant), the width of a working face will affect the surface size of the trapezoidal spatial structure, thereby affecting the fracture characteristics of the overlying rock. When the width of the working face changes, the corresponding height of the trapezoidal spatial structure also changes, i.e., when the width of a working face is relatively large, the corresponding fractured height of the overlying rock is also large, and the total thickness of the loading layers is also large, and the resistance of the supports inside the working face increases accordingly.

It is evident that as the width of the working face increases, the corresponding hanging width (\({W_i}\)) of rock layer i in the trapezoidal spatial structure increases, and the rock layers that did not fracture due to their small width of working face also begin to fracture. Hence, it can be shown that the mine pressure strength of a mining face increases in step-wise manner as the width of a working face increases based on on-site measurement statistics26. After obtaining the ultimate fracture length of any rock layer under the condition of thin plate theory, combined with the physical and mechanical properties of any rock layer, it is possible to verify whether the loading layers above the basic roof have fractured, and then calculate the height of the trapezoidal spatial structure.

Additionally, it should be noted that the filling percentage in the gob area reflects the size of the free space between the falling rock blocks and the overlying suspended roof. When the filling degree is good, the suspended roof in the gob area is timely supported, and the fracture height of the overlying rock is controlled. In summary, changes in the width of working face and filling degree of the gob area can cause changes in the periodic intervals of mine pressure and the height of trapezoidal spatial structure in the overlying rock, thereby leading to changes in the mining pressure characteristics of the mining area. For detailed calculations, please refer to the engineering example in the next section.

Influence analysis of mining face width on type selection of hydraulic support

Project profile of panel 1305

Zhaozhuang No.2 underground mine, located in Changzi County, Changzhi City, Shanxi Province, has an annual production capacity of 1.2 million tons. The Panel 1305 in this underground mine mainly mines the No.3 coal seam, with a mining face width of 85 m and an advancing length of 298.6 m. The average thickness of No.3 coal seam is about 5.36 m, and its average inclination is 3°. The Panel 1305 adopts the long-wall, large-height, full-height mining method, with a mining depth of 404.6 ~ 409.8 m. During the mining period, the three sides of Panel 1305 are solid coal and the front of its stopping-line is several main roadways. The plane location relationship of Panel 1305 is shown in Fig. 11.

Based on, Table 2 presents the details of the physical and mechanical parameters of No.3 coal seam obtained from the results of relevant geological boreholes in Panel 1305 and the corresponding laboratory tests.

Height determination of trapezoidal Spatial structure based on thin plate theory

Judgment of key strata locations

Based on the structural characteristics of the overlying strata shown in Table 2, it can be concluded that the total thickness of rock strata above the No.3 coal seam (i.e., the mudstone layer (1.8 m), siltstone layer (3.6 m), medium sandstone layer (2.5 m) and siltstone layer (4.4 m)) is relatively small and close to the Panel 1305, and can thus be considered as immediate roof strata. Therefore, the total thickness of the immediate roof strata is given by:

where \(\sum\limits_{{i=1}}^{4} {{h_{bri}}}\) is the total thickness of the immediate roof strata above the Panel 1305; \({h_{br1}}\), \({h_{br2}}\), \({h_{br3}}\), and \({h_{br4}}\) are the thickness of mudstone, siltstone, medium sandstone and siltstone layers above the Panel 1305, respectively.

Zhu et al.27 suggest that the caving height of immediate roof strata is generally 2–2.5 times the mining height of Panel 1305, and results of Eq. (22) satisfies this requirement. Therefore, the fifth layer of fine sandstone with a thickness of 8.8 m above the Panel 1305 may be a main roof. In addition, the criterion for determining whether the fifth layer of fine sandstone belongs to a fault zone is that the thickness of this rock layer should be greater than 1.5 times the height of the free gap below it. Therefore, the following formula can be used to verify whether this rock layer is a main roof.

where \({h_{br5}}\) are the thickness of 8.8 m thick fine sandstone layer above the Panel 1305; \({\Delta _{gap}}\) is the height of the free gap below the fifth layer of fine sandstone; \({H_{cs}}\) is the thickness of 5.0 m thick No.3 coal seam; \({k_p}\) is the expansion factor of immediate roof strata, with a empirical value of 1.35.

Based on Eq. (23), it can be inferred that the fifth layer of fine sandstone with a thickness of 8.8 m is much greater than the height of the free gap below the fifth layer of fine sandstone, which means that the fifth layer of fine sandstone is already within the fault zone and can be recognized as a main roof above the Panel 1305.

After determining that the fifth layer of fine sandstone shown in Table 2 is the main roof, the location of any key strata can be determined based on Eqs. (7) and (8) as demonstrated in Eq. (24).

These results demonstrate that the load of the 5th rock layer itself (\({q_{5|5}}\)) is about 243.0 kPa, the load on the 5th rock layer when calculating to the 6th rock layer (\({q_{6|5}}\)) is about 330.0 kPa, the load on the 5th rock layer when calculating to the 7th rock layer (\({q_{7|5}}\)) is about 396.1 kPa, the load on the 5th rock layer when calculating to the 8th rock layer (\({q_{8|5}}\)) is about 470.0 kPa, and the load on the 5th rock layer when calculating to the 9th rock layer (\({q_{9|5}}\)) is about 148.5 kPa. It is observed that the load on the 5th rock layer when considering the 9th rock layer is smaller than the load on the 5th rock layer when calculating to the 8th rock layer, which means the 6th, 7th, and 8th rock layers will exert a certain load on the 5th rock layer, while the 9th rock layer, due to its high strength and large thickness, will not act as an overlying loading layer and exert a load on the 5th rock layer. Thus, the 9th rock layer can be recognized as an inferior key stratum above the Panel 1305, and the 6th, 7th, and 8th rock layers can be recognized as the overlying loading layers of the 5th rock layer. Similarly, according to Eqs. (7) and (8), it can be determined from Table 2 that the 12th rock layer is also an inferior key stratum.

Calculation of thickness of loading layers above panel 1305

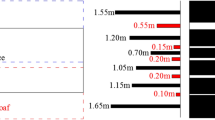

Based on Eqs. (3) and (6), the height of trapezoidal spatial structure above Panel 1305 can be determined. Firstly, the suspended width and limit breaking span of the 9th rock layer can be calculated as follows.

where \({W_5}\) is the lower surface width of the trapezoidal spatial structure with a value of 85.0 m; \(\alpha\) is the base angle of the trapezoidal spatial structure with a value of 60°; \({K_9}\) is the tensile strength coefficient of the 9th rock layer with a value of 0.9.

Equation (25) reveals that the thickness to width ratio of the 9th rock layer is far greater than 0.200, which does not satisfy the conditions of the thin plate theory. Therefore, based on conventional key layer theory calculations, it can be inferred that the suspended width of the 9th rock layer is smaller than its limit breaking span, which means it can maintain a suspended state without breaking and it is a stable inferior key strata. In conclusion, the upper surface of the trapezoidal spatial structure will not exceed the lower surface of the 9th rock layer.

Whether the rock layers below the 9th rock layer (a stable inferior key strata) have broken can be checked and determined from top to bottom in sequence, and the judgment of the 8th rock layer can be made first.

Based on Eqs. (3) and (9), the suspended width of the 8th rock layer and its thickness to width ratio can be calculated as follows.

Based on Eq. (26), it can be inferred that the thickness to width ratio of the 8th rock layer is far less than 0.125, which meets the usage conditions of the thin plate theory. Therefore, based on Eq. (21), the periodical breaking span of the 8th rock layer can be calculated as follows.

where \({K_8}\) is the tensile strength coefficient of the 8th rock layer with a value of 0.8.

Equations (26) and (27) show that for the 8th rock layer, it is necessary for its suspended length to reach 75.5 m before fracture occurs because its width is only 66.8 m. In fact, when the thickness of the loading layers does not consider the unbroken 8th rock layer, the periodical breaking span of the 5th rock layer (a main roof) can be calculated as follows.

where \({K_5}\) is the tensile strength coefficient of the 5th rock layer with a value of 0.8.

Based on Eqs. (27) and (28), the periodical breaking span of the 5th rock layer is smaller than that of 8th rock layer, i.e., \({l_5}\)<\({l_8}\), which means that when the 5th rock layer (a main roof) is broken, the 8th rock layer has not yet broken and does not act on the 5th rock layer in the form of a load. Similarly, the 6th and 7th rock layers in Table 2 could be verified in sequence using the above calculation method. Furthermore, during the periodic weighting period, the 5th, 6th and 7th rock layers may break simultaneously, with a periodical breaking span of 65.1 m. Additionally, considering that the suspended width of the 5th rock layer is greater than its periodical breaking span, the 5th rock layer (a main roof) shows a fractured form of horizontal “O-X” structure.

Based on the above analysis, it can be concluded that during the mining period of Panel 1305, the 9th rock layer (a stable inferior key strata) above Panel 1305 remains in unbreakable state, and the 8th rock layer does not fracture along with the 5th rock layer (a main roof). However, when a periodic fracture occurs in the 5th rock layer (a main roof), the 8th rock layer above it will also break with a lag. Furthermore, the total thickness of the main roof and its loading layers is 15.8 m, which includes the 5th, 6th and 7th rock layers.

Comparison of working resistance for different widths of mining face

Calculation of working resistance of hydraulic support based on thin plate theory

Based on the thin plate theory calculation and analysis, it can be concluded that the total height of the trapezoidal spatial structure above Panel 1305(\(\sum\limits_{{i=5}}^{7} {{h_{bri}}}\)) = 15.8 m, and the vertical uniform load subjected by the 5th rock layer (\({q_5}\)) = 434.3 kPa. Furthermore, the working resistance of any hydraulic support can be further calculated as follows28,29.

where G is the compression arch coefficient of hinged roof structure above the Panel 1305, with a value of 0.29; \({m_{RC}}\) is the roughness coefficient of the fracture surface of the immediate roof strata above the Panel 1305, with a value of 20; \({m_{CS}}\) is the effective uniaxial compressive strength of crack walls in the immediate roof strata above the Panel 1305, with a value of 79.3 MPa; \({\varphi _m}\) is the critical friction angle on the fracture surface of the immediate roof strata above the Panel 1305, with a value of 35°; \({\alpha _m}\) is the fracture angle of the immediate roof strata above the Panel 1305, with a value of 60°; \({\gamma _{a - i}}\) is the average bulk density of the immediate roof strata above the Panel 1305, with a value of 27.6 kN/m3.

Based on Eq. (29) and considering a dynamic load safety coefficient of 1.1, and knowing that the center distance between two adjacent hydraulic supports is about 1.5 m, therefore, the corresponding working resistance of each hydraulic support can be calculated and determined to be 4738.9 kN. The two-leg shield hydraulic support (Type ZY5500/24/52) can be selected and applied in the mining face of Panel 1305, thus achieving better maintenance of the stability of the roof above Panel 1305.

Calculation of working resistance of hydraulic support based on conventional key layer theory

Based on the conventional key layer theory calculation and analysis, the total height of the trapezoidal spatial structure above Panel 1305 (\(\sum\limits_{{i=5}}^{8} {{h_{bri}}}\)) = 21.2 m, and the vertical average load imposed by the 5th rock layer (\({q_5}\)) is 580.7 kPa at this moment, and the corresponding ultimate fracture length of the 5th rock layer (\({({l_m})_5}\)) decreases to 38.5 m. Furthermore, the working resistance of any hydraulic support can be further calculated as follows.

Based on Eq. (30) and considering a dynamic load safety coefficient of 1.1, and knowing that the center distance between two adjacent hydraulic supports is about 1.5 m, the corresponding working resistance of each hydraulic support is calculated to be 7.63 MN. The working resistance of the hydraulic support should be at least 7.63 MN to control the stability of the roof above Panel 1305. However, in actual on-site application, the hydraulic support with a rated working resistance of 5500 kN can achieve better control effect on the roof above Panel 1305. Obviously, the conventional key layer theory is not suitable in this case.

Influence of different widths of mining face on the height of trapezoidal Spatial structure

Considering that the mining face width of Panel 1305 is 85 m, the 9th rock layer (a stable inferior key strata) will never break during the mining process of Panel 1305. If the 9th rock layer (a stable inferior key strata) is to be broken, the mining face width of Panel 1305 should be appropriately widened, which can be calculated according to:

Equation (31) demonstrates that for the 9th rock layer (a stable inferior key strata) to break, the minimum value of the mining face width of Panel 1305 must be greater than or equal to 88.9 m. When the mining face width of Panel 1305 is in the [88.9 m, 116.7 m) interval, the 9th rock layer will be in a fractured form of vertical “O-X” structure, and when the mining face width of Panel 1305 is greater than 116.7 m, the 9th rock layer will transform into a fractured form of horizontal “O-X” structure.

Similarly, if the 12th rock layer (a stable inferior key strata) is to be broken, the mining face width of Panel 1305 should be further widened, which can be calculated according to the following formula.

According to Eq. (32), the 12th rock layer (a stable inferior key strata) will break only when the minimum value of the mining face width of Panel 1305 is ≥ 120.5 m. When the mining face width of Panel 1305 is in the [120.5 m, 122.6 m) interval, the 12th rock layer will be in a fractured form of vertical “O-X” structure, and when the mining face width of Panel 1305 is greater than 122.6 m, the 12th rock layer will transform into a fractured form of horizontal “O-X” structure.

Based on the above analysis, the mining face width of Panel 1305 will affect the fracture level of the rock layers in the overlying strata, further leading to changes in the height of trapezoidal spatial structure. Meanwhile, the changes in the mining face width of Panel 1305 will cause changes in the fractured form of any rock layer in the trapezoidal spatial structure. As the mining face width increases, any rock layer that previously experienced a fractured form of vertical “O-X” structure will also transform into a fractured form of horizontal “O-X” structure. In summary, the changes in the mining face width will lead to changes in the height of trapezoidal spatial structure, further resulting in synchronous changes in the working resistance of the hydraulic support within the mining face. Therefore, when there is a change in the mining face width, it is necessary to timely verify whether the working resistance of the originally selected hydraulic support meets the requirements.

Comparison of engineering practice

The on-site mine pressure monitoring data during the mining period of the Panel 1305 is shown in Fig. 12.

As shown in Fig. 12, the on-site mine pressure observation results indicate that: before the periodic roof weighting of Panel 1305, the mine pressure caused by the overlying strata above Panel 1305 to these hydraulic supports in the mining face is relatively small. The average working resistance of all these hydraulic supports is about 2405.1 kN, accounting for 43.7% of the rated working resistance value (5500 kN). The maximum working resistance value among all these hydraulic supports is about 2992.8 kN, accounting for 54.4% of the rated working resistance value; after the periodic roof weighting of Panel 1305, the mine pressure behavior is not severe, and the area with relatively large working resistance values is mainly concentrated in the middle of the mining face. The average working resistance of all these hydraulic supports is about 3395.5 kN, accounting for 61.7% of the rated working resistance value. The maximum working resistance value among all these hydraulic supports is about 5199.0 kN, accounting for 94.5% of the rated working resistance value. Due to the fact that the dynamic load coefficient of these hydraulic supports in the mining face can be determined by the ratio of the working resistance value after the periodic roof weighting and to the working resistance value before the periodic roof weighting, the calculation result shows that the dynamic load coefficient of these hydraulic supports in the mining face is within the range of 1.14–1.75, with an average of 1.40. It can be seen that the theoretical selection of hydraulic supports for Panel 1305 can meet the maintenance of the stability of the roof, and the utilization rate of the rated working resistance of these hydraulic supports is relatively high. In addition, it should be noted that due to sensitivity issue with the safety valves of these hydraulic supports, and even the failure of the safety valves of these hydraulic supports, when the working resistance of any hydraulic support reaches its rated value, the safety valve may not be able to open in time, resulting in individual hydraulic supports measuring working resistance value exceeding their rated value.

The distance between the Panel 1302 and the Panel 1305 is relatively close and the surrounding rock conditions of them are similar. But the mining face width of Panel 1302 is about 180 m, and the Panel 1302 also adopts the long-wall, large-height, full-height mining method. The four-leg shield hydraulic support (Type ZF7800/17/35) is selected and applied in the mining face of Panel 1302, with a rated working resistance of 7800 kN. The time-weighted mean resistance monitored by the hydraulic supports (Type ZF7800/17/35) in the mining face of Panel 1302 and the hydraulic supports (Type ZY5500/24/52) in the mining face of Panel 1305 are shown in Fig. 13.

As shown in Fig. 13, the maximum value and mean value of time-weighted mean resistance monitored by the hydraulic supports in the mining face of Panel 1305 is 4873.6 kN and 3625.1 kN respectively, accounting for 88.6% and 65.9% of the rated working resistance value (5500 kN), respectively. The time-weighted mean resistance of all these hydraulic supports in the mining face of Panel 1305 is less than 5500 kN, which means that these hydraulic supports (Type ZY5500/24/52) can the maintenance of the stability of the roof, and the utilization rate of the rated working resistance of these hydraulic supports is relatively high; it can be seen that the maximum value and mean value of time-weighted mean resistance monitored by the hydraulic supports in the mining face of Panel 1302 is 6812.7 kN and 5398.0 kN respectively, accounting for 87.3% and 69.2% of the rated working resistance value (7800 kN), respectively. About 50% of these hydraulic supports in the mining face of Panel 1302 have a time-weighted mean resistance greater than 5500 kN, but the time-weighted mean resistance of all these hydraulic supports in the mining face of Panel 1302 is less than 7800 kN, which means that these hydraulic supports (Type ZF7800/17/35) can the maintenance of the stability of the roof, and the utilization rate of the rated working resistance of these hydraulic supports is relatively high.

It also can be seen that under similar surrounding rock conditions, as the width of a mining face increases, the corresponding mine pressure strength of this mining face also increases significantly. As the width of a mining face increases from 85 m to 180 m, the corresponding maximum of time-weighted mean resistance monitored by the hydraulic supports in the mining face increases from 4873.6 kN to 6812.7 kN, with a growth rate of 39.8%; the corresponding mean of time-weighted mean resistance monitored by the hydraulic supports in the mining face increases from 3625.1 kN to 5398.0 kN, with a growth rate of 48.9%; the corresponding rated working resistance value of all these hydraulic supports in the mining face increases from 5500 kN to 7800 kN, with a growth rate of 41.8%.

Based on the above analysis, it can be concluded that when the width of a mining face is large, the corresponding height of trapezoidal spatial structure in the overlying rock strata increases, which in turn lead to a significant increase in the rated working resistance value of all these hydraulic supports in the mining face. Therefore, selecting hydraulic supports with higher rated working resistance can better control mine roof; however, when the width of a mining face is small, the corresponding height of trapezoidal spatial structure in the overlying rock strata decreases, which in turn lead to a significant reduction in the rated working resistance value of all these hydraulic supports in the mining face. Therefore, selecting hydraulic supports with lower rated working resistance can better control mine roof.

Conclusions

-

1.

The overlying rock strata above mine goaf fractures and caves into this gob, while considering that any rock layer in the overlying rock strata has its own fracture angle, then a trapezoidal spatial structure will be formed in the overlying rock strata based on the Winkler’s elastic foundation hypothesis and physical similarity simulation experiment results. Meanwhile, the smaller the difference in lithology of any rock layer in the overlying rock layer, the more regular the trapezoidal spatial structure formed by the fracture and collapse of overlying rock strata is.

-

2.

The relevant parameters of a trapezoidal spatial structure about overlying rock strata before and after periodic roof weighting can be theoretically calculated. The results indicate that the height of trapezoidal spatial structure is directly affected by the width of mining face, and the fractured form of rock layers changes from a horizontal “O-X” structure to a vertical “O-X” structure from the bottom up. When the upper surface width of the trapezoidal spatial structure is less than the limit breaking span, the fractured height of the overlying rock strata will not increase.

-

3.

Based on the Kirchhoff hypothesis, it is known that the width of a working face will affect the surface size of the trapezoidal spatial structure, thereby affecting the fracture characteristics of the overlying rock. The width of a working face is relatively large, the corresponding fractured height of overlying rock is also higher, and the total thickness of the loading layers is also larger.

-

4.

Based on the engineering practice carried out at the Panels 1302 and 1305 of Zhaozhuang No.2 underground mine, it can be seen that the changes in the mining face width will lead to changes in the height of trapezoidal spatial structure, further resulting in synchronous changes in the working resistance of the hydraulic support within the mining face. Therefore, when there is a change in the mining face width, it is necessary to timely verify whether the working resistance of the originally selected hydraulic support meets the requirements.

Data availability

All data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article, and there are not any restrictions on data access.

References

Li, Z. L. et al. Roadway stagger layout for effective control of gob-side rock bursts in the longwall mining of a thick coal seam. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 49 (2), 621–629 (2016).

Song, X. M., Gu, T. F. & Yan, Z. H. Effects of increasing working face’slength on underground pressure behaviors of mining super-high faces under shallow coal seam. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 26 (S2), 4007–4012 (2007).

Sun, Y. J. et al. Micro-seismic monitoring on fractured zone and water inrush mechanism analysis of deep mining above aquifer in Xingdong coalmine. Rock. Soil. Mech. 38 (8), 2335–2342 (2017).

Ju, J. F. & Xu, J. L. Structural characteristics of key strata and strata behavior of a fully mechanized Longwall face with 7.0 m height chocks. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. 58 (1), 46–54 (2013).

Qian, M. G. & Xu, J. L. Study on the O shape circle distribution characteristics of mining induced fractures in the overlaying strata. J. China Coal Soc. 23 (5), 466–469 (1998).

Liu, Z. G. et al. Study on coal seam roof gas drainage from the strike of annular fracture areas by the long drill method. Eng. Sci. 6 (5), 32–38 (2004).

Jiang, F. X. Viewpoint of Spatial structures of overlying strata and its application in coalmine. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 23 (1), 30–33 (2006).

Yang, K. & Xie, G. X. Caving thickness effects on distribution and evolution characteristics of mining induced fracture. J. China Coal Soc. 33 (10), 1092–1096 (2008).

Jiang, F. X. et al. Discussion on overlying strata spatial structures of longwall in coal mine. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 25 (5), 979–984 (2006).

Ma, Q. H. Study of the Overlying Strata O Letter Type Spatial Structures of Longwall and Correlate Rock Pressure (Shandong University of Science and Technology, 2005).

Dou, L. M. & He, H. Study of OX-F-T Spatial structure evolution of overlying strata in coal mines. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 31 (3), 453–460 (2012).

Gong, P. L. Study on Around Rock Control Theory and its Applications to Great Height Mining Faces (Taiyuan University of Technology, 2005).

Li, S. G., Shi, P. W. & Qian, M. G. Study on feature of ellipse distribution of dynamic rupturing zone within overlying strata in Longwall coal mining. Ground Press. Strata Contr. Z1, 44–46 (1999).

Liu, C. et al. Effect of mining face length on the evolution of spatial structure of overlying strata and the law of underground pressure in large mining height face. Rock. Soil. Mech. 39 (2), 691–698 (2018).

Arefi, M. & Bidgoli, E. M. R. Electro-elastic displacement and stress analysis of the piezoelectric doubly curved shells resting on Winkler’s foundation subjected to applied voltage. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct.. 26 (23), 1981–1994 (2024).

Qian, M. G., Shi, P. W. & Xu, J. L. Ground Pressure and Strata Control (China University of Mining and Technology, 2010).

Yang, Z. Q., Liu, C., Tang, S. C., Dou, L. M. & Cao, J. L. Rock burst mechanism analysis in an advanced segment of gob-side entry under different dip angles of the seam and prevention technology. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol.. 28 (6), 891–899 (2018).

Cai, W. et al. A fuzzy comprehensive evaluation methodology for rock burst forecasting using microseismic monitoring. Tunn. Undergr. Sp Tech. 80, 30–45 (2018).

Cao, W. Z., Shi, J. Q., Si, G. Y., Durucan, S. & Korre, A. Numerical modelling of microseismicity associated with Longwall coal mining. Int. J. Coal Geol. 193, 232–245 (2018).

Li, J. Z., Zhang, M., Li, Y. & Hu, H. Surrounding rock control mechanism in the gob-side retaining entry in thin coal seams, and its application. J. S. Afr. I Min. Metall. 118 (5), 471–480 (2018).

Wu, F. et al. Breaking features of loading key strata based on deep beam structure in shallow coal seam and its limited span-to-depth ratio. Bulg. Chem. Commun. 49, 89–95 (2017).

Guo, W. B., Zhao, G. B., Bai, E. H., Guo, M. J. & Wang, Y. Effect of overburden bending deformation and alluvium mechanical parameters on surface subsidence due to Longwall mining. B Eng. Geol. Environ. 80 (3), 2751–2764 (2021).

Guo, W. B., Zhao, G. B. & Bai, E. H. Critical failure of overlying rock strata and its criteria induced by high-intensity longwall mining. J. China Coal Soc. 45 (11), 3657–3666 (2020).

Liu, C. et al. Mechanism and control technology of supports crushing induced by main roof’s breaking ahead of workface when crossing abandoned roadway. J. China Coal Soc. 42 (8), 1932–1940 (2017).

Jia, X. R. Rock Mechanics and Rock Strata Control (China University of Mining and Technology, 2010).

Yi, K., Gong, P. L. & Liu, C. Overlying strata structures and roof control of working face under thin topsoil and thin bedrock in shallow seam. J. China Coal Soc. 43 (5), 1230–1237 (2018).

Zhu, G. A. et al. Mining-induced stress changes and rock burst control in a variable-thickness coal seam. Arab. J. Geosci. 5 (9), 365–376 (2016).

Bakun-Mazor, D., Hatzor, Y. H. & Dershowitz, W. S. Modeling mechanical layering effects on stability of underground openings in jointed sedimentary rocks. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. 46 (2), 262–271 (2009).

Yang, D. F., Zhang, L. F., Chai, M., Li, B. & Bai, Y. F. Study of roof breaking law of fully mechanized top coal caving mining in ultra-thick coal seam based on fracture mechanics. Rock. Soil. Mech. 37 (7), 2033–2039 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M732969), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China project (52104091).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Z.Y. carried out the theoretical research and numerical simulation studies, participated in the drafted the manuscript. Dr. Z.Z. carried out the modeling and solving of numerical simulation. Dr. M.H.E.N. participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. Dr. C.L. conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Z., Zheng, Z., El Naggar, M.H. et al. Study on the fracture characteristics of overlying rock strata under different mining face widths. Sci Rep 15, 11298 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91349-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91349-6