Abstract

Adjustable resonant peaks are necessary for high-precision photonic devices in biosensing, filtering, and optical communication. In this study, we focus on dual-ribbon two-dimensional gold gratings with varying periods and examine the Rayleigh conditions for different grating periods in detail to understand the excitation of resonance wavelengths. We demonstrate adjustable resonance behavior in an asymmetric dual-ribbon gold grating with periods ranging from 400 to 600 nm. The structure consists of subwavelength gold ribbons on a molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) monolayer, supported by a silica substrate. At visible resonant wavelengths, analysis of the field distributions reveals surface plasmon (SP) excitation, accompanied by the transformation of propagating diffraction orders into evanescent waves. When the resonant peak occurs at the wavelength where the transmission diffraction order vanishes, SPs are excited at the MoS2-gold ribbon interface and within the transmission domain. In contrast, by vanishing the reflection diffraction orders, SPs are excited at the gold ribbon-air interface and in the reflection domain. Understanding SP excitation wavelengths highlights the potential of these gratings for tunable nanoscale photonic devices. Their precise resonance control and simple fabrication make them suitable for scalable optical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metallic nanostructures, with their ability to localize light through localized surface plasmons (LSPs) and surface plasmons (SPs), are widely utilized in designing photonic devices1,2,3. In the case of LSPs, incident light excites collective oscillations of free electrons, forming a multipolar resonance confined to the nanostructure’s surface. This creates a strongly localized evanescent field tightly bound near the metal-dielectric interface4,5. SPs, on the other hand, are generated by coupling incident light, with an increased wave vector, to the free electrons in the metal. This interaction produces evanescent fields that propagate along and remain bound to the metal-dielectric interface4. To achieve the necessary wave vector enhancement for SP excitation, external evanescent waves are introduced, often through coupling with a prism or by structuring the metal film as a periodic grating6,7. The use of periodic gratings is accompanied by the excitation of diffraction orders.

By studying diffraction gratings in 1902, R.W. Wood reported an anomaly in the reflected light dips and peaks. This phenomenon, known as the Wood anomaly, occurs when certain wavelengths and incident angles meet conditions that cause abrupt intensity changes in the reflected light8. The first explanation of this anomaly was provided by L. Rayleigh in 1907, showing that the anomaly occurs when a diffraction order transfers from propagating to evanescent states9. When the incident light’s wavelength and angle of incidence satisfy this condition, one diffraction order stops propagating away from the grating and instead becomes evanescent, meaning it remains bound to the surface. This shift results in abrupt changes in the intensity of the reflected or transmitted light, producing the distinctive dips and peaks observed by Wood10.

The wavelength and angle of incidence at which a diffraction order transition occurs are strongly influenced by the grating structure’s geometry and dimensions11,12,13. For instance, a smaller grating period provides higher wave vector components at shorter wavelengths14. The Wood anomaly enables sharp optical responses at specific wavelengths and angles, making it valuable in designing filters, sensors, and sensing applications like surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy and biosensing15,16. It enhances sensitivity by concentrating light at the surface and is also used in telecommunications for precise wavelength filtering, supporting highly responsive and tunable optical devices17,18,19.

Recent studies have demonstrated that introducing structural perturbations in periodic gratings, such as period doubling, significantly alters their photonic behavior. This effect, known as Brillouin zone folding, allows previously inaccessible modes to become excitable under free-space illumination. Such folded modes exhibit enhanced robustness against structural disorder and provide precise control over resonance linewidths, as observed in photonic crystal systems20,21,22. However, despite these demonstrated advantages in dielectric photonic crystals, such phenomena remain underexplored in plasmonic systems.

In this study, we investigate dual-ribbon two-dimensional gold gratings with varying periods and analyze the Rayleigh diffraction conditions to understand the excitation mechanisms of resonance wavelengths. The studied grating consists of subwavelength gold ribbons placed on a monolayer of molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), supported by a silica (SiO2) substrate. A MoS2 monolayer is a single layer of MoS2 atoms, where each molybdenum atom is sandwiched between two sulfur atoms, forming a two-dimensional crystal structure. In its monolayer form, MoS2 exhibits a direct bandgap, making it particularly useful for optoelectronic and photonic applications due to its efficient light-matter interactions23,24,25,26. By focusing on asymmetric grating designs with periods ranging from \(400~\textrm{nm}\) to \(600~\textrm{nm}\), we examine the interplay between grating geometry and the Rayleigh conditions. Our results highlight how propagating diffraction orders transform into evanescent waves that excite SPPs at the interfaces, providing insights into designing highly tunable plasmonic devices.

Diffraction in a grating

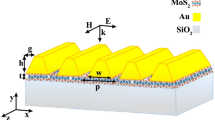

In Fig.1, a schematic of the unit cell of a grating that consists of gold (Au) ribbons on an atomically thin MoS2 layer is shown. The structure is extended on a silica glass substrate and the incident light illuminates it with the incident angle of \(\theta _i\). The incident light is diffracted from the grating to be partly reflected, \(r_0\), and partly refracted as the dashed red line into the MoS2. This refracted light is partly transmitted into the substrate, \(t_0\), and partly reflected back to MoS2. This reflected light, partly transmits to the air, \(r_1\), and partly reflects back into the MoS2 itself.

Schematic of the studied grating with Au ribbons on silica substrate that the MoS2 monolayer is inserted between them. In the unit cell of the grating, there are two ribbons with different widths (\(W_1\) and \(W_2\)) that are separated by different spacings (\(S_1\) and \(S_2\)). The height of both ribbons is equal and is denoted by h.

This procedure would be continued as the incoming light traps in the intermediate MoS2 layer and this trapped wave has the chance to transmit or reflect. Interference of the partially reflected waves into the air side that are indicated by complex reflection amplitude coefficients (\(r_0\), \(r_1\), \(r_2\), ...) makes the total reflection (\(R_{total}\)) of the structure. In this context, the squared absolute value of each reflection coefficient, \(|r_n|^{2}\), is known as the reflection of that nth order, \(R_{n}\). The \(R_{total}\) is constructed by calculating the squared absolute value of summation of all existing reflection coefficients as \(|r_0+r_1+r_2+...|^{2}\). All introduced notations have their equivalent in the transmission part: the squared absolute value of each complex transmission coefficient amplitude are \(t_0\), \(t_1\), \(t_2\), ..., transmittance of the nth transmission order is \(T_{n}=|t_n|^{2}\), and the total transmission (\(T_{total}\)) of the structure is calculated as \(|t_0+t_1+t_2+...|^{2}\). Constructive interference of partially reflected/ transmitted lights causes a peak in \(R_{total}\)/ \(T_{total}\) which is known as Bragg resonance.

Each reflection diffraction order is diffracted to an angle of \({\alpha _m}_r\) in which \(m_r\) denotes the reflection diffraction order and is an integer number that can take the values of \(\{...,-2,-1,0,1,2,...\}\). The condition for the constructive interference of the successive reflected diffracted orders is presented in equation 127:

In this equation, P is the period of the grating, \(n_{air}\) is the refractive index of air, and \(\lambda\) is the incident light wavelength. From equation 1, wavelength of the mth reflection diffraction order is obtained at normal illumination (\(\theta _i=0\)) as:

with \(n_{air}=1\). In equation 2, when the reflected ray travels along the interface, \({\alpha _m}_r=90^{\circ }\), the critical reflection diffraction wavelength, \({\lambda _r}_c,_ m\), is defined as \({\lambda _r}_c,_ m=|\frac{P}{m_r}|\). For \(\lambda \le {\lambda _r}_c,_ m\) in equation 2, \(\mid \sin {{\alpha _m}_r}\mid \le 1\) that is the necessary condition for propagation of the diffraction order. While, with \(\lambda > {\lambda _r}_c,_ m\), \(\mid \sin {{\alpha _m}_r}\mid\) would be greater than one, which mathematically is forbidden and leads to a nonpropagating (evanescent) diffraction order. This way, in a specific wavelength range, the allowed propagating and evanescent diffraction orders can be classified as equation 3:

In this equation \(\left\lfloor \right\rfloor\) sign floors the value of the decimal number. From equation 3, it can be seen that in the propagation range with \(\lambda \le {\lambda _r}_c,_ m\), the maximum diffraction order in the reflection spectrum is \(\left\lfloor \frac{P}{\lambda } \right\rfloor\). It is also worth mentioning that, in the case of \(m_r=0\), \({\lambda _r}_c,_ m=|\frac{P}{m_r}|=\infty\) and every \(\lambda\) would be less than \({\lambda _r}_c,_ m\). As a result, according to equation 3, \(m_r=0\) would be a propagating order throughout all wavelengths.

In the transmitted light, constructive interference occurs at the Bragg resonances that are formulated with equation 4 as:

In which, \(n_{sub}\) is the refractive index of the substrate and \({\alpha _m}_t\) is the angle of mth transmission diffraction order relative to the interface’s normal. The only difference between equation 1 and equation 4 is the medium of light propagation that is air in case of reflection and the substrate for the transmitted light. From equation 4, wavelength of the mth transmission diffraction order at normal illumination (\(\theta _i=0\)) is obtained as:

Similar to the case of reflection, if we consider \({\alpha _m}_t=90^{\circ }\) in equation 5, the critical transmission diffraction wavelength \({\lambda _t}_c,_ m=|\frac{n_{sub} P}{m_r}|\) is defined. Then, the allowed propagating and evanescent \(m_t\) orders are classified as equation 6:

Similar to the zero order of reflection diffraction, in the case of \(m_t=0\), \({\lambda _t}_c, _ m=\infty\) and every \(\lambda\) would be less than it. This way, according to equation 6, \(m_t=0\) is a propagating order throughout all wavelengths.

In the following, we will discuss the excited resonance modes in a grating with dual ribbons in one unit cell of it according to the excitation of different diffraction orders in the structure.

Grating structure

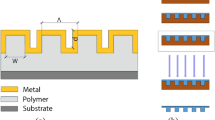

Our studied grating structure that is consists of dual Au ribbons that are separated by different spacing values of \(S_1\) and \(S_2\) in one period, is shown in Fig. 2.

The two ribbons have the same height of h but different widths of \(W_1\) and \(W_2\). The Au ribbons are arranged on MoS2 monolayer and the whole structure is placed on silica (SiO2) substrate. The incident light illuminates the structure normally with its magnetic field normal to the incident plane (TM-polarization). Complex refractive index of MoS2 and gold are taken from28 and29, respectively. The constant refractive index of SiO2 with \(n_{{\hbox {SiO}}_{2}}=1.45\) is from30. The Floquet periodic boundary condition is applied to the terminating zy-planes of the unit cell, with a period P. To accurately simulate the sub-nanometer thickness of MoS2 (0.615 nm) and avoid mesh-related challenges, it is modeled as a transition boundary. Throughout the paper, the height of the ribbons, \(h=100\) nm is taken as a constant, and \(S_1\) is considered to be equal to \(S_2\).

(a) Reflection spectrum (\(R_{total}\)) of the structure with \(P=400\) nm, \(S_1= S_2= 100\) nm, and different values of \(W_1\) and \(W_2\). As a reference, the reflection spectrum of a fully symmetric structure with \(W_1=W_2=100\) nm is inserted with the black solid line as a reference. The red oval shape that is marked as 1 is illustrative for the reflection peak at \(\lambda =580\) nm. (b) \(R_0\), \(R_{\pm 1}\), and \(R_{total}\) and \(T_0\), \(T_{\pm 1}\), and \(T_{total}\) for the structure with \(W_1=W_2=100\) nm. (c)/ (d) \(R_{total}\), \(R_0\), and \(R_{\pm 1}\)/ \(T_{total}\), \(T_0\), and \(T_{\pm 1}\) spectrum of the structure with \(W_1=160\) nm and \(W_2=40\) nm.

Results and discussion

In the current study, we selected visible spectrum with the wavelength range of \(\lambda _{min}=400\) nm to \(\lambda _{max}=800\) nm. Within this wavelength range, according to equation 3, for having at least one nonzero reflection diffraction order in the \(R_{total}\) the period P needs to be at least equal to the \(\lambda _{min}\) that is 400 nm. This way, we start our investigation from the period of \(P=400\) nm and increase it to \(P=700\) nm.

It has worth mentioning that, if we select \(P=300\) nm, according to the equation 3, \(m_{r_{max}}=\left\lfloor \frac{P}{\lambda _{min}} \right\rfloor =\left\lfloor \frac{300}{400} \right\rfloor =0\) and no reflection diffraction order higher than \(m_r=0\) contributes in \(R_{total}\). By increasing P to 400 nm, \(m_{r_{max}}\) reaches \(\left\lfloor \frac{P}{\lambda _{min}} \right\rfloor =\left\lfloor \frac{400}{400} \right\rfloor =1\) (equation 3). Besides this nonzero reflection diffraction order, according to the equation 6, \(m_{t_{max}}\) becomes \(\left\lfloor \frac{(n_{sub} \times P)}{\lambda _{min}} \right\rfloor =\left\lfloor \frac{(1.45 \times 400)}{400} \right\rfloor =1\). This way, the diffraction orders that are present in the reflection and transmission spectrum of the grating with \(P=400\) nm are \(m_r= -1, 0, 1\) and \(m_t= -1, 0, 1\) with the wavelengths of \({\lambda _r}_{c,_ \pm 1}=400\) nm that is right at the starting limit of our studied spectrum and \({\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 1}=580\) nm (equation 2 and equation 5). In case of \(P=500\) nm, \(m_{r_{max}}=\left\lfloor \frac{500}{400} \right\rfloor =1\) and \(m_{t_{max}}=\left\lfloor \frac{(1.45 \times 500)}{400} \right\rfloor =1\) then the diffraction orders that are within the studied wavelength range are \(m_r= -1, 0, 1\) and \(m_t= -1, 0, 1\) with wavelengths \({\lambda _r}_{c,_ \pm 1}=500\) nm and \({\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 1}=725\) nm. With \(P=600\) nm, \(m_{r_{max}}=\left\lfloor \frac{600}{400} \right\rfloor =1\) and \(m_{t_{max}}=\left\lfloor \frac{(1.45 \times 600)}{400} \right\rfloor =2\). This way, the diffraction orders are increased to \(m_r= -1, 0, 1\) and \(m_t= -2, -1, 0, 1, 2\) with wavelengths \({\lambda _r}_{c,_ \pm 1}=600\) nm, \({\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 2}=435\) nm, and \({\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 1}=870\) nm. From these wavelengths, \({\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 1}=870\) nm is out of the wavelength range that we focused on. If we consider \(P=700\) nm, \(m_{r_{max}}=\left\lfloor \frac{700}{400} \right\rfloor =1\) and \(m_{t_{max}}=\left\lfloor \frac{(1.45 \times 700)}{400} \right\rfloor =2\) with the diffraction orders \(m_r= -1, 0, 1\) and \(m_t= -2, -1, 0, 1, 2\) and related wavelengths of \({\lambda _r}_{c,_ \pm 1}=700\) nm, \({\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 2}=507.5\) nm, and \({\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 1}=1015\) nm that is not in our studied range.

This way, due to the studied wavelength range that we selected, \(\lambda _{min}=400\) nm to \(\lambda _{max}=800\) nm, we limit our study from \(p=400\) nm to \(P=600\) nm. We discuss the physics behind the peaks that appeared in the reflection spectrum of these structures by studying the reflection and transmission of all diffraction orders and their field distribution at their peak wavelengths.

Gratings with P=400 nm

In Fig. 3a we start investigating the reflection spectrum (\(R_{total}\)) of the structure with \(P=400\) nm, \(S_1= S_2=100\) nm, and unequal Au ribbon widths. As a reference, the reflection spectrum of the fully symmetric structure with identical ribbon widths, \(W_1= W_2=100\) nm, is also included as a black solid line. Compared to this symmetric structure, in the reflection spectrum of asymmetric gratings with \(W_1 \ne W_2\) at the wavelength of 580 nm emergence of a tiny peak can be recognized that is specified in the figure by red oval and marked as 1. The wavelength of appearance of this peak coincides with \({\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 1}= 580\) nm (equation 5). In Fig. 3b, \(R_0\), \(R_{\pm 1}\), \(R_{total}\), \(T_0\), \(T_{\pm 1}\), and \(T_{total}\) of the symmetric structure with \(W_1= W_2=100\) nm are plotted. It can be seen that only \(R_0\) and \(T_0\) are nonzero and make the \(R_{total}\) and \(T_{total}\).

For the asymmetric structure with \(W_1=140\) nm and \(W_2=60\) nm in Fig. 3c and d, \(R_0\), \(R_{\pm 1}\), and \(R_{total}\) and \(T_0\), \(T_{\pm 1}\), and \(T_{total}\) are plotted, respectively. In the reflection spectrum of Fig. 3c, it is apparent that \(R_{total}\) coincides completely with \(R_0\). While, in the transmission spectrum of Fig. 3d, deviation of \(T_{total}\) from the \(T_0\) occurs within the wavelength range of \(\lambda < {\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 1}\) (580 nm). In this wavelength range, \(T_{\pm 1}\) are nonzero values that drop to zero from the wavelength of \({\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 1}\) onwards. This nonzero to zero transition of \(T_{\pm 1}\) that occurs at the wavelength of \({\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 1}\) is a sign of propagating to non-propagating (evanescent) wave transfer of \(T_{\pm 1}\).

As we started our investigation wavelength range from 400 nm, at the wavelength of \({\lambda _r}_{c,_ \pm 1}=400\) nm we couldn’t recognize the role of reflection orders. Then, we increase the period of the structure to \(P=500\) nm and report the resulting reflection spectrum of asymmetric gratings with \(P=500\) nm in the next section.

(a) Reflection spectrum (\(R_{total}\)) of the structure with \(P=500\) nm, \(S_1= S_2= 170\) nm, and different values of \(W_1\) and \(W_2\). As a reference, the reflection spectrum of a fully symmetric structure with \(W_1=W_2=80\) nm is inserted with a black solid line. The two red oval shapes marked as 1 and 2 are illustrative for the reflection peaks at \(\lambda =500\) nm and \(\lambda =725\) nm, respectively. (b) \(R_0\), \(R_{\pm 1}\), and \(R_{total}\) and \(T_0\), \(T_{\pm 1}\), and \(T_{total}\) for the structure with \(W_1=W_2=80\) nm. (c)/ (d) \(R_{total}\), \(R_0\), and \(R_{\pm 1}\)/ \(T_{total}\), \(T_0\), and \(T_{\pm 1}\) spectrum of the structure with \(W_1=140\) nm and \(W_2=20\) nm.

Gratings with P=500 nm

For \(P=500\) nm, as we discussed, \(m_{r_{max}}=1\) and \(m_{t_{max}}=1\) and relative diffraction order wavelengths are \({\lambda _r}_{c,_ \pm 1}=500\) nm and \({\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 1}=725\) nm (equation 2 and equation 5). In Fig. 4a reflection spectrum of the gratings with \(P=500\) nm that have the geometrical parameters of \(W_1 \ne W_2\) and \(S_1 = S_2=170\) nm are included. As a reference, the reflection spectrum of a fully symmetric grating with \(W_1=W_2=80\) nm is also included with a solid black line. Comparing the reflection spectrum of the asymmetric gratings (\(W_1\ne W_2\)) with that of the fully symmetric one (\(W_1=W_2=80\) nm) reveals excitation of two resonant peaks at \(\lambda =500\) nm and \(\lambda =725\) nm (marked by red ovals 1 and 2 in Fig. 4a) in the reflection spectrum of the asymmetric gratings. To have a better insight into the role of diffraction order’s excitation, in Fig. 4b the \(R_0\), \(R_{\pm 1}\), \(R_{total}\), \(T_0\), \(T_{\pm 1}\), and \(T_{total}\) spectrum of the fully symmetric structure with \(W_1=W_2=80\) nm is included. It can be seen that other than \(R_0\) and \(T_0\) that are fully matched with \(R_{total}\) and \(T_{total}\), other diffraction orders are zero. While, in case of the grating with \(W_1=140\) nm and \(W_2=20\) nm, looking at the \(R_{total}\), \(R_0\) and \(R_{\pm 1}\) in Fig. 4c, shows the deviation of \(R_{total}\) from \(R_0\) for the wavelengths less than \({\lambda _r}_{c,_ \pm 1}=500\) nm that is marked as 1. The difference between \(R_0\) and \(R_{total}\) for \(\lambda <{\lambda _r}_{c,_ \pm 1}\) is compensated by nonzero \(R_{\pm 1}\). The same phenomena happen in case of light transmission in Fig. 4d in which \(T_0\), \(T_{\pm 1}\), and \(T_{total}\) spectrum are included and for the wavelengths longer than \({\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 1}=725\) nm, that is marked as 2, the only nonzero diffraction order is \(T_0\). For \(\lambda <{\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 1}\), sum of the \(T_0\) and \(T_{\pm 1}\) results in the total transmission, \(T_{total}\).

This way, the \(R_{\pm 1}\) diffraction orders are nonzero within the wavelength range of \(\lambda <{\lambda _r}_{c,_ \pm 1}=500\) nm and the \(T_{\pm 1}\) are other than zero in the range of \(\lambda <{\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 1}=725\) nm. Beyond these wavelength limits, the \(R_{\pm 1}\) and the \(T_{\pm 1}\) turn into zero abruptly that is a sign of transferring from a propagating wave to an evanescent wave.

To have a deeper insight of what is happening at the wavelengths of \({\lambda _r}_{c,_ \pm 1}\) and \({\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 1}\), in Fig. 5, the \(H_z\) distribution of the fully symmetric structure with \(W_1=W_2=80\) nm and the asymmetric structure with \(W_1=140\) nm, and \(W_2=20\) nm are included at the wavelengths of \(\lambda _1=500\) nm and \(\lambda _2=725\) nm. As it can be seen, in the case of symmetric structure not at the wavelength of \(\lambda _1=500\) nm, Fig. 5a, nor at \(\lambda _2=725\) nm, Fig. 5b, any special change in the illuminating plane wave distribution can be recognized. While, in the asymmetric structure, at the wavelength of \(\lambda _{1}=500\) nm, Fig. 5c, excitation of special mode can be recognized in the air side. A mode that is related to the excitation of SPs at the top of the gold ribbons. With the excitation of SPs, the incident light switches from a propagating to an evanescent wave that is confined to the interface of the gold ribbons and air. This change from propagating to evanescent in the reflection domain, causes an abrupt switch of the \(R_{\pm 1}\) to zero at the wavelength of \(\lambda _1={\lambda _r}_{c,_ \pm 1}=500\), as it was discussed in describing Fig. 4c.

At the wavelength of \(\lambda _{2}=725\) nm, Fig. 5d, without any significant change, the plane wave illumination can be recognized in the reflection domain. While in the substrate excitation of SPs at the interface of gold ribbons, and MoS2 layer is apparent. In this case, excitation of SPs in the transmission domain is along with abrupt \(T_{\pm 1}\) switch to zero at the wavelength of \(\lambda _2={\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 1}=725\) nm (Fig. 4d).

Gratings with P=600 nm

In Fig. 6a, in the structure with \(P=600\) nm and \(S_1 = S_2=170\) nm like the cases of \(P=400\) nm and \(P=500\) nm in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4, we explore the role of diffraction orders of the asymmetric structures with different values of \(W_1\) and \(W_2\) on their reflection spectrum. As a reference, the reflection spectrum of the asymmetric structure with \(P=600\) nm, \(S_1 = S_2=170\) nm, and \(W_1=W_2=130\) nm is included in Fig. 6a with solid black line. The two red oval lines that are included in Fig. 6a show the wavelengths of \(\lambda _1={\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 2}=435\) nm and \(\lambda _2={\lambda _r}_{c,_ \pm 1}=600\) nm. As we discussed earlier, \({\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 1}\) reaches 870 nm which is out of our studied wavelength range.

(a) Reflection spectrum (\(R_{total}\)) of the structure with \(P=600\) nm, \(S_1= S_2= 170\) nm, and different values of \(W_1\) and \(W_2\). As a reference, the reflection spectrum of a fully symmetric structure with \(W_1=W_2=130\) nm is inserted with a black solid line. (b) \(R_0\), \(R_{\pm 1}\), and \(R_{total}\) and \(T_0\), \(T_{\pm 1}\), and \(T_{total}\) for the symmetric structure with \(W_1=W_2=130\) nm. (c)/ (d) \(R_{total}\), \(R_0\), and \(R_{\pm 1}\)/ \(T_{total}\), \(T_0\), and \(T_{\pm 1}\) spectrum of the structure with \(W_1=170\) nm and \(W_2=90\) nm.

In Fig. 6b, \(R_0\), \(R_{\pm 1}\), \(R_{\pm 2}\), \(R_{total}\), \(T_0\), \(T_{\pm 1}\), \(T_{\pm 2}\), and \(T_{total}\) spectrum of the fully symmetric structure with \(W_1=W_2=130\) nm is included. As it can be seen, \(T_{total}\) of this structure deviates from \(T_0\) at the wavelength range of \(\lambda <{\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 2}=435\) nm and beyond this range, they coincide completely. With reminding \({\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 2}=435\) nm, at the wavelength range of \(\lambda <{\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 2}\) the nonzero diffraction orders of \(T_{\pm 2}\) compensate the deviation of \(T_{total}\) and \(T_{0}\). The solid green and dashed purple lines in Fig. 6b that are illustrative for \(T_2\) and \(T_{-2}\) show the nonzero value of these diffraction orders in the wavelength range of \(\lambda <435\) nm. These diffraction orders turn to zero at the wavelength of 435 nm, a sign of their coupling to evanescent waves from this wavelength onwards. In this symmetric structure, \(R_0\) coincides exactly with \(R_{total}\) that shows no reflection diffraction order plays any role in the observed reflection spectrum.

From the presented spectrum of the asymmetric structures in Fig. 6a, we select the one with \(W_1=170\) nm and \(W_2=90\) nm for further studies. In Fig. 6c, the \(R_0\), \(R_{\pm 1}\), \(R_{\pm 2}\), and \(R_{total}\) spectrum and in Fig. 6d, the \(T_0\), \(T_{\pm 1}\), \(T_{\pm 2}\), and \(T_{total}\) spectrum of this asymmetric structure is presented. In Fig. 6c, at the wavelength of \(\lambda =600\) nm, the marked peak as 2 is in the reflection spectrum of \(R_{total}\). At the wavelength range \(\lambda <600\) nm, deviation of \(R_{total}\) from \(R_{0}\) can be seen that is along with nonzero \(R_{\pm 1}\) at this wavelength range. Which is expected as in the structure with \(P=600\) nm \({\lambda _r}_{c,_ \pm 1}\) is 600 nm and the same as cases with \(P=400\) nm and \(P=500\) nm, at the wavelength range \(\lambda <{\lambda _r}_{c,_ \pm 1}\) nonzero \(R_{\pm 1}\) compensate the \(R_{total}\) and \(R_{0}\) deviation. \(R_{total}\) and \(R_{0}\) difference ends for the wavelengths greater than \({\lambda _r}_{c,_ \pm 1}\) that happens along with zero \(R_{\pm 1}\) diffraction orders that are changed to non-propagating waves beyond \({\lambda _r}_{c,_ \pm 1}=600\) nm.

In Fig. 6d, like the case of Fig. 6b for the symmetric structure with \(P=600\) nm, nonzero \(T_{\pm 2}\) at the wavelength range \(\lambda <{\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 2}=435\) nm is the reason of \(T_{total}\) and \(T_0\) deviation. To explore the physics behind vanishing the diffraction orders of \(T_{\pm 2}\) and \(R_{\pm 1}\) at \(\lambda _{1}=435\) nm and \(\lambda _{2}=600\) nm, in Fig. 7, the \(H_z\) field distributions of the symmetric and asymmetric structures with \(P=600\) nm are included.

\(H_z\) field distribution of the symmetric structure with \(P=600\) nm, \(S_1 = S_2=170\) nm, and \(W_1=W_2=130\) nm at (a) \(\lambda _1=435\) nm and (b) \(\lambda _2=600\) nm. In asymmetric structure with \(P=600\) nm, \(S_1 = S_2=170\) nm, and \(W_1=170\) nm and \(W_2=90\) nm, the \(H_z\) field distribution is shown at (c) \(\lambda _{1}=435\) nm and (d) \(\lambda _{2}=600\) nm.

In Fig. 7a/c and b/d, the \(H_z\) field distribution of the symmetric/asymmetric grating with \(W_1=W_2=130\) nm/\(W_1=170\) nm and \(W_2=90\) nm at the wavelength of \(\lambda _1=435\) nm (\({\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 2}\)) and \(\lambda _2=600\) nm (\({\lambda _r}_{c,_ \pm 1}\)) are shown. As we discussed the reflection and transmission spectrum of the symmetric structure in Fig. 6b, the nonzero \(T_{\pm 2}\) at the wavelength range of \(\lambda <{\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 1}\) becomes zero at the wavelength of 435 nm. Figure 7a shows this nonzero to zero transfer of \(T_{\pm 2}\) at the wavelength of 435 nm by coupling the incoming light to the SPs in the transmission domain at the interface of gold ribbons and MoS2 monolayer. At the wavelength of 600 nm, no special coupling to the SPs at the reflection domain can be recognized in Fig. 7b. This is the reason for the perfect match of \(R_0\) and \(R_{total}\) in the reflection spectrum of Fig. 6b in all studied wavelength ranges.

In the case of the asymmetric structure, as shown in Fig. 6c and d, at \({\lambda _r}_{c,_ \pm 1}=600\) nm and \({\lambda _t}_{c,_ \pm 2}=435\) nm, abrupt change of \(R_{\pm 2}\) and \(T_{\pm 2}\) to zero occurs. By investigating the \(H_z\) field distribution at \(\lambda _1=435\) nm in Fig. 7c, coupling of the incident light to the excited SPs at the interface of gold ribbons and MoS2 layer that is the transmission domain is apparent. At the wavelength of \(\lambda =600\) nm that is the wavelength of \({\lambda _r}_{c,_ \pm 1}\), with an abrupt change of \(R_{\pm 1}\) to zero at this wavelength, the propagating incident light couples to the SPs on the gold ribbons and air interface in the reflection domain.

conclusion

In this study, we have demonstrated the adjustability of resonant peaks in asymmetric dual-ribbon gold gratings with different periods. By carefully examining Rayleigh conditions for various grating periods, we have shown that dual-ribbon gratings with periods ranging from 400 nm to 600 nm can achieve resonance wavelengths within the visible spectrum. Our findings show that the peaks in the reflection spectrum occur at the wavelengths where one of the diffraction orders (either reflection or transmission) becomes zero and transitions from propagating to evanescent waves. Specifically, if the resonant peak occurs at the wavelength where the transmission diffraction order vanishes, SPs are excited at the MoS2-gold ribbon interface and in the transmission domain. Conversely, if the resonant peak occurs at the wavelength where the reflection diffraction order vanishes, SPs are excited at the gold ribbon-air interface and in the reflection domain. The ability to control SP excitation at specific wavelengths and manage these transitions from propagating to evanescent diffraction orders opens up new possibilities for developing highly efficient optical components, such as biosensors, optical filters, and wavelength-selective elements. In structures that support both discrete and continuum states, within structures with other types of perturbations (other than ribbons with different widths), or by the inclusion of various materials’ refractive index, the interaction between these states can influence peak positions by introducing newly created modes contributions beyond those dictated by Rayleigh conditions. Our results pave the way for further exploration and optimization of grating structures for a broad range of photonic applications, where precise control of resonance wavelengths is essential for enhanced functionality.

Data availability

The data underlying the results presented in this paper are not publicly available but can be obtained from the author, M. Hashemi, upon request.

References

Shi, H. et al. Plasmonic metal nanostructures with extremely small features: new effects, fabrication and applications. Nanoscale Adv. 3, 4349–4369 (2021).

Dahan, K. A., Li, Y., Xu, J. & Kan, C. Recent progress of gold nanostructures and their applications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25, 18545–18576 (2023).

Wu, J. Z., Ghopry, S. A., Liu, B. & Shultz, A. Metallic and non-metallic plasmonic nanostructures for lspr sensors. Micromachines 14, 1393 (2023).

Maier, S. Plasmonics: Fundamentals and applications (2007).

Shen, Y., Chen, N., Dong, G. & Hu, S. Manipulating multipole resonances in spoof localized surface plasmons for wideband filtering. Opt. Lett. 46, 1550–1553 (2021).

Murugan, D. et al. Recent advances in grating coupled surface plasmon resonance technology. Adv. Opt. Mater. 12(34), 2401862 (2024).

Aftab, M., Mansha, M. S., Iqbal, T. & Farooq, M. Surface plasmon excitation: theory, configurations, and applications. Plasmonics 19, 1701–1719 (2024).

Wood, R. W. Xlii. on a remarkable case of uneven distribution of light in a diffraction grating spectrum. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philos. Magazine J. Sci. 4, 396–402 (1902).

Rayleigh, L. On the dynamical theory of gratings. Proc. Royal Soc. London Series A, Contain. Papers Math. Phys. Character 79, 399–416 (1907).

Rayleigh, L. Iii. note on the remarkable case of diffraction spectra described by prof. wood. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philos. Magazine J. Sci. 14, 60–65 (1907).

Murugan, D. et al. Recent advances in grating coupled surface plasmon resonance technology. Adv. Opt. Mater. 12(34), 2401862 (2024).

Tavakoli, M., Jalili, Y. S. & Elahi, S. M. Rayleigh-wood anomaly approximation with fdtd simulation of plasmonic gold nanohole array for determination of optimum extraordinary optical transmission characteristics. Superlatt. Microstruct. 130, 454–471 (2019).

Darweesh, A. A., Bauman, S. J., Debu, D. T. & Herzog, J. B. The role of rayleigh-wood anomalies and surface plasmons in optical enhancement for nano-gratings. Nanomaterials 8, 809 (2018).

Minopoli, A., Acunzo, A., Della Ventura, B. & Velotta, R. Nanostructured surfaces as plasmonic biosensors: A review. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 9, 2101133 (2022).

Karaca Acari, I. et al. A plasmonic biosensor pre-diagnostic tool for familial mediterranean fever. Nat. Commun. 15, 8515 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Ultra-high sensitivity photonic crystal fiber sensor based on dispersion turning point sensitization of surface plasmonic polariton modes for low ri liquid detection. Opt. Exp. 32, 32895–32908 (2024).

Yang, L., Liu, H., Cai, B., Wu, L. & Cheng, Y. Miniaturized broadband high out-of-band rejection bandpass filter based on spoof surface plasmon polaritons with defected ground structure. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 26722 (2024).

Carvalho, F. & Mejia-Salazar, J. R. Plasmonics for telecommunications applications. Sensors 20(9), 2488 (2020).

Alkorbi, A. S. et al. Design and analysis of a graphene/gold nanostructure metasurface surface plasmon resonance sensor for biomedical applications. Plasmonics https://doi.org/10.1007/s11468-024-02576-y (2024).

Overvig, A. C., Shrestha, S. & Yu, N. Dimerized high contrast gratings. Nanophotonics 7, 1157–1168 (2018).

Overvig, A. C., Malek, S. C., Carter, M. J., Shrestha, S. & Yu, N. Selection rules for quasibound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. B 102, 035434 (2020).

Wang, W., Srivastava, Y. K., Tan, T. C., Wang, Z. & Singh, R. Brillouin zone folding driven bound states in the continuum. Nat. Commun. 14, 2811 (2023).

Hashemi, M., Ansari, N. & Vazayefi, M. Absorption peak wavelength and bandwidth control in mos 2-based absorbers on the basis of spps and lsps excitation. Opt. Mater. Exp. 13, 850–861 (2023).

Janisch, C. et al. Mos2 monolayers on nanocavities: enhancement in light–matter interaction. 2D Mater. 3, 025017 (2016).

Sattari, F. & Mirershadi, S. Enhanced light absorption in a mos2-based photonic crystal. Phys. B 666, 415093 (2023).

Hashemi, M., Ansari, N. & Vazayefi, M. Mos2-based absorbers with whole visible spectrum coverage and high efficiency. Sci. Rep. 12, 6313 (2022).

John, R., Milford, F. J., Christy, R. W., Kunde, S. & Hermiston, S. Found. Electromagn. Theory (Pearson, 1967).

Ansari, N. & Ghorbani, F. Light absorption optimization in two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide van der waals heterostructures. JOSA B 35, 1179–1185 (2018).

Johnson, P. B. & Christy, R.-W. Optical constants of the noble metals. Phys. Rev. B 6, 4370 (1972).

Ghosh, G. Dispersion-equation coefficients for the refractive index and birefringence of calcite and quartz crystals. Opt. Commun. 163, 95–102 (1999).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mahdieh Hashemi wrote the manuscript and supervised the simulations. Zohreh Keshavarz did the simulations. Maryam Moradi analyzed the results and discussed the physics behind the scattering from the gratings. Narges Ansari supervised the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hashemi, M., Keshavarz, Z., Moradi, M. et al. Dual-ribbon grating resonance modes: a survey based on diffraction orders. Sci Rep 15, 6706 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91494-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91494-y