Abstract

Pediatric nurses are exposed to occupational stress due to the demanding care of sick children and complex interactions with families. The negative impact on nurse’s physical and mental health, stress can also affect the quality of care. On the other hand, work engagement as a positive mental state and psychological capital as one of the supporting factors can help improve conditions and reduce occupational stress. However, the role of psychological capital in the relationship between occupational stress and work engagement in pediatric nurses needs further research. The aim of this study was to determine the mediating role of psychological capital in the relationship between work engagement and occupational stress in nurses working on pediatric wards. The present study was a predictive correlational study using the path analysis model. The statistical population of this study consisted of 251 pediatric nurses. The sampling was conducted from December 2023 to May 2024. Data collection instruments included the Demographic Profile Form, Chen’s occupational Stress Questionnaire, Schaufeli et al.'s Work Engagement Questionnaire, and Luthans’ Psychological Capital Questionnaire. The data analysis was carried out using the SPSS 26 and AMOS 24 software. The results of this study showed that there was an inverse and significant relationship between work engagement and occupational stress in nurses working in the pediatric ward (p < 0.001, β = −0.22). In addition, a positive and significant relationship was observed between work engagement and psychological capital among nurses (p < 0.001, β = 0.39). The results also showed that there was an inverse and significant relationship between psychological capital and occupational stress (p < 0.001, β = −0.23). The results of the final model represented psychological capital as a mediating variable that explains the relationship between work engagement and occupational stress of nurses. The results of this study showed that higher work engagement leads to a reduction in occupational stress in nurses working in the pediatric ward and that psychological capital acts as a mediating variable in this relationship. Nurses who have higher work engagement and psychological capital, experience less occupational stress. Age and work experience were also related to reduced stress and increased work engagement and psychological capital. It is suggested that hospital managers focus on educational and supportive programs to enhance psychological capital and increase the work engagement of nurses working in pediatric wards to improve the quality of care for children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Occupational stress is the response of workers who are confronted with work demands and workloads that do not match their knowledge and skills and challenge their ability to cope1. Nursing is often considered as a stressful profession due to factors related to the work environment and the different demands of the profession2. Pediatric nurses are the most affected by stress compared to those working in other hospital wards3,4,5. The reason for the high stress of pediatric nurses is the challenge of communicating with the different people in the child’s family and the complications at work related to the variability of children’s needs according to their developmental stage6. Pediatric nurses are often at risk for suffering from compassion, as they are regularly confronted with the traumatic aspects of a child’s illness or death, injury, or medical treatment, and families’ emotional reactions to their child’s illness can lead to numerous negative outcomes such as burnout7. Compassion satisfaction can also lead to ineffective or deficient patient care, callousness and indifference toward patients and co-workers, medical errors, poor patient outcomes and low patient satisfaction8,9. Occupational stress among pediatric nurses can affect their performance. Safety in pediatric inpatient care and quality of pediatric care are critical outcomes of nursing care10.

Work engagement is a positive, satisfying and work-related state of mind characterized by dedication, vigor, and absorption11. The concept of work engagement is based on the ability of employees to express their cognitive, physical and emotional well-being in the performance of their tasks12. The performance of pediatric nurses can have a major impact on the experiences that children will have in the hospital in the future. Nursing care of children is challenging because caring for different age groups (from infants to adolescents) requires professional management at different developmental stages of motor, physical, emotional, and cognitive development13. Accordingly, pediatric nurses should be skilled in dealing with sick children and adopt a caring attitude towards their families14. To increase nurses’ commitment to the care of children and their families, we should consider possible interventions in this direction.15. The importance of conducting further research on work engagement in nursing is strongly emphasized. As an important determinant of people’s mental health and positive organizational behavior, work engagement has attracted the attention of various fields including education, business, nursing and medical services16,17. It is necessary to investigate the work engagement of pediatric nurses and its influential factors. However, most studies conducted on work engagement do not focus on pediatric nurses11.

Occupational stress in nurses may be the result of a combination of factors related to the work environment and personal factors18; demographic characteristics such as age; marital status and education19; work situations, e.g. working hours , work shifts, patient behavior20; work roles such as workload, personal responsibilities, role conflicts21; and personal resources such as social support and coping methods22 as well as psychological characteristics23 of the individual.

Literature review

The relationship between occupational stress and work engagement has been investigated in several texts1,24,25 and in nursing10,11,26. The studies conducted related to these variables in the pediatric department also confirmed the importance of nurses caring behaviors and stated that working in this department in particular is associated with more occupational stress6. At the same time, it must be said that no study has measured the mediating effect of psychological capital with occupational stress and work engagement in the form of a model.

Some researchers believe that work engagement not only helps to reduce perceived job stress, rather, it leads to organizational and financial success by increasing employee engagement and organizational commitment27. Excessive stress at work leads to poor performance, such as decreased ability to make sound decisions, poor concentration, decreased job performance, decreased initiative, decreased interest in work, increased difficulty in thinking, responsibility, and decreased efficiency and productivity28,29. Employees are emotionally and cognitively motivated when they know what is expected of them. The amount of occupational stress a nurse experiences plays a key role in their emotional and cognitive availability at work30. The literature on stress generally shows a negative relationship between occupational stress and employee engagement31. Therefore, there is a theoretical relationship between job stress and work engagement32. Mostert and Rothmann’s study showed that work engagement is best predicted by conscientiousness, emotional stability, and low stress due to work demands33.

Mediating effect of psychological capital on the relationship between work engagement and occupational stress

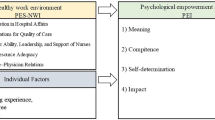

To improve management and nursing performance, it is very important to identify mediating factors that neutralize the negative effects of the variables that influence nurses’ work performance. One variable could be psychological capital34. Psychological capital is an individual psychological resource related to having (1) confidence (self-efficacy), (2) a positive view of present and future success (optimism), (3) continuously pursuing a goal and, if necessary, changing the path to the goal to achieve success (hope), and (4) maintaining composure, bouncing back, and even surpassing success in the face of difficulty and adversity (resilience)35. According to Luthans et al. , psychological capital is about developing and changing oneself to become the best person and considered a state that can be developed and changed36. The psychological capital of nurses is meant to protect them from the stressors of work. Therefore, the role of psychological capital as a mediator has attracted the attention of many researchers in various fields, including medical and educational sciences37,38,39

Theoretical framework and hypothesis development

In this study, the combination of Conservation of Resources (COR) theory and JD-R (Job Demands- Resources) provides a comprehensive theoretical framework for examining the influence of psychological capital on nurses’ job performance mediated by problem-focused coping and job engagement. COR theory provides a framework for how resources operate in individual and social systems40 and help to recognize the nature of stress as a universal phenomenon in any context related to people’s experience41

According to the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, people are motivated to protect and conserve their resources (conservation) and to acquire new resources (acquisition). This theory offers relevant insights because it assumes that the value of resources (e.g., passion for work) underlying effective behaviors (e.g., performance) is organizationally regulated42. Accordingly, employees develop different perceptions of how likely it is that a particular resource will promote goal attainment, depending on the value the organization places on such a resource. The signals sent by the organization play an important role in the employees’ decision to invest or not to invest in a particular resource (e.g., work engagement). These assumptions are particularly important for understanding the relationship between work motivation and performance. When resources are threatened or depleted, people experience stress and adopt a defensive posture to conserve remaining resources. When resources are threatened or depleted, individuals experience stress and adopt a defensive posture to conserve remaining resources. According to COR, individuals need to acquire and maintain resources regardless of whether the obstacle are facing is stressful or not. They use their most important personal resources to acquire new resources43. The study by Lockey et al. on the theory of conservation of resources, showed that stressors are related to declines in employee well-being such that there is a positive relationship with fatigue and a negative relationship with employee engagement44. Healthcare providers, especially nurses, are exposed to numerous occupational stressors that can negatively impact their physical and mental health and also decrease their work engagement. Work engagement can be considered the opposite of burnout, which is characterized by the exchange of energy and professional efficiency45. In light of this theory, it would be interesting to investigate the influence of work engagement on occupational stress. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H1. Pediatric nurses’ work engagement is negatively correlated with occupational stress

According to COR, psychological capital as an additional psychological resource could potentially reduce stress. There is a large body of literature that shows how the harmful effects of stressors can be mitigated by psychological capital46. Apart from the direct effects of occupational stress, and in line with Hobfoll et al. 's direction to integrate other theories to understand the effect of resources at the micro-level, Broaden and Build theory47 is used as an additional theoretical mechanism to understand how occupational stress might interact with psychological capital and lead to greater creativity. The theory states that individuals with positive psychological states (e.g. high psychological capital) can bounce back from negative events (e.g. high occupational stress) resulting in an employee reaching neutral activation level that allow them to pursue more behavioral options. With high psychological capital, occupational stress can potentially be turned into an opportunity for better performance48.

The results of previous studies show that occupational stress in nurses may be the result of a combination of factors related to the work environment and personal factors18. These factors include demographic characteristics such as age, marital status and education19; work situation, e.g. position, working hours, working shifts, patient behavior20; the professional career, e.g. workload, personal responsibility, role conflict21; and personal resources such as social support and coping methods22, as well as psychological characteristics23 of the individual. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H2. Pediatric nurses’ occupational stress is negatively correlated with psychological capital

Finally from the perspective of COR theory, we propose that pediatric nurses seek to acquire, protect and rebuild their valuable resources. COR theory is premised on the idea that individuals strive to gain, maintain, promote and secure certain resources that they consider centrally49,50. The JD-R model suggests that in the stress process, high work demand lead to negative work outcomes by increasing employees’ susceptibility to burnout. In contrast, certain work resources , e.g. psychological resources, lead to positive work outcomes by increasing employee work engagement51. The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model supports the argument that psychological capital predicts work engagement. They help people recover from “yesterday’s” difficulties and regain their motivation so that they can focus on, dedicate themselves to and engaged in their work52. As a personal resource, psychological capital can support work engagement. Psychological capital is the positive psychological state of an individual’s development that relies on the principles of positive psychology and positive organizational behavior, i.e., the self (self-efficacy), positive expectation of the future (optimism), the pursuit of goals, and, when possible, the redirection of the direction chosen for a particular goal (resilience)53. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H3. Pediatric nurses’ psychological capital plays a mediation role between Work engagements and occupational stress

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study in which a path analysis approach was used to determine the mediating effect of nurses’ psychological capital on the relationship between work engagements and occupational stress. This study was conducted from December 2023 to May 2024 in 6 hospitals affiliated with Iran University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran. The ethics committee of Iran University of medical sciences approved the research and confirmed that all research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations. A convenience sample of 251 pediatric nurses was recruited. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) they volunteered for the study and (b) they had been working in pediatric nursing for more than 6 months, (c) they did not suffer from mental illness and did not take psychotropic drugs according to self-report. Based on the study design, which included three latent variables and 62 observed variables, a minimum sample size of 251 pediatric nurses was calculated. This calculation assumed a significance level of less than 0.05, a power level of 0.8 and a small effect size of 0.25, as defined by Westland and Christopher54.

Measurements

The data for this study came from a four-part questionnaire. The demographic survey asked questions about age, gender, marital status, education level, number of children, type of employment, work experience (year), work experience in pediatric ward (year), interest in working in the pediatrics ward, shift work and organizational position. The other sections consisted of three scales, which are described in the following three sections.

The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES): Work engagement questionnaire was developed by Schaufeli et al.55 and involved 17-item with seven-point Likert scaling, and includes three dimensions: Vigor, Absorption and Dedication56. Participants answered the questions on a 7-point scale ranging from “0” (never) to “6” (every day or always). The possible range of values was between 0 and 102, with high values indicating a high levels of work engagement. Findings from factor analysis show that this scale has three different factors57, which supports the construct validity. In the present sample, the Cronbach’s alpha of the total scale was 0.94; 0.84 for the vigor, 0.89 for dedication, and 0.81 for absorption subscales. This instrument was psychometrically tested in Iran by Torabinia et al. The results showed that the face and content validity of the Persian version of the instrument was acceptable. The internal consistency reliability for the total scale and subscales was 0.76 to 0.8958.

Nurses’ Occupational Stress Scale: This questionnaire was developed by Chen et al. in 2013 and revised in 202059. This 21- item questionnaire has 9 subscales: Work demands, work-family conflict, and inadequate support from colleagues or caregivers, violence and bullying at work, organizational issues, and occupational hazards, difficulties taking leave, powerlessness, and unmet basic physiological needs. It is rated on a four-point Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 4 (completely agree). Final score ranges from 21 to 84, with a higher score indicating greater stress in workplace. The correlation coefficients of the subscales for test–retest reliability ranged from 0.71 to 0.83. The coefficients for internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) ranged from 0.35 to 0.77. This instrument was psychometrically tested in Iran by Safari Shirazi and colleagues. Cronbach’s alpha and Macdonald’s omega coefficients for the entire scale were α = 0.94 and ω = 0.95, respectively60.

Psychological Capital Questionnaire-24 (PCQ–24): Psychological capital questionnaire was developed by Luthans et al.61. This questionnaire contains 24 items with four dimensions of psychological capital that measure hope, optimism, self-efficacy and resilience. It is a 6-point rating scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6). The total score ranged from 24 to 144, with the higher the score, the higher the psychological capital. The validation study showed that the questionnaire had adequate validity and reliability. The Cronbach alpha ranged from 0.718 to 0.923. The Persian version of this instrument was psychometrically evaluated by Mohsenabadi et al. The internal consistency of the factors evaluated with the Cronbach’s alpha method was 0.8562.

In this study, the validity of the questionnaires was presented to 10 members of the review team and their corrective comments and suggestions were taken into account. The reliability of the questionnaires was also established by determining internal consistency. For example, the questionnaire was presented to 10 pediatric nurses and after completion the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated 0.90 for the Nurses’ occupational Stress Scale, 0.91 for The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale and 0.86 for the Psychological Capital Questionnaire.

After obtaining the approval of the ethics committee and the research in 6 hospitals, the researchers attended the pediatric departments in different shifts and selected the participants according to the inclusion criteria. Then the objectives of the study were explained to them and they were given written informed consent if they wanted to participate in the study. Then the questionnaire was distributed to the nurses. After completing the questionnaires, to ensure that they were filled out correctly, a review was conducted by the researcher. To avoid bias and sharing of opinions among the nurses, the sampling and completion of the questionnaires were conducted individually and separately.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Ethic Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (ethic code: IR.IUMS.REC.1402.679). The questionnaires were anonymous and self-reported. Each nurse was free to participate in the study, refuse to participate or withdraw at any time without any consequences. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Data analysis

SPSS version 26 and AMOS version 24 were used to analyze the data. First, general characteristics of participants were expressed in terms of frequencies and percentages. Means and standard deviations were calculated to determine the nurses’ level of occupational stress, work engagement and psychological capital. To analyze differences in the levels of occupational stress, work engagement and psychological capital based on the pediatric nurse’s general characteristics, a t-test or one-way analysis of variance were utilized. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to examine the relationships among occupational stress, work engagement and psychological capital.

Structural equation model was used to explore the mediating role of psychological capital between work engagement and occupational stress.

Results

Participant characteristics

According to the results, 11.6% of the participants were male and 88.4% were female. The average age was 30.63 ± 7.31 years, the average nursing experience was 6.78 ± 6.89 years, and the average nursing experience in pediatric ward was 4.70 ± 5.77 years. More than half of the nurses were single (55.8%), had a bachelor’s degree (84.5%), had no children (70.1%), and owned their own house (51.8%). Most pediatric nurses worked in rotation shifts (81.7), had a formal type of employment (35.1), and were interested in the pediatric ward (76.9) Table 1.

Work engagement, based on participants’ demographics

Among all pediatric nurses, the mean level of work engagement was 64.85 ± 18.84. The results showed that there were statistically significant differences in the level of work engagement among pediatric nurses with respect to their age, marital status, work experience and work experience on the pediatric ward (p = 0.000, p = 0.040, p = 0.007, p = 0.000, p = 0.012, respectively). Nurses who were 30–40 years old had a higher engagement at work (65.91 ± 16.17). Married nurses (67.93 ± 20.16) also showed a higher work engagement. In terms of work experience, nurses with 5–10 years of working experience as a nurses (69.95 ± 18.08) and nurses who worked in the pediatric ward (69.95 ± 18.36) had higher work engagement.

Occupational stress, based on participants’ demographics

The mean level of occupational stress among nurses was 64.85 ± 18.84. In this study, statistically significant differences were found in the level of occupational stress among pediatric nurses depending on their age their age and length of experience as a pediatric nurse (p = 0.021 and p = 0.015 respectively). Pediatric nurses aged < 30 years had a higher level of occupational stress (65.26 ± 9.75) compared to those in other age groups. There were statistically significant differences in the level of occupational stress for all years of professional experience, so that pediatric nurses with 5–10 years of work experience had a higher level of occupational stress (69.20 ± 17.37).

Psychological capital, based on participants’ demographics

The mean level of psychological capital was 98.29 ± 0.52. The level of psychological capital of nurses differed significantly by ages, marital status and length of experience as a nurse and pediatric nurse (p = 0.000, p = 0.017, p = 0.000 and p = 0.000 respectively). Nurses aged ≥ 40 years old had a higher level of psychological capital than nurses in other age group (107.83 ± 22.44 Vs 95.95 ± 13.50). Married nurses (108.25 ± 38.97) had higher psychological capital than unmarried or divorced nurses. Regarding the influence of work experience on psychological capital, pediatric nurses with more than 20 years’ of work experience as a nurse and as a pediatric nurse had higher levels of psychological capital (112.66 ± 27.76 and 118.62 ± 36.67, respectively) than those with less than 20 years of experience (Table 1).

Correlations among occupational stress, work engagement, and psychological capital

The results of a correlation analysis showed that work engagement and occupational stress had a statistically significant negative correlation (r = – 0.31, p < 0.001) and also a moderate correlation (with an effect size of 0.50). Work engagement and psychological capital showed a statistically significant, positive correlation (r = 0.39, p < 0.001), which was also a moderate correlation (with an effect size of 0.91). Occupational stress and psychological capital showed a statistically significant negative correlation (r = – 0.39, p < 0.001), which was also a moderate correlation (with an effect size of 0.96) (Table 2).

Mediating role of psychological capital in relationship between work engagement and occupational stress

The structural model included three latent constructs (psychological capital, work engagement and occupational stress) and 62 observed variables. The fit indices indicated that the model was appropriate: χ2/df = 3.23, TLI = 0.85, CFI = 0.87, IFI = 0.87, RFI = 0.87, NFI = 0.79, RMSEA = 0.06. Furthermore, all factor loads of indicators on latent constructs were significant (p < 0.05), indicating that all latent constructs were well represented by their indicators. As shown in Table 3, work engagement had a significant direct effect on psychological capital (β = 0.39, p = 0.001) and occupational stress (β = – 0.22, p = 0.001). The direct effect of psychological capital on occupational stress was – 0.23 (p = 0.001). The indirect effect of work engagement, psychological capital and occupational stress was 0.25 (p = 0.001), which suggested that psychological capital partially mediates between work engagement and occupational stress.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate the mediating role of psychological capital in the relationship between work engagement and work stress. In this study, the levels of work engagement reported by pediatric nurses were at the moderate level. In a study conducted by Khorin et al. in Iran and in the children ward, the results showed that the mean score for work engagement was at a moderate to a high level63. The study by Alharbi and Alrwaitey, also showed that the level of work engagement in pediatric nurses is moderate11.

Also, the present study showed that occupational stress is significantly related to work engagement. This finding concurs with the results of study by Terry, Nielson, and Pritchard (1993) that found that high levels of stress were associated with low levels of occupational satisfaction (representing the enjoyment component of work-related well-being)64. Occupational stress has a negative relationship with occupational satisfaction. Visser et al. (2003) stated that occupational satisfaction has a protective effect against the negative consequences of occupational stress. When stress is high and satisfaction is low, the risk of low energy—one of the main aspects of low work engagement—increases significantly65. Work engagement is a dynamic process that, although it is stable over time, can change under the influence of working conditions, and when it is recognized negatively, it can be seen that it can harm people’s mental health66. In line with this study, Cardioli et al.'s study showed that job stress has a negative relationship with engagement. The study also stated that since engagement is directly related to work performance, stimulating individual and collective engagement can reduce occupational stress and increase the participation of professionals at work, provide the well-being of teams, and improve the quality of services provided1.

According to the literature, engagement is a phenomenon that is related to the group that the worker belongs to and is influenced by individual, organizational and work-specific characteristics67,68. This study evidences these affirmations when it finds differences between the levels of engagement according to sociodemographic and professional characteristics, such as their age, marital status, work experience and work experience in the pediatric ward. Nurses who were 30–40 years old had a higher engagement at work. Married nurses also showed a higher work engagement. In terms of work experience, nurses with 5–10 years of work experience as a nurses and nurses who worked in the pediatric ward had higher work engagement. In line with the present study, Alharbi and Alrwaitey’s study showed that a higher UWES-9S score was associated with older age. Younger nurses have been shown to have low work engagement levels69. According to career development theory, it can be argued that workers under the age of 25 are in the exploratory stage of their career development and need more experience to move forward to reach maturity, which increases with age70. Also older nurses have more work experience and more stable family relationships, leading to higher work engagement levels71.

The pediatric nurses in this study reported levels of occupational stress at high level and similar to those reported in a previous study conducted72,73. In line with the present study, Zhou et al.'s study showed that nurses working in the pediatric ward have a high level of occupational stress74. These results may be related to the work conditions that pediatric nurses experience due to the specific nature of the service, heavy workload, work environment and complex interpersonal relationships, work and family conflicts74. Pediatric nurses are the major force in hospitals and are in the front line in contact with ill children and their parents. Suspicion of child abuse and critically ill children are two topics that distinguish pediatric from other specialties and why this specialty can have high stress and emotional burden73.

Also, the present study showed that occupational stress and psychological capital showed a statistically significant negative correlation. In line with the present study, study by Kim and Kweon showed that job stress leads to a decrease in psychological capital. Consequently, the higher the psychological capital of the nurse, the lower the job stress and burnout75. When nurses endure heavy workloads in these stressful environments, it may lead to negative thinking, which in turn reduces psychological capital76. In Chang et al.'s study, the psychological capital PsyCap was significantly negatively associated with the symptoms of stress and job stress77. The study of Shalani et al. in Iran showed that psychological capital has an inverse and significant relationship with job stress, which means that the higher the psychological capital people have, the less job stress they experience78. The study stated that a busy career is stressful and this tension has affected their quality of life and health. In the meantime, psychological capital can play an important role in reducing the occupational stress of nurses by creating positive attitudes and views towards work, increasing hope, and having the necessary self-confidence to succeed in challenging tasks. Having psychological capital enables people to be less stressed and to have a clear view about themselves and to be less affected by daily events. Therefore, these people have higher psychological health and experience less job stress78.

On the other hand, the results of this study support previous research which states that there is a positive influence between psychological capitals on work engagement79. This means that when the psychological capital of the individual increases, the higher the work engagement the individual feels, and vice versa when the psychological capital decreases, the lower the work engagement will be. Work engagement is an aspect that includes positive emotions, full involvement in doing work and is characterized by three main dimensions, namely vigor, dedication, and absorption80

Our research also found that psychological capital partially mediated the relationship between pediatric nurse work engagement and occupational stress. Thus, increased nurse work engagement levels result in indirectly and directly lowered levels of psychological capital and increases in occupational stress. Therefore, one important result of this study is that because psychological capital plays a partial mediating role between work engagement and occupational stress, efforts must be made to increase psychological capital levels, specifically, occupational stress management programs to lower turnover intention. In line with the present study, the results of the study showed that psychological capital mediates the relationship between role stress and work engagement81. Based on job demands resource (JD-R) theory, psychological capital is a personal resource that people can use to promote work engagement during stress. Specifically, nurses with high psychological capital are optimistic about finding solutions and hope for the end when facing obstacles and problems at work. They can constantly motivate themselves to overcome problems, get out of difficulties quickly and devote more time and energy to their work82.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, all variables were evaluated using a self-report questionnaire, which carries the risk of bias and this normally leads to participants providing socially desirable responses, which may comprise the accuracy of the findings. Socially desirable responding is a common problem especially when self-report questionnaires are used. Secondly, the study was designed as a cross-sectional study. It therefore does not allow any clear causal conclusions to be drawn. Future studies should use a longitudinal design to test the causal model. One of the strengths of this study is that it was multicenter and the sample was conducted in 6 hospitals, which increases the generalizability of the results. In addition, the results of this study can be used as an extension of the model in the field of nursing, and this study has a particular theoretical guiding importance for the research direction of pediatric nursing and management in the future.

Conclusion

This study helps address several important gaps in the literature and provides a deeper understanding of the factors associated with occupational stress and work engagement in pediatric nurses. Also, the findings of the present study provide empirical evidence on the significant role of psychological capital and this is the first study to report the prevalence of psychological capital in a sample of pediatric nurses. The findings of this study add to the existing literature on psychological capital, occupational stress, and work engagement. Results revealed that psychological capital played a mediating role in the relationships between occupational stress, and work engagement. Therefore, it is essential that organizations invest in the development of psychological capital of their employees in order to take full advantage of it for employees and the organization. Because psychological capital is developable, we suggest that the hospital administration can evaluate the psychological capital of nurses and implement targeted intervention.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cordioli, D. F. C. et al. Occupational stress and engagement in primary health care workers. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 72, 1580–1587 (2019).

Woodhead, E. L., Northrop, L. & Edelstein, B. Stress, social support, and burnout among long-term care nursing staff. J. Appl. Gerontol. 35, 84–105 (2016).

Czaja, A. S., Moss, M. & Mealer, M. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder among pediatric acute care nurses. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 27, 357–365 (2012).

Callaghan, P., Tak-Ying, S. A. & Wyatt, P. A. Factors related to stress and coping among Chinese nurses in Hong Kong. J. Adv. Nurs. 31, 1518–1527 (2000).

Liao, H. et al. Stressors, coping styles, and anxiety & depression in pediatric nurses with different lengths of service in six tertiary hospitals in Chengdu, China. Transl. Pediatr. 9, 827 (2020).

Mosayebi, M., Rassouli, M. & Nasiri, M. Correlation of occupational stress with professional self-concept in pediatric nurses. J. Health Promot. Manage. 6, 23–29 (2018).

Robins, P. M., Meltzer, L. & Zelikovsky, N. The experience of secondary traumatic stress upon care providers working within a children’s hospital. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 24, 270–279 (2009).

Coetzee, S. K. & Klopper, H. C. Compassion fatigue within nursing practice: a concept analysis. Nurs. Health Sci. 12, 235–243 (2010).

Kutney-Lee, A. et al. Nursing: a key to patient satisfaction: patients’ reports of satisfaction are higher in hospitals where nurses practice in better work environments or with more favorable patient-to-nurse ratios. Health Aff. 28, w669–w677 (2009).

Mokhtar, K., El Shikieri, A. & Rayan, A. The relationship between occupational stressors and performance amongst nurses working in pediatric and intensive care units. Am. J. Nurs. Res. 4, 34–40 (2016).

Alharbi, M. F. & Alrwaitey, R. Z. Work engagement status of registered nurses in pediatric units in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 18, e0283213 (2023).

Berta, W. et al. Relationships between work outcomes, work attitudes and work environments of health support workers in Ontario long-term care and home and community care settings. Hum. Resour. Health 16, 1–11 (2018).

Yoo, S. Y. & Cho, H. Exploring the influences of nurses’ partnership with parents, attitude to families’ importance in nursing care, and professional self-efficacy on quality of pediatric nursing care: a path model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 5452 (2020).

García-Sierra, R., Fernández-Castro, J. & Martínez-Zaragoza, F. Engagement of nurses in their profession. Qualitative study on engagement. Enferm. Clín. (Engl. Ed.) 27, 153–162 (2017).

Buckley, L., Berta, W., Cleverley, K. & Widger, K. The relationships amongst pediatric nurses’ work environments, work attitudes, and experiences of burnout. Front. Pediatr. 9, 1536 (2021).

Wang, X., Liu, L., Zou, F., Hao, J. & Wu, H. Associations of occupational stressors, perceived organizational support, and psychological capital with work engagement among Chinese female nurses. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 56 (2017).

Tomic, M. & Tomic, E. Existential fulfilment, workload and work engagement among nurses. J. Res. Nurs. 16, 468–479 (2011).

Wu, H., Chi, T. S., Chen, L., Wang, L. & Jin, Y. P. Occupational stress among hospital nurses: cross-sectional survey. J. Adv. Nurs. 66, 627–634 (2010).

Kaur, M. & Kumar, R. Determinants of occupational stress among urban Indian school teachers. Res. Educ. 105, 3–17 (2019).

Inoue, M., Tsukano, K., Muraoka, M., Kaneko, F. & Okamura, H. Psychological impact of verbal abuse and violence by patients on nurses working in psychiatric departments. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 60, 29–36 (2006).

Anees, R. T., Heidler, P., Cavaliere, L. P. L. & Nordin, N. A. Brain drain in higher education. The impact of job stress and workload on turnover intention and the mediating role of job satisfaction at universities. Eur. J. Business Manage. Res. 6, 1–8 (2021).

Yousaf, S., Rasheed, M. I., Hameed, Z. & Luqman, A. Occupational stress and its outcomes: the role of work-social support in the hospitality industry. Person. Rev. 49, 755–773 (2020).

Suleman, Q., Hussain, I., Shehzad, S., Syed, M. A. & Raja, S. A. Relationship between perceived occupational stress and psychological well-being among secondary school heads in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. PloS one 13, e0208143 (2018).

Damayanti, H. & Mursid, A. Pengaruh occupational stress dan psychological contract terhadap work engagement Melalui psychological well being di Saat Pandemi Covid 19 (Studi pada Karyawan KCP Bank Jateng Pasar Johar). Magisma J. Ilmiah Ekon. Bisnis 9, 12–26 (2021).

Ernes, A. & Wanasida, A. S. The influence of occupational stress, anxiety, work engagement and perceived organizational support on innovation outputs at XYZ hospital during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Manaje. Kesehatan Indonesia 11, 319–336 (2023).

Van der Colff, J. J. & Rothmann, S. Occupational stress, sense of coherence, coping, burnout and work engagement of registered nurses in South Africa. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 35, 1–10 (2009).

Koyuncu, M., Burke, R. J. & Fiksenbaum, L. Work engagement among women managers and professionals in a Turkish bank: potential antecedents and consequences. Equal Opport. Int. 25, 299–310 (2006).

Noor, S. & Maad, N. Examining the relationship between work life conflict, stress and turnover intentions among marketing executives in Pakistan. Int. J. Business Manage. 3, 93–102 (2008).

De Lorenzo, M. S. Employee mental illness: moving towards a dominant discourse in management and HRM. Int. J. Business Manage. 9, 133 (2014).

Ongori, H. & Agolla, J. E. Occupational stress in organizations and its effects on organizational performance. J. Manage. Res. 8, 123–135 (2008).

Vta, S. A. Occupational stress and organizational commitment in private banks: a Sri Lankan experience. Eur. J. Business Manage. 5, 254–267 (2013).

Simon, N. & Amarakoon, U. A. Impact of occupational stress on employee engagement. In 12th International Conference on Business Management (ICBM) (2015).

Mostert, K. & Rothmann, S. Work-related well-being in the South African Police Service. J. Criminal Justice 34, 479–491 (2006).

Woo, C. H. & Kim, C. Impact of workplace incivility on compassion competence of Korean nurses: Moderating effect of psychological capital. J. Nurs. Manage. 28, 682–689 (2020).

Wang, M.-F. et al. The relationship between occupational stressors and insomnia in hospital nurses: the mediating role of psychological capital. Front. Psychol. 13, 1070809 (2023).

Luthans, K. W., Lebsack, S. A. & Lebsack, R. R. Positivity in healthcare: relation of optimism to performance. J. Health Organ. Manage. 22, 178–188 (2008).

Peng, S., Cheng, X. & Guo, J. The relationship between occupational stress and psychological capital and sleep quality in intensive care nurses. Ind. Hygiene Occup. Dis. 45, 121–124 (2019).

Khalid, A., Pan, F., Li, P., Wang, W. & Ghaffari, A. S. The impact of occupational stress on job burnout among bank employees in Pakistan, with psychological capital as a mediator. Front. Public Health 7, 410 (2020).

Shah, A., Munir, S. & Zaheer, M. Occupational stress and job burnout of female medical staff: The moderating role of psychological capital and social support. J. Manage. Res. 2021, 212–249 (2021).

Kim, H. S., Sherman, D. K. & Taylor, S. E. Culture and social support. Am. Psychol. 63, 518 (2008).

Hobfoll, S. E. & Lilly, R. S. Resource conservation as a strategy for community psychology. J. Commun. Psychol. 21, 128–148 (1993).

Hobfoll, S. E. Conservation of resources theory: its implication for stress, health, and resilience. Oxford Handb. Stress Health Coping 127, 147 (2011).

Bakker, A. B. & Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 22, 273 (2017).

Lockey, S. et al. The impact of workplace stressors on exhaustion and work engagement in policing. Police J. 95, 190–206 (2022).

Fiabane, E., Giorgi, I., Sguazzin, C. & Argentero, P. Work engagement and occupational stress in nurses and other healthcare workers: the role of organisational and personal factors. J. Clin. Nurs. 22, 2614–2624 (2013).

Avey, J. B., Luthans, F. & Jensen, S. M. Psychological capital: a positive resource for combating employee stress and turnover. Hum. Resourc. Manage. 48, 677–693 (2009).

Fredrickson, B. L. The broaden–and–build theory of positive emotions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B: Biol. Sci. 359, 1367–1377 (2004).

Crum, A. J., Salovey, P. & Achor, S. Rethinking stress: the role of mindsets in determining the stress response. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 104, 716 (2013).

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P. & Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 5, 103–128 (2018).

Moin, M. F., Wei, F., Khan, A. N., Ali, A. & Chang, S. C. Abusive supervision and job outcomes: a moderated mediation model. J. Organ. Change Manage. 35, 430–440 (2022).

Adil, A. & Kamal, A. Authentic leadership and psychological capital in job demands-resources model among Pakistani university teachers. Int. J. Leadership Educ. 23, 734–754 (2020).

Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P. & Taris, T. W. Work engagement: an emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work Stress 22, 187–200 (2008).

Luthans, F., Youssef, C. M. & Avolio, B. J. Psychological capital: Investing and developing positive organizational behavior. Positive Organ. Behav. 1, 9–24 (2007).

Westland, J. C. Lower bounds on sample size in structural equation modeling. Electron. Commerce Res. Appl. 9, 476–487 (2010).

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B. & Salanova, M. Utrecht work engagement scale-9. In Educational and Psychological Measurement (2003).

Schaufeli, W. B. & Bakker, A. B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: a multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 25, 293–315 (2004).

Seppälä, P. et al. The construct validity of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale: multisample and longitudinal evidence. J. Happiness Stud. 10, 459–481 (2009).

Torabinia, M., Mahmoudi, S., Dolatshahi, M. & Abyaz, M. R. Measuring engagement in nurses: the psychometric properties of the Persian version of Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Med. J. Islamic Republic of Iran 31, 15 (2017).

Chen, Y.-C. et al. Development of the nurses’ occupational stressor scale. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 649 (2020).

Safari Shirazi, M., Sadeghzadeh, M. & Abbasi, M. Psychometric properties of Persian version of condensed nurses’ occupational stress scale in Covid-19 pandemic period. Avicenna J. Nurs. Midwifery Care 29, 245–255 (2021).

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B. & Norman, S. M. Positive psychological capital: measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Person. Psychol. 60, 541–572 (2007).

Mohsenabadi, H., Fathi-Ashtiani, A. & Ahmadizadeh, M. J. Psychometric properties of the Persian Version of the Psychological Capital Questionnaire-24 (PCQ-24) in a military unit. J. Milit. Med. 23, 738–749 (2021).

Khorin, Z. S. M., Larijani, T. T., Rahimi, S. & Haghani, S. The association between caring behavior, self-efficacy, and work engagement among formal caregivers serving children with intellectual disability. Int. J. Med. Investig. 12, 1 (2023).

Terry, D. J., Nielsen, M. & Perchard, L. Effects of work stress on psychological well-being and job satisfaction: the stress-buffering role of social support. Austral. J. Psychol. 45, 168–175 (1993).

Rothmann, S. Job satisfaction, occupational stress, burnout and work engagement as components of work-related wellbeing. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 34, 11–16 (2008).

Magnan, E. D. S. et al. Normatização da versão brasileira da Escala Utrecht de engajamento no trabalho. Aval. Psicol. Int. J. Psychol. Assess. 15, 133–140 (2016).

Bhuvanaiah, T. & Raya, R. Predicting employee work engagement levels, determinants and performance outcome: empirical validation in the context of an information technology organization. Glob. Business Rev. 17, 934–951 (2016).

Setti, I. & Argentero, P. Organizational features of workplace and job engagement among Swiss healthcare workers. Nurs. Health Sci. 13, 425–432 (2011).

Yin, Y. et al. Subtypes of work engagement in frontline supporting nurses during COVID-19 pandemic: a latent profile analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 78, 4071–4081 (2022).

Super, D. E. The career development inventory. Br. J. Guid. Counsel. 1, 37–50 (1973).

Wang, Y., Gao, Y. & Xun, Y. Work engagement and associated factors among dental nurses in China. BMC Oral Health 21, 1–9 (2021).

Choi, H. et al. Relationship between job stress and compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, burnout for nurses in children’s hospital. Child Health Nurs. Res. 23, 459–469 (2017).

Choobineh, A., Museloo, B. K., Ghaem, H. & Daneshmandi, H. Investigating association between job stress dimensions and prevalence of low back pain among hospital nurses. Work 69, 307–314 (2021).

Zhou, Y., Guo, X. & Yin, H. A structural equation model of the relationship among occupational stress, coping styles, and mental health of pediatric nurses in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 22, 416 (2022).

Kim, S. & Kweon, Y. Psychological capital mediates the association between job stress and burnout of among Korean psychiatric nurses. In Healthcare 199 (MDPI, 2020).

Liu, Y., Aungsuroch, Y., Gunawan, J. & Zeng, D. Job stress, psychological capital, perceived social support, and occupational burnout among hospital nurses. J. Nurs Scholarship 53, 511–518 (2021).

Liu, L., Chang, Y., Fu, J., Wang, J. & Wang, L. The mediating role of psychological capital on the association between occupational stress and depressive symptoms among Chinese physicians: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 12, 1–8 (2012).

Shalani, B., Abbariki, A. & Sadeghi, S. Prediction of job stress based on psychological capital and job performance in nurses of Kermanshah Hospitals. Depict. Health 10, 280–286 (2019).

Schaufeli, W. Work engagement: what do we know. In International OHP Workshop Timisoara (2011).

Syam, R. & Arifin, N. A. I. The effect of psychological capital on work engagement of nurse at pertiwi hospital in Makassar City. J. Ilmiah Ilmu Administr. Publ. 11, 215–222 (2021).

Sun, X., Yin, H., Liu, C. & Zhao, F. Psychological capital and perceived supervisor social support as mediating roles between role stress and work engagement among Chinese clinical nursing teachers: a cross-sectional study. BMJ open 13, e073303 (2023).

Sheng, X., Wang, Y., Hong, W., Zhu, Z. & Zhang, X. The curvilinear relationship between daily time pressure and work engagement: the role of psychological capital and sleep. Int. J. Stress Manage. 26, 25 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all the pediatric nurses who participated in this study.

Funding

This study project was supported by Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, under Grant number (1402–4-3- 27674).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KKH: wrote the first draft of the manuscript, Data collection, MA: Conceptualized the study, Methodology supervisor, Developed an analytical framework, Manuscript writing, HP: Data collection supervisor, Interpreted the results, Manuscript editing, Data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests:

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Keykha, K.A., Alinejad-Naeini, M. & Peyrovi, H. The mediating role of psychological capital in the association between work engagement and occupational stress in pediatric nurses. Sci Rep 15, 7041 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91521-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91521-y