Abstract

Extended periods of inactivity in sports can impact athletes’ performance and overall well-being. The current study examined the effects of a 10-week wrestling -specific detraining period on the isokinetic strength of knee and shoulder flexor and extensor muscles, knee proprioception, and dynamic balance among young male elite wrestlers. This prospective study included 63 male wrestlers : age (19.33 ± 3 years), height (174.32 ± 6.8 cm), weight (80.21 ± 22.01 kg), BMI (25.34 ± 5.89), fat percentage (13.25 ± 5.80) in Tehran’s premier wrestling league. Baseline measurements, including isokinetic strength of knee and shoulder flexors and extensors, knee proprioception, and dynamic balance, were evaluated using the Biodex 4 dynamometer and Biodex balance meter, respectively, and repeated after a 10-week lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic at Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran. Statistical analysis utilized dependent t-tests to compare the results. Significant differences were observed in the isokinetic strength of shoulder and knee flexor and extensor muscles at angular speeds of 60, 180, and 300 degrees per second after 10 weeks of detraining (p < 0.05). Additionally, a decrease in the accuracy of knee joint proprioception was found, including active angle restoration at angles of 30°, 60°, and 90° and passive movement detection in flexion and extension at a 90-degree angle (p < 0.05). Moreover, dynamic balance significantly reduced in the single-leg form (p < 0.05). The findings revealed that wrestling -specific detraining period can significantly affect musculoskeletal and proprioceptive parameters in wrestlers, increasing the risk of injuries and reducing the performance and physical fitness. Consistent engagement in wrestling -specific training is essential to ensure optimal fitness and overall well-being, particularly for elite athletes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wrestling is considered one of the most challenging and physically intense combat sports requiring physical strength, technical skill, and strategic intuition1. It is demanded by high-intensity effort and appropriate training practices to enhance its performance and competitive edge2,combining with advanced tactical strategies, making it one of the most extensively studied disciplines among combat sports3. However, a wrestling-specific detraining period and limitations on the training regimes due to any disruption, including injury, illness, or other factors such as the COVID-19 epidemic, can have insightful negative effects on physical capabilities and athlete performance, posing challenges for coaches, athletes, and sports authorities4. Therefore, many considerations must be taken into account by sporting organizations, governing bodies, medical providers, athletes, and coaches when planning the return to training for athletes5. Of note, the focus should be on the progression of all aspects of training, including the status of individual athletes to be prepared appropriately concerning physical and psychological aspects6.

In addition, considering the association of internal injury risk factors in elite athletes can help developing targeted training programs and injury prevention strategies to optimize performance and minimize the risk of injuries7. In elite wrestling, athletes engage in high-intensity and physically demanding activities with a combination of strength, balance, and proprioception. These factors as crucial components of physical fitness play a significant role in injury prevention and overall performance8,9,10. As such, muscle strength is essential to generate physical power during maneuvers such as takedowns, throws, and escapes11. Additionally, balance plays a crucial role in maintaining stability during dynamic movements, which is essential for agility and injury prevention in the fast-paced and unpredictable situation of wrestling matches12. Moreover, proprioception is the body’s innate ability to sense its position in space, enabling wrestlers to coordinate movements effectively, anticipate opponents’ actions, and react swiftly to positional changes on the mat or during a match13.

Despite drawing upon existing literature and pragmatic research in the fields of sports science, various research covered a range of topics related to muscle balance, strength training, agility, plyometric training, resistance training programs, and the effects of training interruptions on athletic performance14,15,16,17,18,19,20. While some studies provided insights into the physiological and psychological implications of training disruptions and strategies, they may not specifically address wrestling. However, they offered evidence-based recommendations for optimizing training protocols and enhancing athlete performance to decrease their negative effects21,22,23. Additionally, some authors have addressed traumatic risk factors in athletes such as reducing isokinetic strength, balance, and proprioception concerning the occurrence of injuries in wrestling24,25,26. However, no research explicitly has focused on wrestling and the negative effects of training disruptions.

For developing targeted training programs and injury prevention strategies, it is required to understand the association between internal risk factors, including strength, balance, and proprioception. By identifying and addressing potential weaknesses in these areas, coaches and athletes can optimize performance while minimize the risk of injuries. As a result, we investigated some internal risk factors for injuries in elite wrestlers due to the functional importance of muscle strength and balance in wrestling. To develop targeted training programs and effective injury prevention strategies, it is essential to understand the impact of reduced training on key internal risk factors such as strength, balance, and proprioception. The physiological adaptations gained through consistent training can gradually diminish or be completely lost when training is discontinued or significantly reduced. Therefore, this decline in neuromuscular function may increase injury risk and affect athletic performance. Given the functional importance of muscle strength and balance in wrestling, our study investigated how wrestling-specific detraining affect these key internal risk factors in elite wrestlers. We hypothesized that wrestling- specific detraining make changes in athletes’ physical conditioning and skill. Thus, the objective of the present study was to determine the isokinetic strength of the flexor and extensor muscles of the knee and shoulder, knee proprioception, and dynamic balance among young male elite wrestlers before and after a 10-week period of wrestling-specific detraining.

Results

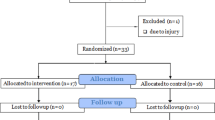

In this study, data from 63 out of 75 wrestlers were analyzed, with 12 declining participation in the follow-up analysis.

Isokinetic strength of knee muscles

The t-test revealed significant differences between concentric and eccentric isokinetic strength of knee extensor and flexor muscles, as well as between mean power during extension and flexion movements at all examined angular velocities, at both baseline and follow-up(P < 0.001 for all comparisons). However, Table 1 demonstrates no significant difference in the ratio of isokinetic strength between knee flexor and extensor muscles at any of the investigated angular velocities (P = 0.85 at 60°/s, P = 0.63 at 180°/s, P = 0.40 at 300°/s).

Isokinetic strength of shoulder muscles

Table 2 displays comparable results regarding the shoulder flexor and extensor muscles. The concentric and eccentric isokinetic strength of shoulder extensor and flexor muscles differed significantly at all angular velocities during extension and flexion movements both at baseline and at follow-up (P < 0.001 for all comparisons). However, no significant difference was noted in the ratio of isokinetic strength between the shoulder flexor and extensor muscles(p = 0.10, p = 0.54, p = 0.99).

Knee joint proprioception

Knee joint proprioception was measured and recorded using two methods. The first test assessed proprioception through active knee movement and angle reproduction at angles of 30, 60, and 90°. The second test measured the detection of passive knee motion during flexion and extension movements at a 90° angle. The results of the t-test indicated significant differences in knee joint proprioception during angle reproduction at 30, 60, and 90° of active movement, as well as in the detection of passive extension and flexion knee movements (Table 3).

Dynamic balance

The t-test revealed significant differences in all balance indexes—including the overall balance, anterior–posterior balance, and medial–lateral balance in the left and right legs—before and after periods of reduced mobility due to wrestling -specific detraining (Table 4).

Discussion

The present study aimed to examine the impact of a 10-week wrestling-specific detraining on key injury risk factors in elite young wrestlers. We assessed changes in concentric and eccentric isokinetic strength of the knee and shoulder flexor and extensor muscles, knee proprioception, and dynamic balance. The findings indicated a significant reduction in isokinetic strength in the respective muscles, measured at angular velocities of 60, 180, and 300° per second.

Additionally, evaluating muscle strength in athletes and isokinetic torque assessment is one of the most commonly used methods. It is considered a valuable diagnostic tool for assessing sports injury risk, understanding injury mechanisms, and guiding rehabilitation. Understanding the impact of detraining, posing by various factors, can provide valuable insights for researchers27.

Discontinuation of specific exercises, influenced by factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic, is predicted to lead to physiological deconditioning, underscoring the potential impact of prolonged detraining on key neuromuscular characteristics28.

Most studies have focused on football and have investigated the effects of sport- specific detraining and its subsequent negative effects. For example, Moreno‐Pérez et al. (2020) reported similar results in a study involving 30 semi-professional football players in Spain. They measured the eccentric strength of hamstring muscles at three stages on days 14, 28, and 49 after the start of detraining, concluding that periodic detraining led to a decrease in eccentric strength23. In addition, they demonstrated a significant reduction in the eccentric strength of knee flexor muscles in football players who did not undergo supervised training over a long period23.

Scoz et al. (2022) investigated changes in the isokinetic strength of professional football players from two different Brazilian football teams (A and B) during the COVID-19 quarantine period. The study compared two home-based training approaches over a 6-week quarantine period. Team A implemented supervised training routines via video calls, while Team B did not utilize the usual exercise monitoring strategy. Results indicated no significant decrease in knee extensor or flexor torque in Team A. However, Team B experienced a significant decrease in isokinetic strength of knee flexors. These findings suggested that exercise supervision may enhance players’ adherence to training routines and diminish the adverse effects of prolonged sport-pecific training periods29. Another study reported a significant increase in body fat percentage among professional football players after a 7-week detraining period, compared to a 5-week transitional period. During the transitional period, the players followed a structured training program that included strength and muscle exercises three times a week, along with cardiovascular and respiratory exercises four times a week30.

On the other hand, Waldén et al. (2022) conducted a prospective study involving 19 teams across 12 countries, collecting data on player injuries and time loss. The results demonstrated that prolonged absence from sport -specific training did not lead to an increased incidence of injuries during matches or an increase in the injury burden31. Keemss et al. (2022) supervised eight professional football players from a Bundesliga team using video tracking programs while they trained five to six days per week. They found that, even without in-person training, the players maintained their body composition and physical performance. Their findings suggested that effective remote supervision during quarantine can help preserve both fitness and body composition32.

Based on the current findings, the accuracy of proprioceptive joint position sense decreased at angles of 30, 60, and 90 degrees, along with a reduction in dynamic balance among the wrestlers. These results suggest that long-term wrestling-specific detraining may contribute to declines in muscle strength, as reported in previous studies33,34. Similarly, Fathi et al. (2018) observed that sport-specific detraining may lead to muscle strength reductions, potentially affecting sensory receptors in muscles and joints35. This has been attributed to decreased stimulation and activity of these receptors36. However, since our study did not directly assess sensory receptor activity, this remains a possible explanation rather than a confirmed finding.

Consequently, this phenomenon can disrupt the function of the sensory-motor system in the long term. Mechanoreceptors, which transmit information and initiate the feedback loop of proprioceptive sensation, play a crucial role in joint proprioception, muscular tone control, and the generation of reactive responses. Long-term detraining and lack of engagement of sensory receptors can lead to muscle inhibition, atrophy, and weakness. Therefore, it can disrupt the transmission of sensory information from existing sensory receptors by exerting inhibitory effects on muscles37.

Furthermore, it is important to note that sport-specific detraining leads to a decrease in type II muscle fiber size, reduced central nervous system sensitivity to exercise, a decline in motor unit recruitment, and limitations in motor unit activation capacity38. Changes in the control programs sent from the central nervous system can also be linked to disruptions in proprioceptive joint position sense accuracy due to reduced physical activity39. Any alteration, disturbance, or improvement in motor control programs relies on the sensory information sent from the proprioceptive joint position sense system40. Inadequate proprioceptive sensation due to detraining results in improper execution of movements, inability to respond effectively to sudden demands, and inhibits the proper adaptation of the neuromuscular system to the athlete’s functional needs41.

Our findings align with this principle suggesting that neuromuscular adaptations gained through consistent training gradually diminish when specific-training is reduced or discontinued42. This decline can be observed in isokinetic strength and proprioceptive accuracy following detraining43. Additionally, our results support sensorimotor control theory, emphasizing the role of proprioceptive feedback in maintaining balance and joint stability. Similar findings have been reported in other combat sports, reinforcing the need for targeted neuromuscular retraining following detraining periods44.

Although 10 weeks may seem relatively short compared to an athlete’s long-term training history, previous studies in high-performance sports have demonstrated that even brief periods of detraining can lead to significant declines in neuromuscular function and physical performance45,46.

Limitations

One of the limitations of the present study is its laboratory-based measurement methods that may not fully reflect how the studied variables translate into real-life wrestling performance and injury risk. Future research should consider incorporating field-based assessments to enhance ecological validity. Further, the researchers were unable to fully control the participants’ daily activities or additional exercises during the 10-week period, that may have influenced the results. The drop-out of 12 individuals who did not participate in the follow-up due to personal reasons reduced the sample size, potentially impacting the statistical power of the study.Future studies should consider strategies to minimize dropout rates.Moreover, the lack of control over the psychological and mental state of the participants during sport-specific detraining can lead to changes in motivation, mental fatigue, and overall psychological well-being, which may have affected the participants’ performance during the assessments.

Given the nature of the study design (prospective comprehensive), the primary aim was to examine the within-subject effects of a wrestling-specific detraining period on strength, proprioception, and balance. Future studies could include a control group to enhance the ability to compare these effects against athletes who do not undergo a detraining, offering more robust conclusions.

Conclusion

The findings of this study revealed that a 10-week period of reduced wrestling-specific training—implemented due to factors such as injury, illness, or external circumstances like the COVID-19 lockdown—resulted in decreased concentric and eccentric strength of the shoulder and knee flexor and extensor muscles, as well as impairments in proprioceptive joint position sense and dynamic balance. These alterations substantially increase the risk of injury among athletes, particularly in wrestling. Therefore, it is essential to assess variables such as muscle strength, proprioceptive accuracy, and dynamic balance in wrestlers following prolonged periods of wrestlers-specific detraining before they return to full competition.

Based on these findings, coaches and sports specialists should prioritize the specific training components (e.g., strength, proprioception, and dynamic balance) after extended sport-specific detraining to minimize the risk of injury. A structured return-to-training protocol, which includes progressive strength training and proprioceptive exercises, may help mitigate the negative effects of reduced training intensity.

Methods

Experimental approach to the problem

A Prospective Comprehensive Study was conducted on young male elite wrestlers actively engaged in the Tehran Wrestling League, Iran. All subjects experienced a 10-week wrestling-specific detraining due to different situations such as injury, illness, or external circumstances like the COVID-19 lockdown. Study outcomes included the assessment of isokinetic strength of the flexor and extensor muscles of the knee and shoulder, as well as knee joint proprioception at baseline and after a 10-week wrestling-specific detraining at the Shahid Beheshti University (SBU) laboratory. These assessments were conducted using Biodex Isokinetic System Pro 4 (CMVAG Con-Trex, Switzerland). The Biodex Balance System was utilized to evaluate stability parameters during a single-leg stance test, as the secondary outcome.

Subjects

A total of 75 volunteers (mean age: 19.33 ± 3 years, mean height: 174.32 ± 6.8 cm, mean weight: 80.21 ± 22.01 kg, mean body mass index: 25.34 ± 5.89, mean fat percentage: 13.25 ± 5.80) were selected through convenience sampling. To be eligible, participants were required to meet the following criteria: a minimum of 5 years of competitive wrestling experience; age under 21 years; no severe injuries in the past six months; normal limb alignment, as assessed by a certified corrective exercise specialist through a standardized clinical evaluation; and participation in at least three regular training sessions per week. Participants were excluded if they engaged in any additional training beyond their regular team sessions during the study period, including any supplementary wrestling training protocols designed to target specific skills or physical capacities that are not part of the standard training regimen provided by their team.

Ethical considerations

All the participants or their legal guardians provided informed consent before the commencement of the study. The Ethics Committee of the SBU granted ethical approval under No. IR.SBU.REC.1401.028/2021-05-08 following the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration.

Procedures

Isokinetic strength of knee flexor and extensor muscles

Following a 10 min standardized warm-up—during which participants cycled on a stationary bike at their preferred intensity and speed—they were comfortably seated on a chair attached to the Biodex isokinetic dynamometer to assess concentric-to-concentric and eccentric-to-eccentric strength of the hamstring and quadriceps muscles.Standardized positioning of the trunk, pelvis, thigh, and knee was ensured according to the isokinetic device guidelines considering the rotations, heights, and angles. Ensuring participant comfort and stability, they were instructed to perform several natural contractions within the range of motion after adjusting the arm height relative to the length of the leg and securing firmly with a specialized strap and softening pad placed over the ankle. To measure the concentric-to-concentric strength, participants exerted maximal effort and speed during knee flexion and extension within the range of motions: 0 to 90° at angular velocities of 60 degrees per second (low intensity), 180 per second (moderate intensity), and 300 per second (high intensity) for five attempts at each angular velocity, with a 30 s rest interval between attempts, and a 1 min rest between different velocities. Similarly, eccentric-to-eccentric strength measurement was followed the same protocol but at angular velocities of 60 and 180° per second using the device controls and test administrator47.

Knee joint proprioception

We utilized two methods to detect passive motion and active joint position sense threshold, consistent with the previous protocol48. Participants actively moved their legs to the angles (30, 60, and 90 of knee flexion), held the knee in the target position for 5 s, and then returned to the initial position (30 and 60, and 90 ). Subsequently, they repeated the target angles with closed eyes to prevent visual and using earplugs to prevent auditory feedback in three trials considering a 30 s rest between each . Mean error was recorded for analysis49,50. To detect passive motion, consistent with the previous positioning , the participant extended the knee passively from the 0° angle at a speed of 25.0 per second while handhelding key. Then pressed the key as soon as the initiation of motion was detected. The average threshold to detect motion was recorded over three repetitions51. The same protocol was repeated for knee flexion, respectively.

Isokinetic strength of shoulder flexor and extensor muscles

The participant moved the arm along the sagittal plane and performed five repetitions with maximal effort within the range of motions 0 to 180° at three different angular velocities: 60, 180, and 300° per second. The rest period between each repetition was 1 min, and there was a 3-min rest period between each exercise52.

Dynamic balance

We used a single-leg standing protocol in a Biodex balance device ,featuring a graded circular platform (balance board) and is mounted on a large base equipped with multiple sensors allowing for adjustment of its position relative to the horizontal plane in various directions. This platform demonstrates high sensitivity to even minor changes in the center of gravity and can promptly adapt its orientation based on the direction and magnitude of the applied force pressure from the feet. Three deviations of the center of gravity from the center of the support surface were recorded: an overall index, the anterior–posterior, and medial–lateral directions were measured moment by moment. The stability of the balance board ranges from level eight (indicating average stability) to level two (indicating low stability), while the participants maintained their balance at the center of the platform for 20 s53.

Statistical analyses

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS software version 25. At first, the normality of data distribution was assessed for all variables using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Subsequently, upon confirming a normal distribution of the data, a t-test was applied to compare all variables between the baseline and follow-up tests. Mean ± standard deviation, along with the t-value, was reported to quantify the difference between the means. A significance level of 0.05 was considered for this study.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chaabene, H. et al. Physical and physiological attributes of wrestlers: an update. J. Strength Cond. Res. 31(5), 1411–1442 (2017).

Sciranka, J., Augustovicova, D. & Stefanovsky, M. Time-motion analysis in freestyle wrestling: Weight category as a factor in different time-motion structures. Ido movement for culture. J. Martial Arts Anthropol. 22(1), 1–8 (2022).

Lukic-Sarkanovic, M. et al. Acute muscle damage as a metabolic response to rapid weight loss in wrestlers. Biomed. Hum. Kinet. 16(1), 99–105 (2024).

Curby, D. G. COVID-19: Considerations regarding the return to wrestling training. Int. J. Wrestl. Sci. 10(1), 1–14 (2020).

Mujika, I., Padilla, S. & Pyne, D. Swimming performance changes during the final 3 weeks of training leading to the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games. Int. J. Sports Med. 23(08), 582–587 (2002).

Halson, S. L. Monitoring training load to understand fatigue in athletes. Sports Med. 44(Suppl 2), 139–147 (2014).

Prieto-González, P. et al. Epidemiology of sports-related injuries and associated risk factors in adolescent athletes: an injury surveillance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(9), 4857 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Effects of high-intensity functional training on physical fitness and sport-specific performance among the athletes: A systematic review with meta-analysis. PLos One 18(12), e0295531 (2023).

Abuwarda, K., Mansy, M. & Megahed, M. High-intensity interval training on unstable vs stable surfaces: effects on explosive strength, balance, agility, and Tsukahara vault performance in gymnastics. Pedag. Phys. Cult. Sports 28(1), 43–52 (2024).

Zemková, E. Physiological mechanisms of exercise and its effects on postural sway: Does sport make a difference?. Front. Physiol. 13, 792875 (2022).

Murphy, D. & Young, B. The Wrestlers’ Wrestlers: The Masters of the Craft of Professional Wrestling (ECW Press, 2021).

Hossain, K. Leadership development and challenges in twenty-first century. J. Lib. Arts Humanit. 4(9), 1–42 (2023).

Cordero Rojas, Y. et al. The development of the balance coordination capacity in Greek wrestling athletes, initial categories. PODIUM-Revista de Ciencia y Tecnologia en la Cultura Física 15(3), 577–594 (2020).

Myer, G.D., Faigenbaum, A.D., Cherny, C.E., Heidt Jr, R.S. & Hewett, T.E. Did the NFL Lockout expose the Achilles heel of competitive sports? J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 41(10), 702–705 (2011).

Fleck.J, W Kraemer,. Designing Resistance Training Programs (Human Kinetics, 2014).

Impellizzeri, F. M., Marcora, S. M. & Coutts, A. J. Internal and external training load: 15 years on. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 14(2), 270–273 (2019).

McGuigan, M. R., Wright, G. A. & Fleck, S. J. Strength training for athletes: does it really help sports performance?. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 7(1), 2–5 (2012).

Bazyler, C. D., Beckham, G. K. & Sato, K. The use of the isometric squat as a measure of strength and explosiveness. J. Strength Cond. Res. 29(5), 1386–1392 (2015).

Miller, M. G. et al. The effects of a 6-week plyometric training program on agility. J. Sports Sci. Med. 5(3), 459 (2006).

Andrade, A. et al. Sleep quality associated with mood in elite athletes. Phys Sportsmed 47(3), 312–317 (2019).

Haff, G. G. & Triplett, N. T. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning 4th edn. (Human Kinetics, 2015).

Kraemer, W. J. & Fleck, S. J. Optimizing Strength Training: Designing Nonlinear Periodization Workouts (Human Kinetics, 2017).

Moreno-Pérez, V. et al. Effects of home confinement due to COVID-19 pandemic on eccentric hamstring muscle strength in football players. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 30(10), 2010–2012 (2020).

Grazioli, R. et al. Coronavirus disease-19 quarantine is more detrimental than traditional off-season on physical conditioning of professional soccer players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 34(12), 3316–3320 (2020).

Dauty, M. et al. Consequences of the SARS-CoV-2 infection on anaerobic performances in young elite soccer players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(11), 6418 (2022).

Hill, T. M. Impact Load Symmetry Following Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction after Return to Sport in Collegiate Athletes (The University of North Carolina, 2021).

Radzimiński, Ł et al. The influence of COVID-19 pandemic lockdown on the physical performance of professional soccer players: an example of German and Polish leagues. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(16), 8796 (2021).

Stokes, K. A. et al. Returning to play after prolonged training restrictions in professional collision sports. Int. J. Sports Med. 41(13), 895–911 (2020).

Scoz, R. D. et al. Strength level of professional elite soccer players after the COVID-19 lockdown period: a retrospective double-arm cohort study. J. Sports Med. 2022, 1–7 (2022).

Parpa, K. & Michaelides, M. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on professional soccer players’ body composition and physical fitness. Biol. Sport 38(4), 733–740 (2021).

Waldén, M. et al. Influence of the COVID-19 lockdown and restart on the injury incidence and injury burden in men’s professional football leagues in 2020: The UEFA Elite Club Injury Study. Sports Med. Open 8(1), 67 (2022).

Keemss, J. et al. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on physical performance, sleep quality, and health-related quality of life in professional youth soccer players. Front. Sports Act. Living 4, 875767 (2022).

Cengiz, A. & Demirhan, B. Physiology of wrestlersdehydration. Turk. J. Sport Exerc. 15(2), 1–10 (2013).

Beydagı, M.G. & Talu, B. The effect of proprioceptive exercises on static and dynamic balance in professional athletes. Ann. Clin. Anal. Med. 12(1), 49–53 (2021).

Fathi, M. The effect of long-term endurance activity on purβ gene expression in rat fast and slow twitch skeletal muscles. Qom Univ. Med. Sci. J. 12(4), 23–30 (2018).

Aslani, M., Minoonejad, H. & Rajabi, R. Comparing the effect of trx exercise and hoping on balance in male university student athletes. Physi Treat.Specif. Phys. Ther. J. 7(4), 241–250 (2018).

Hadzic, V. et al. The isokinetic strength profile of quadriceps and hamstrings in elite volleyball players. Isokinet. Exerc. Sci. 18(1), 31–37 (2010).

Sadeghi Dehcheshmeh, H., Ghasemi, B. & Moradi, M. R. Comparing the effect of closed kinetic chain exercises and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation on ankle joint proprioception in elderly males. J. Res. Sport Rehabil. 4(8), 55–64 (2016).

Lee, S.J., Dallmann, C.J., Cook, A., Tuthill, J.C. & Agrawal, S. Divergent neural circuits for proprioceptive and exteroceptive sensing of the Drosophila leg. bioRxiv [Preprint]. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.23.590808 (2024).

Winter, L. et al. The effectiveness of proprioceptive training for improving motor performance and motor dysfunction: a systematic review. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 3, 830166 (2022).

Smith, J. W., Holmes, M. E. & McAllister, M. J. Nutritional considerations for performance in young athletes. J. Sports Med. 2015(1), 734649 (2015).

Häkkinen, K. et al. Neuromuscular adaptations during short-term “normal” and reduced training periods in strength athletes. Electromyogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 31(1), 35–42 (1991).

Wang, K. et al. Effect of isokinetic muscle strength training on knee muscle strength, proprioception, and balance ability in athletes with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomised control trial. Front. Physiol. 14, 1237497 (2023).

Riemann, B. L. & Lephart, S. M. The sensorimotor system, part II: the role of proprioception in motor control and functional joint stability. J. Athl. Train. 37(1), 80 (2002).

Zujko-Kowalska, K., Kamiński, K. A. & Małek, Ł. Detraining among athletes—Is withdrawal of adaptive cardiovascular changes a hint for the differential diagnosis of physically active people?. J. Clin. Med. 13(8), 2343 (2024).

Zheng, J. et al. Effects of short-and long-term detraining on maximal oxygen uptake in athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BioMed Res. Int. 2022(1), 2130993 (2022).

Daneshjoo, A. et al. The effects of injury prevention warm-up programmes on knee strength in male soccer players. Biol. Sport 30(4), 281–288 (2013).

Ager, A. L. et al. Shoulder proprioception: how is it measured and is it reliable? A systematic review. J. Hand Ther. 30(2), 221–231 (2017).

Chen, C.-Y. et al. Influence of magnetic knee wraps on joint proprioception in individuals with osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Clin. Rehabil. 25(3), 228–237 (2011).

Hertel, J. et al. Neuromuscular performance and knee laxity do not change across the menstrual cycle in female athletes. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 14, 817–822 (2006).

Lephart, S. M. et al. Proprioception of the shoulder joint in healthy, unstable, and surgically repaired shoulders. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 3(6), 371–380 (1994).

Hutchinson, K. & Winnegge, T. Manual therapy applied to the hemiparetic upper extremity of a chronic poststroke indiviual: Case report. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 28, 129–137 (2004).

Bilgiç, A., Özdal, M. & Vural, M. Acute effect of inspiratory muscle warm up protocol on dynamic and static balance performance. Eur. J. Phys. Educ. Sport Sci. https://doi.org/10.46827/ejpe.v8i4.4309 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the individuals who participated in this study. The authors acknowledge the use of an artificial intelligence tool (ChatGPT) to assist in language polishing and drafting portions of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design (MZ, FH, MN, AH), data collection (MN, AH), data analysis and interpretation (MZ, FH, MN, ZY), and manuscript preparation (MZ, FH, MN, AH, ZY). All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Before the commencement of the study, all the participants or their legal guardians provided informed consent. The Ethics Committee of the SBU granted ethical approval under No. IR.SBU.REC.1401.028, Dated 2021-05-08 following the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Noorbakhsh, M., Zarei, M., Hovanloo, F. et al. Exploring the influence of a 10-week specific detraining on injury risk factors among elite young wrestlers: a prospective study. Sci Rep 15, 7348 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91561-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91561-4