Abstract

The Haba Snow Mountain Tunnel experienced severe deformation caused by foliated metamorphic basalt. This rock has high metamorphism, easy weathering, and low strength. This study examines the rock’s microscopic characteristics and mechanical properties to understand its impact on tunnel stability and offer guidance for similar engineering challenges. Through comprehensive analysis of the rock’s composition and structure, combined with mechanical strength testing, the study establishes strong correlations among uniaxial compressive strength, rebound strength, and point load strength. Key findings reveal that the point load index correlates linearly with uniaxial compressive strength (y = 10.97x, R²=0.93). These results not only enhance the understanding of foliated metamorphic basalt’s properties but also offer practical recommendations for optimizing strength testing methods. This study provides crucial technical references for tunnel design under similar geological conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

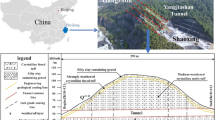

The Haba Snow Mountain Tunnel has experienced severe deformation, as shown in Fig. 1. This event has drawn significant attention and raised concerns about underground construction risks. Located in the northwest of Yunnan Province, China, the Haba Snow Mountain Tunnel is a critical transportation link connecting regional economic zones. Its construction is of significant strategic importance, yet the unexpected deformation observed in foliated metamorphic basalt formations has posed substantial risks to its safety and stability1,2,3,4. Despite the tunnel’s burial depth exceeding 800 m, which may result in significant ground stress, many other deeply buried tunnels have experienced deformation without reaching the severity observed in this project. This unique challenge highlights the need for an in-depth understanding of the geological and mechanical behavior of the surrounding rock. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the causes of severe deformation in the Haba Snow Mountain Tunnel, providing both theoretical insights and practical guidance for similar engineering scenarios in complex geological conditions. The excavation of the Haba Snow Mountain Tunnel has revealed the presence of foliated metamorphic basalt formations. This rock, unlike typical basalt, has altered mechanical properties due to metamorphism. It has reduced strength and increased anisotropy, which complicate tunnel stability. A detailed analysis of its mineral composition, microstructure, and mechanical behavior is necessary5.

Rock strength is one of the most critical parameters in tunnel design. Common methods for evaluating rock strength include uniaxial compression tests (UCT), point load tests (PLT), and Schmidt hammer rebound tests (SHRT)6,7. Each method has its own strengths and limitations. For instance, UCTs provide accurate measurements of compressive strength; however, they can be challenging for highly weathered, severely metamorphosed, or low-strength rocks due to difficulties in extracting intact cores8,9. In contrast, PLTs are more adaptable to irregularly shaped or fragile samples, though they yield an indirect estimation of rock strength10. SHRTs are quick and cost-effective but are less suitable for highly fractured or weak rocks, as they rely on surface hardness11. These methods are all considered indirect testing techniques for rock strength12,13. Notably, the PLT features a straightforward testing process and sample preparation, allowing for the use of various regular cylindrical rock samples or any irregular blocks14,15, applicable to both hard and fragile rocks16,17. To address the limitations of individual testing methods, combining multiple approaches can provide a more comprehensive understanding of rock strength, particularly in complex geological conditions such as foliated metamorphic basalt. This study adopts a combination of UCTs, PLTs, and SHRTs to explore their relationships and validate their applicability for engineering purposes.

Many studies have explored correlations between UCS, PLI, and rebound strength (RS) for different rock types18,19. For instance, Xue et al.19 found a strong linear relationship between UCS and Is(50) in granite. Mohammed et al.20 established empirical formulas to predict UCS using SHRTs on limestone. However, studies on foliated metamorphic basalt are limited, especially regarding the relationships between its strength parameters21,22,23. Therefore, this study first analyzes rocks’ mineral composition and microscopic characteristics through thin section identification, X-ray diffraction (XRD), and scanning electron microscopy testing methods. Then, the rock strength is determined through UCTs, PLTs, and SHRTs. Finally, the mechanical properties of metamorphic basalt and the relationship between different rock strength testing methods are discussed. These findings not only contribute to the understanding of foliated metamorphic basalt but also provide valuable recommendations for strength testing and tunnel design in challenging geological conditions.

The situation of severe deformation in the Haba snow mountain tunnel

In Fig. 2, the foliated metamorphic basalt revealed on the surface and within the excavated section of the Haba Snow Mountain Tunnel exhibits distinct characteristics. The surface-exposed foliated metamorphic basalt displays a relatively fragmented structure, yet the rock blocks demonstrate high strength. However, the foliated metamorphic basalt uncovered during tunnel excavation not only exhibits a fractured structure but also lacks significant strength, with some rock blocks easily crumbling upon manual handling. Unfortunately, the foliated metamorphic basalt revealed within the tunnel undergoes rapid weathering, transitioning into a nearly powdered state within a few hours, resulting in minimal strength. This unique rock formation proves to be a crucial factor contributing to the severe deformation observed in the Haba Snow Mountain Tunnel. Obtaining rock core samples poses considerable challenges due to the fragmented nature of the rock, making it difficult for the drilling core to take shape. Consequently, it becomes imperative to study the lithology and strength determination methods for this type of rock. Understanding these rock characteristics is crucial to promptly identifying the rock’s properties in similar future situations, providing essential technical references for implementing appropriate engineering measures.

Research methods for rock characteristics

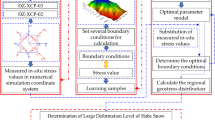

The rock samples are mainly from the Haba Snow Mountain Tunnel, a maximum burial depth of 1155 m, and the primary crossing strata are metamorphic basalt and carbonaceous slate. This article takes metamorphic basalt as the research object. Firstly, the mineral composition and microscopic characteristics of the rock were analyzed through thin section identification, XRD, and scanning electron microscopy testing methods. Given the unique challenges posed by foliated metamorphic basalt, a combination of UCT, PLT, and SHRT was employed to assess rock strength. UCS tests enable precise measurement of compressive strength but require intact cores, which are difficult to obtain for weak or fractured rocks. PLI tests, on the other hand, are advantageous for irregularly shaped or fragmentary samples, making them particularly suitable for the foliated metamorphic basalt found in this study. SHRTs complement these methods by offering a rapid and non-destructive estimation of surface hardness, although their applicability decreases for rocks with compressive strength below 10 MPa. Together, these methods provide a robust framework for analyzing rock strength in challenging conditions. Finally, the mechanical properties of the metamorphic basalt and the relationship between different rock strength testing methods were discussed. The methodology is shown in Fig. 3. We conducted 60 UCTs, 100 PLTs, and 82 SHRTs.

Analysis of the results of rock tests

Mineral composition and microstructure of rocks

The thin section identification method identifies minerals and rocks under a polarizing microscope24,25. It observes and identifies rocks to distinguish their mineral types and studies the main mineral composition, mineral generation sequence, structure, structure, and rock (ore) type of rocks and ores. The thin section identification results are shown in Fig. 4. The mineral composition is shown in Table 1. The rock specimen is green or grayish-green in color, with a porphyritic columnar metamorphic structure and a sheet-like structure. The main minerals are fine granular feldspar and columnar Actinolite, containing a small Chlorite group. The rock contains a minimal amount of carbonate, and a small amount of bubbles slowly form with the addition of dilute hydrochloric acid. The rock has a smaller hardness and can be easily slid with a small knife. The rock was tested by magnetite and found to have weak magnetism. Phenocryst Epidote, columnar Actinolite, and granular Albite can be seen microscopically. In Group A, Albite accounts for a large proportion.

XRD powder crystal diffractometer can be used to study the process and phase transition, surface phases, defects, and crystal structure of mineral crystallization26,27. The XRD results are shown in Fig. 5. The XRD results of the three groups of rocks are similar, and the mineral composition mainly includes amphibole, ferruginous amphibole, plagioclase chlorite group, phlogopite, glauconite, Albite, potassium microcline, magnesium-bearing calcite, rutile, and amorphous materials. The proportion of mineral components varies slightly. The content of epibole and ankerite in Group B is relatively low, but the content of Phlogopite, Glauconite, and amorphous phase materials is slightly higher. Edenite generally occurs in sodium-rich Igneous rock, the contact zone between dolomitic limestone and Igneous rock, and jadeite-bearing albite28. Sodium-rich amphibole mainly occurs in Metamorphic rock formed by sodium rocks29, consistent with Albite in thin section identification. Actinolite is a silicate mineral, which is a mineral formed by replacing more than 2% of magnesium ions in Tremolite with divalent iron ions. It belongs to amphibole30,31. Albite is a sodium mineral of the plagioclase solid solution series32. The Chlorite group is a layered Silicate mineral, commonly called the Chlorite group, mainly composed of magnesium and iron minerals, namely the plagioclase Chlorite group and oolitic Chlorite group33. Therefore, the XRD test results are consistent with the thin section identification.

Electronic images can observe the surface morphology characteristics, morphology, and distribution of micropores of minerals at nano or micrometer scales34,35, providing a basis for rock evaluation (see Fig. 6). The microstructure of the three sets of rock samples is similar. The microstructure of the rock block sample’s front surface shows many bar-like and rod-shaped structures with staggered morphology. The rock minerals exhibit directional and regular arrangements. The side microstructure has some lamellar and layered structures, which are relatively disordered. A large number of rock fragments and fallen Clay minerals can be seen. In addition, there are relatively more pores on the side of the rock. Actinolite is slightly altered into the Chlorite group, and the Chlorite group appears in the form of curved sheets with angular edges. It is randomly distributed along the edge of the Actinolite crystal.

UCT

Drilling rock cores inside and outside the tunnel for UCT, the results of the UCTs are shown in Fig. 7. It can be seen from Fig. 7 that the minimum uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) of rock is 18.26 MPa, and the maximum UCS is 79.59 MPa, which follows the Normal distribution. The average UCS is about 33.33 MPa. Compared with the strength of surrounding rock in deep buried soft rock tunnels in the past, the average UCS is slightly higher, mainly because the more complex rock during the coring process is easier to core successfully. The drilling rig used in this experiment is a water drill, which uses water during the coring process to reduce the friction between the drill bit and the rock, reduce the temperature of the drill bit, and improve the quality of the drill core. However, during the core drilling process, it was found that harder rocks had a slower drilling speed (0.3–0.6 cm/min), while softer rocks had a faster drilling speed (above 1.0 cm/min), making it challenging to core highly fractured rocks, as shown in Fig. 8. When the UCS of the rock is less than 18 MPa, it is effortless to break the rock core during the drilling process, mainly due to the development of internal cracks in the rock. During the drilling process, the friction force of the drill bit, combined with the action of water, ultimately leads to the fragmentation of the rock core. However, through statistical analysis of the UCS of rocks, it was found that the rock in the tunnel area is relatively soft. In addition, the surrounding rock of the tunnel is not all soft rock, but mainly soft rock, with both soft and hard rocks coexisting. Most of the rock cores taken come from harder rocks.

PLT

The point load index (PLI) is an index test36,37 commonly used to estimate the UCS of rocks. The peak load is used to calculate the corrected point load strength of a sample with a diameter of 50 mm (IS(50)), as shown in Eq. (1) to (4).

Through statistical analysis of 100 sets of rock point load data, the relationship between the height, width, and area of the rock failure section and the peak load is shown in Fig. 9, and the PLI after size correction is shown in Fig. 10. From Figs. 9 and 10, it can be seen that the failure height range of the rock sample is 0.9 ~ 6.8 cm, which has a linear correlation with the peak load: y = 1.4x, and the correlation coefficient R2 = 0.74; The failure width range is 2.4 ~ 16.5 cm, which has a linear correlation with the peak load of loading: y = 0.81x, and the correlation coefficient R2 = 0.72; The failure area ranges from 3.77 to 89.10 cm2 and has a linear correlation with the peak load: y = 0.18x, with a correlation coefficient of R2 = 0.71; The equivalent diameter range of failure is 2.19 ~ 10.65 cm, and the failure load range is 0.6-16.9kN; The PLI (Is (50)) ranges from 0.16 to 9.32 MPa, with an average value of 2.16 MPa, which shows a typical Normal distribution. In the PLT, most rock failure occurs from the connected joint surface or crack surface, as shown in Fig. 11.

SHRT

The rebound strength point and bar charts are shown in Fig. 12 by conducting SHRTs inside and outside the tunnel. As shown in Fig. 12, the RS ranges from 12.12 ~ 58.99 MPa, with an average value of 28.42 MPa. Generally speaking, the RS of C30 concrete is above 34.2 MPa, indicating a lower rebound strength of rocks. However, the minimum RS is 12.12 MPa, which may also be determined by the strength testing method. Rocks below this value cannot accurately determine the rock’s RS because the instrument has specific impact energy, which may break the rock. Of course, the above results include the test results inside and outside the tunnel. During the tunnel test, the RS of the unexcavated rock can be directly measured. Due to the strong constraints of the unexcavated rock mass, it is easier to conduct SHRTs, while tests outside the tunnel focus on relatively complete blocks of rock.

Discussion

Through experiments, this study obtained 100 sets of PLTs, 82 sets of SHRTs, and 60 sets of UCTs data for metamorphic basalt. It fitted them, as shown in Fig. 13. The results highlight the complementary nature of these methods: UCS tests provided the most reliable and precise compressive strength measurements but were limited by the difficulty of obtaining intact cores from weak or fractured metamorphic basalt. In contrast, PLI tests demonstrated strong correlations with UCS results (R² = 0.93), confirming their suitability as an indirect method for estimating compressive strength when core extraction is infeasible. SHRTs, while less correlated with UCS (R² = 0.76), were particularly effective for rapid assessments of surface hardness, making them useful in preliminary site investigations. These findings underscore the value of combining these approaches to mitigate the limitations of individual methods and to provide a more comprehensive assessment of rock strength.

The UCS of rocks shows a linear correlation with both RS and PLS. For PLI, the relationship is y = 10.97x, with a high correlation coefficient of 0.93. The measured UCS ranges from 1.76 to 102.24 MPa, with an average of 23.7 MPa. For SHRTs, the relationship is y = 1.26x-7.39, and the correlation coefficient is 0.76, which is lower than for PLI. The blue area represents a 95% confidence zone. As the PLI increases, the confidence zone of the relationship between the PLI and UCS increases; As the RS increases, the confidence region of the relationship between rebound and UCS first decreases and then increases. Therefore, for the determination of the strength of weak surrounding rock, considering the characteristics of rock rebound strength, it is recommended to use a comprehensive method of PLT and UCS to determine.

The relationship between the UCS of rocks and the PLI has been extensively studied in the literature38, including cases with intercepts of 0 and non-0. However, the loading methods of PLT and UCT are similar, with gradually increasing loads at the upper and lower ends, but the loading forms are different. Based on this, using a linear formula with an intercept of 0 is recommended to fit the relationship between the UCS of rocks and the PLI. The rebound instrument loading method differs from the above two methods. It mainly obtains the surface strength of the rock through immediate energy impact. When the rock is relatively soft, this loading method is not applicable. The above research shows that the rebound instrument is only suitable for testing the rebound strength of concrete or rock with pressure not less than 10 MPa.

Conclusion

The Haba Snow Mountain Tunnel has experienced an exceptionally rare and severe deformation, with foliated metamorphic basalt identified as one of the primary causative factors. The foliated metamorphic basalt revealed during the tunnel excavation is particularly distinctive, exhibiting significant metamorphism, susceptibility to weathering, and extremely low strength. Consequently, further exploration is warranted into the microscopic characteristics of the rock and methods for determining its strength.

In-depth analysis of mineral composition and microstructure in the Haba Snow Mountain Tunnel, particularly foliated metamorphic basalt, revealed prevalent minerals like actinolite, albite, chlorite, epidote, hornblende, calcite, and metal minerals. XRD supported these findings, while electronic images illustrated surface features including bar-like structures and layered patterns. The uniformity observed in thin section identification, XRD, and electronic images underscores the trustworthiness of our analytical methods. These insights are pivotal for comprehending rock characteristics and informing future tunnel designs in analogous geological contexts.

This study involved the application of three distinct test methods across multiple test groups, encompassing 60 sets of UCTs, 100 sets of PLTs, and 82 sets of rebound tests. The objective was to establish correlations among the results obtained from these diverse testing methodologies. The findings indicate that, for metamorphic basalt, a linear relationship exists between the UCT of the rock and both rebound strength and point load strength. Specifically, the relationship between the PLI and the UCT of the rock is expressed as y = 10.97x, demonstrating a high correlation coefficient of 0.93. In contrast, the relationship between rebound strength and UCT is described by y = 1.26x-7.39, yielding a correlation coefficient of 0.76, which is slightly lower than that observed for PLT.

To determine the strength of weak surrounding rocks, a combined approach using PLTs and UCTs is recommended. This study demonstrates that combining these methods effectively compensates for the limitations of individual tests. For instance, PLI are invaluable for irregular or fragmented samples, while UCTs provide high accuracy when intact cores are available. Rebound tests complement these methods by enabling rapid, non-destructive evaluations of surface hardness. Together, these methods form a robust framework for assessing the mechanical properties of foliated metamorphic basalt, offering practical insights for tunnel design and stability analysis in complex geological conditions.

Data availability

All data, models, or codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Guo, P. et al. Soil creep effect on Time-Dependent deformation of deep braced excavation. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022(1), 5655592 (2022).

Zhang, B., Tan, Z., Zhao, J., Wang, F. & Lin, K. Research on stress field inversion and large deformation level determination of super deep buried soft rock tunnel. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 12739 (2024).

Zhao, J., Tan, Z., Zhang, B. & Wang, F. Stress-Release Technology and Engineering Application of Advanced Center Drifts in a Super-Deep Soft-Rock Tunnel: A Case Study of the Haba Snow Mountain Tunnel (Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2024).

Zhao, J. et al. Large Deformation Characteristics and Mechanisms of Deep-Buried Foliated Basalt Tunnel: A Case Study of the Haba Snow Mountain Tunnel (Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2024).

Jiang, N., Guo, P., Zhang, H., Lu, F. & Liu, J. Mechanical behavior of a new similar material for weathered limestone in karst area: an experimental investigation. Appl. Rheology. 33 (1), 20220154 (2023).

Gao, H. et al. Relationship between rock uniaxial compressive strength and digital core drilling parameters and its forecast method. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 8, 605–613 (2021).

Wang, R. H., Jiang, Y. Z., Guo, J. L. & Tang, T. C. Study on the relation between uniaxial compressive strength and point load strength. Appl. Mech. Mater. 501, 282–285 (2014).

Broch, E. & Franklin, J. A. The point-load strength test. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 9 (6), 669–697 (1972).

Brook, N. The equivalent core diameter method of size and shape correction in point load testing. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 22 (2), 61–70 (1985).

Basu, A. & Kamran, M. Point load test on schistose rocks and its applicability in predicting uniaxial compressive strength. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 47 (5), 823–828 (2010).

Kahraman, S. & Gunaydin, O. The effect of rock classes on the relation between uniaxial compressive strength and point load index. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 68 (3), 345–353 (2009).

C¸obanog˘lu I˙,C¸elik SB. Estimation of uniaxial compressive strength from point load strength, Schmidt hardness and P-wave velocity. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 67 (4), 491–498 (2008).

Fener, M., Kahraman, S., Bilgil, A. & Gunaydin, O. A comparative evaluation of indirect methods to estimate the compressive strength of rocks. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 38 (4), 329–343 (2005).

American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM). Standard test method for determination of the point load strength index of rock and application to rock strength classifications, D5731-08 (2008).

International Society for Rock Mechanics (ISRM). Suggested method for determining point load strength: ISRM comm on testing methods. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 22 (4), 112 (1985).

Heidari, M., Khanlari, G., Torabi Kaveh, M. & Kargarian, S. Predicting the uniaxial compressive and tensile strengths of gypsum rock by point load testing. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 45 (2), 265–273 (2012).

Tsiambaos, G. & Sabatakakis, N. Considerations on strength of intact sedimentary rocks. Eng. Geol. 72 (3–4), 261–273 (2004).

Hak Joon Kim. Estimation for the uniaxial compressive strength of rocks in Korea using the point load test. Tunnel Underground Space 28(1), 72–96 (2018).

Xue, Y. et al. Using indirect testing methods to quickly acquire the rock strength and rock mass classification in tunnel engineering. Int. J. Geomech. 20 (5), 05020001 (2020).

Mohammed, D. A., Alshkane, Y. M. & Hamaamin, Y. A. Reliability of empirical equations to predict uniaxial compressive strength of rocks using Schmidt hammer. Georisk: Assess. Manage. Risk Eng. Syst. Geohazards. 14 (4), 308–319 (2020).

Çobanoğlu, İ. & Çelik, S. B. Assessments on the usability of wide wheel (Capon) test as reference abrasion test method for Building stones. Constr. Build. Mater. 151, 319–330 (2017).

Daoud, H. S. D., Rashed, K. A. R. & Alshkane, Y. M. A. Correlations of uniaxial compressive strength and modulus of elasticity with point load strength index, pulse velocity and dry density of limestone and sandstone rocks in Sulaimani Governorate, Kurdistan region, Iraq. J. Zankoy Sulaimani Part. (Pure Appl. Sciences) 19, 57–72 (2017).

Sengun, N., Altindag, R., Demirdag, S. & Yavuz, H. P-wave velocity and Schmidt rebound hardness value of rocks under uniaxial compressional loading. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 48 (4), 693–696 (2011).

Liu, H. et al. Rock thin-section analysis and identification based on artificial intelligent technique. Pet. Sci. 19 (4), 1605–1621 (2022).

Wu, S., Yu, Z., Kang, J., Zhang, Y. & Gao, P. Research on the anisotropy of thermal conductivity of rocks in Songliao basin, China. Renew. Energy. 179, 593–603 (2021).

Banko, L., Maffettone, P. M., Naujoks, D., Olds, D. & Ludwig, A. Deep learning for visualization and novelty detection in large X-ray diffraction datasets. Npj Comput. Mater. 7 (1), 104 (2021).

Kochetov, V. et al. Powder diffraction computed tomography: a combined synchrotron and neutron study. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 33 (10), 105901 (2020).

Zhao, F. F. et al. Geochemistry trace of metallization for polymetal field in Yangjiaba, Lueyang, Shanxi Province. Acta Petrol. Sin. 26, 1465–1478 (2010).

Parnell, J., Boyce, A. J. & Næraa, T. Seawater signatures in the supracrustal Lewisian complex. Scotl. Geol. Magazine. 159 (9), 1638–1646 (2022).

Akolkar, G. & Limaye, M. A. Mineral chemistry and reaction textures of Calc-silicate rocks of the Lunavada region, SAMB, NE Gujarat. J. Geol. Soc. India. 97, 151–157 (2021).

Pan, Y. & Fleet, M. E. Calc-silicate alteration in the Hemlo gold deposit, Ontario; mineral assemblages, PTX constraints, and significance. Econ. Geol. 87 (4), 1104–1120 (1992).

Zhou, H. et al. Insights into the floatability between spodumene and albite from crystal chemistry standpoint. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 32 (6), 1329–1339 (2022).

Kurnosov, V. B., Sakharov, B. A., Geptner, A. R., Konovalov, Y. I. & Goncharov, E. O. Clay minerals in sediments from contact zones with basalt sills. Lithol. Min. Resour. 54, 221–235 (2019).

De Castro, B., Benzaazoua, M., Chopard, A. & Plante, B. Automated mineralogical characterization using optical microscopy: review and recommendations. Miner. Eng. 189, 107896 (2022).

Guanira, K. et al. Methodological approach for mineralogical characterization of tailings from a Cu (Au, Ag) Skarn type deposit using QEMSCAN (Quantitative evaluation of minerals by scanning Electron Microscopy). J. Geochem. Explor. 209, 106439 (2020).

Fan, J., Guo, Z., Tao, Z. & Wang, F. Method of equivalent core diameter of actual fracture section for the determination of point load strength index of rocks. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 80, 4575–4585 (2021).

Şahin, M., Ulusay, R. & Karakul, H. Point load strength index of half-cut core specimens and correlation with uniaxial compressive strength. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 53, 3745–3760 (2020).

Tandon, R. S. & Gupta, V. Estimation of strength characteristics of different Himalayan rocks from Schmidt hammer rebound, point load index, and compressional wave velocity. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 74 (2), 521–533 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52408425). Supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under Grant Number GZC20240875.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52408425). Supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under Grant Number GZC20240875.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.S. Tan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Supervision. J.P. Zhao: Investigation, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Z.L. Li: Data curation, Writing - review & editing. B.J. Zhang: Investigation, Writing - review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, Z., Zhao, J., Li, Z. et al. A study on surrounding rock characteristics inducing severe large deformation in tunnels and methods for determining its strength. Sci Rep 15, 7011 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91609-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91609-5