Abstract

When auxiliary tunnels pass through gas-bearing strata, there is a risk of gas explosion, but there is less analysis on the impact of gas explosions on operating railways after the auxiliary tunnels are sealed post-construction. To address the shortcomings of existing research, this paper establishes a numerical model of intersecting tunnels that closely resembles actual conditions. It first studies the law of gas explosion in the closed tunnel, obtaining the overpressure curve of the gas explosion. Based on this, the evolution law of plastic expansion of blocking walls of different thicknesses and at different positions under explosive impact is derived, and the safe thickness of the blocking wall is fitted. The study shows that: in the sealed auxiliary tunnel after construction, the overpressure of the gas explosion initially tends to be stable, then increases rapidly, and finally tends to be stable, with the peak value being up to 0.79 MPa. The duration of the explosion increases with the increase of the tunnel length, and the explosion pressure decreases as the tunnel length increases; under the condition of the highest explosion pressure, the maximum deformation of the blocking wall after the gas explosion is 36.7 mm, the shear strain at the center position of the wall surface is the largest, and the range of tensile shear damage is larger, which is a severely damaged area. The final determination establishes that the minimum safe thickness of the wall is 8.33 m.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Railway transportation plays a pivotal role in alleviating transportation pressures as a vital component of the transportation infrastructure. Over the past two decades, China has witnessed a rapid development in railway tunnel construction, with an increasing number of tunnels being built under complex geological conditions1,2. During the construction process of tunnels, harmful gases such as methane can accumulate within the tunnel, potentially leading to explosions that pose a severe threat to the lives of workers3. Therefore, to prevent gas disasters from occurring after the post-construction blocking of tunnels, it is necessary to conduct research on the patterns of gas explosions within tunnels and the response characteristics of the blocking walls.

In the field of gas explosion patterns and flame propagation, Yan and Du4 conducted an analysis of the explosion effects in subway tunnels and summarized the overpressure from detonations, proposing computational formulas. Within the tunnel, the size of the pressure relief plate, the failure pressure, and the internal congestion significantly affect the explosion pressure5. Fang et al.6 took into account various factors such as changes in the cross-sectional area, wall roughness, and obstacles within the tunnel. Salzano et al.7 investigated the impact of concentration and initial pressure on the peak overpressure increase rate and the combustion rate through hydrogen-methane-air explosion tests in a 5-L vessel. During a gas explosion in a tunnel, the gas concentration results in the maximum overpressure at 9.5%8. Cheng et al.9 and others found that the initial state of gas accumulation primarily influences the initial propagation process of the explosion. By constructing a Bayesian Network (BN) to calculate the probability of gas leakage and utilizing Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) to simulate the diffusion and explosion outcomes of the gas10. Kundu et al.11 and others discovered that the presence of turbulence can enhance the peak overpressure of a gas explosion in an enclosed spherical chamber by 3/54. The gas explosion in a utility tunnel can be divided into three stages based on the development of pressure and flame: the spontaneous rise phase, the oscillating rise phase, and the oscillating decline phase12, In the open literature, there are few researches on the wall under the action of gas explosion. It is worth noting that the blast loads generated by gas explosions have very different characteristics such as lower amplitude, longer rise time, longer duration and possibly multiple peaks13,14, this is different from a high explosive load.

The concrete blocking wall is a powerful means to prevent the further expansion of gas disaster in the tunnel. In order to analyze the response of the closed wall under the action of explosion impact load, Li et al.15 investigated the performance of reinforced clay walls under the action of gas explosions, noting a significant reduction in maximum displacement and damage levels with increased wall thickness and reduced height. Wang et al.16 combined experimental and numerical simulation methods to study the gas explosion process and its destructive effects, discussing the propagation of explosive shockwaves within buildings. In a highly obstructed environment, the explosion of 4.0–4.1 cubic meters of combustible gas is sufficient to destroy a large number of walls, with a maximum indoor overpressure reaching 1.130 bar, and the formation of a 10-m high-pressure damage zone and a 14-m high-temperature damage zone outdoors17. Zhang et al.18 studied the impact of explosion load on the stability of mine seals, considering factors such as seal thickness, depth of cut into the surrounding rock, type of surrounding rock, and roof convergence. Meng et al.19 studied the effect of methane-air explosion in a full-scale concrete tunnel, summarized its pressure characteristics, and used a corrected numerical model to study the structural response of concrete specimens under trapping pressure.

Although there have been many studies on explosion propagation law, structural response and structural reinforcement in confined Spaces, there are few studies on plastic expansion law of gas explosion and safe critical thickness of blocking walls with different thicknesses in the case of auxiliary tunnel closure. Therefore, this paper starts with gas explosion characteristics in closed tunnels after construction. The impact pressure and temperature characteristics of gas explosion in sealed tunnel are simulated. On this basis, the effect of explosion impact on the inner blocking wall of the tunnel is studied. The simulation results can provide reference for the prevention of gas accidents in tunnels containing gas.

Fundamental equation

During a gas explosion in an enclosed tunnel, it is a process of shock wave propagation within a confined space. In the Cartesian coordinate system, the following conservation laws and equations must be satisfied20:

Mass conservation equation:

Momentum conservation equation:

Energy conservation equation:

Equation of State:

where x, y, and z are coordinate parameters; ρ is the fluid density, kg/m3; p is the pressure, Pa; u, v, and w are the velocities in the three coordinate directions, m/s; t is the time coordinate; T is the temperature, K; R is the gas constant; and e is the specific energy, kJ/kg, \(e = \frac{p}{\gamma - 1} + \frac{{\rho \left( {u^{2} + v^{2} + w^{2} } \right)}}{2}\), γ is the gas index, a constant value.

When the detonation wave collides with the closed wall, reflected waves will be generated, resulting in superimposed waveforms. The superimposed pressure can be calculated as follows21:

where \({P}_{\text{E}}\) and \({P}_{1}\) are the pressure after and the initial pressure before the reflected wave, Pa; \(r\) is the ratio of the specific heat capacity of the reactant to the product, that is, \(r\) = \(\frac{{r}_{1}}{{r}_{2}}\). Assuming that the value of r is 1.28, the final acting pressure on the wall can be obtained by bringing in Eq. (5).

Damage evolution equations for blocking walls

In FLAC3D, the Mohr–Coulomb constitutive model incorporates incremental equations from plastic flow theory, allowing the model to update stress and strain in each incremental step, thereby more accurately capturing the material’s response under dynamic loads. Thus, by treating the wall as a rock-like material, we can determine the plastic damage patterns under explosive impact. Gas explosions generate a large amount of high-pressure gas, and the impact of this gas on the blocking wall and surrounding rock can cause damage to the wall and rock.

When the stress and strain of the rock mass reach a predetermined damage threshold, the elastic modulus of the damaged element is22:

where \(E\) is the elastic modulus of the damage element, GPa; \(D\) is the damage variable; \({E}_{0}\) is the elastic modulus of the lossless element, GPa.

The Mohr–Coulomb yield criterion was used in the computation of the model23.

where F is the shear yield function; σ1 and σ3 are the maximum and minimum principal stresses, MPa, respectively; c is cohesion, MPa; and φ is the internal friction angle of the rock, °.

The damage variable D can be expressed in the probability form of crack density as:

where \({p}_{\text{f}}\) is the probability of rock mass damage and failure; \({C}_{d}\) is the crack density, representing the number of cracks contained per unit volume. It can be seen that the damage coefficient \(D\) is between 0 and 1, corresponding to intact, non-destructive materials and materials with fully developed cracks. Crack density is defined as follows:

where \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are material constants; \({\varepsilon }_{c}\) is the critical tensile strain; \(\varepsilon\) is the equivalent cumulative tensile strain, defined as:

where \({\varepsilon }_{i}\)(i = 1, 2, 3) is the main strain; \(<{\varepsilon }_{i}>\) is valid when it is positive and can be expressed as:

At present, it is still very difficult to determine the critical tensile strain of surrounding rock. In the three-dimensional stress state, the ratio of rock uniaxial compressive strength \({R}_{a}\) to the elastic modulus \(E\) of the structure can be substituted, namely:

where \(K\) is the safety factor. The time \(t\) from critical damage state to fracture state of rock mass is:

where \(\dot{\varepsilon }\) is the uniaxial tensile strain rate of rock mass. In the process of dynamic calculation, During the dynamic calculation process, the ratio of the uniaxial tensile strain difference of the rock between the current time step \({t}_{n}\) and the previous time step \({t}_{n-1}\), \(\left( {\frac{{\varepsilon \left( {t_{n} } \right) - \varepsilon \left( {t_{n - 1} } \right)}}{{t_{n} - t_{n - 1} }}} \right)\), is automatically calculated to update the strain rate, thereby estimating the time for the rock mass to transition from critical damage to fracture.) Thus, the crack density expression can be written as:

where \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are material constants; which are determined by test. Substituting Eq. (14) into Eq. (8), can get:

Equation (15) is a dynamic damage model, and it can be seen that rock mass damage under explosion load is a function of equivalent volumetric cumulative tensile strain and load action time.

Fundamental assumption

Gas explosion is an extremely complex and rapid chemical reaction. In this simulation, the intermediate processes of the chemical reaction are not considered. The following assumptions are made during the simulation calculations: (1) The high-pressure impact force generated by the gas explosion is simplified as an impact load applied to the concrete blocking wall; (2) The temperature effect on the damage of the blocking wall is not considered; (3) It is assumed that the initial state of the gas, such as concentration, pressure, and temperature distribution, is uniform; (4) A gas explosion is a chemical reaction that occurs with extreme rapidity, generating a multitude of intermediate and transient products during the process. This paper considers only a single-step reaction for the coal gas explosion, specifically focusing on the reaction CH4 + O2 → CO2 + H2O, without taking into account any intermediate or instantaneous byproducts.

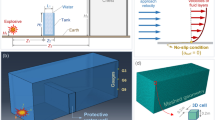

As shown in Fig. 1, this simulation is conducted with the background of a gas tunnel (Transverse tunnel). The transverse tunnel passes through a coal seam in the middle, where gas from the coal seam flows into the tunnel. The left and right end surfaces of the transverse tunnel are sealed, with air outside the end surfaces and rock walls surrounding it.

The numerical simulation in this study is conducted according to the procedure shown in Fig. 2.

Physical model building

To investigate the impact of gas diffusion and aggregation within a gas tunnel (transverse tunnel) on the operation of a main tunnel after an explosion, a three-dimensional numerical simulation was conducted using the FLAC3D finite difference software. This simulation modeled the process of high-pressure gas impacting the sealing explosion-proof wall (hereafter referred to as “the blocking wall”) during a gas explosion and analyzed the damage progression of the blocking wall. Initially, a model of an intersecting tunnel was established with an arch-shaped cross-section, with the model dimensions set to 100.0 m in length, 60.0 m in width, and 100.0 m in height. To simplify the model, the construction of the gas tunnel (transverse tunnel) was horizontally established, and the damage caused by the excavation to the tunnel and the tunnel support were not considered in this simulation. The blocking wall is made of C20 concrete. The failure of the blocking wall and the surrounding rock satisfies the Mohr–Coulomb criterion. The model’s perimeter and bottom are constrained by normal displacement boundary conditions, and the initial velocity and displacement fields of the model are set to zero. The three-dimensional model shown in Fig. 3. Parameter settings are shown in Table 1.

During the numerical simulation calculations, the excavation of the tunnel and the static equilibrium of the model’s self-weight are first completed, followed by dynamic calculations. In the dynamic calculations, based on the previous analysis, a peak pressure is applied as a high-pressure gas stress wave load on the concrete blocking wall. During the dynamic calculations, the static boundary conditions are transformed into free-field dynamic boundary conditions, and the dynamic analysis employs local damping with a damping coefficient of 0.1571. After the simulation is completed, the damage process of the blocking wall is analyzed both qualitatively and quantitatively.

The boundary conditions of the model to simulate the gas explosion are as follows:

-

(1)

In terms of the selection of turbulence models, this study adopted the Large Eddy Simulation (LES) model, which has a good resolution for the changes in vortex structures;

-

(2)

The component model is set as “partial premixed combustion”, the premixing model is C equation (Namely, it is the progress variable equation. Among them, the progress variable C varies between 0 (unburned state) and 1 (fully burned state), reflecting the spatiotemporal advancement of the combustion reaction), the state relationship is “steady state diffusion small flame model”, and GRI mesh 3.0 combustion mechanism is selected;

-

(3)

The wall surface is set to be adiabatic;

-

(4)

For the tunnel models with lengths ranging from 10 to 40 m, both ends are completely sealed. For the 1 km—long tunnel model, the right—hand end is opened and set as a pressure port, and the gauge pressure is 0 Pa;

-

(5)

Create a circular area with a radius of 1 m near the left end face, and ignite the explosion in the area;

-

(6)

The transverse tunnel is set to be filled with 9.5% concentration of gas.

Results and discussion

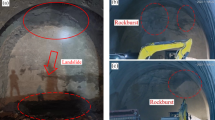

The excavation of tunnels involves various operational conditions, such as inclined shaft conditions, transverse tunnels, and horizontal guidance conditions. During the tunnel construction phase, transverse tunnels facilitate the organization of rapid construction; during the tunnel operation phase, transverse tunnels can be used as entrances and exits or ventilation shafts. This paper takes the transverse tunnel condition as the simulation background. Since there is no outlet for the methane gas that overflows from the coal seam under the condition where both ends of the tunnel are sealed, this situation leads to the highest concentration of methane and the greatest risk of explosion.

It is necessary to know the magnitude of the pressure load acting on the wall by the shock wave of the gas explosion, so the explosion pressure propagation law in the tunnel is first simulated.

Laws of explosive overpressure

In order to investigate the explosion laws of gas tunnels, a small-scale tunnel model with a length of l (ranging from 10 to 40 m) was established, as shown in Fig. 4. Both ends of the model were sealed, and the detonation was initiated on the right side. Pressure monitoring points were set up on the left end face to monitor the pressure changes.

Figure 5 illustrates the overpressure curves of gas explosion in tunnels of different lengths. When the tunnel length is 10 m, within the first second, the explosion pressure has not yet propagated to the measurement point, resulting in minimal pressure change. From 1 to 6 s, the pressure change at the measurement point exhibits a slow-fast-slow variation. Around 6 s, the maximum pressure of 785,000 Pa is reached, indicating the completion of the entire explosion reaction.

The pressure change graph at the monitoring point 20 m away shows that the explosion process reaches 775,000 Pa at 6.3 s, which is slightly later than the 10 m tunnel explosion model, with the overpressure at the completion of the explosion being essentially the same. For a tunnel length of 30 m, the explosion process reaches 774,000 Pa at 6.8 s; with the increase in tunnel length, the time to complete the explosion continues to increase, and the overpressure at the completion of the explosion remains essentially the same. The overpressure curve of the 40 m explosion indicates that as the reaction space increases, the gas explosion in the tunnel exhibits a “formation-development-accelerated propagation” pattern. During the 2–5 s development phase of the explosion reaction, the flame front changes from “convex” to “concave,” and the monitoring point’s pressure shows a fast-then-slow change; from 5 to 11.5 s, the pressure rises rapidly; from 11.5 to 12.5 s, the pressure gradually levels off, reaching 770,200 Pa. The longer tunnel length provides a more expansive reaction space. The increased space allows the gas mixture to spread over a larger area, which in turn slows down the overall reaction rate and the heat transfer and pressure attenuation paths during an explosion in a longer tunnel are also extended. The transfer of heat and the attenuation of pressure affect the combustion rate of the gas and the explosion intensity. Therefore, the explosion reaction time of the 40 m tunnel is significantly extended compared to the 30 m tunnel model, and the gas mass experiences more complex changes during propagation.

Due to the 40 m tunnel length is still small, the establishment of 1 km long tunnel model, as shown in Fig. 6, the model detonation point is set in the left end point, the left end face blocking, the right end face open.

The tunnel is filled with premixed gas, L = Lg, and in the tunnel from right to left to set up seven monitoring points, monitoring the change rule of its pressure over time, to more comprehensive characterization of the impact strength of the tunnel gas explosion.

As shown in Fig. 7, it can be observed that the pressure variations at all monitoring points are relatively consistent. During the initial phase of the explosion, the pressure change is minimal. After 10 s, the pressure rapidly increases, reaching its peak at 14.45 s, with the pressure at point 1 recorded at 53.75 kPa. Following the peak, the pressure drops sharply. In confined spaces, explosive shock waves do not propagate stably; rather, they undergo continuous changes during propagation, resulting in the phenomenon of pressure fluctuations.

Meanwhile, the differences in the pressure peaks at different monitoring points are small, which indicates that the structure of the tunnel responds relatively uniformly at different locations when subjected to dynamic loading. In addition, since the right end of the tunnel was not closed, which acted as a pressure relief hole, there was a difference in the pressure curves from the 10–40 m tunnel section which was closed at both ends. After setting up the pressure relief holes, the pressure decreased to zero after reaching the peak value. Therefore, the next study will focus on analyzing the damage of the blocking wall in the most dangerous case of explosion pressure in order to determine the safe thickness of the blocking wall and provide a scientific basis for accident prevention.

Characterization of the dynamic response of the wall

In order to determine the safe thickness of the wall, the simulated case with the highest impact pressure was chosen as the loading background. From Eq. (5) and the simulated explosion overpressure above, the pressure finally acting on the blocking wall reaches 1.76 MPa, as show in Fig. 8, the dynamic load is loaded onto the blocking wall, which may not necessarily lose its bearing capacity immediately after the wall is impacted in the actual structure, but may last for a certain period of time under the impact and eventually be damaged. Therefore, in the numerical simulation, combining the real situation and the performance of the computer, the calculation time is determined as 1 s to observe the dynamic response characteristics of the blocking wall. Under the impact of explosive loading, shear failure occurs in the wall structure, which leads to the displacement and deformation of the wall24. Therefore, the simulation focuses on analyzing the displacement and plastic zone of the blocking wall, recording the change law of wall displacement and plastic zone with wall thickness.

Law of change of horizontal displacement

A wall with a thickness of 8 m was selected as the monitoring object. Starting from the center of the blast-facing surface (impact surface of the explosion wave) of the wall and extending towards the center of the blast-back surface, measurement points were set up at intervals of 2 m to monitor its displacement changes, as shown in Fig. 9. It can be seen that there was almost no difference in the displacement laws of the wall at different positions. After the explosion occurred, the displacement of the measurement points increased instantaneously and rapidly, reaching the peak when the number of calculation steps was approximately 85,000. Subsequently, it began to decline and stabilize at a certain value. Notably, the peak value of measurement point 1 was significantly higher than those of the other measurement points, while the difference in the peak values of the displacement of the other measurement points was not obvious. This phenomenon also indicates that the explosion shock wave attenuated as it propagated into the interior of the wall.

The position of the blocking wall has almost no effect on the dynamic response of the wall, and the variation rule of thickness-displacement of the wall when the blocking wall is far away from the main hole is the same as that when the blocking wall is close to the main hole.

Figure 10 shows the variation of horizontal displacements of different blocking walls for both cases, It can be seen from the figure that with the increase of the thickness of the wall, the displacement generated by the wall gradually decreases. When the wall thickness is 2 m, the maximum displacement occurs in the center of the wall and a large range of displacement concentration occurs, indicating that the stability of the entire wall is poor. The ability to resist deformation is weakest. After the gas explosion, the high-pressure shock wave load is loaded on the outer wall of the blocking wall in a very short time, so the stress generated in the center of the wall is the largest, and the displacement and deformation generated in the center of the wall are also larger, and the damage occurs in this area first. After the shock wave impacts the wall, it is transformed into stress wave, which continues to propagate in the wall and decreases in the wall. With the increase of the wall thickness, the displacement is still maximum on the outer surface of the wall, and then diffused to the inside of the wall in a decreasing sequence.

The increase in the thickness of the blocking wall enhances its ability to resist explosive shock, resulting in a gradual decrease in the maximum displacement deformation. By fitting the relationship between the maximum deformation displacement and the wall thickness, the variation law of the maximum displacement deformation is obtained, as shown in the Fig. 11.

It can be observed from Fig. 11a that: the maximum displacement of the wall gradually decreases from 34.5 to 23.2 mm. When the thickness of the wall ranges from 2 to 4 m, the maximum displacement decreases greatly, while the decline of 4–8 m is relatively gentle. From Fig. 11b, it can be observed that: the trend of the curve is basically consistent with that of Fig. 11a, the difference is that when the blocking wall is in the center of the tunnel, the maximum displacement for a 2 m wall thickness is 36.7 mm, and for an 8 m wall thickness, the maximum displacement is 21.9 mm. The results indicate that the maximum displacement variation patterns of the blocking wall at different positions within the tunnel are the same, with the maximum displacement deformation decreasing exponentially as the wall thickness increases.

Law of change in the plastic zone

During the force-induced failure process, the plastic zone of the blocking wall also undergoes changes. As shown in Figs. 12 and 13, these figures illustrate the plastic damage and shear strain distribution of the wall when positioned at the left end and center of the tunnel, respectively.

From Fig. 12, it can be observed that as the thickness of the blocking wall increases, the volume of the plastic zone caused by the gas explosion shock on the wall gradually decreases. When the thickness is 2 m, the wall suffers severe overall damage; at 4 m thick, the external surface remains more damaged than the interior, with only a few small areas undamaged. The explosion shock first impacts the blast-facing side, where excessive local stress generates large-scale shear strain. The uneven distribution of stress leads to an uneven distribution of shear strain. Increasing the wall thickness enhances the wall’s shear resistance, and the maximum shear strain decreases as the wall thickness increases. As the wall thickness increases to 8 m, the stress wave has to travel a longer distance within the wall, leading to greater dissipation of energy, significantly reducing the volume of the plastic zone.

From Fig. 13, it can be seen that when the blocking wall is located at the center of the tunnel, away from the primary tunnel, the damage to the wall and the maximum principal strain decrease as the wall thickness increases. With a 2 m thick wall, shear and tensile failure runs through the entire wall. At 4 m thick, there is still a large plastic zone, and the wall is almost completely damaged. With an 8 m thick wall, the internal disturbance is minimal, and only slight shear and tensile failure occurs. The overall plastic zone volume of the wall is smaller than that shown in Fig. 12. This is because when the blocking wall is at the tunnel’s end, the pressure wave generated by the explosion reflects at various points such as the wall and the main tunnel, leading to pressure accumulation and intensifying the wall’s damage. Additionally, as the distance between the blocking wall and the main tunnel increases, the space for absorbing and dissipating energy after the explosion wave penetrates the blocking wall increases, thereby reducing the damage caused by the explosion.

Determination of safe thickness of blocking wall

In order to quantitatively analyze the damage caused by blasting impact on walls of different thickness, the volumes of the global and end-face plastic zones within the model are determined separately using intrinsic FISH functions, and the curve of the plastic volume proportion with the thickness of the wall was fitted, as shown in Figs. 14 and 15.

It can be seen from the Fig. 14 that when the wall thickness is 2 m, 4 m, and 6 m, the volume proportion of the overall plastic zone of the model drops gently, the values are 1, 0.93, and 0.68, respectively. When the wall thickness is 8 m, the volume ratio of plastic zone drops significantly, to 0.46, As the wall thickness increases, the wall absorbs more explosion energy, and the damage of gas explosion to the main tunnel also will weaken. When the wall thickness is 8 m, the proportion of the plastic failure zone at the end surface of the wall is only 0.25, by fitting the formula that when the wall thickness is 8.83 m, the volume ratio of the plastic zone at the blast-back surface of the wall is 0. When the wall thickness is greater than 8.83 m, the gas cannot spread into the positive tunnel through the wall blocking.

As depicted in Fig. 15, wherein (a) illustrates the curve of the overall plastic zone volume ratio of the blocking wall, while (b) presents the proportion of the plastic zone at the blast-back surface of the wall. Observing part (a) of the figure, it becomes evident that as the wall thickness augments, the volume of the plastic zone diminishes progressively. Specifically, the overall plastic volume ratio of the wall declines from 1 to 0.35. Notably, the overall plastic zone volume ratio of the model exhibits a comparable trend to that observed when the blocking wall is positioned at the tunnel’s end. Nevertheless, distinct scenarios emerge in the distribution of the plastic zone at the wall blast-back surface. In part (b) of the figure, the volume ratios of the plastic zone at the blast-back surface of the blocking wall for walls with varying thicknesses are 1, 0.94, 0.71, and 0.11 in sequence. When the wall thickness reaches 8 m, the plastic damage at the wall end surface is conspicuously mitigated. Moreover, when the blocking wall is situated at the center of the tunnel, the plastic volume of the blast-back face of the 8 m thick wall is substantially smaller than that of the 8 m thick wall shown in Fig. 14b.

By fitting the curve formula, it can be determined that when the wall thickness is 8.33 m, the plastic damage of the blast-back surface of the blocking wall is zero. Therefore, to ensure the safety of railway tunnel operations, when setting a blocking wall in the middle of the tunnel, the thickness of the blocking wall should be more than 8.33 m. In order to mitigate the destructive effects of explosions on tunnel walls and ensure the operational safety of the tunnel, enhancing the structural strength is a viable solution. Polyurea coating has been demonstrated through testing to be an effective option for the retrofitting of non-bearing concrete masonry walls25. Recent studies have highlighted the application of reinforcing structures based on elastic polymer materials with potential, such as polyurea26,27.

As the above calculation of the volume of plastic zone based on the maximum overpressure value monitored in the 10 m tunnel, with the same loading method, respectively, 20–40 m long tunnel peak overpressure as the peak pressure loaded onto the blocking wall, resulting in different thickness of the blocking wall with different detonation distances from the impact of the plastic volume of the regional law of change, as show in Fig. 16, the destruction of the plastic zone is still in line with the negative correlation between the wall thickness and the plastic destruction volume of the law, although with the increase in the detonation distance, the role of the pressure on the blocking wall is also reduced, but the peak pressure difference is not large, so the proportion of plastic damage area slightly decreased.

Input energy analysis for complete failure of the blocking wall

To determine the failure of the concrete wall under the action of explosive impact loads, the following three aspects can be considered:

-

(1)

Determine whether the wall will fail by the deformation of the concrete wall after 1 s. Within 1 s after the concrete wall is subjected to impact, it may still be in the development stage of damage and has not completely lost its load-bearing capacity. Damage may only occur after a longer period, so this method of determination is not adopted.

-

(2)

Determine whether the wall will fail by the central horizontal displacement curve of the reinforced concrete wall. This can be considered from two aspects: first, set a value for the horizontal displacement, and when it is reached, judge that the wall is damaged and failed; second, judge whether the wall will be damaged and fail by the final development trend of the horizontal displacement. After the horizontal displacement reaches a certain value, the wall may still be in a balanced state; if the horizontal displacement continues to increase after the impact, it indicates that the wall is still being damaged and may eventually fail. By comparison, using the development trend of horizontal displacement for judgment is more feasible.

-

(3)

Analyze through the destruction of the plastic zone. In the above two simulation cases, the plastic area of the 2 m thick blocking wall reached 100%. With the increase of wall thickness, the plastic destruction area significantly decreases. When the input energy is certain, and when the wall reaches a certain thickness, the explosion cannot completely destroy the wall. Therefore, in order to analyze quantitatively, the proportion of the plastic zone destruction volume reaching 100% is adopted as the criterion for the complete failure of the wall.

From the point of view of energy, the damage failure of the blocking wall subjected to blast load is essentially the energy in the mechanical load, the total input energy generated by the work of the external force (without taking into account the heat exchange between the physical process and the outside world) will be converted into the elastic deformation of the material inside the energy and dissipation of the energy, in which the dissipation of the energy is generated by the material internal structural damage and plastic deformation of the energy is irrecoverable, by the first law of thermodynamics28:

where \(W\) is the work done by the external force, \({U}^{e}\) is the releasable elastic deformation energy, and \({U}^{d}\) is the dissipated energy.

The higher the thickness of the blocking wall, the greater its deformation capacity to resist impact, and the proportion of damage in the plastic zone is also reduced, This is because the gas explosion propagation process is essentially a process of explosion energy propagation and dissipation. The initial energy of the gas explosion is fixed, and the total energy gradually decreases as time goes by. Because the external work is consistent, the thicker the wall, the more dissipated energy required for its deformation, and the overall accumulated elastic strain energy is increased, so the damage range caused by gas explosion is limited.

To obtain the energy input at failure for blocking walls of different thicknesses and positions, which is the work done by external forces, the maximum displacement under various conditions is taken. Based on the dynamic load’s pressure–time curve, the explosive impact on the blocking walls is calculated, assuming that the energy input is the same over an equal period of time. The impact energy for walls that are 4, 6, and 8 m thick is calculated using the proportion of the plastic zone volume, the wall failure energy curve is obtained, as shown in Fig. 17.

Conclusion

This study simulated the overpressure pattern of a gas explosion in a tunnel and the damage caused to the blocking wall by the maximum explosion pressure. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

The overpressure pattern of a gas explosion in a sealed short tunnel shows an initial leveling off, followed by a rapid increase, and finally stabilizes, with the highest overpressure reaching 0.79 MPa. In the 1 km tunnel model with pressure relief vents, the gas explosion pressure exhibits a gradual increase followed by a rapid decay. The hazard of gas explosions in sealed short-length tunnels is more severe.

-

(2)

After the explosion, the central region of the blast-facing side of the blocking wall suffered the most significant damage, with the maximum horizontal displacement of the wall reaching 36.7 mm. As the shockwave attenuates, the horizontal displacement of the wall gradually decreases.

-

(3)

The thickness and position of the blocking wall are critical for safety. Increasing the wall thickness significantly enhances its blast resistance. Placing the wall further from the tunnel’s end also effectively improves its stability. When the blocking wall is positioned at the left end and the center of the tunnel, with thicknesses of 8.83 m and 8.33 m, respectively, no plastic deformation occurs on the back-blast side of the wall.

-

(4)

The dynamic response of the blocking wall to the explosion impact is consistent across different positions within the tunnel. The peak explosion load and the standoff distance are key factors determining the extent of wall damage. When the blocking wall is positioned at the center of the tunnel, the energy required for wall failure is greater than when the wall is located at the tunnel’s end.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, [Bailin Zhang], upon reasonable request.

References

Yan, Q. X. et al. Back analysis of water and earth loads on shield tunnel and structure ultimate limit state assessment: A case study. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 44(5), 4839–4853. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-018-3569-4 (2019).

Yu, H. T., Cai, C., Bobet, A., Zhao, X. & Yuan, Y. Analytical solution for longitudinal bending stiffness of shield tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 83, 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2018.09.011 (2019).

Wang, K. & Du, F. Coal-gas compound dynamic disasters in China: A review. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 133, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2019.10.006 (2020).

Yan, Q. S. & Du, X. L. Forecasting research of overpressure of explosive blast in subway tunnels. J. Vibroeng. 17(6), 3380–3391 (2015).

Tomlin, G., Johnson, D. M., Cronin, P., Phylaktou, H. N. & Andrews, G. E. The effect of vent size and congestion in large-scale vented natural gas/air explosions. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 35, 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlp.2015.04.014 (2015).

Fang, Y. et al. Field tests on the attenuation characteristics of the blast air waves in a long road tunnel: A case study. Shock. Vib. 2019, 11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/9693524 (2019).

Salzano, E., Cammarota, F., Di Benedetto, A. & Di Sarli, V. Explosion behavior of hydrogen-methane/air mixtures. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 25(3), 443–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlp.2011.11.010 (2012).

Yan, Q. S., Zhang, Y. N. & Sun, Q. W. Characteristic study on gas blast loadings in an urban utility tunnel. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 34(4), 14. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)cf.1943-5509.0001477 (2020).

Cheng, C. L., Si, R. J., Wang, L., Jia, Q. S. & Xin, C. P. Explosion and explosion suppression of gas/deposited coal dust in a realistic environment. Fuel 357, 12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2023.129710 (2024).

Bai, Y. P. et al. BN & CFD-based quantitative risk assessment of the natural gas explosion in utility tunnels. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 80, 15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlp.2022.104883 (2022).

Kundu, S. K., Zanganeh, J., Eschebach, D., Badat, Y. & Moghtaderi, B. Confined explosion of methane-air mixtures under turbulence. Fuel 220, 471–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2018.02.043 (2018).

Wang, S. P., Li, Z., Fang, Q., Yan, H. C. & Liu, Y. Numerical simulation of overpressure loads generated by gas explosions in utility tunnels. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 161, 100–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2022.03.014 (2022).

Bao, Q. et al. Experimental investigation on the deflagration load under unconfined methane-air explosions. Fuel 185, 565–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2016.07.126 (2016).

Bao, Q. et al. Effects of gas concentration and venting pressure on overpressure transients during vented explosion of methane-air mixtures. Fuel 175, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2016.01.084 (2016).

Li, Z. et al. Experimental and numerical study on CFRP strip strengthened clay brick masonry walls subjected to vented gas explosions. Int. J. Impact Eng. 129, 66–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2019.02.013 (2019).

Wang, D. et al. Numerical simulation analysis of explosion process and destructive effect by gas explosion accident in buildings. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 49, 215–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlp.2017.07.002 (2017).

Yuan, M. Q. et al. Gas explosion impact behavior and disaster analysis based on structural failure: Numerical modeling. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 87, 14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlp.2023.105234 (2024).

Zhang, X. X. et al. Numerical simulation studies on effects of explosion impact load on underground mine seal. Min. Metall. Explor. 37(2), 665–680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42461-019-00143-2 (2020).

Meng, Q. F. et al. A study of pressure characteristics of methane explosion in a 20 m buried tunnel and influence on structural behaviour of concrete elements. Eng. Fail. Anal. 122, 16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2021.105273 (2021).

Ye, Q., Wang, G. G. X., Jia, Z. Z. & Zheng, C. S. Experimental study on the influence of wall heat effect on gas explosion and its propagation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 118, 392–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.02.084 (2017).

Sun, X. L. et al. Interior Explosion Impact Dynamics 27–38 (Northwestern Polytechnical University Press, 2011).

Xu, J. C., Wang, Z. L. & Rui, G. R. Tunnel slotting-blasting numerical modeling using rock tension-compression coupling damage algorithm. Appl. Sci.-Basel 12(13), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12136714 (2022).

Zhao, H. B. Numerical simulation on pressure behavior of mining field under the conditions of hard roof. Disaster Adv. 4, 15–20 (2011).

Guo, X. et al. A reinforced concrete shear wall building structure subjected to internal TNT explosions: Test results and numerical validation. Int. J. Impact Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2024.104950 (2024).

Santos, A. P. et al. Experimental and numerical study of polyurea coating systems for blast mitigation of concrete masonry walls. Eng. Struct. 284, 14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2023.116006 (2023).

Greene, C. E. & Myers, J. J. Flexural and shear behavior of reinforced concrete members strengthened with a discrete fiber-reinforced polyurea system. J. Compos. Constr. 17(1), 108–116. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)cc.1943-5614.0000308 (2013).

Wu, G. et al. Blast response of clay brick masonry unit walls unreinforced and reinforced with polyurea elastomer. Defence Technol. 18(4), 643–662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dt.2021.03.004 (2022).

Zhang, P. H. et al. A model for rock dissipated energy estimation based on acoustic emission measurements. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2022.1033012 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to give their sincere gratitude for the financial support from Science and Technology Development Plan Project of China Railway Eryuan Engineering Group Co., Ltd. (KSNQ241001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Haoran Hu: writing-original draft; visualization. Bailin Zhang: Supervision; methodology. Xinghua Zhang: Resources. Yong Zhu: Investigation. Lusen Luo: Investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, H., Zhang, B., Zhang, X. et al. Numerical simulation of gas explosion law and determination of safe thickness of blocking wall after auxiliary tunnel blocking. Sci Rep 15, 8593 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91620-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91620-w