Abstract

Armored unmanned vehicles are common targets on battlefields and face many complex threats, such as explosions, gunfire, and drones. Additionally, the threat of explosions that originate underneath the vehicles is a major factor in armored vehicle incapacitation. The underbody explosion protection of lightweight, high-mobility armored vehicles has become a key issue in the design of armored vehicles around the world. To solve this problem, a protective-components-to-chassis (PCTC) protection module was developed during this study. In this design scheme, the protective components were integrated with the chassis to reduce the total number of components. In addition, the total component weight was 37.9% less than that in a traditional protection assembly design. Numerical calculations performed during this study indicated that the proposed protection module is more effective than conventional protective components in armored vehicles. Additionally, the protection effects of the proposed module and a conventional module were compared for equivalent TNT blast impacts. It was shown that the proposed protection module weighed less and exhibited a better protection performance than the conventional protection module. Multi-objective optimization design was also conducted when the protection performance and weight were the optimization objectives. Through the design of experiment (DOE) technique, the effects of the protection module faceplate thickness, beam thickness, tube thickness, and tube diameter on the blast resistance performance of the protection module were analyzed, then the optimal design solution was selected. Finally, the explosion protection properties of the optimal solution were further demonstrated experimentally. The results of this study provide guidance for the design of underbody protective components for armored vehicles, which are especially useful in the design of lightweight and high-mobility unmanned armored vehicles with high protection performance and total weight requirements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Armored vehicles, which are indispensable parts of ground combat assault forces in modern urban warfare, provide force transportation, support, and cover, attract fire, perform fire strikes, and maneuver over obstacles, among other tasks. The widespread use of landmines and improvised explosive devices (IEDs) has caused great risk to the safety of armored vehicles, materials, and crews. Finding ways to improve the anti-explosion protection capabilities of armored vehicles, thereby ensuring the safety of the occupants, has become an important interdisciplinary research topic1. In recent years, to improve the explosion resistance of lightweight and high-mobility armored vehicles, researchers have conducted many studies regarding technologies used to protect the bottoms of armored vehicles. Inclined structures have been widely used for vehicle underbody protection, and the most typical of these are V-shaped structures. Johnson et al.2 used an adaptive domain to obtain a highly accurate optimization solution and proposed a unique V-shaped bottom structure. Rigby et al.3 conducted a systematic experimental study regarding the effectiveness of using V-shaped structures for protection against soil-buried blast impacts. Langdon et al.4 compared the damage and impulse transfer characteristics of single-angle V-plates and composite-angle V-plates. It was demonstrated that composite V-plates offer potential deflection and rupture resistance improvements, but that 120° V-plates provide better impulse transfer characteristics. The optimal angles of single-camber structures cannot be effectively achieved because of vehicle ground clearance amounts, manufacturing processes, and structural attachment methods; therefore, the overall protective capabilities of these structures are less effective than they could be. This is an important issue for the design of underbody protective structures.

Sandwich structures are innovative, lightweight, load-bearing structures with high specific strength and stiffness values, as well as good energy absorption potential, thereby attracting extensive scholarly attention. Nayak et al.5,6 optimized the shape of a honeycomb sandwich structure, thereby effectively reducing the backplate deformation and the impulse transmission acceleration. By studying the impact responses of core-layer materials with functional gradients, Recep et al.7 found that reasonable core-layer design significantly affects the reduction of structural deformation. Jianxun et al.8 predicted the dynamic response of a metal foam core under blast loading conditions throughout experimental and simulation analyses, with good results. Shen et al.9 and Jing et al.10 studied the deformation and collapse modes of curved sandwich panels with different curvatures under blast impact conditions. Hassan et al.11 studied the effects of core density on the explosion resistance of foam sandwich structures. Hause et al.12 investigated the responses of flat anisotropic sandwich panels to explosive pressure pulses. In addition, the weight and protection performance characteristics of protective components are often mutually constrained. Thus, identifying methods of improving the explosion resistance capabilities of protective components while achieving lightweight structures is the key to designing effective protection modules.

Notably, traditional protective component designs cannot meet the increasing armored vehicle protection requirements. Li et al.1 optimized the designs of protective components by applying the six-sigma method, thus improving the robustness of the components. Lan et al.13 numerically analyzed and optimized the dynamic responses of honeycomb sandwich panels by designing a novel curved auxetic honeycomb core, along with a corresponding finite element model. However, few multi-objective studies have been performed to produce designs with better protection characteristics and smaller weights, which are important for the protection needs of lightweight, high-mobility armored vehicles. In addition, little research has been conducted regarding new blast-resistant protective component designs, especially protective-components-to-chassis (PCTC) designs.

During this study, a PCTC module was developed and applied to lightweight and high-mobility armored vehicle protection modules to achieve both excellent protection and low weight characteristics. In addition, the proposed PCTC structure was optimized using multi-objective optimization, for which the objectives were the maximum elastic deformation of the components and the component weight. The rest of this article is organised as follows. Section “Protection module design” describes the anti-explosion component model, and the appropriate simulation analysis method is selected, which obtained the deformations of different protection schemes. Section “Multi-objective optimization and experimental verification” describes the multi-objective optimization method in the optimisation design of vehicle anti-explosion protection components, simulation and experimental results of the optimization scheme are also described. Section “Conclusions” summarises the main conclusions of this paper.

Protection module design

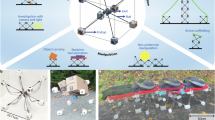

Armored vehicle development is trending toward unmanned vehicles for use in future urban combat. Anti-explosion protection technology for unmanned vehicles has recently become a popular topic of discussion among scholars. In this study, a certain lightweight and high-mobility unmanned armored vehicle was taken as the research object, and a traditional protective component scheme was compared with the proposed PCTC scheme. As shown in Fig. 1, the bottom structure of the lightweight, high-mobility unmanned armored vehicle primarily consisted of four parts: a longitudinal beam, a crossbeam, a connecting seat, and a protected plate that formed the frame. The length of the longitudinal beam was 4000 mm and the bottom of the crossbeam had an angle of 164°. The width of the frame was 915 mm and the dimensions of the protected plate were 1800 × 630 mm. After attaching the anti-explosion protective components, the minimum ground clearance was 400 mm. Since there was a power battery pack on top of the protected plate, there was a requirement that the protective components must not collide with the protected plate during the explosion impact.

Protection schemes

As shown in Fig. 2, two protective component design schemes were investigated. Scheme 1 represents a traditional protective component scheme, in which the traditional protective components and the frame of the unmanned armored vehicle are independent of each other and are connected by a connector. This scheme consists of five parts: a faceplate, a beam structure, aluminum foam, a backplate, and a connector. The total mass of the conventional protective components is 322 kg. The beam structure is welded to the faceplate and aluminum foam is embedded in the beam structure. The connector is welded to the frame of the unmanned armored vehicle, and the faceplate, backplate, and connector are bolted together.

Scheme 2 is the PCTC design. The PCTC module consists of three parts: a faceplate, a beam structure, and a tube. In this scheme, a tube connects the three crossbeams of the unmanned armored vehicle chassis, while the faceplate and the crossbeams are connected by bolts. The beam structure is connected to the body by bolts. The faceplate and the tube predominantly produce the PCTC functionality. The function of the tube is to connect the three crossbeams to form an integral skeleton, which allows the TNT explosion impact energy from any location under the protective assembly to be dispersed through the tube to the three crossbeams after the impact energy is applied to the faceplate.The PCTC module mass is 200 kg. It is clear that Scheme 2 utilizes significantly fewer components than Scheme 1; in addition, the total component weight in Scheme 2 is 37.9% less than that in Scheme 1.

Numerical calculations

Boundary conditions

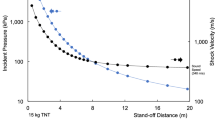

In this study, a certain type of unmanned armored vehicle was used as the research object, and explosion tests were conducted in accordance with the NATO AEP-55 standard14 at the 2 kg level. The vehicle had a total mass of 9.5 tons. The AEP-55 standard specifies that the TNT can be located anywhere on the bottom of the protective assembly, and simulating blasts at every point is an impossible task. While considering that the component scheme is symmetrical, four sample points were uniformly chosen as blast points, as shown in Fig. 3.

Explosives, such as TNT, have high energy densities and produce explosion speeds greater than 4000 m/s. During explosions, the blast waves propagate through compressed media using complex hydrodynamic reactions that are accompanied by mutual transformations of the resulting energy. The relationship between the pressure, volume, and internal energy of an explosive is presented in Eq. (1)15:

where \(\:{P}_{2}\) represents the pressure, \(\:{E}_{0}\) is the initial internal energy density, \(\:V\) is the relative volume, and \(\:A,\:B,\:{R}_{1},\:{R}_{2},\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:w\) are the material constants. The parameters for the equation of state are taken from reference15 and are given in Table 1. The MAT_HIGH_EXPLOSIVE_BURN constitutive model was used for the TNT in this study, and its parameters are listed in Table 215.

The MAT_NULL constitutive model was used for air, and the EOS_LINEAR_POLYNOMIAL equation was used as the linear equation of state. The relationship between the volume, internal energy, and pressure of the air is given in Eq. (2)16:

where \(\:{P}_{3}\) is the pressure, \(\:\mu\:\) represents the relative volume, \(\:{E}_{2}\) is the energy per unit volume, and \(\:{C}_{0}\)–\(\:{C}_{6}\) are the coefficients of the polynomial equation (\(\:{C}_{0}\) = 0.1 MPa, \(\:{C}_{1}\) = \(\:{C}_{2}\) = \(\:{C}_{3}\) = \(\:{C}_{6}\) = 0, and \(\:{C}_{4}\) = \(\:{C}_{5}\) = 0.4 MPa)16.

The soil material itself was a mixture of soil particles, air, and water. The physical parameters of its various components determined its microstructure, and thus its mechanical properties. Given that each parameter exerts its own influence, using an appropriate soil ontological model to accurately describe the dynamic response characteristics of the soil within the explosion environment is crucial when simulating the explosion impact of a shallowly-buried explosive.

The modified Mohr–Coulomb plasticity model was used to simulate the behavior of the soil mechanical properties under blast loading conditions. In the soil plasticity phase, the yield surface was defined according to Eq. (3)17:

where \(\:P\) represents the pressure, \(\:\phi\:\) is the internal friction angle of the soil, \(\:{J}_{2}\) is the second deviatoric stress invariant, \(\:C\) represents the soil cohesion, and A is the modified yield surface fitting coefficient. When A = 0, Eq. (3) represents the standard Mohr–Coulomb yield surface and \(\:K\left(\theta\:\right)\) is the equation for the deviatoric surface internal angle, \(\:\theta\:\), which is expressed by Eq. (4):

.

In Eq. (4), e represents the ratio of the triaxial tensile strength to the triaxial compressive strength. The modified Mohr–Coulomb plasticity model considers more soil mechanical properties when describing the mechanical behavior of the soil; therefore, it requires a larger number of input parameters. The parameters of the ontological soil model are shown in Table 3.

Comparison between the schemes

The dynamic response characteristics of Scheme 2’s protection module under explosion impact conditions are shown in Fig. 4. The pressure of the shock wave acting on the protection module peaked between 4 and 6 ms as shown in Fig. 4a. As shown in Fig. 2, the height of the backplate in Scheme 1 is equal to that of the crossbeam of the frame. The tube in Scheme 2 is 12 mm lower than the crossbeam. Therefore, the heights of the space available for deformation of the upper guard assembly at each of the four blast positions are different in the two schemes. The threshold value for the height of the space in which the guard assembly can be deformed is 50 mm for all the blast positions in Scheme 1. In Scheme 2, the threshold value for the height of the space in which the upper guard assembly can be deformed is 50 mm for Position 1, while it is 62 mm for the other three positions. The maximum elastic deformation of the guard assembly was obtained from simulations in which the TNT was placed at each of the four positions for both schemes, as shown in Fig. 5.

A comparison of the blast protection effects of the two schemes is discussed next. The maximum deformation was 29.4 mm and the remaining height was 20.6 mm for Scheme 1 when the explosion occurred at Position 1. Scheme 2 produced a maximum deformation of 35.8 mm and a remaining height of 14.2 mm for Position 1 as shown in Fig. 4b. The maximum deformation produced by the explosion at Position 2 was 35.4 mm for Scheme 1, while the remaining height was 14.6 mm. The maximum deformation at Position 2 for Scheme 2 was 41.7 mm, while the remaining height was 20.3 mm. The maximum deformations produced by the explosion at Position 3 were 49.7 and 60.0 mm for Schemes 1 and 2, respectively, and the remaining heights were 0.3 and 2 mm, respectively. For the explosion at Position 4, Scheme 1 produced a maximum deformation of 49.8 mm and a remaining height of 0.2 mm, while Scheme 2 produced a maximum deformation of 58.1 mm and a remaining height of 3.9 mm.

The results presented above demonstrate that the proposed PCTC module has better explosion protection capabilities than the structure in Scheme 1 despite having fewer components. Additionally, the weight of this PCTC module is 37.9% less than that of the structure in Scheme 1. However, the PCTC explosion protection performance and weight could be further optimized to obtain an optimal compromise between performance and weight.

Multi-objective optimization and experimental verification

Experimental design and agent modeling

The relationship between the design variables of a protective component and the dynamic response parameters is represented by highly nonlinear mapping. It is difficult to accurately express the functional relationship between the two for complex systems. Neural networks have strong nonlinear mapping functions that are very suitable for establishing such complex nonlinear models20. In this study, the radial basis function (RBF) neural network approximation model and the non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II (NSGA-II)21 were used to optimize the Scheme 2 design. The RBF neural network was used to construct an approximation model for the experimental design samples, then the NSGA-II was used to perform numerical optimization to obtain the optimal parameter set for the components.

Table 4 defines the design parameters. X1 represents the thickness of the PCTC faceplate, X2 is the thickness of the PCTC beam structure, X3 is the thickness of the PCTC tube, and X4 represents the diameter of the PCTC tube. The optimization objective was to minimize the residual heights, H1, H2, H3, and H4, and the mass, M, of the PCTC under four sets of operating conditions. The mathematical model for this optimization problem is presented in Eq. (5):

.

The Latin hypercube experimental design method has the advantages of high efficiency and good equalization22. It can randomly populate the space and reduce the number of iterations in the computational phase by creating a fair distribution among the design variables23,24, thereby enabling better predictions for highly nonlinear problems. A set of 120 design solutions was obtained during this study, as shown in Table 5. The entire solution set is provided in the appendix Table A1.

Parameter analysis

Using the solutions obtained from the experiment, the relationship between the design parameters and the target parameters, M, could be analyzed. The response surface plots in Fig. 6 are used to show the variation trends between the design parameters and the target parameters. These response surface plots can provide guidance for multi-objective optimization design. As shown in Fig. 7, the contributions of the design variables to the deformation and mass in the Scheme 2 design under the four sets of operating conditions were analyzed using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) method.

Figure 7 shows the contribution of each of the four design variables to component mass, and component deformation for each of the four impact conditions. As shown in Fig. 7, X1 has the greatest effect on the deformation amount at Position 1, X2 has the greatest effect on the deformation at Position 2, X3 and X4 has the greatest effect on the deformation at Position 3. The results further show that the tube has a significant impact at each position except for Position 1.

Optimization solution selection and simulation verification

The optimization of the explosion protection module performance is in contradiction to the weight optimization. The primary focus of this section is the design of the protection module weight after ensuring that the module met the protection requirements for the four explosive conditions, i.e., H1, H2, H3, and H4 ≥ 0. A compromise was made between the protection performance and the optimal thickness of the structure, which therefore made the protection module as light as possible.

The set of Pareto solutions for the target parameters is shown in Fig. 8. The optimal design was selected, and numerical calculations were performed to verify this optimized design. The results are shown in Table 6. As shown in Fig. 9, the dynamic deformation values for Scheme 2 under all four conditions met the protection requirements and were nearly consistent with the optimization results. The results show that the weight of the optimized scheme was further reduced by 9.45% from that of the initial design scheme.

Experimental verification of the optimization results

The most direct way to test whether the design results met the required specifications was to perform an experiment. The test test steps are carried out in accordance with the requirements of AEP-55. As shown in Fig. 10, a deformable aluminum strip was placed over the intersections of the beam structure and the tube before the experiment began. It was used to measure the maximum deformation of the optimized design solution during the explosion process. After attaching the protected plate, the mass distribution outlined in the optimized design scheme was laid out in conjunction with a load corresponding to that of a certain type of lightweight, high-mobility unmanned armored vehicle. Position 1 was selected as the blast location for the verification experiment. As shown in Fig. 11, the process during which the blast shock wave acted on the protection module was recorded by a high-speed camera.

The remaining height of the deformed aluminum strip corresponded to target parameter H1 in the numerical calculations. As shown in Fig. 12, the remaining height of the deformed aluminum strip was measured to be 13.8 mm after the experiment was completed. The panels were scanned in three dimensions to generate a numerical model. This plastic deformation of this numerical model was compared with that obtained from the simulation. As shown in Fig. 12, the amount of plastic deformation of the protection assembly obtained from the panel scan was 9.76 mm, while the calculated deformation value was approximately 10 mm. The results indicate that the experimental data agreed well with the calculated data.

Conclusions

This paper proposed a protection module, PCTC, for lightweight and high-mobility unmanned armored vehicles. The protection performance of this module was numerically analyzed and the weights of a traditional design scheme and this module were compared. In addition, while considering the low weight requirements of lightweight, high-mobility unmanned armored vehicles, multi-objective optimization design was conducted to decrease the weight and improve the protection performance of the protection module. This study produced the following three primary conclusions.

-

(1)

The weight of the proposed PCTC protection module was 37.9% lower than that of a conventional protective component design solution. In addition, the PCTC module, which contained fewer components than traditional protective assemblies, could be used for lightweight, high-mobility armored vehicles.

-

(2)

PCTC protection modules provided better protection against multi-explosive conditions than conventional protective components used in armored vehicles.

-

(3)

During the multi-objective optimization design performed during this study, 120 solutions were obtained by experimental design and numerical calculation. Optimized design solutions were then selected to further improve the weight and performance of the protection module.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Li, M. et al. Application of Six Sigma method in optimisation design of vehicle anti-explosion components. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 237 (5), 883–894. (2023).

Johnson, T. E. & Basudhar, A. A metamodel-based shape optimization approach for shallow-buried blast-loaded flexible underbody targets. Int. J. Impact Eng. 75, 229–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2014.08.010 (2015).

Rigby, S. E. et al. Experimental measurement of specific impulse distribution and transient deformation of plates subjected to near-field explosive blasts. Exp. Mech. 59, 163–178 (2019).

Langdon, G. S., Curry, A. & Siddiqui, A. Improving the impulse transfer and response characteristics of explosion loaded compound angle V-plates. Thin-Walled Struct. 148, 106609 (2020).

Nayak, S. K. et al. Process for design optimization of honeycomb core sandwich panels for blast load mitigation. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 47, 749–763 (2013).

Nayak, S. K. Optimization of Honeycomb Core Sandwich Panel To Mitigate the Effects of Air Blast loading (Diss. The Pennsylvania State University, 2010).

Gunes, R. et al. Experimental investigation of the low-velocity impact response of sandwich plates with functionally graded core. J. Compos. Mater. 54 (24), 3571–3593 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Dynamic response of double-layer rectangular sandwich plates with metal foam cores subjected to blast loading. Int. J. Impact Eng. 122, 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2018.08.016 (2018).

Shen, J. et al. Experiments on curved sandwich panels under blast loading. Int. J. Impact Eng. 37 (9), 960–970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2010.03.002 (2010).

Jing, L. et al. An experimental study of the dynamic response of cylindrical sandwich shells with metallic foam cores subjected to blast loading. Int. J. Impact Eng. 71, 60–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2014.03.009 (2014).

Hassan, M. Z. et al. The influence of core density on the blast resistance of foam-based sandwich structures. Int. J. Impact Eng. 50, 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2012.06.009 (2012).

Hause, T. & Librescu, L. Dynamic response of anisotropic sandwich flat panels to explosive pressure pulses. Int. J. Impact Eng. 31 (5), 607–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2004.01.002 (2005).

Lan, X. et al. A comparative study of blast resistance of cylindrical sandwich panels with aluminum foam and auxetic honeycomb cores. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 87, 37–47 (2019).

N.A.T.O.: Procedures for evaluating the protection level of logistic and light armoured vehicles-mine threat, 1st edn. Report AEP-55, vol. 2. Allied Engineering Publication (2006).

Lee, E., Finger, M. & Collins, W. JWL equation of state coefficients for high explosives. Lawrence Livermore National Lab.(LLNL), Livermore, CA (United States), https://doi.org/10.2172/4479737 (1973).

Hallquist, J. LS-DYNA Keyword User’s Manual, Version: R10.0. Livermore, California (2017).

Lewis, B. A. & MANUAL FOR LS-DYNA SOIL MATERIAL MODEL 147 (Mathematical Models, 2004).

Lee, W. Y. Numerical Modeling of blast-induced liquefaction[M] (Brigham Young University, 2006).

Zhou, Q. & Liu, S. Mechanisms of diverting out-of-plane impact to transverse response in plate structures. Int. J. Impact Eng. 133, 103346 (2019).

Rajeev, S. & Krishnamoorthy, C. S. Genetic algorithm–based methodology for design optimization of reinforced concrete frames. Comput.-Aid. Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 13 (1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/0885-9507.00086 (1998).

Wang, Y. C. & Chen, T. Adapted techniques of explainable artificial intelligence for explaining genetic algorithms on the example of job scheduling. Expert Syst. Appl. 237, 121369 (2024).

Viana, F. A. C., Venter, G. & Balabanov, V. An algorithm for fast optimal Latin hypercube design of experiments. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 82 (2), 135–156 (2010).

Karthik, A. et al. A novel MOGA approach for power saving strategy and optimization of maximum temperature and maximum pressure for liquid cooling type battery thermal management system. Int. J. Green Energy. 18 (1), 80–89 (2021).

Navid, A., Khalilarya, S. & Abbasi, M. Diesel engine optimization with multi-objective performance characteristics by non-evolutionary Nelder-Mead algorithm: Sobol sequence and Latin hypercube sampling methods comparison in DoE process. Fuel 228, 349–367 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Open Fund of Chinese Scholar Tree Ridge State Key Laboratory, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 52272437 and 52272370). The authors also thank LetPub (www.letpub.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mingxing Li: manuscript,Research Ethics, Reporting standards and availability of data, materials, code and protocols, Image integrity and standardsXianhui Wang: statistical expertise, obtaining funding, administrative, technical or material support, and supervisioHaitao Liu: Project Support, conception and design of the study, data collectionXiaowang Sun: writing the manuscript or providing critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content, obtaining funding Song Binwen: conception and design of the study, data collection Tiaoqi Fu: analysis and interpretation of the data Tuzao Yao: data collection.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, M., Wang, X., Liu, H. et al. MultiObjective optimization of the design of a protective components to chassis protection module for unmanned armored vehicles. Sci Rep 15, 6975 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91632-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91632-6