Abstract

Insoluble iron deposits often exist as iron oxide nanoparticles in protein aggregates, impaired ferritin, or activated microglia and have been implicated as major causes of neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. However, no crucial evidence has been reported to support the therapeutic effects of current iron chelators on the deposition of various molecular forms of insoluble iron. We investigated the therapeutic effect of carbon ion stimulation (CIS) via a transmission beam on insoluble iron deposits, iron inclusion bodies, and the associated biological response in 5xFAD AD mouse brains. Compared with no treatment, CIS dose-dependently induced a 33–60% reduction in the amount of ferrous-containing iron species and associated inclusion bodies in the brains of AD mice. CIS induced considerable neuroinflammation downregulation and, conversely, anti-inflammatory upregulation, which was associated with improved memory and enhanced hippocampal neurogenesis. In conclusion, our results suggest that the effective degradation of insoluble iron deposits in combination with pathogenic inclusion bodies promotes AD-modifying properties and offers a potential CIS treatment option for AD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Protein binding renders magnetite in a redox-active reduced state, which produces toxicity to iron deposit-protein aggregates1,2,3,4. The interaction of the Aβ protein with ferritin induces the release of ferrous magnetite from ferritin and the formation of pathogenic ferritin, which contains ferrous magnetite-amyloid-ferritin aggregates3,4,5,6. Microglial activation is triggered by direct glial uptake of pathogenic ferritin6,7 or Aβ plaque-infiltrating microglia8, which can contain ferrous magnetite1,9,10. An inflammatory cascade catalyzes microglial ferroptosis, ferroptosis-mediated neuronal or astrocyte loss, and the induction of neurotoxic reactive astrocytes11,12,13,14,15. This subsequently stimulates multiple signaling pathways to induce tauopathy and generate additional reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cytokines, resulting in the spread of oxidative damage in Alzheimer’s disease (AD)16,17. The significance of nanoparticles for insoluble iron deposition in terms of potential therapeutic application, including as iron chelators, has not been well recognized in the medical field.

We propose that redox-active iron oxide deposits, involved in the neuroinflammatory response and distinct from cellular labile iron ions, can exist in the form of insoluble protein aggregates, pathogenic ferritin aggregates, or iron-laden microglia. Furthermore, if not eliminated, redox-active iron deposits are continuously neurotoxic via neuroinflammation induction and should be targeted to achieve disease-modifying effects while preventing further neuronal damage13,15. Our prior work on proton stimulation treatment in an AD mouse model demonstrated disrupted and reduced iron deposition in Aβ plaques and improved cognitive impairment18. The present study explored whether disrupting redox-toxic iron deposits and protein aggregates by carbon beam transmission influenced the neuroinflammatory response in an AD mouse model.

Methods

Animals and study design

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Tsukuba (protocols #210097 and #21–193), and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the University’s Regulations for Animal Experiments.

Male and female AD 5xFAD transgenic (Tg) mice on a C57BL/6J background (5xFAD-C57BL/6J), as well as two female and two male nontransgenic (non-Tg) mice of the same background, were used in this study. Frozen embryos of 5xFAD Tg mice, initially obtained by crossbreeding B6. Cg-Tg (APPSwFlLon, PSEN1*M146L*L286V) 6799Vas/Mm hemizygous males (line 034848-JAX, The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) with non-Tg C57BL/6J females (Charles River Labs Japan, Inc., Yokohama, Japan) were kindly provided by Dr. Yu Hayashi from the International Institute for Integrative Sleep Medicine (WPI-IIIS) of the University of Tsukuba. These data were obtained after the Members of the Mutant Mouse Resource and Research Center (MMRRC) collaboration records were updated and the required legal agreement (COU) was submitted and approved by the Jackson Laboratory. The in vitro fertilization (IVF) procedure using 5xFAD Tg embryos was conducted at the Laboratory Animal Resource Center of the University of Tsukuba. DNA was extracted from mouse biological material using the Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany), and PCR was performed using corresponding primers specific for the mutated genetic sequence (Fasmac Co. Ltd., Atsugi, Japan). Male Tg mice were crossbred with non-Tg C57BL/6J females to produce additional stocks. Male and female mice in the Tg and non-Tg groups were housed separately under a 12/12 h light/dark cycle (with lights on at 9 A.M.) under controlled temperature (23.5 ± 2.0 °C) and humidity (51.0 ± 10.0%) conditions with free access to water and food. Mice were housed at an SP-grade facility in solid plastic cages (CLEA Japan, Inc., Shizuoka, Japan) with sterilized wood-chip bedding (Sankyo Labo Service Corp., Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

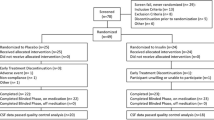

Animal study was designed in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. Two mouse cohorts of different ages were created at the time of irradiation. The first cohort of mice (4 months cohort, nWT = 5, n5xFAD = 15, and irradiated at the age of 4 months) was used to evaluate the disruption of iron deposits and inclusion bodies after CIS as a potential preventative treatment for early-stage of AD. The second cohort of mice (10 months cohort, nWT = 10, n5xFAD = 11) was irradiated at the age of 10 months and sacrificed prior to the behavioral task at the age of 11months, one month after CIS to evaluate the immunohistology and inflammatory response while curing pathological burdens and improving cognitive function for relatively late stage of AD. The CIS irradiated groups were compared with untreated 5xFAD or wild-type (WT) control groups. Male and female mice were randomly assigned to specific experimental groups. The mice were transported to the irradiation facility by a specialized vehicle with controlled temperature and humidity and kept there for at least 1 week before the experiments.

Scientific rationale of CIS treatment on magnetite

Carbon transmission beams in CIS treatment interact quasi-selectively (See Fig. 1) with iron oxide or metallic nanoparticles over tissue elements to emit bursts of low-energy electrons (LEE) from the iron nanoparticle surface via Auger cascades and a nano-atomic cluster-based interatomic Coulomb decay process19,20. LEEs disrupt iron-protein bonds and degrade the protein matrix through Fenton effects, leading to depletion of iron deposition and iron inclusion bodies like amyloid plaques and dystrophic microglia2,19.

Schematic diagram of carbon ion stimulation treatment with a pristine Bragg peak behind the brain of a carbon transmission beam; the Bragg peak was placed outside the brain by a high-energy carbon beam compared with the depth of the mouse head (left panel). Low-energy electron (LEE) emission occurs as a dose enhancement factor from CIS-treated magnetite (Fe3O4) in AD protein aggregates or activated microglia via Auger cascades and the interatomic Coulomb decay path. The potential carbon fluence during the transmission of brain tissues containing Aβ plaques with magnetite abruptly decays to zero at the Bragg peak position, resulting in the deposition of all energy, but the plateau dose (PD) is absorbed by the tissue along the beam path, enabling quasi selective stimulation of intraplaque magnetite with a comparable Bragg peak dose (BPD), which is 5–10 times greater than the PD.

CIS treatment

CIS was performed at HIMAC (Chiba, Japan). Mice were anesthetized prior to CIS treatment by an intraperitoneal injection of 10 mL/kg of a ketamine + xylazine mixture (100 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg in saline, respectively), placed on a sample holder for whole-brain irradiation, and irradiated with a transmitted beam of pristine carbon with a collimator. The control group was not treated. The irradiated mice were returned to the animal housing room of the heavy ion facility and kept in individual cages for 3–10 days. The whole brain was irradiated via carbon beam transmission with a pristine Bragg peak behind the head19,20,21,22, as shown in Fig. 1. The irradiation energy was 400 MeV, which was sufficiently high to transmit through the mouse head. The single entrance dose was either 2–4 Gy, as measured by an ionic chamber (PTW) at the frontal surface of the sample. The dose rate was 0.02 Gy/s. The doses were selected based on safety thresholds determined in our prior work on the same type of AD mouse19.

Histological analysis

Mice in the 4-month cohort were sacrificed by an overdose of pentobarbital IP (120 mg/kg) on the 7th day after treatment. The brains were harvested, postfixed with fresh fixative (PFA) overnight, and subsequently placed in PBS, after which the brain tissue was thoroughly washed with PBS prior to sectioning. The fixed specimens of mouse brain tissues were placed in a plastic cassette for specimen production, and the water in the specimens was replaced with alcohol and then with xylene. The specimens were finally embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 10-µm intervals, and mounted on glass slides. Disruption of iron deposition and the Aβ plaque burden in the CIS-treated mice were determined via histochemical analysis of four different tissue sections, including the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus, and were compared with those in the control group. The sections were stained with acidified 1% (wt/vol) potassium ferricyanide via Turnbull staining for ferrous cations (Fe2+) or with 0.2% Congo red in 50% alcohol using modified Highman’s Congo Red staining for amyloid plaques23. The sections were stained for approximately 10 min for Congo red staining, washed to remove nonspecific tissue deposits from the Congo, stained with hematoxylin for 2 min, and examined under a microscope. The number of stained plaques per section was determined using automated analysis as described previously19 and averaged per section or mouse. ImageJ software, available at https://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/, was used to analyze amyloid plaques and Fe2+ particles. To determine the number of Aβ plaques or the iron load, data were collected, analyzed at ×200 magnification, and subjected to statistical analysis.

Behavioral task

Twenty-two mice in the 10-month cohort were obtained and assigned to six experimental groups. Three of the groups contained WT mice (n = 10), including untreated (n = 2; all male), 2 Gy CIS (n = 4; two female and two male), and 4 Gy CIS (n = 4; two female and two male) mice. Furthermore, three of the groups contained heterozygous 5xFAD AD mice (n = 12), namely, untreated (n = 4; all male), 2 Gy CIS (n = 4; two females and two males), and 4 Gy-CIS (n = 4; two females and two males) mice.

The NOR test24 was performed 3 days prior to CIS and 1 month after treatment. Each mouse was presented with two similar objects during the first session, and then one of the two objects was replaced with a new object during the second session. The amount of time spent exploring the new object was used as an index of memory recognition and was calculated as the difference in the ability of the mouse to distinguish between objects. Typically, a normal mouse pays more attention to a novel object24.

Western blot analysis

Twelve mice in the 10-month cohort were assigned to four experimental groups: untreated WT (n = 3; one female and two male), 4 Gy CIS WT (n = 3; two female and one male), untreated 5xFAD (n = 3; all male), and 4 Gy CIS 5xFAD (n = 3; two female and one male) mice. The animals were sacrificed using the physiological saline cardiac perfusion method. The brains were extracted and cut into two haploids, using the right for IHC and the left for western blot. The right haploids were fixed in 4% PFA solution overnight, transferred to 30% sucrose in PBS, and, after sinking, transformed into frozen optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT) blocks. Subsequently, thin Sect. (25 μm) were produced. The remaining haploids were sonicated and lysed with RIPA buffer for western blotting. Mouse brain tissue was dissected on ice and homogenized in a lysis buffer (Biosesang, R2002) prior to supplementation with protease inhibitors (1 µg/ml protease inhibitor cocktail X100, 1 µg/ml phosphate inhibitor cocktail X100, and 1 mM PMSF). The protein concentration was subsequently quantified using the Bradford assay25. Protein samples (20 µg) were separated via 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (120 V, 90 min) and transferred (100 V, 90 min) to nitrocellulose membranes26. The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in TBST for 1 h and then incubated with the following primary antibodies in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 4 °C for 24–48 h according to the following dilution ratios: amyloid-beta (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA; SC-53822, 1:500); APP (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA; 14-9749-82, 2.5 µg/ml); GFAP (BD Biosciences, Dickinson, ND, USA; BD-556328, 5 µg/ml); BACE1 (Invitrogen, PA5-19952, 1:1000); Iba-1 (Abcam, Cambridge, CAM, UK; AB178846, 1:2000); TGF-beta (Invitrogen, MA1-21595, 1:500); TNF-alpha (Santa Cruz, SC-52746, 1:500); IL-1beta (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA; CS2022, 1:1000); glutathione peroxidase 4 GPX4 (Santa Cruz, SC-166570, 1:1000); and DCX (Santa Cruz, SC-271390, 1: After being washed three times with Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20, the blots were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP; anti-goat mouse or anti-goat rabbit HRP; Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA; ADI-SAB-100-J; 1:2000; or AD-SAB-300-J, 1:2000. Antigen-antibody interactions on the membrane were detected by a ChemiDoc imaging system (Davinch-K, Seoul, Republic of Korea, CAS-400SM) using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MS, USA, 34095). The protein concentration was quantified utilizing the ImageJ program. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA. Differences were considered to be statistically significant when p values were lower than 0.05 (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Immunohistochemistry

Doublecortin (DCX) immunohistochemical staining was performed to study neurogenesis. One month after CIS treatment, the mice were anesthetized with ketamine (80–100 mg/kg) and xylazine (5–10 mg/kg) and then transcardially perfused with 0.9% ice-cold saline. The brains were harvested and postfixed in 4% PFA. The samples were then cryoprotected in 30% sucrose solution overnight at 4°C, embedded in OCT compound on dry ice, and finally stored at -80°C until further use. Coronal Sect. (25 µm) were obtained with a cryostat (Leica, Germany). For immunohistochemistry, four to five animals were chosen randomly per group. Three sections per mouse were used for intensity-scanning analysis. Free-floating sections recovered from the glycol antifreeze solution were washed three times in 0.1 M Tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 10 min and then quenched with 3% H2O2 and 10% MeOH in 0.1 M TBS for 10 min. The sections were then washed three times in 1× TBS for 10 min each, blocked in 5% normal horse serum (NHS) containing 0.05% Tween-20 and 0.05% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature, and incubated with a primary antibody (goat polyclonal anti-DCX) (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC8066) in 5% blocking solution for 48 h at 4°C. Primary antibody treatment was followed by treatment with a secondary antibody (biotinylated horse anti-goat IgG) (1:100; Vector, USA) in a 2% blocking solution for 2 h at room temperature. The sections were washed three times with 0.1 M TBS for 10 min each and incubated in Vectastain Elite avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) solution for 1 h at room temperature. The peroxidase reaction products were visualized by incubating the sections in a solution containing 0.022% 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Aldrich, Gillingham, UK) for 2–3 min. Subsequently, the brain sections were mounted onto 2% gelatin-coated microscope slides. All the slides were then covered with coverslips and stored at 4 °C until they were analyzed via confocal microscopy under identical conditions. Light microscopy was performed on a pannoramic platform (3D HITECH, Budapest, Hungary) to visualize cells in the granule cell layer and the hilus of the hippocampal dentate gyrus. The cells were manually quantified using the ImageJ program (version 1.8.0, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Microglial cellular uptake of Aβ1−42-Fe3O4 fibrils and CIS treatment

To better understand the effect of CIS on microglial iron deposition, BV2 microglial cells were treated with Aβ1−42-Fe3O4 fibrils and CIS irradiation. Fibrils were prepared as previously described19. Briefly, monomeric synthetic Aβ1–42 peptide (ANYGEN, GwangJu, Korea, AGP-8338) was dissolved in 0.1 M NaOH to obtain a 220 MA stock solution. This stock solution was left standing for 30 min to ensure complete peptide dissolution prior to mixing with the 80 g/mL magnetite (Sigma‒Aldrich; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) solution. Magnetite solutions containing thioflavin T (Tf-T) were incubated with shaking at 37◦C for 144 h, and the fibril formation was checked via Tf-T fluorescence. During cell culture and treatment, BV2 microglia were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 1% antibiotic-antimitotic agents at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. The cells were treated with Aβ1−42-Fe3O4 fibrils at a final concentration of 2.5 µM 12 h prior to CIS treatment. Cells exposed to media containing 1X PBS were used as the vehicle-treated control group.

The cells were detached 12 h after CIS treatment and transferred to poly-l-lysine-coated 24-well plates on coverslips. After the cells were incubated for 24 h, the coverslips were washed with distilled water and then immersed in potassium ferricyanide staining solution for 1 h. The coverslips were washed in 1% acetic acid and counterstained with nuclear-fast red for 5 min, followed by mounting with a prolonged mounting solution (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MS, USA, P36930).

Pretreatment of SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells with Aβ

Monomeric synthetic Aβ42 was obtained from Anygen (Daejeon, Korea). SH-SY5Y cells (ATCC, CRL-2266) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C in an atmosphere with 5% CO2. A total of 3 × 106 cells were seeded in each well of a 96-well plate and incubated overnight with 100 µM Aβ. Iron enhancement was measured in the treated cells by Turnbull staining. CIS at 2–4 Gy was applied to a flask containing SH-SY5Y cells pretreated with Aβ.

Cell viability assay

The cell viability assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo, Rockville, MD, USA). Twenty-four hours postirradiation, the cells were detached from the flask. A total of 2 × 104 cells in a volume of 200 µl were seeded into the wells of a 96-well plate and incubated at 37 °C. After 24 h, the medium was replaced with 200 µL of fresh medium, followed by adding 10 µL of CCK-8 solution and incubating at 37 °C for 2 h. The optical density representing cell viability was measured at 450 nm by AMR-100 spectrophotometry (Allsheng, Hangzhou, China). The experiments were performed independently in triplicate.

Statistics

The data are presented as the means ± SEMs. One-way ANOVA with post hoc tests was performed using SAS software (SAS Institute, NC, USA). Student’s t-test was utilized to compare differences between the two groups. Differences were statistically significant if p < 0.05.

Results

CIS-depleted iron deposition and inclusion bodies

Turnbull staining analysis revealed various features of iron deposition, suggesting iron deposition in Aβ plaques (long arrow), ferritin (unfilled arrowhead), and microglia (filled arrowhead) in both the hippocampus (A) and the entorhinal cortex (B–D) of untreated 5xFAD mice. Traces of iron deposition surrounding plaques suggested the presence of microglial iron and impaired ferritin aggregation (B) but were not confirmed via antibody-based histopathology. In DAB-enhanced Turnbull plus H&E staining analysis of 3xTG AD mouse brain, various iron inclusion bodies were distinguished based on morphologies of iron distribution, including Aβ plaques (long arrow), neurofibrillary tangle (short angle), and microglia (filled arrowhead) (E).

Turnbull staining analysis demonstrated various features of iron deposition in 5xFAD mice, as shown in Fig. 2A-D, suggesting the presence of intraplaque iron foci, ferritin, and microglial iron, as indicated in Fig. 3A. A dose-dependent reduction in iron deposition was detected in CIS-treated 5xFAD mice compared with untreated control mice, as shown in Fig. 3A and B. Multiple traces of iron deposition were found around a large Aβ plaque, as shown in Fig. 2B. Since microglia were often found in surrounding Aβ plaque8,9,10,27, these iron traces suggest that they may be associated with microglia, accompanied by Aβ fibrils and ferritin aggregates.

Since iron binds Aβ or tau protein specifically, the iron distribution in extracellular Aβ-plaque or axonal neurofibrillary tangle often gives distinctive features from staining as an iron inclusion body, as demonstrated in Fig. 2E. Moreover, microglia are relatively smaller than plaque, with an overall globular shape in histochemical iron staining due to the cellular characteristics of the inclusion body.

Results of Turnbull (A,B) and Congo red (C,D) staining of CIS-treated AD mice showing a reduction in the number and size of Turnbull-positive iron deposits (amyloid plaque + ferritin + microglia) and Aβ plaques in a dose-dependent manner compared with those in the untreated control group, decrease in plaque size as shown in enlarged square panels. The untreated control presented various molecular forms of iron deposition compared with the WT control, in which only normal ferritin iron was shown. Congo red (CR) analysis revealed extracellular CR + plaques (arrow) and intracellularly accumulated CR + amyloid fibrils, suggesting that either Aβ plaques infiltrated microglia (unfilled arrowhead) or immature neuronal amyloid fibrils. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01. scale bar: 20 μm.

Both extracellular and intracellular Congo red-positive (CR+) plaques were visualized in 5xFAD mice, as shown in Fig. 3C, suggesting that intracellular CR + existed as either immature amyloid fibrils or plaque-infiltrating microglia. The number and size of CR + plaques were reduced dose-dependent compared with those in untreated control mice, as demonstrated in Fig. 3D. Histological analysis indicated a dose-dependent reduction in iron deposition and inclusion bodies (Fig. 3B, D). An analysis of designated sections from each mouse (a total of four sections per mouse) revealed that, 7 days after CIS, the average number of plaques or ferrous iron foci per mouse was reduced by 48% or 57%, respectively, in CIS-treated mice compared with untreated mice.

CIS-induced neuroinflammation downregulation

β-amyloid, Human-APP (h-APP), precursor APP, and β-secretase (BACE-1) were reduced by 45–60% after a single CIS treatment compared with those in untreated 5xFAD AD mice and were correlated with CIS-derived depletion of ferrous iron and plaques, as shown in Fig. 4A–C. CIS may also alleviate neuroinflammation by directly affecting pathophysiological mechanisms at the stage of activated microglia by targeting microglial iron9,28. The expression of Iba-1, a marker of activated microglia, was significantly greater in untreated AD mice than in wild-type control mice and was markedly lower in treated AD mice (p < 0.01), as shown in Fig. 4E. The expression of GFAP, a marker of reactive astrocytes, was also significantly decreased (p < 0.05), as shown in Fig. 4A and D.

Results of electrophoretic running (A) and Western blot analyses for hAPP (B) and β-secretase (C); GFAP for reactive astrocytes (D); lba-1 for activated microglia (E). All the decreases in inflammatory response factors (D,E) correlated with the reduction in amyloid pathology (B,C) after CIS treatment, suggesting CIS-driven depletion of iron deposition and associated inclusion bodies, such as amyloid plaques.

We evaluated the impact of CIS on the microglia-driven inflammatory response to determine the role of iron deposition in neuroinflammation in AD. The levels of TNF-α and IL-1β, cytokines typically released from proinflammatory microglia (with the M1 phenotype), were greater in untreated AD mice than in WT control mice and were greatly lower (p < 0.01) in CIS-treated AD mice, as shown in Fig. 5. Furthermore, the cytokine TGF-β, which is typically released from anti-inflammatory microglia (with the M2 phenotype), was increased 1 month later in treated AD mice compared with untreated AD mice (p < 0.05).

WT-aged mice were not significantly different between the untreated and CIS-treated groups. With normal aging, microglia develop a more inflammatory phenotype, thereby showing increased proinflammatory cytokines in the brain and resulting in slightly increased lba-1 even after CIS treatment, suggesting potential iron release from sequestrating bodies or iron-independent proinflammatory progress. CIS-driven depletion of age-related iron accumulation might have enhanced the anti-inflammatory phenotype by increasing the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as TGF-β, as shown in Fig. 5A–D.

In vitro CIS treatment of iron-laden microglia depleted microglial iron, as shown in Fig. 5E.

Results of Western blot analysis (A) used to measure cytokine release by anti-inflammatory microglia, TGF-β (B), TNF-α (C), and IL-1β (D) to determine the proinflammatory response, suggesting that the microglial phenotype changed from proinflammatory to anti-inflammatory one month after CIS treatment. Turnbull staining of microglial BV2 cells treated with Aβ-Fe3O4 fibrils revealed depletion of Aβ-Fe3O4 fibrils within BV2 cells after CIS treatment (E), suggesting that iron is released in BV2 cells upon disruption of Aβ-Fe3O4 fibrils or subsequent microglial ferroptosis.

CIS induced the restoration of hippocampal neurogenesis and improved impaired cognitive function

To determine the effects of CIS on neurogenesis, the characteristics of CIS-AD mice were compared to those of both WT mice and untreated control mice. DCX expression was markedly lower in untreated AD mice than in WT control mice and was significantly greater in CIS-treated AD mice (Fig. 6A-D); this pattern was consistently visualized in the granular cell layer of the dentate gyrus (DG), as shown in the IHC data in Fig. 6E. There were approximately two times more DCX-positive cells (1454 ± 39, P = 0.009) in the CIS-treated mice than in the untreated AD mice (Fig. 6A-D). Furthermore, we determined the degree of neurogenesis deficiency in the DG of AD hippocampi compared to that in age-matched WT brains (Fig. 6E). There were significantly fewer DCX-positive cells in the hippocampi of AD control mice than in those of aged-matched WT mice (Fig. 6E). There were 577 ± 45 DCX + cells in the hippocampi of AD control mice. In contrast, there was a marked decrease in the number of DCX + cells in the hippocampi of WT mice (p < 0.001) (Fig. 6E).

GPX4, an antioxidant defense enzyme, repairs lipid oxidative damage and is a leading ferroptosis inhibitor in live cells29. The expression of GPX4, a marker of ferroptosis, was enhanced in untreated AD mice due to the need to repair iron deposition-mediated lipid oxidative damage but was significantly decreased in CIS-treated AD mice by reduced antioxidant demand upon depletion of pathological burdens. This repairment was also potentially supported by phenotype change to cell-repairing anti-inflammatory microglia as evidenced by enhanced TGF-β after CIS.

Results of Neurogenesis and Ferroptosis According to the Western blot (A: electrophoretic examination, B: GPX4, C: DCX) and IHC (D: DCX + cell counting, E: IHC microscopic view) analyses for the various groups. DCX, a marker of adult neurogenesis, was markedly lower in 5xFAD AD mice than in WT control mice and was restored in CIS-treated mice (p < 0.05). This observation was correlated with enhanced DCX expression in the granular cell layer of the DG in the hippocampus (E). This restoration of neurogenesis is correlated with the control of neuroinflammation and ferroptosis (A), which provides a neuronal environment conducive to the regeneration of neurons by inhibiting neuronal damage (B) and facilitating neuronal growth.

To examine memory improvement after CIS treatment, NOR behavioral tests were performed on the following mouse groups: untreated WT (10 months, n = 2), WT-post-CIS 2 Gy (n = 4), WT-post-CIS 4 Gy (n = 4), untreated 5xFAD (10 months, n = 4), 5xFAD + CIS 2 Gy (n = 3), and 5xFAD + CIS 4 Gy (n = 4). Animals were tested using memory behavioral tasks, and postmortem measurements of pathological markers were obtained. CIS treatment was performed 4 weeks prior to the post-CIS behavioral test. The 4-week period was chosen based on the results of our prior work19, which showed that at least 3–4 weeks were required to improve cognitive function after proton stimulation targeting intraplaque magnetite. During the NOR test, prior to CIS treatment (pre-CIS), all the AD mice exhibited shorter latencies to complete the novel object recognition test than the WT normal mice (Fig. 7). On average, CIS-treated mice (CIS 2 Gy and 4 Gy) spent relatively longer periods of time on the novel object than did the pre-CIS mice (p < 0.001), yielding a high discrepancy index (Fig. 7). The time spent by the CIS-treated WT mice in novel object recognition tasks differed significantly from that spent by the untreated WT-control mice.

The results of the NOR test for the behavioral task showed that the discrepancy factor was dose-dependent, indicating that, compared with untreated 5xFAD AD mice, the time spent by mice on the new object was increased in both the WT controls with normal cognitive function and the CIS-treated mice. Interestingly, this memory improvement occurred in the CIS-treated age-matched (10-month) WT controls.

Effect of CIS treatment on Aβ-pretreated SH-SY5Y cells

We investigated the effect of Aβ-ferritin-mediated magnetite release on Aβ-pretreated neuroblastoma cells. Turnbull analysis revealed a remarkable twofold increase in the level of intracellular ferrous iron after Aβ treatment compared with that in untreated control cells, as shown in Fig. 8A.

The cytotoxicity of CIS-treated cells was positively correlated with that of ferrous iron species, suggesting that Aβ pretreatment induced magnetite release, as shown in Fig. 8B.

Discussion

Neuronal death is a late-phase event and represents a therapeutically irreversible state in AD. Brain inflammation occurs before neurodegeneration during AD pathogenesis, and targeting inflammatory mechanisms may reverse the process of disease progression30. CIS treatment reversed neurotoxic insoluble iron deposition and the iron-bound plaque matrix of Aβ plaques or pathogenic ferritin by carbon ion-driven electron emission from protein-bound magnetite. The underlying mechanism involves breaking the bond between iron and proteins, transforming ferrous irons into ferric irons, and degrading the protein matrix, as demonstrated in our prior proof-of-concept studies2,19. Correlated dose-dependent depletion of iron deposition and Aβ-plaque was demonstrated by Turnbull histological analysis in PS19 or CIS treated mouse brain. WB data of Iba-1 depletion at 4 Gy suggest implicit disruption of microglial iron deposition. Moreover, Turnbull counting analysis contains intraplaque iron plus microglial iron deposition foci, suggesting dose-dependent depletion of iron deposition. For a given dose, the amount of iron deposition may determine the CIS-driven microglial fate, in either potential alteration of inflammatory phenotype as a still viable cell or depletion. Thus, higher dose may induce preferred depletion of microglial activation. Further, in vitro cellular study is required to determine optimum dose for inducing CIS-mediated change of microglial phenotype. Turnbull staining showed that the iron features present in untreated AD control mice or Aβ-Fe3O4 fibril-laden microglia were strongly reduced or absent in CIS-treated mice or microglia, corroborating the phenotypic change or ferroptosis of activated microglia depending on the amount of microglial iron.

Normal healthy ferritin contains ferric iron ferrihydrite, but pathological ferritin in AD involves magnetite6,10,31 and may form complex plaques with magnetite release when interacting with Aβ3,4,6,10,17 or activated microglia32. These ferritins are often distributed in surrounding Aβ plaques, as shown in Fig. 2B, and are regarded as potential sources of magnetite in AD brains10,30. Activated microglia infiltrating Aβ plaques and phagocytosing pathogenic ferritin are typical neuroinflammation features32. Protein aggregates, iron-sequestering ferritin, and activated microglia commonly use ferrous magnetite as a source of ferroptosis in adjacent neurons or microglia. Therefore, inflammatory response cascades are activated upon iron deposition in pathogenic lesions, as evidenced by the correlated increase in the expression of lba-1, GPX4, and GFAP shown in Fig. 4, and microglia-driven neuroinflammation has been regarded as a major cause or a bridge for the spread of neuronal damage and cognitive impairment. CIS treatment depleted these molecular forms of protein-bound iron, as shown in Figs. 2 and 3. Thus, its therapeutic effects potentially occur at multiple stages of neuroinflammatory cascades, as depicted in Fig. 9.

The depletion of neurotoxic iron deposits and related molecular forms reduced both Aβ pathologies and iron-associated ferroptosis and microglial activation, which was evident from the downregulation of APP, beta-secretase (BACE1), GPX4, lba-1, and GFAP at one month post-CIS treatment. Reduced APP and beta-secretase (BACE1) expression may represent a decreased physiological demand for amyloid-based iron sequestration or export upon CIS-mediated depletion of iron deposition one month after CIS treatment. Moreover, TGF-β expression was elevated, whereas IL-1β and TNF-α expression was reduced, suggesting a proinflammatory to anti-inflammatory microglial phenotype change.

Since activated microglia induce severe reactive astrocytes in the inflammatory response cascade, as suggested by the concomitant increase in the expression of lba-1 and GFAP in untreated 5xFAD mice (Fig. 4), removing or changing the phenotype of activated microglia is an important therapeutic goal for blocking reactive astrocytes that induce neuronal damage33,34. The CIS-driven reduction in activated microglia precluded the induction of reactive astrocytes, which is evident from the decrease in GFAP, suggesting that reactive astrocytes were downregulated. Blocking the generation of neurotoxic reactive astrocytes is critical for suppressing tau spread while preventing neuronal damage32,33. Downregulated glial responses indicate the cessation of further neuronal damage and provide a better environment for the restoration of neurogenesis. Therefore, inhibiting reactive astrocytes is beneficial for reversing cognitive decline in AD patients15,35. Impaired hippocampal neurogenesis in 5xFAD mice may be related to increased Aβ deposition and cognitive dysfunction36,37,38. The enhanced hippocampal neurogenesis and correlated NOR task-based memory improvements indicated a neurogenic effect of CIS treatment, which may be ascribed either to crosstalk between neurogenic signals and downregulated Aβ-related deposition39 or to CIS-driven induction of the anti-inflammatory effect. The increase in TGF-β release after CIS treatment suggested an alteration into the anti-inflammatory microglial phase and potentially promoted nerve growth and neurotropic factors secretion40. Microglia are innate immune cells that play a key role in the early anti-inflammatory response by removing amyloid deposits and damaged neurons through regulated phagocytosis. However, chronic iron accumulation in the AD brain damages microglial function. Microglial uptake of non-transferrin binding iron leads to activated dystrophic microglia41,42 due to following insoluble iron deposition from ferritin-released iron by infiltrated Aβ plaque43,44,45. Iron depositions trigger further microglial ferroptosis12,13, which significantly exacerbates disease progression and spreads neuronal loss and white matter injury in Alzheimer’s disease. Thus, CIS-mediated depletion of iron-containing dystrophic microglia would be beneficial at certain stages of disease progress.

The therapeutic efficacy of CIS is ascribed to well-known, nanoparticle-mediated, dose-enhancing phenomena (low-energy electron emission) from irradiated high-Z nanoparticles, such as intraplaques or impaired ferritin-released magnetite19,46,47,48,49,50. Combined Auger and interatomic Coulombic decay (ICD)-driven electron emission is available only from nanoclusters with high Z atoms19,51; potentially, CIS does not induce therapeutic effects from individual isolated iron atoms, such as the intracellular labile iron pool (LIP), due to the absence of an ICD path in LIP. Therefore, the enhanced CIS-driven cytotoxicity in Aβ-pretreated SH-SY5Y cells suggested the release of magnetite, rather than individual iron atoms, from ferritin, as shown in Fig. 8B. When the magnetite is treated by CIS treatment, it releases electrons and produces the Fenton effect, leading to cell death. Intracellular Aβ accumulation occurs at the onset of AD pathology, suggesting continuous induction of iron release from ferritin and the formation of pathological ferritin52,53. Therefore, magnetite formation and release from pathological ferritin may be the primary source of endogenous magnetite in the AD brain.

In the present study, the therapeutic effect of CIS was derived from a single treatment. Limitations of CIS would be the potential long-term effects of radiation damage with a single plateau dose of 4 Gy on neuronal microstructures such as dendritic spines. Changes in the number or the length of spines are not examined after CIS. Further longitudinal and dose-fractionation studies on normal brain tissue are necessary to address safety concerns despite the absence of overt tissue damage after a single treatment19. CIS-induced radiation-induced tissue damage depends on the LET from the plateau dose, which is much lower than the Bragg peak dose, and iron oxide nanoparticles deposited during iron deposition are exposed to the transmitted Bragg peak dose, which mostly activates electron emission without deposition. Another advantage of CIS treatment for preserving normal tissue is its spatial-selective curing effect, which may be modulated by microbeams or site-selective irradiation.

Conclusions

We investigated the role of insoluble iron deposition in microglia-driven neuroinflammation upregulation via CIS-driven depletion and downregulation of inflammatory response cascades. CIS treatment has multiple effects on disease-modifying effects on AD pathology through the depletion of both iron deposition and associated inclusion bodies. Based on these results, we found that CIS treatment promoted memory improvement through the modulation of neuroinflammation, a noninvasive, disease-modifying, and nonpharmacologic option for treating AD.

Data availability

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Telling, N. D. et al. Iron biochemistry is correlated with amyloid plaque morphology in an established mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. Chem. Biol. 24, 1205–1215 (2017).

Choi, Y. & Kim, J-K. Investigation of the redox state of magnetite upon Aβ-fibril formation or proton irradiation; implication of iron redox inactivation and β-amyloidolysis. MRS Commun. 8, 955–960 (2018).

Everett, J. et al. Iron stored in ferritin is chemically reduced in the presence of aggregating Aβ (1–42). Sci. Rep. 10, 10332 (2020).

Everett, J. et al. Evidence of Redox-Active Iron formation following aggregation of ferrihydrite and the Alzheimer’s disease peptide β-Amyloid. Inorg. Chem. 53, 2803–2809 (2014).

Balejcikova, L., Siposova, K., Kopcansky, P. & Safarik, I. Fe(II) formation after interaction of the amyloid β-peptide with iron-storage protein ferritin. J. Biol. Phys. 44, 237–243 (2018).

Quintana, C. & Gutiérrez, L. Could a dysfunction of ferritin be a determinant factor in the etiology of some neurodegenerative diseases? Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1800, 770–782 (2010).

Smith, M. A. et al. Increased iron and free radical generation in preclinical alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 19, 353–372 (2010).

Zeineh, M. M. et al. Activated iron-containing microglia in the human hippocampus identified by magnetic resonance imaging in alzheimer disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 36, 2483–2500 (2015).

Kenkhuis, B. et al. Iron loading is a prominent feature of activated microglia in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 9, 27 (2021).

Quintana, C. et al. Study of the localization of iron, ferritin, and hemosiderin in Alzheimer’s disease hippocampus by analytical microscopy at the subcellular level. J. Struct. Biol. 153, 42–54 (2006).

Zhang, N., Yu, X., Xie, J. & Xu, H. New insights into the role of ferritin in Iron homeostasis and neurodegenerative diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 58, 2812–2823 (2021).

Ryan, S. K. et al. Microglia ferroptosis is regulated by SEC24B and contributes to neurodegeneration. Nat. Neurosci. 26, 12–26 (2023).

Wang, F. et al. Iron dyshomeostasis and ferroptosis: A new Alzheimer’s disease hypothesis? Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 830569 (2022).

Ward, R. J., Dexter, D. T. & Crichton, R. R. Iron, neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 7267 (2022).

Lawrence, J. M., Schardien, K., Wigdahl, B. & Nonnemacher, M. R. Roles of neuropathology-associated reactive astrocytes: a systematic review. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 11, 42 (2023).

Ben Haim, L., Carrillo-de Sauvage, M. A., Ceyzériat, K. & Escartin, C. Elusive roles for reactive astrocytes in neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 9, 278 (2015).

Singh, N. et al. Brain iron homeostasis: from molecular mechanisms to clinical significance and therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 20, 1324–1363 (2014).

Gleason, A. & Bush, A. I. Iron and ferroptosis as therapeutic targets in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotherapeutics 18, 252–264 (2021).

Seo, S-J. et al. Proton stimulation targeting plaque magnetite reduces Amyloid-β plaque and Iron redox toxicity and improves memory in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. J. Alzheimer’s Disease. 84, 377–392 (2021).

Kim, J-K., Seo, S-J. & Jeon, J-G. Ion beam stimulation therapy with a nanoradiator as a site-specific prodrug. Front. Phys. 8, 270 (2020).

Jeon, J. K. et al. Coulomb nanoradiator-mediated, site-specific thrombolytic proton treatment with a traversing pristine Bragg peak. Sci. Rep. 6, 37848 (2016).

van Marlen, P. et al. Bringing FLASH to the clinic: treatment planning considerations for ultrahigh Dose-Rate proton beams. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 106, 621–629 (2020).

Navarro, A., Tolivia, J. & Del Valle, E. Congo red method for demonstrating amyloid in paraffin sections. J. Histotechnol. 22, 305–308 (1999).

Leger, M. et al. Object recognition test in mice. Nat. Protoc. 8, 2531–2537 (2013).

Kruger, N. J. The Bradford method for protein quantitation. Methods Mol. Biol. 32, 9–15 (1994).

Mahmood, T. & Yang, P. C. Western blot: technique, theory, and trouble shooting. N Am. J. Med. Sci. 4, 429–434 (2012).

McIntosh, A. et al. Iron accumulation in microglia triggers a cascade of events that leads to altered metabolism and compromised function in APP/PS1 mice. Brain Pathol. 29(5), 606–621 (2019).

Nnah, I. C. & Wessling-Resnick, M. Brain iron homeostasis: a focus on microglial iron. Pharmaceuticals. 11, 129. (2018).

Xie, Y., Kang, R., Klionsky, D. J. & Tang, D. GPX4 in cell death, autophagy, and disease. Autophagy 19, 2621–2638 (2023).

Chun, H. & Justin Lee, C. Reactive astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease: A double-edged sword. Neurosci. Res. 126, 44–52 (2018).

Strbak, O. et al. Quantification of Iron release from native ferritin and Magnetoferritin induced by vitamins B2 and C. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 6332 (2020).

Gao, C., Jiang, J., Tan, Y. & Chen, S. Microglia in neurodegenerative diseases: mechanism and potential therapeutic targets. Sig Transduct. Target. Ther. 8, 359 (2023).

Park, J. S. et al. Blocking microglial activation of reactive astrocytes is neuroprotective in models of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 9, 78 (2021).

Chun, H. et al. Severe reactive astrocytes precipitate pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease via H2O2 – production. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 1555–1566 (2020).

Behl, T. et al. Role of monoamine oxidase activity in Alzheimer’s disease: an insight into the therapeutic potential of inhibitors. Molecules 26, 3724 (2021).

Salta, E. et al. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease: A roadmap to clinical relevance. Cell. Stem Cell. 30, 120–136 (2023).

Moreno-Jiménez, E. P. et al. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis is abundant in neurologically healthy subjects and drops sharply in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med. 25, 554–560 (2019).

Scopa, C. et al. Impaired adult neurogenesis is an early event in Alzheimer’s disease neurodegeneration, mediated by intracellular Aβ oligomers. Cell. Death Differ. 27, 934–948 (2020).

Lazarov, O. & Marr, R. A. Neurogenesis and Alzheimer’s disease: at the crossroads. Exp. Neurol. 223, 27–281 (2010).

Colonna, M. & Butovsky, O. Microglia function in the central nervous system during health and neurodegeration. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 35, 441–468 (2017).

Rodríguez-Callejas, J. D. et al. Loss of ferritin-positive microglia relates to increased iron, RNA oxidation, and dystrophic microglia in the brains of aged male marmosets. Am. J. Primatol. e22956 (2019).

McCarthy, R. C. et al. Inflammation-induced iron transport and metabolism by brain microlgia. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 7853–7863 (2018).

Grundke-Iqbal, I. et al. Ferritin is a component of the neuritic (senile) plaque in alzheimer dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 81, 105–110 (1990).

Connor, J. R., Snyder, B. S., Beard, J. L., Fine, R. E. & Mufson, E. J. Regional distribution of iron and iron-regulatory proteins in the brain in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 31, 327–335 (1992).

Yoshida, T., Tanaka, M., Sotomatsu, A. & Hirai, S. Acivated microglia cause superoxide-mediated release of iron from ferritin. Neurosci. Letter. 190, 21–24 (1995).

Kim, J. K. et al. Enhanced proton treatment in mouse tumors through proton irradiated nanoradiator effects on metallic nanoparticles. Phys. Med. Biol. 57, 8309–8323 (2012).

Porcel, E. et al. Gadolinium-based nanoparticles to improve the hadrontherapy performances. Nanomedicine 10, 1601–1608 (2014).

Kim, H. K. et al. Enhanced production of low energy electrons by alpha particle impact. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108, 11821–11824 (2011).

Seo, S. J., Jeon, J. K., Han, S. M. & Kim, J. K. Reactive oxygen species-based measurement of the dependence of the coulomb nanoradiator effect on proton energy and atomic Z value. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 93, 1239–1247 (2017).

Peukert, D., Kempson, I., Douglass, M. & Bezak, E. Metallic nanoparticle radiosensitization of ion radiotherapy: A review. Phys. Med. 47, 121–128 (2018).

Kim, J. K. et al. Enhanced generation of reactive oxygen species by the nanoradiator effect from Core-Inner shell Photo-Excitation or proton impact on nanoparticle atomic clusters. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 54, 423–431 (2015).

Bayer, T. A. & Wirths, O. Intracellular accumulation of amyloid-Beta - a predictor for synaptic dysfunction and neuron loss in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2, 8 (2010).

Gouras, G. K., Tampellini, D., Takahashi, R. H. & Capetillo-Zarate, E. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid accumulation and synapse pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 119, 523–541 (2010).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the Rare Isotope Science Project of the Institute for Basic Science, which is funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT and NRF of Korea (2013M7A1A1075764) and partially supported by NRF-2022R1F1A1073750.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.K. designed the overall study and experiments and wrote the manuscript. E.K. designed and analyzed the western blot analysis and wrote the manuscript. A.Z. and T.I. carried out animal care, mouse breeding procedures, and genetic examination. T.K. performed the irradiation experiment with animal care and sectioned the mouse tissue samples. T.H. calculated dosimetry for CIS. W.L. performed the CIS experiments and western blot and histological assays. Y.C. performed the in vitro experiments and the statistical analysis, and obtained histological sections. O.K. analyzed the results of the behavioral task. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal protocols received approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Tsukuba (protocols #210097 and #21–193).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, WS., Kokubo, T., Choi, Y. et al. Carbon ion stimulation therapy reverses iron deposits and microglia driven neuroinflammation and induces cognitive improvement in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Sci Rep 15, 7938 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91689-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91689-3