Abstract

A novel global cooperative phenomenon was observed in monolayers of HeLa cervical cancer cells that exhibited glycolytic oscillations but did not exhibit synchronisation or partial synchronisation. The analysis of causality of the oscillations between cell pairs in the cell-monolayer sheet revealed a hidden causal interaction network. Furthermore, the network exhibits characteristics of a broad-scale network. This suggests that key cells perform a hub-like function in the network and that the population of HeLa cells forms metabolically connected functional network rather than randomly connected one. Unlike previous work that focused on the synchronisation of glycolytic oscillations in the HeLa cells, the present study analysed the causality between the oscillating cells by Convergent Cross Mapping (CCM), which is based on the phase-space reconstruction of time-series data and is used to find causality in weakly coupled components of nonlinear dynamical systems. We believe that the framework proposed in this study is useful for investigating the hidden state of a group of cells and can accelerate studies on cellular metabolic phenomena including metabolic oscillations in \(\:\beta\:\) cells within islets of Langerhans. It would also be applicable to systems of weakly coupled oscillators that may include hidden cooperative phenomena.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cell-cell interactions play important roles in various biological processes, including cell development, tissue homeostasis, and immune interactions in diseases1. They are particularly essential not only for multicellular organisms but also for unicellular organisms, such as yeasts, to adapt to the environment or acquire multicellularity2.

Cell-cell interactions also play important roles in cellular metabolism. Metabolic symbiosis is a good example in which cells exchange metabolites such as lactate to obtain energy efficiently or adapt to tissue microenvironments3,4. Metabolic symbiosis has been reported in brain, tumours, and muscle tissues5,6,7.

Under certain conditions, dynamic cell-cell interactions can result in synchronisation or partial synchronisation8,9 to cells exhibiting self-oscillations in the concentrations of metabolites, which are known as metabolic oscillations10,11, or glycolytic oscillations in the case of oscillations occurring in the glycolytic pathway12,13. Metabolic synchronisation can be observed under conditions in which cellular interactions are strong8,9,11,14. In yeast cells, acetaldehyde is an intercellular coupling mediator that functions as a paracrine signal8,12 .

In this study we report a novel global cooperative phenomenon in monolayers of HeLa cervical cancer cells that exhibited glycolytic oscillations but did not exhibit either synchronisation or partial synchronisation. The global cooperative phenomenon observed in this study was a causal interaction network of the cells, as revealed by the analysis of the causality between the cell pairs in the monolayer sheet of cells. Furthermore, the causal metabolic interaction network exhibited the characteristics of a broad-scale network15, which is a class of small-world and complex network15,16,17 and exhibits power law scaling in its degree distribution over limited range of degree. This suggests that key cells perform a hub-like function in the network. Notably, “\(\:\beta\:-\)cell hubs” have been found in the populations of pancreatic \(\:\beta\:\) cells exhibiting glucose-stimulated synchronous calcium oscillations, suggesting that \(\:\beta\:\) cells form a scale-free-like network in metabolism18,19,20. In our previous studies, cooperative phenomena such as synchronisation or partial synchronisation have not been observed in HeLa cervical cancer cells21,22, probably due to their weak interactions8,9.

The causality between the oscillating cells was analysed using Convergent Cross Mapping (CCM)23, which is based on the phase–space reconstruction of time-series data24 and is used to find causality in weakly coupled components of nonlinear dynamical systems25. Consequently, a hidden global interaction network of the cells was observed in this study, which was assumed to be a preliminary state for synchronisation. We believe that this method is useful for investigating the hidden state of a group of cells and can accelerate studies on the metabolic phenomena in cells. In addition, it would also be applicable to phenomena that could have hidden global interactions and cooperative phenomena in systems of weakly coupled oscillators.

Optical micrograph of HeLa cells in monolayers and glycolytic oscillations in individual cells. (A) Each cell was surrounded by yellow line and numbered. The colors of cells indicate frequencies of oscillations in the cells. The number of oscillatory cells was \(\:N=254\). Non-oscillatory cells are black or grey in color. The scale bar is 100 \(\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\). The number of oscillating cells was 254 among the 325 cells, and the fraction of oscillating cells was 0.78 (= 254/325). (B) Time course of fluorescence of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) from individual cells. The trended and noise were reducted. The data until 130 s were removed because large baseline shifts in NADH fluorescence were lasted until 130 s upon addition of 25 mM glucose to the cells at 30 s. The numbers at the right-hand side of the data indicate individual cells assigned arbitrary in the optical micrograph in panel (A).

Results

Glycolytic oscillations in HeLa cells

Optical micrographs of the monolayers of HeLa cells exhibiting glycolytic oscillations are shown in Fig. 1A and Movie 1; the colours of individual cells in Fig. 1A indicate the frequency of oscillations in the fluorescence of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) from individual cells. In Movie 1, the high and low values of NADH in the oscillating cells are coloured red and blue, respectively, and the sizes of the coloured circles indicate the relative amplitudes of the oscillations.

The time series of glycolytic oscillations in individual HeLa cells are shown in Figure 1B. The oscillatory behaviours were statistically analysed (Supplementary Fig. 1), and the distributions of frequency, duration of oscillations, and number of oscillations in the populations of HeLa cells were obtained as follows: the range of frequencies was 0.0075 to 0.1000 Hz with a mean of 0.0603 Hz, the median duration of oscillations was 208.5 s, and the median number of oscillations was 13.

Oscillatory dynamics in HeLa cells on a local scale

To get insights into the possible presence of synchronous dynamics on a local scale, we analysed the oscillatory behaviours between cell pairs as a function of intercellular distance. First, we selected cells located on a line as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2A and compared their oscillatory wave forms by intercellular distance (Supplementary Fig. 2B). We did not observe any trends or synchronous dynamics in the oscillations as a function of the intercellular distance. Second, we investigated the frequency differences between all cell pairs; their distribution and average values as a function of the intercellular distance are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3A and 3B, respectively. We observed no increasing trends of the frequency difference in both the distribution and the average values with increasing the intercellular distance.

Third, we investigated temporal oscillations in nine cells surrounding a cell 290, which exhibited oscillations with large amplitudes, and found no synchronous dynamics locally as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. Certainly, we can see synchronous-like oscillations, for instance, between cells 146 and 130 (Supplementary Fig. 4B), however, they happened within short period of time, we cannot conclude they were synchronisation.

Thus, we conclude that no synchronous dynamics were exhibited in the HeLa oscillations on a local scale qualitatively (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 4) and quantitatively (Supplementary Fig. 3) as well.

Asynchronous collective oscillations in HeLa cells

To investigate synchronisation including partial synchronisation of oscillations in the populations of HeLa cells quantitatively, we calculated the instantaneous intensities, phases, frequencies (\(\:{f}_{i}\)), and phase difference (\(\:\varDelta\:\varphi\:\)) between the phase of each individual cell (\(\:{\varphi\:}_{i}\)) and that of the average phase of all cells (\(\:\stackrel{-}{\varphi\:}\)), as well as the time-dependent order parameter26 K(t) as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. We did not observe synchronous patterns in the intensities and phases (Supplementary Fig. 5A and 5B, respectively).

Though the K(t) values were between 0.2 and 0.3 (Supplementary Fig. 5E), we address that neither coordinated dynamics in a local scale nor partial synchronisation were exhibited in the HeLa oscillations. Three possible explanations for the above consideration are as follows: (i) The low K(t) values do not necessarily indicate the presence of coordinated dynamics in a local scale; low K(t) values between 0.1 and 0.2 are reported to indicate a complete desynchronization among yeast cell populations at low cell densities (0.01 and 0.04%) immobilised on a coverslip8, as well as K(t) values between 0.3 and 0.4 are also reported a loss of spatiotemporal synchronisation and break down of community structure among yeast cells loaded densely in a microfluidic chamber and exposed to very high concentrations (20 and 24 mM) of cyanide27; (ii) The continuous periodic fluctuation in K(t) values at the low level (Supplementary Fig. 5E) reflects the fact that the frequency distributions were large (Supplementary Fig. 1A and 5 C) and thus no phase synchronisation was achieved during the oscillations. Actually, the half-width of frequency distribution was much larger (28 mHz) in our experiment (Supplementary Fig. 1A) than that (approximately 3\(\:-\)5 mHz) in the partial synchronisation in yeast cells9; (iii) The characteristic feature of the frequency and phase in partial synchronisation was not observed in our experiments. Namely, the first narrowing of the frequency distribution and successive convergence of the distribution of the phase difference (\(\:\varDelta\:\varphi\:\)) were not observed in our HeLa cells (Supplementary Fig. 5 C and 5D), contrarily, they were clearly observed in partial synchronisation in yeast cells9.

In summary, we conclude that neither synchronisation nor partial synchronisation were exhibited in the populations of HeLa cells. This is probably due to very weak cell-cell interactions among the HeLa cells21,22. Thus, we address that such a weak and hidden interaction among the group of HeLa cells exhibiting metabolic oscillations warrants further exploration. Accordingly, we analysed the causality between the oscillating cells by the Convergent Cross Mapping (CCM) method23, which has been used to find causality in weakly coupled components of nonlinear dynamical systems.

Causality of glycolytic oscillations in HeLa cells

To investigate the weak cell-cell interactions in glycolytic oscillations in HeLa cells, we focused on the causality of the oscillations. The time series of all pairs of cells exhibiting oscillations were analysed for the first 200 s (131\(\:-\)330 s) with a time window of 100 s, which was moved in increments of 5 s (Fig. 2A). For example, we used time-series data from 131 to 230 s to perform the first set of CCM analyses. Subsequently, the time series data from 136 to 235 s were used to perform the second set of CCM analyses and so on. The final set of analyses was performed from 231 to 330 s. A total of 21 sets of data were obtained. Thus, we observed the time-wise development of the causality of interactions between the cells.

In Fig. 2B, we present the number (\(\:{N}_{\text{C}\text{C}\text{M}\:0.8}\)) of cell pairs whose CCM values were larger than 0.8 as a function of their intercellular distance \(\:d\). The value 0.8 was determined by a surrogate test confirming the reliability of the CCM analysis (see Methods: Convergent Cross Mapping (CCM) analysis). A time series of 131\(\:-\)230 s was used for the analysis for a methodological choice (see Methods: Convergent Cross Mapping (CCM) analysis). The plots exhibited a convex shape and the maximum of \(\:{N}_{\text{C}\text{C}\text{M}\:0.8}\) was located around the intercellular distance of \(\:250-300\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\). Due to the spatial distribution of cells in the investigated field of microscopy (Fig. 1A), the number (\(\:{N}_{\text{p}\text{a}\text{i}\text{r}\text{s}}\)) of cell pairs depended on \(\:d\) (Fig. 2C) and exhibited a convex shape, similar to that of \(\:{N}_{\text{C}\text{C}\text{M}\:0.8}\). To determine the frequency of appearance of cells whose CCM was more than 0.8, we normalised the \(\:{N}_{\text{C}\text{C}\text{M}\:0.8}\) with \(\:{N}_{\text{p}\text{a}\text{i}\text{r}\text{s}}\). The ratio \(\:{r}_{\text{C}\text{C}\text{M}\:0.8}\) (\(\:={N}_{\text{C}\text{C}\text{M}\:0.8}/{N}_{\text{p}\text{a}\text{i}\text{r}\text{s}}\)) was plotted as a function of \(\:d\) (Fig. 2D). A higher frequency of cell pairs exhibiting high causal interactions was observed for short intercellular distances, and the causal interactions seemed to decrease rapidly with increasing \(\:d\). In addition, the results of the CCM analysis for the three time zones are shown in Fig. 2D; differently coloured dots indicate data from different time series: blue, 131\(\:-\)230 s; orange, 161\(\:-\)260 s; grey, 221\(\:-\)320 s. A similar dependency on \(\:d\) was observed for those results.

Causality of oscillations between all pairs of two cells in the monolayers analyzed by Convergent Cross Mapping (CCM). (A) Causality of oscillations between all pairs of two cells at their intercellular distance \(\:d\) from 10 \(\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) to 500 \(\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) was analyzed. (B) distribution of CCM values larger than 0.8, \(\:{N}_{\text{C}\text{C}\text{M}\:0.8}\), within the intercellular distance between \(\:d\) and \(\:d+5\) \(\:\mu\:m\). (C) Distribution of number of cell-pairs, \(\:{N}_{\text{p}\text{a}\text{i}\text{r}\text{s}}\). (D) ratio, \(\:{r}_{\text{C}\text{C}\text{M}\:0.8}\), (\(\:={N}_{\text{C}\text{C}\text{M}\:0.8}/{N}_{\text{p}\text{a}\text{i}\text{r}\text{s}}\)) of the number of CCM values to the number of cell-pairs as a function of \(\:d\). The number of analyzed pair of cells was 254C2 = 32,131.

To investigate the dependence of causal interactions on the intercellular distance in more detail, the plot shown in Fig. 2D was replotted on a double logarithmic scale, as shown in Fig. 3. A straight line-like relationship was observed in a range of intercellular distances of approximately \(\:10-70\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) (Fig. 3B). This indicates that the data followed a power law. The slope of the straight line was 1.4, and the dependence of the normalised causal interactions \(\:{r}_{\text{C}\text{C}\text{M}\:0.8}\) on the intercellular distance \(\:d\) was fitted using Eq. (1):

Double logarithm plot of the causality (\(\:{r}_{\text{C}\text{C}\text{M}\:0.8}\)) of oscillations as a function of intercellular distance. (A) The causality (\(\:{r}_{\text{C}\text{C}\text{M}\:0.8}\)) as a function of the inter cellular distance from 10 \(\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) to 500 \(\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\). Plots are calculated values for the time series for 100 s starting from 131 s (blue), 161 s (orange), and 211 s (grey). Green line is the fitted curve of Eq. (1). Blue straight line is a fit by a power law to the plots with short intercellular distances from 10 to 70 \(\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\). (B) Enlargement of the plots for the short intercellular distance from 10 to 70 \(\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\). Straight line is a fit to the plots by a power law.

The fitted curve is shown in green in Fig. 3A. Notably, the constant value 0.01 demonstrates the noise level that is independent of \(\:d\) and covers the possible power law dependence on \(\:d\) even for \(\:d>70\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\). The horizontal line coming from random noise and the straight slope line coming from the power law mode are crossed at the distance between 100 \(\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\) 200 \(\:{\upmu\:}\)m. This suggests that the analysis of areas with distance less than 200 \(\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) (4\(\:-\)6 cells apart) is meaningful, but that of areas with distance more than 200 \(\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) are not so meaningful, as they are buried in noise.

Complex network of the causality of the oscillations

To visualise the spatial structure of the causal interaction of the glycolytic oscillations in HeLa cells, causal links with CCM values more than 0.8 were drawn between two cells for three different ranges of intercellular distance (Fig. 4A\(\:-\)4 C). Qualitatively, different network structures were obtained, depending on the intercellular distance. To further investigate the network structure, we assigned the cells as nodes and the number of their causal links as degree or node degree, and then analysed the relationships by applying network theory17.

We present the distribution of node degree on a double logarithmic scale in Fig. 4D\(\:-\)4F. The plots were fitted by a straight line with a slope of \(\:-\)1.7 for the nodes (cells) located at the distance of \(\:0-100\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) (Fig. 4D), indicating that the causal network followed power distribution. In contrast, the causal networks for the nodes located at the distance of \(\:100-200\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) seemed to be fitted by a straight line; however, a Poisson component is mixed (Fig. 4E). The nodes located at a distance greater than \(\:200\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) can be fitted by a Poisson distribution (Fig. 4F) arising from the stochasticity of connection, namely, noise components (Fig. 3), though a weak contribution of a power component can be observed at the large degree around 10. This picture perfectly fits with the results shown in Fig. 3 in that the information of the causal interaction is strong enough to analyse when the distance between the cells is equal or less than 200 \(\:{\upmu\:}\)m; conversely, the information is weak and negligible when the distance is greater than 200 \(\:{\upmu\:}\)m (4\(\:-\)6 cells apart).

Therefore, we decided to focus on the interactions of the cells whose distance is equal or less than 200 μm. It is noteworthy that the component of the power distribution described above suggests that the entire network of causal interactions of this cell group forms a broad-scale or truncated scale-free networks15 within 200 μm. These networks belong to classes of small-world networks including scale-free networks16,17 and their power-law scaling is limited to some range of degree followed by a sharp cutoff, like an exponential or Gaussian decay of the tail15. Our results showed the maximum degrees around 10, and the distribution did not strictly follow a power law (Fig. 4D and E). Since the network size was small in the HeLa system, we could not confirm the power-law over several orders of magnitude. In addition, purely scale-free networks are reported to be rare28. For these reasons, we refer to the causal network of HeLa oscillations as broad-scale network in the present study.

Causal links of glycolytic oscillations in HeLa cells in monolayers and complex network analysis. (A),(B): Oscillatory cells in the time series of \(\:131-230\:\text{s}\) with high causality (CCM \(\:>\) 0.8) were connected each other in the intercellular distance of (A) \(\:0-100\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\), (B) \(\:100-200\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\), and (C) 2\(\:00-300\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\). The arrows indicate the causal direction from a cell (arrow bottom) to the other cell (arrow tip). The colors of circles on the cells indicate the direction of causality: red, cause; blue, effect; green, cause and effect. The number of analyzed cells was \(\:N=254\). (D),(F): Double logarithmic plots of the frequency of appearance of degree (causal links) as a function of the number of degrees. The analyzed ranges of intercellular distance between the two cells were as follows: (D) \(\:0-100\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\), (E) \(\:100-200\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\), and (F) \(\:200-300\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\), \(\:300-400\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\), and \(\:400-500\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\). In all panels, the analyzed data (circles connected with lines) were the average of 21 time series of the time window of 100 s from 131 to 330 s with increments of 5 s. Doted lines in blue are power distribution with a power number \(\:-\)1.7, and dotted lines in orange are Poisson distribution with mean 2.8.

To confirm the broad-scale characteristics in the network of HeLa cells, we constructed a network structure by connecting all the oscillating cells, with a probability of 0.1 for convenience, located within 200 \(\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) (Supplementary Fig. 6). The network exhibited a Poisson distribution in the double logarithmic plot. This indicates that the causal networks, as shown in Fig. 4A and B, are the result of power distribution of the nodes (oscillating cells) within 200 \(\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) (Fig. 4D and E) and not merely stochastic interactions of the oscillating cells. Thus, it can be said that causal interactions of glycolytic oscillations in HeLa cells occurred locally and that the typical distance for this interaction was within 200 \(\:{\upmu\:}\)m (4\(\:-\)6 cells apart).

Spatiotemporal changes in the network structure

To further analyse the network structure, the characteristics of the subgraphs in the network were investigated. Subgraphs are groups of interconnected nodes, and the number of interconnected nodes is known from their sizes. An example of the sets of subgraphs in the causal network within the distance of \(\:200\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) produced from the time series data of 131\(\:-\)230 s is shown in Supplementary Fig. 7; the number of the subgraphs were 8 (Supplementary Fig. 7A), and the size of the largest subgraph was 141, the shortest path was 5.35, and the average clustering was 0.398 (Supplementary Fig. 7B).

The relationship between the number and degree of nodes is shown in Fig. 5 in the bar chart (Fig. 5A) and double logarithmic plots (Fig. 5B). The distribution of the degree can be fitted with a combination (blue curve) of a power distribution (green line) and a Poisson distribution (orange curve), as shown in Fig. 5B. This distribution cannot be explained using a simple Poisson distribution, particularly at large node degrees. Thus, it may well be said that a broad-scale network was also organised in the largest subgraph even if it contains random connections.

The number of subgraphs and their sizes varied with elapsed time, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 8, and the details of the change in the number of subgraphs and their sizes as a function of the time are listed in Supplementary Table 1. A very large subgraph consisting of 141 cells and other small subgraphs consisting of fewer than 19 cells appeared at the beginning of the analysis (at 131 s), and the large subgraph decomposed into smaller subgraphs over time. Interestingly, the decrease in the size of the largest subgraph was discontinuous, and the size suddenly collapsed to a small one at 200 s (Supplementary Fig. 9). This behaviour is similar to that of percolation29. Notably, most of the cells still oscillated at time of 200 (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. 1B), and therefore this percolation was not caused by the cessation of oscillations.

The relationship between number of nodes (cells) and degree of nodes in the largest subgraph as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. (A) Distribution of number of nodes as a function of degree of node. (B) Double logarithmic plot of the frequency of number of nodes as a function of degree of node. In (B), plots with blue in color are data from the experiments, green straight line is a power function with a power number \(\:-\)1.1, and orange curve is a Poisson function with mean 5.0.

Oscillatory signal transduction by diffusion

To further investigate the origin of the power-law dependence of causality (\(\:{r}_{\text{C}\text{C}\text{M}\:0.8}\)) on intercellular distance (Fig. 3), we considered oscillatory signal transduction by diffusion. The dimensionless form of the diffusion equation can be written as:

where \(\:c\:\)is the concentration of a substrate, \(\:\tau\:\) is time, \(\:x\) and \(\:y\) are spaces, and \(\:\delta\:\) is diffusion coefficient. Amplitude (max-min) of the pulsate concentration wave of a substrate (lactate), which is periodically generated from a source (cell) and diffused in the medium, decays with distance. The following relationships between the dimensionless and real variables are used in the calculation:

Simulation of periodic change in the concentration of a substrate at a certain point. A periodic change in the concentration of a substrate, which was generated from a cell and diffused in the media, at different dimensionless points \(\:d\)=5 (blue line), \(\:d\)=10 (orange line), \(\:d\)=20 (green line), and \(\:d\)=30 (red line) from the cell. The frequency of \(\:0.0571\text{H}\text{z}\) was used for the calculation with reference to the experiment (Supplementary Fi.g. 1 A). The above dimensionless distance (\(\:d\)) corresponds to approximately \(\:10\:d\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) in the real system. See Eq. (3).

where \(\:t\) is the time in \(\:\left[\text{s}\right]\), \(\:X\) and \(\:Y\) are spaces [\(\:\text{m}]\), and \(\:D\) is the diffusion coefficient in real systems [\(\:{\text{m}}^{2}{\text{s}}^{-1}\)], respectively. The constants \(\:a\:\left[\text{s}\right]\) and \(\:b\:\left[\text{m}\right]\) convert the dimensionless variables into variables in real systems. Numerical calculations were performed to investigate the behaviour of this equation under certain conditions. The differential equation was discretised with a forward difference for the time part and a centred difference for the space part. “Python (3.8.10)” was used for calculations30.

The periodic change in the amplitude at a point (cell) located at a certain distance from the source is shown in Fig. 6. Here, the diffusion coefficient \(\:D=0.5\times\:{10}^{-9}\:{\text{m}}^{2}{\text{s}}^{-1}\) for lactate31 and the oscillatory frequency of \(\:0.0571\:\text{H}\text{z}\) in the experiments (Supplementary Fig. 1A) was used for calculations. The change in the lactate-concentration was very large at a dimensionless distance \(\:d=5\), which was approximately 50 \(\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) from the source cell in the real system and then becomes unambiguous with increasing distance. No change in the concentration (zero-amplitude) was observed at a distance \(\:d=30\) (approximately 300 \(\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\)). Notably, little causality was observed at 300 \(\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) in the causal analysis, as shown in Fig. 3.

Change in the amplitude (max.\(\:-\)min.) of concentration as a function of distance from a cell generating a substrate for cell-cell communication. (A) Linear-log plot. (B) Double logarithmic plot. The curves with green in color are fit to the calculated values (blue points) with power function, and the curves with orange in color are fit to the values with exponential function.

Dependence of amplitude \(\:A\) (max-min) of the pulsate concentration wave as a function of the intercellular distance (\(\:d\)) from the source is shown in Fig. 7. The amplitude decreased with \(\:d\) to the power of \(\:-\)2.3 (\(\:A=8\times\:{d}^{-2.3}\)) within the intercellular distance of approximately 200 \(\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\), whereas \(\:A\) decreased exponentially with \(\:d\) (\(\:A=0.11\:{e}^{-0.14\:d}\)) beyond the intercellular distance of 200 \(\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\). Notably, the amplitude of concentration at the distance of 200 \(\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) was approximately \(\:{10}^{-2}\) to that of the initial value, indicating that the oscillatory signals were too small to establish cell-cell communication beyond this distance. Although, the values for the power dependence on \(\:d\) were different, \(\:-\)1.4 for the causality (Fig. 3) and \(\:-\)2.3 for the diffusion model (Fig. 7), it may well be said that the power dependence of the causality of the glycolytic oscillations on the cellular distance was due to the oscillatory signal generated from the cells that diffused in the media and mediated the cell-cell communication.

Discussion

We have shown a hidden causal interaction between HeLa cells exhibiting glycolytic oscillations in a system of cell monolayers. A complex network (broad-scale network) emerged from the causal interaction of glycolytic oscillations in the populations of HeLa cells (Fig. 1\(\:-\)4). The distribution of degree (the number of causal connections) of nodes (cells) in the network exhibited a power law (Fig. 4) within the cellular distance of approximately 200 \(\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) (4\(\:-\)6 cells apart), exhibiting the feature of broad-scale networks. We further investigated the characteristics of subgraphs in the network and found that the largest subgraph also exhibited a broad-scale feature in its distribution of nodes (Fig. 5) and decomposed into smaller subgraphs in time (Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Table 1). The decomposition was accompanied by discontinuous collapse at a critical size, which is a feature of percolation (Supplementary Fig. 9). Finally, we explained the possible mechanism of power-law dependence of causality (\(\:{r}_{\text{C}\text{C}\text{M}\:0.8}\)) on the intercellular distance (Fig. 3) by oscillatory signal transduction by diffusion (Figs. 6 and 7). This signal transduction model explained the dependence of the causality on the distance quantitatively.

We did not observe synchronous behaviours in the HeLa oscillations. This was confirmed by the qualitative comparison of oscillations in nearby cells (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 4) as well as the qualitative analysis of collective oscillations (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 5). Previous studies also observed no synchronous oscillations in HeLa cells in cell monolayers21 and in three-dimensional cell aggregates called spheroids22. The spheroidal cell system was expected to enhance the cell-cell interaction of HeLa cells that adhere each other via adhesion molecules, cadherins32, and would induce synchronisation of oscillations between HeLa cells. However, contrary to the expectations, even adjacent cells in the spheroids oscillated independently within 10% difference in frequency and exhibited no synchronisation22. So far, we have not observed synchronous behaviour of glycolytic oscillations in another type of cancer cells, DU145 prostate cancer cells33.

In the case of glycolytic oscillations in yeast cells, synchronisation8,27,34,35, partial synchronisation9, and synchronised waves27,36 have been observed by using fixed cells. Thus, synchronisation was achieved by using the system of a high cell density (0.7%) on coverslips8, periodically removing cyanide exposed to the cells on microfluidic chambers35, controlling the concentrations (12\(\:\--\)16 mM) of cyanide diffusively exposed to the cells on diffusion-limited microfluidic chambers27, and increasing the cell density (\(\:1.0\times\:{10}^{9}\:\text{c}\text{e}\text{l}\text{l}\text{s}/\text{m}\text{L}\)) in the microparticles34. Increase in the cell density helps to enhance the cell-cell interactions mediated by acetaldehyde12, which is produced and released by yeast cells, and then taken up by other cells. External addition of cyanide, which binds to acetaldehyde, controls the acetaldehyde concentrations within appropriate ranges for effective cell-cell communication27. Thus, controlling the cell density or cyanide concentrations can also give rise to partial synchronisation, in which the population of cells exhibits neither complete synchronisation in frequency and phase nor complete asynchronisation9, as well as synchronised wave behaviour27,36.

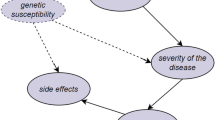

A speculative scenario of spatiotemporal synchronization with change in the cell-cell interaction. Populations of cells (coloured dots) exhibiting metabolic oscillations may undergo (A) causal complex network, (B) partial synchronization, and (C) global synchronization with increasing the cell-cell interaction. The lines connecting the dots indicate cell-cell interaction, and the colours of dots represent the characteristic of cells, such as the direction of causality: red, cause; blue, effect; green, cause and effect in panel (A), and oscillation phases in panels (B) and (C).

In Fig. 8 we present a speculative scenario of the spatiotemporal collective behaviour of cells exhibiting metabolic oscillations with changes in the strength of cell-cell interactions. The colours of cells symbolically represent the characteristic of cells, such as the oscillation phases. When the cell-cell interaction is weak, the causal relationship of glycolytic oscillations may emerge as a complex network in the cell populations (Fig. 8A), which was observed in the present study. Under these conditions, the cells connected by the weak causal interaction exhibit neither partial synchronisation nor synchronisation. In the complex networks (broad-scale networks), there exists a “metabolic hub” in the populations of cells. With increasing the cell-cell interactions, spatial clusters of partial synchronisation arise when the strength of the cell-cell interaction is medium (Fig. 8B). This type of synchronisation has been observed in yeast glycolytic oscillations9. The mechanism underlying the appearance of partially synchronised clusters is yet to be elucidated, and we speculate that the metabolic hub-cells could be the organising centre for the partial synchronisation clusters. When the cell-cell interaction further increases, global synchronisation is achieved (Fig. 8C), as reported for yeast glycolytic oscillations8. At this stage, the population of cells is completely synchronised to a unique frequency and phase. To date, neither partial nor global synchronisation has been observed in cancer cells. We will be able to observe the above scenario from a causal relationship to partial and global synchronisation in the populations of cancer cells if a longer duration of oscillations is achieved in the experiments, for instance, by using a diffusion-limited flow-chamber system27.

In the case of pancreatic \(\:\beta\:\) cells, glucose-stimulated oscillations in metabolites, calcium ions, and membrane electrical activity have been observed11. Synchronisation of the metabolic oscillations in \(\:\beta\:\) cells is reported to mediate oscillatory insulin secretion, which apparently maintains normoglycemia at lower insulin concentrations than constant secretion37. Studies of the synchronous behaviour of calcium dynamics including oscillations in \(\:\beta\:\) cell populations have revealed that \(\:\beta\:\) cells form a class of scale-free network, in which there exists a highly synchronised nodes (cells) called “\(\:\beta\:\)-cell hubs” that support the efficient propagation of glucose-stimulated calcium waves to distant islet regions18,19,20. These functional networks in \(\:\beta\:\) cells are similar to the one obtained in the present study of HeLa cells, though the methods of network evaluation are different between the \(\:\beta\:\) cell studies and the present HeLa study; the former studies calculated the correlation of calcium wave forms whereas the latter study calculated the causality of oscillations in metabolic (NADH) signals. Notably, the present study assumes that the metabolic activities in HeLa cells were the factor of causal interaction and formed the broad-scale network; this assumption is similar to a conclusion that connectivity of \(\:\beta\:\) cells within islet is due to metabolic rather than gap junctional coupling efficiency20. A theoretical study also suggests that the functional network in \(\:\beta\:\) cells is expected to be strongly influenced by metabolic dynamics rather than structural coupling by gap junctions38. Further, the CCM analysis used in the present study is more useful than the correlation analysis in \(\:\beta\:\) cell studies, because the CCM analysis can evaluate a hidden causality between two signals that may differ in waveform including frequencies and phases and therefore exhibit little correlation.

Classes of scale-free networks have generally been revealed that although the network’s connectivity is robust to random errors, it is extremely vulnerable to attacks to a hub in the network39. These characteristics of a broad-free network can be applied to the causal metabolic interaction in cancer. The causal interaction of glycolytic oscillations in the HeLa cells was probably due to the exchange of a lactate if we considered metabolic symbiosis in cancer cells mediated by lactate3. Thus, a complex lactate-mediated symbiosis network may emerge in the cancer microenvironment in the human body. In addition, metabolic symbiosis is known to enhance cancer malignancy by providing opportunities for cancer cells to obtain their energy efficiently from other cells or adapt to tissue microenvironments4,6. Therefore, knowledge of this “cancer-cell hubs” may pave the way for novel cancer therapies, which can break the possible networks of energy symbiosis in cancer.

Methods

Cultures and glucose starvation of HeLa cells

HeLa cervical cancer cells were obtained from the RIKEN BRC CELL BANK (RCB007). HeLa cells were routinely cultured in low-glucose (5 mg/L) Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, FUJIFILM Wako Chemical Co., Japan) and foetal bovine serum (FBS, 10% v/v; Hyclone, Cytiva, Tokyo, Japan) in a 5% CO2 Incubator (CO2 Incubator 9000EX, Waken Btech) at 37 °C as described elsewhere21,22.

Monolayers of each cell type were detached and seeded in the wells of a slide and chamber (Fukae-Kasei Co. Ltd., Watson Bio Lab, Japan) at a density of \(\:1\times\:{10}^{5}\) cells in 1 mL of culture medium. The seeded cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 3 d and then starved of glucose at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 24 h. The medium was then washed and changed with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS, Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC., Japan) at pH 6.9. The slide and chamber containing the cells in DPBS was set on the stage of an inverted fluorescence microscope (BZ-X800, KEYENCE, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a thermo-plate (TPi-CKX, Tokai Hit, Fujinomiya, Japan) at 37 °C.

Fluorescence microscopy and image acquisition

Glycolytic oscillations were achieved by adding 25 mM glucose to glucose-starved HeLa cells and observing the fluorescence of intracellular nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), which was excited with light at 365 nm; its emission was measured at 435–485 nm with a filter set (BZ-X filter DAPI, KEYENCE, Tokyo, Japan).

Image J was used to analyse the fluorescence signals40. The position of each cell was determined, and a time series of fluorescence signals was obtained from each cell.

Data processing

Data processing and analyses were performed using MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). Trend extraction and detrending were performed as follows: Glucose addition at 30 s caused large baseline shifts and perturbations in NADH fluorescence intensities, which lasted for 100 s at the longest. Therefore, the data until 100 s were removed because the shifts and perturbations interfered with the subsequent trend extraction.

The trends were extracted by moving median followed by moving mean. Moving mean is suitable for removing waves whose periods are equal to \(\:1/n\) of the sliding window. However, if the periods are \(\:1/(n+0.5)\) times of the window, the waves remain as counter-phase waves. This problem can be solved by performing the moving average twice, with the second window size being 1.5 times the first window size. Additionally, moving mean is good at smoothing but is sensitive to outliers, whereas moving median returns discrete line but is robust to outliers. Performing moving median prior to moving mean allows the best of both worlds. From the above, we extracted trends by performing moving median prior to moving mean, with the second window size being 1.5 times the first window size. Specifically, the MATLAB code is “mean(median(x, w), 1.5*w)”, where x and w are data and sliding window, respectively. The value for w was 30 s in this paper.

The short-time Fourier transform (STFT) was performed on the detrended data to obtain a series of discrete Fourier transforms (DFT). The spectral window and overlap were Hanning windows with window sizes of 64 s and 75%, respectively. Fisher’s G-test41, a significance test for the main frequency, was applied to each DFT with a p-value of 0.05.

Synchronisation analysis

The degree of synchronisation is characterised by the time-dependent order parameter K(t), defined as follows26:

where N is the total number of oscillatory cells, and \(\:{\theta\:}_{j}\left(t\right)\) is the phase of an oscillatory cell j in a complex plane. The order parameter is the normalised length of the vector sum of phase points, which quantifies the degree of phase synchronicity. Values of the order parameter close to unity indicate a high degree of synchronisation, whereas values close to zero indicate a low degree of synchronisation, large heterogeneities, and oscillations among individual cells.

Convergent cross mapping (CCM) analysis

The CCM estimates time series \(\:X\left(t\right)\) from the attractor of time series \(\:Y\left(t\right)\) when \(\:X\left(t\right)\) is the cause of \(\:Y\left(t\right)\). Specifically, it is as follows: (i) The \(\:E\)-dimensional attractor \(\:{M}_{Y}\) is constructed from \(\:Y\left(t\right)\) with \(\:y\left(t\right)=\left(\left(Y\left(t\right),\:Y(t-\tau\:\right),\:Y\left(t-2\tau\:\right),\:\dots\:,\:Y(t-\left(E-1\right)\tau\:)\right)\); (ii) Find the nearby points of \(\:y\left(t\right)\) as \(\:y\left({t}_{1}\right),\:y\left({t}_{2}\right),\:y\left({t}_{3}\right),\:\dots\:,\:y\left({t}_{E+1}\right)\) in ascending order on \(\:{M}_{Y}\) so that \(\:y\left(t\right)\) can be expressed by the weighted average of Euclid distance \(\:d\left(t,\:{t}_{i}\right)=\|y\left(t\right)-y\left({t}_{i}\right)\|\) between \(\:y\left(t\right)\) and \(\:y\left({t}_{i}\right)\), where \(\:i=1,\:2,\:3,\:\dots\:,\:E+1\); (iii) By using \(\:x\left({t}_{i}\right)\), which corresponds with \(\:y\left({t}_{i}\right)\), the estimated value \(\:\widehat{x}\left(t\right)\) for \(\:x\left(t\right)\) is calculated with arithmetic weighted average as

The estimated value \(\:\widehat{X}\left(t\right)\) for \(\:X\left(t\right)\) can be obtained from the first component of \(\:\widehat{x}\left(t\right)\); iv) The CCM coefficient, \(\:\rho\:\left(L\right)\), as a measure of the causality from \(\:X\left(t\right)\) to \(\:Y\left(t\right)\) is defined as the correlation coefficient

between \(\:\widehat{X}\left(t\right)\) and \(\:X\left(t\right)\) averaged over all possible \(\:L-\)point windows, where numerator is the covariance between \(\:\widehat{X}\left(t\right)\) and \(\:X\left(t\right)\), and \(\:\sigma\:\) is the standard deviation. If there is a causal relationship between the signals, \(\:\rho\:\) converges to a constant equal or less than one.

The software ”pyEDM (1.13.1.0)” package on python42 was used to calculate the CCM coefficient \(\:\rho\:\). Time-series data for a window of 100 s were used to calculate the CCM coefficients, and the data window was shifted forward to investigate the spatiotemporal development of causality. The investigated data were in the window \(\:w=[\left\{131+5\:\left(n-1\right)\right\}\:\text{s},\:\left\{230+5\:\left(n-1\right)\right\}\:\text{s}]\) by changing \(\:n=1\:\sim\:21\) with increments of 1. The embedded dimension was defined as \(\:E=2\) by confirming the convergence of \(\:\rho\:\) values with increasing the library size (window size) to 100 s. The number of oscillatory cells investigated was \(\:N=254\), and the CCM coefficients were calculated for 32,131 pairs of cells for each time window.

Notably, the first-time interval (131–230 s) for identifying causal interaction used in some cases (Figs. 2B and C, 4 and 5; Supplementary Figs. 7, 8, 9; Supplementary Table 1) was a methodological choice. Because the oscillatory behavior began to decrease from around 250 s, and the amplitude of oscillations became small after approximately 300 s in many cells (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, the analysed results showed that large clusters of causal networks decomposed with time, and their size became a quarter of the original size at approximately 230 s (Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Table 1). Thus, we selected the first-time interval during which most of the HeLa cells exhibited well-defined oscillations suitable for the analyses.

Surrogate test was carried out to confirm the reliability of calculated value \(\:\rho\:\); artificial time series data of glycolytic oscillations were created by inverting the data in the middle of time, and then \(\:\rho\:\) value was calculated by using the artificial time series (surrogate time series data). This surrogate time series was produced by “pyunicorn (0.6.1)” package on python from the original time series with twin surrogate method43. One hundred sets of surrogate time series were created from the original, and CCM analysis was performed for each surrogate datum, after which the 5 percentiles from the largest value in 100 results were determined as the CCM value of the surrogate data. This analysis was applied to the cell pairs whose CCM value was larger than 0.6 and checked if the CCM value of the original data was larger than that of the surrogate data (Surrogate Test). We observed that approximately 80% of the cell pairs passed the surrogate test if their original CCM value was greater than 0.8, whereas approximately 50% of the cell pairs passed the test if the original CCM value was between 0.6 and 0.8. Considering this result, we decided to use 0.8 for the threshold of the CCM value when we conduct the causal analysis based on the CCM value.

Complex network analysis

The network structure obtained from the CCM analysis was investigated as follows: the frequencies of the appearance of nodes (cells) as a function of their degrees (number of links) were examined, and double logarithmic values were plotted. When linear relationships with a slope of \(\:-\gamma\:\:(\gamma\:>0)\) were obtained, the distribution of degree of nodes followed a \(\:\gamma\:-\)th power law. In contrast, when the above plot can be fitted with a convex curve at the top, the distribution follows a Poisson distribution. In this case, the network structure was assumed to be stochastic. “network (3.0)” package for python was used to analyse the network structure44.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Armingol, E., Officer, A., Harismendy, O. & Lewis, N. E. Deciphering cell-cell interactions and communication from gene expression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 22, 71–88 (2021).

Ćáp, M., Štěpánek, L., Harant, K., Váchová, L. & Palková, Z. Cell differentiation within a yeast colony: metabolic and regulatory parallels with a tumor-affected organism. Mol. Cell. 46, 436–448 (2012).

Brooks, G. A. The science and translation of lactate shuttle theory. Cell. Metab. 27, 757–785 (2018).

Li, F. & Simon, M. C. Cancer cells don’t live alone: metabolic communication with tumor microenvironments. Dev. Cell. 54, 183–195 (2020).

Mächler, P. et al. In vivo evidence for a lactate gradient from astrocyte to neurons. Cell. Metab. 23, 94–102 (2016).

Nakajima, E. C. & Van Houten, B. Metabolic symbiosis in cancer: refocusing the Warburg lens. Mol. Carcinog. 52, 329–337 (2013).

Brooks, G. A. et al. Tracing the lactate shuttle to the mitochondrial reticulum. Exp. Mol. Med. 54, 1332–1347 (2022).

Weber, A., Prokazov, Y., Zuschratter, W. & Hauser, M. J. B. Desynchronisation of glycolytic oscillations in yeast cell populations. PLoS One. 7, e43276 (2012).

Weber, A., Zuschratter, W. & Hauser, M. J. B. Partial synchronization of glycolytic oscillations in yeast cell populations. Sci. Rep. 10, 19714 (2020).

Lancaster, G., Suprunenko, Y. F., Jenkins, K. & Stefanovska, A. Modeling chronotaxicity of cellular energy metabolism to facilitate the identification of altered metabolic States. Sci. Rep. 6, 29584 (2016).

Marinelli, I., Fletcher, P. A., Sherman, A. S., Satin, L. S. & Bertram, R. Symbiosis of electrical and metabolic oscillations in pancreatic b-cell. Front. Physiol. 12, 781581 (2021).

Richard, P. The rhythm of yeast. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27, 547–557 (2003).

Wolf, J. & Heinrich, R. Effect of cellular interaction on glycolytic oscillations in yeast: A theoretical investigation. Biochem. J. 345, 321–334 (2000).

MacDonald, P. & Rorsman, P. Oscillations, intercellular coupling, and insulin secretion in pancreatic b-cells. PLoS Biol. 4, e49 (2006).

Amaral, L. A. N., Scala, A., Barthélémy, M. & Stanley, H. E. Classes of small-world networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97, 11149–11152 (2000).

Strogatz, S. H. Exploring complex networks. Nature 410, 268–276 (2001).

Albert, R. & Barabási, A. L. Statistical mechanics of complex networks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 47–97 (2002).

Stožer, A. et al. Functional connectivity in Islets of Langerhans from mouse pancreas tissue slices. PloS Comput. Biol. 9, e1002923 (2013).

Johnston, N. R. et al. Beta cell hubs dictate pancreatic islet responses to glucose. Cell. Metab. 24, 389–401 (2016).

Briggs, J. K. et al. \(\:{\upbeta\:}\)-cell intrinsic dynamics rather than gap junction structure dictates subpopulations in the islet functional network. eLife 12, e83147 (2023).

Amemiya, T. et al. Primordial oscillations in life: direct observation of glycolytic oscillations in individual HeLa cervical cancer cells. Chaos 27, 104602 (2017).

Amemiya, T. et al. Glycolytic oscillations in HeLa cervical cancer cell spheroids. FEBS J. 289, 5551–5570 (2022).

Sugihara, G. et al. Detecting causality in complex ecosystems. Science 338, 496–500 (2012).

Park, J. & Sugihara, G. Pao Gerald. Control of complex systems with generalized embedding and empirical dynamic modeling. PloS One. 19, e0305408 (2024).

BozorgMagham, A. E., Motesharrei, S., Penny, S. G. & Kalnay, E. Causality analysis: identifying the leading element in a coupled dynamical system. PLoS One. 10, e0131226 (2015).

Shinomoto, S. & Kuramoto, Y. Phase transition in active rotator systems. Prog Theor. Phys. 75, 1105–1110 (1986).

Mojica-Benavides, M. et al. Intercellular communication induces glycolytic synchronization waves between individually oscillating cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 118, e2010075118 (2021).

Broid, A. D. & Clauset, A. Scale-free networks are rare. Nat. Commun. 10, 1017 (2019).

Rapisardi, G., Kryven, I. & Arenas, A. Percolation in networks with local homeostatic plasticity. Nat. Commun. 13, 122 (2022).

Van Rossum, G. & Drake, F. L. Python 3 reference manual. CreateSpace, Scotts Valley, CA (2009).

Zhang, S. Z. et al. Rapid measurement of lactate in the exhaled breath condensate: biosensor optimization and in-human proof of concept. ASC Sens. 7, 3809–3816 (2022).

Janiszewska, M., Primi, M. C. & Izard, T. Cell adhesion in cancer: beyond the migration of single cells. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 2495–2505 (2020).

Amemiya, T., Shibata, K. & Yamaguchi, T. Metabolic oscillations and glycolytic phenotypes of cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 11914 (2023).

Amemiya, T. et al. Collective and individual glycolytic oscillations in yeast cells encapsulated in alginate microparticles. Chaos 25, 064606 (2015).

Gustavsson, A. K., Adiels, C. B., Mehlig, B. & Goksör, M. Entrainment of heterogeneous glycolytic oscillations in single cells. Sci. Rep. 5, 9404 (2015).

Schütze, J., Mair, T., Hauser, M. J. B., Falcke, M. & Wolf, J. Metabolic synchronization by traveling waves in yeast cell layers. Biophys. J. 100, 809–813 (2011).

Tengholm, A. & Gylfe, E. Oscillatory control of insulin secretion. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 297, 58–72 (2009).

Šterk, M., Barać, U., Stožer, A. & Gosak, M. Both electrical and metabolic coupling shape the collective multimodal activity and functional connectivity patterns in beta cell collectives: A computational model perspective. Phys. Rev. E. 108, 054409 (2023).

Albert, R., Jeong, H. & Barabási, A. L. Error and attack tolerance of complex networks. Nature 406, 378–383 (2000).

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. NIH image to image J: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 9, 671–675 (2012).

Wichert, S., Fokianos, K. & Strimmer, K. Identifying periodically expressed transcripts in microarray time series data. Bioinformatics 20, 5–20 (2004).

Park, J. ‘https://github.com/SugiharaLab/pyEDM#readme’, Python Implementation of EDM Tools Developed at the Sugihara Lab., UCSD Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

Donges, J. F. et al. Unified functional network and nonlinear time series analysis for complex systems science: the Pyunicorn package. Chaos 25, 113101 (2015).

Hagberg, A., Swart, P. J. & Schult, D. A. Exploring network structure, dynamics, and function using networkx. United States. (2008). https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/960616

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI (grant numbers 19H04205 and 20K20631), MEXT Promotion of Distinctive Joint Research Center Program (grant number JPMXP0620335886), and a cooperative research project from Yokohama National University (YNU).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TA designed the study and wrote the manuscript; SS analysed the experimental results and wrote the manuscript; IF carried out the experiments; KS and KN analysed the data; MW interpreted the results; and TY interpreted the results and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 2

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amemiya, T., Shuto, S., Fujita, I. et al. Causal interaction of metabolic oscillations in monolayers of HeLa cervical cancer cells: emergence of complex networks. Sci Rep 15, 7423 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91711-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91711-8

This article is cited by

-

Deciphering the tumor immune microenvironment: single-cell and spatial transcriptomic insights into cervical cancer fibroblasts

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2025)