Abstract

To assess the prognostic value of preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-derived pelvic and prostatic parameters for long-term urinary continence (UC) following Retzius-sparing robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RS-RARP). 253 patients who underwent RS-RARP by a single surgeon were retrospectively collected for analyses. MRI parameters reflecting the transverse and anteroposterior diameters of the pelvis, as well as the depth of the prostate, were measured. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed to identify predictors of long-term UC. Immediate UC was achieved in 49.4% of patients, with cumulative rates increasing to 95.3% by 12 months postoperatively. Multivariate analysis identified age, tuberous width index (TWI), and clinical T3 stage as independent predictors of long-term UC after RS-RARP. The TWI, derived from preoperative MRI, is a novel predictor of long-term urinary continence following RS-RARP. Integration of TWI with established clinical parameters into a predictive model can aid in preoperative counseling and surgical planning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Radical prostatectomy (RP) is the primary treatment option recommended for patients with localized prostate cancer (PCa)1. However, postoperative urinary incontinence is a common concern among patients undergoing RP1, substantially impacting their quality of life2. Robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) has become the main surgical approach for RP3, owing to its minimally invasive nature, visual acuity and precision offered by robotic systems, which facilitate meticulous dissection and preservation of neurovascular bundles4. In 2010, Galfano et al. first described Retzius-sparing robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RS-RARP), which removes the prostate entirely through the rectovesical space while preserving important structures integral to UC5,6. This approach has been shown to significantly enhance immediate urinary UC and sustained long-term benefits over standard RARP7,8.

The prostate is situated deeply in the pelvic cavity, which presents challenges in terms of limited operational space for RP9,10. During RARP, the mechanical arms may collide or risk damaging the pelvic wall or other structures due to the confined pelvic space11. This limitation can be more significant in RS-RARP, where the operating space is more constrained. With the assistance of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), researchers have explored the impact of a “narrow pelvis” on the difficulty of RP. Notably, both the size of the pelvis and prostate12,13, as well as their relative positions9,10,14, significantly influence the complexity of RARP and postoperative outcomes. It is reasonable to hypothesize that a prostate located deep within a relatively narrow pelvis presents greater challenges for RS-RARP compared to those in a more spacious, shallow pelvis.

This retrospective study was designed to assess the relationship between prostate position and pelvis size with long-term UC after RS-RARP. Pelvic and prostatic parameters on MRI, as well as clinical parameters, were collected for analyses.

Patients and methods

Patients

From January 2018 to June 2023, patients with clinically localized or locally advanced PCa who underwent RS-RARP at our center by the same experienced surgeon (Dr. H.G) for RS-RARP (n > 500) were retrospectively collected. Patients with the following characteristics were excluded: (a) any prior neoadjuvant therapy; (b) any prior prostatic surgeries; (c) incomplete clinical, MRI or follow-up information; (d) obvious pelvic deformity that makes it impossible to measure pelvic and prostatic parameters on MRI images.

The perioperative data collected from our patient cohort included: age, body mass index (BMI), preoperative PSA levels, International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) grades of prostate biopsies, preoperative clinical T staging, the European Association of Urology (EAU) risk groups, the involvement of nerve-sparing during operation and the status of postoperative surgical margins. Biopsies were performed using a combination of targeted biopsy (for lesions with Prostate Imaging-Reporting and Date System [PI-RADS] score > 2 detected on multiparametric MRI) and systematic biopsy to ensure comprehensive evaluation of prostate pathology.

MRI pelvic-prostatic measurements

The MRI examinations were performed using a 3.0-Tesla scanner (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) with a pelvic phased-array coil for superior image resolution. The protocol included T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) in the sagittal, and axial planes, which provided detailed anatomical information of the prostate and surrounding pelvic structures. Specific details of the MRI protocol were available in supplementary materials. Pelvic-prostatic parameters were measured using the PACS/RIS software developed by Neusoft Group, which encompasses both the Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) and the Radiology Information System (RIS). The measurements were conducted by two experienced urologists M.C and X.L, who were blinded to the patients’ clinical, oncological characteristics, and prognostic outcomes. The measurement process was supervised by a radiologist, Dr. D.L. According to previous studies9,10,11,12,14, the parameters of interest were defined and measured as follows:

Parameters reflecting transverse width of the pelvis and prostate measured on axial T2WI (Fig. 1):

-

(1)

Interspinous distance (ISD): the narrowest distance between the ischial spines. (Fig. 1a)

-

(2)

Intertuberous distance (ITD): the widest distance between ischial tuberosities. (Fig. 1b)

-

(3)

Angle of the symphysis pubis (ASP) was also measured at the level where ITD was measured. (Fig. 1b)

-

(4)

Bony femoral width (BFW): the bony pelvic width at the mid-femoral head level. (Fig. 1c)

-

(5)

Soft tissue width (SW): the narrowest distance between the levator muscles. (Fig. 1d)

-

(6)

Prostate width (PW): the maximum width of the prostate. (Fig. 1e)

Parameters reflecting anteroposterior diameter of the pelvis on mid-sagittal T2WI (Fig. 2):

Axial and sagittal MRI of the pelvis on T2WI. (a) the interspinous distance (ISD): the narrowest distance between the ischial spines. (b) the intertuberous distance (ITD): the widest distance between ischial tuberosities. Angle of the symphysis pubis (ASP) was also measured. (c) the bony femoral width (BFW): the bony pelvic width at the mid-femoral head level. (d) the soft tissue width (SW) : the narrowest distance between the levator muscles. (e) the prostate width (PW): the maximum width of the prostate.

Sagittal MRI of the pelvis on T2WI. (a) API: anteroposterior distance of the pelvic inlet, the distance from the sacral promontory to the upper edge of the pubic symphysis. APM: anteroposterior distance of the pelvic midplane, the shortest distance from the inferior edge of the pubic symphysis to the sacrococcygeal junction. APO: anteroposterior distance of the pelvic outlet, the distance from the inferior edge of the pubic symphysis to the tip of the coccyx. PD: pelvic depth, the distance from the sacral promontory to the inferior edge of the pubic symphysis. (b) AD: apical depth, the craniocaudal distance from the level of the superior edge of the pubic symphysis to the level of the prostate apex. (c) PH: prostate height, the craniocaudal distance from the level of the superior edge of the prostate to the level of the prostate apex. (d) Presence of median lobe.

-

(1)

Anteroposterior distance of the pelvic inlet (API): the distance from the sacral promontory to the upper edge of the pubic symphysis. (Fig. 2a)

-

(2)

Anteroposterior distance of the pelvic midplane (APM): the shortest distance from the inferior edge of the pubic symphysis to the sacrococcygeal junction. (Fig. 2a)

-

(3)

Anteroposterior distance of the pelvic outlet (APO): the distance from the inferior edge of the pubic symphysis to the tip of the coccyx. (Fig. 2a)

-

(4)

Pelvic depth (PD): the distance from the sacral promontory to the inferior edge of the pubic symphysis. (Fig. 2a)

-

(5)

The parameter reflecting the depth of the prostate was AD, which was defined as the craniocaudal distance from the level of the superior edge of the pubic symphysis to the level of the prostate Fig. (Fig. 2b). Prostate height (PH) was defined as the craniocaudal distance from the level of the superior edge of the prostate to the level of the prostate Fig. (Fig. 2c). Presence of median lobe was also confirmed on sagittal Fig. (Fig. 2d.). PV was estimated using the ellipsoid formula as follows: PV = width × length × heigh × (π/6).

Pelvic dimension index (PDI) was defined as ISD/AD. Bony width index (BWI) was defined as BFW/AD. Soft tissue width was defined as SW/AD. And the novel index, Tuberous width index (TWI), was defined as ITD/AD. Besides, we also assessed the percentage of prostate occupying the pelvis diameter using BFW/PW, SW/PW and PD/PH.

RS-RARP and postoperative care

All patients underwent RS-RARP, utilizing the 4-arm da Vinci Surgical System, following the protocol described by Galfano et al. and Lim et al.5,15. The decision to perform unilateral or bilateral nerve-sparing procedures was based on the patient’s preoperative baseline conditions and the lesion characteristics revealed by preoperative MRI. All patients had an appropriately sized Foley catheter indwelling postoperatively, which was removed between 7 and 9 days after surgery. And patients were discharged between 4 and 6 days postoperatively.

Follow up and continence evaluation

All patients were educated in the performance of Kegel exercises and were encouraged to adopt these to enhance the recovery of UC. Immediate UC was assessed 7days after catheter removal, with subsequent telephone follow-ups to evaluate UC status at 1, 2, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months postoperatively. UC was defined as the use of 0 pad per day.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were described as median (interquartile range, IQR). And categorical variables were described as frequency. We utilized univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses to assess the association between long-term UC and all variables. Variables with a P value < 0.05 in the multivariate analysis were selected for survival curve estimation using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Continuous variables were dichotomized at specific cut-off points based on receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. Significant variables with a P value < 0.05 were used to construct a multivariate Cox model. To visualize this model, we developed a nomogram to predict immediate UC and UC at 3, 6, and 12months post-surgery. Subsequently, we assessed the performance of the Cox model and each significant variable using time-dependent area under the ROC curve (AUC). Calibration curves were employed to evaluate whether the model’s predictions of postoperative UC were overly optimistic or pessimistic, and internal validation was performed using bootstrapping with 1000 iterations. Additionally, we conducted decision curve analysis (DCA) to assess the clinical utility of the model. Statistical analyses and visualizations were carried out using SPSS software (version 29.0) and R software (version 4.4.1). All tests were two-sided, with a P value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

General information

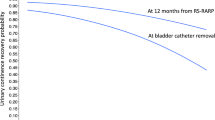

A total of 253 patients were eligible for this study. A detailed patient screening process is depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1. Patients’ baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The median BMI was 24.38 (IQR: 22.62–26.32), and the median age was 68 years (IQR: 64–73). MRI-derived pelvic and prostatic parameters are also detailed in Table 1. The median TWI was 2.73 (IQR: 2.38–3.14), and the median ASP was 67° (IQR: 61–72). The recovery of UC over time is presented in Supplementary Fig. 2. Immediate UC was achieved in 125 patients (49.4%). The cumulative percentage of patients achieving UC increased to 63.2% at 1 month, 73.9% at 2 months, 79.4% at 3 months, and 95.3% at 12 months after RS-RARP, respectively.

Cox regression analysis for long term UC

Univariate and multivariate cox regression were performed to identify predictors associated with long-term UC. As shown in Table 2, age, SW, AD, PDI, BWI, TWI, SW/PW, clinical T3 stage, locally advanced PCa and nerve-sparing were found to be significantly correlated with long-term UC in univariate analysis. And in the multivariate analysis, age (odds ratio, OR: 0.978, 95% confidence interval, CI: 0.958–0.998, P = 0.028), TWI (OR: 1.627, 95%CI: 1.268–2.008, P < 0.001) and clinical T3 stage (OR: 0.473, 95%CI: 0.294–0.761, P = 0.002) remained independent predictors for long-term UC. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were constructed to assess long-term UC based on the optimal cut-off values determined by the ROC curve for TWI and age (Fig. 3). The curves demonstrate significant differences in long-term UC among populations stratified by these variables. Similarly, patients with clinical T3 stage PCa exhibited significant longer time to achieve UC, as illustrated by the survival curves.

We have categorized the patients based on high TWI and low TWI to compare outcomes that measure surgical difficulty, including operating time, estimated blood loss, and positive surgical margin rate. The results are presented in Supplementary Table 2. In patients with a ‘narrow pelvis,’ there was significantly more blood loss, but there was no significant difference in operating time or the rate of positive surgical margins.

Construction and validation of the Cox model

A nomogram incorporating TWI, age, and clinical T stage was developed to predict immediate UC, as well as UC at early (3-month), mid-term(6-month), and long-term (12-month) follow-up periods after RS-RARP (Fig. 4). Supplementary Fig. 3 showed the AUC values across different follow-up time points for UC. The analysis showed that the cox model provides superior predictive value compared to individual parameters. Calibration curves for the cox model, depicted in Supplementary Fig. 4, demonstrated the predictive performance of the nomogram for immediate, early, mid-term and long-term UC. DCA for UC at different time points indicated the clinical utility of the model in guiding patient management (Supplementary Fig. 5).

To further validate the predictive model, we specifically analyzed the subset of patients with a Gleason score of 3 + 3. The results indicated that long-term urinary continence in this subset is still influenced by pelvic- prostatic parameters. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for long-term UC in patients with a Gleason score are presented in Supplementary Fig. 6. Calibration curves for the predictive model in this subset are shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. These analyses confirm the robustness of our predictive model across different patient groups.

Discussion

Under the hypothesis that a “narrow pelvis” impacts the difficulty of RS-RARP, the aim of the present study was to investigate the predictors for long-term UC following RS-RARP, and to subsequently develop and validate predictive model based on these factors. Our cox regression model exhibits relatively robust discriminatory and calibration capabilities. Furthermore, DCA indicates that across a broad range of threshold probabilities, the model yields higher net benefits compared to both treat-all and treat-none strategies, suggesting its potential to aid in clinical decision-making.

Matikainen et al. used indices including PDI, BWI and SWI to assess the “difficulty” of the pelvis and found that lower PDI, BWI and SWI values were associated with an increased risk of apical PSM after open retropubic RP and LRP9. Inspired by these findings, we defined a new parameter, TWI, defined as the ratio of ITD to AD, and aimed to identify which parameter derived from the ratio of pelvic transverse diameter by the AD, is most applicable in the context of RS-RARP. The Cox regression analysis and the Kaplan-Meier survival curves confirm the predictive value of TWI, indicating that patients with a higher TWI demonstrate a more favorable prognosis for long-term UC. This suggests the spatial relationship between the prostate and the bony pelvis, as reflected by the TWI, does have impact the difficulty of performing RS-RARP, thereby affecting postoperative UC. This may be associated with the restricted maneuvering space for key steps related to UC, such as neurovascular bundle preservation, maximal urethral length preservation, bladder neck preservation and posterior reconstruction. However, PV was not identified as a predictor for long-term UC after RS-RARP, which aligns with previous notions that large-volume prostates may negatively impact immediate UC following RS-RARP but have no significant effect on long-term urinary control16. These findings suggests that for the long-term prognosis of RS-RARP, we should not consider only the size of the pelvis or prostate but should instead take into account both size and relative position in a comprehensive manner. In this study, the immediate UC rate in patients who underwent RS-RARP was lower than that reported in previous studies6,17, which is likely attributed to the inclusion of T3-stage patients. This finding is further corroborated by the survival curves (Fig. 3c). RP in patients with T3-stage disease is associated with a higher rate of positive surgical margins1. To achieve better tumor control in these cases, surgeons may use nerve-sparing techniques less frequently or perform more extensive resections18,19, which could result in greater damage to the surrounding muscle structures. We hypothesize that the inferior postoperative UC recovery observed in these patients could be related to these surgical considerations.

The limitations of this study lie in its single-center, retrospective nature, which may restrict its generalizability. The lack of external validation is a significant limitation, as external validation is essential for the prediction tool to be used in clinical practice. Future studies should focus on external validation to confirm the robustness of our predictive model across different populations and settings. However, it is important to note that our surgical team has extensive experience with the Retzius-sparing approach, having completed over 500 cases prior to the inclusion of patients in this study. This experience allows us to minimize the impact of the learning curve and ensure that the results are not biased by surgical technique immaturity. Due to the poor baseline conditions, this study did not explore postoperative sexual function outcomes. Future studies could investigate the impact of pelvic factors on RS-RARP outcomes across different ethnicities, as previous reports have shown higher rates of positive apical surgical margins in African American men20, speculated to be related to the narrower pelvic anatomy in African males. Additionally, subsequent research could focus on the long-term oncological impact of pelvic-prostate factors following RS-RARP to better answer how ‘narrow pelvis’ affects patients undergoing RS-RARP.

RS-RARP is a surgical technique that can improve postoperative urinary control compared to traditional RARP. Early studies regarded this procedure as technically challenging; however, recent, likely due to advancements in surgical techniques, has shown that RS-RARP does not compromise in terms of outcomes such as console time, estimated blood loss, and tumor control6,7. Previous studies have demonstrated that, aside from longer console time, surgeons early in their learning curve can achieve outcomes comparable to those of experienced surgeons21. This suggests that RS-RARP is a viable option that can be confidently chosen by surgeons and patients. In previous studies on ‘narrow pelvis’, pelvic-prostatic parameters did not significantly affect early postoperative UC in traditional RARP11,13. Boczko et al. reported a UC rate of 66.6% at 3 months post-RARP11, whereas in our study, among patients with a low TWI (TWI ≤ 2.5), only 45 individuals (58.4%) achieved UC at the same time point. Therefore, we consider that patients with a ‘narrow pelvis’ may be better suited for traditional RARP. This study focuses on the impact of ‘narrow pelvis’ on RS-RARP outcomes, providing a reference for physicians and patients considering RS-RARP. It allows all participants to better weigh and choose surgical strategies.

In conclusion, our study developed a novel pelvic-prostatic parameter, TWI, and identified that lower TWI was associated with worse long-term UC following RS-RARP. This provides a novel perspective for the understanding of pelvic anatomy in RS-RARP, emphasizing that both the size and relative positioning of the prostate within the pelvic cavity are crucial factors influencing surgical outcomes. Integration of TWI with established clinical parameters into a predictive model can aid in preoperative counseling and surgical planning. Future studies should focus on long-term oncological outcomes, and the impact of pelvic factors on different populations.

Data availability

The data sets utilized in this research are currently not accessible to the public due to the continuation of related clinical trials that are leveraging the identical data set. However, these data can be provided by the corresponding author, X.Q., upon a legitimate scientific request.

Change history

03 June 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in Affiliation 1, which was incorrectly given as ‘Department of Urology, Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University, Nanjing, 210008, China’. The correct affiliation is listed here: ‘Department of Urology, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Medical School, Nanjing University, Nanjing, 210008, China’. The original Article has been corrected.

References

Cornford, P. et al. Guidelines on prostate Cancer—2024 update. Part I: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur. Urol. 86, 148–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2024.03.027 (2024). EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG.

Liss, M. A. et al. Continence definition after radical prostatectomy using urinary quality of life: evaluation of patient reported validated questionnaires. J. Urol. 183, 1464–1468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2009.12.009 (2010).

Coughlin, G. D. et al. Robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy versus open radical retropubic prostatectomy: 24-month outcomes from a randomised controlled study. Lancet Oncol. 19, 1051–1060. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(18)30357-7 (2018).

Haney, C. M. et al. Robot-assisted versus conventional laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: A systematic review and Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur. Urol. Focus. 9, 930–937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2023.05.007 (2023).

Galfano, A. et al. A new anatomic approach for Robot-Assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy: A feasibility study for completely intrafascial surgery. Eur. Urol. 58, 457–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2010.06.008 (2010).

Umari, P. et al. Retzius-Sparing versus standard Robot-Assisted radical prostatectomy: A comparative prospective study of nearly 500 patients. J. Urol. 205, 780–790. https://doi.org/10.1097/ju.0000000000001435 (2021).

Egan, J. et al. Retzius-sparing Robot-assisted radical prostatectomy leads to durable improvement in urinary function and quality of life versus standard Robot-assisted radical prostatectomy without compromise on oncologic efficacy: Single-surgeon series and Step-by-step guide. Eur. Urol. 79, 839–857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2020.05.010 (2021).

Dalela, D. et al. A pragmatic randomized controlled trial examining the impact of the Retzius-sparing approach on early urinary continence recovery after Robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Eur. Urol. 72, 677–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2017.04.029 (2017).

Matikainen, M. P. et al. The depth of the prostatic apex is an independent predictor of positive apical margins at radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 106, 622–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.09184.x (2010).

Lu, H. et al. Effects of bony pelvic and prostate dimensions on surgical difficulty of Robot-Assisted radical prostatectomy: an original study and Meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-024-15769-w (2024).

Boczko, J., Erturk, E. & Joseph, J. V. Is there a proper pelvic size for an extraperitoneal Robot-Assisted radical prostatectomy?? J. Endourol. 21, 1353–1356. https://doi.org/10.1089/end.2007.9898 (2007).

Hong, S. K. et al. Effect of bony pelvic dimensions measured by preoperative magnetic resonance imaging on performing robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy. BJU Int. 104, 664–668. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08624.x (2009).

Kimura, N. et al. The ‘prostate-muscle index’: a simple pelvic cavity measurement predicting estimated blood loss and console time in robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Sci. Rep. 12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-16202-6 (2022).

von Bodman, C. et al. Do pelvic dimensions and prostate location contribute to the risk of experiencing complications after radical prostatectomy? BJU Int. 108, 1566–1571. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.010171.x (2011).

Lim, S. K. et al. Retzius-sparing robot‐assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: combining the best of retropubic and perineal approaches. BJU Int. 114, 236–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.12705 (2014).

Galfano, A. et al. Does prostate volume have an impact on the functional and oncological results of Retzius-sparing robot-assisted radical prostatectomy? Minerva Urol. Nefrol. 70 https://doi.org/10.23736/s0393-2249.18.03069-2 (2018).

Qiu, X. et al. Retzius-sparing robot‐assisted radical prostatectomy improves early recovery of urinary continence: a randomized, controlled, single‐blind trial with a 1‐year follow‐up. BJU Int. 126, 633–640. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.15195 (2020).

Gözen, A. S., Akin, Y., Ates, M., Hruza, M. & Rassweiler, J. Impact of laparoscopic radical prostatectomy on clinical T3 prostate cancer: experience of a single centre with long-term follow‐up. BJU Int. 116, 102–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.12710 (2015).

Engesser, C. et al. 3D-printed model for resection of positive surgical margins in robot‐assisted prostatectomy. BJU Int. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.16595 (2024).

Rabbani, F. et al. Impact of ethnicity on surgical margins at radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 104, 904–908. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08550.x (2009).

Olivero, A. et al. Retzius-sparing robotic radical prostatectomy for surgeons in the learning curve: A propensity Score–matching analysis. Eur. Urol. Focus. 7, 772–778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2020.03.002 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82172639, 81972388, 82303895), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK 20210023),the Project of Invigorating Health Care through Science, Technology and Education, Jiangsu Provincial Key Medical Discipline (Laboratory) (ZDXKB2016014), and Nanjing Medical Science and technique Development Foundation (QRX17128).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.G., J.N. and X.Q.: project development. J.N.: manuscript writing. H.G. and X.Q.: manuscript editing. X.L. and M.C.: technical and material support. J.N., J.S. and M.C.: data management. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This retrospective study involving human participants was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. And it was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Drum Tower Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Niu, J., Chen, M., Lyu, X. et al. Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging pelvic and prostatic parameters predict long-term urinary continence after Retzius-sparing robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Sci Rep 15, 13543 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91837-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91837-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Preoperative pelvimetric and prostatic measurements as predictors of intraoperative blood loss in open transvesical prostatectomy: a retrospective study

BMC Surgery (2025)

-

Construction of a nomogram model for clinically significant prostate cancer based on biparametric magnetic resonance imaging

International Urology and Nephrology (2025)