Abstract

Transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) is an efficient neuromodulation technique to enhance cognitive function in a non-invasive manner. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging, we investigated whether a cross-frequency coupled tACS protocol with a phase lag (45 and 180 degrees) between the central executive and the default mode networks modulated working-memory performance. We found tACS-phase-dependent modulation of task performance reflected in hippocampal activation and task-related functional connectivity. Our observations provide a neurophysiological basis for neuromodulation and a feasible non-invasive approach to selectively stimulate a task-relevant deep brain structure. Overall, our study highlights the potential of tACS as a powerful tool for enhancing cognitive function and sheds light on the underlying mechanisms of this technique.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Working memory is a cognitive system with limited capacity that enables us to temporarily retain information and focus our attention on a specific mental representation1. As a fundamental cognitive process, working memory plays a critical role in human behavioral performance. Non-invasive neuromodulation techniques aimed at enhancing working memory have the potential to significantly improve overall cognitive function. However, recent studies attempting to increase working-memory capacity have yielded controversial results, possibly due to protocol discrepancies and a lack of understanding regarding the underlying neurophysiological mechanisms2,3,4,5.

In recent years, neuromodulatory approaches aimed at enhancing cognitive function have undergone multiple adjustments in an effort to identify reliable and robust methods consistent with their neurophysiological bases6,7,8,9. One approach that has attracted renewed attention is non-invasive brain stimulation, which has shown promise as both a means of cognitive augmentation and a potential alternative to conventional therapies due to its safe and innovative nature. For instance, the successful use of transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) for neuromodulation in cognition and memory has been consistently demonstrated in recent studies5,10,11,12,13. It is presumed that tACS sinusoidally alters the transmembrane potential at the cellular level, and this effect is amplified through neurons that are synaptically connected14. This effect may underlie the tACS-mediated neuromodulatory mechanism leading to the entrainment and amplification of endogenous neuronal oscillations15,16,17,18,19. As a result, these sinusoidal transmembrane potential modulations may drive the resonation of one spectral activity by another in cases when oscillations approximately align.

In addition, neuromodulatory effects may have broader implications for neuronal oscillatory processes, as in the case of cross-frequency coupling (CFC), which reflects a specific interplay between large ensembles of neurons20. For instance, multiple-memory activity patterns can be encoded in a single neural network that shows nested oscillations, and these bear a similarity to those observed in the human brain21. The work of Canolty et al.22 demonstrated a CFC between theta and gamma oscillations during working-memory operations, supporting this model. Temporal segmentation, with each memory being stored in a different high-frequency subcycle of a low-frequency oscillation, theoretically provides a principal framework for the maintenance of multiple working-memory items. For example, it has been proposed that the number of gamma cycles per theta cycle determines the buffer’s working-memory capacity23, with the number of nested theta/gamma subcycles possibly accounting for the approximate number of items held in working memory21,24.

The human brain is intrinsically organized into distinct functional networks supporting cognitively different demanding processes25,26,27,28. Analysis of resting-state functional connectivity has suggested the existence of at least three canonical networks29: (1) a central-executive network (CEN), which includes the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) and posterior parietal cortex (PPC); (2) a default-mode network (DMN), whose key nodes include the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC); and (3) a salience network (SN), which includes the anterior insula (AI) and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). The anti-correlated relationship between CEN and DMN during most cognitive functions is well known (Fig. 1)29,30. For instance, during the performance of cognitively demanding tasks, cognitive states that activate the CEN typically deactivate the DMN and vice versa25,26,31. The dynamics of switching between these two networks are controlled via the SN, which is involved in recruiting relevant functional networks30,32,33. It is widely accepted that coordination of the mutually antagonistic CEN and DMN plays a key regulatory role in organizing the neural responses underlying fundamental brain functions34.

Our tACS-mediated neuromodulatory experimental design utilized this anti-correlated relationship between CEN and DMN. We applied tACS with a multi-electrode setup, which can be used to investigate how oscillatory coherence between spatially distinct nodes of functional networks underlies behavior. This method allows for the simultaneous application of oscillatory currents over different regions at the same frequency, but with different oscillatory phases, facilitating or hampering synchronization in functional networks35,36,37,38. We administered tACS to the core nodes of two anti-correlated networks (i.e., CEN and DMN) with a specific phase lag (either 45° or 180° between CEN and DMN) to induce facilitation or inhibition in task performance, respectively.

Specifically, we hypothesized that the neuromodulatory effect of targeting the brain oscillations responsible for working memory would be maximized when (i) the stimulation wave resembled the target wave (i.e., human brain theta/alpha/gamma oscillations) as closely as possible, and (ii) an optimal phase lag was applied between CEN and DMN. To address the first point, the present study employed an individually customized theta-alpha phase and high-gamma-amplitude tACS to influence cross-frequency coupling (CFC), focusing on the participants’ endogenous oscillations. Since working-memory performance involves frontal theta activity39,40,41 and fronto-parietal theta synchronization5,42,43, and alpha activity generally reflects cortical inhibition44,45,46, we hypothesized that individually customized theta or alpha peak-coupled CFC-formed tACS might strengthen its influence on working memory. To address the second point, we adapted a previous study that found that phase differences (\(\:{\Delta\:}\phi\:\)) of approximately 45° (optimally partially in-phase) and 180° (anti-phase) between the tACS oscillatory activity in the fronto-polar and parietal electrodes yielded the best and worst performance during a decision-making task, respectively38. Therefore, we applied CFC-formed tACS with phase lags of either 45° or 180° between CEN and DMN to examine its phase dependency in cognitive control47,48,49,50. In addition, previous studies have shown that the effects of non-invasive electrical stimulation on working memory vary depending on participants’ task performance levels5,51,52,53,54. For example, applying 8-Hz tACS to the prefrontal region can effectively improve working memory performance (especially in individuals with low ability)51. Therefore, the present study also aims to investigate the effects of tACS on working memory by categorizing participants based on their task performance abilities.

Triple network model. The anti-correlated relationship between the central executive network (CEN; red regions) and default mode network (DMN; blue regions), which are regulated by the salience network (SN; green regions). rPFC rostral prefrontal cortex, ACC anterior cingulate cortex, aINS anterior insula, SMG supramarginal gyrus, dlPFC dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, PPC posterior parietal cortex, mPFC medial prefrontal cortex, HC hippocampus, PCC posterior cingulate cortex, pMTG posterior middle temporal gyrus, PrCu precuneus.

Results

Human participants (N = 26) conducted a modified Sternberg working-memory task55 (Fig. 2A and B) while we collected functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data and applied a network-wise cross-frequency tACS protocol to modulate their brain activity. The stimulation targets were the right/left PPC and right/left dlPFC for the CEN, and the mPFC and PCC for the DMN (Fig. 2C, also see Fig. 8 for the tACS channel montage). Each target was neuromodulated with a stimulation signal that had a combined theta/alpha-phase and high-gamma-amplitude coupled pattern, with frequencies individually selected based on the peaks of subject-specific power spectra on EEG data collected before the main experiment (see Eqs. (1) and (2)). The CEN and DMN stimulation targets were modulated with a tACS phase-lag of \(\:{\Delta\:}\phi\:\). Among the \(\:{\Delta\:}\phi\:\) values that could potentially facilitate or suppress task performance, we used 45 degrees as the optimal partially in-phase lag and 180 degrees as the out-of-phase lag, respectively, between the CEN and DMN regions in the present study (Fig. 2C). The tACS neuromodulation was applied only during the retention period of the Sternberg task. The experimental design included five consecutive fMRI runs of the Sternberg task with: (1) no tACS, (2) 45°-phase-lag CFC-tACS, (3) no tACS, (4) 180°-phase-lag CFC-tACS, and (5) no tACS. The order of the 45°- and 180°-phase-lag CFC-tACS sessions was counterbalanced across participants. Since neuromodulation effects have been shown to depend on task difficulty and the participant’s ability to improve on a task, participants were divided into two groups, the Slow Group and the Fast Group, based on the median split of the individual mean reaction times during the first fMRI run without tACS. This is because we anticipated different tACS effects depending on initial performance56,57,58,59: Low performers may potentially improve, whereas high performers have limited space to improve (saturated performance), though they can get worse. Data from six participants were excluded from analyses due to excessive head motion during fMRI.

Experimental design with the Sternberg working-memory task and tACS neuromodulation. (A) The Sternberg task was repeatedly applied to the same participant during, before, and after 45°-phase-lag and 180°-phase-lag tACS, with the order counterbalanced across participants. The tACS was applied only during the retention period of the Sternberg task. (B) We used a modified Sternberg task with a 7-item memory load. During the encoding phase, seven letter-numeral combinations were visually presented consecutively on the display monitor for 700 ms with an inter-stimulus interval (ISI) of 150 ms. This was followed by a 9-s retention period before the onset of a retrieval (probe-test) phase that was cued by a 1-s auditory beep. Participants were instructed to respond as fast as possible by pressing buttons indicating whether the probe item was part of the memory set presented during the encoding phase. Visual feedback was provided immediately after each response. (C) tACS neuromodulation with a phase lag between the CEN and DMN nodes. Cortical maps (lateral and medial views in the left panel) show the simulated neuromodulation of the tACS target areas during the peak stimulation of the CEN network (i.e., x-axis at π/2; vertical dotted lines in the right panel). The electric current intensities (mA) were scaled to be equal across CEN and DMN. Cross-frequency coupled tACS was applied with multi-electrode setups designed to modulate DMN (mPFC and PCC) with a phase lag of 45° (time course in blue) or 180° (time course in green) preceding that of CEN (dlPFC and PPC, time course in red). Color scales indicate the intracranial electric field (V/m), with high intensity in red and low intensity in blue.

Behavioral effects of CFC-tACS

We observed significant differences in the reaction times of the Sternberg task due to the tACS neuromodulation (Fig. 3A). Specifically, in the Fast Group, the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition yielded a significant increase in reaction times compared to (i) the no-tACS condition (t(9) = − 2.98, p = 0.016, FDR-corrected; 180°-phase-lag tACS: 758.36 ms; no-tACS before-treatment: 691.88 ms) and (ii) the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition (t(9) = − 2.93, p = 0.017, FDR-corrected; 45°-phase-lag tACS: 690.80 ms). There were no significant differences between the no-tACS and 45°-phase-lag tACS conditions (t(9) = 0.072, p = 0.944, FDR-corrected). In the Slow Group, we found no significant differences in reaction times due to tACS neuromodulation (no-tACS vs. 45°-phase-lag tACS: t(9) = 1.96, p = 0.082, FDR-corrected; no-tACS vs. 180°-phase-lag tACS: t(9) = 1.35, p = 0.211, FDR-corrected; 45°-phase-lag tACS vs. 180°-phase-lag tACS: t(9) = − 0.24, p = 0.816, FDR-corrected). In both the Fast and Slow Groups, we found no statistically significant differences in task performance accuracy due to tACS neuromodulation (See Supplementary Fig. S1).

Neural effects of CFC-tACS

The random-effects analysis of fMRI data revealed significant stimulation effects. Specifically, during the Sternberg task, the PCC was significantly more activated in the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition (across-tACS-condition analysis, both groups; Fig. 3B). This suggests that the DMN network remained more engaged in the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition. The within-tACS-condition analysis yielded consistent findings (Supplementary Fig. S2 and Table S1). As expected, the Sternberg task had the effect of suppressing DMN activity, particularly in the PCC (retention < rest). However, tACS neuromodulation counteracted this effect. Specifically, the suppression of PCC activity was more pronounced in the no-tACS condition, followed by the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition, and then by the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition, in which there was no longer any suppression. The effect was more evident in the Fast than the Slow Group.

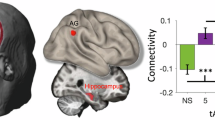

The full factorial analysis yielded a significant interaction effect between Group and Stimulation factors. The hippocampus in the right hemisphere exhibited significantly higher activation in the Fast Group than the Slow Group during the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the no-tACS condition (Fig. 3C).

Behavioral data and phase-lag tACS-mediated brain-activated regions. (A) Phase-lag tACS-mediated mean reaction times of the Fast and Slow Groups during the Sternberg task. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05, FDR-corrected). Error bars indicate standard errors of the mean. (B) The posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) was significantly more activated in the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition (cluster size: 209 voxels). (C) Interaction effects between Group and Stimulation. The right hippocampus was significantly more activated in the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the no-tACS condition in the Fast Group compared to the Slow Group (cluster size: 203 voxels; fMRI voxel-level threshold of p < 0.001 and a cluster-level family-wise error of p < 0.05).

Functional connectivity analyses revealed significantly higher connections during the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition in all three networks (i.e., CEN, DMN, and SN) compared to the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition (Fig. 4; Table 1). Additionally, Supplementary Fig. S5 shows brain regions where functional connectivity was greater in the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the no-tACS condition, as well as in the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the no-tACS condition. Regarding the DMN, using the right hippocampus as the seed for functional connectivity analysis led to the activation of the right anterior insula in the SN network for the Fast Group (Fig. 4A). In turn, when the right anterior insula was used as the seed, we observed activation of the posterior middle temporal gyrus (pMTG), a DMN node, in the same hemisphere for the Fast Group, and activation of the precentral gyrus in the SN network for the Slow Group (Fig. 4C; top segment). Notably, when the rostral prefrontal cortex (rPFC), an SN node, was used as the seed in either hemisphere, we observed the activation of the pMTG in the left hemisphere only for the Fast Group (Fig. 4C; middle and bottom segments). Regarding the CEN, using the right dlPFC as the seed for functional connectivity analysis led to the pronounced activation of the ventral precuneus, a DMN node, in both hemispheres only for the Fast Group (Fig. 4B). On the other hand, using the bilateral mPFC, a DMN node, as the seed led to the activation of the dorsal precuneus, a DMN node, only for the Fast Group (Fig. 4A; bottom segment). Furthermore, for the Fast Group, using the rostral PFC, an SN node, as the seed led to the activation of the fusiform gyrus in the left hemisphere, whereas using the same seed in the right hemisphere led to the activation of the lingual gyrus in both hemispheres. However, we did not observe any significant differences in functional connectivity for the Slow Group in these conditions.

A direct comparison between the Fast and Slow Groups was conducted (Fig. 4). Regarding the DMN, when the right hippocampus was used as the seed, the Fast Group exhibited higher functional connectivity than the Slow Group in the right anterior insula, caudate, middle frontal gyrus, and brainstem. Conversely, the Slow Group showed higher functional connectivity in the left hippocampus. Using the bilateral mPFC as the seed, the Fast Group demonstrated significantly higher functional connectivity in the right precuneus and cerebellum, with no regions showing significantly higher connectivity for the Slow Group. For the CEN, when the right dlPFC was used as the seed, the Fast Group exhibited significantly higher functional connectivity in the right precuneus compared to the Slow Group. Regarding the SN, when the right anterior insula was used as the seed, the Fast Group showed significantly higher functional connectivity in the left superior/middle temporal gyrus, superior temporal gyrus (temporal pole), hippocampus, thalamus, Heschl’s gyrus, cerebellum, and brainstem, as well as in the right superior temporal gyrus and superior temporal gyrus (temporal pole). In contrast, the Slow Group exhibited significantly higher functional connectivity in the right middle frontal gyrus and supplementary motor area. Finally, when the rostral PFC was used as the seed, the Fast Group showed higher functional connectivity in the left fusiform gyrus, cerebellum, vermis, superior temporal gyrus (temporal pole), lingual gyrus, the right precuneus, and inferior occipital gyrus. However, the Slow Group exhibited higher functional connectivity in the left supplementary motor area. Taken together, increased functional connectivity during the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition was predominantly observed in the Fast Group rather than in the Slow Group.

Functional connectivity in the DMN, CEN, and SN. Brain regions where functional connectivity was greater for the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition. Results shown separately for each group (within-group analysis; paired t-tests) for the DMN (A), CEN (B), and SN (C). ACC anterior cingulate cortex, aINS anterior insula, dlPFC dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, FUG fusiform gyrus, HC hippocampus, LinG lingual gyrus, mPFC medial prefrontal cortex, PrCG precentral gyrus, PrCu precuneus, pMTG posterior middle temporal gyrus, rPFC rostral prefrontal cortex, SMA supplementary motor area, Thal thalamus, TPOsup superior temporal gyrus (temporal pole). Seed regions are in cyan. Color scales indicate the t values.

Summary of functional connectivity. Pairs of brain regions showing greater functional connectivity in the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition. Only significant functional connectivity is displayed for each group. DMN (blue blobs), CEN (red blobs), and SN (green blobs), along with the connecting lines, represent the links between a seed region and its functionally connected regions. dlPFC dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (R: right), vPrCu ventral precuneus, rPFC rostral prefrontal cortex, pMTG posterior middle temporal gyrus, mPFC medial prefrontal cortex, dPrCu dorsal precuneus, HC hippocampus, aINS anterior insula, PrCG precentral gyrus.

As shown in Fig. 5, the Fast Group demonstrated a greater number of brain regions with increased functional connectivity in the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition, relative to the Slow Group. When comparing functional connectivity across the CEN, DMN, and SN, significant differences were observed between the CEN and DMN for the Fast Group in the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition (mean functional connectivity: 0.427) compared to the no-tACS condition (mean functional connectivity: 0.183; t(9) = 4.74, p = 0.001, Fig. 6A) and the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition (mean functional connectivity: 0.256; t(9) = 3.17, p = 0.011, Fig. 6C). Additionally, marginally significant differences were found between the Fast and Slow Groups in the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the no-tACS condition (t(9) = 1.86, p = 0.079, Fig. 6A) and the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition (t(9) = 2.06, p = 0.055, Fig. 6C). There were no significant differences between the Fast and Slow Groups in the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the no-tACS condition (Fig. 6B).

Phase-dependent tACS-mediated modulation in functional connectivity across the CEN, DMN, and SN. Mean changes in functional connectivity are indicated by the thickness of connecting lines, with values shown for both the Fast and Slow Groups. Panels represent functional connectivity differences for the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the no-tACS condition (A), the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the no-tACS condition (B), and the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition (C). Red lines indicate positive functional connectivity changes, while blue lines indicate negative changes. Statistically significant differences in functional connectivity within groups (paired t-tests; Fast and Slow Groups) and between groups (two-sample t-tests; Fast vs. Slow Groups) across the CEN, DMN, and SN are marked with an asterisk (p < 0.05).

Interestingly, as shown in Fig. 7, we found opposite patterns of tACS-phase-dependent relationships between performance accuracy and functional connectivity between DMN and SN during the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition relative to the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition for both the Fast and Slow Groups. Specifically, in the Fast Group, we observed a significant positive correlation, whereas in the Slow Group, we observed a significant negative correlation between task performance accuracy and the averaged functional connectivity measures between DMN and SN under the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition. The other network combinations of functional connectivity (i.e., CEN-DMN and CEN-SN) did not show statistically significant correlations with behavioral performance.

Opposite patterns of tACS-phase-dependent correlation between DMN-SN functional connectivity and task performance accuracy in Fast and Slow Groups. The scatter plot illustrates the correlation between task performance accuracy (%) and functional connectivity across the default mode network (DMN) and the salience network (SN) in the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition. In the Fast Group (red), higher DMN-SN functional connectivity is associated with greater task performance accuracy (r = 0.76, p = 0.01). Conversely, in the Slow Group (blue), higher DMN-SN functional connectivity is linked to lower task performance accuracy (r = − 0.67, p = 0.03), suggesting an opposite pattern of correlation across groups during the 45°-phase-lag tACS contrasted with the 180°-phase-lag tACS.

Discussion

We observed several neural correlates of fMRI data for the tACS-phase-dependent modulated behavioral performance during the working-memory task. In the Fast Group, the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition yielded a significant increase in reaction times (Fig. 3A), indicating the feasibility of anti-correlated-network-mediated intentional neuromodulation of working-memory performance. For the neural correlates of this behavioral change, the hippocampus in the right hemisphere exhibited significant activation in the Fast Group compared to the Slow Group during the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition (Fig. 3C, Fig. S3, and Table S2). This finding of spatially isolated and selective hippocampal activation may reflect phase-specific tACS-mediated neurophysiological correlates during the task performance since the hippocampus is one of the key nodes in working-memory function60. When the right hippocampus was assigned to a seed for the functional connectivity, the functional connectivity of the right anterior insular was increased in the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition. The observed right-lateralization during memory performance was consistent with previous studies. It has been reported that delay activity during working-memory performance was limited to the right insular61, and the right-hemispheric insular and hippocampus activation increased in patients with working-memory deficits62. In addition, as the high- but not the low-memory-load condition yielded activity lateralized to the right hemisphere63, our letter-digit combined 7-item workload in the working-memory task might induce right lateralization.

Notably, the anterior, not posterior, insular showed significant functional connectivity with the hippocampus. Consistently, the anterior insular was activated during the delayed matching experiment64, which is similar to the Sternberg task in the present study. It has also been reported that core DMN regions are anti-correlated with the dorsal anterior insular (dAI) and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC)65,66. Reportedly, the insula is a multimodal integration region providing an interface between external information and internal motivational states28,67. The dAI and dACC were found to be functionally connected to a set of regions described as a decision-making and cognitive control network68,69. Compared to the posterior insular, it has been suggested that the anti-correlation pattern between the DMN and CEN is modulated by an anterior insular(AI)-based network, which primarily comprises the AI and dACC30,70. For instance, the AI is involved in a wide range of cognitive processes, including switching between cognitive resources71 and reorienting attention72. Thus, the AI may have been consistently implicated in switching the dominant processing network between the CEN and DMN as one of the key nodes in the SN of this study.

In the right hemisphere, the fMRI signal of AI (an SN node) was positively synchronized with the pMTG signal. Previous fMRI working-memory studies consistently demonstrated that delayed vibrotactile frequency discrimination under distraction73 and a delayed match-to-sample task74 were correlated with activation in both MTG and AI, particularly in the right hemisphere. Indeed, individuals with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) exhibited negative resting-state functional connectivity between the right AI and the right MTG75. As such, the right-hemispheric fronto-parietal network is mainly involved in selective attention, so the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition might facilitate selective attention during a working-memory task. In addition, since activation of the right MTG has also been related to object-recognition in visual perception76, the letter-digit combined stimuli in the present study appeared to be efficiently processed with enhanced selective attention during the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition in the Fast Group.

Meanwhile, the pMTG and fusiform gyrus in the left hemisphere were activated when rPFC (a CEN node) in the same hemisphere was designated as a seed for the functional connectivity. It is likely that the pMTG in the left hemisphere was under the control of the CEN, while that in the right hemisphere was regulated by the SN. As the Sternberg task utilized in the present study predominantly required verbal (letters/numbers) working-memory demands that might rely on a greater proportion of left-hemisphere mediated resources77,78, the observations in left-hemisphere involved functional connectivity are interpretable in this context. Since rPFC is associated with the mentalizing category79 and the pMTG and fusiform gyrus have been associated with working-memory function80,81, the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition seemed to facilitate mentalizing processing during the present Sternberg task. Additionally, the lingual gyrus in both hemispheres was activated when the right rPFC was used as a seed, which is consistent with the previous studies reporting that the lingual gyrus is also involved in working-memory function81,82.

Regarding the precuneus, its dorsal part was activated when mPFC was a seed, whereas its ventral part was activated when dlPFC in the right hemisphere was a seed. In general, the precuneus is a functional core of the DMN83,84 and plays a critical role in working-memory performance85. In accordance with our observations, previous studies reported that the dorsal precuneus exhibited pronounced functional connectivity with the right frontoparietal network implicated in attention and working memory84,86. Additionally, a significant memory effect has been exhibited in the dorsal precuneus, predominantly in the right hemisphere87. On the other hand, the ventral precuneus has been known to be key for the mnemonic representational aspects necessary for an exemplar-based judgment process88,89. The ventral precuneus has been found to re-activate for stimuli that are familiar due to recent exposure90,91, and activity levels in the ventral precuneus predicted performance after learning89. The ventral precuneus could also be involved either in directing attention toward internal memory representations stored in the hippocampus-centered medial temporal lobe (MTL) or in the retrieval of memory representations used for decision-making92. Moreover, the CEN centered at the dlPFC is essential for the active maintenance and manipulation of information in working memory93,94,95,96,97,98,99. Thus, in the present study, the dlPFC (a CEN node) seemed to further communicate with the ventral precuneus (a DMN node) during the encoding-retrieval flip, reflected in prominent functional connectivity in the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition as compared to the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition. As the ventral precuneus is involved in building and retrieving memory representations with the hippocampus-centered MTL and the mPFC89,92, the DMN and CEN seem to be coordinated with the dorsal and ventral precuneus during working-memory performance. Furthermore, in the present study, the right hippocampus showed tACS-phase-specific modulation of functional connectivity with the anterior insular (an SN node) during working-memory performance (Fig. 4; Table 1).

Taken together, the significant right-lateralized functional connectivity in the dorsal and ventral precuneus observed in the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition in the Fast Group may indicate the tACS-phase-dependent modulation of the DMN in relation with the SN (for the dorsal precuneus) and CEN (for the ventral precuneus) during working-memory performance. Consistently, we observed a significant enhancement in functional connectivity between the CEN and DMN under the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the no-tACS (Fig. 6A) and 180°-phase-lag tACS conditions (Fig. 6C) in the Fast Group. Such a series of neurodynamics in functional connectivity across CEN, DMN, and SN (Fig. 5) might account for the tACS-mediated neuromodulation in task performance in the Fast Group. It is also noteworthy that we observed significant positive (in the Fast Group) and negative (in the Slow Group) correlations between task performance accuracy and the averaged functional connectivity measures between DMN and SN in the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition (Fig. 7). Specifically, during the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition relative to the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition, higher functional connectivity between DMN and SN was associated with greater task performance accuracy in the Fast Group, whereas in the Slow Group, higher DMN-SN functional connectivity was linked to lower task performance accuracy. This suggests that the behavioral effects of phase-lag tACS depend on an individual’s performance level and the functional neurodynamics between the DMN and SN.

As compared to these results of functional connectivity, we observed that the PCC was influenced by the manipulation of tACS phases but was not related to behavioral performance, since PCC was activated under the 180°-phase-lag tACS contrasted with the 45°-phase-lag tACS but irrespective of the type of group (noting that only the Fast Group exhibited tACS-mediated behavioral modulation; Fig. 3AB). As the PCC is one of the DMN nodes, PCC seems to be involved in the way to tACS-phase-dependent processes. Presumably, there would be disinhibition (or gating) in this early-processing DMN node for the downstream cascade processes, resulting in tACS-phase-dependent behavioral modulation in the Fast Group. This is because we observed the significantly prominent functional connectivity particularly in the Fast Group during the 45°-phase-lag tACS contrasted with the 180°-phase-lag tACS (Figs. 4 and 5), simultaneously with PCC activation during the 180°-phase-lag tACS contrasted with the 45°-phase-lag tACS (Fig. 3B, Fig. S3, and Table S2), which seems to be contradictory in terms of the fMRI results induced by different tACS phases. That is, under the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition, less suppressed (i.e., disinhibited) deactivation and the enhanced functional connectivity were simultaneously detected in the DMN region. To some extent, such contradictory neurodynamic behaviours within the DMN regions are characteristic of the DMN. For example, there is a reciprocal relationship between the DMN and the visual stream network along with the visual processing stream during conscious perception100. Thus, the present observations are probably due to the 180°-tACS-mediated active suppression of deactivation in the DMN region centered at PCC because this region showed prominent deactivation during the task performance without tACS treatment, noticeably disappearing in the Fast Group (Supplementary Fig. S2B). Consequently, the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition might actively interrupt the functional connectivity necessary for better task performance, exhibiting a relatively prominent connectivity in the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition compared to the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition of the Fast Group (Figs. 4 and 5), resulting in significantly increased reaction times (Fig. 3A).

As compared to such prominent functional connectivity during the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition of the Fast Group, the Slow Group exhibited a single connectivity with the right precentral gyrus being activated when the anterior insular of the same hemisphere was assigned to a functional connectivity seed (Fig. 5B). In both the right precentral gyrus and right insula, hypoactivation was observed during working-memory processing in patients with major depressive disorder101. Presumably, the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition could also modulate behavioral (attention and executive) characteristics of the Slow Group during working-memory performance.

It is also noteworthy that the present non-invasive electrical stimulation utilizing the anti-correlated relationship between CEN and DMN significantly activated the deep brain structure such as the hippocampus, known as an essential region of learning and memory102,103. That is, the hippocampus was activated (Fig. 3C) even though the tACS in this study was targeted principally to cortical regions as well as non-hippocampal subcortical structures such as mPFC and PCC. We had not intended to target the hippocampus at the beginning of this study, and it is difficult to do so under the technical limitations of current non-invasive neuromodulatory technology, but it was selectively and prominently activated depending on the task-relevant phases of tACS signals. Presumably, our stimulation influenced not only the targeted regions but also the entire corresponding network relevant to working-memory functions in which the hippocampus was involved. This tACS-mediated subsidiary non-target activation, even in subcortical structures if involved in task performance, is a newly observed non-invasive neuromodulatory technique to stimulate or effectively drive activation in task-relevant subcortical structures in a non-invasive manner. Thus, the selective activation of a task-relevant subcortical structure can be induced even by non-invasive scalp stimulation when manipulating appropriate stimulus parameters.

However, compared to a previous study demonstrating tACS-mediated cognitive improvement primarily in individuals with low verbal working memory ability51, our study observed inconsistent results, with tACS effects being particularly prominent in the Fast Group. This discrepancy may arise due to several key differences between the studies. First, the verbal N-back task used in the previous study51 and the Sternberg task employed in our study engage distinct cognitive processes. Although both assess working memory capacity, they rely on different cognitive components. The Sternberg task requires participants to retain a sequence of items in short-term memory and later determine whether a presented stimulus matches one of the previously seen items. This task primarily evaluates active maintenance and controlled retrieval abilities. In contrast, the N-back task presents stimuli sequentially, requiring participants to decide whether the current stimulus matches the one presented N trials earlier. While both tasks demand active maintenance and cognitive control, the N-back task does not necessarily require controlled retrieval. Due to these differences, the two tasks assess distinct aspects of working memory, and performance in each may be influenced by different cognitive mechanisms. Second, response time, which was used to classify participants into either the Fast or Slow Group in our study, does not necessarily correlate with performance scores on the N-back task, which was used to categorize participants into low- and high-performance groups in the previous study51. For example, longer reaction times can sometimes be associated with improved performance accuracy, resulting in higher N-back task scores. Nevertheless, given the importance of non-invasive neuromodulatory effects for both low and high performers, the observed inconsistencies in tACS effects across different performance levels should be systematically investigated in future studies.

Our present observations provide several inspiring points for future potent neuromodulatory technology. First, the present modulation of working-memory performance can be understood in terms of plausible underlying neurophysiological mechanisms of the PFC-hippocampal involvement in the framework of anti-correlated neurodynamics between CEN and DMN. Second, as compared to most of the previous two-region-based stimulation studies utilizing a functionally anti-correlated relationship104,105,106,107,108,109, our present study firstly introduced a network-wise approach using an MR-compatible multiple-channel high-definition transcranial electrical stimulator system on the functionally anti-correlated networks, CEN and DMN (Fig. 2C and Supplementary Fig. S6). Third, our findings directly support that some of the variability of non-invasive brain stimulation effects may be associated with the specific phase-dependent temporal relation across corresponding task-relevant brain regions, suggesting that this information could be considered when designing a neuromodulatory paradigm, leading to more efficient stimulation protocols in the context of mutually anti-correlated networks of CEN and DMN. Fourth, the transcranial brain stimulation using an optimal phase lag between CEN and DMN could selectively target a task-relevant deep brain structure (e.g., the hippocampus in a memory task). Presumably, this could be achieved by means of stimulation propagation through the corresponding functional network from the scalp to the deep brain structure110. Moreover, an animal study showed that a new non-invasive brain stimulation protocol, termed temporal interference (TI), allows the entrainment of oscillatory neuronal activity in subcortical structures (such as the hippocampus) without recruiting neurons of the overlying cortex111. The TI technique has currently been highlighted as a potent tool for selectively stimulating a deep brain structure112, in which two different pairs of stimulation electrode sets are employed and the tACS frequency difference of the stimulation signals between these two electrode pairs is expected to be delivered to the targeted deep brain structure111. However, as shown in our findings (Fig. 3BC and Fig. S3), the deep brain structure can be selectively stimulated simply by using transcranial electrical stimulation with a phase lag. Thus, although more experimental validation is prerequisite, our observations provide a feasibility of additional non-invasive cognitive augmentation technology implementing non-invasive brain stimulations for cascade neurophysiological deep-brain activation. Further refined phase lags between CEN and DMN could be studied in future, and this approach can be adapted to various cognitive functions, which might slightly or profoundly differ in terms of their anti-correlated relationship between CEN and DMN.

Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. First, although a larger sample size would have improved the statistical power of our study, the sample sizes were limited due to the Fast and Slow subgrouping. Additionally, the inclusion of multiple inconvenient tACS conditions (i.e., the 45°-phase-lag tACS and the 180°-phase-lag tACS conditions) restricted further participant recruitment. As such, the statistical power should be carefully considered when interpreting the current findings. Second, we observed behavioral performance-dependent tACS effects in the present study. Specifically, for the Fast Group, anti-phase (i.e., 180°-phase-lag) tACS exhibited inhibitory effects, while partially in-phase (i.e., 45°-phase-lag) tACS showed no behavioral effects but did induce greater functional connectivity changes. It is presumed that the current anti-phase tACS further suppressed the activation of working-memory networks in participants who demonstrated fast performance. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that changes in functional connectivity do not necessarily lead to behavioral changes, as the two are not mutually dependent. Although a manifest and consistent relationship between tACS-mediated neural modulations and consequent behavioral changes aids in understanding robust brain-behavior correlations, the tACS-induced neural effects had no detectable behavioral consequences in some conditions. However, the clear differences in tACS effects between the Fast and Slow Groups underscore the critical importance of inter-individual variability in response to tACS.

Methods

Participants

Twenty-six healthy volunteers (nine females; mean age 24.1 ± 2.9 y) participated in this study. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. None reported a personal history of psychiatric or neurological disorders. All participants were free of neurological and psychiatric illnesses, any contraindications for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning, current and past alcohol/drug abuse or dependence, and current use of illicit substances. All participants provided written informed consent. The study, including the experimental protocols, was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines established and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Korea University (No. KUIRB-2021-0209-06).

Sternberg memory task

We used the Sternberg task to investigate the neuromodulatory effect of phase-lagged CFC-tACS treatment on working-memory performance55. The Sternberg task, a classical test of working memory, is well suited for investigating brain activity related to working-memory load because each trial has a well-defined retention period over which participants should hold the information of items presented in the encoding phase.

As a small memory-set size in the Sternberg task may lead to difficulty in revealing the tACS effect, we selected a 7-item memory span and modified a presented item (commonly either a digit or a letter) into a complex one (a letter-digit combined format; Fig. 2B). Thus, the presented items in the Sternberg task were a combination of one letter and one digit randomly drawn from a series of single letters (A–Z) and digits (0–9). When generating sets of letter-digit stimuli for each trial, the letters and digits were randomly drawn without replacement. For example, seven letter-numeral combinations (e.g., Y2, X0, I5, J3, D4, A9, C7) were visually presented consecutively (one at a time) on the display monitor for 700 ms with an ISI of 150 ms (Fig. 2B). The items were presented randomly and equally often to each participant. The black-colored letter-digit combined items subtended 7.0° of visual angle and were presented on a gray background. Following the 7-item encoding phase, the retention phase lasted 9 s, and the onset of a test probe (test stimulus) marked the beginning of the retrieval phase. Participants then had to respond as fast as possible by pressing a button with their right or left thumb, indicating whether the probe item was or was not part of the memory set presented during the encoding phase. The probe had an equal probability of being part of the memory set or not. Response hands were counterbalanced across participants. The probe was presented for 2 s. Following participants’ response, visual feedback (“Correct!”, “Incorrect!”, or “No Response”) was promptly shown for 1 s to motivate participants to improve performance. The inter-trial interval was 6 s, which began with the visual feedback offset and ended with the onset of the next trial. Stimuli were presented using E-prime stimulus presentation software (E-prime 3.0 Professional, Psychology Software Tools, Sharpsburg, USA). The reaction times and performance accuracies were compared using false discovery rate (FDR)-corrected two-sided paired t-tests113.

Cross-frequency tACS neuromodulation

Among the tACS phase-lag (\(\:{\Delta\:}\phi\:\)) values that could potentially facilitate or suppress task performance, we determined 45 degrees and 180 degrees, respectively, as the optimal lags for partially in-phase and out-of-phase conditions in the present study. This choice was based on previous studies empirically reporting the mPFC (a DMN node) leading the PPC (a CEN node) with a phase-lag range of 24° ± 15° for optimal behavioral performance, and 180° (full anti-phase) for worst behavioral performance during a decision-making task38,114. Compared to the two-site tACS stimulation of the previous studies, however, our present study deployed a network-wise tACS approach using the anti-correlated relationship between subnetworks CEN and DMN.

TACS was delivered online for the entire 9-s retention period of every trial of the Sternberg task performances using an MR-compatible 64 M×N high-definition (HD) transcranial electrical stimulator system (Soterix Medical Inc., New York, USA) with intensities below their individual sensation threshold using the individual task-relevant frequency (within the theta and alpha bands) of the CFC-tACS, subsequently ranging from 0.6 to 1.5 mA peak-to-baseline.

The right/left PPC and right/left dlPFC were stimulation targets for the CEN, and the mPFC and PCC for the DMN. For spatially accurate stimulation, subject-specific optimized coordinates of stimulation target regions were computed based on individual T1 images. An example montage for a single individual is shown in Fig. 8. Generally, center-surround antagonistic configuration was used for the coordination of the stimulation and return channels, respectively (that is, return electrodes were arranged in a ring around the central stimulation electrode). The currents of all stimulation and return channels were set to keep the total amount of current at a zero sum.

tACS channel montage for a single participant. Red indicates the stimulation channels, and blue indicates the surrounding return channels. Each green ring indicates a modular subset of stimulation and return channels for each target region, dlPFC dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, PPC posterior parietal cortex, mPFC medial prefrontal cortex, PCC posterior cingulate cortex. Montages for all individuals are shown in Supplementary Fig. S7.

The tAC stimulus wave was designed as a cross-frequency coupled pattern. The lower frequency was selected based on the subject-specific peak in the theta-alpha band range (4–13 Hz) and the high frequency as the peak in the high-gamma range 50–250 Hz (Fig. 2C). To establish the theta-alpha-phase and high-gamma-amplitude coupled pattern, we used the following equations coded in MATLAB (ver. R2021a, MathWorks Inc., Natick, USA):

where \(\:{f}_{P}\) and \(\:{f}_{A}\) are theta-alpha and gamma frequency, respectively. \(\:{\overline{A}}_{{f}_{P}}\) and \(\:{\overline{A}}_{{f}_{A}}\)are constants that determine the maximum amplitude of \(\:{f}_{P}\) and \(\:{f}_{A}\), respectively. N is the number of return channels. CFC-tACS stimulus was generated with a sampling frequency of 1000 Hz. \(\:{\overline{A}}_{{f}_{P}}\) and \(\:{\overline{A}}_{{f}_{A}}\) were set to 0.8 and 0.2, respectively.

The theta or alpha frequency (\(\:{f}_{P}\)) for the generation of the stimulus was individually selected as the dominant activity within theta and alpha bands based on the fast Fourier transformed results on individual EEG data during the retention period of task performance before stimulation and before the main fMRI experiment. It has been proposed that the number of gamma cycles per lower-frequency cycle determines the working-memory capacity of the buffer23 based on the CFC-memory model21,24. The gamma frequency (\(\:{f}_{A}\)) for the CFC-tACS stimulation was individually selected based on individual CFC results using the EEG session, in which EEG signals of the retention period were recorded during the Sternberg task without tACS. We confined the high-gamma range to 50–250 Hz. In the present study, we used a peak-coupled CFC-tACS to investigate whether a peak-coupled theta-alpha-phase/high-gamma-amplitude CFC-tACS treatment perturbed the degree of ongoing CFC, possibly associated with significant changes in working-memory performance. To use the individually customized CFC waveforms in tAC stimulation protocols, the generated CFC-formed tAC stimulus file was loaded into a 64 M×N HD stimulator system. The stimulation duration was 9 s with a 200-ms ramp-up and ramp-down for each stimulus. Using an oscilloscope, we double-checked whether the CFC-formed signals physically generated the exact amplitude, shape, and frequency that were intended during the design phase.

Using a simulation program (tES LAB software, ver. 3.0, Neurophet, Korea), we examined whether the stimulation signals matched the intended phase lag (either 45° or 180°) before the main study. The averaged electric field intensity (V/m) was 0.12 V/m at the activated cortical region. As shown in Fig. 2C and Supplementary Fig. S6, the simulation results demonstrated that the activation regions were considerably well aligned with the intended target regions. For example, as shown in Fig. 8, the stimulation electrode Cz was selected to target the PCC (a DMN node) as it provided the most optimized stimulation of the PCC based on the simulation results. Moreover, whether the phase difference between the CEN and DMN stimulation signals exactly matched the intended phase lag (either 45° or 180°) was investigated (Supplementary Fig. S6B).

Experimental design

Each participant performed 30 trials for the 45°-phase-lag tACS and 30 trials for the 180°-phase-lag tACS. The Sternberg task was repeatedly applied to the same participant during and after either the 45°-phase-lag or 180°-phase-lag tACS to investigate both the ongoing and after-treatment effects of phase-lag-modulated tACS treatment on working-memory performance. Thus, the task flow was as follows: (1) fMRI-session performing the task without tACS, (2) tACS-fMRI session performing the task with a 45° phase-lag CFC-tACS, (3) fMRI-session performing the task without tACS, (4) tACS-fMRI session performing the task with a 180° phase-lag CFC-tACS, and (5) fMRI-session performing the task without tACS (Fig. 2A). The order of 45° and 180° phase-lag CFC-tACS sessions was counterbalanced across participants.

Since prior research has suggested that the efficacy of tACS may vary based on the initial task performance level56,57,58,59, with low performers more likely to benefit from tAC stimulation than high performers, we divided participants into two groups based on the median split of their individual mean reaction times during the first fMRI run without tAC stimulation. We labelled these groups Slow Group and Fast Group. After subgrouping and excluding 6 participants due to excessive head motion, the Fast and Slow groups each consist of 10 participants.

fMRI acquisition

Whole-brain images were collected with a Siemens 3T MAGNETOM Trio Tim syngo scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) and a 32-channel head coil. Before the experiment, participants received a detailed explanation of the experimental procedure and were familiarized with the experimental surroundings and stimuli. Participants were instructed to keep their eyes open and gaze at the MR-compatible screen located at the end of the MRI bed through the mirror positioned on the head coil. The distance between the screen and the participants was approximately 245 cm, and the diameter of the stimulus on the screen was 30 cm, resulting in a visual angle of 7.0°. To maximize participants’ concentration on the task, darkness was maintained both inside and outside the MRI shielding room during the experiment. After acquiring automated scout images and performing shimming procedures to optimize field homogeneity, 360 blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) fMRI image volumes were collected using an interleaved T2*-weighted echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence for each fMRI session. A total of 75 slices per volume were obtained with the following parameters: repetition time (TR) = 2000 ms; echo time (TE) = 30 ms; flip angle (FA) = 90°; multi-band acceleration factor = 3; acquisition matrix = 96 × 96; field of view (FOV) = 192 × 192 mm2; in-plane voxel size = 2 × 2 × 2 mm3; no slice gap. High-resolution structural scans of 3-dimensional anatomical magnetisation prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) images were collected for each subject after fMRI data collection (TR = 2.3 s; TE = 2.13 ms; inversion time (TI) = 0.9 s; FA = 9°; acquisition matrix = 256 × 256; in-plane voxel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm3; 224 sagittal slices).

fMRI data analysis

BOLD images were processed and analyzed using Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM12; https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12) in MATLAB (ver. R2021a, Mathworks Inc., Natick, USA). Functional images were pre-processed with a standard task-based fMRI processing pipeline: slice-timing correction (using the first slice as the reference slice), motion correction, co-registration, gray/white matter segmentation, normalization to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template, and spatial smoothing using a 6-mm full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) Gaussian kernel. A temporal high-pass filter with a 128-second cutoff was applied to remove low-frequency signal drift, and serial correlations from aliased biorhythms in the time series were adjusted for using an autoregressive AR 1 model. The movement parameters from the realignment procedure (x, y, z, roll, pitch, and yaw) were used as regressors of non-interest in the first-level analysis. The data of six participants were excluded from further analyses due to their excessive head motion (i.e., translational displacement greater than 3 mm and rotational displacement more than 3°) during the fMRI session.

Statistical analysis of fMRI maps relied on random-effects modelling. For the first-level analysis, we analyzed whole-brain activity during the retention period of the Sternberg task relative to a rest block for each fMRI session—that is, for each participant, we generated a contrast image of retention > rest. To investigate the effect of phase-lag-modulated tACS treatment on working-memory performance, the generated contrast images (retention > rest) from the first-level analyses for each fMRI session were submitted to a second-level analysis across subjects, which employed a general linear model with random effects. Using one-sample t-tests, we detected statistically significant whole-brain activity within each stimulation condition (no-tACS, 45°-phase-lag CFC-tACS, and 180°-phase-lag CFC-tACS). In addition, paired t-tests were employed to detect significant differences in brain activation across the three stimulation conditions (no-tACS vs. 45°-phase-lag CFC-tACS; no-tACS vs. 180°-phase-lag CFC-tACS; 45°-phase-lag CFC-tACS vs. 180°-phase-lag CFC-tACS). The random-effects analysis was conducted separately for the Fast Group, Slow Group, and Both Groups, each time separately testing for increased activation (retention > rest) and decreased activation (retention < rest). This enabled us to investigate whether working-memory function under tACS neuromodulation was associated with patterns of brain excitation or suppression (see Supplementary Fig. S2 and Table S1 for increased/decreased activation maps of the three groups). To correct for multiple comparisons, we set a voxel-level threshold of p < 0.001 and a cluster-level family-wise error (FWE) of p < 0.05. In addition, we performed the region of interest (ROI) analyses for the representative nodes of CEN, DMN, and SN are as follows: dlPFC and PPC for CEN; mPFC, PCC, and hippocampus for DMN; and ACC, anterior insula, rPFC, and supramarginal gyrus for SN. The results were shown in Fig. S4 and Table S3.

To study group-tACS interactions, a full factorial design was conducted to detect activated voxels associated with the three tACS conditions (Stimulation factor: no tACS, 45°-phase-lag CFC-tACS, and 180°-phase-lag CFC-tACS) across the two groups (Group factor: Fast and Slow). To correct for multiple comparisons, a voxel-level threshold of p < 0.001 was set, and a cluster-level FWE of p < 0.05 was used.

Task-related functional connectivity

To investigate the tACS phase-lag-mediated differences in functional connectivity between the Fast and Slow Groups during the Sternberg task, we conducted seed-based functional connectivity in both 45°-phase-lag tACS and 180°-phase-lag tACS using the Functional Connectivity toolbox, a MATLAB-based cross-platform software (https://www.nitrc.org/projects/conn/, Whitfield-Gabrieli and Nieto-Castanon115). Based on previous studies116,117,118, we defined the following brain regions as seed regions: dlPFC and PPC for CEN; mPFC, PCC, and hippocampus for DMN; and ACC, anterior insula, rPFC, and supramarginal gyrus for SN, according to the CONN’s HCP-ICA networks and the automated anatomical atlas (AAL)119.

For the functional connectivity analysis, the fMRI time series of all voxels within the gray matter were pre-processed by regressing out six rigid motions, noise components of the white matter and the cerebrospinal fluid masks, linear trends, and cosine and sine waveforms up to 0.009 Hz. After regression, functional connectivity was calculated using the correlation coefficients between the seed time series and those of the whole brain voxels in the task condition. The correlation coefficients were Fisher z-transformed. To assess the statistical significance of the seed-based functional connectivity within each group, we conducted one-sample t-tests for each group (i.e., Fast and Slow Groups) and cluster size threshold estimation. For the tACS phase differences of the seed-based functional connectivity at the second-level analyses, paired t-tests were conducted with the voxel-level significance threshold at p < 0.001. This was followed by cluster size analysis using a cluster-level FWE of p < 0.05 to correct for multiple comparisons. To analyze functional connectivity changes across the three networks (CEN, DMN, and SN), we calculated the Fisher z-transformed correlation coefficients between pairs of time series from the three networks. Within-group analysis was conducted using paired t-tests, while between-group analysis (i.e., Fast vs. Slow Groups) was performed using two-sample t-tests. In addition, to examine brain-behavior correlations, Pearson correlations were computed between behavioral data (either task performance accuracy or reaction times) and the averaged functional connectivity measures across pairs of the CEN, DMN, and SN during the 45°-phase-lag tACS condition relative to the 180°-phase-lag tACS condition for both the Fast and Slow Groups.

Data availability

The data and analysis codes used in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

13 December 2024

The original online version of this Article was revised: The Funding section in the original version of this Article was omitted. The Funding section now reads: “This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (grant number RS-2025-00513128 to B.-K.M.), the KBRI basic research program through Korea Brain Research Institute funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (grant number 25-BR-03-01 and 25-BR-03-02 to D.L.), and the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (grant number RS-2024-00401794 to D.L.).”

References

Engle, R. W., Kane, M. J. & Tuholski, S. W. Individual differences in working memory capacity and what they tell us about controlled attention, general fluid intelligence, and functions of the prefrontal cortex. (1999).

Hanslmayr, S., Axmacher, N. & Inman, C. S. Modulating human memory via entrainment of brain oscillations. Trends Neurosci. 42, 485–499 (2019).

Murphy, O. et al., Transcranial random noise stimulation is more effective than transcranial direct current stimulation for enhancing working memory in healthy individuals: Behavioural and electrophysiological evidence. Brain Stimul. (2020).

Röhner, F. et al. Modulation of working memory using transcranial electrical stimulation: a direct comparison between TACS and TDCS. Front. NeuroSci. 12, 761 (2018).

Reinhart, R. M. G. & Nguyen, J. A. Working memory revived in older adults by synchronizing rhythmic brain circuits. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 820–827 (2019).

Rozisky, J. R., Antunes, L. C., Brietzke, A. P., de Sousa, A. C. & Caumo, W. Transcranial direct current stimulation and neuroplasticity. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS): Emerging Used, Safety and Neurobiological Effects. L Rogers (eds). Nova Science Publishers Inc., 1–26. (2016).

Yamada, Y. & Sumiyoshi, T. Neurobiological mechanisms of transcranial direct current stimulation for psychiatric disorders; neurophysiological, chemical, and anatomical considerations. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 15, 631838 (2021).

Wischnewski, M., Alekseichuk, I. & Opitz, A. Neurocognitive, physiological, and biophysical effects of transcranial alternating current stimulation. Trends Cogn. Sci. (2022).

Tran, H., Shirinpour, S. & Opitz, A. Effects of transcranial alternating current stimulation on spiking activity in computational models of single neocortical neurons. Neuroimage 250, 118953 (2022).

Jausovec, N. & Jausovec, K. Increasing working memory capacity with theta transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS). Biol. Psychol. 96, 42–47 (2014).

Vosskuhl, J., Huster, R. J. & Herrmann, C. S. Increase in short-term memory capacity induced by down-regulating individual theta frequency via transcranial alternating current stimulation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9 (2015).

Santarnecchi, E. et al. Frequency-Dependent enhancement of fluid intelligence induced by transcranial oscillatory potentials. Curr. Biol. 23, 1449–1453 (2013).

Herrmann, C. S., Rach, S., Neuling, T. & Strüber, D. Transcranial alternating current stimulation: a review of the underlying mechanisms and modulation of cognitive processes. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7, 279 (2013).

Ali, M. M., Sellers, K. K. & Fröhlich, F. Transcranial alternating current stimulation modulates large-scale cortical network activity by network resonance. J. Neurosci. 33, 11262–11275 (2013).

Helfrich, R. F. et al. Entrainment of brain oscillations by transcranial alternating current stimulation. Curr. Biol. 24, 333–339 (2014).

Zaehle, T., Rach, S. & Herrmann, C. S. Transcranial alternating current stimulation enhances individual alpha activity in human EEG. PloS One. 5, e13766 (2010).

Weinrich, C. A. et al. Modulation of long-range connectivity patterns via frequency-specific stimulation of human cortex. Curr. Biol. 27, 3061–3068 (2017).

Tavakoli, A. V. & Yun, K. Transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) mechanisms and protocols. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 11, 214 (2017).

Riddle, J., McFerren, A. & Frohlich, F. Causal role of cross-frequency coupling in distinct components of cognitive control. Prog. Neurobiol. 202, 102033 (2021).

Jensen, O. & Colgin, L. L. Cross-frequency coupling between neuronal oscillations. Trends Cogn. Sci. 11, 267–269 (2007).

Lisman, J. E. & Idiart, M. A. Storage of 7+/-2 short-term memories in oscillatory subcycles. Science 267, 1512–1515 (1995).

Canolty, R. T. et al. High gamma power is phase-locked to theta oscillations in human neocortex. Science 313, 1626–1628 (2006).

Jensen, O. Maintenance of multiple working memory items by Temporal segmentation. Neuroscience 139, 237–249 (2006).

Ward, L. M. Synchronous neural oscillations and cognitive processes. Trends Cogn. Sci. 7, 553–559 (2003).

Greicius, M. D., Krasnow, B., Reiss, A. L. & Menon, V. Functional connectivity in the resting brain: a network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100, 253–258 (2003).

Fox, M. D., Corbetta, M., Snyder, A. Z., Vincent, J. L. & Raichle, M. E. Spontaneous neuronal activity distinguishes human dorsal and ventral attention systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 103, 10046–10051 (2006).

Golland, Y. et al. Extrinsic and intrinsic systems in the posterior cortex of the human brain revealed during natural sensory stimulation. Cereb. Cortex. 17, 766–777 (2007).

Seeley, W. W. et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J. Neurosci. 27, 2349–2356 (2007).

Menon, V. Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: a unifying triple network model. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15, 483–506 (2011).

Sridharan, D., Levitin, D. J. & Menon, V. A critical role for the right fronto-insular cortex in switching between central-executive and default-mode networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 12569–12574 (2008).

Raichle, M. E. et al., A default mode of brain function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98, 676–682 (2001).

Menon, V. & Uddin, L. Q. Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of Insula function. Brain Struct. Funct. 214, 655–667 (2010).

Peters, S. K., Dunlop, K. & Downar, J. Cortico-striatal-thalamic loop circuits of the salience network: a central pathway in psychiatric disease and treatment. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 10, 104 (2016).

Nekovarova, T., Fajnerova, I., Horacek, J. & Spaniel, F. Bridging disparate symptoms of schizophrenia: a triple network dysfunction theory. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 8, 171 (2014).

Bächinger, M. et al. Concurrent tACS-fMRI reveals causal influence of power synchronized neural activity on resting state fMRI connectivity. J. Neurosci. 37, 4766–4777 (2017).

Violante, I. R. et al., Externally induced frontoparietal synchronization modulates network dynamics and enhances working memory performance. Elife. 6 (2017).

Polanía, R., Nitsche, M. A., Korman, C., Batsikadze, G. & Paulus, W. The importance of timing in segregated theta phase-coupling for cognitive performance. Curr. Biol. 22, 1314–1318 (2012).

Polanía, R., Moisa, M., Opitz, A., Grueschow, M. & Ruff, C. C. The precision of value-based choices depends causally on fronto-parietal phase coupling. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–10 (2015).

Gevins, A., Smith, M. E., McEvoy, L. & Yu, D. High-resolution EEG mapping of cortical activation related to working memory: effects of task difficulty, type of processing, and practice. Cereb. Cortex. 7, 374–385 (1997).

Jensen, O. & Tesche, C. D. Frontal theta activity in humans increases with memory load in a working memory task. Eur. J. Neurosci. 15, 1395–1399 (2002).

Onton, J., Delorme, A. & Makeig, S. Frontal midline EEG dynamics during working memory. Neuroimage 27, 341–356 (2005).

Sarnthein, J., Petsche, H., Rappelsberger, P., Shaw, G. & Von Stein, A. Synchronization between prefrontal and posterior association cortex during human working memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95, 7092–7096 (1998).

Pahor, A. & Jaušovec, N. Multifaceted pattern of neural efficiency in working memory capacity. Intelligence 65, 23–34 (2017).

Hanslmayr, S. et al. Prestimulus oscillations predict visual perception performance between and within subjects. Neuroimage 37, 1465–1473 (2007).

Mathewson, K. E., Gratton, G., Fabiani, M., Beck, D. M. & Ro, T. To see or not to see: prestimulus α phase predicts visual awareness. J. Neurosci. 29, 2725–2732 (2009).

Klimesch, W. Memory processes, brain oscillations and EEG synchronization. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 24, 61–100 (1996).

Alekseichuk, I., Turi, Z., de Lara, G. A., Antal, A. & Paulus, W. Spatial working memory in humans depends on theta and high gamma synchronization in the prefrontal cortex. Curr. Biol. 26, 1513–1521 (2016).

de Lara, G. A. et al. Perturbation of theta-gamma coupling at the Temporal lobe hinders verbal declarative memory. Brain Stimul. 11, 509–517 (2018).

Turi, Z. et al., θ-γ Cross-Frequency Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation over the Trough Impairs Cognitive Control. eneuro. 7. (2020).

Akkad, H. et al., Increasing motor skill acquisition by driving theta-gamma coupling. BioRxiv. (2019).

Zeng, L., Guo, M., Wu, R., Luo, Y. & Wei, P. The effects of electroencephalogram feature-based transcranial alternating current stimulation on working memory and electrophysiology. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 828377 (2022).

Tseng, P. et al. Unleashing potential: transcranial direct current stimulation over the right posterior parietal cortex improves change detection in low-performing individuals. J. Neurosci. 32, 10554–10561 (2012).

Sahu, P. P. & Tseng, P. Frontoparietal theta tACS nonselectively enhances encoding, maintenance, and retrieval stages in visuospatial working memory. Neurosci. Res. 172, 41–50 (2021).

Tseng, P., Iu, K. C. & Juan, C. H. The critical role of phase difference in theta Oscillation between bilateral parietal cortices for visuospatial working memory. Sci. Rep. 8, 349 (2018).

Sternberg, S. High-speed scanning in human memory. Science 153, 652–654 (1966).

Daffner, K. R. et al. Mechanisms underlying age-and performance-related differences in working memory. J. Cognit. Neurosci. 23, 1298–1314 (2011).

Hsu, T. Y., Juan, C. H. & Tseng, P. Individual differences and state-dependent responses in transcranial direct current stimulation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 10, 643 (2016).

Jaeggi, S. M. et al. On how high performers keep cool brains in situations of cognitive overload. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 7, 75–89 (2007).

Dong, S., Reder, L. M., Yao, Y., Liu, Y. & Chen, F. Individual differences in working memory capacity are reflected in different ERP and EEG patterns to task difficulty. Brain Res. 1616, 146–156 (2015).

Baddeley, A., Jarrold, C. & Vargha-Khadem, F. Working memory and the hippocampus. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23, 3855–3861 (2011).

Pollmann, S. Yves von Cramon, D. Object working memory and visuospatial processing: functional neuroanatomy analyzed by event-related fMRI. Exp. Brain Res. 133, 12–22 (2000).

White, T., Hongwanishkul, D. & Schmidt, M. Increased anterior cingulate and Temporal lobe activity during visuospatial working memory in children and adolescents with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 125, 118–128 (2011).

Rypma, B. & D’Esposito, M. The roles of prefrontal brain regions in components of working memory: effects of memory load and individual differences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96, 6558–6563 (1999).

Courtney, S. M., Ungerleider, L. G., Keil, K. & Haxby, J. V. Transient and sustained activity in a distributed neural system for human working memory. Nature 386, 608–611 (1997).

Fox, M. D. et al. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102, 9673–9678 (2005).

Chang, C. & Glover, G. H. Effects of model-based physiological noise correction on default mode network anti-correlations and correlations. Neuroimage 47, 1448–1459 (2009).

Craig, A. D. How do you feel—now? The anterior Insula and human awareness. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 59–70 (2009).

Dosenbach, N. U. et al., Distinct brain networks for adaptive and stable task control in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 104, 11073–11078 (2007).

Grinband, J., Hirsch, J. & Ferrera, V. P. A neural representation of categorization uncertainty in the human brain. Neuron 49, 757–763 (2006).

Chand, G. B. & Dhamala, M. Interactions among the brain default-mode, salience, and central-executive networks during perceptual decision-making of moving Dots. Brain Connect. 6, 249–254 (2016).

Uddin, L. Q. & Menon, V. The anterior Insula in autism: under-connected and under-examined. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.. 33, 1198–1203 (2009).

Ullsperger, M., Harsay, H. A., Wessel, J. R. & Ridderinkhof, K. R. Conscious perception of errors and its relation to the anterior Insula. Brain Struct. Function. 214, 629–643 (2010).

Sörös, P. et al. Functional MRI of working memory and selective attention in vibrotactile frequency discrimination. BMC Neurosci. 8, 1–10 (2007).

Rahm, B., Kaiser, J., Unterrainer, J. M., Simon, J. & Bledowski, C. fMRI characterization of visual working memory recognition. NeuroImage 90, 413–422 (2014).

Zhao, Q. et al. Abnormal resting-state functional connectivity of insular subregions and disrupted correlation with working memory in adults with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Front. Psychiatry. 8, 200 (2017).

Langner, R., Eickhoff, S. B. & Bilalić, M. A network view on brain regions involved in experts’ object and pattern recognition: implications for the neural mechanisms of skilled visual perception. Brain Cogn. 131, 74–86 (2019).

Jennings, J. R., van der Veen, F. M. & Meltzer, C. C. Verbal and Spatial working memory in older individuals: A positron emission tomography study. Brain Res. 1092, 177–189 (2006).

Smith, E. E. & Jonides, J. Neuroimaging analyses of human working memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95, 12061–12068 (1998).

Gilbert, S. J. et al. Functional specialization within rostral prefrontal cortex (area 10): a meta-analysis. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 18, 932–948 (2006).

Chechko, N. et al. Effects of overnight fasting on working memory-related brain network: an fMRI study. Hum. Brain. Mapp. 36, 839–851 (2015).

Bergstrom, F. & Eriksson, J. Neural evidence for Non-conscious working memory. Cereb. Cortex. 28, 3217–3228 (2018).

Ragland, J. D. et al. Working memory for complex figures: an fMRI comparison of letter and fractal n-back tasks. Neuropsychology 16, 370 (2002).

Fransson, P. & Marrelec, G. The precuneus/posterior cingulate cortex plays a pivotal role in the default mode network: evidence from a partial correlation network analysis. Neuroimage 42, 1178–1184 (2008).

Utevsky, A. V., Smith, D. V. & Huettel, S. A. Precuneus is a functional core of the default-mode network. J. Neurosci. 34, 932–940 (2014).

Luber, B. et al. Facilitation of performance in a working memory task with rTMS stimulation of the precuneus: frequency-and time-dependent effects. Brain Res. 1128, 120–129 (2007).

Leech, R., Kamourieh, S., Beckmann, C. F. & Sharp, D. J. Fractionating the default mode network: distinct contributions of the ventral and dorsal posterior cingulate cortex to cognitive control. J. Neurosci. 31, 3217–3224 (2011).

Schott, B. H. et al. Gradual acquisition of visuospatial associative memory representations via the dorsal precuneus. Hum. Brain. Mapp. 40, 1554–1570 (2019).

Wirebring, L. K., Stillesjö, S., Eriksson, J., Juslin, P. & Nyberg, L. A similarity-based process for human judgment in the parietal cortex. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 12, 481 (2018).

Stillesjö, S., Nyberg, L. & Wirebring, L. K. Building memory representations for exemplar-based judgment: A role for ventral precuneus. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 13, 228 (2019).

Gilmore, A. W., Nelson, S. M. & McDermott, K. B. A parietal memory network revealed by multiple MRI methods. Trends Cogn. Sci. 19, 534–543 (2015).

Huijbers, W. et al. The encoding/retrieval flip: interactions between memory performance and memory stage and relationship to intrinsic cortical networks. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 25, 1163–1179 (2013).

Wagner, A. D., Shannon, B. J., Kahn, I. & Buckner, R. L. Parietal lobe contributions to episodic memory retrieval. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9, 445–453 (2005).

Bunge, S. A., Ochsner, K. N., Desmond, J. E., Glover, G. H. & Gabrieli, J. D. Prefrontal regions involved in keeping information in and out of Mind. Brain 124, 2074–2086 (2001).

Crottaz-Herbette, S., Anagnoson, R. & Menon, V. Modality effects in verbal working memory: differential prefrontal and parietal responses to auditory and visual stimuli. Neuroimage 21, 340–351 (2004).

Petrides, M. Lateral prefrontal cortex: architectonic and functional organization. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 360, 781–795 (2005).