Abstract

The assessment of apple quality is pivotal in agricultural production management, and apple ripeness is a key determinant of apple quality. This paper proposes an approach for assessing apple ripeness from both structured and unstructured observation data, i.e., text and images. For structured text data, support vector regression (SVR) models optimized using the Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA), Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO), and Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA) were utilized to predict apple ripeness, with the WOA-optimized SVR demonstrating exceptional generalization capabilities. For unstructured image data, an Enhanced-YOLOv8+, a modified YOLOv8 architecture integrating Detect Efficient Head (DEH) and Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) mechanism, was employed for precise apple localization and ripeness identification. The synergistic application of these methods resulted in a significant improvement in prediction accuracy. These approaches provide a robust framework for apple quality assessment and deepen the understanding of the relationship between apple maturity and observed indicators, facilitating more informed decision-making in postharvest management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Apples are among the most widely consumed fruits in the world, and assessing their quality is a crucial part of agricultural production management. In recent years, numerous studies have explored methods for assessing apple quality using various indicators that includes size, weight, shape, color, ripeness, sweetness, crispness, juiciness, texture, acidity, aromatic compounds, and nutrient composition1. For consumers, size and weight influence their purchasing decisions as these factors cater to different preferences. Also, postharvest storage options vary depending on the different lifespans of apples at various stages of ripeness, which is important for farmers and suppliers to consider. In addition, nutritionists consider the important and nutrients in apples, including fiber, vitamin C, and polyphenolic compounds, to be the indication of apple quality.

In these indicators, ripeness has also garnered increasing attention, with numerous studies2 highlighting its effects on postharvest storage, flavor, and nutritional composition. Rizzo et al. have shown that fruit ripeness profoundly affects its quality, influencing both external indicators (such as size, weight, and color) and internal indicators (including sweetness, crispness, juiciness, texture, acidity, aromatic compounds, and nutrient composition). Therefore, farmers employ various testing technology to determine the optimal ripeness of apples3,4. However, most testings currently rely heavily on manual visual inspections by apple ripeness assessors, which have several obvious limitations. Due to the variability in subjectivity among different assessors, manual visual inspection leads to inconsistent standards and consequently results in differing assessments of ripeness. Compounding this issue is the fact that the process is both time-consuming and labor-intensive, demanding substantial human resources and thereby escalating production costs. As apple cultivation expands and production scales up, enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of ripeness assessment has become a pressing challenge.

Recent advancements in machine learning have enabled accurate predictions of fruit ripeness5,6,7. Given the quality indicators, support vector regression (SVR)4,8 is widely utilized for its ability to handle complex, non-linear relationships and deliver robust predictions in fruit ripeness detection. However, the effectiveness of machine learning relies heavily on the optimization of their hyperparameters. To achieve optimal performance, various modern optimization techniques are employed, including traditional methods like probabilistic approaches such as Bayesian optimization9,10,11, grid and random search12,13, evolutionary algorithms like the whale optimization algorithm (WOA)14,15, grey wolf optimizer (GWO)16,17, and sparrow search algorithm (SSA)18,19, and game-theoretic methods such as Hyperband20. In particular, evolutionary algorithms are highly valued for their ability to simulate natural selection processes, which significantly enhances the accuracy and robustness of machine learning models used for predicting fruit ripeness. Additionally, ensemble algorithms that are less sensitive to hyperparameter settings, such as AdaBoost21,22, RandomForest23,24, GBDT25,26, XGBoost27,28, CatBoost29,30, also serve as viable alternatives.

Further, the approach of deriving maturity from unstructured data such as images, rather than from structured data gained more attention. It can reduce the need to generate quality indicators, streamlining the evaluation process. Convolutional neural network31 (CNN) based approaches have shown great potential in fruit assessments. CNN can learn features from images to classify and identify apples at different ripeness stages. Specifically on the detection task, YOLO (You Only Look Once) algorithm has been proposed and gained widespread application6 due to its mature one-stage design principle, which provides high accuracy and efficient object detection performance. Moreover, attention mechanisms are able to make models selectively focus on the most relevant aspects of input data. By facilitating the prioritization of significant features while diminishing the impact of less relevant information, attention mechanisms substantially enhance both prediction accuracy and computational efficiency.

The working pipeline is illustrated in Fig. 1, highlighting the primary contributions of this study:

-

Investigating the relationship between apple quality and both external and internal factors, underscoring the critical role of ripeness in determining overall quality, which reveals statistical insights into how ripeness affects quality metrics.

-

Utilizing an evolutionary algorithm combined with a support vector regression (SVR) model to systematically compare the performance of hyperparameter-optimized SVR models with hyperparameter-insensitive integrated algorithms for predicting apple maturity, achieving state-of-the-art (SOTA) performance.

-

Enhancing the accuracy of apple ripeness detection by integrating YOLO with an attention mechanism, reaching SOTA in detection accuracy and providing potential solution for automated apple quality assessment.

Materials and methods

Data sources

In this study, two datasets from the Kaggle (https://www.kaggle.com/) data science platform were utilized. The first dataset was provided by an unnamed American agriculture company. It comprises 4,000 structured text entries detailing both external indicators (size and weight) and internal indicators (sweetness, crunchiness, juiciness, ripeness, and acidity) of apple quality.

The structured text data in the first dataset includes quantitative and categorical variables. The publisher performed preliminary preprocessing during data collection, including the imputation of missing values and the removal of outliers. Subsequent normality testing confirmed that all variables followed a normal distribution. Detailed descriptions of these indicators are presented in Table 1.

The ripeness of apples is classified into three categories according to expert assessment: high-ripeness apples, medium-ripeness apples, and low-ripeness apples. This classification is widely used for tasks related to apple ripeness identification.

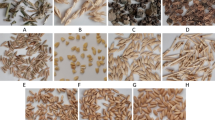

The second dataset consists of 650 images of apples at various stages of ripeness, captured in orchards against complex backgrounds. The ripeness of these apples is asassessed by experts based on a combination of internal and external indicators, as described in the first dataset. The number of apple samples labeled by ripeness category is shown in Table 2. The images vary in size and the size of the apples varies from image to image. And most images show apples on the tree that have not yet been harvested. Notably, some images capture multiple apple samples, leading to a higher number of samples than images.

Hyperparameter optimization-based regressor for predicting apple ripeness

Regressor

Support vector regression

Support Vector Regression (SVR)32 is a robust machine learning technique specifically designed to tackle regression problems based on mathematical statistics. SVR operates by constructing a linear function that maps indicators \(\:x\) to quality \(\:y\), minimizing the discrepancy between predicted quality \(\:f\left(x\right)\) and actual quality \(\:y\). The linear function can be written as:

where \(\:w\:\text{i}\text{s}\:\text{t}\text{h}\text{e}\:\text{w}\text{e}\text{i}\text{g}\text{h}\text{t}\:\text{c}\text{o}\text{e}\text{f}\text{f}\text{i}\text{c}\text{i}\text{e}\text{n}\text{t},\:x\) is the input feature vector, and \(\:b\) is the bias term. To mitigate the risk of overfitting, SVR adopts \(\:\epsilon\) insensitive loss function, which is defined as:

when the forecast error is less than a specified threshold \(\:\epsilon\), the loss is zero. Any error exceeding this threshold \(\:\epsilon\) contributes to the loss.

SVR then reduces the problem of finding the optimal \(\:w\) and \(\:b\) to solving the following optimization problems:

where \(\:{\xi\:}_{i}\) and \(\:{\xi\:}_{i}^{\text{*}}\) are slack variables that permit some data points to fall outside the \(\:\epsilon\) epsilon zone, providing a degree of tolerance in the predictions. The parameter \(\:C\) is a regularization factor used to regulate the training error. By solving the corresponding optimization problem, SVR can be constructed to accurately predict apple ripeness.

Ensemble algorithms

Ensemble algorithms, such as AdaBoost21,22, RandomForest23,24, GBDT25,26, XGBoost27,28, CatBoost29,30, are generally less sensitive to hyperparameter settings.

AdaBoost creates a strong learner by combining multiple weak regressor. AdaBoost adjusts the weights of samples based on the performance of previous regressor. The optimization formula is as follows:

where \(\:\alpha\:\) represents the weight of the weak learner, \(\:{w}_{i}\) denotes the weight of the weak learner.

RandomForest constructs an ensemble of decision trees, each trained on random subsets of data and features. RandomForest aggregates predictions from multiple treescombines to improve accuracy and reduce variance.

where T denotes the number of trees, and \(\:{Tree}_{t}\left(x\right)\) represents the prediction from the \(\:t\)-th tree.

GBDT builds trees sequentially where each tree aims to correct the residual errors of the previous trees using gradient descent. The optimization process in GBDT is analogous to that in CatBoost.

XGBoost is an advanced ensemble method that builds decision trees sequentially. Each tree corrects the errors of the previous ones, using gradient boosting to optimize the model. The optimization process is as follows:

where \(\:{T}_{k}\) represents the \(\:k\)-th tree of XGBoost, γ penalizes the number of leaves in the tree, λ is the L2 regularization parameter, and \(\:{w}_{k}^{j}\) denotes the weight of each leaf \(\:j\) in the \(\:k\)-th tree.

CatBoost handles categorical features efficiently using ordered boosting. It improves model performance by preventing overfitting and dealing with data directly. The optimization objective is described as:

where \(\:{w}_{j}\) is the weight of each leaf \(\:j\).

Evolutionary algorithms for regressor optimization

Whale optimization algorithm

Whale optimization algorithm (WOA)14,15 is inspired by whale foraging behavior and is used to optimize parameters in complex machine learning models. The principle is shown in Fig. 2, and key steps include:

Initialization Represent a population of model parameters. Each parameter is denoted as \(\:{x}_{i}\), where \(\:i\) is the \(\:i\)-th individual whale. The population is denoted as:

Fitness evaluation Update whale positions based on three behaviors.

-

Encircling prey:

where \(\:{X}^{\text{*}}\left(t\right)\) is the current best solution, \(\:A\) is the coefficient vector, and \(\:D\) is the distance vsctor.

-

Bubble-Net Attacking Method:

where \(\:{D}^{{\prime\:}}\) is the distance vector, and \(\:b\) and \(\:l\) are constant parameters.

-

Search for Pery:

where \(\:{X}_{\text{rand}}\left(t\right)\) is the randomly selected whale position.

Parameter optimization Use updated parameters to train the model, recalculate fitness values, and select the optimal parameter combination for model improvement.

Grey Wolf optimizer

Grey wolf optimizer (GWO)16,17 is a bio-inspired optimization algorithm designed based on the hunting behavior of grey wolves. As shown in Fig. 3, this algorithm mirrors the social hierarchy and cooperative hunting strategies observed in grey wolf packs. Within GWO, key entities include the alpha (\(\:\alpha\:\)), beta (\(\:\beta\:\)), and delta (\(\:\delta\:\)) wolves, which represent the top three optimal solutions, as well as the remaining wolves that assist in updating the positions of individuals in the population.

The updating of individual positions is based on simulating the hunting behavior of grey wolves, which is categorized into the following scenarios.

Top Wolves Selection In this context, \(\:{X}_{\alpha\:}\) represents the individual with the best fitness value, while \(\:{X}_{\beta\:}\) and \(\:{X}_{\delta\:}\) correspond to the second and third best individuals, respectively.

Other Wolve Position Update

where \(\:{X}_{\alpha\:}\), \(\:{X}_{\beta\:}\), and \(\:{X}_{\delta\:}\) are the positions of the \(\:\alpha\:\), \(\:\beta\:\), and \(\:\delta\:\) wolves, respectively. The vectors \(\:A\) and \(\:D\) represent the coefficient vector and distance vector r, respectively.

Sparrow search algorithm

Sparrow search algorithm (SSA)18,19 is a novel swarm intelligence optimization algorithm that mimics the foraging and vigilance behaviors of sparrows. As shown in Fig. 4, by initializing the population, defining a fitness function, and updating the positions of foragers and sentinels, SSA can effectively search for the optimal solution on a global scale. In this algorithm, producers focus on foraging food, while scroungers vigilance and protect against potential threats.

The position of each individual is updated by simulating the foraging and vigilance behaviors of sparrows, which is categorized into the following scenarios.

Forager Position Update

where \(\:{x}_{i}\left(t\right)\) represents the position of the \(\:\text{i}\)-th forager at generation \(\:t\), \(\:\alpha\:\) is a constant, and \(\:i\) is the index of the individual.

Discover Position Update

where \(\:{x}_{j}\left(t\right)\) represents the position of the \(\:j\)-th discoverer at generation \(\:t\), \(\:Q\) is a step size control parameter, and R is random number uniformly distributed in the range [0,1].

Sentinel Position Update

where \(\:{x}_{k}\left(t\right)\) represents the position of the \(\:k\)-th sentinel at generation \(\:t\), \(\:L\) is a constant, and \(\:{\text{x}}_{\text{best\:}}\left(\text{t}\right)\) is the position of the best individual in the current population.

Enhanced-YOLOv8 + model for apple localization and ripeness identification

Framework

To further enhance the prediction of apple ripeness, an Enhanced-YOLOv8 + model is designed to efficiently and accurately classify apples at different stages of ripeness. Empirical research indicates that integrating attention mechanisms with YOLO models yields considerable benefits across multiple applications. Specifically, in object detection tasks, this integration has been shown to improve performance by allowing the model to concentrate on key features. In the Enhanced-YOLOv8 + model, the backbone network first extracts deep features from the input apple images, which are resized at 640 × 640 pixels. Subsequently, the neck network integrates these extracted features, enabling the model to consolidate and utilize multi-scale feature information. This process enhances the effectiveness of the feature layers, resulting in three enriched feature layers. The final component, the head, is responsible for analyzing and interpreting each feature point on these layers to determine the object’s specific location, confidence level, and class. The Enhanced-YOLOv8 + framework is shown in Fig. 5, the main ones are Detect Efficient Head (ECA) and Efficient Channel Attention (DEH), apart from the backbone.

Detect efficient head

In this study, we introduce the Detect Efficient Head (DEH), a simplified version of the original, more complex detection head in YOLOv833. DEH is an advanced structure for object detection heads, designed to improve both the computational efficiency and detection accuracy of the model. In DEH, the tasks of classification and localization are processed through a shared network pathway, achieving efficient feature extraction and handling both classification and regression tasks. Additionally, efficient convolution operations are introduced, reducing computational cost and latency. Compared to original detection heads, DEH significantly enhances the model’s computational efficiency and real-time performance while maintaining high detection accuracy. These modifications make it particularly suitable for resource-constrained applications. In our ablation study, DEH demonstrates excellent performance and robustness in the apple quality prediction task.

Efficient channel attention

The Efficient Channel Attention (ECA)34 mechanism is an improved version of the Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE)35 attention mechanism, that specifically addresses the challenges associated with dimensionality reduction in channel attention. ECA enhances inter-channel interaction by directly applying a 1 × 1 convolution layer after global average pooling, which implies the dimensionality reduction step. Moreover, ECA employs an adaptive 1D convolution kernel, which improves the model’s ability to capture information across different channels. This results in enhanced efficiency and performance, while limiting the growth in the number of parameters.

As shown in Fig. 6, ECA facilitates cross-channel information interaction through a one-dimensional convolution, where the size of the convolution kernel is adaptively adjusted by a function. This allows layers with a larger number of channels to engage in more extensive cross-channel interaction. The adaptive function is defined as:

where \(\:\text{c}\) is the number of channels, \(\:{\upgamma\:}\) is a scaling factor, and b is an offset. This formulation ensures that the kernel size \(\:k\) adapts according to the number of channels, optimizing the model’s ability to capture inter-channel dependencies in a computationally efficient manner.

Lost function

Coefficient of determination for regression

This study employed the root mean square error (RMSE) as a key metric for model optimization. RMSE quantifies the average deviation between the predicted and actual values in the model. By assessing RMSE, the evaluation of how well the model captures the underlying patterns in the data can be conducted. A lower RMSE value indicates a better fit, suggesting that the model accounts for a larger portion of the variability observed in the dependent variable, as shown in Eq. 19:

Intersection over union measurement for object detection

Existing loss functions, including those based on Intersection over Union (IoU), have not fully addressed the issue of accurately predicting bounding boxes, which often results in slow model convergence and lower prediction accuracy. Additionally, traditional loss functions tend to overlook the imbalance between positive and negative samples, causing predictions with minimal overlap with the target box to disproportionately affect the loss value. To address these issues, the Enhanced IoU (EIoU) loss function is used in this study, which is expressed as:

where \(\:{b}^{gt}\) and \(\:{b}^{p}\) represent the center coordinates of the ground truth box and the predicted box, respectively, \(\:{w}^{c}\) and \(\:{h}^{c}\) are the width and height of the smallest enclosing rectangle that covers both the predicted and ground truth boxes, \(\:d\left({b}^{p},{b}^{gt}\right)\) denotes the Euclidean distance between these two center points. Similarly, \(\:{\text{*}}^{p}\) and \(\:{\text{*}}^{gt}\) denote the corresponding parameters (width and height) of the predicted and ground truth boxes. \(\:d\left({w}^{p},{w}^{gt}\right)\) indicates the difference in width between the predicted and ground truth boxes, \(\:d\left({h}^{p},{h}^{gt}\right)\) indicates the difference in height between the predicted and ground truth boxes.

Experimental setup

Regressor for predicting Apple ripeness

To evaluate the performance of the apple ripeness prediction model, we constructed a database containing 4,000 samples, which was then divided into a training set and a testing set in a 7:3 ratio. Specifically, 70% of the data was randomly selected for training the model, while the remaining 30% was used for testing, ensuring the model’s generalization capability. Additionally, a five-fold cross-validation approach was employed as the objective function for model optimization.

This study employed several metrics, including root mean square error(RMSE), coefficient of determination(\(\:{\text{R}}^{2}\)), mean absolute error(MAE), and variance accounted for(VAF), to assess the model’s performance in predicting apple ripeness. RMSE is measuring the average deviation between the predicted values and the actual values. R2 indicates the fraction of the overall variability in the dependent variable that is accounted for by the model. MAE is measuring the average absolute deviation between the predicted values and the actual values. VAF indicates the percentage of the total variance that is explained by the model.

The SVR model demonstrates significant advantages in handling outliers and continuous variables, making it an effective method for addressing both regression and classification problems. Given the widespread popularity of the Support Vector Regression (SVR) model for its exceptional performance and minimal reliance on feature engineering, this study adopted an SVR model based on Gradient Boosting Trees.

YOLO for Apple localization and ripeness identification

To enhance the model’s generalizability and robustness, this study utilized various data augmentation techniques, including image cropping, translation, rotation, and brightness adjustment, to expand the original dataset while maintaining class balance. The original dataset consisted of 650 images, distributed across three ripeness categories: High-Ripeness (241 images), Medium-Ripeness (215 images), and Low-Ripeness (234 images). These augmentation techniques were applied equally across all categories, increasing the dataset size by 3.2 times to a total of 2,160 images.

The augmented dataset was divided into training, validation, and testing sets in an 8:1:1 ratio, ensuring each subset preserved the class balance of the original dataset. For model evaluation, the mean Average Precision (mAP) at a threshold of 0.50 (mAP@50) was employed as the primary performance metric. This metric evaluates the precision-recall trade-off for image classification at a confidence threshold of 0.50, ensuring robust assessment of the model’s capability to differentiate ripeness categories. This approach mitigates the risk of overfitting by exposing the model to a more diverse range of scenarios while improving its adaptability to unseen data. To enhance the model’s generalizability and robustness, this study utilized various data augmentation techniques, including image cropping, translation, rotation, and brightness adjustment, to expand the original dataset while maintaining class balance. The original dataset consisted of 650 images, distributed across three ripeness categories: High-Ripeness (241 images), Medium-Ripeness (215 images), and Low-Ripeness (234 images). These augmentation techniques were applied equally across all categories, increasing the dataset size by 3.2 times to a total of 2,160 images.

To evaluate the model’s performance, this study employed three key metrics: Recall, Precision, and mean Average Precision at a threshold of 0.50 (mAP@50). These metrics provide a robust assessment of the model’s classification capabilities and are defined as follows:

where TP (True Positives) represents the correctly identified samples, FN (False Negatives) refers to the samples incorrectly classified as negative, and FP (False Positives) refers to the samples incorrectly classified as positive.

mAP@50 is calculated as the mean of the Average Precision (AP) values across all classes, where AP is defined as the area under the Precision-Recall ( \(\:\text{P}-\text{R}\) ) curve. Specifically, at a confidence threshold of 0.50, the mAP is computed as:

here, \(\:\text{P}\left(\text{r}\right)\) denotes Precision as a function of Recall, and \(\:\text{N}\) represents the total number of classes.

The Recall curve, Precision curve, and mAP@50 curve were generated to visualize and analyze the model’s performance comprehensively. These visualizations highlight the tradeoffs between precision and recall at different thresholds and provide insights into the model’s robustness.

The experiments were running an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4070 GPU and a 13th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-13700 H 2.40 GHz CPU, with the CUDA toolkit 12.0. The models were optimized using the Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) optimizer, with the number of training epochs set to 100 and a batch size of 32. To thoroughly assess the performance of the proposed models, Precision, Recall, and mean Average Precision (mAP@50) were chosen as the key evaluation metrics.

Results

To provide a clear overview of the experimental setups and ensure readability, Table 3 summarizes the various scenarios, models, and configurations evaluated in this study. This table serves as a guide to the subsequent sections, where the performance of each model on structured and unstructured data is analyzed in detail.

Regressor performance in structured text data

Statistical discrepancy

In this study, apple quality was treated as the dependent variable, while apple size, weight, and sweetness were considered as independent variables. The analysis using a decision tree model identified several key factors influencing apple quality, with ripeness (0.212646) being the most significant. This indicates that optimal harvesting timing is crucial for quality. Following ripeness, sweetness (0.174194) and acidity (0.159374) were also found to be important, as they directly affect flavor perception and consumer satisfaction. Juiciness (0.125678) contributes significantly to the overall eating experience, while size (0.147088) has a moderate influence on market appeal. In contrast, weight (0.095164) and crunchiness (0.085855) showed the least impact on quality perception.

Furthermore, to explore the relationships among the quantitative variables, scatterplot matrices and performed Pearson correlation analysis was generated, as shown in Fig. 7. The analysis revealed that the maximum correlation among the indicators was only 0.32 (in absolute value), indicating relatively weak linear relationships between the variables. This suggests that while there are some associations among the factors affecting apple quality, they may not be strongly interrelated, emphasizing the complexity of quality determination in apples.

Predicted analysis

For constructing the SVR models, hyperparameter optimization-based evolutionary algorithms was conducted. The aforementioned models—WOA-SVR, GWO-SVR, and SSA-SVR—were evaluated. Due to the inherent challenges in determining optimal parameter settings for heuristic optimization algorithms, random numbers within their effective ranges were utilized to achieve improved results, as shown in Table 4; Fig. 8. After determining the optimal population sizes for the heuristic algorithms, this study also considered other models to compare the performance of the established models.

Each model was evaluated and compared using the same testing dataset to ensure the reliability and consistency of the performance assessment (Table 5). The results indicate that Random Forest performed the best on the training set, achieving a total ranking score of 32, demonstrating strong model fitting capabilities. However, on the test set, the WOA-SVR model stood out, achieving the highest total ranking score of 32, showcasing its exceptional generalization ability. The final optimized parameters for the SVR model using WOA were as follows: penalty coefficient C of 10.03341409, epsilon \(\:{\epsilon}\) in the loss function of 0.342657572, and kernel function parameter \(\:{\upgamma\:}\) of 0.059225195.

Although GWO-SVR and SSA-SVR performed slightly less well than Random Forest on the training set, they both exhibited better performance on the test set, with total ranking scores of 28 and 24, respectively. In contrast, traditional machine learning models such as XGBoost, CatBoost, and AdaBoost performed relatively poorly on both the training and test sets.

Based on the apple ripeness prediction results and their associated relationships (Fig. 9), the SVR models based on optimization algorithms, particularly the WOA-SVR, demonstrated higher applicability and stability in the task of apple ripeness prediction.

Object detection performance in image data

Apple localization and apple ripeness identification

To further evaluate the performance of the models used in this study, common object detection models such as YOLOv336, YOLOv537, and YOLOv638 were selected for a comparative experiment. The experiments were conducted under the same configuration environment on the same apple dataset, and the results are presented in Table 6. By comparing YOLOv3-tiny, YOLOv5n, YOLOv5s, YOLOv6, YOLOv8s, and the improved model under identical conditions, this study aimed to gain deeper insights into the performance differences of each model in the task of apple ripeness detection.

The experimental results reveal that the improved model (ours) outperformed the other models in terms of accuracy, recall, and mAP@50. Among the compared models, YOLOv3-tiny performed relatively well, especially in terms of mAP@50, where it closely approached the performance of the improved model, demonstrating its strong capabilities as a lightweight model. The YOLOv5 series models showed consistent performance, exhibiting high accuracy and recall rates, although their mAP@50 values were slightly lower than those of YOLOv3-tiny and the improved model. YOLOv6 performed the worst, primarily due to its network architecture and optimization strategy not being fully aligned with the specific requirements of the apple ripeness detection task. YOLOv8s, a variant of YOLOv8, exhibited performance similar to that of YOLOv3-tiny, further confirming the potential of the YOLOv8 model in apple ripeness detection tasks.

Insight visualization

The results of experiments utilizing the Enhanced-YOLOv8 + model for apple ripeness recognition in various scenarios are presented. These experiments encompass: (a) a single apple, (b) multiple apples with the same ripeness, (c) multiple apples with the same ripeness but partially occluded, (d) and multiple apples with different ripeness in a packaging environment. In each scenario, the model demonstrates high accuracy and robustness. Comparing the recognition performance across these scenarios further validates the adaptability and effectiveness of the Enhanced-YOLOv8 + model in complex settings. Notably, the model’s performance in detecting apples under occlusion and varying ripeness conditions in the packaging environment, as shown in Fig. 10, significantly surpasses that of traditional methods, highlighting its robustness and generalization capabilities beyond the orchard harvesting scenes present in the training set.

Discussion

Ablation of evolutionary algorithms for regressor optimization

To evaluate the effectiveness of evolutionary algorithms in optimizing the regressor, the SVR model’s relevant hyperparameters, including penalty coefficient C, epsilon \(\:{\epsilon}\), and kernel function parameter \(\:{\upgamma\:}\), were initialized, and the parameters for the WOA algorithm were set. Specifically, the logarithmic spiral constant \(\:\text{b}\) was set to 1, \(\:\text{L}\) was assigned a random number within the range of [-1, 1], and \(\:\text{r}\) was set within the range of [0, 1]. The population size was subsequently varied at 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, and 300. During the optimization process, the model was trained on the training set and validated on the test set to ensure the validity of the results and to streamline the process.

Analyzing the fitness curves of the various heuristic algorithms, it was observed that the WOA-SVR model exhibited rapid convergence and achieved a lower final fitness value with a population size of 250, indicating superior optimization performance. The GWO-SVR model, when using a population size of 250, demonstrated the lowest fitness value and a more stable convergence trend, suggesting that a larger population size is more effective within the GWO algorithm. Conversely, the SSA-SVR model attained the lowest fitness value and the fastest convergence speed with a population size of 200, highlighting the optimal model performance and optimization effect of the SSA algorithm under these conditions (Fig. 11). Overall, larger population sizes across all three optimization algorithms yielded better model performance and lower fitness values, with the most pronounced effect observed in the WOA-SVR model.

The performance of the WOA-optimized SVR model varied significantly across different population sizes on the test set. Among the configurations tested, the model with a population size of 150 achieved the best results, with the lowest RMSE, the highest VAF, and strong R2 and MAE values. This configuration secured a total ranking score of 24, placing it first overall in the comparison (Table 7). These results highlight the importance of selecting an appropriate population size to optimize model performance.

For the GWO-SVR model, after initializing the SVR model’s parameters, the convergence factor of the GWO algorithm was set to decrease linearly from 2 to 0. The population size was varied across 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, and 300, while all other training and testing conditions were kept consistent with those used for the WOA-SVR model.

The performance of the GWO-optimized SVR model showed significant differences across various population sizes on the test set. The model with a population size of 250 achieved the best performance, with an RMSE of 1.08006, an MAE of 0.71802, an R2 of 0.66674, and a VAF of 66.678, earning a total ranking score of 24 and securing the top position (Table 8). In contrast, the model with a population size of 300 exhibited the poorest performance on the test set, with the lowest total ranking score of 6. These results highlight the critical impact of population size on the optimization process and the overall predictive accuracy of the GWO-SVR model.

For the SSA-SVR model, after initializing the SVR parameters, the SSA parameters were set as follows: disturbance factors r1 and r2 were set to 0.5 and 1, respectively, and the escape probability pp was set to 0.2. The remaining parameter settings, as well as the testing conditions, were consistent with those used for the WOA-SVR model.

The performance of the SSA-optimized SVR model exhibited significant variation across different swarm sizes on the test set. Among them, the model with a swarm size of 200 achieved the best performance, with an RMSE of 1.08011, an R2R2 of 0.66671, an MAE of 0.71809, and a VAF of 66.675. This configuration secured the highest total ranking score of 24, placing it first overall (Table 9). In comparison, the model with a swarm size of 300 performed relatively poorly, achieving a total ranking score of 16, reflecting a lower predictive accuracy.

Ablation of enhanced-YOLOv8 + model for apple localization and ripeness identification

To validate the effectiveness of the three proposed improvements, an ablation study was conducted on a unified dataset under identical configuration conditions. The experiments introduced the following modifications to the base YOLOv8 model: (a) replacing the standard head structure with the Detect Efficient Head (DEH), (b) integrating the Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) module, and (c) substituting the standard loss function with the Enhanced IoU (EIoU) loss function.

The training curves for the models are shown in Fig. 12. The loss curves demonstrate that the improved models, which incorporate DEH (head structure replacement), the ECA module, and the EIoU loss function, exhibit faster convergence and lower loss values during training, with the YOLOv8 + A + B + C model performing the.

best. The Recall curves indicate that the improved models experience rapid increases in recall during the initial stages of training, stabilizing later on, with the YOLOv8 + A + B + C model achieving the highest recall rate. The Precision curves highlight the improvement in accuracy for all models, showing that the precision of the improved models is higher in the latter stages of training, with the YOLOv8 + A + B + C model again demonstrating the best precision.

The mAP@50 curves illustrate a significant improvement in mean average precision for the modified models, with the YOLOv8 + A + B + C model attaining the highest mAP@50 value. These results further validate the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed modifications. In summary, the models incorporating the DEH, ECA module, and EIoU loss function outperformed the original YOLOv8 model across all metrics, with the YOLOv8 + A + B + C model exhibiting the best overall performance (Table 10).

The results indicate that the initial YOLOv8 model achieved an accuracy of 91.4%, a recall rate of 90.8%, and an mAP@50 value of 94.6%. By incorporating the modifications A (EDH), B (ECA), and C (EIoU) into the model, varying degrees of performance improvement were observed. Notably, when combining strategies A and B, the model’s accuracy increased to 93.5%, the recall rate to 95.9%, and the mAP@50 value to 97.6%, demonstrating a significant enhancement in performance. When integrating all three improvement strategies, the model’s performance was further optimized, achieving an accuracy of 93.9%, a recall rate of 95.4%, and an mAP@50 value of 97.9%. These results suggest that the comprehensive model, incorporating all three improvement strategies, outperforms the original model, with improvements of 2.5% in accuracy, 4.6% in recall, and 3.3% in mAP@50.

Given that the dataset used in this study is divided into three labels, a comparative analysis of the average precision across different labels was conducted to evaluate the model’s effectiveness and generalization capability. The results, as shown in Table 11, highlight potential causes for significant deviations in precision and suggest areas for future improvement. The analysis reveals that the precision and recall for high-ripeness apples (apple-H) and medium-ripeness apples (apple-M) are consistently higher than those for low-ripeness apples (apple-L), suggesting that ripened apples are more easily detected due to their distinct features. In contrast, low-ripeness apples exhibit lower precision and recall, which may reflect the inherent difficulty in distinguishing their less pronounced characteristics. This observation highlights the need for targeted improvements in the detection of low-ripeness apples to enhance overall model performance.

The observed difference in precision is likely due to the fact that the features of unripened apples are more challenging to distinguish in images. Ripeness apples tend to have more pronounced color, size, and shape characteristics, making them easier to identify, whereas the features of unripened apples are less distinct or exhibit greater variability, increasing the difficulty of detection. Therefore, improving the detection accuracy for unripened apples is critical for enhancing the overall performance of the model.

Conclusions

This study integrates evolutionary algorithms with support vector regression (SVR) and proposes an Enhanced-YOLOv8 + model to assess apple quality, emphasizing the critical role of ripeness in agricultural production. By leveraging both structured and unstructured data, the study evaluates and compares the suitability of different models and techniques for apple ripeness classification.

For structured data, several regression models were evaluated, including SVR combined with various optimization algorithms (WOA-SVR, GWO-SVR, SSA-SVR), as well as tree-based models such as XGBoost, CatBoost, AdaBoost, GBDT, and Random Forest. Among these, WOA-SVR demonstrated the best performance in predicting apple ripeness, achieving the highest R2 value and accuracy on the test set. While GWO-SVR and SSA-SVR slightly underperformed compared to Random Forest on the training set, both models outperformed Random Forest on the test set, demonstrating better generalization capabilities. In contrast, XGBoost, CatBoost, and AdaBoost exhibited relatively poor performance on both training and test sets, highlighting their limitations in this specific task.

For unstructured data, the study tested an Enhanced-YOLOv8 + model with various strategies, including the use of the Detect Efficient Head (DEH), the Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) module, and the Enhanced IoU (EIoU) loss function. The incorporation of these techniques significantly improved the model’s ability to localize and identify ripeness levels from image data. The Enhanced-YOLOv8 + model achieved remarkable results, with an accuracy of 93.9%, a recall rate of 95.4%, and an mAP@50 score of 97.9%, demonstrating its robustness in handling unstructured datasets.

This study not only improves the accuracy of ripeness prediction but also provides a comprehensive solution for apple quality assessment by integrating structured and unstructured data analysis. While both structured and unstructured datasets have their respective advantages, their suitability depends on the application context. SVR-based methods with structured datasets are more straightforward to implement, require less computational power, and are ideal for scenarios with tabular data, such as postharvest quality assessments. In contrast, CNN-based methods excel in handling unstructured image data, making them more suitable for applications like automated sorting systems in industrial settings. Considering scalability and real-time applicability, CNN-based methods, particularly the Enhanced-YOLOv8 + model, offer greater potential for commercialization in large-scale agricultural operations.

Data availability

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.kaggle.com/.

References

Musacchi, S. & Serra, S. Apple fruit quality: overview on pre-harvest factors. Sci. Hort. 234, 409–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2017.12.057 (2018).

Rizzo, M., Marcuzzo, M., Zangari, A., Gasparetto, A. & Albarelli, A. Fruit ripeness classification: A survey. Artif. Intell. Agric. 7, 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aiia.2023.02.004 (2023).

Jiménez, A. R., Jain, A. K., Ceres, R. & Pons, J. L. Automatic fruit recognition: a survey and new results using Range/Attenuation images. Pattern Recogn. 32(10), 1719–1736. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-3203(98)00170-8 (1999).

Gongal, A., Amatya, S., Karkee, M., Zhang, Q. & Lewis, K. Sensors and systems for fruit detection and localization: A review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 116, 8–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2015.05.021 (2015).

Jiménez, A. R., Ceres, R. & Pons, J. L. A survey of computer vision methods for locating fruit on trees. Trans. ASAE. 43(6), 1911–1920. https://doi.org/10.13031/2013.3096 (2000).

Knott, M., Perez-Cruz, F. & Defraeye, T. Facilitated machine learning for image-based fruit quality assessment. J. Food Eng. 345, 111401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2022.111401 (2023).

Hameed, K., Chai, D. & Rassau, A. A comprehensive review of fruit and vegetable classification techniques. Image Vis. Comput. 80, 24–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imavis.2018.09.016 (2018).

Ajin, R. S., Segoni, S. & Fanti, R. Optimization of SVR and catboost models using metaheuristic algorithms to assess landslide susceptibility. Sci. Rep. 14, 24851. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72663-x (2024).

Mockus, J. Bayesian Approach to Global Optimization: Theory and Applications. Mathematics and Its Applications, Vol. 37 (Springer, 1989). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-0909-0

Candelieri, A., Ponti, A. & Archetti, F. Fair and green hyperparameter optimization via multi-objective and multiple information source bayesian optimization. Mach. Learn. 113, 2701–2731. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10994-024-06515-0 (2024).

Yang, K., Liu, L. & Wen, Y. The impact of bayesian optimization on feature selection. Sci. Rep. 14, 3948. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54515-w (2024).

Bergstra, J. & Bengio, Y. Random search for hyper-parameter optimization. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 13(10), 281–305 (2012).

Rimal, Y., Sharma, N. & Alsadoon, A. The accuracy of machine learning models relies on hyperparameter tuning: student result classification using random forest, randomized search, grid search, bayesian, genetic, and optuna algorithms. Multimedia Tools Appl. 83, 74349–74364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-024-18426-2 (2024).

Mirjalili, S. & Lewis, A. The Whale optimization algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 95, 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2016.01.008 (2016).

Punia, P., Raj, A. & Kumar, P. An enhanced Beluga Whale optimization algorithm for engineering optimization problems. J. Syst. Sci. Syst. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11518-024-5608-x (2024).

Mirjalili, S., Mirjalili, S. M. & Lewis, A. Grey Wolf optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 69, 46–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2013.12.007 (2014).

Yang, Z. & Ma, J. DEGWO: a decision-enhanced grey Wolf optimizer. Soft. Comput. 28, 11207–11236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-024-09878-7 (2024).

Xue, J. & Shen, B. A novel swarm intelligence optimization approach: sparrow search algorithm. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 8(1), 22–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642583.2019.1708830 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. An improved density peaks clustering based on sparrow search algorithm. Cluster Comput. 27, 11017–11037. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10586-024-04384-9 (2024).

Li, L., Jamieson, K., DeSalvo, G., Rostamizadeh, A. & Talwalkar, A. Hyperband: A novel Bandit-Based approach to hyperparameter optimization. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 18(185), 1–52 (2018).

Freund, Y. & Schapire, R. E. A desicion-theoretic generalization of on-line learning and an application to boosting, in Computational Learning Theory, (ed Vitányi, P.) Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-59119-2_166. (1995).

Zhang, Y. et al. AdaBoost model for rockburst intensity prediction considering class differences and quantitative characterization of misclassification difference. Sci. Rep. 14, 28232. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79141-4 (2024).

Ho, T. K. Random decision forests. in Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition 278–282. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDAR.1995.598994 (1995).

Bai, X. et al. Multivariate temperature prediction model based on CNN-BiLSTM and randomforest. J. Supercomputing. 81, 162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-024-06689-3 (2025).

Friedman, J. H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Annals Stat. 29(5), 1189–1232. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1013203451 (2001).

Wang, L. Z. et al. Transformer fault diagnosis method based on SMOTE and NGO-GBDT. Sci. Rep. 14, 7179. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-57509-w (2024).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining in KDD ’16 785–794 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785

Yx. Liu, Y. et al. Application of XGBoost and kernel principal component analysis to forecast oxygen content in ESR. J. Iron. Steel Res. Int. 31, 2940–2952. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42243-024-01205-6 (2024).

Prokhorenkova, L., Gusev, G., Vorobev, A., Dorogush, A. V. & Gulin, A. CatBoost: unbiased boosting with categorical features. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems(eds. Bengio, S. et al.) (Curran Associates, Inc., 2018). https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2018/file/14491b756b3a51daac41c24863285549-Paper.pdf.

Li, H. et al. Research on mine water source classifications based on BO-CatBoost. Environ. Monit. Assess. 196, 876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-024-13040-z (2024).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521(7553), 436–444. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14539 (2015).

Drucker, H., Burges, C. J. C., Kaufman, L., Smola, A. & Vapnik, V. Support vector regression machines. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems(eds. Mozer, M. C. et al.) (MIT Press, 1996). https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/1996/file/d38901788c533e8286cb6400b40b386d-Paper.pdf.

Varghese, R. and S. M., YOLOv8: A novel object detection algorithm with enhanced performance and robustness. in International Conference on Advances in Data Engineering and Intelligent Computing Systems (ADICS) 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/ADICS58448.2024.10533619 (2024).

Wang, Q. et al. ECA-Net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 11531–11539. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.01155 (2020).

Hu, J., Shen, L. & Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 7132–7141. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2018.00745 (2018).

Redmon, J. & Farhadi, A. YOLOv3: An Incremental Improvement. arXiv. ArXiv:1804.02767 (2018).

Jocher, G. et al. ultralytics/yolov5: v7.0 - YOLOv5 SOTA Realtime Instance Segmentation (Zenodo, 2022). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7347926

Li, C. et al. YOLOv6: A Single-Stage Object Detection Framework for Industrial Applications. arXiv. ArXiv:2209.02976 (2022).

Funding

“This research was funded by China University of Labor Relations College Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Funding, grant number s202412453027”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L., A.Y., X.Y. and Z.W.; methodology, Y.L. and Z.W.; software, Y.L. and X.Y.; validation, Y.L.; formal analysis, Y.L.; investigation, Y.L. and A.Y.; resources, Y.L. and A.Y.; data curation, Y.L. and X.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L., A.Y., X.Y. and Z.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.L.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, Y.L.; project administration, Y.L.; funding acquisition, Z.W. Y.L. and Z.W. as joint first contributors, A.Y. and X.Y. as joint second contributors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Wang, Z., Yang, A. et al. Integrating evolutionary algorithms and enhanced-YOLOv8 + for comprehensive apple ripeness prediction. Sci Rep 15, 7307 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91939-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91939-4