Abstract

Previous epidemiological studies have associated various body-related indicators with arthritis; however, the results have been inconclusive. Therefore, this research aimed to develop and validate a nomogram model for predicting the risk of arthritis using easily available indicators and to assess the model’s predictive performance. Cross-sectional data were collected from 3660 participants in the 2021–2023 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. The research conducted variable selection and model development using the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator regression model and multivariate logistic regression analysis, and the performance of the nomogram was validated. The nomogram model incorporated nine independent predictors: age, sex, family poverty-income ratio, race, diabetes status, vitamin D level, systemic immunity-inflammation index, and waist-to-height ratio. After validation, it has been proven that the nomogram model has good performance. The nomogram model developed in this study effectively predicts the risk probability of arthritis in the general population of the United States. All variables included in this nomogram can be easily obtained from the population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Arthritis is a musculoskeletal condition that commonly leads to disability and significantly impacts the quality of life of those affected1. It not only causes pain and affects physical functioning but is also associated with various other outcomes, including mental health issues, sleep disturbances, work limitations, and even mortality2. Currently, more than 300 million people worldwide suffer from arthritis, and its prevalence continues to rise3. Despite this, there is still a lack of effective medications to halt the progression of arthritis. The high prevalence of arthritis and its associated complications4, such as joint injuries and disability, place an increasing burden on the global public health system5.

Arthritis affects women more than men, and the risk of developing the disease increases with age6. This leads to a reduction in quality of life in older adults, placing an increased burden on them, their families, and society as a whole.7,8. Therefore, it is important to identify potential high-risk populations in the early stages of arthritis onset to achieve the goals of prevention and relief.

Among the risk factors for arthritis, according to current research, risk factors can be divided into two categories: joint level and individual level9. The joint level refers to the degree of loading on the joints, while individual factors include age, sex, obesity, and various indicators. Emerging evidence indicates that systemic inflammation serves as a critical factor in the pathogenesis of various forms of arthritis10,11. The systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) is used as an indicator of the systemic inflammatory response, and in recent years, its field of application has expanded. An increasing number of studies suggest that the SII can also be used to predict the severity of certain diseases and monitor the effectiveness of treatments12.

Moreover, recent studies have demonstrated that the non-HDL cholesterol to HDL cholesterol ratio (NHHR) is associated with several diseases, such as periodontitis13 and diabetes14, among which diabetes is a risk factor for arthritis15. Few studies have examined the possible association between the NHHR and arthritis. In addition, a growing number of studies have linked adipokines from obesity to the development of arthritis16. Some studies have shown that certain body mass indices of obesity are associated with arthritis4,17,18, especially those that differ from traditional obesity indices (BMI), such as the weight-adjusted-waist index (WWI), waist-to-height ratio (WHtR), and other obesity indices, which also incorporate the calculation of waist circumference. These indicators are easier to measure and detect than the adiposity factor due to obesity.

At present, the relationship between various indicators and arthritis still needs to be verified. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the relationship between different obesity indicators, NHHR, and SII and the risk of arthritis, identify the factors that have the greatest impact on arthritis, develop a new nomogram, and provide new methods for predicting arthritis.

Materials and methods

Study population and data

The survey study population was obtained from NHANES, a public database collected and maintained by the CDC in the United States. The data are updated biennially and have been essentially continuous from 1999 to 2020. Due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, data collection was suspended from March 2020 to July 2021 and resumed in August 2021. The data were collected from the U.S. population aged 20 years and older. This study used data from August 2021 to August 2023, and the survey was a cross-sectional study of U.S. residents aged 20 years or older. According to the content of this study, the data was screened and the exclusion criteria are as follows: (1) participants under 20 years of age; (2) participants who did not complete the obesity indicator test and the arthritis questionnaire; and (3) participants with missing covariate data. After manual data screening, 3,660 participants were ultimately selected for analysis, as shown in Fig. 1. A total of 3,660 participants were enrolled, with 1,234 of them diagnosed with arthritis.

Definition of a variable

The outcome variable in this study was the incidence of arthritis, which was ascertained through the questionnaire item: "Have you ever been diagnosed with arthritis?" After reviewing the literature, this study selected confounding variables that could affect arthritis, including sex, race, education level, family poverty-income ratio (PIR), age (grouped as 20–39, 40–59, 60 +), and drinking status (participants who answered “yes” to the questionnaire were considered drinkers). Smoking status was based on the questionnaire response to having smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime (participants who answered “yes” were considered smokers)19. Hypertension and diabetes status were also based on participants’ affirmative responses to the questionnaire.

Trained technicians measured the height, weight, and waist circumference (WC) of all participants. The total serum 25(OH)D concentration was calculated as the sum of 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3 and grouped into quartiles20: Group 1 (0–57.3 nmol/L), Group 2 (57.4–78.5 nmol/L), Group 3 (78.6–103.0 nmol/L), and Group 4 (above 103.0 nmol/L). After a fasting period of at least 8 h, blood samples were systematically collected from participants, including measurements of triglyceride (TG) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels, for comprehensive examination. The formulas for calculating BMI, WHtR, WWI, SII, NHHR, conicity index (CI), and A body shape index (ABSI) are outlined below21:

The factors in the SII calculation formula are all derived from peripheral blood, and the fourteen indicators chosen for this investigation can be obtained through straightforward anthropometric measurements and basic blood chemistry analyses. Detailed measurement procedures using the study variables are available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.

Development and validation of machine learning prediction models

In this study, Python 3.12.3 (https://www.python.org) was used to build the models. The dataset was divided into training and testing sets with a 7:3 ratio, and the Random Forest (RF) algorithm was applied for model construction. A prediction model was built using the training set and evaluated on the test set. A 500-fold repeated cross-validation method was employed, and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) was calculated for the subjects. Finally, the optimal model was explained using SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to assess the impact of each variable on the prediction results. A SHAP dependency graph was created to illustrate the relationship between the predictor and the dependent variable.

Statistical methods

Data analysis was conducted using R 4.4.1 software (http://www.R-project.org) and SPSS version 26.0 (https://www.ibm.com/spss). Continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations, with Student’s t-tests used to determine differences between groups. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies (n) and percentages (%), and group comparisons were conducted using either the chi-square test.

Moreover, the relationships between arthritis and other variables were examined through least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression analysis. This method was employed to reduce the dimensionality of the data and identify the most valuable predictors. Variables with coefficients that contributed minimally to the overall model were reduced to zero, thereby ensuring the predictive accuracy of the model27. The data were divided 7:3 into training and test sets. The training set was used for nomogram model development, and the test set was used for the final generation of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, calibration curves, and decision curve analysis (DCA) to evaluate the performance of the model and assess the predictive effectiveness of the training and test sets, respectively.

On the basis of the regression coefficients of logistic regression, a nomogram was constructed for all the factors, and the ROC curve was used to evaluate the discriminative ability of the nomogram28. The predictive abilities of the RF model and the nomogram model were compared, and the model with the highest AUC value was selected as the final model. A calibration curve was used to assess the fit between the predicted probabilities and the actual probabilities of the final model29. Finally, DCA was plotted, as the DCA curve avoids the critical value, sensitivity, and specificity issues that may be associated with the ROC curve, and the net benefit of the final model in a clinical setting was directly calculated30. Significant levels were determined by a P-value ≤ 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

In this study, 3,660 participants were identified as the final study population (Fig. 1). The demographic characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. Among the non-arthritic patients, 1,171 (48.3%) were male and 1,255 (51.7%) were female, with a mean age of 48.1 ± 16.6 years, and their mean SII was 511 ± 307. Among the arthritic patients, 505 (40.9%) were male and 729 (59.1%) were female, with a mean age of 63.5 ± 11.7 years, and the mean SII was 617 ± 438. Table 1 also shows a detailed baseline for other variables, and except for PIR, all other variables showed significant differences (P < 0.05).

Model development and selection

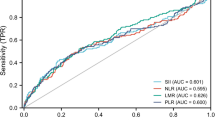

ROC curves were constructed to assess the individual predictive effects of all variables on arthritis (Fig. 2). It can be seen that, when predicting arthritis independently, the top five variables with the best results are age, WWI, ABSI, SII, and WHtR. BMI is not included among them.

The LASSO regression model analyzed a total of 23 variables and selected the best variables based on the value of λ (Fig. 3). The 12 selected variables were entered into the logistic regression equation. After using the stepwise backward method to exclude variables with P > 0.05 in the logistic regression equation, a total of nine variables were ultimately included in the logistic regression (Table 2).

Based on the final model, a nomogram was constructed for predicting arthritis. The risk factors included age, sex, PIR, race, the occurrence of diabetes, vitamin D levels, the SII, and the WHtR (Fig. 4).

The AUC of the nomogram model is 0.784 (Fig. 5A), while the AUC of the random forest model is 0.771 (Fig. 5B). Therefore, the nomogram model was selected as the final prediction model.

Model interpretation and validation

The SHAP values of different variables in the random forest model were calculated to generate a variable importance ranking chart (Fig. 6A) and SHAP dependence plots (Fig. 6B). As shown in Fig. 6A, age, WHtR, and vitamin D content are among the top three most important variables for predicting the risk of arthritis. The SHAP dependence plots further illustrate the influence of variables on model predictions, with Fig. 6B displaying the SHAP values associated with WHtR and arthritis. A WHtR of 0.6 is identified as the critical threshold for the occurrence of arthritis, and as WHtR increases, the risk of developing arthritis also rises, demonstrating a non-linear positive correlation between WHtR and the incidence of arthritis.

Based on the nomogram model, calibration curves (Fig. 7A) and DCA (Fig. 7B) were plotted. The calibration curve indicates a strong consistency between the predicted and observed results. The DCA curve shows that the net benefit probability ranges from 0 to 65%, suggesting that the model has significant predictive power for arthritis. Additionally, the predictive model demonstrated good discriminative ability, high accuracy, and potential clinical benefits in the validation set.

Discussion

This study developed a nomogram model consisting of nine predictive factors to assess the risk of arthritis. After validating the model’s effectiveness, it demonstrated good predictive value and could provide more precise risk stratification for potential high-risk populations.

Arthritis is currently a significant public health problem, with obesity31, dietary intake, type 2 diabetes, and inflammatory conditions widely recognized as influencing its development. Among these factors, the association between BMI and arthritis has been extensively studied, but BMI is not a good indicator of fat distribution in the body32. Studies have shown that BMI has a J-shaped association with all-cause mortality and most cause-specific mortality, with a lower BMI associated with an increased risk of death33. However, to a significant extent, the dispute regarding the ‘obesity paradox’ can be elucidated by the circumstance that individuals with a relatively lower BMI range34 possess a lower lean body mass and body weight rather than a diminished quantity of body fat, so it was not significant according to LASSO regression.

Upon reviewing the literature, other indicators of obesity, such as WHtR and WWI, were included in this study. These newly proposed indicators explain certain diseases better than BMI25, so they were incorporated into the model. Although both WWI and WHtR were identified as meaningful predictors under the chosen regularization parameters in the LASSO regression, which aligns with previous research18, WWI was subsequently excluded from the nomogram model due to its lack of statistical significance in the logistic regression. This could be due to the different inclusion of other variables in the model or the varying circumstances of the sample.

Gender, age, ethnicity, and PIR were also selected as important factors in this model, which is also roughly the same as the results of Wang17 study, where gender and age were likewise included in the model as important factors, whereas different ethnicities were not included. This may be because although the samples in the previous study and this study are based on NHANES, they were collected before and after the outbreak of COVID-19, leading to different sample selection methods.

Diabetes and hypertension were included in this analysis. In addition, diabetes was included in the nomogram model as a significant parameter. However, this is roughly the same as the research results of Matsunaga et al.35 because there is a correlation between metabolic abnormalities and some types of inflammation; however, in some studies36, diabetes and arthritis may be complications, so further research is needed to address these contradictions. In logistic regression, hypertension was excluded, which is slightly different from the results of previous studies37. In their study, the hemodynamic abnormalities induced by primary hypertension38 may further promote the transformation of endothelial cells into a proinflammatory phenotype, increase the expression of inflammatory genes and adhesion molecules, and exacerbate the inflammatory cascade response. However, in this study, hypertension was a significant variable in arthritis according to LASSO regression but was not clearly associated with logistic regression; this may be due to the difference in samples. Thus, there is still a contradiction in this area, and further studies need to explore this association.

Vitamin D deficiency39 is associated with numerous health issues. For instance, rheumatoid arthritis, an autoimmune disease, is a chronic inflammatory systemic disorder that can damage joints, leading to cartilage destruction and bone erosion. Vitamin D3, acting as a steroid hormone40, plays a significant role in bone metabolism. Despite the absence of a consensus regarding human serum Vitamin D levels under both healthy and pathological conditions, concentrations ranging from approximately 30 to 100 ng/mL have been reported in healthy individuals, and concentrations ranging from 21 to 29 ng/mL characterise a VitD-deficient state. Levels less than 20 ng/mL indicate significant Vitamin D deficiency41. Therefore, in this study, serum vitamin D levels were analyzed in order of quartiles into 4 groups, with a high risk of arthritis at high concentration levels in the fourth group, which is considered paradoxical because there may be cases where arthritis patients have followed medication prescriptions and consumed vitamin D for a long time.

This result revealed that the SII can be used as a parameter in predictive models of arthritis. Consistent evidence from previous studies10 suggests that the SII is a more precise predictor of inflammation and may also be added as a parameter to future models for predicting inflammation-related diseases.

Among the nomogram predictors, WHtR contributes more to the prediction of results, which is similar to previous research42. In their study, the concept of the triglyceride glucose index was also introduced, but the effect of WHtR was not evaluated. This study improved upon this and found that WHtR has a significant impact on arthritis. Thus, high-risk groups can monitor changes in these variables, with WHtR being easily obtained by measuring waist circumference and height. Compared with BMI, WHtR has a better predictive effect on arthritis.

Study strengths and limitations

The study has several strengths. Firstly, it is the first to identify WHtR as a vital influencing factor for the risk of arthritis. Secondly, for the first time, SII and WHtR, along with other easily obtainable factors, were combined to construct a simple, feasible, fast, and cost-effective arthritis incidence prediction model. The model has been validated through a validation set to confirm its reliability, consistency, and accuracy.

This study also has several limitations. First, due to the nature of the cross-sectional study design, this study was unable to establish clear causal relationships. Second, the results of the current study are based on U.S. adults; therefore, it may not represent the characteristics of other populations. Third, although this study adjusted for a number of potential confounders, it was unable to completely rule out the possibility of unmeasured confounders. Additionally, the study could not develop more accurate models for predicting arthritis due to incomplete data for the years 2021–2023, such as TG, LDL, some laboratory data, and dietary data.

Despite these limitations, this study has developed a new nomogram model that performs well.

Conclusion

Through the above research, it can be concluded that SII and WHtR play an important role in the risk of arthritis. Therefore, this study systematically integrated the predictive role of key variables in arthritis and established a bar chart. Due to the low cost and easy collection of variables in this bar chart, in the future, it can save health resources, diversify the prediction of arthritis, and provide more effective methods for early prevention, control of disease progression, and avoidance of serious harm caused by arthritis. For example, high-risk populations can implement targeted interventions on high-risk variables through the bar chart of this study, such as reducing waist circumference through abdominal exercise to lower WHtR, or allowing doctors and nurses to pay more attention to SII or other easily obtainable indicators during physical examinations of high-risk populations to reduce the risk of arthritis.

Data availability

The summary statistical data used and/or analyzed in this study can be found at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.

References

Xue, Q. et al. Association between arthritis and depression risk: A prospective study and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord 273, 493–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.04.038 (2020).

Myasoedova, E., Davis, J. M., Crowson, C. S. & Gabriel, S. E. Epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis: rheumatoid arthritis and mortality. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 12(5), 379–385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-010-0117-y (2010).

Gu, Y. T. et al. Research progress on osteoarthritis treatment mechanisms. Biomed. Pharmacother. 93, 1246–1252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2017.07.034 (2017).

Zhang, X. et al. Association between different triglyceride-glucose index combinations with obesity indicators and arthritis: results from two nationally representative population-based study. Eur. J. Med. Res. 29(1), 389. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-024-01992-4 (2024).

Yin, K. J. et al. No genetic causal association between periodontitis and arthritis: A bidirectional two-sample mendelian randomization analysis. Front. Immunol. 13, 808832. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.808832 (2022).

Fan, W. et al. Analyzing the impact of heavy metal exposure on osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: An approach based on interpretable machine learning. Front. Nutr. 11, 1422617. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1422617 (2024).

Zhao, X. et al. Clinical, humanistic, and economic burden of osteoarthritis among noninstitutionalized adults in the united States. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 27(11), 1618–1626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2019.07.002 (2019).

Hawker, G. A. & King, L. K. The burden of osteoarthritis in older adults. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 38(2), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2021.11.005 (2022).

Palazzo, C., Nguyen, C., Lefevre-Colau, M. M., Rannou, F. & Poiraudeau, S. Risk factors and burden of osteoarthritis. Ann. Phys. Rehabil Med. 59(3), 134–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2016.01.006 (2016).

Liu, B., Wang, J., Li, Y. Y., Li, K. P. & Zhang, Q. The association between systemic immune-inflammation index and rheumatoid arthritis: Evidence from NHANES 1999–2018. Arthritis Res. Ther. 25(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-023-03018-6 (2023).

Jiang, Y. et al. New inflammatory marker associated with disease activity in gouty arthritis: The systemic inflammatory response index. J. Inflamm. Res. 16, 5565–5573. https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S432898 (2023).

Wu, D. et al. Association between handgrip strength and the systemic immune-inflammation index: A nationwide study, NHANES 2011–2014. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19(20), 13616. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013616 (2022).

Hou, K., Song, W., He, J. & Ma, Z. The association between non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (NHHR) and prevalence of periodontitis among US adults: a cross-sectional NHANES study. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 5558. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56276-y (2024).

Tan, M. Y. et al. The association between non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Recent findings from NHANES 2007–2018. Lipids Health Dis. 23 (1), 151. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-024-02143-8 (2024).

Yang, X. et al. Arthritis is associated with an increased risk of incident diabetes in Chinese adults: A nationwide cohort study and updated meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 38(2), e3487. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.3487 (2022).

Xie, C., Chen, Q. & Adipokines New therapeutic target for osteoarthritis? Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 21(12), 71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-019-0868-z (2019).

Wang, X., Guo, Z., Wang, M. & Xiang, C. Association between body roundness index and risk of osteoarthritis: A cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis. 23(1), 334. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-024-02324-5 (2024).

Wang, X., Xie, L. & Yang, S. Association between weight-adjusted-waist index and the prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis: A population-based study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 24(1), 595. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-023-06717-y (2023).

Cai, Y., Zhou, Z. & Zeng, Y. Association between non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (NHHR) and sleep disorders in US adults: NHANES 2005 to 2016. Med. (Baltim). 103(26), e38748. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000038748 (2024).

Ji, Y., Wei, C. B., Gu, W. & Hou, L. L. Relevance of vitamin D on NAFLD and liver fibrosis detected by vibration controlled transient elastography in US adults: A cross-sectional analysis of NHANES 2017–2018. Ann. Med. 55(1), 2209335. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2023.2209335 (2023).

Su, W. Y. et al. Metabolic syndrome and Obesity-Related indices are associated with rapid renal function decline in a large Taiwanese population follow-up study. Biomedicines 10(7), 1744. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10071744 (2022).

Khanna, D., Peltzer, C., Kahar, P. & Parmar, M. S. Body mass index (BMI): A screening tool analysis. Cureus 14(2), e22119. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.22119 (2022).

Ku, H. C., Cheng, E. & Cheng, C. F. A body shape index (ABSI) but not body mass index (BMI) is associated with prostate cancer-specific mortality: Evidence from the US NHANES database. Prostate 84(9), 797–806. https://doi.org/10.1002/pros.24698 (2024).

Zhang, A. et al. Conicity-index predicts all-cause mortality in Chinese older people: A 10-year community follow-up. BMC Geriatr. 22(1), 971. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03664-6 (2022).

Wu, J. & Guo, J. Is weight-adjusted waist index more strongly associated with diabetes than body mass index and waist circumference? Results from the database large community sample study. PLoS One 19(9), e0309150. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0309150 (2024).

Kelesoglu Dincer, A. B. & Sezer, S. Systemic immune inflammation index as a reliable disease activity marker in psoriatic arthritis. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 32(6), 773–778. https://doi.org/10.29271/jcpsp.2022.06.773 (2022).

Mao, Y. et al. Association between dietary inflammatory index and stroke in the US population: Evidence from NHANES 1999–2018. BMC Public. Health 24(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-17556-w (2024).

Ma, X. et al. Developing and validating a nomogram for cognitive impairment in the older people based on the NHANES. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1195570. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2023.1195570 (2023).

Li, R. et al. Establishment and evaluation of a novel practical tool for the diagnosis of pre-sarcopenia in young people with diabetes mellitus. J. Transl Med. 21(1), 393. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-04261-w (2023).

Yang, L. et al. Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting all-cause mortality in American adult hypertensive populations. Front. Pharmacol. 14, 1266870. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1266870 (2023).

Alissa, E. M., Alzughaibi, L. S. & Marzouki, Z. M. Dietary intake of fatty acids and antioxidants in relation to radiographic knee osteoarthritis: Results from a case-control study. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 33(3), 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12712 (2020).

Yang, Y. et al. Trajectory of mid-arm subcutaneous fat, muscle mass predicts mortality in Hemodialysis patients independent of body mass index. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 14005. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64728-8 (2024).

Bhaskaran, K., Dos-Santos-Silva, I., Leon, D. A., Douglas, I. J. & Smeeth, L. Association of BMI with overall and cause-specific mortality: A population-based cohort study of 3·6 million adults in the UK. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 6 (12), 944–953. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30288-2 (2018).

Lee, D. H. et al. Predicted lean body mass, fat mass, and all cause and cause specific mortality in men: Prospective US cohort study. BMJ 362, k2575. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2575 (2018).

Matsunaga, M., Lim, E., Davis, J. & Chen, J. J. Dietary quality associated with self-reported diabetes, osteoarthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis among younger and older US adults: A cross-sectional study using NHANES 2011–2016. Nutrients 13 (2), 545. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020545 (2021).

Dong, Q., Liu, H., Yang, D. & Zhang, Y. Diabetes mellitus and arthritis: is it a risk factor or comorbidity? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med. (Baltim). 96(18), e6627. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000006627 (2017).

Liang, X., Chou, O. H. I., Cheung, C. L. & Cheung, B. M. Y. Is hypertension associated with arthritis? The United States National health and nutrition examination survey 1999–2018. Ann. Med. 54(1), 1767–1775. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2022.2089911 (2022).

Dai, G. et al. Distinct endothelial phenotypes evoked by arterial waveforms derived from atherosclerosis-susceptible and -resistant regions of human vasculature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 101(41), 14871–14876. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0406073101 (2004).

Harrison, S. R. et al. Autoimmune disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Calcif Tissue Int. 106(1), 58–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-019-00577-2 (2020).

Adorini, L. & Penna, G. Dendritic cell tolerogenicity: A key mechanism in immunomodulation by vitamin D receptor agonists. Hum. Immunol. 70(5), 345–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humimm.2009.01.016 (2009).

Holick, M. F. et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 96(7), 1911–1930. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2011-0385 (2011).

Dang, K. et al. The association between triglyceride-glucose index and its combination with obesity indicators and cardiovascular disease: NHANES 2003–2018. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-02115-9 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the study participants and research staff for their contributions and commitment to this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Y. and F.-Y.X.: conceived the study, designed the study protocol, and drafted the manuscript. W.-B.G., H.X., K.H., and W.-S.K.: the samples and performed the analyzed interpretation of the data. H.X., K.H., and W.-S.K.: critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, Y., Feng, Y., Wu, S. et al. Development and validation of a nomogram for arthritis: a cross-sectional study based on the NHANES. Sci Rep 15, 7248 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92014-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92014-8