Abstract

As an image enhancement technology, multi-modal image fusion primarily aims to retain salient information from multi-source image pairs in a single image, generating imaging information that contains complementary features and can facilitate downstream visual tasks. However, dual-stream methods with convolutional neural networks (CNNs) as backbone networks predominantly have limited receptive fields, whereas methods with Transformers are time-consuming, and both lack the exploration of cross-domain information. This study proposes an innovative image fusion model designed for multi-modal images, encompassing pairs of infrared and visible images and multi-source medical images. Our model leverages the strengths of both Transformers and CNNs to model various feature types effectively, addressing both short- and long-range learning as well as the extraction of low- and high-frequency features. First, our shared encoder is constructed based on Transformers for long-range learning, including an intra-modal feature extraction block, an inter-modal feature extraction block, and a novel feature alignment block that handles slight misalignments. Our private encoder for extracting low- and high-frequency features employs a dual-stream architecture based on CNNs, which includes a dual-domain selection mechanism and an invertible neural network. Second, we develop a cross-attention-based Swin Transformer block to explore cross-domain information. In particular, we introduce a weight transformation that is embedded into the Transformer block to enhance the efficiency. Third, a unified loss function incorporating a dynamic weighting factor is formulated to capture the inherent commonalities of multi-modal images. A comprehensive qualitative and quantitative analysis of image fusion and object detection experimental results demonstrates that the proposed method effectively preserves thermal targets and background texture details, surpassing state-of-the-art alternatives in terms of achieving high-quality image fusion and improving the performance in subsequent visual tasks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Image fusion enhances the image quality by extracting and combining the most relevant information from various source images, resulting in a single image that is more robust and informative, which is advantageous for subsequent applications. This area has become a significant research focus in image processing. Image fusion techniques can be classified into digital photography image fusion, multi-modal image fusion (MMIF), and sharpening fusion according to specific fusion scenarios. Infrared and visible image fusion (IVF) and medical image fusion (MIF) are two challenging sub-categories of multi-modal image tasks1. The advancement of MMIF technology for multi-task scenarios is primarily driven by the significant differences in the information captured by various devices. In IVF, infrared and visible images are acquired by infrared and optical sensors, respectively, which capture the thermal radiation and spectral information of the scene. Infrared images are particularly sensitive to objects and regions with distinct infrared thermal characteristics that are imperceptible to human vision, particularly under challenging conditions such as nighttime or fog. In contrast, visible images present objects with visible reflective characteristics, encompassing a wealth of edges and details, thereby providing information that aligns with human visual perception. In MIF, source images are generated through interactions between the human body and various media, such as X-rays, electromagnetic fields, and ultrasound2. Depending on the salient information of the source images, they can be classified into structural images that emphasize spatial texture and functional images that emphasize intensity distribution. Structural images mainly include Computed Tomography (CT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), whereas functional images primarily include Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT)3. The combination of multi-source images results in accurate scenes and reliable complementary descriptions. Many methods have been developed to address the challenges of MMIF in recent years. MMIF technology serves as a low-level vision task for high-level vision tasks such as object detection4, pedestrian recognition5, semantic segmentation6, and scene perception7, making it widely applicable in military surveillance, medical imaging8, industry9, and other practical applications.

The imaging principles of different sensors are diverse, leading to distinct emphases in the scene description of the multi-modal images that they capture. Existing image fusion methods can be categorized into traditional image fusion techniques that are implemented earlier and deep learning-based image fusion methods. Traditional image fusion techniques typically adopt relevant mathematical logic, including multi-scale transform, sparse representation, subspace, and saliency-based theory. Subsequently, the activity levels are manually analyzed in either the spatial or transform domain to design the fusion rules. With the in-depth research on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and Transformers, researchers have applied deep learning to image fusion, leading to the development of methods based on CNNs, auto-encoders (AEs), generative adversarial networks (GANs), and Transformers. AE-based methods are widely used for learning hierarchical representations. The encoder is responsible for feature extraction, followed by the fusion of feature maps via designed algorithms such as weighted averaging, and finally, the decoder reconstructs the results. CNN-based methods focus on designing sophisticated integrated network architectures and the corresponding loss functions to achieve feature extraction, feature fusion, and image reconstruction. GAN-based methods generate fusion results through adversarial games between the discriminator and generator so that the generated fusion results converge with the target distribution in terms of the probability distribution, thereby implicitly achieving feature extraction, fusion, and reconstruction. Transformer-based methods introduce self-attention mechanisms by inductively capturing human visual perception patterns, allowing for adaptive weighted fusion of features from regions that are of greater interest to human vision.

Since the introduction of DDPM (Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models)10 to the public in 2020, more researchers have started to apply diffusion models to computer vision (CV) tasks such as low-light enhancement11,12, super-resolution13, semantic segmentation14, shadow removal15, and image fusion16,17,18. Compared with deep-learning-based methods, traditional frameworks typically aggregate complementary information in the spatial or transform domain. However, they cannot exchange information between non-adjacent pixels19, which leads to insufficient consideration of the inherent differences in features across different modalities. In addition, their approximate manual measurements and increasingly complex requirements limit the development of related practical applications.

CNN-based modules have long served as backbone networks for CV tasks. They operate based on the guidelines of local processing, using uniform convolutional kernels to extract features within the perceptive field. The entire process has a limited receptive field and does not consider the global context effectively. In contrast, Transformer, which has been introduced for low-level vision tasks, utilizes attention mechanisms to model long-range dependencies and provides promising performance. Nevertheless, several issues still need to be addressed in image fusion tasks that process multi-source images. First, Transformer-based fusion models generally have many parameters, which limits their applicability to devices with limited memory. Second, although the standard Transformer and its variants possess self-attention mechanisms with global context perception, they lack the ability to explore cross-domain information among source images from different devices, which affects the integration of complements between them. Therefore, we fully consider the strengths and weaknesses of CNN and Transformer classes to design a comprehensive fusion network. Another important issue is the careful selection of the overall architecture of the fusion network. At present, common and effective fusion network architectures include residual connections20,21, dense connections22,23, and dual-stream architectures8,24. The dual-stream architecture efficiently extracts features from different modalities, and offers better adaptability to the unified fusion of multi-modal source images involving multiple fields.

We develop a dual-branch AE-based framework for MMIF based on a combination of CNN and Transformer to prompt models to focus on the above mentioned challenges. First, we combine the global self-attention mechanism and long-range dependency modelling of Transformer with the local perspective and computational efficiency of the CNN. We use Transformer-based blocks for intra- and inter-modal feature extraction to construct the shared encoder, while CNN-based blocks are used to build the private encoder. We introduce the Swin Transformer with weight transformation for efficient and low-complexity integration of intra- and inter-modal features, ensuring the quality of inter-modal interactions through an alignment block. The inter-modal feature extraction is guided by cross-attention. In addition, the private encoder employs a dual-stream architecture to refine the feature types better. We further introduce the dual-domain selection mechanism (DSM) and invertible neural networks (INN) for the targeted extraction of high- and low-frequency features. Second, multi-modal scene modelling is designed based on a unified standard that serves as the objective function for two-stage network learning, consisting of structure maintenance, texture preservation, and intensity control. The structure maintenance utilizes the structural similarity index measure (SSIM) loss with a dynamic weighting factor (DWF). The proposed model can be generalized to the field of MIF in MMIF, fusing different modalities of medical images (e.g., PET-MRI and SPECT-MRI) to provide informative and complementary fused images for clinical diagnosis.

The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

-

We propose an image fusion model for multi-modal images, including pairs of infrared and visible images and medical image pairs. Our model integrates the advantages of Transformer and CNN, considering different feature types, reducing the model complexity, and formulating a unified loss function with DWF tailored to the inherent commonalities of multi-modal images.

-

We introduce weight transformation to enhance the efficiency of the Transformer blocks in the model. In addition, we create a cross-attention-based Swin Transformer block with weight transformation.

-

Our shared encoder incorporates a feature alignment block for slight misalignment, and the private encoder is a dual-stream architecture composed of the DSM and INN.

-

The proposed method achieves superior performance in both low- and high-level visual tasks.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section Related work outlines related work on MMIF. Section Method introduces the proposed method. Section Experiments validates the proposed model in terms of both qualitative visual effects and quantitative evaluation metrics, along with a description of ablation experiments and an efficiency analysis. Section Conclusion summarises the study.

Related work

In this section, we review the current state of research on deep-learning-based MMIF and introduce the development of Transformers for visual tasks.

Deep-learning-based multi-model image fusion

Deep-learning-based methods learn optimal network parameters under the guidance of well-designed loss functions and achieve adaptive feature fusion, which has become the mainstream approach for image fusion tasks. AE-based methods are not demanding for the training dataset and generate relatively stable results. The representation contained in the fused image from the two source images is more balanced than that of other methods. Densefuse25 includes convolutional layers, a fusion layer, and dense blocks in the encoder for IVF, with the output of each layer affecting the feature map extraction. AUIF24 achieves dual-scale decomposition of infrared and visible images through a dual-stream architecture based on algorithm unrolling logic formulation. CDDFuse8 constructs a dual-stream encoder and decoder using Restormer, Lite Transformer, and INN blocks to perform MMIF tasks. GAN-based and end-to-end methods are prone to instability and rugged to converge during the training process. To alleviate the challenge of unbalanced fusion, GANMcC26 consists of an end-to-end GAN model with multi-classification constraints for IVF. The DDcGAN generator27 employs dense connections using trainable deconvolution layers for the generator input, while adding constraints to the downsampling process. The discriminator input is the image itself, rather than its gradient.

The selection of the network architecture is determined by the ideas and prior assumptions of researchers for solving MMIF tasks. Approaches using the dual-stream architecture presume that the source images from each modality should be considered for low-frequency foreground targets and high-frequency background details, rather than simply extracting base features from infrared images and texture features from visible images28. In addition to CDDFuse and AUIF, CNN-based PSTLFusion29 and MDLatLRR30 also select the dual-stream architecture. PSTLFusion introduces omnidirectional spatially variant recurrent neural networks to construct a fusion network for parallel scenes and texture learning. MDLatLRR consists of an IVF method based on latent low-rank representation, which decomposes source images into base parts and salient features and then uses the nuclear norm and an averaging strategy for feature fusion. In addition, some methods utilize the Nest connection architecture, such as NestFuse22 and Rfn-Nest23. This architecture inevitably encompasses the convolutional layers from large-scale networks. During training and testing, models with the Nest connection architecture generate a plethora of multi-channel feature maps and corresponding filter kernels. Consequently, additional computer memory is required for storage and computation. In contrast, the dual-stream architecture is more straightforward, exhibits stronger adaptability to various feature extraction and fusion algorithms, and has a wider range of applications.

MMIF focuses on modelling cross-modal features from different sensors and integrating them into an output image. General image fusion methods for multi-modal images require more robust feature integration and generalization capabilities than those that are designed explicitly for IVF or MIF. IFCNN31 is an end-to-end fully convolutional network that relies on large-scale datasets to train the network parameters. With an adaptive decision block managing the gradient term and adjusting the weight of the intensity loss term, SDNet32 formulates the MMIF problem as the extraction and reconstruction of gradients and intensities. RFNet33 consists of an MMIF network in which registration and fusion are the mutually reinforcing, first optimizing the registration performance from coarse to fine and then adopting a gradient channel attention mechanism to preserve the texture. U2Fusion34 is an unsupervised end-to-end network developed to address the problems of training storage, computational efficiency, and catastrophic forgetting in general image fusion models.

Transformer in vision tasks

Transformer, which is a neural network model based on the self-attention mechanism, was first proposed by Vawani et al. for machine translation. Subsequently, Dosovitskiy et al.35 adapted Transformer for the CV field and proposed the Vision Transformer (ViT). Liu et al.36 innovated the Hierarchical ViT using Shifted Windows (Swin Transformer), addressing issues such as the high complexity and low feature map resolution of ViT, and attempted to replace CNNs with Transformers as a general-purpose backbone for CV. Transformers have rapidly advanced in the CV field owing to their remarkable performance and have been applied to solve various visual tasks, including image fusion. IFT37 leverages Transformer to provide a spatio-Transformer fusion strategy for feature integration. SwinFusion19 includes intra- and cross-domain fusion blocks based on the Swin Transformer to integrate long-range cross-domain features better, summarizing multi-scene fusion challenges into structure maintenance, detail preservation, and proper intensity control to yield a general image fusion model. SwinFuse38 consists of a pure Transformer network based on the residual Swin Transformer, with deep learning responsible for training the network parameters for feature extraction and reconstruction, whereas feature fusion is achieved using the \({l_1}\)-norm for sequence matrices. Transformer in STFNet39 is utilized to capture detail information and context relationships across different modalities. STFNet additionally incorporates a feature alignment network to align slightly misaligned images. DATFuse21 designs a dual-attention residual module to extract essential features and a Transformer module to preserve complementary information further, thereby maintaining long-range complementary information.

ViT parameters consume a significant amount of storage space and memory, rendering ViT-based modelling unsuitable for applications with limited computational resources or those requiring real-time inference. Researchers have proposed various strategies to address this issue, including sliding windows, linear attention, knowledge distillation40, and weight sharing41. MiniViT40 uses weight multiplexing as the central technique for designing a weight transformation and weight distillation based on the concepts of cross-layer weight sharing and knowledge distillation. This approach enables parameter compression without sacrificing accuracy, and experimental results on large datasets have demonstrated excellent performance. TinyViT42 primarily solves the problem of saturation or underfitting that arises when transferring large Transformer models trained on extensive datasets to smaller models. TinyViT introduces fast knowledge distillation that focuses more on the distillation in the pre-training phase than in the fine-tuning phase. FLatten Transformer43 includes focused linear attention to address the performance degradation and additional computational overhead associated with blindly replacing self-attention with linear attention. The focused linear attention block includes a mapping function to concentrate the attention weights and a rank restoration module to ensure that the output features are diversified. Compared with global self-attention, focused linear attention is more efficient for processing large-scale images with a smaller memory footprint and less time complexity.

The central technique of MiniViT is weight multiplexing, which consists of weight transformation and weight distillation. Weight distillation adopts the concept of knowledge distillation, inheriting the optimal parameters obtained from the training of a larger model to enhance the performance of the student model, while also improving its adaptability to different tasks and datasets. The features of each layer differ after normalization, and weight transformation ensures the diversity and non-linearity of the shared parameters to prevent training collapse. TinyViT includes a fast pre-training distillation framework to solve the problem of transferring the power of large-scale pre-trained data to smaller models while reducing the number of parameters.

Method

In this section, the proposed MMIF framework is comprehensively described. First, we present the overall framework. Next, we focus on the Swin Transformer with weight transformation technology and the detailed network architecture. Finally, the design of the loss function that incorporates a DWF is presented.

Overall framework

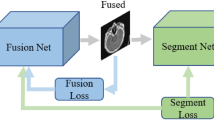

The overall framework is shown in Fig. 1. We design a feature extraction network with a dual-stream structure instead of relying solely on the complex blind learning of Transformer to extract the required features. The main path of the dual-stream structure includes a shared encoder, private encoder, and decoder. The training employs a two-stage strategy coupled with a redesigned loss function based on structure maintenance, texture preservation, and intensity control rules to improve the quality of the fused images and enhance the feature retention.

The Transformer-based shared encoder effectively constructs long-range dependencies. However, it is limited to intra-modal contextual information and fails to integrate cross-modal contextual information, which is crucial for MMIF tasks with multiple source images. Inspired by SwinFusion, our shared encoder incorporates an inter-modal feature extraction block (inter-FEB) in addition to an intra-modal feature extraction block (intra-FEB). Another critical factor for the fusion results is the registration alignment. To process images that are acquired from an aligned device, it is typically assumed that the source images are strictly aligned. Indeed, measurement errors from the devices lead to several slightly misaligned image pairs in the dataset, as shown in Fig. 2. These flawed image pairs undoubtedly introduce artifacts into the results through image fusion networks, thereby affecting the fusion quality. Therefore, we introduce a feature alignment block (FAB)39 before the inter-modal interaction to avoid this problem. In addition, the dual-stream architecture requires the separate design of appropriate networks for high- and low-frequency features. To emphasize the response of important regions, we select the DSM44 to extract texture details, whereas the INN8 is responsible for the base structures.

The CNN-based private encoder provides separate base and detail extractors for the features of the two modalities to accommodate source images from various fields as input.

Weight transformation

Research on image fusion should focus on the task itself, rather than blindly considering the superfluity of the scale of neural networks and the number of model parameters. The standard Transformer is designed to capture the long-range self-similarity dependency among all tokens in a single image. Because the shared encoder needs to learn global information as comprehensively as possible and integrate complementary information between two modalities, more information is required to apply the standard Transformer structure directly for MMIF. We use the weight transformation of weight multiplexing from MiniViT to create our Swin Transformer-based encoder that contains intra- and inter-modal interactive feature extraction. We establish a cross-domain multi-head self-attention mechanism for shared feature extraction, while retaining the intrinsic features of different modalities.

Weight multiplexing is a technology that is used to compress ViT, reducing the number of model parameters while striving to maintain model performance. In particular, it reduces the total parameter count by sharing weights across multiple layers. However, simple weight sharing results in training instability and performance degradation. Therefore, weight management strategies are required to optimize the performance and efficiency of ViT. Weight transformation ensures the diversity of shared weights through linear or other forms of transformation, allowing the shared weights to adapt to different layers.

Weight transformation is imposed on both the Swin Transformer block and cross-attention-based Swin Transformer block of our model. The inputs to the cross-attention are two different sequences with the same dimensions, that is, different modalities in this study. They provide the Key and Value to one another and combine the Query of their own features to compute the attention matrix in a cross-manner. Figure 3 showns an example plot of the cross-attention-based Swin Transformer with the weight transformation block. Transform1 in Fig. 3 refers to the linear transformation applied before and after the softmax module of the multi-head self-attention modules with regular/shifted windowing configurations (W-/SW-MSA). Transform2 is employed before the MLP, with specific steps including (1) adjusting the vector dimensions followed by convolution processing and (2) reverting the dimensions back to their original state.

Network architecture

The effective integration of input images is of great significance for enhancing the image quality and information availability In MMIF. In the proposed network, the Swin Transformer-based blocks are all combined with weight transformation to optimize the spatial complexity.

Shared encoder, including the intra-FEB, inter-FEB, and FAB, is used to encode the common features of multi-modal inputs. The intra-FEB extracts fine-grained features from the inputs productively, and the inter-FEB employs a cross-attention mechanism to enhance the feature correlation, which can be formulated as:

where \({I_1} \in {{\mathbb {R}}^{H \times W \times {C_{in}}}}\) and \({I_2} \in {{\mathbb {R}}^{H \times W \times {C_{in}}}}\) are from different modalities. \({S_A}( \cdot )\) denotes the intra-FEB of the shared encoder, which consists of two \(3 \times 3\) convolutional layers and the Swin Transformer with weight transformation of depth 2. \({S_E}( \cdot )\) represents the inter-FEB configured as a cross-attention-based inter-model fusion block. \({F_A}\) and \({F_E}\) denote the feature maps extracted after intra-FEB and those feature maps acquired after inter-FEB in addition to intra-FEB, respectively.

To avoid the adverse effects of slightly misaligned source images on network learning and achieve feature alignment, we establish the FAB \(A( \cdot )\) based on deformable convolution between the intra-FEB and inter-FEB. Whereas normal \(3\times 3\) convolution kernels are geometrically fixed and can only compute features for a limited range of neighboring pixel points, deformable convolution allows the convolution kernel to be spatially deformed to accommodate geometric changes in the feature map. Thus, deformable convolution can add displacement to the normally sampled coordinates to obtain a new feature map following alignment. Specifically, the features extracted by the intra-FEB are cascaded, and a series of offsets for \(F_A^2\) in the X- and Y-axis directions are obtained using multiple convolutions against \(F_A^1\). Finally, this offset is used to construct a deformable convolution45 to achieve alignment with \(F_A^1\). Therefore, Eq. 2 for the shared encoder is expressed as follows, where \({\hat{F}}_A^2\) is the feature map after alignment with \(F_A^1\).

Private encoder further considers the separate extraction and processing for high- and low-frequency features on the basis of common features \(F_E^1\) and \(F_E^2\). As shown in Fig. 1c, the DSM utilizes the complementary characteristics of the spatial and frequency domains, dynamically selecting and emphasizing spatial and frequency domain features according to different modalities. These features are used in the subsequent reconstruction process. The spatial domain processes pixel information, better handling details and edges, whereas the frequency domain focuses on frequency components and performs well in removing unnecessary noise and recovering from blurriness. Therefore, the DSM is selected for background detail features and the INN is selected for foreground target features. Unlike pure convolutional layers, the INN ensures lossless feature information transmission; the calculation details are shown in Fig. 1e. The inputs of our INN block are \({F_0}[1:c]\) and \({F_0}[c + 1:C]\), which represent the 1st to cth channels and \(c+1\)th to Cth channels of the input feature \({F_0} \in {\mathbb{R}^{H \times W \times C}}\), respectively. In each invertible layer, the transformation is:

where \(\textrm{A}( \cdot )\), \(\textrm{N}( \cdot )\), and \(\textrm{B}( \cdot )\) are the mapping functions from the bottleneck residual block (BRB) in MobileNetV246, denoting a linear transformation, non-linear per-channel transformation, and linear transformation, respectively.

The complete procedure of the private encoder can be represented as:

where \({P_B}( \cdot )\) and \({P_D}( \cdot )\) are the high- and low-frequency feature processors, that is, the INN and DSM, respectively. \({F_B}\) and \({F_D}\) denote the base features and detail features, respectively, obtained by the two feature processors.

Decoder \(D( \cdot )\) consists of two layers of Swin Transformer and three \(3\times 3\) CNNs. In Training Stage I, the formula for generating and reconstructing \({{{\hat{I}}}_1}\) and \({{{\hat{I}}}_2}\) is as follows:

The purpose of Training Stage II is to generate a fused image \({I_f}\). Because feature fusion involves cross-modal and multi-frequency features, the decoder merges the fused base and detail features processed by the DSM and INN, respectively, which can be written as:

where \(F{P_B}( \cdot )\) and \(F{P_D}( \cdot )\) represent the base fusion processor and detail fusion processor, respectively.

Loss function

Because of the lack of ground truth in MMIF tasks, Training Stage I obtains the optimal network parameters for feature extraction and reconstruction by constraining the similarity between the reconstructed and source images. On this basis, Training Stage II introduces the fusion block and constrains the network learning through proper structure maintenance, texture preservation, and intensity control.

where \(\lambda\), \({\lambda _1}\), \({\lambda _2}\), \({\lambda _3}\), and \({\lambda _4}\) are tuning parameters. Structure maintenance, texture preservation, and intensity control correspond to loss parts \(L_{ssim}^{II}\), \(L_{text}^{II}\) and \(L_{int}^{II}\), which are denoted as:

where \(ssim( \cdot )\) denotes the structural similarity operation, \(\nabla\) is the gradient operation, and \(\max ( \cdot )\) is the maximum operation. H and W are the height and width of the image, respectively.

\({w_1}\) and \({w_2}\) control the degree of structural preservation for two inputs, and are often set to 0.5 or another fixed value. We expect the loss function to be automatically adjusted according to the feature representation ability of the source images; therefore, we propose the DWF. The DWF measures the edges and details through gradient values calculated by the Laplacian operator \(\Delta\), and determines \({w_1}\) and \({w_2}\) based on the feature measurement. A higher weight indicates a higher degree of corresponding information preservation, which is described as:

Experiments

In this section, we elaborate on the datasets, implementation details, comparison methods, and evaluation metrics used in the experiments. Subsequently, to demonstrate the superiority of our method, we compare 12 approaches from both qualitative and quantitative perspectives. The comparison includes image fusion and high-level visual tasks. Furthermore, ablation studies and efficiency analyses are presented to verify the rationality of each module.

Experimental configurations and implementation details

Datasets and implementation details

The proposed approach is implemented and trained on an NVIDIA TITAN RTX GPU and Intel(R) Xeon(R) E5-2678 v3 CPU @2.50 GHz with the PyTorch framework. We train the proposed model on the M3FD dataset for IVF tasks, which consists of high-resolution image pairs of size \(1024\times 768\). We select 2,700 image pairs collected from urban road scenes from this dataset as our training set. The dataset includes common objects found in surveillance and autonomous driving applications, such as Person, Car, Bus, Motorcycle, Lamp, and Truck. It can also be further utilized to evaluate high-level CV tasks such as object detection. In addition to the M3FD dataset, we comprehensively validate the fusion performance of our model on the FMB and RoadScene datasets. The FMB dataset includes 1,500 image pairs with a resolution of \(800\times 600\). The RoadScene dataset comprises 221 pairs of infrared and visible images depicting scenes involving roads, vehicles, and pedestrians. The test dataset comprises 200 randomly selected images from the M3FD dataset, 20 images from the RoadScene dataset, and 100 images from the FWB dataset.

These datasets include both daytime and nighttime scenarios to simulate various challenges in real-world applications, thereby enhancing the persuasiveness of the experiments. The parameters of the fusion network are empirically set as \(\lambda = {\lambda _1} = {\lambda _3} = 5\) and \({\lambda _2} = {\lambda _4} = 10\) to balance the difference in the order of magnitude between several components. The batch size is set to 12, and the number of training steps is set to 20000. The initialization learning rate of the Adam optimizer for the parameters is set to 2e-5, and then decayed exponentially.

Similarly, to train our medical imaging models, we utilize the publicly available Harvard Medical Dataset, which includes both normal and pathological brain images. We select 249 images for training the PET-MRI model and 337 images for training the SPECT-MRI model. Each test dataset comprises 20 images from the respective datasets.

Comparison methods and evaluation metrics

To evaluate the fusion effect of IVF, we compare our model with nine advanced methods: IFCNN31, U2Fusion34, SeAFusion7, SwinFusion19, SuperFusion47, TarDAl4, SDDGAN48, CoCoNet49, and Diff-IF50. IFCNN, U2Fusion, SwinFusion, and CoCoNet are general MMIF models. For MIF, we conduct the following comparison methods: CSMCA51, IFCNN, U2Fusion, EMFusion52, DSAGAN53, SwinFusion, and CoCoNet. The codes for the above comparison methods are publicly available, and the parameter settings are the default values specified in the corresponding papers.

We select five evaluation metrics for the quantitative comparison of the quality of the fused images to demonstrate the effectiveness of our fusion method: mutual information (MI)54, spatial frequency (SF)55, visual information fidelity (VIF)56, gradient-based fusion performance (\(Q^{AB/F}\))57, and structural similarity index measure (SSIM)58. MI is a metric based on information theory that assesses the transformation between source images by indicating the mutual dependence among diverse distributions. SF, which reflects details such as edges and textures by measuring the gradient of the fused image, is based on the image features. VIF quantifies the amount of information shared between the output and inputs based on natural scene statistics and the human visual system. \(Q^{AB/F}\) computes the edge information transferred from the source images to the fused image. SSIM captures image distortion by evaluating the brightness, contrast, and structural elements.

Results and analysis of IVF

Qualitative comparison

In the visual comparison, we selected two images each from the nighttime and daytime scenes of the M3FD test dataset to demonstrate the superiority of our results, as shown in Fig. 4. To analyze the capability of the fusion method to extract information regarding foreground objects and background details while avoiding redundancy comprehensively, the object parts are highlighted with green boxes, and the detail areas are emphasized and enlarged with red boxes. Our method performs better in highlighting objects, preserving color, and maintaining the naturalness of the fused results. In particular, no color distortion occurred, as observed in images 00670(c) and 01728(c); there are no severe artifacts, as shown in images 00619(j) and 00719(h); detail loss is not present, as noted in images 00619(g)(k), 00670(i), and 01728(d)(i)(j); and there is no overexposure, as illustrated in images 00719(e)(f) and 01728(e)(f). Overall, IFCNN fails to preserve the original color information and artifacts are present at the edges of TarDAL scenes. SDDGAN suffers from excessive smoothing, resulting in insufficient prominence of visible components, which leads to poor detection. CoCoNet has image distortion and fails to highlight these targets.

To validate the generalization capabilities of the models, we apply the trained model to the FMB and RoadScene datasets, as shown in Fig. 5. In 00167, only our result is able to balance contrast and fully preserve useful information; in 00208, only our fusion result minimizes overexposure and smoothing; and in 193, ours ensures scene naturalness and preserves the details of the trunk and vehicle. Besides ours, TarDAL and CoCoNet also allow for differentiation of the trunk and vehicle, but they have unnatural sky regions. In 243, the zoomed-in area of CoCoNet is as clear as ours, yet the results of CoCoNet are dim visually.

Quantitative comparison

Following the intuitive visual comparison, we establish more precise metrics to compare the fusion effects of the various methods experimentally, as listed in Table 1. For the M3FD dataset, the proposed method achieves the best values for three metrics (i.e. MI, VIF, and \(Q^{AB/F}\)) and a suboptimal value for one metric (i.e. SSIM). This indicates that our results perform better in contrast, visual effects, and fidelity in terms of structure and edge texture.

Table 1 also lists the measurements on the FMB and RoadScene datasets, where higher values for the five metrics indicate better image quality. The similarly excellent data performance to that on M3FD further proves the wide and stable applicability of the proposed model.

Results and analysis of MIF

Qualitative comparison

Our work focuses on developing a unified model for MMIF, and we present a comparison on medical images, as shown in Figs. 6 and 7. In MRI and PET, MRI provides structural information while PET supplies functional information; in MRI and SPECT, SPECT provides functional information. Fusion models must to retain and reasonably integrate information from both modalities. Six sets of experimental results are presented. Benefiting from the inter-modal feature interaction and targeted extraction of both high- and low-frequency information, the proposed method effectively preserves high-value information and enhances color recovery. In the six visualizations, it is evident that our results achieve optimal reconstruction and visualization of the structure, details, and color. IFCNN and DSGAN exhibit severe color distortion. U2Fusion and CoCoNet fail to retain sufficient detail information. SwinFusion suffers from obscured MRI details. CSMCA and EMFusion do not preserve the edges as effectively as our method.

Quantitative comparison

In the MRI-PET and MRI-SPECT experiments, as shown in Table 2, it is clear that ours ranks highly in four metrics: MI, VIF, \(Q^{AB/F}\), and SSIM. Although IFCNN and CoCoNet have higher SF values, implying better gradient distribution, this also results in brighter functional and darker structural regions. Such an unreasonable operation leads to color distortion and the loss of structural details. In terms of edge intensity and direction, the best \(Q^{AB/F}\) value serves as evidence of the effectiveness of our fusion method.

Object detection evaluation

We conduct object detection experiments as supplementary assessments to evaluate the image understanding capabilities of all models. The experiments utilize the popular YOLOv7 model to test the detection performance and the mean Average Precision (mAP) from the Intersection over Union (IoU) 0.5 to 0.95 is calculated for the detection results of Person, Car, Bus, Motorcycle, Lamp, and Truck compared with the ground truth labels.

A visual comparison of the detection is shown in Fig. 8. It is evident that we can more comprehensively identify People, Car, and Truck with high confidence. In 00226, SeAFusion, SwinFusion, CoCoNet, and Diff-IF fail to recognize Person owing to poor contrast; in 00484, only our method can fully and correctly identify Car; and in 03603, IFCNN, SeAFusion, SwinFusion, and Diff-IF incorrectly identify Truck as Car, while CoCoNet misidentify the dustbin as Car. The quantitative comparison of the object detection is shown in Table 3. The mean value of our model is the best, and we can effectively detect complementary object information better than the other methods, i.e. Car, Motorcycle, Lamp, and Truck.

The above experiments demonstrate that our fusion method can preserve compelling features and is conducive to improving downstream object detection tasks.

Ablation experiments and efficiency analysis

Study on weight transformation

The weight transformation technique applied to the Transformer blocks is used to mitigate the issue of excessive parameter counts while maintaining the performance. As shown in Table 4, the model without weight transformation exhibits a larger model size and longer runtime.

Study on Feature Alignment Block (FAB)

Owing to the expensive equipment required to capture strictly aligned images and the disadvantages of registration methods, numerous slightly misaligned image pairs exist in datasets. Therefore, the FAB is more suitable for this situation. To verify the effectiveness of the FAB, we compare the performance of our model with and without the FAB. The image quality metrics, object detection accuracy, and model complexity are listed in Table 4. The presence of a slight misalignment affects the feature extraction and fusion, thereby reducing the image quality and detection accuracy. The FAB does not significantly increase the model complexity while aligning the feature maps.

Study on inter-modal Feature Extraction Block (inter-FEB)

The inter-FEB is composed of cross-attention-based Swin Transformer blocks, which can effectively aggregate long-range dependencies and contextual interactions between modalities. Without the inter-FEB, the model fails to represent the complementary intensity of the source image pairs sufficiently, thereby affecting the subsequent high-level CV tasks.

Study on Dynamic Weighting Factor (DWF)

The weight coefficients can change adaptively based on the amount of information contained in image pairs, and a better objective function can assist the network in learning the optimal parameters. This is reflected in the excellent image quality and object detection metrics listed in Table 4.

We present the model sizes of all methods and the average processing times during the inference phase on the M3FD dataset in Table 5. The diffusion model-based method has the largest size and a longer time. Owing to the presence of Transformer blocks in our model, it has a larger number of parameters and a longer inference time than pure CNN models. However, we design the joint CNN-Transformer framework by considering the respective advantages of Transformers and CNNs and optimize the drawbacks associated with Transformers. This is evident when compared with SwinFusion, which also employs a joint model. Our method takes the least time-consuming among the Transformer-based comparison methods.

Conclusion

In this paper, we propose a novel joint CNN-Transformer framework for MMIF tasks. This framework is composed of intra- and inter-modal interaction modules, along with a dual-stream architecture designed for diverse feature extraction. The modules based on Swin Transformer in our model are enhanced through weight transformation, and the dual-stream architecture is managed by the DSM and INN. Our model design effectively integrates the advantages of CNNs and Transformers, fully considering the modelling of short- and long-range dependencies as well as the extraction of low- and high-frequency features. A unified loss function incorporating the DWF is employed to guide the optimization of the network learning parameters. We train our models on the M3FD and Harvard Medical datasets. Our experiments encompass both image fusion and extended target detection, with qualitative and quantitative evaluations. The proposed method consistently exhibit superior performance in image quality metrics such as the MI, SF, VIF, \(Q^{AB/F}\), and SSIM, as well as the detection accuracy measured by the mAP. These results demonstrate that our method can extract comprehensive features and effectively fuse useful information from source image pairs. The findings also highlight the potential of our approach not only for image fusion but also for other CV tasks.

Data availibility

The M3FD dataset underlying this article is available at https://github.com/JinyuanLiu-CV/TarDAL. The FMB dataset is available at https://github.com/JinyuanLiu-CV/SegMiF. The RoadScene dataset is available at https://github.com/hanna-xu/RoadScene. The Harvard Medical dataset is available at http://www.med.harvard.edu/AANLIB/home.html.

References

Zhang, H., Xu, H., Tian, X., Jiang, J. & Ma, J. Image fusion meets deep learning: A survey and perspective. Inf. Fus. 76, 323–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2021.06.008 (2021).

Liu, S. et al. A generative adversarial network based on deep supervision for anatomical and functional image fusion. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 100, 107011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2024.107011 (2025).

Zhou, T., Li, Q., Lu, H., Cheng, Q. & Zhang, X. GAN review: Models and medical image fusion applications. Inf. Fus. 91, 134–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2022.10.017 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Target-aware Dual Adversarial Learning and a Multi-scenario Multi-Modality Benchmark to Fuse Infrared and Visible for Object Detection. In 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 5792–5801, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.00571 (2022).

Li, X., Chen, S., Tian, C., Zhou, H. & Zhang, Z. M2FNet: mask-guided multi-level fusion for RGB-T pedestrian detection. IEEE Trans. Multim. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2024.3381377 (2024).

Hu, T., Nan, X., Zhou, Q., Lin, R. & Shen, Y. A model-based infrared and visible image fusion network with cooperative optimization. Expert Systems with Applications 125639, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2024.125639 (2024).

Tang, L., Yuan, J. & Ma, J. Image fusion in the loop of high-level vision tasks: A semantic-aware real-time infrared and visible image fusion network. Inf. Fusion 82, 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2021.12.004 (2022).

Zhao, Z. et al. CDDFuse: Correlation-Driven Dual-Branch Feature Decomposition for Multi-Modality Image Fusion. In 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 5906–5916, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.00572 (2023).

Jiang, Q. et al. A Contour Angle Orientation for Power Equipment Infrared and Visible Image Registration. IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON POWER DELIVERY 36 (2021).

Ho, J., Jain, A. & Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, NIPS ’20, 12 (Curran Associates Inc., Red Hook, NY, USA), (2020).

Yi, X., Xu, H., Zhang, H., Tang, L. & Ma, J. Diff-retinex: Rethinking low-light image enhancement with a generative diffusion model. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 12302–12311 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Exposurediffusion: Learning to expose for low-light image enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 12438–12448 (2023).

Wu, C. et al. Hsr-diff: Hyperspectral image super-resolution via conditional diffusion models. In 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 7060–7070, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV51070.2023.00652 (2023).

Wu, W., Zhao, Y., Shou, M. Z., Zhou, H. & Shen, C. Diffumask: Synthesizing images with pixel-level annotations for semantic segmentation using diffusion models. In 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 1206–1217, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV51070.2023.00117 (2023).

Guo, L., Wang, C., Yang, W., Wang, Y. & Wen, B. Boundary-aware divide and conquer: A diffusion-based solution for unsupervised shadow removal. In 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 12999–13008, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV51070.2023.01199 (2023).

Zhao, Z. et al. Ddfm: Denoising diffusion model for multi-modality image fusion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 8082–8093 (2023).

Yue, J., Fang, L., Xia, S., Deng, Y. & Ma, J. Diffusion: Toward high color fidelity in infrared and visible image fusion with diffusion models. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 32, 5705–5720. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2023.3322046 (2023).

Yi, X., Tang, L., Zhang, H., Xu, H. & Ma, J. Diff-if: Multi-modality image fusion via diffusion model with fusion knowledge prior. Information Fusion 110, 102450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2024.102450 (2024).

Ma, J. et al. SwinFusion: Cross-domain long-range learning for general image fusion via swin transformer. IEEE/CAA J. Automatica Sinica 9, 1200–1217. https://doi.org/10.1109/JAS.2022.105686 (2022).

Long, Y., Jia, H., Zhong, Y., Jiang, Y. & Jia, Y. RXDNFuse: A aggregated residual dense network for infrared and visible image fusion. Inf. Fusion 69, 128–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2020.11.009 (2021).

Tang, W., He, F., Liu, Y., Duan, Y. & Si, T. DATFuse: Infrared and visible image fusion via dual attention transformer. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 33, 3159–3172. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSVT.2023.3234340 (2023).

Li, H., Wu, X.-J. & Durrani, T. NestFuse: An infrared and visible image fusion architecture based on nest connection and spatial/channel attention models. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 69, 9645–9656. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2020.3005230 (2020).

Li, H., Wu, X.-J. & Kittler, J. RFN-Nest: An end-to-end residual fusion network for infrared and visible images. Information Fusion 73, 72–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2021.02.023 (2021).

Zhao, Z. et al. Efficient and model-based infrared and visible image fusion via algorithm unrolling. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 32, 1186–1196. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSVT.2021.3075745 (2022).

Li, H. & Wu, X.-J. DenseFuse: A fusion approach to infrared and visible images. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 28, 2614–2623. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2018.2887342 (2019).

Ma, J., Zhang, H., Shao, Z., Liang, P. & Xu, H. GANMcC: A generative adversarial network with multiclassification constraints for infrared and visible image fusion. IEEE Trans. Instrum Meas. 70, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2020.3038013 (2021).

Ma, J., Xu, H., Jiang, J., Mei, X. & Zhang, X.-P. DDcGAN: A Dual-Discriminator Conditional Generative Adversarial Network for Multi-Resolution Image Fusion. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 29, 4980–4995. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2020.2977573 (2020).

Guo, Y., Yu, H., Ma, L., Luo, X. & Xie, S. DIE-CDK: A discriminative information enhancement method with cross-modal domain knowledge for fine-grained ship detection. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 34, 10646–10661. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSVT.2024.3407057 (2024).

Xu, M., Tang, L., Zhang, H. & Ma, J. Infrared and visible image fusion via parallel scene and texture learning. Pattern Recogn. 132, 108929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2022.108929 (2022).

Li, H., Wu, X.-J. & Kittler, J. MDLatLRR: A Novel Decomposition Method for Infrared and Visible Image Fusion. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 29, 4733–4746. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2020.2975984 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Ifcnn: A general image fusion framework based on convolutional neural network. Inf. Fusion 54, 99–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2019.07.011 (2020).

Zhang, H. & Ma, J. SDNet: A Versatile Squeeze-and-Decomposition Network for Real-Time Image Fusion. International Journal of Computer Vision 129, 2761–2785. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11263-021-01501-8 (2021).

Xu, H., Ma, J., Yuan, J., Le, Z. & Liu, W. Rfnet: Unsupervised network for mutually reinforcing multi-modal image registration and fusion. 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 19647–19656, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.01906 (2022).

Xu, H., Ma, J., Jiang, J., Guo, X. & Ling, H. U2Fusion: A Unified Unsupervised Image Fusion Network. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 44, 502–518. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2020.3012548 (2022).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In 9th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2021, Virtual Event, Austria, May 3-7, 2021 (OpenReview.net), (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 9992–10002, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.00986 (2021).

Vs, V., Jose Valanarasu, J. M., Oza, P. & Patel, V. M. Image fusion transformer. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), 3566–3570, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIP46576.2022.9897280 (2022).

Wang, Z., Chen, Y., Shao, W., Li, H. & Zhang, L. SwinFuse: A residual swin transformer fusion network for infrared and visible images. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 71, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2022.3191664 (2022).

Liu, Q., Pi, J., Gao, P. & Yuan, D. STFNet: Self-supervised transformer for infrared and visible image fusion. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Topics Comput. Intell. https://doi.org/10.1109/TETCI.2024.3352490 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. MiniViT: Compressing Vision Transformers with Weight Multiplexing. In 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 12135–12144, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.01183 (IEEE, New Orleans, LA, USA), (2022).

Lan, Z. et al. ALBERT: A lite BERT for self-supervised learning of language representations. In 8th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2020, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, April 26-30, 2020 (OpenReview.net), (2020).

Wu, K. et al. Tinyvit: Fast pretraining distillation for small vision transformers. In European conference on computer vision (ECCV) (2022).

Han, D., Pan, X., Han, Y., Song, S. & Huang, G. FLatten Transformer: Vision Transformer using Focused Linear Attention. In 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 5938–5948, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV51070.2023.00548 (IEEE, Paris, France), (2023).

Cui, Y., Ren, W., Cao, X. & Knoll, A. Focal network for image restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 13001–13011 (2023).

Dai, J. et al. Deformable convolutional networks. In 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 764–773, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2017.89 (2017).

Sandler, M., Howard, A., Zhu, M., Zhmoginov, A. & Chen, L.-C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. In 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 4510–4520, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2018.00474 (IEEE, Salt Lake City, UT, 2018).

Tang, L., Deng, Y., Ma, Y., Huang, J. & Ma, J. SuperFusion: A versatile image registration and fusion network with semantic awareness. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 9, 2121–2137. https://doi.org/10.1109/JAS.2022.106082 (2022).

Zhou, H., Wu, W., Zhang, Y., Ma, J. & Ling, H. Semantic-supervised infrared and visible image fusion via a dual-discriminator generative adversarial network. IEEE Trans. Multim. 25, 635–648. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2021.3129609 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. CoCoNet: Coupled contrastive learning network with multi-level feature ensemble for multi-modality image fusion. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 132, 1748–1775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11263-023-01952-1 (2024).

Yi, X., Tang, L., Zhang, H., Xu, H. & Ma, J. Diff-IF: Multi-modality image fusion via diffusion model with fusion knowledge prior. Inf. Fusion 110, 102450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2024.102450 (2024).

Liu, Y., Chen, X., Ward, R. K. & Wang, Z. J. Medical image fusion via convolutional sparsity based morphological component analysis. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 26, 485–489. https://doi.org/10.1109/LSP.2019.2895749 (2019).

Xu, H. & Ma, J. EMFusion: An unsupervised enhanced medical image fusion network. Information Fusion 76, 177–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2021.06.001 (2021).

Fu, J., Li, W., Du, J. & Xu, L. DSAGAN: A generative adversarial network based on dual-stream attention mechanism for anatomical and functional image fusion. Inf. Sci. 576, 484–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2021.06.083 (2021).

Qu, G., Zhang, D. & Yan, P. Information measure for performance of image fusion. Electron. Lett. 38, 313. https://doi.org/10.1049/el:20020212 (2002).

Eskicioglu, A. & Fisher, P. Image quality measures and their performance. IEEE Trans. Commun. 43, 2959–2965. https://doi.org/10.1109/26.477498 (1995).

Han, Y., Cai, Y., Cao, Y. & Xu, X. A new image fusion performance metric based on visual information fidelity. Inf. Fusion 14, 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2011.08.002 (2013).

Xydeas, C. S. & Petrovic, V. S. Objective image fusion performance measure. Electron. Lett. 36, 308–309 (2000).

Wang, Z., Bovik, A., Sheikh, H. & Simoncelli, E. Image quality assessment: From error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 13, 600–612. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2003.819861 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely appreciate the editors and reviewers for their valuable comments. We also wish to thank all the authors who provided source codes and datasets. This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62176174.

Funding

This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62176174.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.H. provided methods and ideas, T.H. completed the experimental design, and T.H. wrote the original draft. T.H. and X.N. reviewed and edited the manuscript. T.H., X.Z., and Y.S. conducted the investigation. X.N. and Q.Z. provided the supervision. Y.S. performed the data formal analysis. X.Z. provided funding support. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, T., Nan, X., Zhou, X. et al. A dual-stream feature decomposition network with weight transformation for multi-modality image fusion. Sci Rep 15, 7467 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92054-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92054-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

CNN–Transformer gated fusion network for medical image super-resolution

Scientific Reports (2025)