Abstract

The fig tree is a multifaceted plant with a wide range of nutritional and health benefits. The employment of the Aksoy weighted classification method, predicated on biological characteristics pertaining to the ripening period, in conjunction with pomological and chemical characteristics of the fresh fruit, yielded favorable outcomes in the assessment of fresh fig quality from eastern Morocco, particularly the OnK Hmam (718) and Chetoui (720) varieties, indicating high quality. From a commercial perspective, the weight of figs is a key factor in determining their value. The study examined the weight of five different varieties of fresh figs, revealing significant variations in their average weight. The Malha fig recorded the lowest average weight of 30.24 g, while the Onk Hmam fig exhibited the highest average weight of 57.25 g. Fresh Chetoui has the highest content of total sugar (15.04%), titratable acid (0.272%), potassium (266.8 mg/100 g), sodium (0.580 mg/100 g), calcium (75.20 mg/100 g) and phosphorus (30.04 mg). Fresh Onk Hmam has the highest fibre concentration (2.60%). Fresh Bounacer has the highest magnesium content (20.52 mg/100 g). Fresh Ghoudane has the highest concentration of iron (1.24 mg/100 g), polyphenols (275.6 GAE/100 g FW) and flavonoids (120.3 QE/100 g FW) among the samples. As fresh figs are seasonal and perishable, the most effective method of preserving their nutritional content and health benefits over an extended period is through the drying process. The primary objective of the drying process is to dehydrate the figs and reduce their water activity to an acceptable level. In addition, the storage and transport costs incurred are economically and commercially advantageous. Sun-dried goudane and chetoui are characterized by their elevated sugar, fiber, mineral, and antioxidant content. Additionally, they exhibit significant volume and weight reduction, thereby reducing packaging requirements and rendering them optimal for use as dietary supplements. In addition, they meet the required criteria of ≤ 26.0% for dry matter and the minimum diameter of 18 mm for black fig (Ghoudane) and 22 mm for white fig (Chetoui) of the European standards. However, it should be noted that their marketability and commercial quality are limited to Category I (65 < maximum allowable fruit count per kilogram ≤ 120), which includes lower quality designations. Dried Ghoudane was found to contain higher levels of polyphenols (380.9 mg GAE/100 g DW) and flavonoids (100.1 mg QE/100 g DW) than dried Chetoui (305.9 mg GAE/100 g DW and 81.90 mg EQ/100 g DW). After sun drying of fresh Ghoudane and Chetoui, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) showed that they had increased levels of phenolic content, titratable acid and minerals. However, total flavonoid content, vitamin C content and soluble solids decreased.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The fig (Ficus carica L.) exhibits considerable variation in terms of its morphology, pigmentation, and flavor, as well as its therapeutic and technological attributes, which vary across different varieties. Many agro morphological descriptors, such as the fruit, stalk and neck length, fruit and ostiole width, fruit shape and weight, are highly useful parameters to characterize, evaluate and differentiate fig genotypes1,2,3. The skin color of the figs exhibited significant variability among the various cultivars. In their study, Hssaini et al.4 ascertained that the cultivars ‘Palmeras’, ‘Breval Blanca’, and ‘Nabout’ possessed the lightest colored figs, which exhibited higher chromatic coordinates (L* and C*) in comparison to other cultivars. In contrast, the dark-colored cultivars ‘Ghoudan’, ‘Noukali’, and ‘Snowden’ exhibited a hue angle (h°) of less than 4°. By contrast, the light-colored cultivars demonstrated a range of values between 95.72° ± 9 and 115.7° ± 15.4. The skin color of the fig is the most visible parameter that growers and consumers use to assess the quality and maturity level of fresh figs1. The variation in fig skin color is dependent on the antioxidant compounds and their amounts, particularly anthocyanins, which were found to be the predominant pigments in figs5. Consequently, the evaluation of skin color using these coordinates is of significant importance in the assessment of fig quality. Numerous studies have underscored the importance of these descriptors by exploring potential correlations between color coordinates and antioxidant compounds6,7,8. The flavor of fig pulp can be categorized as follows: it may be neutral, with little flavor, or aromatic, or it may be strong in flavor2.Typically, the fig varieties are named according to their shape, color, or the geographical region in which they are cultivated9. Ficus carica L. is of the greatest commercial importance among all species of fig and is commonly known as the common fig10. It is a member of the Moraceae family, which contains over 800 species, thus making the Ficus genus one of the most populous among all plant genera11,12 and is native to western Asia and the Eastern Mediterranean13,14. It was one of the first Mediterranean fruits domesticated15,16. This species has evolved significantly over time, transitioning from a wild plant to a cultivated tree. It is speculated that this species may be the first domesticated tree of the Neolithic Revolution, dating back approximately one thousand years before the advent of cereals17.The plant demonstrates versatility in its ability to thrive in various soil and climate conditions18. Figs are harvested at very high moisture levels with an average rate of (79.5 g/100 g), which promotes various types of deterioration and makes the final product highly perishable19. As a result, using the incorrect preservation technique leads to significant losses20. Typically, it is consumed either fresh or dried21. The majority of fig production is consumed in its fresh state. As a result, it is critical to select cultivars with desirable attributes for direct consumption of fresh fruit, such as strong fruity flavor, optimal balance between sweetness and acidity, and commendable post-harvest resilience22. In eastern Morocco, OnK Hmam exhibited the optimal peelability and fruit weight, while Malha demonstrated the most advanced skin cracking resistance23. The presence of short necks, as opposed to long stems, is considered a disadvantage by orchardists due to the challenges it poses during harvesting and the potential damage it causes to the fruit2,3. Varieties such as Malha, which possess short necks, may not be as appealing to growers due to their challenging nature during harvesting. Conversely, varieties like Onk Hmam, with their long necks and stems, are considered more favorable for their ease of harvesting23. The Bounacer, Malha, and Chetoui varieties are distinguished by their globular shape, which is favored in commercial contexts due to its aesthetic appeal and ease of presentation23,24. However, the large ostiole of Onk Hmam facilitates the entry and escape of pollutants and contaminants, rendering this variety unsuitable for the fig sector and storage25. In terms of flavor, Chetoui and Ghoudane are considered the most preferable, owing to their aromatic and sweet characteristics26.

Many fruits must be processed to maintain quality because they are only available in season, including Fig27. According to the United States Department of Agriculture data, dried fig has the highest nutrient score of any dried fruit because it is an important source of vitamins and minerals. Fig is high in iron, proteins, calories, and fiber. It contains more calcium than milk. The nutritive index of fig is 11, as opposed to 6, 8, and 9 for date, raisin, and apple, respectively28. Figs contribute to maintaining a balanced diet due to their significant amount of easily digestible carbs (more than 53%), low fat content, and absence of cholesterol. Figs are rich in vitamins (C, B1, B2, B5, PP, and K) and minerals (calcium, potassium, phosphorus, and magnesium). They also include a significant amount of dietary fiber, with a content of 8 g/100 g29. Antioxidants, including beta-carotene, lycopene, and vitamins C, E, and A, are compounds that have the capacity to protect cells from damage inflicted by unstable molecules, termed ‘free radicals’. Antioxidants have been found to interact with and stabilize such radicals, thereby preventing some of the damage they would otherwise cause. It is widely accepted that free radical damage may lead to the development of cancer30. Minerals are vital components of our diet, playing an indispensable role in a variety of human functions. They serve as the fundamental elements for our skeletal structure, influence muscle and nerve activity, and regulate the body’s hydration balance. Furthermore, minerals are integral components of hormones, enzymes, and other biologically active substances31. It is critical to note that a number of minerals assume an indispensable role in optimising immune system functionality. The innate and adaptive immune systems are influenced by the presence of minerals. Consequentially, the bioavailability of minerals has been demonstrated to influence susceptibility to pathogens and the development of chronic diseases32,33. Traditional drying processes are used by farmers to extend the shelf life of figs and keep them available throughout the year, while faster artificial drying technologies are used at the industrial level to ensure a large quantity of produce for commerce. Artificial drying technologies have been shown to offer several advantages over traditional methods. Firstly, they exhibit faster drying kinetics and better thermal efficiency. Secondly, they produce dried products of a higher quality in terms of color, aroma, texture, safety, and nutrition retention34. The fig fruit has significant commercial value because it is used in jam, beverages, pasta, and other products35. In the contemporary era, the fig (Ficus carica) has attained significant global importance as a crop, cultivated for both dry and fresh consumption, due to the substantial international trade in this produce. As Aksoy asserts, since the late 19th century, Turkey has been a leading producer and trader of fresh and dried F. carica. Turkey has consistently maintained its dominance in the global trade of dried F. carica, consistently ranking among the top producers and exporters. As time has passed, there has been a change in the way the crop is produced, with developed countries (Greece, Spain, Portugal, Italy and the USA) becoming less competitive due to the high demand for labour, and developing countries (Iran, Morocco and Egypt) becoming more prominent in the global market. The dried F. carica production in some traditional producers, such as Italy and Spain, or new countries, such as China, continues with high added-value products destined for high-end markets36. Figs are recommended for children, pregnant or breastfeeding women, the elderly, athletes, hard workers, and anemics37,38,39. Bioactive compounds like ferulic acid, 3-O- and 5-O-caffeoylquinic acids, quercetin-3-O-glucoside, quercetin-3-O-rutinoside, psoralen, bergaptenn, gallic acid, syringic acid, catechin, epicatechin, luteolin, 6 C-hexose-8 C-pentose, and apigenin-rutinoside have been found in the pulp and peels of different kinds of figs. These antioxidants hold significant pharmacological and health implications40,41,42. The presence of low levels of antioxidants, or the inhibition of antioxidant enzymes, has been demonstrated to induce oxidative stress, a condition which can result in the damage or death of cells. Given the potential significance of oxidative stress in the aetiology of numerous human diseases, there has been intensive research focused on the use of antioxidants in pharmacology, particularly in the context of stroke and neurodegenerative diseases43. However, the role of oxidative stress as either a causative agent or a consequence of disease remains to be fully elucidated. Antioxidants are also widely used as ingredients in dietary supplements with the aim of maintaining health and preventing diseases such as cancer and coronary heart disease43. Although initial studies suggested that antioxidant supplements might promote health, subsequent large-scale clinical trials did not detect any benefit and instead suggested that excessive supplementation may be harmful. In addition to these uses of natural antioxidants in medicine, these compounds have many industrial applications, such as preservatives in food and cosmetics, and preventing the degradation of rubber and gasoline43,44.

Because the Ahfir area leads in fig production, the active Gharmawne cooperative partners with the municipality and other agricultural innovators to organize the Aghbal Fig Festival every year on the last weekend of August. This social and commercial event aims to unite eastern Morocco’s fig producers and consumers, advance fig commerce and related products, support local small farmers’ creativity, and showcase the area’s natural and cultural highlights. By emphasizing the potential of this industry, encouraging the sharing of knowledge and experiences between farmers and experts, and investigating methods to advance fig tree cultivation in this region through planting, expert planning, and producer supervision, this festival seeks to promote this product as well as its quality and varieties. This research aims to provide a thorough and accessible study of the nutritional value and health benefits associated with the consumption of fresh or dried figs from Ahfir, the main producer in eastern Morocco. It will also determine the quality of five varieties of fresh fig: Bounacer, Chetoui, Ghoudane, Malha, and Onk Hmam, which are characteristic of the region, using the Aksoy weighted classification method. This evaluation is carried out according to the following parameters: attractiveness, physical characteristics of the fruit, market value, organoleptic properties, and availability of the fruit during the designated production season, optimal presentation of the fig, and storage conditions. This thorough evaluation is carried out by analyzing the biological traits related to the ripening phase, in addition to the pomological and chemical characteristics. In addition, the quality of sun-dried figs from Chetoui and Ghoudane was assessed using the UNECE DDP-15 standard for marketing and commercial quality control of dried figs. In addition, using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) as a multivariate statistical technique that allows reducing the number of variables applied to individuals while maintaining the integrity of the information, the effect of this solar drying on the physicochemical properties, bioactive components, and antioxidant activity of Ghoudane (as a dark fig) and Chetoui (as a light fig) was investigated. By extrapolating the findings, it will be possible to confirm or deny the importance of the biodiversity of these fruits in the region and to identify new ways of using these varieties in order to increase their economic benefit and valorization through their characteristics.

Materials and methods

Materials sampling and drying process

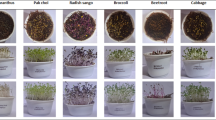

In order to evaluate the quality of figs (Ficus carica L.) in eastern Morocco, five local fresh fig varieties grown in Ahfir and belonging to the common fig type were selected because they are representative of the wider diversity in the region and are important for their nutritional/commercial value and productivity. The Chetoui (CH), Malha (MA) and Onk Hmam (OH) varieties are uniferous fig trees that produce only parthenocarpic (the development of fruit without fertilization) autumn figs, commonly known as “karmos”. In contrast, the Bounacer (BN) and Ghoudane (GD) varieties have biferous characteristics, producing parthenocarpic flowering figs known as “bakor” during the spring season and parthenocarpic “karmos” figs during the autumn season. Parthenocarpic plants produce fruit without pollination, ensuring a consistent fruit set even in environments where pollinators are scarce or weather conditions are unfavorable. Parthenocarpic fruits are often seedless or have fewer seeds, resulting in improved fruit quality and potentially better taste and texture. The plant voucher specimen is deposited in the herbarium of the University of Mohammed Premier, Oujda, Morocco (HUMPO 100). Fresh figs were sampled from traditional farmer-owned orchards with mature trees (over 10 years old) in four different locations (Almahsar, Gharmawen, Ouled Mansour, and Sidi Rahmoun) in eastern Morocco, mainly around AHFIR, the leading producer of this fruit (Fig. 1). Samples of 200 fresh figs (ten fruit per tree and five trees per variety in each location for two consecutive years, 2023–2024). Samples were taken from the most mature, disease-free basal fruit, collected at mid-ripening. The figs were collected and immediately taken to the laboratory, mixed, and then freeze-dried.

Due to the lack of a drying oven, only the highly productive and compatible CH and GD varieties are sun-dried. Producers frequently employ this strategy to regulate the fresh fig market and get enhanced economic benefits. Additionally, it helps to improve the longevity, storage capability, and financial viability of the figs on the market. Ripe figs from the same study sites were collected and sun-dried by the Gharmawen cooperative. Figs are placed in baskets or boxes where they are not stacked on top of each other to avoid spoilage. Then the figs are placed in the place we have allocated for the drying process, boxes or reed mats, and they must be in a place high above the ground. The use of reeds enables air to penetrate between the figs to dry out any moisture present. The stand is lifted off the ground to enable air to enter on the underside to facilitate the entry of air currents to dry the liquids coming down from the fruit. Spread the figs out well and turn the figs over every 1 or 2 days to achieve uniform drying, the fruits are turned over daily and left overnight to prevent spoilage. For white figs, we turn them over when the whiteness is taken from the side exposed to the sun, and black ones when the tenderness decreases from the top side, which we feel with our hands. The process lasts depending on the external humidity and temperature during the day. The drying time ranges from six to seven days. Dry figs are those that have flexibility to the touch and do not allow syrup to flow under pressure between the thumb and index finger26. To perform this investigation, 3 kg of each dried fig variety were collected from the four study locations.

Extraction process

Maceration extraction is predicated upon solid-liquid separation, with an organic solvent or water constituting the liquid phase. The predominant solvents employed for the extraction of phenolic compounds are methanol, ethanol, water, or a combination of these solvents45,46. The carbon chain of ethanol, being only two carbons long, is not very long, and thus it is miscible with water and can also dissolve a wide range of molecules, including both slightly polar and slightly non-polar molecules. This makes it an effective solvent for many flavor compounds, coloring agents, and bioactive or medicinal compounds. It has been generally established that aqueous or acetone is suitable for extracting greater molecular weight flavanols, whereas methanol is more successful for extracting lower molecular weight polyphenols47,48. The selection of ethanol is attributed to its reputation as a safe substance for human consumption and its efficacy as a solvent for extracting polyphenols48. Maceration in 95% hydro-ethanol ( Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was used to extract chemicals from several varieties of fresh or dried figs. 30 g of crushed figs were combined with 300 mL of extraction solvent and macerated at room temperature and in the dark for 24 h, stirring occasionally47. The extract was filtered via Whatman n◦1 filter paper. The liquid extracts were promptly tested to assess the amounts of the bioactive chemicals under investigation, as well as their antioxidant properties. This is in addition to the titratable acidity (%), total soluble solids (Brix), total sugars, and vitamin C.

Assessment of biochemical characteristics in fresh and dried figs

Determination of bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity

These analytical procedures were conducted in triplicate during the harvest season to ensure the accuracy of the results.

Analysis of the total polyphenol content

The dry extract was stored in the refrigerator at 4 °C until use. The Folin-Ciocalteu (FC) reagent49,50, was used to measure the total phenolic content (TPC) of the extracts. 100 µL of the extract was mixed with 500 µL of FC (Oxford Range of Laboratory Chemicals, Maharashtra, India) and 400 µL of 7.5% (w/v) Na2CO3(Sigma-Aldrech, Darmstadt, Germany). Before measuring absorbance at 760 nm, the mixture is agitated and incubated at room temperature for 10 min in the dark. Compare the results to the gallic acid (Sigma-Aldrech, Darmstadt, Germany) calibration curve, which is mg gallic acid equivalent (GAE) /100 g of fresh or dry weight.

Analysis of the total flavonoid content

The total flavonoid content (TFC) concentration was measured using the AlCl3 method51. The test involved mixing 500 µL of each extraction with 1500 µL of 95% ethanol, 100 µL of 10% (w/v) AlCl3 (LobaChemie, Mumbai, India), 100 µL of 1 M sodium acetate (Sigma-Aldrech, Darmstadt, Germany), and 2.8 mL of distilled water. For 30 min, the mixture is incubated at ambient temperature in dark settings. Replace the extraction with 95% ethanol to make the blank, and then measure the absorbance at 415 nm47. As a standard, quercetin (QE) (Sigma-Aldrech, Darmstadt, Germany) was used to quantify the extractions’ TFC as mg of QE equivalent/100 g of fresh or dry weight of the sample. Ascorbic acid (Thermo Fisher Scientific, New Jersey, USA) was employed as a positive control.

2,2-diphényl 1-picrylhydrazyle radical scavenging assay

Different concentrations of each extract and ascorbic acid standard were generated (5 to 500 µg/mL). Each concentration of extract or standard was added to 2.5 mL of the prepared 2,2-diphényl 1-picrylhydrazyle (DPPH) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, New Jersey, USA) ethanol solution (2 mg DPPH/100 mL ethanol) to make a final volume of 3 mL. After 30 min at room temperature, absorbance at 515 nm was measured against a blank (all reagents except the extract or standard)26,52. Using the following formula, the DPPH free radical scavenging activity was estimated in percentage (%):

IC50 values were determined graphically from the curve of antioxidant concentration (mg/mL) versus percentage of inhibition, generated by GraphPad Prism 8.

Evaluation of macronutrients, vitamin C, and minerals

It should be noted that all of the said analytical methodologies were executed in triplicate during the designated harvest season. Total sugars were determined using the DUBOIS (colorimetric) method53, whereas protein was measured according to the Kjeldhal method54. Lipid content was evaluated by means of methodologies approved by the American Association of Cereal Chemists (AACC) (2000), after extraction of samples using non-polar organic solvents and Soxhlet extraction equipment55. As for the dosage of dietary fibre, this is appropriate in accordance with the approach specified in AOAC 985.29, as endorsed by Pereira et al.56. The 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP) (Sigma-Aldrech, Darmstadt, Germany) spectrophotometricmethod used for the concentration of ascorbic acid (Asc A) is measured in mg/100 g57. The mineral content was determined using atomic absorption with a flame approach for the tests of Ca, Mg, K, Na, and Fe58, while the amount of phosphorus was measured using the spectrophotometric molybdovanadate technique59.

Titratable acidity (%) and total soluble solid or Brix (%)

Chemical assays were performed in triplicate during the specified harvest season, focusing on acidity and Brix as indicators of fruit ripeness. These parameters are crucial for evaluating the pomological quality of figs and can also aid in distinguishing between different varieties. The titratable acidity of fig juice was assessed using the AFNOR method (NF V O5-101, 1970), with the results represented as a percentage of citric acid. The process involved performing a titration with the sodium hydroxide NaOH (Sigma-Aldrech, Darmstadt, Germany) (0.1 M) until the pH reached 8.1 while utilizing phenolphthalein (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) as colored indicator60. The Brix index quantifies the collective amount of dissolved solids in figs, whether they are fresh or dried. Brix measurements were obtained using a digital refractometer (HANNA NUMERIQUE HI 96801- ECHELLE 0–85% BRIX, France)26.

Fresh Fig descriptors and quality

The International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI), based in Rome, Italy, in collaboration with the International Centre for Advanced Agricultural Studies in the Mediterranean (CIHEAM), based in Paris, France, has developed a set of descriptors for fig evaluation2 .The assessment of the quality of fresh figs is facilitated by the utilization of Aksoy’s weighted ranking method, encompassing seven attributes within the fig evaluation descriptors. One of these attributes pertains to the biological characteristic of the ripening period, which, if coinciding with the onset or offset of the fig fruit season, results in an escalation in marketing value due to heightened demand and diminished competition). Six attributes (weight of fruit; shape of fruit (index); fruit skin cracks; ease of peeling; neck length; ostiol width) are related to the fresh fruit itself and are related to its attractiveness, marketing value, ease of presentation, peeling and consumption, safety, and preservability (Table 1). Two biochemical characteristics—total soluble solids (TSS) and titratable acidity (TA)—are added to these attributes as they are indicative of the organoleptic characteristics of the figs and their ripeness. This multifaceted methodology thus captures the comprehensive concept of the fresh fig quality from the perspectives of all involved parties, i.e., the producer, the seller, and the consumer2,61.

As delineated in Table 2, the nine components of Aksoy’s weighted ranking method, which was utilized to evaluate the quality of fresh figs based on their weight, various point factors, and classifications, are elucidated.

The following two relationships are utilized in order to ascertain the quality of figs:

The total weight is thus equivalent to 100, which is then divided by the nine characters used in the method.

Marketing and quality of dried figs

As per the UNECE DDP-15 Standard of the UN Economic Commission for Europe about the marketing and commercial quality control of dried figs62, the level of moisture in untreated dried figs shouldn’t be higher than 26.0%. The dried fig chunks were dried out in an oven (WTB Binder, 120 Tuttlingen, Germany) at 105 °C, and the results were given in percentages26. The caliber of whole dried figs is measured by either the number of fruits per kilogram or the diameter of the fruit. The maximum allowable fruit count per kilogram is 65 for “Extra,” 120 for category I, and greater than 120 units for category II. Calibration based on diameter requires a minimum diameter of 18 mm for black fig and 22 mm for white fig. Table 3 illustrates the correlation between the number of fruits per kilogram and the corresponding fruit standard.

Statistical analysis

The correlation coefficients for spectrophotometric tests were calculated with the Microsoft Office Excel 2021 software (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). The statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics V21.0 software for descriptive statistics, comparing averages using the t-test of studied characteristics and ANOVA using post hoc testing (Tukey’s test) at the 5% threshold, bivariate Pearson correlation analysis with a significance level of P < 0.01, and principal component analysis (PCA).

Results and discussion

Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity evaluation

The study (Fig. 2) showed that the hydroethanol extract FGD (275.6 ± 4.56 mg GAE/100 g FW) had the highest polyphenol concentration. This was followed by FOH (260.5 ± 2.16 mg GAE/100 g FW), FBN (245.0 ± 3.03 mg GAE/100 g FW), FCH (237.9 ± 2.15 mg GAE/100 g FW), and FMA (183.4 ± 2.28 mg GAE/100 g FW). With the exception of FBN and FCH, the ANOVA study of TPC, using a 5% significance threshold, shows significant differences between varieties. Solomon et al. studied the distribution of TPC in six varieties of fresh figs and found that Kadota had the lowest (48.6 ± 3.8 mg GAE/100 g FW) and Mission the highest (281.1 ± 3.0 mg GAE/100 g FW)63. Caliscan and Polat investigated the polyphenol content of seventy-six different fig varieties from the eastern Mediterranean region of Turkey. Their results showed that the TPC values were in the range of 28.6 to 211.9 mg GAE/100 g FW64. The FMA results were within this range, while the results of the other varieties studied exceeded the maximum value for this range. Harzallah et al. found very high amounts of TPC in three varieties of fresh Tunisian figs: Bidhi (green), Hamri (purple), and Kohli (black)—almost 30 mg GAE/g FW to 60 mg GAE/g FW65. The amount of phenolic compounds varies greatly depending on the skin color of the fruit, with darker-skinned figs containing the most active compounds63,64,65. This is consistent with our results, as the skin color of the figs is black for GD, purple with green spots for OH, black more than purple for BN, green with purple spots for CH, and green for MA23.

Total polyphenols content of different fresh and dried figs. FBN, Fresh Bounacer; FCH, Fresh Chetoui; FGD, Fresh Ghoudane; FMA, Fresh Malha; FOH, Fresh Onk Hmam; DCH, Dried Chetoui; DGD, Dried Ghoudane. The ANOVA of 5% indicates that the fresh figs are significantly different, as indicated by the difference in lowercase letters. The t-test shows a significant difference between the dried figs, as indicated by the difference in capital letters.

The analysis (Fig. 2) shows that the hydroethanol extract DGD has the highest concentration of polyphenols (380.9 ± 2.352 mg GAE/100 g DW), whereas the hydroethanol extract DCH has the lowest (305.9 ± 2.307 mg GAE/100 g DW). According to the t-test with 5% threshold, the difference in polyphenols between DGD and DCH is statistically significant. There are several factors that influence the measurement of polyphenol extract. These include the method used for quantification (such as a colorimetric assay or HPLC analysis) and the way in which the sample was extracted (such as the type and concentration of solvent, the temperature and time of extraction, the ratio of sample to solvent, and the number of extractions). The limited specificity for the FC reagent is the main drawback of the colorimetric assay. This reagent has a high sensitivity to reducing hydroxyl groups. These include those present in phenolic compounds as well as various carbohydrates and proteins66.

Total flavonoids content of different fresh and dried figs. FBN, Fresh Bounacer; FCH, Fresh Chetoui; FGD, Fresh Ghoudane; FMA, Fresh Malha; FOH, Fresh Onk Hmam; DCH, Dried Chetoui; DGD, Dried Ghoudane. The ANOVA of 5% indicates that the fresh figs are significantly different, as indicated by the difference in lowercase letters. The t-test shows a significant difference between the dried figs, as indicated by the difference in capital letters.

The hydroethanol extract results (Fig. 3) show that FGD (120.3 ± 0.70 QE/100 g FW) contained the greatest concentration of flavonoids. This was followed by FOH (118.4 ± 0.35 QE/100 g FW), FBN (103.5 ± 1.89 QE/100 g FW), FCH (98,50 ± 2.05 QE/100 g FW), and FMA (61.77 ± 4.14 QE/100 g FW). Using a 5% significance threshold, the ANOVA analysis of TFC reveals significant differences between the varieties except for FGD with FOH and FBN with FCH. The dispersion of TFC among six distinct varieties of fresh figs was examined by Solomon et al. The concentrations were found to range from 2.1 ± 0.2 mg catachin E/100 g FW for Mission to 21.5 ± 2.7 mg catachin E/100 g FW for Kadota63. Harzallah et al. identified significantly elevated levels of TFCs in three distinct Tunisian varieties of raw figs: At its minimum, Bhidi comprised approximately 2 mg of catachin E/g FW, whereas Kohli reached 12.75 mg of catachin E/g FW65. Flavonoids have powerful pharmacological effects as radical scavengers, making them vital to human health67. The research results (Fig. 3) show that the DGD hydroethanol extract has the most flavonoids (101.1 ± 2.052 mg QE/100 g DW), while the DCH hydroethanol extract has less (81.90 ± 1.646 mg QE/100 g DW). The t-test, employing a 5% significance level, identifies a statistically significant difference in flavonoid content between dry GD and CH figs.

Dark-peeled fig varieties are more abundant in flavonoids, polyphenols, and anthocyanins than their lighter-peeled counterparts. Black fig peel may contain an abundance of natural antioxidants. When eating fruit, consumers often omit the fig peel. Nevertheless, peels are notably rich in phenolic compounds, which function as antioxidants and shouldn’t be disregarded. In fact, it is advisable to consume fully ripe fruits either fresh or in juice form40,65. Numerous variables affect the phytochemical composition of plant material, including phenological stage, genotype, ecophysiological conditions, and cultivation methods. The compositional quality and biological activities of fruits are determined by a series of biochemical, physiological, and structural changes that occur during growth and maturation. As a result, the phenological stage is the most significant factor for fruits68.

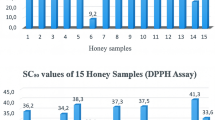

The study’s results (Table 4) indicate that all of the hydroethanol extracts assessed exhibited the ability to scavenge DPPH radicals. However, the extent to which these extracts scavenged free radicals varied significantly depending on the fig variety and the fruit’s state (fresh or dried). The two dried extracts exhibited the highest antioxidant activity. The dried extract DGD has the maximum potency, as seen by its lowest IC50 value (4.60 ± 0.14 mg/ml). The fresh extracts follow in descending order of potency, with FGD being the strongest, followed by FOH, FBN to FCH, and finally the FMA extract, which is the weakest with the highest IC50 value (12.42 ± 0.64 mg/ml). Harzallah et al. found DPPH IC50 DPPH scavengers in three Tunisian fresh fruit cultivars, ranging from 7.04 ± 0.15 mg/ml for Hamri to 14.6 ± 0.62 mg/ml for Bidhi. Using a 5% significance level, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) on the DPPH IC50 reveals significant variations among the extracts, excluding certain combinations (DCH/FGD, FGD/FOH, FOH/FBN, and FBN/FCH).

The application of bivariate Pearson correlation analysis revealed a significant negative correlation (correlation coefficient = − 0.804) between TPC and DPPH IC50, as well as a highly negative correlation (correlation coefficient = − 0.731) between TFC and DPPH IC50. These results demonstrate that the activity of removing DPPH free radicals is related to the polyphenol and flavonoid components present in the fresh and dried Ficus carica extracts under investigation. These results confirm that both fresh and dried fig fruits from eastern Morocco possess an antioxidant activity derived from their composition of bioactive compounds, especially polyphenols (phenolic acids, flavonoids, stilbenes and lignans).

Macronutrients, vitamin C and minerals assessments

The amounts of macronutrients and vitamin C in each of the varieties of fresh and dried figs analyzed are provided in Table 5.

The present investigation focused on the analysis of five fresh figs (FBN, FGD, FOH, FCH, and FGD). The analysis indicated that the levels of lipids present in the samples were low, with FCH exhibiting the highest level of content (0.20 ± 0.01%), while FOH (0.10 ± 0.01%) and FGD (0.10 ± 0.02%) exhibited the lowest levels. A one-way ANOVA at a 5% level of significance was conducted, which demonstrated that a substantial difference exists between the varieties in their lipid content, with the exceptions between FBN and FMA on the one hand and between the trio FBN, FGD, and FOH on the other.

Despite their low content, lipids have a significant impact on storage time, organoleptic characteristics, nutritional value, and biological value. Additionally, fig lipids have a high level of unsaturation (> 68%) of acid monovalent fats, with most of them being polyunsaturated. This may help explain why the oxidative breakdown of figs and their derivatives happens69.

In this study, the protein and the dietary fiber content of the five different fresh fig varieties was analyzed. The findings revealed that FCH (1.24 ± 0.12%) had the highest protein content, while FMA (0.86 ± 0.32%) had the lowest. Furthermore, FOH (2.60 ± 0.08%) was found to have the greatest amount of dietary fiber, and FMA (2.24 ± 0.21%) had the least fiber content. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) at the 5% level indicates that no statistically significant differences exist among the fresh fig varieties studied with respect to these two characteristics.

Plant proteins aren’t as biologically valuable as animal proteins, yet they’re nonetheless vital to human nutrition, serving as enzymes, transporters, and even a defence agent70. As Kulkarni et al. (2005) suggest, an increase in the total protein content can be attributed to the acceleration of ripening changes that initiate an array of enzyme activities71. Conversely, a decrease in total protein content may result from a reduction in demand for endogenous enzymes linked to anabolic activities, which diminish alongside fruit development and maturity72.

Dietary fiber is an important factor in the prevention of chronic diseases. High fiber intake reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease, constipation, some cancers, hypertension, diabetes, and obesity. In addition, dietary fiber has therapeutic value in the treatment of coronary heart disease (CHD), hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and gastrointestinal disorders. An overwhelming consensus now recommends five to six servings of fruit and vegetables a day for a dietary fiber intake of 20 to 35 g/day or 10 to 13 g/1000 kcal for healthy adults73.

With regard to the sugar content, it is evident that FCH exhibits the highest concentration (15.04 ± 0.01%), while FMA demonstrates the lowest concentration (11.84 ± 0.42%). In the context of this component, the analysis of variance (ANOVA) at the 5% level reveals significant variations among the varieties, with the exception of the comparisons between FCH and FGD, and between FOH and FBN.

The sugar content of fruits affects their organoleptic properties, stability, and preservation. It can also be used to assess ripeness74. Despite being classified as climacteric, with an increase in respiration rate and ethylene production at the onset of ripening, figs harvested before full ripeness fail to meet the commercially acceptable standards of size, color, flavor, and texture. Conversely, when harvested late, the figs tend to perish due to over-ripening and heightened susceptibility to pathogens75. Fig fruit development follows a typical double sigmoid growth curve based on fruit diameter, with two rapid growth phases (I and III) separated by the slower growth phase II76. In particular, the ripening process (phase III) of the summer crop fig is extremely rapid, occurring within a week and as little as 3 days during the peak summer season. Accordingly, ripening-related parameters such as size, flavor, and texture undergo major changes within a short period of time. Compared to the seemingly uneventful Phase II, fruit size can increase up to two to three times, and softness increases dramatically during Phase III77. In terms of fruit sweetness, more than 70% of the total dry weight and 90% of the total sugar content accumulate in the fruit during ripening76. Sweetness is perhaps the most important indicator of fig fruit quality and is determined by the concentration of soluble sugars. Ripe figs are very high in sugar, and sugar accumulation is a developmental process. Sugar levels remain low during stages I and II of development, and concentrations increase significantly during the final stages of ripening until harvest76. Fig is a monosaccharide-accumulating fruit, with the main soluble sugars being glucose (Glc) and fructose (Fru), the products of sucrose (Suc) hydrolysis; Suc is also present, but at low concentrations, and starch concentrations tended to decrease from fruit emergence to fruit ripening78.

The analysis of vitamin C content in the five various varieties revealed significant disparities, as indicated by an ANOVA test with an error margin of 5%. The highest recorded concentration of vitamin C was detected in FCH (6.04 ± 0.04 mg/100 g), while the lowest concentration was in FBN (4.12 ± 0.02 mg/100 g).

Vitamin C, the most vital vitamin in fruits and vegetables, prevents scurvy and maintains healthy skin, gums, and blood vessels. Vitamin C has numerous biological activities, including collagen production, iron absorption, cholesterol reduction, nitrosoamine suppression, immune system strengthening, and action against free radicals. As an antioxidant, vitamin C may lower the risk of cardiovascular illnesses, arteriosclerosis, and some cancers79. During the maturation of the fruit, the rate of ascorbic acid accumulation is greatest at the late stages of fruit development and continues to increase as the fruit reaches full maturity and begins to ripen80. Vitamin C, which includes ascorbic acid and dehydroascorbic acid, is essential for food quality in many horticultural crops due to its biological effects in the human body. Many variables influence the variation in vitamin C content in fruit, including fruit variety, post-harvest handling conditions, pre-harvest environmental variables (e.g. sun exposure, cultural practices, ripeness, harvesting method) and genetic characteristics26.

These five studied compounds’ findings of these fresh fruit from the eastern Morocco are consistent with the study outcomes conducted by the Informatics Centre on Food Quality “CIQUAL” and the National Centre for Veterinary and Food Studies “CNEVA” for freshly harvested figs19.

The analysis of the five aforementioned studied parameters on the two dried fig varieties revealed that, with the exception of vitamin C, they exhibited higher levels of richness in comparison to the five fresh fig varieties that were tested. Of the two dried fig varieties, DCH demonstrated the highest levels of lipids (1.30 ± 0.04%), protein content (3.52 ± 0.15%), total sugars (54.42 ± 0.25%), and vitamin C (1.14 ± 0.01 mg/100 g). In contrast, DGD demonstrated the highest levels of dietary fiber (6.15 ± 0.12%). A statistically significant discrepancy was observed between the two dried fig varieties, DCH and DGD, across all the evaluated quantitative parameters (t-test at a significance level of 5%), with the exception of protein content, which did not reach statistical significance.

The findings indicate that the levels of lipids, proteins, total sugars, and vitamins C observed in both dried varieties are consistent with the anticipated results from the CIQUAL-CNEVA analysis for dried figs. However, discrepancies are observed in the results for dietary fiber, with the findings from both varieties demonstrating a lower level of dietary fiber compared to the expected CIQUAL-CNEVA results for dried figs19.

On the basis of the results obtained (Table 6), potassium emerges as the dominant mineral element in both fresh and dry fig samples examined in comparison to the remaining minerals under investigation.

FCH has the highest concentrations of potassium K (266.8 ± 0.50 mg/100 g), sodium Na (05.80 ± 0.11 mg/100 g), calcium Ca (75.20 ± 1.05 mg/100 g), and phosphorus P (30.04 ± 0.08 mg/100 g). FBN has the highest concentration of magnesium at Mg (20.52 ± 0.12 mg/100 g), whereas FGD has the highest concentration of iron at Fe (1.24 ± 0.14 mg/100 g).

FOH content is the lowest in potassium K (218.56 ± 0.11 mg/100 g) and phosphorus P (24.75 ± 0.15 mg/100 g). In terms of the elements sodium Na (4.48 ± 0.15 mg/100 g), calcium Ca (59.24 ± 1.12 mg/100 g), magnesium Mg (16.25 ± 0.12 mg/100 g), and iron Fe (0.78 ± 0.10 mg/100 g), FMA exhibits the lowest values in each category.

The analysis of the studied mineral composition of these five varieties of fresh figs from eastern Morocco is in line with the results of the CIQUAL-CNEVA research on fresh figs19. A one-way standard analysis of variance at a 5% level revealed significant variations in K and P between the fresh fig varieties. There are no significant variations in sodium or magnesium levels between FBN, FGD, and FOH. The changes in calcium levels are not substantial. There are three scenarios to consider: FGD/FBN, FBN/FOH, and lastly, FOH/FMA. The same is true for iron; it is not expressed between FGD/FCH/FOH, FBN/FCH/FOH, and FBN/FMA.

The mineral composition of the studied dried figs clearly shows that DCH contains a higher amount of potassium K (756 ± 0.15 mg/100 g), sodium Na (53.76 ± 0.12 mg/100 g), calcium Ca (161.6 ± 1.18 mg/100 g), and phosphorus P (82.76 ± 0.12 mg/100 g) than DGD. Conversely, DGD stands out for its notably higher magnesium content of magnesium at Mg (102.40 ± 0.16 mg/100 g) and iron level at Fe (3.76 ± 0.12 mg/100 g) compared to DCH.

The t-test (5% threshold) revealed significant variations in the studied mineral content between DCH and DGD .

The mineral composition of these two sun-dried fig varieties from eastern Morocco has been found to correspond with the findings of the CIQUAL-CNEVA research on dried figs, with the exception of two instances related to DGD, which has been found to be somewhat lower in potassium (K) and higher in magnesium (Mg)19.

Since potassium is a mineral that helps control blood pressure, eating figs can be advantageous for individuals with high blood pressure. Additionally, the presence of potassium in figs can counterbalance the elevated excretion of calcium in urine resulting from high-salt meals, aiding in the prevention of accelerated bone loss58.

The mineral composition of figs has been shown to closely resemble that of human milk, with iron being of particular significance81. Indeed, the iron content of Ficus carica has been reported to be 50% that of beef liver82.

Furthermore, in the study by O’Brien et al. (1998), Ficus carica was identified as the preferred dietary source of calcium for plant-eating birds82. Consequently, the findings collectively indicate the potential of Ficus carica as a dietary supplement to prevent osteoporosis83.

Numerous recent studies have shed light on the antimicrobial properties of specific mineral products used in medicine. Minerals can work together to make things better by changing the pH on their own or with bioactive compounds from plant extracts, like flavonoids, terpenoids, and polyphenols. These interactions may affect the extract’s antibacterial activity as well as the plant’s antimicrobial properties, depending on the precise chemical components present in bioactive compounds and minerals26.

For countless generations, figs have been a staple of the health-promoting Mediterranean diet63. Fresh or dried figs have been shown to possess both intellectual and physical fortifying properties. In comparison with other commonly consumed fruits, such as apples, dates, and grapes, figs provide a higher concentration of calories, dietary fibre, potassium, calcium, iron, and vitamins84.

This study posits that Ahfir fig varieties, in particular, serve as a notable source of nutritive and healthy compounds, including sugars, minerals, and polyphenols.Notably, these findings represent one of the inaugural research endeavours focused on fig fruits cultivated in eastern Morocco. The findings of this study hold significant potential for utilization in various applications, including fresh consumption, drying, and the production of diverse products such as jam, syrup, coffee, vinegar, and alcohol.

Fresh autumn Fig quality

In addition to the TSS/TA, Table 7 displays the results of the Aksoy weighted classification method, as well as the results of the nine components used in its determination.

Fruit ripening begins early for FBN and FGD [July 20–31], mid-season for FMA [August 1–15], and late for FOH and FCH [August 15–31]. In terms of production, the AHFIR fig sector offers significant benefits, including early harvests and a high availability of fresh fruits on the market, as well as a longer harvest period that allows for a long-term supply of fresh figs. The early ripening technique, which involves brushing a small drop of oil onto the ostiol of figs, allows producers to boost uniform production and speed up the ripening process, all of which contribute to the CH variety’s increased commercial profit. It takes about 5 to 8 days for the treated figs to reach maturity85.

Owino et al. (2006) validated the role of ethylene in the ripening of figs with olive oil. This team investigated the regulatory mechanisms of ethylene biosynthesis in figs treated on the tree in response to three substances: olive oil, auxin, and ethephon. The results suggest that ethephon and olive oil stimulate fig growth faster than auxin. In fact, the ‘on tree’ figs treated with olive oil and ethephon matured after approximately 7 days, whereas the auxin-treated fruit ripened 10 days later. The untreated fruit ripened after 14 days86. So ethylene biosynthesis induced by olive oil (or certain vegetable oils) is a unique feature that has only been reported in figs85,86.

In the fresh fig business, the shape or index [index (fruit width/fruit length) = I] is especially essential. The research found that the FGD (0.69 ± 0.08) and FOH (0.74 ± 0.04) varieties have an oblong shape (I < 0.9), while the FBN (0.92 ± 0.03), FMA (0.930 ± 0.05), and FCH (0.94 ± 0.04) varieties have a globose shape (I = 0.9–1.1), which is good for business because it looks good and is easy to present, package, and transportation87,88. Fruit shapes vary based on development stage, cultural maintenance, environmental factors, and genotype24,89.

The width of the figs was found to range from small [28–38 mm] to medium [38–49 mm] at FMA (39.75 ± 1.32 mm), FGD (39.50 ± 3.10 mm), and FBN (41.25 ± 3.18 mm). However, FCH (47.18 ± 3.08 mm) and FOH (47.65 ± 3.55 mm) moved between medium and large [50–60 mm].

The length of the figs is long [54–75 mm] for FOH (64.39 ± 5.10 mm), between medium [29–54 mm] and long for FGD (57.24 ± 5.06 mm), medium for FCH (50.19 ± 2.75 mm), FBN (44.83 ± 2.85 mm), and FMA (42.74 ± 1.18 mm)2.

The findings indicate that the weight of figs is substantial in FOH (57.25 ± 8.24 g) and FCH (50.32 ± 6.15 g), moderate for FGD (43.56 ± 4.65 g), and FBN (41.09 ± 3.35 g). In contrast, FMA exhibited the lowest weight (30.24 ± 1.52 g). The results of the standard one-way ANOVA with a threshold of 5% show that the differences are significant between all varieties except FGD and FBN. The weight of figs provides very beneficial pricing to producers and market traders; hence, FOH, FCH, and FGD will surely have the best marketing opportunities, and as a result, their quality will be valued by consumers23.

The FOH variety has the longest neck (12.75 ± 2.05 mm), followed by the FCH, FGD, FMA, and FBN varieties (4.85 ± 0.15) in that order. The ANOVA analysis of neck length, using a significance threshold of 5%, indicates that there are significant differences across the varieties, except for FGD, FMA, and FBN. Arborists consider short necks to be an undesirable quality in contrast to lengthy stalks, as they impede fruit harvesting and cause damage to the fruit. The difficulty of harvesting short-necked varieties like FBN and FMA may deter growers. Conversely, cultivars with long necks and stalks, like FOH, offer the advantage of being easier to harvest23.

The study found that FOH figs (6.88 ± 1.08 mm) have the widest ostiol, followed by FCH, FGD, FBN, and FMA (3.80 ± 0.25 mm). The ANOVA (5%) analysis of ostiol width shows significant differences amongst varieties except for FCH, FGD, and FBN. A larger ostiol allows blastophagous insects as well as insecticides and diseases, making cultivars with this characteristic unsuitable for the fig industry or storage25 Figs that have no skin cracks and are simple to peel are regarded as high-quality for fresh consumption23,61.

The study discovered that FOH has the best peelability; FMA has the best skin cracking; and FCH has the worst skin cracking. Low temperatures and excessive humidity during fig ripening exacerbate skin fissures, which are especially common in genotypes with a thin epidermis90. Long-maturing cultivars are susceptible to skin cracking and should not be grown in rainy or early fall conditions. Cracking occurs at the ostiol during ripening, which is exacerbated by low temperatures and/or high relative humidity91.

The highest percentages of total soluble solids (TSS) were FGD (23.16 ± 0.04%) and FOH (23.10 ± 0.08%), followed by FBN, FCH, and FMA (16.04 ± 0.02%). Except for FGD and FOH, the ANOVA at 5% for TSS shows significant variations among varieties. The increase in total soluble sugars (TSS) in fig fruits may be attributable to the conversion of stored starch and other insoluble carbohydrates into soluble sugars. This is due to the climacteric nature of figs, which is characterized by the production of ethylene gas during ripening, resulting in fruit softening and sugar being released92,93. In terms of titratable acidity (TA), FCH has the highest percentage (0.272 ± 0.03% C.A = Citric Acid), followed by FBN, FMA, FGD, and FOH (0.245 ± 0.01% C.A). At 5%, the ANOVA test of TA reveals no significant variations across varieties. The concentration of organic acids in the fruit is a critical determinant of its flavor formation. The pulp and peel of figs contain many acids, including malic acid, citric acid, ascorbic acid, succinic acid, shikimic acid, tartaric acid, fumaric acid, and oxalic acid. Among these, malic and citric acids are the main components found in the pulp, while malic and oxalic acids are the most common in the peel6,40,94. Organic acids represent the primary source of acidity in fruits and vegetables, with higher concentrations being essential for effective metabolic pathways. The process of maturation and ripening is accompanied by a loss of acidity, largely attributable to the utilization of these acids as a substrate for respiration, which subsequently leads to their conversion into sugars95. In biological processes, organic acids are involved as intermediates or end products in many important pathways of metabolism and catabolism in animals and plants, and play a major role in the tricarboxylic acid or citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle), a vital pathway in eukaryotes and the primary source of electrons for the mitochondrial respiratory membrane96. These compounds are found in all organisms. However, plants have a unique ability to accumulate organic acids in cellular reactions. Organic acids influence the organoleptic properties of fruits and vegetables, such as color, flavor, and aroma96.

TSS and TA are two important chemical traits of fresh fruit that are used to determine its quality and to tell the difference between varieties. For fresh figs, the best score for TSS is between 16.1% and 20.0%, which was the case for FCH. For TA, the best score is between 0.226 and 0.30%, which was the case for all the varieties that were studied. All examined varieties meet the standards for high-quality fresh fig fruit, with TSS concentrations ranging from 13.0 to 25.1% and TA values between 0.226 and 0.30%97.

The TSS/TA ratio is one of the main characteristics that determine fruit flavor and texture. It is what gives many fruits their characteristic flavor. It is also an indicator of commercial and consumer ripeness. Therefore, the variety ‘MA’ had the lowest TSS/TA ratio at 64.41, while ‘OH’ had the highest ratio at 94.28, followed by ‘GD’, BN, and CH. As reported by Crisosto et al., the TSS/TA values for four ripe fig varieties vary from 46.5 for Calimyrna to 86.1 for Kadota. Cultivar, maturity stage, and the interaction between the two factors all had an impact on TSS/TA98. Brix value and acidity, as well as the brix-acidity ratio are the common quality indicators used to determine sweetness, tartness of a fruit juice, and degree of maturity of the fruits from which the juice was extracted, respectively. High brix value indicates high sugar content as well as high in amino acids; minerals, organic acids and other water soluble components whereas high titratable acidity indicates high organic acid contents. A high ratio implies a sweeter taste with balanced acidity, which is desirable in many fruit juices and wines99. Different fruits have ideal Brix/Acid Ratios for optimal taste and marketability, making this measurement essential for quality assurance and product development in the food industry. Brix/acid ratio was found to be the best objective measurement that reflected the consumer acceptability and can be used as a reliable tool to determine the optimum harvesting stage of the fruit100.

The Aksoy weighted ranked method assigns the lowest score to FMA (610) and FBN (640). The highest scores are recorded for FGD (682), followed by FOH (718), and FCH (720). These scores indicate that the pomological quality of the figs in AHFIR is exceptionally high. The genotypic effect, environmental conditions (temperature, humidity, wind, etc.), stage of maturation, and maintenance all impact the quality of fresh figs25.

The outcomes of this study are regarded as highly encouraging, as the Aksoy ranking method conceptualises quality with consideration for the characteristics of the fig and its relationship with the fig grower, the fig seller, and the fruit consumer. From this perspective, there is a compelling rationale for the preservation of fig diversity in eastern Morocco, with a focus on safeguarding it from erosion and, indeed, actively promoting its enrichment and diversification. A comprehensive and in-depth study is imperative to determine the most effective propagation methods for the fig tree and to explore strategies for enhancing its value through the production of derived products that align with its unique characteristics. To this end, it is essential to extend research endeavours and to establish a comprehensive database that will serve as a valuable resource for a range of stakeholders, including but not limited to the food industry and the pharmaceutical sector.

Marketing and quality of dried figs

The moisture content of DCH was higher (25.44 ± 0.24%) than that of DGD (24.25 ± 0.45%); therefore, these two dried figs met the required criteria of ≤ 26.0% for untreated dried figs.

The results show that the dried fig units per kg are 79 ± 1 units per kg for DCH and 85.33 ± 1.52 units per kg for DGD, so they belong to category I. In addition, based on the correlation between the number of units per kg and the corresponding fruit standard (Table 3), DCH has the peculiarity of being almost at the upper limit of code caliber 8; while GD dried figs take the code caliber 9.

Furthermore, the diameter of the DCH as a white Fig. (40.8 ± 2.24 mm) requires a minimum diameter of 22 mm, and the diameter of the DGD as a black Fig. (29.5 ± 1.85 mm) meets the recommended threshold of 18 mm.

Sun-drying of crops is the predominant food preservation technique in many African countries, as the region experiences consistently high levels of solar radiation throughout the year. Sun-drying is a conventional technique for the production of dried figs, requiring minimal investment and simple equipment. It produces figs with excellent flavor and uniform texture. Although other alternative drying techniques have been developed, sun-drying remains a preferred technique for preserving the nutritional integrity of foods101.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA), as seen in Fig. 4, accounts for 95.318% of the overall variance. Specifically, Component 1 explains 81.955% of the variance, while Component 2 explains 13.363%. Component 1 exhibits a high positive correlation with TPC (0.981), followed by Mg, Fe, DF, and lastly TA (0.773). It also shows a strong negative correlation with DPPH IC50 (− 0.982), followed by OW, VitC, and finally weight (− 0.751). Component 2 exhibits a significant positive correlation with Na (0.981), followed by Ca, K, LiC, P, PrC, and TSC (0.729). Conversely, it shows a substantial negative correlation with TFC (− 0.976), followed by TSS (− 0.697).

The regression results indicate a strong negative association between some studied traits and components 1 and 2. Specifically, the two fresh fig varieties, FGD and FCH, are most distinguished by these traits. TFC and TSS are particularly prominent in FGD, while FCH stands out for its high values of IC50, OW, VitC, and weight. Conversely, it is evident that the other analyzed factors, which exhibited a significant positive correlation with components 1 and 2, align with the characteristics of the two dried figs. Specifically, TPC, Mg, Fe, DF, and TA are the most distinguishing attributes for DGD, whereas Na, Ca, K, LiC, P, PrC, and TSC are indicative of DCH.

The impact of sun-drying the two fresh figs were significant. The dried figs exhibited higher levels of macronutrients, titratable acidity, and all the minerals (potassium, sodium, magnesium, calcium, iron, and phosphorus) that were analyzed. Additionally, they demonstrated higher antioxidant activity, as indicated by the total phenolic content (TPC). Conversely, a reduction in the levels of antioxidants (flavonoids) and vitamin C was observed. Vitamin C is also an antioxidant and contributes to the total soluble solids (TSS) content. Furthermore, a notable reduction in weight was observed, which is to be expected given that water constitutes the primary and most abundant component of living cells. Furthermore, a notable reduction in ostiol width was observed, which could be regarded as a beneficial outcome from the perspectives of health, industry, and storage.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA); based on the different traits analyzed in the fresh fig varieties CH and GD and the two dried fig varieties resulting from them after sun drying. FCH, Fresh Chetoui; FGD, Fresh Ghoudane; DCH, Dried Chetoui; DGD, Dried Ghoudane; TPC, Total phenol content; TFC, Total flavonoid content; IC50, DPPH IC50; OW, Ostiol width; vitC, Vitamin C; LiC, Lipid content; PrC, Protein content; DF, Dietary fiber; TSC, Total sugars content; TSS, Total soluble solids; TA, Titratable acidity; Weight, Weight of fresh or dried fig; K, Potassium; Na, Sodium; Ca, Calcium; Mg, Magnesium; Fe, Iron; P, Phosphorus.

Principal component analysis was employed to gain further insight into the relationship between TPC, TFC, and vitamin C and their impact on antioxidant activity, with the DPPH IC50 index serving as the dependent variable. This is the concentration required to achieve a 50% reduction in DPPH radicals. IC50 demonstrates a strong negative correlation with component 1, whereas TPC exhibits a strong direct relationship with it, in contrast to the other analysed antioxidants TFC and vitamin C. TPC demonstrates a clear and robust capacity to scavenge DPPH radicals, thereby illustrating its superiority over the other studied antioxidants.

Conclusion

The present study has expanded the understanding of figs, a fundamental constituent of the Mediterranean diet, through a comprehensive analysis of their nutritional attributes. It is emphasized that the fresh fig varieties cultivated in the AHFIR geographical area meet the fresh fruit market’s requirements for pomological quality, diversity, and maturation distribution. In addition, these fruits function as a reservoir of essential macronutrients, including carbohydrates, dietary fiber, proteins, vitamins, and minerals. These include potassium (K), phosphorus (P), iron (Fe), potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), and calcium (Ca). In addition, they contain an abundance of antioxidants, including phenolic acids, flavonoids, and others, which contribute to their nutritional value and health benefits, thereby increasing consumer acceptance. There is a notable diversity in the content of phytochemicals (TFC, TPC, etc.) not only across different varieties but also among different parts of the fruit and its ripeness and state (fresh or dried). Despite fig peels being the richest source of antioxidants, particularly the dark ones, they are not widely consumed. Therefore, they should be used as a by-product, providing the pharmaceutical and food industries with a vital source of antioxidants and a natural food preservative. Sun-drying represents a viable alternative to the costly and energy-intensive process of artificial technology. It is imperative to ensure the maintenance of nutritional content and suitability by ensuring the appropriate temperature and drying time. The study’s findings underscore the importance of AHFIR dried fig varieties, emphasizing their role not only as a nutritious component of a dietary regimen but also as a source of health-promoting benefits derived from their antimicrobial and antioxidant compounds. Consequently, incorporating dried figs in a nutritionally balanced diet has the potential to yield favorable health outcomes. Given the commercial rating of the two dried fig varieties in this area, it is recommended to utilize them in other products that are better suited to their characteristics in order to enhance their value. Furthermore, the cultivation of trees specifically bred to provide extra-dried fig quality has the potential to enhance the biodiversity of fig trees. It is imperative to ensure that the findings of these investigations are made accessible to the public. This would ensure a broad range of food options and guarantee food safety across diverse geographical regions worldwide.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Pérez-Sánchez, R. & Morales-Corts, R. M. Gómez-Sánchez, Á. M. Agro-morphological diversity of traditional Fig cultivars grown in Central-Western Spain. Genetika 48, 533–546 (2016).

IPGRI, C. Descriptors for fig. International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome, Italy, and International Centre for Advanced Mediterranean Agronomic Studies, Paris, France 52 (2003).

Gil, J., González, A., Morales, J., Perera, J. & Castro, N. Las Higueras Canarias y Su diversidad: bases orales y documentales Para Su estudio. Rincones Del. Atlántico. 3, 250–257 (2006).

Hssaini, L. et al. Assessment of morphological traits and fruit metabolites in eleven Fig varieties (Ficus carica L). Int. J. Fruit Sci. 20, 8–28 (2020).

Kuś, P. M. et al. Antioxidant activity, color characteristics, total phenol content and general HPLC fingerprints of six Polish unifloral honey types. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 55, 124–130 (2014).

Viuda-Martos, M., Barber, X., Pérez-Álvarez, J. A. & Fernández-López, J. Assessment of chemical, physico-chemical, techno-functional and antioxidant properties of Fig (Ficus carica L.) powder co-products. Ind. Crops Prod. 69, 472–479 (2015).

Rodov, V., Vinokur, Y. & Horev, B. Brief postharvest exposure to pulsed light stimulates coloration and anthocyanin accumulation in Fig fruit (Ficus carica L.). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 68, 43–46 (2012).

Sedaghat, S. & Rahemi, M. Effects of physio-chemical changes during fruit development on nutritional quality of Fig (Ficus carica L. var.‘Sabz’) under rain-fed condition. Sci. Hort. 237, 44–50 (2018).

Meziant, L., Saci, F., Bachir Bey, M. & Louaileche, M. Varietal influence on biological properties of Algerian light figs (Ficus carica L). Int. J. Bioinf. Biomed. Eng. 1, 237–243 (2015).

Barolo, M. I., Mostacero, N. R. & López, S. N. Ficus carica L. (Moraceae): an ancient source of food and health. Food Chem. 164, 119–127 (2014).

Veberic, R. & Mikulic-Petkovsek, M. In Nutritional Composition of Fruit Cultivars 235–255 (Elsevier, 2016).

Pourghayoumi, M. et al. Phytochemical attributes of some dried Fig (Ficus carica L.) fruit cultivars grown in Iran. Agriculturae Conspectus Scientificus. 81, 161–166 (2016).

Achtak, H. et al. Traditional agroecosystems as conservatories and incubators of cultivated plant varietal diversity: the case of Fig (Ficus carica L.) in Morocco. BMC Plant Biol. 10, 1–12 (2010).

Hmimsa, Y., Aumeeruddy-Thomas, Y. & Ater, M. Une forme spontanée de figuier (Ficus carica L.), le nābūt. Diversité de nomenclature, d’usage et de pratiques locales au Nord du Maroc. Revue d’ethnoécologie (2017).

Zohary, D. & Hopf, M. Domestication of Plants in the Old World: the Origin and Spread of Cultivated Plants in West Asia, Europe and the Nile Valley (Oxford University Press, 2000).

Khadari, B., Grout, C., Santoni, S. & Kjellberg, F. Contrasted genetic diversity and differentiation among mediterranean populations of Ficus carica L.: a study using MtDNA RFLP. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 52, 97–109 (2005).

Hirst, K. (1996).

Aljane, F. & Ferchichi, A. Postharvest chemical properties and mineral contents of some Fig (Ficus carica L.) cultivars in Tunisia. J. Food Agric. Environ. 7, 209–212 (2009).

Feinberg, M., Laussucq, C., Ireland-Ripert, J. & Favier, J. C. Répertoire général des aliments: fruits exotiques. Répertoire Général Des. Aliments, 1–272 (1993).

Chimi, H., Ouaouich, A., Semmar, M. & Tayebi, S. In III International Symposium on Fig. 798. 331–334.

Faleh, E. et al. Influence of Tunisian Ficus carica fruit variability in phenolic profiles and in vitro radical scavenging potential. Revista Brasileira De Farmacognosia. 22, 1282–1289 (2012).

Stover, E., Aradhya, M., Crisosto, C. & Ferguson, L. In Proceedings of the California Plant and Soil Conference.

Tikent, A. et al. In E3S Web of Conferences. 04008 (EDP Sciences).

Çalişkan, O. & Polat, A. A. Morphological diversity among Fig (Ficus carica L.) accessions sampled from the Eastern mediterranean region of Turkey. Turk. J. Agric. For.. 36, 179–193 (2012).

Gaaliche, B., Trad, M., Hfaiedh, L., Lakhal, W. & Mars, M. Pomological and biochemical characteristics of Fig (Ficus carica L.) Cv. Zidi in different agro-ecological zones of Tunisia. Pak. J. Agric. Sci. 49, 425–428 (2012).

Tikent, A. et al. The antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of two Sun-Dried Fig varieties (Ficus carica L.) produced in Eastern Morocco and the investigation of Pomological, colorimetric, and phytochemical characteristics for improved valorization. Int. J. Plant. Biol.. 14, 845–863 (2023).

Manoj, K., Bornare, D. & Kalyan, B. Effect of drying on physicochemical and nutritional quality of Ficus carica (fig). Int. J. Eng. Res. 7, 117–121 (2018).

Gani, G., Fatima, T., Qadri, T., Beenish Jan, N. & Bashir, O. Phytochemistry and Pharmacological activities of Fig (Ficuscarica): A review. Inter J. Res. Pharm. Pharmaceut Sci. 3, 80–82 (2018).

El Khaloui, M. Valorisation de La Figue Au Maroc. Transfert De Technologie En Agric. (Maroc). 186, 1–4 (2010).

Sies, H. Oxidative stress: oxidants and antioxidants. Exp. Physiol. Transl. Integr. 82, 291–295 (1997).

Kim, M. H. & Choi, M. K. Seven dietary minerals (Ca, P, Mg, Fe, Zn, Cu, and Mn) and their relationship with blood pressure and blood lipids in healthy adults with self-selected diet. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 153, 69–75 (2013).

Calder, P. C., Carr, A. C., Gombart, A. F. & Eggersdorfer, M. Optimal nutritional status for a well-functioning immune system is an important factor to protect against viral infections. Nutrients 12, 1181 (2020).

Maggini, S., Pierre, A. & Calder, P. C. Immune function and micronutrient requirements change over the life course. Nutrients 10, 1531 (2018).

Li, K., Zhang, M., Mujumdar, A. S. & Chitrakar, B. Recent developments in physical field-based drying techniques for fruits and vegetables. Drying Technol. (2019).

Darjazi, B. B. Morphological and Pomological characteristics of Fig (Ficus carica L.) cultivars from Varamin, Iran. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 10, 19096 (2011).

Isa, M., Jaafar, M., Kasim, K. & Mutalib, M. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 012134 (IOP Publishing).

Arya, J. Food Is your Medicine (Dr. Arya, 2014).

Oukabli, A. Le Figuier Un patrimoine génétique diversifié à exploiter. Bull. Mensuel D’information Et De Liaison Du PNTTA 106 (2003).

Rasool, I. F. et al. Industrial application and health prospective of Fig (Ficus carica) by-products. Molecules 28, 960 (2023).

Oliveira, A. P. et al. Ficus carica L.: metabolic and biological screening. Food Chem. Toxicol. 47, 2841–2846 (2009).

Vallejo, F., Marín, J. & Tomás-Barberán, F. A. Phenolic compound content of fresh and dried figs (Ficus carica L.). Food Chem. 130, 485–492 (2012).

Veberic, R., Colaric, M. & Stampar, F. Phenolic acids and flavonoids of Fig fruit (Ficus carica L.) in the Northern mediterranean region. Food Chem. 106, 153–157 (2008).

Hamid, A., Aiyelaagbe, O., Usman, L., Ameen, O. & Lawal, A. Antioxidants: its medicinal and pharmacological applications. Afr. J. Pure Appl. Chem. 4, 142–151 (2010).

Bjelakovic, G., Nikolova, D., Gluud, L. L., Simonetti, R. G. & Gluud, C. Mortality in randomized trials of antioxidant supplements for primary and secondary prevention: systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama 297, 842–857 (2007).

Ćujić, N. et al. Optimization of polyphenols extraction from dried chokeberry using maceration as traditional technique. Food Chem. 194, 135–142 (2016).

Vajić, U. J. et al. Optimization of extraction of stinging nettle leaf phenolic compounds using response surface methodology. Ind. Crops Prod. 74, 912–917 (2015).

Tikent, A. et al. Antioxidant potential, antimicrobial activity, polyphenol profile analysis, and cytotoxicity against breast cancer cell lines of hydroethanolic extracts of leaves of (Ficus carica L.) from Eastern Morocco. Front. Chem. 12, 1505473 .

Do, Q. D. et al. Effect of extraction solvent on total phenol content, total flavonoid content, and antioxidant activity of Limnophila aromatica. J. Food Drug Anal. 22, 296–302 (2014).

Velioglu, Y., Mazza, G., Gao, L. & Oomah, B. Antioxidant activity and total phenolics in selected fruits, vegetables, and grain products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 46, 4113–4117 (1998).

Laaraj, S. et al. Influence of harvesting stage on phytochemical composition, antioxidant, and antidiabetic activity of immature Ceratonia siliqua L. Pulp from Béni Mellal-Khénifra region, Morocco: in Silico, in vitro, and in vivo approaches. Curr. Issues. Mol. Biol. 46, 10991–11020 (2024).

Huang, D. J., Chun-Der, L. & Hsien-Jung, C. & Yaw-Huei, L. Antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas [L.] LamTainong 57’) constituents. Bot. Bull. Acad. Sinica 45 (2004).

Laaraj, S. et al. A study of the bioactive compounds, antioxidant capabilities, antibacterial effectiveness, and cytotoxic effects on breast Cancer cell lines using an ethanolic extract from the aerial parts of the Indigenous plant anabasis aretioïdes Coss. & Moq. Curr. Issues. Mol. Biol. 46, 12375–12396 (2024).

DuBois, M., Gilles, K. A., Hamilton, J. K., Rebers, P. & Smith, F. t. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem.. 28, 350–356 (1956).

Kjeldahl, J. Neue methode Zur bestimmung des stickstoffs in organischen Körpern. Z. Für Analytische Chemie. 22, 366–382 (1883).

Committee, A. A. o. C. C. A. M. (AACC).

Pereira, C. et al. Physicochemical and nutritional characterization of Brebas for fresh consumption from nine Fig varieties (Ficus carica L.) grown in Extremadura (Spain). J. Food Qual. 2017 (2017).

Mau, J. L., Tsai, S. Y., Tseng, Y. H. & Huang, S. J. Antioxidant properties of methanolic extracts from ganoderma Tsugae. Food Chem. 93, 641–649 (2005).

Khan, M. N., Sarwar, A., Adeel, M. & Wahab, M. Nutritional evaluation of Ficus carica Indigenous to Pakistan. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 11, 5187–5202 (2011).

Horwitz, W. Official Methods of Analysis, vol. 222 (Association of Official Analytical Chemists Washington, DC, 1975).

Tyl, C. & Sadler, G. D. pH and titratable acidity. Food Anal.. 389–406 (2017).

Aksoy, U. Descriptors for fig (Ficus carica L. and related Ficus sp.). Ege University, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Horticulture, Izmir-Turkey (1991).

Unies., N. UNECE STANDARD DDP-15 concerning the marketing and control commercial quality of dried Figs. Nations Unies, New York and Genève. (2014).

Solomon, A. et al. Antioxidant activities and anthocyanin content of fresh fruits of common Fig (Ficus carica L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 54, 7717–7723 (2006).

Çalişkan, O. & Polat, A. A. Phytochemical and antioxidant properties of selected Fig (Ficus carica L.) accessions from the Eastern mediterranean region of Turkey. Sci. Hort. 128, 473–478 (2011).

Harzallah, A., Bhouri, A. M., Amri, Z., Soltana, H. & Hammami, M. Phytochemical content and antioxidant activity of different fruit parts juices of three figs (Ficus carica L.) varieties grown in Tunisia. Ind. Crops Prod. 83, 255–267 (2016).

Vuorela, S. Analysis, isolation, and bioactivities of rapeseed phenolics. (2005).

Bakar, M. F. A., Mohamed, M., Rahmat, A. & Fry, J. Phytochemicals and antioxidant activity of different parts of Bambangan (Mangifera pajang) and Tarap (Artocarpus odoratissimus). Food Chem. 113, 479–483 (2009).

Marrelli, M. et al. Changes in the phenolic and lipophilic composition, in the enzyme Inhibition and antiproliferative activity of Ficus carica L. cultivar Dottato fruits during maturation. Food Chem. Toxicol. 50, 726–733 (2012).

Kolesnik, A., Kakhniashvili, T., Zherebin, Y. L., Golubev, V. & Pilipenko, L. Lipids of the fruit of Ficus carica. Chem. Nat. Compd. 22, 394–397 (1986).

Lacroix, M. Variations qualitatives & quantitatives de l’apport en protéines laitières chez l’animal & l’homme: implications métaboliques, Paris, AgroParisTech, (2008).

Kulkarni, A. P. & Aradhya, S. M. Chemical changes and antioxidant activity in pomegranate arils during fruit development. Food Chem. 93, 319–324 (2005).

Frenkel, C., Klein, I. & Dilley, D. Protein synthesis in relation to ripening of pome fruits. Plant Physiol. 43, 1146–1153 (1968).

Anderson, J. W. Dietary fiber and human health. HortScience 25, 1488–1495 (1990).

Jiang, L. et al. Noninvasive evaluation of Fructose, glucose, and sucrose contents in Fig fruits during development using chlorophyll fluorescence and chemometrics. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 15, 333–342 (2013).