Abstract

This study developed a self-healing, anti-corrosive coating based on a novel nanocomposite formulation of 8-hydroxyquinoline-5-sulfonic acid-zinc doped polyaniline (HQZn-PA) incorporated into an epoxy matrix. The chemical composition and surface morphology of the synthesized nanocomposite were thoroughly characterized using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, nuclear magnetic resonance, and scanning electron microscopy. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and potentiodynamic polarization tests confirmed the outstanding corrosion resistance and self-healing efficiency of the coating. The synthesized HQZn-PA demonstrates enhanced anticorrosive properties through the synergistic effects of its constituents. Polyaniline (PA) contributes anodic protection and forms a barrier layer, while the chelation of zinc by 8-hydroxyquinoline-5-sulfonic acid (HQZn) improves PA compatibility within the polymer matrix and functions as an organic corrosion inhibitor. This dual action strengthens corrosion resistance through both anodic and cathodic protection mechanisms. The HQZn-PA nanocomposite reduced the corrosion rate of epoxy coating by 450× compared and maintained an impedance modulus of 1.03 × 1010 Ω cm2 after 40 days in a saline environment. The nanocomposite also demonstrated a self-healing efficiency of 99.28% in scratched coatings. These results highlight the potential of HQZn-PA as a highly effective corrosion inhibitor and self-healing agent for long-term metal protection in harsh environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metals, valued for their prolonged durability and exceptional mechanical properties, find indispensable applications across diverse sectors, including oil and gas, marine, aerospace, automobile, railway, bridge, and civil infrastructure. Nonetheless, their susceptibility to corrosion when exposed to environmental elements such as temperature, pressure, water, oxygen, and corrosive solutions can significantly reduce their longevity1. To address these challenges, organic, inorganic, and composite coatings offer a promising solution by forming a protective barrier that shields the metal from its environment, effectively preventing exposure to corrosive agents and hindering corrosion initiation and progression. Among these, epoxy (EP) coatings have gained significant attention due to their exceptional chemical resistance, strong adhesion, hydrophobic nature, and cost effectiveness2. However, despite their effectiveness, conventional anti-corrosion coatings often suffer from inherent defects, such as micropores and crevices that form during the curing process. These structural imperfections can act as pathways for corrosive species, significantly compromising the coating’s integrity and allowing corrosion to initiate at the metal-polymer interface3. As a result, corrosion products accumulate beneath the coating, with anodic and cathodic reactions occurring at the metal-coating interface. The cathodic reaction generates hydroxyl ions (OH⁻), leading to an increase in pH, which subsequently weakens the adhesion of the coating. Hence, ensuring long-term corrosion protection for organic coatings is crucial4.

It has been shown that exploiting a combination of disparate organic and inorganic corrosion inhibitors, as well as conducting polymers, could remarkably tackle the aforementioned challenges5,6,7,8. For instance, studies have demonstrated that polyaniline (PA), in addition to enhancing the barrier properties of organic coatings, can endow applied coatings with a self-healing property owing to its electrochemical characteristics9. Extensive research has demonstrated that PA can enhance the corrosion resistance of steel substrates through various mechanisms, including anodic protection, barrier formation, corrosion inhibition, and modulation of the electrochemical interface10. Among these mechanisms, the primary protective effect is thought to result from the reduction of PA’s emeraldine salt (ES) to its leucoemeraldine base (LB), facilitating Fe oxidation and the formation of a dense protective γ-Fe2O3/Fe3O4 film. In the presence of sufficient oxygen, the LB form can be re-oxidized to ES, providing self-healing properties to the oxide film5. Recognizing these benefits, numerous studies have investigated PA’s role as a nanofiller within highly crosslinked polymers, such as epoxy resins10,11,12,13,14,15.

However, a major challenge limiting the practical application of polyaniline (PA)-based coatings is their poor dispersion and aggregation tendency within the host polymer matrix, which adversely affects their protective performance. Studies have shown that introducing suitable doping agents into PA can significantly improve the corrosion resistance of these coatings. This enhancement is achieved by increasing the compatibility between PA and the host polymer while improving the dispersion of the conductive polymer. For example, phytic acid, used as a dopant, has been shown to greatly enhance the compatibility of PA with epoxy resin. In a study by Hao et al.16 it was observed that coatings containing phytic acid-doped PA provided superior corrosion protection for carbon steel, largely due to the improved compatibility and dispersion of PA within the epoxy matrix. Similarly, PA composites doped with dodecylbenzene sulfonic acid (DBSA) demonstrated improved distribution and interaction within the host matrix, leading to enhanced barrier properties and corrosion resistance. These enhancements result from the doping agent’s ability to stabilize PA’s conductive structure and reduce aggregation17. Gharieh et al.5 demonstrated that incorporating only 2 wt% PA nanofibers into a UV-curable coating matrix reduced the corrosion rate by over two orders of magnitude compared to the neat polymer coating. In another study, Crespy et al.18 developed an anti-corrosion additive utilizing 8-hydroxyquinoline to enhance the anti-corrosive properties of epoxy coatings. They found that the controlled release of corrosion inhibitors significantly improved the anti-corrosion performance of the applied coatings. Furthermore, Zhao et al. demonstrated that the incorporation of melamine resin spheres enhanced structural integrity and mechanical strength, while graphene oxide improved the barrier properties against corrosive agents. This synergistic combination resulted in a robust coating that effectively protected the underlying steel from corrosion, thereby extending the lifespan and reliability of the components19.

Despite these advancements, existing research has primarily focused on single-component approaches, which lack synergistic strategies that combine organic and inorganic inhibitors with conductive polymers to achieve optimal corrosion resistance and self-healing properties. Inorganic corrosion inhibitors, such as zinc and cerium cations, actively reduce the corrosion rate of mild steel by forming an insoluble, integrated layer of metal hydroxides on the metal surface20. For instance, sulfonated polyaniline (SPANi) incorporated into zinc-rich epoxy coatings has demonstrated improved corrosion resistance by enhancing conductivity and stabilizing zinc within the matrix21. Zinc ions, in particular, can integrate with the PA polymer chain, enhancing electron mobility within the polymer matrix. This improvement in charge transfer across the polymer structure is critical for sustaining PA’s capacity to form a protective passive layer on metal surfaces. Enhanced conductivity also enables PA to act as an anodic inhibitor, reducing corrosion rates by swiftly neutralizing oxidizing agents at the metal interface21,22,23.

In this study, a novel multifunctional nanocomposite comprising 8-hydroxyquinoline-5-sulfonic acid-zinc-doped polyaniline (HQZn-PA) was designed to exhibit distinct anti-corrosion and self-healing properties. Each component within this purposefully designed anti-corrosive system played a pivotal role in enhancing the performance of the polymeric coatings. Zinc cations provided cathodic protection, while PA functioned as a self-redox conducting polymer, forming a protective layer. Additionally, 8-hydroxyquinoline-5-sulfonic acid served both as a doping agent, enhancing compatibility, and as an organic corrosion inhibitor, improving the self-healing capability of the epoxy coating. The synergistic combination of these components is anticipated to significantly enhance the corrosion protection performance of the nanocomposite coating compared to a pure polymer coating.

Experimental

The study sourced its raw materials from diverse suppliers, with Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. supplying aniline, zinc chloride (ZnCl2), and 8-hydroxyquinoline-5-sulfonic acid (HQS), while Merck supplied potassium hydroxide (KOH), ammonium persulfate (APS), methanol (CH3OH), ethanol (C2H5OH), and hydrochloric acid (HCl). EPON™ 828 and EPIKURE™ curing agent F205 were purchased from Hexion. The substrate consisted of Q235 steel plates precision-cut to dimensions of 20 mm × 20 mm × 1 mm.

Characterization

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) and 1H-NMR spectroscopy (using a BRUKER-IFS 48 spectrophotometer and a Bruker Avance II instrument operating at 500 MHz, respectively) were employed for the chemical characterization of HQZn and the HQZn-PA nanocomposite, using KBr pellets. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses were conducted on PA, HQZn, and the HQZn-PA nanocomposite using a Philips PW 3710 XRD instrument at 30 kV and 35 mA, with Cu Kα radiation. The morphological examination of the HQZn-PA nanocomposite was performed using field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM), with a Vega II instrument from the Czech Republic. The corrosion protection efficiency of both the solution phase and the coatings was investigated using Potentiodynamic Polarization Curve (PPC) and Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) with an Ivium Vertex instrument. The tests were conducted in accordance with ASTM G59/G102 standards at room temperature in a 3.5% NaCl solution. A three-electrode configuration was employed, consisting of a saturated Ag/AgCl reference electrode, a platinum counter electrode, and a coated steel working electrode. To ensure accuracy, all electrodes were meticulously cleaned before testing. The EIS test frequency ranged from 105 to 10−1 Hz, with a disturbance signal of 5 mV. For the solution phase investigation, 0.1 g of the prepared anti-corrosive pigments were added to 100 mL of saline solution, stirred at room temperature for 24 h, and the resulting extracts were utilized in electrochemical assays. For all anti-corrosion assessments, a steel plate with an exposed surface area of 1 cm2 was immersed in the extract solution, followed by EIS analysis at various immersion durations. PPC and EIS were also used to evaluate the self-healing capability of scratched coatings (1 cm in length and 20 μm in width), comparing the results with neat polymer coatings. All measurements were meticulously performed in triplicate, and the selection of fitting models was conducted by considering multiple options to ensure the most accurate fit.

Synthesis of HQZn

HQZn molecules were synthesized using the following method: 9.76 g (0.0433 mol) of HQS and 1.36 g (0.0099 mol) of ZnCl2 were dissolved in 50 mL of deionized water. The pH of the solution was adjusted to approximately 9 by adding 2 mL of 1 mol/L KOH solution. The reaction mixture was then heated to 60 °C and maintained at this temperature for 30 min. Upon cooling, the resulting yellow HQZn precipitate was isolated via centrifugation and subsequently washed with methanol. Finally, the precipitate was dried in an oven at 50°C for 24 h.

Synthesis of HQZn-PA nanocomposite

Two mL (0.0219 mol) of aniline was mixed with 1 g of the synthesized HQZn in 150 mL of distilled water at 40 °C using ultrasonication, followed by magnetic stirring for 1 h. Polymerization was initiated by the gradual addition of 30 mL of a 15 wt% APS aqueous solution over a 30-min period, with continuous stirring for 7 h at – 5 °C. Finally, the green precipitate of the HQZn-PA nanocomposite was obtained through centrifugation and filtration of the solution. This precipitate was subsequently washed with CH3OH and distilled water and dried at 45 °C for 24 h. Chloride-doped PA (CPA) composites were synthesized using the same procedure, with HQZn replaced by an equivalent quantity of HCl.

Fabrication of nanocomposite coatings

Anti-corrosive coatings were prepared by dispersing 0.076 g of the synthesized anti-corrosive pigments into 5 g of epoxy resin using ultrasonication (150 W, 37 kHz, Adeeco Co.) for 15 min. Subsequently, 2.5 g of hardener was added and slowly mixed with a spatula to obtain a homogeneous mixture. The prepared nanocomposite mixtures, containing 1 wt% anti-corrosive pigment, were uniformly applied to the surface of the steel plate using a film applicator, achieving a wet thickness of 60 ± 5 µm. Finally, the crosslinking reaction was completed through a two-step curing process: first at 25 °C for 8 h, followed by 80 °C for an additional 2 h, with a ramp rate of 10 °C/min. The prepared coatings were labeled as shown in Table 1.

Results and discussion

Characterization HQZn-PA

The chemical composition of the prepared anti-corrosive pigment was evaluated using various techniques. Figure 1a presents the FTIR spectra of CPA, HQZn, and HQZn-PA. In the CPA spectrum, the peaks observed at 1482 cm⁻1 and 1557 cm⁻1 correspond to the stretching vibrations of the benzenoid and quinonoid rings, respectively, indicating the formation of conjugated structures5. The peak at 1293 cm⁻1 is attributed to C–N stretching in the aromatic amine, while the peak at 1237 cm⁻1 suggests the presence of PA in its protonated state24. The peaks at 1128 cm⁻1 and 803 cm⁻1 correspond to the in-plane and out-of-plane bending vibrations of the aromatic C–H bond within the 1,4-disubstituted aromatic ring, respectively. Additionally, the broad band at 3440 cm⁻1 corresponds to the stretching vibration of the H–N–H group5. In the HQZn spectrum, a characteristic absorption peak is observed at 3426 cm⁻1, attributed to the O–H stretching vibration of water molecules in the hydrated state. The peaks at 1610 cm⁻1 and 1504 cm⁻1 correspond to the pyridyl and phenyl groups of 8-hydroxyquinoline-5-sulfonic acid. Furthermore, absorption peaks within the 400–600 cm⁻1 range are associated with the conjugation between metal ions and the attached ligands, specifically Zn–O and Zn–N bonds25. For the HQZn-PA anti-corrosive pigment, the characteristic absorption peaks of both CPA and HQZn are sequentially observed in the FTIR spectrum, confirming the successful synthesis of HQZn-doped PA.

Figure 1b presents the XRD patterns for CPA, HQZn, and PA-HQZn. The pattern for CPA shows distinct peaks at 2θ values of 19.66° and 21.9°, corresponding to the 100 planes of quinoid units and the 110 planes of benzenoid units, respectively. These peaks indicate partial periodicity due to π–π stacking interactions26. HQZn displays a more complex XRD pattern with The XRD pattern of HQZn shows more complexity, with characteristic peaks at 2θ values of 10.66° (023), 18.16° (111), 20.32° (121), 22.24° (112), 24.58° (002), and 27.76° (332)27,28. These pronounced diffraction peaks confirm the high crystallinity of the prepared HQZn complex29,30,31. In the XRD pattern of the HQZn-PA, the peaks are less defined and exhibit lower intensity compared to those of pure HQZn, suggesting a structural interaction between polyaniline and HQZn. Notably, several peaks show a shift of approximately ± 0.5°, indicating the interaction of polyaniline with HQZn. This interaction is likely due to HQZn acting as a dopant for polyaniline, causing changes in the polymer’s morphology. While polyaniline alone is generally amorphous, the HQZn-PA composite exhibits semi-crystalline properties, highlighting the influence of HQZn on the polymer matrix32,33.

The 1H NMR spectrum of HQZn-PA, shown in Fig. 1c, reveals three distinct and evenly spaced peaks at chemical shifts of 6.98 ppm, 7.11 ppm, and 7.24 ppm (Hb), which serve as a clear indicator of the proton attached to nitrogen34. This phenomenon arises due to the presence of 15N, which has a natural abundance of 99.62% and a spin quantum number IN = 1 (while IC = 0). As a result, the proton linked to nitrogen exhibits a triplet pattern in the 1H NMR spectrum35. The distinctive peaks observed at 7.54 and 7.96 ppm (Ha and Hg) correspond to the resonance of aromatic protons attached to the nitrogen in the N–H group. Furthermore, the peaks observed at 9.36, 8.44, 8.05, and 7.28 ppm (He, Hc, Hd, Hf, and Ha, respectively) were attributed to the aromatic hydrogens present in HQS. These findings validate that HQZn effectively participates in the polymerization process by doping the PA chains.

The SEM images of the prepared HQZn (Fig. 2a,b) reveal a rod-like morphology with diameters ranging from 2.5 to 5 µm and lengths of approximately 5–20 µm. The coordination environment surrounding the zinc ions, along with their interaction with hydroxyquinoline ligands, is believed to facilitate anisotropic growth, leading to the formation of these elongated structures36. In contrast, the SEM analysis of the synthesized CPA (Fig. 2c,d) exhibits a distinctive cauliflower-like morphology, characterized by numerous aggregated particles. It is well-known that dopants can affect the nucleation and growth rates during polymerization32. Thus, the observed structure is likely influenced by the presence of chlorine as a dopant, altering the nucleation and growth patterns of the PA chains and promoting the formation of such cauliflower-like structures.

The SEM image of the HQZn-PA nanocomposite (Fig. 2e,f) presents a more granular and less aggregated morphology, featuring smoother surfaces and a more uniform particle distribution, with particle diameters in the range of 16–20 nm. It seems that the HQZn dopant provides a more controlled growth environment, leading to a distinct structural arrangement. In other words, the HQZn dopant introduces different ionic interactions and steric effects compared to chlorine, promoting a more orderly arrangement of PA chains and contributing to the smoother and more uniform morphology.

It is suggested that the granular and less aggregated morphology of HQZn-PA, as observed in SEM images, allows for better dispersion within the epoxy resin, ensuring a more homogeneous distribution of the anti-corrosive agent throughout the coating. Additionally, the uniform and less porous morphology minimizes the presence of defects and voids within the coating, providing a more effective barrier against corrosive agents. Furthermore, the elemental mapping images (Fig. 2g,k) confirm the presence of 22.35 wt% sulfur (S), 7.35 wt% nitrogen (N), 1 wt% zinc (Zn), and 13.36 wt% oxygen (O). These findings indicate that the HQZn-PA anti-corrosive pigment could be successfully fabricated by employing the synthesized HQZn doping agent during the chemical polymerization of aniline.

Investigation of anti-corrosive effectiveness

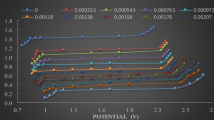

To assess the effectiveness of the synthesized nanocomposite in mitigating corrosion reactions and demonstrating anti-corrosive attributes, steel specimens were immersed in saline solutions, both with and without HQZn-PA extracts. Figure 3 shows the obtained Nyquist and Bode plots of the submerged specimens. Additionally, the electrochemical data underwent rigorous examination employing equivalent circuit (EQC) models, featuring one-time and two-time constants as inserted in Fig. 3b,d, respectively. The resultant parameters derived from EQC models are meticulously outlined in Table 2.

In the realm of electrochemical analysis, the parameters Rs, Rf, and Rct delineate the resistance of the solution, the established passive layer, and the charge transfer, respectively. Rather than employing ideal capacitors, CPEdl and CPEf are utilized to represent the constant phase elements of the double layer and the formed passive layer, respectively. These constant phase elements integrate parameters such as admittance (Y0) and constants associated with surface inhomogeneity (n). For steel samples immersed in a saline solution, impedance diagrams were fitted using a one-time constant model, indicating a charge transfer mechanism37. Noteworthy are the discerned results (Table 2), which revealed subtle fluctuations in Rct over time. Such variations are likely attributed to the formation of a porous and delicate protective layer comprising iron oxide/hydroxide, along with the infiltration of corrosive ions. The marginal increase of |Z|0.1Hz values observed in the solution containing CPA extract, compared to the pure salt solution, can be attributed to the presence of PA and the consequent formation of an inhibitory layer composed of metal oxide. Nonetheless, the protective film that formed on the steel surface was insufficiently dense to provide effective corrosion resistance27,35. In contrast, the EIS results of steel samples immersed for 48 h in the saline solution of HQZn-PA extract were fitted using a two-time constant EQC model. The obtained parameters from this model are shown in Table 2. The observed rise in Rf values from 98 to 141 Ω cm2 with increasing immersion time, coupled with the widening of the phase-log frequency diagram, signifies the augmentation of the resistance offered by the passive layer formed on the metal surface28. Additionally, the increase in the value of impedance at low frequency (|Z|0.1Hz) for the immersed steel in the HQZn-PA extract, unequivocally underscores the efficacy of the synthesized nanostructure in mitigating corrosion reactions on the surface of the immersed steel plate5.

PPCs presented in Fig. 4a were used to evaluate the inhibition mechanisms of different samples after 48 h of immersion in saline solutions, both with and without the addition of HQZn-PA extract. The derived values of corrosion current density (Icorr), corrosion potential (Ecorr), anodic branch slope (βa), cathodic branch slope (βc), and corrosion rate (CR) from obtained PPCs were presented in Table 3. The corrosion rate (CR) was calculated in accordance with ASTM G102-89, using Eq. (1)26,38,39.

Here, the symbol K represents a value of 3268.5 (mol/A), M denotes the molecular weight of iron (56 g/mol), D signifies the density of iron (7.85 g/cm3), V represents the valence of iron, and Icorr denotes the corrosion current densities of the samples.

In comparison with immersed steel plates in neat and extracted saline solutions, the lower Icorr and higher Ecorr for the latter substantiate that the prepared anti-corrosive pigments could effectively form a stable passive layer on the submerged metal surface. Such a phenomenon was more validated by the observed reduction of more than 60% reduction in CR for the immersed sample in HQZn-PA extract, in comparison to the blank saline solution28.

Protection efficiency (Pe) and polarization resistance (Rp) are two key factors that can be used to assess the anticorrosion performance of the prepared extract solutions 5. These parameters were determined using the following equations:

In these equations, I0corr and Icorr represent the corrosion current densities of samples without and with the anti-corrosion film, respectively. The obtained values of Pe and Rp clearly indicate that the HQZn-PA has a significant positive effect on its anticorrosion performance. The outstanding anti-corrosive efficiency of HQZn-PA can be attributed to its dual mechanism of anodic and cathodic protection, which facilitates the formation of a stable passive layer, as illustrated in Fig. 5. Polyaniline (PA), with an electrochemical potential close to that of silver, promotes the development of a dense Fe₃O₄ passive layer by undergoing reduction to its leucoemeraldine base (LB) form. This reduction process generates ferric cations, thereby offering anodic protection to the steel substrate. Concurrently, the reduction of PA releases the HQZn doping agent, which functions as a highly effective anti-corrosive agent. Moreover, cathodic zones are effectively shielded through the formation of zinc hydroxide/oxide, while active anodic sites are mitigated by a protective layer formed by PA and iron-HQS complexes40,41. These combined protection mechanisms, as evidenced by the βa and βc values, confer mixed-type protection and significantly reduce the corrosion rate in steel samples treated with HQZn-PA extracts.

The efficacy of the prepared anti-corrosive pigment was evaluated using SEM images of the steel substrate immersed in HQZn-PA extract. As depicted in Fig. 4b–d, a dense and compact protective layer was developed on the substrate surface after 48 h of immersion, demonstrating its critical role in shielding the metal. Additionally, elemental mapping images (Fig. 4e–i) confirmed the layer’s composition, consisting of 11.62 wt% sulfur (S), 52.4 wt% carbon (C), 13.58 wt% nitrogen (N), 1.92 wt% zinc (Zn), and 20.48 wt% oxygen (O). SEM imaging and elemental mapping (Fig. 4e–i) provided direct visual evidence of the uniform distribution of key elements (Zn, N, S, C, and O), indicating successful adsorption. To further quantify the adsorption efficiency, an EIS analysis was conducted to assess charge transfer resistance and coating capacitance, both of which directly reflect the surface coverage by HQZn-PA.

The anti-corrosion performance of the prepared pigments within the coating structure was evaluated using EIS data from coated steel samples immersed in a 3.5 wt% NaCl solution. Figure 6 presents the Nyquist and Bode plots illustrating the behavior of the coatings submerged in a 3.5 wt% NaCl solution over different immersion durations. Notably, it has been established that the coating’s protective performance directly correlates with the impedance modulus observed at low-frequency regions (|Z|0.1 Hz)5. As shown in Fig. 6a–c, during the first 20 days of immersion period, composite coating samples containing PA consistently exhibited higher |Z|0.1Hz values than the EC coating. This distinctive behavior was particularly pronounced for NC2 demonstrating only a slight decrease in |Z|0.1Hz from 1.49 × 1011 Ω cm2 to 1.03 × 1010 Ω cm2 after 40 days of immersion in a saline solution. Moreover, after 40 days of immersion, the |Z|0.1Hz value for NC4 was one order of magnitude lower than that of NC2, underscoring the significant enhancement in protective properties afforded by the utilization of HQZn compared to the chloride doping agent.

It is well known that an intact and defect-free coating exhibits characteristics analogous to those of a simple capacitor at a given frequency, with its phase angle ideally at 90°42. Hence, phase angle plots serve as a valuable tool for scrutinizing alterations in the internal structure of coatings over time in response to immersion. In the case of the pristine epoxy coating, as depicted in Fig. 6a, the phase angle in the high-frequency region remains relatively stable during the initial days, indicating that the epoxy coating possessing a robust structure capable of protecting the steel substrate from corrosion. However, as immersion time prolongs, water permeation often triggers swelling or delamination of the coating, accompanied by discernible deterioration in phase angle within the high-frequency region43. Conversely, organic coatings containing HQZn-PA exhibit notably high phase angle values in the high-frequency region (Fig. 6a–c), approaching 90°, which underscores HQZn-PA’s pivotal role in preventing corrosion and delaying coating delamination. Despite slight shrinkage over time, HQZn-PA composite coatings maintain a broader range of high phase angles in the mid-to-high frequency regions compared to those of NC4 and EC.

Typically, a larger diameter of the semicircular arc in Nyquist plots correlates with a higher coating resistance (Rc), indicating enhanced barrier properties that limit the diffusion of corrosive substances through the coating and delay their access to the metal-coating interface5,43. Additionally, a solitary capacitive loop signifies the coating’s blocking properties, while the appearance of a second semicircle at low frequencies results from the diffusion of corrosive elements underneath the coating. It is clear that such a diffusion phenomenon is absent in nanocomposite coatings containing PA throughout the entire 40-day immersion period. This indicates that the diffusion pathways for aggressive species remain partially obstructed, thereby preserving the protective function of the composite coatings on the steel substrate. Remarkably, NC2 demonstrates the most pronounced semicircle diameter, indicative of its superior anti-corrosion efficacy compared to other coatings. This underscores the robustness of the composite coating in safeguarding the underlying steel substrate from corrosive attack.

The EIS results revealed a reduction in the coating’s corrosion resistance as the HQZn-PA content increased from 1 to 1.5 wt%. This behavior, as previously discussed, is likely attributable to the aggregation and clustering of HQZn-PA anticorrosive pigments, which create surface defects and channels that facilitate the ingress of electrolytes and corrosive agents. To confirm this hypothesis, SEM analysis was performed on the NC2, and NC3 coatings following 21 days of immersion in a 3.5 wt% NaCl solution (Fig. 7). The SEM micrographs provide a detailed comparison of the coatings’ structural properties. Figures 6a–c illustrate the NC2 coating, which exhibits a uniform, defect-free surface morphology, indicating the effective dispersion of HQZn-PA pigments within the polymer matrix. This distribution not only maintains the structural integrity of the coating but also enhances its anticorrosive performance through the self-healing properties of HQZn-PA. Conversely, Figs. 6d–f depict the NC3 coating’s compromised morphology, characterized by significant pigment agglomeration and surface defects. These structural issues are attributed to excessive HQZn-PA concentrations, which impede proper dispersion and diminish the coating’s protective capabilities. The stark contrast between NC2 and NC3 underscores the critical importance of optimizing pigment concentration to achieve optimal performance.

Also, the obtained EQC model delineates two distinct corrosion states, each offering insight into the underlying mechanisms. The proposed model in Fig. 8a encompasses solution resistance (Rs), non-ideal coating capacitance (Cc), and coating pore resistance (Rc), suggesting a scenario where the corrosive medium does not reach the steel surface. On the other hand, the EQC model shown in Fig. 8b incorporates the charge transfer resistance (Rct) and double-layer capacitance (Cdl), indicative of interfacial reactions occurring at the surface of the coated steel substrate5,40. The margin of error was meticulously constrained to within ± 10%, ensuring robustness in the fitting procedure. The resultant fitting parameters are shown in Table 4.

The findings unequivocally demonstrate a notable enhancement in the barrier properties of the epoxy coating upon the integration of the HQZn-PA nanocomposite, as evidenced by a Rc value of approximately 9.98 × 109 Ω cm2 following a 40-day immersion in a saline solution. The observed increase can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, the enhanced barrier effect exhibited by the coating effectively shields the underlying substrate, thereby mitigating the ingress of corrosive agents. Furthermore, the incorporation of HQZn-PA facilitates a reduction in coating defects, thereby bolstering its overall protective efficacy. Last but not least, despite the anti-corrosive characteristic of PA, the doping agent within the nanocomposite exerts a robust corrosion inhibitory effect when released from the polyaniline chains. Collectively, these mechanisms underscore the efficacy of HQZn-PA nanocomposites as potent corrosion inhibitors.

Self-healing performance of prepared nanocomposite coating

A comprehensive investigation into the self-healing attributes of the prepared nanocomposite coating was obtained from scratched EC and NC2 coated steels immersed in a 3.5 wt% NaCl solution. Figure 9 presents the Bode and Nyquist plots, along with the corresponding equivalent circuit models, for the samples over the immersion period. It can be observed that after 72 h of submerging of the scratched coatings, significant decreases in impedance values were observed, indicating the onset of electrochemical corrosion reactions at the exposed steel surface. For the EC sample, the progressive decline in |Z|0.1Hz continued as the immersion time increased for the scratched coating. This observation can be attributed to the dissolution of the uncoated iron in the presence of aggressive chloride ions. Furthermore, the incorporation of HQZn-PA and CPA nanocomposites into the epoxy resin (Fig. 8b,c) has yielded notable effects on the |Z|0.1Hz, a pivotal metric indicative of the corrosion resistance across diverse coatings. Notably, the NC2 coating demonstrated the highest |Z|0.1Hz, reaching approximately 8.77 × 104 Ω cm2. This elevated value suggests an effective suppression of electrochemical reactions at both cathodic and anodic sites, underlining the coating’s enhanced corrosion protection capabilities44. Moreover, in the case of NC2, the |Z|0.1Hz value increased with extended immersion from 24 to 144 h, which is another clear manifestation for outstanding self-healing capability of the prepared novel HQZn-PA in forming a dense passive layer on the surface of bare steel and suppressing the corrosion reactions. In other words, the corrosive elements could initiate steel corrosion at the scratched area while simultaneously reducing the emeraldine salt (ES) form of HQZn-PA to its leucoemeraldine base (LB) at the adjacent area of the damaged coating. Such reduction can lead to Fe2+ oxidation to Fe3+ and the formation of a Fe2O3 barrier layer on the steel surface, contributing to enhanced low-frequency resistance. In alignment with the formation of this passive layer, the reduction of HQZn-PA also releases the doping agent (HQZn), which facilitates the formation of HQS-Fe3⁺ chelates and an insoluble zinc hydroxide passive layer on the metal surface, thereby augmenting the corrosion resistance of the damaged coating45.

The obtained EIS plots were fitted with EQC Model b (Fig. 8), with fitting parameters detailed in Table 5. Notably, the charge transfer resistance of NC2 (57.48 × 104 Ω cm2) significantly surpasses that of pure polymer coating (0.41 × 104 Ω cm2), indicating the effective passivation and self-healing capability of HQZn-PA nanocomposites. Furthermore, the healing rate (ηeR%) is calculated using Eq. (4)46:

In this equation, Rct0 and Rct denote the charge-transfer resistance of the scratched EC and NC2 samples, respectively, immersed in a 3.5 wt% NaCl solution. The results reveal that, after 144 h of immersion, the coating containing HQZn-PA exhibited an impressive healing rate of 99.28%, highlighting its superior corrosion protection and self-repairing capabilities.

To further investigate the self-healing process of the NC2 sample, SEM and EDS analyses were performed to examine the scratched region following the completion of the EIS test (Fig. 10). As shown in Fig. 9a–c, a distinct layer with a needle-like morphology is observed within the scratch area. Additionally, the presence of corrosion products in minimal quantities in this specific location signifies the effective performance of NC2. The EDS results (Fig. 9d–h) confirm the presence of zinc and sulfur elements in the aforementioned scratch region, further validating the sustained adsorption and protective behavior of HQZn-PA over time. This serves as additional evidence for the formation of a passive layer and the self-healing capability of NC247.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study successfully synthesized and characterized an advanced nanocomposite consisting of 8-hydroxyquinoline-5-sulfonic acid-zinc doped polyaniline (HQZn-PA), which demonstrated remarkable anti-corrosive and self-healing properties when integrated into epoxy coatings. The inclusion of HQZn-PA significantly enhanced the corrosion protection efficiency, showing a 99.28% self-healing capability after 144 h of immersion in a saline solution. This nanocomposite also exhibited superior electrochemical performance compared to conventional coatings, effectively inhibiting both anodic and cathodic corrosion reactions through the formation of a dense protective layer. The synergistic effects of the polyaniline and the zinc-doped complex played a crucial role in improving the coating’s barrier properties and self-repairing capabilities, ensuring long-term protection of metal substrates. These findings open new avenues for the development of smart, sustainable coatings for industrial applications requiring high-performance corrosion resistance and self-healing functionalities.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PA:

-

Polyaniline

- HQS:

-

8-Hydroxyquinoline-5-sulfonic acid

- HQZn:

-

8-Hydroxyquinoline-5-sulfonic acid-zinc

- HQZn-PA:

-

8-Hydroxyquinoline/zinc-doped polyaniline

- CPA:

-

Chloride-doped PA

- FT-IR:

-

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

- XRD:

-

X-ray diffraction

- PPC:

-

Potentiodynamic polarization curve

- EIS:

-

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy

- SEM:

-

Scanning electron microscopy

- FWHM:

-

Full width at half maximum

- NC1/NC2/NC3/NC4:

-

Nanocomposite coating 1/nanocomposite coating 2/nanocomposite coating 3/nanocomposite coating 4

References

Anwar, S. & Li, X. A review of high-quality epoxy resins for corrosion-resistant applications. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 21, 1–20 (2024).

Murtaza, H. et al. Protective and flame-retardant bifunctional epoxy-based nanocomposite coating by intercomponent synergy between modified CaAl-LDH and rGO. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16(10), 13114–13131 (2024).

Dadkhah, S., Gharieh, A. & Khosravi, M. Eco-friendly UV-curable graphene oxide/fluorinated polyurethane acrylate nanocomposite coating with outstanding anti-corrosive performance. Prog. Org. Coat. 186, 108020 (2024).

Tabish, M. et al. Improving the corrosion protection ability of epoxy coating using CaAl LDH intercalated with 2-mercaptobenzothiazole as a pigment on steel substrate. Prog. Org. Coat. 165, 106765 (2022).

Alipour, F., Gharieh, A., Behzadnasab, M. & Omidvar, A. Eco-friendly AMPS-doped polyaniline/urethane-methacrylate coating as a corrosion protection coating: Electrochemical, surface, theoretical, and thermodynamic studies. Langmuir 39(14), 5115–5128 (2023).

Taheri, N., Sarabi, A. A. & Roshan, S. Investigation of intelligent protection and corrosion detection of epoxy-coated St-12 by redox-responsive microcapsules containing dual-functional 8-hydroxyquinoline. Prog. Org. Coat. 172, 107073 (2022).

Rbaa, M. et al. Synthesis and characterization of novel Cu(II) and Zn(II) complexes of 5-{[(2-Hydroxyethyl) sulfanyl] methyl}-8-hydroxyquinoline as effective acid corrosion inhibitor by experimental and computational testings. Chem. Phys. Lett. 754, 137771 (2020).

Mirmohseni, A., Gharieh, A. & Khorasani, M. Waterborne acrylic–polyaniline nanocomposite as antistatic coating: Preparation and characterization. Iran. Polym. J. 25(12), 991–998 (2016).

Sazou, D. & Deshpande, P. P. Conducting polyaniline nanocomposite-based paints for corrosion protection of steel. Chem. Pap. 71, 459–487 (2017).

Gao, F., Mu, J., Bi, Z., Wang, S. & Li, Z. Recent advances of polyaniline composites in anticorrosive coatings: A review. Prog. Org. Coat. 151, 106071 (2021).

Rangel-Olivares, F. R., Arce-Estrada, E. M. & Cabrera-Sierra, R. Synthesis and characterization of polyaniline-based polymer nanocomposites as anti-corrosion coatings. Coatings 11, 653 (2021).

Verma, C. et al. Epoxy resins as anticorrosive polymeric materials: A review. React. Funct. Polym. 156, 104741 (2020).

Sharma, S., Sudhakara, P., Omran, A. A. B., Singh, J. & Ilyas, R. A. Recent trends and developments in conducting polymer nanocomposites for multifunctional applications. Polymers (Basel) 13, 2898 (2021).

Chen, H., Fan, H., Su, N., Hong, R. & Lu, X. Highly hydrophobic polyaniline nanoparticles for anti-corrosion epoxy coatings. Chem. Eng. J. 420, 130540 (2021).

Deyab, M. A. & Mele, G. Polyaniline/Zn-phthalocyanines nanocomposite for protecting zinc electrode in Zn-air battery. J. Power Sour. 443, 227264 (2019).

Hao, Y. et al. Self-healing epoxy coating loaded with phytic acid doped polyaniline nanofibers impregnated with benzotriazole for Q235 carbon steel. Corros. Sci. 151, 175–189 (2019).

Tian, Z. et al. Recent progress in the preparation of polyaniline nanostructures and their applications in anticorrosive coatings. RSC Adv. 4(54), 28195–28208 (2014).

Auepattana-Aumrung, K., Phakkeeree, T. & Crespy, D. Polymer-corrosion inhibitor conjugates as additives for anti-corrosion application. Prog. Org. Coat. 163, 106639 (2022).

Mubeen, M. et al. Heterostructured melamine resin Spheres@ GO reinforced epoxy composite achieving robust corrosion-resistance of Zn–Al–Mg coated steel for automotive applications. Chem. Eng. J. 499, 156070 (2024).

Hosseini, S. A., Shahrabi, T. & Ramezanzadeh, B. Synergistic effect of Black cumin extract and zinc cations on the mild steel corrosion resistance improvement in NaCl solution; Surface and electrochemical explorations. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 654, 130153 (2022).

Yang, F. et al. Anticorrosive behavior of a zinc-rich epoxy coating containing sulfonated polyaniline in 3.5% NaCl solution. RSC Adv. 8(24), 13237–13247 (2018).

Gong, J. et al. Zinc-ion storage mechanism of polyaniline for rechargeable aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Nanomaterials 12(9), 1438 (2022).

Hoang, T. K., Sun, K. E. K. & Chen, P. J. R. A. Corrosion chemistry and protection of zinc & zinc alloys by polymer-containing materials for potential use in rechargeable aqueous batteries. RSC Adv. 5(52), 41677–41691 (2015).

Mažeikienė, R., Niaura, G. & Malinauskas, A. Poly (N-methylaniline) vs. polyaniline: An extended pH range of polaron stability as revealed by Raman spectroelectrochemistry. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 262, 120140 (2021).

Shahedi, Z., Zare, H. & Sediqy, A. Manufacturing of nanoflowers crystal of ZnQ2 by a co-precipitation process and their morphology-dependent luminescence properties. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 32(6), 6843–6854 (2021).

Dadkhah, S. & Gharieh, A. UV-cured acrylated PANI/graphene oxide nanocomposite coating with superior anti-corrosive protection and self-healing abilities. Prog. Org. Coat. 189, 108346 (2024).

Hosseini, S. A., Shahrabi, T. & Ramezanzadeh, B. Synergistic effect of Black cumin extract and zinc cations on the mild steel corrosion resistance improvement in NaCl solution; Surface and electrochemical explorations. Coll. Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 654, 130153 (2022).

Ghaderi, M., SaadatAbadi, A. R., Mahdavian, M. & Haddadi, S. A. pH-sensitive polydopamine–La(III) complex decorated on carbon nanofiber toward on-demand release functioning of epoxy anti-corrosion coating. Langmuir 38(38), 11707–11723 (2022).

Yamaguchi, S., Iida, T. & Matsui, K. Formation of flower-like crystals of tris (8-hydroxyquinoline) aluminum from 8-hydroxyquinoline on anodic porous alumina. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 1 (2017).

Wang, Y. Y. et al. Crystal growth, structure and optical properties of solvated crystalline Tris (8-hydroxyquinoline) aluminum (III)(Alq3). Dyes Pigments 133, 9–15 (2016).

Shahedi, Z., Jafari, M. R. & Zolanvari, A. A. Synthesis of ZnQ2, CaQ2, and CdQ2 for application in OLED: Optical, thermal, and electrical characterizations. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 28, 7313–7319 (2017).

Rafiqi, F. A. & Majid, K. Synthesis, characterization, photophysical, thermal and electrical properties of composite of polyaniline with zinc bis (8-hydroxyquinolate): A potent composite for electronic and optoelectronic use. RSC Adv. 6(26), 22016–22025 (2016).

Muniz, F. T. L. et al. The Scherrer equation and the dynamical theory of X-ray diffraction. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A: Found. Adv. 72(3), 385–390 (2016).

Wang, X. et al. 1H NMR determination of the doping level of doped polyaniline. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 211(16), 1814–1819 (2010).

Ning, Y. C. Structural Identification of Organic Compounds and Organic Spectroscopy (Publishing Company of Science, Beijing, 2000).

Pan, H.-C. et al. Highly luminescent zinc(II)−Bis (8-hydroxyquinoline) complex nanorods: Sonochemical synthesis, characterizations, and protein sensing. J. Phys. Chem. B 111(20), 5767–5772 (2007).

Mohammadkhani, R., Ramezanzadeh, M., Fedel, M., Ramezanzadeh, B. & Mahdavian, M. PO43–-Loaded ZIF-8-type metal-organic framework-decorated multiwalled carbon nanotube synthesis and application in silane coatings for achieving a smart corrosion protection performance. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 61(32), 11747–11765 (2022).

Liu, Q. et al. Investigation of the anticorrosion properties of graphene oxide doped thin organic anticorrosion films for hot-dip galvanized steel. Appl. Surf. Sci. 480, 646–654 (2019).

Christopher, G., Anbu Kulandainathan, M. & Harichandran, G. Comparative study of effect of corrosion on mild steel with waterborne polyurethane dispersion containing graphene oxide versus carbon black nanocomposites. Prog. Org. Coat. 89, 199–211 (2015).

Auepattana-Aumrung, K. & Crespy, D. Self-healing and anti-corrosion coatings based on responsive polymers with metal coordination bonds. Chem. Eng. J. 452, 139055 (2023).

Yu, H. et al. Electrostatic self-assembly of Zn3(PO4)2/GO composite with improved anti-corrosive properties of water-borne epoxy coating. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 119, 108015 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Self-aligned graphene as anti-corrosive barrier in waterborne polyurethane composite coatings. J. Mater. Chem. A 2(34), 14139–14145 (2014).

Zhou, Z. et al. Enhanced hydrophobicity and barrier property of anti-corrosive coatings with silicified polyaniline filler. Coll. Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 645, 128848 (2022).

Najmi, P. et al. Synthesis and application of Zn-doped polyaniline modified multi-walled carbon nanotubes as stimuli-responsive nanocarrier in the epoxy matrix for achieving excellent barrier-self-healing corrosion protection potency. Chem. Eng. J. 412, 128637 (2021).

Kaghazchi, L., Naderi, R. & Ramezanzadeh, B. Construction of a high-performance anti-corrosion film based on the green tannic acid molecules and zinc cations on steel: Electrochemical/surface investigations. Constr. Build. Mater. 262, 120861 (2020).

Cao, L., Wang, Q., Wang, W., Li, Q. & Chen, S. Synthesis of smart nanofiber coatings with autonomous self-warning and self-healing functions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14(23), 27168–27176 (2022).

Taheri, N. N., Ramezanzadeh, B. & Mahdavian, M. Application of layer-by-layer assembled graphene oxide nanosheets/polyaniline/zinc cations for construction of an effective epoxy coating anti-corrosion system. J. Alloys Compd. 800, 532–549 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the support from the University of Isfahan Research Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ali Gharieh: Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Shakiba Dadkhah: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Ako Sharifian: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gharieh, A., Sharifian, A. & Dadkhah, S. Enhanced long-term corrosion resistance and self-healing of epoxy coating with HQ-Zn-PA nanocomposite. Sci Rep 15, 8154 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92158-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92158-7