Abstract

The Midyan Peninsula between the northern Red Sea and Gulf of Aqaba is the only place along the Red Sea where Lower to Middle Miocene syn-rift sedimentary strata (Aquitanian to Langhian) are continuously exposed, including exceptionally preserved carbonate platforms. We selected four focus areas onshore and one offshore in the Duba Basin to explore the variations in platform morphology, structural setting, spatial distribution, and carbonate factory in the northeast Red Sea. By integrating surface observations, geophysical and well data, and strontium (Sr) isotope stratigraphy, we situate these platforms in the tectonic and paleogeographic context of the opening of the northeastern Red Sea rifted margin. The findings document a transition from mollusk-dominated ramps in the early syn-rift stage (~ 23–21 Ma) to coral- and algal-dominated fringing platforms on normal fault footwalls and delta-top platforms during the rift climax and late syn-rift stages (~ 21–14 Ma). Carbonate production ceased during the Middle to Upper Miocene (~ 13–6 Ma), likely due to very high salinity conditions. New dating indicates that carbonate production resumed at the end of the Miocene (~ 5.5 Ma). Thick, aggrading coral-algal platforms—attached and detached—developed, with their morphology strongly shaped by salt tectonics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The fragmentation of the Tethys Ocean during the Oligocene-Miocene resulted in significant reorganizations of ocean circulation and global climate, thereby driving the expansion of coral reefs in the three main reef provinces of the Mediterranean, Caribbean, and Indo-Pacific during the Miocene1. The simultaneous opening of the Red Sea, caused by the collision between the Africa-Arabia and Eurasia plates2, led to the progressive closure of the Indian Ocean-Mediterranean seaway (IOMS)3while the Red Sea basin was to be flooded by three successive oceans4: the Neo-Tethys Ocean in the early Miocene, the proto-Mediterranean Sea in the middle Miocene and the Indian Ocean from the late Miocene onwards (Fig. 1). Consequently, it is a pivotal region for comprehending the evolution of coral-dominated carbonate systems and their interactions with the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum (MMCO)5during the closure of the IOMS. Furthermore, as one of the youngest oceanic basins on Earth6, the Red Sea also serves as a natural laboratory for exploring the interaction between the development of carbonate platforms and the tectonic evolution of a rifted margin, from continental rifting to oceanic spreading.

Today, the Red Sea is one of the most prolific carbonate provinces worldwide, displaying various modern carbonate platform morphotypes, including offshore bank, delta-top, fault-block, and diapir platforms7,8,9. Additionally, the Miocene platforms exposed along the Egyptian coast are archetypal examples of fault-block platforms in an active rift setting7,10. Previous studies have focused on field and remote-sensing observations to characterize modern and ancient carbonate systems9,11,12,13,14,15; however, integrating subsurface data with refined age constraints remains critical to fully understanding their morphological and associated biota evolution in a more comprehensive spatial and temporal geological framework.

This study focuses on the Midyan Peninsula region in Saudi Arabia between the Gulf of Aqaba and the northern Red Sea, which has experienced partial tectonic inversion due to strike-slip tectonics and the uplift of the eastern margin of the Gulf of Aqaba16,17. Its unique tectonic setting exposes the syn-rift sedimentary series, providing access to a complete succession of ancient carbonate systems and serving as a remarkable geological archive of the regional history in a relatively narrow area of ~ 5000 km². Integrating the surface and subsurface data with the strontium (Sr) isotope stratigraphy enables documenting the spatial and temporal variations in platform morphology, distribution, and ecology throughout the tectonostratigraphic evolution of the northeast Red Sea rifted margin.

Background

The morphologies of modern carbonate platforms bordering the Red Sea include fringing reefs, broader attached and detached platforms, and atolls8,15. These varied morphologies are regarded to be primarily controlled by rift tectonics, siliciclastic input, and salt diapirs8,9,15,18. Recent studies have also highlighted the significant role of thin-skin salt tectonics in shaping modern platform morphologies19,20.

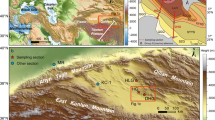

Miocene carbonate platforms outcrop from the coastal plains of the northern Red Sea and Gulf of Suez along structural highs and normal fault escarpments (Fig. 1a, b). These platforms have been extensively described in the Gulf of Suez and along the Egyptian margin of the Red Sea11,14,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. They were also described further south in Sudan22,34and along the Arabian conjugate margin of the Red Sea in Saudi Arabia12,13,35,36,37,38,39,40,41. These studies revealed highly diverse morphologies, including fringing morphologies, delta-topped platforms, and ramps.

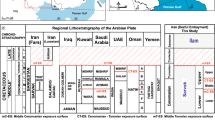

Paleogeographic maps of the locations and references of Miocene and Pliocene carbonate platform outcrops along the conjugate margins of the Red Sea and Gulf of Suez. The palinspastic restoration of the plates, extent of the sea, and seaway locations are adapted from Baby et al.4

Three periods of carbonate platform development are recognized: the Early Miocene (Aquitanian), Middle Miocene (Langhian to Serravallian), and the Pliocene onward (Fig. 1). Bosworth et al21. observed “an apparent relationship between the timing of platform development and the evolution of fault systems within the rift basin” and proposed that the Red Sea and Gulf of Suez carbonate platforms formed during periods of relative tectonic quiescence.

The regional paleogeography of the basin has significantly influenced the development and distribution of carbonate platforms in addition to local tectonic controls. Throughout the Miocene, the Red Sea and Gulf of Suez basins were connected to the Neo-Tethys Ocean and then to the proto-Mediterranean Sea from the north (Fig. 1a, b), as evidenced by the population of fossil coral biogeographically linked to Mediterranean fauna31,41. The absence of carbonate platform outcrops in the southern Red Sea during the Lower and Early Middle Miocene is attributed to the enduring continental environment42. From the Middle to Late Miocene, hypersaline conditions inhibited carbonate production4,43. The connection of the basin to the Indian Ocean from the south during the Pliocene restored viable salinity conditions (Fig. 1c), facilitating the return to carbonate production in the Red Sea44,45,46.

The nature and morphologies of carbonate platforms from the Pliocene are poorly understood because most post-Miocene platforms outcropping along the Red Sea are Quaternary43. Only a few Pliocene outcrops are exposed in the southern Red Sea, including the Farasan Archipelago and the coastal plain of Yemen (Fig. 1c). These exposures resulted from active salt tectonics (diapirs) exhuming these platforms to the surface47,48,49,50.

Geological setting

The Midyan Peninsula is at the junction between the northern Red Sea and Gulf of Aqaba, and it is underlain by two sedimentary basins: the onshore Midyan and offshore Duba half grabens (Fig. 2). These basins are about 60 and 90 km in length and 30 km wide. They initially formed as eastward-tilted half grabens from the Late Oligocene to the Early Miocene (~ 28−16 Ma) during the Gulf of Suez–Red Sea rifting phase42. Syn-rift strata in these basins can reach thicknesses of up to 6.5 km along the footwall margins of the bounding faults and reveal marked thinning and onlap southwestward onto the hanging-wall dip slope of the tilted blocks delineating their western margins (Fig. 2c).

Geological map and representative cross-section of the Midyan Peninsula region, adapted from Baby et al.42. Three generations of carbonate platforms are mapped and represented in shades of blue, with their subsurface equivalents marked with blue stars in the cross-section. The five focus areas discussed in the text, highlighted in green on the map, are presented in Figure S1.

In the southeastern extremity of the basin in the Wadi Aynunah area, the peneplained fault block of the Midyan Basin is exposed (Fig. 2a). In the northwest, along the Gulf of Aqaba, the Midyan Basin has undergone counterclockwise rotation, uplift, and partial erosion, exposing the basement and pre- and syn-rift strata, particularly in the Jabal Tayran area (Fig. 2a). This structural configuration resulted from complex strike-slip tectonics associated with the activation of the Dead Sea Transform from the Middle Miocene onwards16,51.

The post-rift interval exhibits a wedge-shaped geometry that thickens basinward to up to 3 km of accumulated sediment (Fig. 2c). In addition to thermal subsidence, post-rift accommodation was controlled by salt tectonics, with the initial Middle Miocene salt layer acting as the main décollement (see the stratigraphic description of the Mansiyah Formation) (Fig. 2c).

Syn-rift and post-rift stratigraphy

The deposition of the alluvial and lacustrine Al Wajh Formation52, which grades into marginal-to-shallow marine environments (Fig. 3), characterizes the onset of extension (~ 28–23 Ma)42. The early syn-rift sequence is well-exposed in the Jabal Tayran area (Fig. 2a), where fluvial red beds are overlain by a shallow marine carbonate ramp, which laterally transitions to evaporites12,13. These lithological units are defined as the Musayr and Yanbu formations, respectively38. The benthic foraminiferal assemblage and Sr isotope dating of the evaporites indicate an Aquitanian age (23–21 Ma)38. The climax of the rift sequence occurred during the Burdigalian (21–16 Ma)42 with the deposition of the deep marine Burqan Formation (Fig. 3), dominated by gravity-driven and turbidite-flow-driven siliciclastic sediments53.

Tectono-sedimentary chart of the northeastern Red Sea margin modified from Baby et al.4. Subformations: 1 = Musayr Formation, 2 = Yanbu Formation, 3 = Umm Luj Member of the Jabal Kibrit Formation, 4 = Wadi Waqb Member of the Jabal Kibrit Formation, 5 = Kial Formation.

The late syn-rift or transitional sequence, according to Baby et al.42, was deposited during the Langhian (16–14 Ma) above a regional unconformity along the western margins of the tilted-fault blocks (Figs. 2c and 3). Prograding deltaic geometries in the immediate hanging wall of the major basin-bounding faults evolved basinward to shelf deposits4 and primarily comprise silts with interbedded anhydrite layers, indicating restricted marine environments (Fig. 3). The proportion of evaporites increased over time until the ratio of siliciclastic/evaporite reverses, forming the Kial Formation52. Diagnostic planktonic foraminifera of this formation indicate N9 biozone (Langhian)38. Fringing platforms, known as the Wadi Waqb Member of the Jabal Kibrit Formation, developed contemporaneously on the crests of the fault blocks13and the eroded footwall of the basin-bounding faults exposed in the Wadi Aynunah area37 (Fig. 2a).

A thick layer (> 1 km) of salt (primarily halite) was deposited during the Serravallian (Fig. 3). This formation, the Mansiyah Formation, is only observed in the subsurface and displays a variety of salt withdrawal or expulsion structures51. The first post-rift unit, the Ghawwas Formation52, represents the maximum volume accumulation of sediment in the Red Sea Basin4and comprises a siliciclastic-dominated sequence with interbedded anhydrite layers, indicating restricted shallow marine to marginal environments38. Recent Sr isotope dating has constrained the deposition of this unit during the Upper Miocene, from ~ 13.2 to 6 Ma54. Above a regional Messinian unconformity55, the Plio-Pleistocene strata comprise open marine clastic sediment and aggrading carbonate platforms, defined as the Lisan Group38.

Results and discussion

Miocene and Pliocene carbonate platform characterization of the Midyan Peninsula

This section presents the details of the architecture, sedimentology, age, and diagenesis of carbonate platforms from five localities in the Midyan and Duba Basins (Fig. 2a and S1). These localities span four tectonostratigraphic units of the northeastern Red Sea margin, recording evolution from the marine rift basin during the Early-Middle Miocene to the passive continental margin during the Pliocene.

Jabal Tayran area

The Jabal Tayran area features an exhumed carbonate platform that is 50 to 75 m thick and spans an area of 10 × 5 km (Fig. 4a). The area exhibits apparent horizontal stratification indicative of low-relief morphology, such as a low-angle ramp or flat-topped platform (Fig. 4a’). The platform is tilted at an angle of 20° to the east-northeast and southeast. The platform unconformably overlies syn-rift alluvial sediments of the Al Wajh Formation, pre-rift sediments, and the basement. Lateral facies variation, from carbonates to evaporites of the Yanbu Formation, occurs northwest of the study area (Fig. 4a). To the northeast, open marine syn-rift sediments of the Burqan Formation conformably overlie the platform (Fig. 4a). This platform was lithostratigraphically designated as the Aquitanian Musayr Formation (Fig. 3). The observations and previous studies have highlighted the extensive lateral consistency of the platform lithofacies over several hundred meters13. Limestone beds are dominated by centimetric oyster shells (Fig. 5a). In thin sections, bivalve and rhodophyta fragments, echinoids, angular quartz grains (10–15%; Fig. 6a), and abundant benthic foraminifera (e.g., Amphistegina sp. and Miogypsina sp.) are embedded in a grainstone-to-packstone matrix. The previous description revealed that the oyster-rich limestone beds alternate with sandstone and thin coral-rich limestone (i.e., bafflestone)12. The carbonate biocomponents are relatively well preserved, with minimal dissolution or recrystallization (Fig. 6a).

Maxar satellite images (oblique views, left), uncrewed aerial vehicle, and field photographs (right) illustrating the morphology and tectono-sedimentary setting of the four Miocene carbonate systems in the Midyan Basin. The carbonate platforms and their associated slope deposits are highlighted in blue on the satellite images. Figure 2a and S1 provide location details. Noninterpreted satellite images and additional field photographs are provided in the supplementary material (Figs. S2–S5).

Thin-section micrographs illustrating the main carbonate facies observed in the carbonate platforms of the Midyan Peninsula region. Abbreviations: Am = Amphistegina sp., B = bivalve, Bz = bryozoan, C = coral, D = dasyclad algae, Mg = Miogypsina sp., Oy = oyster, Pf = planktonic foraminifera, Po = Planorbulina sp., Qz = quartz grain, and R = rhodophyda.

Midyan Basin north-bounding fault area

In this area, carbonate platforms are not preserved in situ. Their existence is inferred from what we interpret as their slope detritus draping the remnant footwall escarpment of the Midyan Basin border fault (Fig. 4b). These slope deposits comprise metric-thick carbonate beds dipping at 20° to 30° to the south-southeast and plurimetric coral-rich olistoliths, interbedded in the coarse-grained siliciclastic deposits of the open marine Burqan Formation (Fig. 4b’, b”). The limestone from olistoliths consists of bioclastic rudstone/grainstone with abundant coral fragments (Fig. 5c) embedded in a bioclastic packstone-to-grainstone matrix. Thin sections from the carbonate beds reveal a multitude of shallow marine components coexisting with coarse coral fragments (~ 30% of the assemblage), including abundant rhodophyta (branching and encrusting forms), benthic foraminifera (e.g., large forms of Amphistegina sp.), gastropods, bivalves, and bryozoans (Fig. 6b and c). These slope deposits also contain planktonic foraminifera, whereas quartz grains are rare and mostly angular. Overall, the samples reveal a low diagenetic overprint; carbonate components are relatively well preserved, with minimal dissolution or recrystallization. However, a few cemented fractures with blocky cements are noted.

Wadi Aynunah area

The Wadi Aynunah carbonate platform is well exposed and located on the footwall and hanging-wall dip slope of the Midyan fault block (Fig. 4c). The platform was lithostratigraphically assigned to the Langhian Wadi Waqb Member of the Jabal Kibrit Formation (Fig. 3). The underlying basement consists entirely of peneplained Precambrian igneous and metamorphic rocks. The footwall margin of the platform comprises a narrow (about 50 m width) progradational wedge flanking the scarp of the eroded fault (Fig. 4c’). The morphology of the footwall margin is nonlinear but broken up by promontories and embayments interpreted as paleo-valleys carved during sea-level lowstands. The top of the prograding wedge is unconformably overlain by a nearly horizontal bed (5–10 m thick) that extends over several hundreds of meters above the hanging-wall dip slope of the fault block, referred to as the inner platform in Fig. 4c.

The prograding sequence includes numerous coral colonies in growth position (Fig. 5d). The nearly horizontal carbonate bed exhibits fewer plurimetric sparse coral colonies. Coral builders are primarily poritid corals, including massive, columnar, and branched Porites, and faviid corals, dominated by Montastraea and Favites. The textures of the limestones in this area vary from grainstone to wackestone, primarily comprising rodophyta and dasyclad algae, foraminifera, gastropods, bivalves (including borings and molds), and a significant proportion of quartz (15–20%; Fig. 6e). Thin sections reveal coral fragments associated with rhodophyta (branching and encrusting forms), benthic foraminifera (Textularia sp., Haymanella sp., Quinqueloculina sp., Triloculina sp., Borelis melo melo, Amphistegina sp., Elphidium sp., Planorbulina sp., Gypsina sp., and Peneroplis sp.), and bryozoans (Fig. 6d). Most samples display strong diagenetic overprint with replacive dolomitization, vuggy dissolution, extensive recrystallization of microfossils (especially foraminifera) and calcite cementation (e.g., large blocky crystals).

Al Bad area

North of Al Bad, several hills are capped by carbonate platforms whose outcrop measure approximately 800 to 1000 m in length by 400 to 500 min width. These platforms are at the front of a large siliciclastic fan delta, originating from the intersection of the north and east-bounding faults of the Midyan half-graben and prograded south toward the city of Al Bad (Fig. 5d). This mixed carbonate-siliciclastic deltaic complex (Fig. S5) has never been described previously and could correspond to the Umm Luj Member of the Jabal Kibrit Formation (Fig. 3). It is conformably overlain by the alternating evaporites and marl deposits of the Kial Formation, suggesting a Burdigalian to Langhian age. Figure 5d’ depicts the detailed geometry of one of these platforms, consisting of an assemblage of metric-thick carbonates and siliciclastic beds over 65 m in height, dipping at about 20° to the east-southeast and partially eroded. The top displays massive coral colonies in growth positions (Fig. 5e), whereas its slope is characterized by large platform-derived olistoliths (Fig. 4d”). Thin sections from the top of the platform reveal coral fragments embedded in grainstone (rudstone) to packstone dominated by dasyclad algae fragments with frequent rhodophyta and foraminifera (Fig. 6f). The limestone exhibits significant diagenetic alterations, with poorly preserved microfossils. An intense dissolution of bio components occurs, and moldic pore types are very common. Both dolomitization of the matrix and components and dedolomitization are prevalent.

Offshore Duba Basin area

The seabed morphology of the Duba Basin is rugged and consists of shallow (about 15 m in depth) attached and detached carbonate platforms (Fig. 7a). The detached platforms range in length from less than 1 to 13 km and can reach heights of up to 400 m. Their shapes highly vary, ranging from round to elongated, including complex subangular morphologies. Most of the platforms have steep slopes with angles of 75° to 80°. The southwestern slope of the Yuba and Burqan platforms feature staircase-shaped morphologies associated with several terrace levels. Except for the Yuba platform, the seismic profiles reveal aggrading geometries up to 1000 m high (Fig. 7b, c). These platforms form above fault displacement anticlines, related to extensional rollovers with salt rollers and diapirs. Figure 7b presents evidence of backstepping seismic geometries along the western edge of Yuba Island, aligning with observations from the bathymetric data, indicating that the southwestern edge of the Burqan and Yanbu platforms has retrograded in discrete steps. These backstepping morphologies correspond with the location of the footwall of the Duba fault block (Fig. 2), marked by a change in the pre-salt topography from a nearly horizontal to a basin-dipping configuration.

Oblique view of the sea-floor topography and interpreted seismic profiles of the offshore Duba area, presenting isolated carbonate platforms (highlighted in blue). Figure 2a and S1 provide location details. Ages determined from Sr isotope stratigraphy on rock samples from Well 1 and the dive by the remotely operated vehicle at the edge of Yuba Island (Table 1) are projected onto the profiles.

In the offshore Duba Basin area, the carbonate platforms belonging to the Lisan Group (Fig. 3) are growing above post-rift siliciclastic sediments of the Late Miocene Ghawwas Formation. The 87Sr/86Sr isotope analysis on well cuttings from Well 1 indicates an age of 5.3 ± 0.1 Ma at the base of the Yuba carbonate platform (Table 1and Fig. S6). The age of the coral samples collected along the eastern edge of the Sila platform and the aragonite cement samples on Yuba Island confirm that the platforms have been aggrading during the Pliocene (Table 1). The limestone samples from the well cuttings comprise coarse packstone-grainstone dominated by branched and encrusted rhodophyta associated with coral fragments, echinoid spines, bivalve fragments, and ooids (Fig. 6g, h). Benthic foraminifera encompass Borelis schlumbergeri, Quinqueloculina sp., Triloculina sp., and Amphistegina sp. Overall, we observed a moderate diagenetic overprint and some dissolution with moldic pores and blocky cement in the bottom part of Well 1 (Fig. S6).

Spatiotemporal evolution of carbonate platforms via the tectono-sedimentary evolution of the northeast Red Sea rifted margin

Aquitanian (23–21 Ma): early syn-rift stage

During the Aquitanian, the northern Red Sea was approximately 50 km wide and was a branch of the Neo-Tethys Ocean (Fig. 1a), creating an estuarine-like paleoenvironment. The flat-topped morphology of the Jabal Tayran carbonate platform suggests a low-relief basin, consistent with the low tectonic subsidence of the basin (Fig. 8). The presence of quartz grains in the limestones and the dominance of mollusks as primary carbonate producers indicate shallow-water marine conditions characterized by high nutrient levels (mesotrophic) with regular fluvial activity. Although corals were present, they were not dominant and only formed sparse bioherms12. Beds rich in ooid and microbialite deposits, alternating with the oyster beds13, suggest short periods of restriction, high salinity, and limited connection to the global ocean. The lack of a strong diagenetic overprint on carbonate components, along with the emersion surface, suggests that the platform was rapidly buried.

Evolution of the morphology and ecology of carbonate platforms in the Midyan Peninsula region, contextualized in their tectono-sedimentary framework. a Schematic block diagrams of the Midyan and Duba Basins depicting their configuration and sedimentary accommodation space throughout the tectonic history of the northeastern Red Sea. The time-depth curve illustrates the evolution of tectonic subsidence in the basin over time. b Schematic cross-sections of the platforms depicting their overall geometry and relationship with the underlying basement. c Principal carbonate producers across the depositional profiles of the platforms.

Burdigalian (21–16 Ma): rift climax stage

No in situ carbonate platforms were identified during this period. However, the slope carbonate deposits of the north-bounding fault area of the Midyan Basin demonstrate that fringing platforms existed on the basin margins. The local increase in tectonic subsidence during the rift climax may have contributed to the creation of significant accommodation space in the basin (Fig. 8), isolating areas from siliciclastic inputs and promoting the development of open marine carbonate platforms rather than estuarine-related carbonate platforms. The massive coral and rhodophyta in the olistoliths and finer slope deposits, observed as numerous fragments, suggest a shift from a mollusk-dominated (Aquitanian) to coral and rhodophyta-dominated (Burdigalian) carbonate factory.

Langhian (16–14 Ma): transition (late syn-rift) stage

Two types of carbonate platforms accompany this transitional tectonic period (Fig. 8). First, fringing platforms developed on the footwall margin of the eroded Midyan fault block in the Wadi Aynunah area. The good preservation of carbonate components indicates that these platforms were exposed to near-surface conditions shortly after deposition. We interpret this platform to be a fault-block carbonate platform7and, more specifically, a post-tectonic footwall carbonate platform10. The compilation of previous studies, supplemented by the mapping based on remote-sensing data, reveals a consistent pattern of fringing platforms extending along the conjugate margins of the northern Red Sea over a distance of 800 km (Fig. 2b).

Second, platforms that developed on the top and slope of deltaic clinoforms in the Al Bad area are interpreted as top-delta platforms7. The prograding seismic geometries of the transition unit defined by Baby et al. (2024)4in the subsurface to the northwest of the Midyan Basin are the subsurface lateral equivalent of this deltaic complex. The complex is an outcropping in the vicinity of the city of Al Bad, as it was exhumed during the uplift of the western part of the basin16,42.

These two types of platforms reflect a deceleration of tectonic subsidence of the basin (Fig. 8), enabling the development of two types of substrates, the initial topography for carbonate to grow. The platform grew directly on the peneplained basement, far from siliciclastic inputs. In contrast, where siliciclastic inputs from the erosion and retreat of rift shoulders56 dominated, a mixed deltaic complex developed.

Serravallian and younger (14 Ma–present): Post-rift period

The onset of the post-rift period coincided with the isolation of the Red Sea from the proto-Mediterranean Sea and the establishment of hypersaline conditions in the basin, resulting from partial or complete disconnection to the open ocean. These conditions, prevalent during the Late Miocene, inhibited carbonate production. The return of the carbonate sedimentation in the northern Red Sea is dated to the end of the Miocene (~ 5.5 Ma). This resurgence is marked by the establishment of broad platforms, either attached or unattached, which aggraded over several hundred meters with a carbonate accumulation rate of 100 to 250 m/Myr. We interpret these platforms to be passive margin platforms7, consistent with the tectonic setting of the Red Sea that has prevailed since the Middle Miocene (Fig. 8). Seismic data indicates that the location and morphology of these platforms are also strongly influenced by salt tectonics and the rift-inherited topography. When the pre-salt topography is gentle, fault-displacement anticlines associated with salt rollers and diapirs provide substrate for platform growth (e.g., Wallah and Sila islands in Fig. 7). On the other hand, as the slope steepens—such as along the southwestern edge of the Duba Basin—platforms experience downslope sliding toward the basin, resulting in backstepping geometries at the edges of the platform and eventual drowning (e.g., Yuba and Burqan islands in Fig. 7).

Comparison with the evolution of carbonate platforms in the Mediterranean region

During the Aquitanian and Burdigalian, Mediterranean carbonate platforms were predominantly characterized by ramp systems, with seagrass meadows in the upper ramp and large benthic foraminifera (LBF) dominating the lower ramp57,58. Although not the primary carbonate producers, mesophotic coral mats and mounds were widespread and exhibited high diversity during this period58. A similar depositional pattern is observed in the Aquitanian carbonate platforms of the Midyan Peninsula, particularly in the Jabal Tayran area (Fig. 2), where corals are scarce, and mollusks represent the dominant carbonate-producing biota.

During the late Burdigalian, the transition from a warm arid to a warm humid climate associated with the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum (MMCO)5led to rising global sea surface temperatures, increased oceanic primary productivity, and enhanced inland precipitation. These environmental changes contributed to greater continental runoff, higher turbidity, and elevated nutrient levels in the Mediterranean region3,57,59,60, leading to a decline in LBF assemblages, while oligophotic organisms such as dasyclad algae, rhodophytes, and mollusks proliferated57,58,61.

In contrast, the Langhian carbonate platforms of the northern Red Sea, including those examined in this study (Al Bad and Wadi Aynunah areas, Fig. 2) and their stratigraphic equivalents along the conjugate Egyptian margin (Fig. 1), show an evolutionary trajectory distinct from the primary carbonate producers of the proto-Mediterranean Sea. While algae became dominant in both regions, corals also thrived along both margins of the northern Red Sea, forming massive coral framestones and densely packed in-situ colonies on platform edges14,29,31,33. This disparity is likely attributable to the paleogeography of the Red Sea during that period, which maintained only a partial connection to the proto-Mediterranean Sea. The presence of small adjacent catchments along the shoulders of the Red Sea rift56and the limited siliciclastic input4 likely created environmental conditions conducive to coral proliferation.

The Serravallian marked the end of the MMCO and the onset of global cooling and aridification across the Mediterranean region58. This climatic shift led to the widespread establishment of euphotic conditions in shallow waters throughout the proto-Mediterranean Sea62, triggering a fundamental reorganization of carbonate systems. Corals transitioned from secondary to primary carbonate producers, forming modern reef complexes in the shallowest parts of the water column58,62. In contrast, carbonate production in the Red Sea largely ceased due to the increasingly restricted conditions caused by the closure of the seaway to the proto-Mediterranean Sea4. This restriction led to elevated salinity levels, inhibiting carbonate production and resulting in a pronounced hiatus that persisted until the end of the Miocene (this study). In addition, the retreat and erosion of the Red Sea rift shoulders, following the cessation of tectonic activity along the border faults56, significantly increased siliciclastic input into the basin4. This process, combined with the restricted environments of the basin, has likely contributed in inhibiting carbonate production by increasing water turbidity and causing nutrient saturation in the basin.

Our study suggests that the emergence of modern reefs in the Red Sea occurred later than in the Mediterranean, at the end of the Miocene. This delay coincided with the re-flooding of the Red Sea from the Indian Ocean through Bab el Mandeb (Fig. 1), which restored salinity levels suitable for carbonate-producing organisms43. Additionally, the intensification of hyper-arid conditions since the late Miocene4 likely played a key role in the development of Pliocene-to-modern carbonate systems in the region by further reducing continental weathering and maintaining the clear-water conditions essential for sustained carbonate production.

Conclusions

By integrating onshore and offshore surface and subsurface data with new Sr isotope dating, we have reconstructed the morphological transformations and development of the carbonate platforms of the northeastern Red Sea rifted margin, from its rifting stage to its passive margin stage. Their evolution reveals the interplay of tectonic activity, paleo-environmental variations, and carbonate-producing organisms driving the spatial and temporal variations in platform morphology, distribution, and ecology during the past 23 million years.

During the early to middle Miocene rifting period of the Red Sea the platforms evolved from mollusk-dominated ramps to coral- and algal-dominated fault blocks and top-delta platforms. Following a hiatus of more than 8 million years caused by extreme salinity conditions in the basin, offshore bank platforms, typical of passive margin setting, developed during the Pliocene. This resurgence of carbonate sedimentation at the end of the Miocene highlights the perennial continuity of a mesophotic coral-agal carbonate factory. This continuity, spanning over 20 million years, connects modern mesophotic foraminiferal-algal nodules and coral bioherms of the northern Red Sea63,64,65 with their ancient Miocene counterparts in the Midyan Peninsula.

Materials and methods

Onshore mapping relies on remote-sensing data (Maxar imagery at a resolution of 0.6 m) and topographic data extracted from the Shutter Radar Topography Mission with a resolution of 30 m. Two field investigations supplemented this remote analysis and were conducted in April 2021 and March 2022 in the Midyan region, where we employed imagery from an uncrewed aerial vehicle and collected in situ observations. Samples were collected for biostratigraphy, paleo-environmental reconstructions, and diagenesis interpretations. Offshore mapping was based on a proprietary bathymetric survey, gridded into a 15-m resolution digital elevation model, and GEBCO bathymetric data gridded into a 15 arc-second interval (about 500 m) digital elevation model. Height rock samples were collected along the eastern flank of Sila Island using a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) during the NEOM OceanX Red Sea Deep Blue Expedition in 2020. Onshore and offshore mapping was processed using ArcGIS Pro 3.0.0 software.

Subsurface data comprise two offshore seismic reflection dip lines along the Yuba and Wallah Islands, the Sila Island, and an unnamed island (Fig. 7). The lines are extracted from a proprietary three-dimensional survey, processed via prestack depth migration, and depth-converted using a multilayered velocity model. Calibration was performed using data from the offshore exploration well (Well 1; Fig. S5). Well cuttings were used for biostratigraphy and Sr isotope stratigraphy, paleo-environmental reconstructions, and diagenesis interpretations.

Sedimentological interpretation combines field and thin-section observations. The reconstruction of carbonate depositional environments was based on the interpretation of biological assemblages and depositional textures, with biostratigraphic ranges sourced from the planktonic foraminiferal zonal scheme proposed by Wade et al.66.

Fourteen limestone samples were dated using Sr isotope stratigraphy (Table 1). Cutting samples from Well 1 were separated and powdered, and their 87Sr/86Sr ratios were measured using thermal ionization mass spectrometry at the University of Granada and University of Madrid. For ROV- and field-picked samples from Yuba Island, the 87Sr/86Sr ratio was measured on 80-µm-thick polished sections using laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry at UC Santa Barbara. The NBS 987 standard yielded accurate values with an error of 0.710249 ± 0.000002 (n= 20), and no correction for the standard was necessary. These results were converted to ages using LOWESS v6, aligned to the GTS2020 time scale67.

Data availability

The data for this study are available in the paper and supplementary materials.

References

Perrin, C. in Phanerozoic Reef Patterns Vol. 72 (eds W. Kiessling, E. Flügel, & J. Golonka) 587–621SEPM Special Publication, (2002).

Bellahsen, N., Faccenna, C., Funiciello, F., Daniel, J. M. & Jolivet, L. Why did Arabia separate from Africa? Insights from 3-D laboratory experiments. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 216, 365–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0012-821x(03)00516-8 (2003).

Torfstein, A. & Steinberg, J. The Oligo–Miocene closure of the Tethys ocean and evolution of the proto-Mediterranean sea. Sci. Rep. 10, 13817. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70652-4 (2020).

Baby, G. et al. Sediment routing systems of the Eastern red sea rifted margin. Earth Sci. Rev. 249, 104679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2024.104679 (2024).

Zachos, J., Pagani, M., Sloan, L., Thomas, E. & Billups, K. Trends, rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65 ma to present. Science 292, 686–693. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1059412 (2001).

Delaunay, A. et al. Structure and morphology of the red Sea, from the mid-ocean ridge to the ocean-continent boundary. Tectonophysics 849, 229728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2023.229728 (2023).

Bosence, D. A genetic classification of carbonate platforms based on their basinal and tectonic settings in the cenozoic. Sed. Geol. 175, 49–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2004.12.030 (2005).

Dullo, W. C. & Montaggioni, L. in In Sedimentation and Tectonics in Rift Basins: Red Sea - Gulf of Aden. 583–594 (eds Purser, B. H. & Bosence, D. W. J.) (Springer Netherlands, 1998).

Purkis, S. J., Harris, P. M. & Ellis, J. Patterns of sedimentation in the contemporary red sea as an analog for ancient carbonates in rift settings. J. Sediment. Res. 82, 859–870. https://doi.org/10.2110/jsr.2012.77 (2012).

Cross, N. E. & Bosence, D. W. J. in Controls on Carbonate Platform and Reef Development Vol. 89 (eds J. Lukasik & J. A. Simo) 0SEPM Society for Sedimentary Geology, (2008).

Burchette, T. P. Tectonic control on carbonate platform facies distribution and sequence development: miocene, Gulf of Suez. Sed. Geol. 59, 179–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/0037-0738(88)90076-0 (1988).

Dullo, W. C., Hötzl, H. & Jado, A. R. New stratigraphical results from the tertiary sequence of the Midyan area, NW Saudi Arabia. Newsl. Stratigr. 12, 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1127/nos/12/1983/75 (1983).

Koeshidayatullah, A., Al-Ramadan, K., Collier, R. & Hughes, G. W. Variations in architecture and Cyclicity in fault-bounded carbonate platforms: early miocene red sea rift, NW Saudi Arabia. Mar. Pet. Geol. 70, 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2015.10.017 (2016).

Purser, B. H., Plaziat, J. C. & Rosen, B. R. in Models for Carbonate Stratigraphy from Miocene Reef Complexes of Mediterranean Regions, SEPM Concepts in Sedimentology and Paleontology Vol. 5 (eds E. K. Franseen, M. Esteban, W. C. Ward, & J.-M. Rouchy) 347–366 (SEPM (Society for Sedimentary Geology), (1996).

Rowlands, G., Purkis, S. & Bruckner, A. Diversity in the geomorphology of shallow-water carbonate depositional systems in the Saudi Arabian red sea. Geomorphology 222, 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2014.03.014 (2014).

Bayer, H. J., Hotzl, H., Jado, A. R., Roscher, B. & Voggenreiter, W. Sedimentary and structural evolution of the Northwest Arabian red sea margin. Tectonophysics 153, 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-1951(88)90011-X (1988).

Ribot, M. et al. Vertical Deformation Along a Strike-Slip Plate Boundary: The Uplifted Marine Terraces of the Gulf of Aqaba and Tiran Island, at the Southern End of the Dead Sea Fault. Tectonics 43, e (2023). TC007977 https://doi.org/10.1029/2023TC007977 (2024).

Bosence, D., Cross, N. & Hardy, S. Architecture and depositional sequences of tertiary fault-block carbonate platforms; an analysis from outcrop (Miocene, Gulf of Suez) and computer modelling. Mar. Pet. Geol. 15, 203–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-8172(98)00016-6 (1998).

Petrovic, A. et al. Fragmentation, rafting, and drowning of a carbonate platform margin in a rift-basin setting. Geology 51, 242–246. https://doi.org/10.1130/g50546.1 (2023).

Smith, J. E. & Santamarina, J. C. Red sea evaporites: formation, creep and dissolution. Earth Sci. Rev. 232, 104115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2022.104115 (2022).

Bosworth, W., Crevello, P., Winn, R. D. & Steinmetz, J. in Sedimentation and Tectonics in Rift Basins: Red Sea-Gulf of Aden (eds B. H. Purser & D. W. J. Bosence) 77–96, Springer Netherlands, (1998).

Montenat, C., Orszag-Sperber, F., Plaziat, J. C. & Purser, B. H. in In Sedimentation and Tectonics in Rift Basins: Red Sea - Gulf of Aden. 146–161 (eds Purser, B. H. & Bosence, D. W.) (Chapman & Hall, 1998).

Evans, A. L. Neogene tectonic and stratigraphic events in the Gulf of Suez rift area. Egypt. Tectonophysics. 153, 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-1951(88)90018-2 (1988).

Winn, R. D. Jr., Crevello, P. D. & Bosworth, W. Lower miocene Nukhul formation, Gebel El zeit, Egypt: model for structural control on early synrift strata and reservoirs, Gulf of Suez. AAPG Bull. 85, 1871–1890. https://doi.org/10.1306/8626d095-173b-11d7-8645000102c1865d (2001).

Purser, B. H. & Hötzl, H. The sedimentary evolution of the red sea rift: a comparison of the Northwest (Egyptian) and Northeast (Saudi Arabian) margins. Tectonophysics 153, 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-1951(88)90015-7 (1988).

Moustafa, A. R. & Khalil, S. M. in The Geology of Egypt (eds Z. Hamimi 295–342 (Springer International Publishing, (2020).

Cross, N. E., Purser, B. H. & Bosence, D. W. J. in Sedimentation and Tectonics in Rift Basins: Red Sea - Gulf of Aden (eds B. H. Purser & D. W. J. Bosence) 271–295. Springer Netherlands, (1998).

El Haddad, A., Aissaoui, D. M. & Soliman, M. A. Mixed carbonate-siliciclastic sedimentation on a miocene fault-block, Gulf of Suez, Egypt. Sed. Geol. 37, 185–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/0037-0738(84)90007-1 (1984).

James, N. P., Coniglio, M., Aissaoui, D. M. & Purser, B. H. Facies and geologic history of an exposed miocene Rift-Margin carbonate platform: Gulf of Suez, Egypt. AAPG Bull. 72, 555–572 (1988).

Montenat, C. et al. Tectonic and sedimentary evolution of the Gulf of Suez and the Northwestern red sea. Tectonophysics 153, 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-1951(88)90013-3 (1988).

Perrin, C., Plaziat, J. C. & Rosen, B. R. in Sedimentation and Tectonics in Rift Basins: Red Sea - Gulf of Aden (eds Bruce H. Purser & Dan W. J. Bosence) 296–319Springer Netherlands, (1998).

Purser, B. H. & Plaziat, J. C. in Sedimentation and Tectonics in Rift Basins: Red Sea - Gulf of Aden (eds B. H. Purser & D. W. J. Bosence) 320–346Springer Netherlands, (1998).

Corniglio, M., James, N. P. & Assaoui, D. M. in Models for Carbonate Stratigraphy from Miocene Reef Complexes of Mediterranean Regions Vol. 5 (eds E. K. Franseen, M. Esteban, W. C. Ward, & J.-M. Rouchy) 367–384 (SEPM, 1996).

Schroeder, J. H., Toleikis, R., Wunderlich, H. & Kuhnert, H. in Sedimentation and Tectonics in Rift Basins: Red Sea - Gulf of Aden (eds B. H. Purser & D. W. J. Bosence) 190–210 (Springer Netherlands, 1998).

Davies, F. B. In Geoscience Map GM-83C (Deputy Ministry for Mineral Resources, Jeddah, 1985).

Davies, F. B. & Grainger, D. J. In Geoscience Map GM-82A (Deputy Ministry for Mineral Resources, Jeddah, 1985).

Hughes, G. W. Micropalaeontology and palaeoenvironments of the miocene Wadi Waqb carbonate of the Northern Saudi Arabian red sea. Geoarabia 19, 59–108. https://doi.org/10.2113/geoarabia190459 (2014).

Hughes, G. W. & Johnson, R. S. Lithostratigraphy of the red sea region. Geoarabia 10, 49–126. https://doi.org/10.2113/geoarabia100349 (2005).

Mandurah, M. H. & Aref, M. A. Lithostratigraphy and standard microfacies types of the neogene carbonates of Rabigh and Ubhur areas, red sea coastal plain of Saudi Arabia. Arab. J. Geosci. 5, 1317–1332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-011-0281-z (2012).

Pellaton, C. In Geoscience Map GM-61C (Deputy Ministry for Mineral Resources, Jeddah, 1982).

Pisapia, C., Vicens, G. M., Benzoni, F. & Westphal, H. Mediterranean imprint on coral diversity in the incipient red sea (Burdigalian, Saudi Arabia). PALAIOS 39, 233–242. https://doi.org/10.2110/palo.2023.025 (2024).

Baby, G., Delaunay, A., Aslanian, D. & Afifi, A. M. The tectonostratigraphic latitudinal record of the Eastern red sea margin. Bull. De La. Société Géologique De France. 195 https://doi.org/10.1051/bsgf/2024009 (2024).

Taviani, M. in In Sedimentation and Tectonics in Rift Basins: Red Sea - Gulf of Aden. 574–582 (eds Purser, B. H. & Bosence, D. W. J.) (Springer Netherlands, 1998).

Braithwaite, C. J. R. in In Red Sea. 22–44 (eds Edwards, A. J. & Head, S. M.) (Pergamon, 1987).

Fleisher, R. L. Preliminary report on late neogene red sea foraminifera, deep sea drilling project. Leg. 23B, 985–1011 (1974).

Por, F. D. The Legacy of the TethysVol. 63 (Kluwer Academic, 1989).

Almalki, K. A., Ailleres, L., Betts, P. G. & Bantan, R. A. Evidence for and relationship between recent distributed extension and halokinesis in the Farasan Islands, Southern red Sea, Saudi Arabia. Arab. J. Geosci. 8, 8753–8766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-015-1792-9 (2015).

Bantan, R. A. Geology and Sedimentary Environment of Farasan Bank (Saudi Arabia) Southern Red Sea: a Combined Remote Sensing and Field Study PhD thesis, University of London Royal Holloway, (1999).

Bosence, D. W. J. et al. in In Sedimentation and Tectonics in Rift Basins Red Sea:- Gulf of Aden. 448–454 (eds Purser, B. H., Dan, W. J. & Bosence) (Springer Netherlands, 1998).

Khalil, H. M. Pliocene–Pleistocene stratigraphy and macrofauna of the Farasan Islands, South East red Sea, Saudi Arabia. Arab. J. Geosci. 5, 1223–1245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-011-0300-0 (2012).

Tubbs, R. E. J. et al. Midyan Peninsula, Northern red Sea, Saudi Arabia: seismic imaging and regional interpretation. Geoarabia 19, 165–184. https://doi.org/10.2113/geoarabia1903165 (2014).

Hughes, G. W. & Filatoff, J. Middle East petroleum geosciences, Geo’94. I Al-Husseini). 2 (ed M, 517–528 (1995). (Gulf petroLink.

Hughes, G. W., Grainger, D. J., Abu-Bshait, A. J. & Abdul-Rahman, M. J. Lithostratigraphy and Depositional History of Part of the Midyan Region, Northwestern Saudi Arabia. GeoArabia 4, 503–542, (1999). https://doi.org/10.2113/geoarabia0404503

Pensa, T., Huertas, A. D., Aljahdali, A. H. & Afifi, A. M. in The International Meeting for Applied Geoscience & Energy (IMAGE).

Afifi, A. M., Tapponnier, P. & Raterman, N. S. in 11th Middle east geosciences conference and exhibition. 10–12 (AAPG Search and Discovery Article).

Delaunay, A., Baby, G., Paredes, E. G., Fedorik, J. & Afifi, A. M. Evolution of the Eastern red sea rifted margin: morphology, uplift processes and source-to-sink dynamics. Earth Sci. Rev. 250, 104698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2024.104698 (2024).

Cornacchia, I., Brandano, M. & Agostini, S. Miocene paleoceanographic evolution of the mediterranean area and carbonate production changes: A review. Earth Sci. Rev. 221, 103785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2021.103785 (2021).

Esteban, M. in Models for Carbonate Stratigraphy from Miocene Reef Complexes of the Mediterranean Regions. Vol. 5 (eds E. K. Franseen, M. Esteban, W. C. Ward, & J.-M. Rouchy) 3–53SEPM, (1996).

FÖLLMI, K. B., GERTSCH, B., DE KAENEL, R. E. N. E. V. E. Y. J. P., STILLE, P. & E. & Stratigraphy and sedimentology of phosphate-rich sediments in Malta and south-eastern Sicily (latest oligocene to early late Miocene). Sedimentology 55, 1029–1051. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3091.2007.00935.x (2008).

John, C. M., Mutti, M. & Adatte, T. Mixed carbonate-siliciclastic record on the North African margin (Malta)—coupling of weathering processes and mid miocene climate. GSA Bull. 115, 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1130/0016-7606(2003)115<0217:MCSROT>2.0.Co;2 (2003).

Franseen, E. K., Esteban, M., Ward, W. C. & Rouchy, J. M. Models for Carbonate Stratigraphy from Miocene Reef Complexes of the Mediterranean Regions. Vol. 5 402SEPM, (1996).

Pomar, L., Baceta, J. I., Hallock, P., Mateu-Vicens, G. & Basso, D. Reef Building and carbonate production modes in the west-central Tethys during the cenozoic. Mar. Pet. Geol. 83, 261–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2017.03.015 (2017).

Bracchi, V. A. et al. Mesophotic foraminiferal-algal nodules play a role in the red sea carbonate budget. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 288. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00944-w (2023).

Fricke, H. W. & Hottinger, L. Coral bioherms below the euphotic zone in the red sea. Mar. Ecol. - Progress Ser. 11, 113–117 (1983).

Hottinger, L. in In Coated Grains. 23–37 (eds Peryt, T. M.) (Springer-, 1983).

Wade, B. S., Pearson, P. N., Berggren, W. A., Pälike, H. Review and revision of Cenozoic tropical planktonic foraminiferal biostratigraphy and calibration to the geomagnetic polarity and astronomical time scale. Earth Sci. Rev. 104(1–3), 111–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2010.09.003 (2011).

McArthur, J. M., Howarth, R. J., Shields, G. A. & Zhou, Y. in Geologic Time Scale 2020 (eds F. M. Gradstein, J. G. Ogg, M. D. Schmitz, & G. M. Ogg) 211–238 (Elsevier, 2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by KAUST research grant 4082 to Professor A. M. Afifi. We thank NEOM for granting a permit to conduct the fieldwork and for facilitating and coordinating the OceanX Red Sea Deep Blue Expedition. We are grateful to OceanX and the crew of OceanXplorer for their operational and logistic support throughout the expedition, especially the ROV and submersible teams for data acquisition and sample collection. Special thanks are given to J. Fedorik, J. Ye, M. Petrova, and J. Zerpa for their field support and to J. Carpenter for the preparation of the thin sections. Finally, we thank three anonymous reviewers for their comments which helped us to improve the clarity and quality of our manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.P.: Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing-original draft, Formal analysis. G.B.: Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing-original draft, Visualization. T.T.: Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing-original draft. A.D.: Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing-review & editing. A.D-H.: Formal analysis, Validation. A.M.A.: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing-review & editing, Validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pensa, T., Baby, G., Teillet, T. et al. Evolution of carbonate platforms in the northeast Red Sea during the last 23 million years. Sci Rep 15, 10332 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92219-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92219-x

This article is cited by

-

Desiccation of the Red Sea basin at the start of the Messinian salinity crisis was followed by major erosion and reflooding from the Indian Ocean

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)