Abstract

The hemoglobin-to-red blood cell distribution width ratio (HRR) has emerged as a potential predictor of various health outcomes. This study aimed to investigate the association between HRR and all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality. This cohort study used data from 28,825 participants in the 1999–2018 U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Weighted Cox regression was used to assess the associations between HRR and mortality. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) models evaluated the non-linear associations between HRR and mortality risk. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of the study results. Trend tests assessed the temporal trends of mean HRR. Lower HRR was significantly linked to increased risks of all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality. According to the fully adjusted model, the highest quintile of HRR (Q5) showed lower mortality risks compared to the lowest quintile (Q1): all-cause mortality (HR 0.47, 95% CI 0.40, 0.55), cancer mortality (HR 0.51, 95% CI 0.37, 0.71), and cardiovascular mortality (HR 0.43, 95% CI 0.32, 0.56). A significant trend effect was observed across HRR quintiles (P for trend < 0.0001). Nonlinear association analyses suggested a linear relationship between HRR and cardiovascular mortality, while “L”-shaped associations were observed for all-cause and cancer mortality. Notably, the mean HRR levels decreased from 1.18 (95% CI 1.16–1.19) in 1999–2000 to 1.07 (95% CI 1.05–1.08) in 2017–2018. An inverse association between HRR and mortality risk was found, with lower HRR levels indicating higher mortality risk. Over the past two decades (1999–2018), there has been a significant decline in HRR levels among U.S. adults. HRR may serve as a valuable and easily obtainable predictor for mortality risk assessment in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mortality prediction and risk assessment are crucial aspects of public health and clinical practice1,2. Recently, there has been a growing interest in identifying novel, easily obtainable biomarkers that can provide valuable insights into an individual’s overall health status and mortality risk3,4. Among these, hematological parameters have garnered significant attention due to their widespread availability and potential to reflect various physiological and pathological processes5,6. Hemoglobin (Hb) and red cell distribution width (RDW) are two key blood parameters that are closely associated with various health outcomes.

Hemoglobin is an important indicator of the oxygen-carrying capacity of red blood cells, and low Hb levels are not only indicative of malnutrition and decreased immune response but may also affect a patient’s ability to tolerate treatment7. Studies have shown that low Hb levels are associated with adverse outcomes in cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, such as acute coronary syndrome8, heart failure9, and ischemic stroke10,11. In studies of non-traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage, it was found that for every 1 g/dL increase in Hb, the risk of hematoma volume and hematoma expansion decreased by 14% and 7%12, respectively. Previous oncology research has demonstrated that pre-treatment anemia in various cancers13, including non-small cell lung cancer14, head and neck cancer15, cervical cancer16, and colorectal cancer17, predicts a poor prognosis. In contrast, RDW, a quantitative measure of circulating red cell size variability, usually tends to be elevated in the presence of either ineffective erythropoiesis or increased red blood cell destruction. RDW has also demonstrated significant value in the prediction of poor prognosis for a wide range of diseases, especially in cardiovascular diseases such as heart failure18,19,20, cardiovascular disorders21,22, and ischemic stroke23. With continuous and in-depth research on RDW in clinical applications, its importance as a prognostic marker of disease has become widely recognized.

Recently, the HRR has been recognized as a novel composite marker with the unique advantage of reflecting both the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood and the underlying erythropoietic stress or dysfunction, demonstrating superior prognostic value over single-component prognostic assessments, thus providing stronger support for comprehensive assessment of an individual’s health status. While preliminary studies have suggested a potential association between HRR and health outcomes, such as depression24, all-cause mortality in septic patients with atrial fibrillation25, tumor prognosis26, etc., comprehensive investigations into its relationship with mortality across different causes of death are lacking. To fill this knowledge gap, this study utilized a nationally representative sample of the U.S. population from 1999 to 2018, focusing on the relationship between HRR and all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality among adults aged 20 and older. Additionally, we investigated the changes in mean HRR over time to gain a deeper understanding of its potential as a predictive indicator in clinical practice and public health strategies.

Materials and methods

Data source and study population

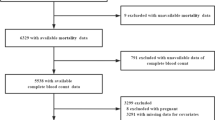

This study utilized data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a large-scale national survey designed and continuously implemented by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) to comprehensively assess the health and nutritional status of the U.S. noninstitutionalized population, using a multistage probability sampling methodology—a sampling strategy that ensures a representative sample. We used NHANES data from 1999 to 2018 including 28,825 participants aged 20 years or older, and the participant screening process is shown in Fig. 1. We excluded the following participants: (1) participants with incomplete HRR data; (2) participants with missing or ineligible survival status follow-up data determined by the ELIGSTAT variable in the NHANES public-use mortality data (specifically excluding participants classified as “under 18, not publicly releasable” or “ineligible”); (3) participants with incomplete data on other covariates.

HRR assessment

The NHANES database utilizes the Beckman Coulter method for blood cell counts and measurements27,28. The method incorporates an automated dilution mixing device to process samples and a single-beam photometer to measure hemoglobin. Hb and RDW data were extracted from the data and used to calculate HRR. Detailed procedures are available in the NHANES Laboratory/Medical Technician Manual (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/public/2017/labmethods/CBC-J-MET-508.pdf). The specific formula for calculating HRR is shown below:

Mortality assessment

Follow-up data released by NHANES were used to determine the survival status of participants, with a data cutoff date of December 31, 2019. These data were obtained by probability matching with death certificate records from the National Death Index (NDI). The probabilistic matching method, employed by NCHS, assigns weights to potential matches based on several identifying variables including Social Security Number, name, date of birth, sex, and state of residence to determine the likelihood that two records belong to the same individual. A match is considered true when the total weight exceeds a predetermined threshold. For confirmed matches, the underlying cause of death was determined according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10). This study examined all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular disease mortality. Based on the ICD-10 coding system used in the follow-up data, specific causes of death were classified as follows: Cancer mortality included deaths coded as malignant tumors (C00-C97), while Cardiovascular mortality encompassed deaths coded as cardiovascular diseases (I00-I09, I11, I13, I20-I51) and cerebrovascular diseases (I60-I69).

Definitions of covariates

Multiple covariates were included in the analyses of this study, covering four main areas: demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors, socioeconomic status, and health status indicators. Demographic characteristics included age, sex, and ethnicity (categorized as non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, and Other/multiracial). The lifestyle factors were collected through self-reported questionnaires, including smoking status (Never, Former, Now), alcohol use (Drinker, Non-drinker), and physical activity. Socioeconomic status was evaluated using two indicators: (1) income level, categorized using the Ratio of Family Income to Poverty (PIR) as Poor (PIR < 1) or Not-poor (PIR ≥ 1), and (2) educational attainment, classified as High school or below versus College graduate or above. Physical activity level was evaluated using the WHO Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ), with activity quantified in metabolic equivalent minutes (MET × min). Health status indicators included body mass index (BMI), cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. For sensitivity analyses, anemia was defined using sex-specific hemoglobin thresholds (< 130 g/L for men, < 120 g/L for women). Anemia treatment status was assessed through self-reported responses to the question: ‘During the past 3 months, have you been on treatment for anemia, sometimes referred to as “tired blood” or “low blood”?’

Statistical analysis

To accurately reflect the complex sampling design of NHANES, our statistical analysis incorporated sampling weights, stratification, and clustering. In addition, we grouped participants based on quintiles of HRR for the description of baseline characteristics. Continuous variables were presented as mean standard error(SE), and categorical variables were presented as number (percentage). For the comparison of groups, the design-based Kruskal-Wallis test was conducted for continuous variables. For categorical variables, Pearson’s chi-square test with Rao & Scott adjustment was applied to account for the complex sampling design. Weighted Cox regression was applied to investigate the relationship between HRR and all-cause mortality, cancer mortality, and cardiovascular mortality. The Hazard Ratio (HR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to reflect the association’s strength. The analysis included four progressive models: the first was an unadjusted model; the second was a model that adjusted for the main factors of the NHANES sampling design (age, sex, and race); and the third model included adjustments for age, sex, race, smoking status, and cardiovascular disease. The selection criteria for this model were based on the following principle: A variable was considered a key covariate if its introduction in the unadjusted model, or its removal from the fully adjusted model, resulted in a change of more than 10% in the regression coefficient for HRR. The last was model 4, which fully adjusted all the covariates considered: age, sex, race, alcohol use, smoking status, physical activity, income level, exercise level, education, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. In addition, we divided HRR into quintiles and evaluated the relationship between HRR and all-cause mortality, cancer mortality, and cardiovascular mortality using weighted Cox, and performed a trend test to assess whether this association showed a consistent trend with the increase in HRR level. To further capture the possible nonlinear relationship between HRR and all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality, this research conducted a restricted cubic spline analysis with full covariate adjustment and assessed the nonlinear relationship by the likelihood ratio test. The optimal number of knots for the RCS was determined based on minimum Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) values and nonlinearity conditions. After adjusting all covariates, we also performed a stratified analysis to investigate which factors may affect the association between HRR and all-cause mortality, cancer mortality, and cardiovascular mortality. Subgroup analyses considered age groups, sex, race, alcohol use, education, smoking status, income level, cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Using cycle as an ordinal categorical independent variable, regression analysis was employed to test the trend of mean HRR changes from 1999 to 2018. In addition, using the 1999–2000 cycle as the reference, the ‘svycontrast’ function in the survey package was used to compare the differences in mean HRR across periods. All analyses were conducted with R software version 4.3.1. A two-tailed P-value of less than 0.05 was deemed significant.

Results

Characteristics of participants

This cohort study included 28,825 participants and used HRR quintiles as the grouping criteria (Table 1). The analysis results indicate that participants in the high HRR level group exhibit the following characteristics compared to the low HRR level group: they tend to be younger, have a lower BMI, a higher percentage of males, and a greater likelihood of alcohol consumption and smoking. In addition, these participants typically exhibit higher income levels, lower prevalence of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes, along with increased Hb and red blood cell counts, reduced RDW, and lower platelet counts.

Association between HRR and mortality from different causes

Weighted Cox regression analysis was used to assess the relationship between HRR and all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality (Table 2). The analyses indicated that HRR demonstrated significant negative associations with all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality in both the unadjusted and adjusted models (p < 0.001). In the fully adjusted Model 4, the association between HRR and all-cause mortality was HR 0.19, 95% CI 0.14, 0.26; the association with cancer mortality was HR 0.19, 95%CI 0.09, 0.38; and the association with cardiovascular mortality was HR 0.18, 95%CI 0.10, 0.31. To more effectively compare the association between different levels of HRR and various mortality rates, we grouped participants based on quintiles of HRR. The results showed that in each model, with Q1 as the reference, HRR at the Q2-Q5 levels was significantly negatively correlated with each mortality rate. In Model 4, with Q1 as the reference, it was found that in the highest quintile group (Q5), the association between HRR and all-cause mortality was HR 0.47, 95%CI 0.40, 0.55; the association with cancer mortality was HR 0.51, 95%CI 0.37, 0.71; and the association with cardiovascular mortality was HR 0.43, 95%CI 0.32, 0.56.

Trend tests of association between HRR and mortality from different causes

After grouping participants based on the quintiles of HRR, we also conducted a trend test. The results in Fig. 2 showed a significant trend effect between HRR and all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality (p for trend < 0.0001). Taking the Q1 group as a reference, higher HRR levels corresponded with decreasing hazard ratios for all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality.

RCS analysis of the association between HRR and mortality from different causes

To further explore possible nonlinear associations between HRR and each mortality rate, we performed a weighted RCS analysis and adjusted for all covariates considered. The results in Fig. 3 indicate that the relationship between HRR and cardiovascular mortality is more likely to be linear (P-overall < 0.05, Non-linear = 0.329), and the associations with cancer and all-cause mortality are likely to exhibit an “L”-shaped association (P-overall < 0.05, Non-linear < 0.05).

Subgroup analysis of the relationship between HRR and mortality from different causes

We performed stratified analyses of the associations between HRR and specific mortality rates in multiple subgroups to explore the potential effects of different variables on these associations (Supplementary Tables S1-3). The results showed that the associations between HRR and all-cause and cancer mortality were robust across subgroups (p for interaction > 0. 05). However, it is noteworthy that the relationship between HRR and cardiovascular mortality had an interaction (p for interaction < 0. 05) across smoking status and whether or not a person had cardiovascular disease. We found that higher HRR had a stronger protective effect on non-smokers and patients with cardiovascular disease.

Temporal trends of HRR

The temporal trends of HRR are shown in Fig. 4 and Supplementary Tables S4-5. From 1999 to 2018, the HRR level decreased from 1.18 (95% CI, 1.16–1.19) to 1.07 (95% CI, 1.05–1.08), showing a significant overall decreasing trend (P for trend < 0. 0001). Specifically, HRR decreased from 1999 to 2016 and rebounded in 2017–2018. Using the mean HRR of the 1999–2000 cycle as a baseline, we observed a reduction in mean HRR from 1.18 to 1.07, and the difference was significant since 2009. Additionally, the trends in the mean HRR changes in different cycles of NHANES were analyzed and stratified by subgroups. In the gender stratification, HRR was higher among males than females from 1999 to 2018, with both showing a decreasing trend. By race and ethnicity, in the overall trend, HRR was highest among non-Hispanic White participants, followed by Other Ethnic Americans. Conversely, the mean HRR was lowest among non-Hispanic Black participants. Based on drinking status, participants who drank alcohol had higher HRR means. In terms of household income, HRR was generally higher in “Not poor” adults compared to “Poor” adults. Regarding smoking status, current smokers had a higher mean HRR than former smokers, while non-smokers had the lowest HRR. For educational attainment, participants with a high school education or less had similar mean HRR levels to those with a college degree or higher from 1999 to 2012. However, after 2013–2014, participants with a college degree or higher had higher mean HRR levels. In terms of comorbid disease stratification, those participants without cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes had higher mean HRR values than those with cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. All graphs indicate a general downward trend in HRR across all subgroups (p for trend < 0.0001), with variations in the steepness of decline among different groups.

Sensitivity analysis for the association between HRR and mortality from different causes

To fully assess the reliability of the study results, we designed three independent sensitivity analyses. The first sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Tables S6). focused on assessing the impact of long-term follow-up on study outcomes, and we selected participants from the cycle 1999–2010. The exclusion criteria were defined as follows: (1) participants whose cause of death was classified as accidental (V01-X59, Y85-Y86); and (2) individuals with a follow-up period shorter than two years, to ensure sufficient observation time. To further explore the impact of anemia, the study population was stratified based on anemia status and medication use. One group included participants with anemia or those recently treated with anti-anemic medications, while the other group consisted of individuals without anemia and with no relevant drug use. Using this stratification, we carried out the second and third sensitivity analyses (Supplementary Tables S7, S8). The results demonstrated a high degree of consistency: higher HRR levels were associated with a reduction in risks of all-cause, cancer-specific, and cardiovascular mortality.

Discussion

This study is the first to explore the association between HRR and all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular disease mortality using a large-scale cohort analysis. The results indicated a significant negative correlation between HRR and all three mortality rates. RCS analysis revealed that HRR had a linear relationship with cardiovascular mortality, while it had an “L”-shaped association with cancer and all-cause mortality. Subgroup analysis showed that the relationship between HRR and all-cause and cancer mortality remained stable across subgroups. However, in the case of cardiovascular mortality, high levels of HRR had a more significant protective effect on non-smokers and patients with cardiovascular disease. In addition, our analysis showed that from 1999 to 2018, HRR exhibited an overall downward trend, decreasing from 1.18 to 1.07, which warrants further attention. The results of this study emphasize that HRR may be a valuable new indicator for predicting mortality.

However, research on HRR is very limited. Previous research has shown that low levels of HRR are linked to poor prognosis in a variety of diseases29. Rahamim E and Xiaoye Yuan et al. discovered that a decrease in HRR quantile was linked to reduced survival in patients with heart failure19,30; Junhong Wang and colleagues carried out a retrospective cohort study on how HRR affects death rate in patients with atrial fibrillation with in-hospital sepsis and found that lower HRR was significantly linked to higher all-cause mortality25; Xiu et and colleagues studied 6,046 patients with coronary atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Their findings revealed that an HRR below 10.25 led to a 47% rise in all-cause mortality risk and a 47.9% increase in the risk of cardiac death31. Research conducted by Qu et al. has shed new light on the predictors of frailty in elderly patients with coronary cardiovascular disease. Their study, which included 233 participants, compared the predictive power of several physiological markers for frailty. The results demonstrated that HRR was a more effective indicator of frailty than either Hb or RDW32. In cancer research, HRR is a key biomarker initially proposed as a prognostic marker for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC)33 and subsequently applied to various types of cancer, including bladder cancer and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. It has subsequently been used in a variety of cancer types, including bladder cancer34 and squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck35. A lower HRR was significantly linked to poor overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with cancer36,37. All the above studies are consistent with our research conclusions. Thus, HRR, as a composite measure, provides a comprehensive perspective on red blood cell distribution and oxygen-carrying capacity, demonstrating its potential as a prognostic assessment tool.

Our results suggest that higher HRR levels are linked to a lower risk of death, and this relationship remained consistent across subgroups. Although the exact biological mechanism remains unclear, existing evidence suggests that higher HRR may play a protective role by reducing oxidative stress levels38,39, decreasing inflammatory responses23,40, and improving blood rheology41. Higher HRR levels may attenuate oxidative stress by enhancing hemoglobin-mediated antioxidant defense systems42 and maintaining cellular membrane integrity through reduced red blood cell heterogeneity43; chronic inflammation may be modulated by elevated HRR levels through dual mechanisms: enhancing hemoglobin’s capacity to bind and neutralize inflammatory mediators44 and reducing RDW, which is typically associated with inflammatory states45, thereby mitigating tissue damage; in addition, individuals with higher HRR demonstrate enhanced endothelial function, characterized by improved production of nitric oxide46. This leads to vasodilation47,48 and anticoagulation49, optimizing blood rheology and potentially reducing the risk of thrombosis and cardiovascular events. The protective effects of HRR may be more significant in individuals who have never smoked50,51. Furthermore, given the long-term downward trend in HRR, future research should concentrate on the potential causes of this trend and its impact on public health.

Strengths and limitations

Our study presents several strengths, including the use of the NHANES database, a large cohort with extended follow-up periods, ensuring data rigor and authenticity. The large sample size enhanced the reliability of the results, while the general population focus improved generalizability. By investigating HRR’s association with all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality, we provide a comprehensive understanding of HRR’s potential health impacts, thereby offering a robust scientific basis for our conclusions.

Several limitations of our study need to be acknowledged. As an observational study, our findings demonstrate associations between HRR and mortality outcomes rather than causal relationships. The assessment of HRR levels at a single time point limits our understanding of potential trajectories, necessitating future studies with repeated measurements for validation. Although our analysis accounted for a wide range of potential confounders, including lifestyle factors, chronic diseases, and demographic characteristics, some unmeasured variables may still exert confounding effects. Additionally, NHANES primarily samples non-institutionalized individuals from the general population, which may not fully represent patients with specific hematological conditions. While we have considered anemia status using WHO criteria and conducted sensitivity analyses stratified by anemia status, the database’s structure does not allow for detailed identification of patients with specific conditions such as bleeding disorders, coagulation disorders, or hematological malignancies. Future studies in populations with specific hematological conditions would be valuable to validate the relationship between HRR and Specific mortality.

Conclusions

This cohort research found that HRR may be an independent risk factor for all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality. Lower HRR was linked to a higher risk of cardiovascular death, with this association particularly pronounced in smokers and individuals without a history of cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, since HRR is measured through routine laboratory tests, it could be considered a valuable indicator that is easy, reliable, and cost-effective for identifying high-risk individuals in clinical practice. Further research is required to confirm these findings and explore the possible association between HRR and all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality.

Data availability

All survey data utilized in this research are available in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database, accessible at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.

Abbreviations

- HRR:

-

Hemoglobin-to-red blood cell distribution width ratio

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- Hb:

-

Hemoglobin

- RDW:

-

Red blood cell distribution width ratio

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- SE:

-

Standard error

- RCS:

-

Restricted cubic spline

- PIR:

-

Poverty income ratio

- NCHS:

-

National Center for Health Statistics

- NDI:

-

National death index

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

References

Aktas, M. K., Ozduran, V., Pothier, C. E., Lang, R. & Lauer, M. S. Global risk scores and exercise testing for predicting all-cause mortality in a preventive medicine program. JAMA 292(12), 1462–1468. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.12.1462 (2004).

Matsushita, K. et al. Epidemiology and risk of cardiovascular disease in populations with chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrols. 18(11), 696–707. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-022-00616-6 (2022).

Yan, F. et al. Association between the stress hyperglycemia ratio and 28-day all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis: A retrospective cohort study and predictive model establishment based on machine learning. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23(1), 163. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-024-02265-4 (2024).

Ho, J. E. et al. Protein biomarkers of cardiovascular disease and mortality in the community. J. Am. Heart Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.117.008108 (2018).

Gijsberts, C. M. et al. Hematological parameters outperform plasma markers in predicting long-term mortality after coronary angiography. Angiology 69(7), 600–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003319717743679 (2018).

Liu, J. et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio can predict clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer treated with nivolumab. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 33(8), e22964. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.22964 (2019).

Garcia-Casal, M. N., Pasricha, S. R., Sharma, A. J. & Peña-Rosas, J. P. Use and interpretation of hemoglobin concentrations for assessing anemia status in individuals and populations: results from a WHO technical meeting. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1450(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.14090 (2019).

Stucchi, M., Cantoni, S., Piccinelli, E., Savonitto, S. & Morici, N. Anemia and acute coronary syndrome: current perspectives. Vasc. Health Risk. Manag. 14, 109–118. https://doi.org/10.2147/vhrm.S140951 (2018).

Cattadori, G. et al. Heart failure and anemia: Effects on prognostic variables. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 37, 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2016.09.011 (2017).

Samuels, N. et al. Blood pressure in the first 6 hours following endovascular treatment for ischemic stroke is associated with outcome. Stroke 52(11), 3514–3522. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.120.033657 (2021).

Feng, X., Zhang, Y., Li, Q., Wang, B. & Shen, J. Hemoglobin to red cell distribution width ratio as a prognostic marker for ischemic stroke after mechanical thrombectomy. Front. Aging Neurosci. 15, 1259668. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2023.1259668 (2023).

Acosta, J. N. et al. Admission hemoglobin levels are associated with functional outcome in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Crit. Care Med. 49(5), 828–837. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0000000000004891 (2021).

Hinkel, J. M., Li, E. C. & Sherman, S. L. Insights and perspectives in the clinical and operational management of cancer-related anemia. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 8(Suppl 7), S38-55. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2010.0133 (2010).

Gauthier, I. et al. Impact of hemoglobin levels on outcomes of adjuvant chemotherapy in resected non-small cell lung cancer: The JBR.10 trial experience. Lung Cancer 55(3), 357–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.10.021 (2007).

Baumeister, P., Canis, M. & Reiter, M. Preoperative anemia and perioperative blood transfusion in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One 13(10), e0205712. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205712 (2018).

Fyles, A. W., Milosevic, M., Pintilie, M., Syed, A. & Hill, R. P. Anemia, hypoxia and transfusion in patients with cervix cancer: A review. Radiother. Oncol. 57(1), 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-8140(00)00245-0 (2000).

Wilson, M. J. et al. Long-term prognostic value of preoperative anemia in patients with colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg. Oncol. 26(1), 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2017.01.005 (2017).

Förhécz, Z. et al. Red cell distribution width in heart failure: prediction of clinical events and relationship with markers of ineffective erythropoiesis, inflammation, renal function, and nutritional state. Am. Heart J. 158(4), 659–666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2009.07.024 (2009).

Zhou, J. et al. Predictive value of the Hb/RDW ratio for the risk of all-cause death in patients with heart failure with different ejection fractions. Cardiology 149(3), 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1159/000536440 (2024).

Pascual-Figal, D. A. et al. Red blood cell distribution width predicts long-term outcome regardless of anaemia status in acute heart failure patients. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 11(9), 840–846. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjhf/hfp109 (2009).

Peng, F. et al. An increasing of red blood cell distribution width was associated with cardiovascular mortality in patients on peritoneal dialysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 176(3), 1379–1381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.08.030 (2014).

Arbel, Y. et al. Red blood cell distribution width and the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and all-cause mortality. A population-based study. Thromb. Haemost. 111(2), 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1160/th13-07-0567 (2014).

Krongsut, S. & Piriyakhuntorn, P. Unlocking the potential of HB/RDW ratio as a simple marker for predicting mortality in acute ischemic stroke patients after thrombolysis. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 33(9), 107874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2024.107874 (2024).

Xi, L. et al. Association of hemoglobin-to-red blood cell distribution width ratio and depression in older adults: A cross sectional study. J. Affect. Disord. 344, 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.10.027 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Relationship between the hemoglobin-to-red cell distribution width ratio and all-cause mortality in septic patients with atrial fibrillation: Based on propensity score matching method. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd9110400 (2022).

Coradduzza, D. et al. Assessing the predictive power of the hemoglobin/red cell distribution width ratio in cancer: A systematic review and future directions. Medicina (Kaunas) https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59122124 (2023).

Bhowmick, D., Sheridan, R. T. C., Bushnell, T. P. & Spalding, K. L. Practical guidelines for optimization and characterization of the beckman coulter CytoFLEX™ platform. Cytometry A 97(8), 800–810. https://doi.org/10.1002/cyto.a.23998 (2020).

Tan, B. T., Nava, A. J. & George, T. I. Evaluation of the beckman coulter UniCel DxH 800, beckman coulter LH 780, and abbott diagnostics cell-dyn sapphire hematology analyzers on adult specimens in a tertiary care hospital. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 135(6), 939–951. https://doi.org/10.1309/ajcp1v3uxeiqtsle (2011).

Chen, J. L. et al. The value of red blood cell distribution width, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, and hemoglobin-to-red blood cell distribution width ratio in the progression of non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One 15(8), e0237947. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237947 (2020).

Rahamim, E. et al. The ratio of hemoglobin to red cell distribution width: A strong predictor of clinical outcome in patients with heart failure. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11030886 (2022).

Xiu, W. J. et al. Hemoglobin-to-red-cell distribution width ratio is a novel predictor of long-term patient outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention: A retrospective cohort study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 726025. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.726025 (2022).

Qu, J. et al. Correlation analysis of hemoglobin-to-red blood cell distribution width ratio and frailty in elderly patients with coronary heart disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 728800. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2021.728800 (2021).

Sun, P. et al. The ratio of hemoglobin to red cell distribution width as a novel prognostic parameter in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A retrospective study from southern China. Oncotarget 7(27), 42650–42660. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.9516 (2016).

Yılmaz, A., Yılmaz, H., Tekin, S. B. & Bilici, M. The prognostic significance of hemoglobin-to-red cell distribution width ratio in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Biomark. Med. 14(9), 727–738. https://doi.org/10.2217/bmm-2020-0045 (2020).

Tham, T. et al. Evaluation of the prognostic utility of the hemoglobin-to-red cell distribution width ratio in head and neck cancer. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 275(11), 2869–2878. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-018-5144-8 (2018).

Yılmaz, A., Mirili, C., Tekin, S. B. & Bilici, M. The ratio of hemoglobin to red cell distribution width predicts survival in patients with gastric cancer treated by neoadjuvant FLOT: A retrospective study. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 189(1), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-019-02153-x (2020).

İlhan, A., Gurler, F., Yilmaz, F., Eraslan, E. & Dogan, M. The relationship between hemoglobin-RDW ratio and clinical outcomes in patients with advanced pancreas cancer. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 27(5), 2060–2067. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_202303_31577 (2023).

Pavri, R. S., Gupta, A. D., Baxi, A. J. & Advani, S. H. Further evidence for oxidative damage to hemoglobin and red cell membrane in leukemia. Leuk. Res. 7(6), 729–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/0145-2126(83)90066-8 (1983).

Varela-Carver, A., Parker, H., Kleinert, C. & Rimoldi, O. Adverse effects of cigarette smoke and induction of oxidative stress in cardiomyocytes and vascular endothelium. Curr. Pharm. Des. 16(23), 2551–2558. https://doi.org/10.2174/138161210792062830 (2010).

Yetişir, A., Sariyildiz, A., Türk, İ & Coskun-Benlidayi, I. Evaluation of inflammatory biomarkers and the ratio of hemoglobin-red cell distribution width in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors. Clin. Rheumatol. 43(6), 1815–1821. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-024-06963-y (2024).

Münzel, T. et al. Effects of tobacco cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and waterpipe smoking on endothelial function and clinical outcomes. Eur. Heart J. 41(41), 4057–4070. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa460 (2020).

Rifkind, J. M., Nagababu, E., Ramasamy, S. & Ravi, L. B. Hemoglobin redox reactions and oxidative stress. Redox. Rep. 8(5), 234–237. https://doi.org/10.1179/135100003225002817 (2003).

MacQuarrie, R. A. & Gibson, Q. H. Functional heterogeneity of the alpha and beta chains in the oxidation-reduction reaction of human hemoglobin. J. Biol. Chem. 246(2), 517–522 (1971).

Ganz, T. Anemia of inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med. 381(12), 1148–1157. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1804281 (2019).

García-Escobar, A. et al. Red Blood cell distribution width is a biomarker of red cell dysfunction associated with high systemic inflammation and a prognostic marker in heart failure and cardiovascular disease: A potential predictor of atrial fibrillation recurrence. High Blood Press Cardiovasc. Prev. 31(5), 437–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40292-024-00662-0 (2024).

Richardson, K. J., Kuck, L. & Simmonds, M. J. Beyond oxygen transport: Active role of erythrocytes in the regulation of blood flow. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 319(4), H866-h872. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00441.2020 (2020).

Gladwin, M. T. Hemoglobin as a nitrite reductase regulating red cell-dependent hypoxic vasodilation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 32(5), 363–366. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.f294 (2005).

Gow, A. J. Nitric oxide, hemoglobin, and hypoxic vasodilation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 32(6), 479–482. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.F299 (2005).

Spencer, B. L. et al. A pumpless pediatric artificial lung maintains function for 72 h without systemic anticoagulation using the nitric oxide surface anticoagulation system. J. Pediatr. Surg. 59(1), 103–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2023.09.019 (2024).

Tong, X. et al. Cigarette smoke exposure impairs β-cell function through activation of oxidative stress and ceramide accumulation. Mol. Metab. 37, 100975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2020.100975 (2020).

Makena, P. et al. Biomarkers of exposure and potential harm in two weeks of smoking abstinence: Changes in biomarkers of platelet function, oxidative stress, and inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24076286 (2023).

Funding

This study has no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.L. and Y.L. share co-first authorship, jointly conceptualizing the research, providing statistical expertise, analyzing and interpreting results, visualizing data, and drafting the initial manuscript. T.L. and F.G. ensured data integrity and analysis accuracy. Y.L. and K.H. played key roles in the final submission. K.H. conducted a comprehensive review and validation. All authors actively participated and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

During the execution of the study, we followed the Declaration of Helsinki, including its updates, or comparable international ethical guidelines to ensure that all research activities met ethical standards. The NHANES project, overseen by the NCHS, received thorough approval from the NCHS Ethics Review Board to guarantee that data collection and usage are legal and ethical. Given the secondary analytic nature of this study based on the NHANES database, and adhering to the STROBE guidelines to ensure the scientific validity and transparency of the data analyses, additional ethical approval was not required. Information on the status of ethical review approvals for the NHANES project can be obtained by visiting https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lai, T., Liang, Y., Guan, F. et al. Trends in hemoglobin-to- red cell distribution width ratio and its prognostic value for all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality: a nationwide cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 7685 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92228-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92228-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Independent effects of the hemoglobin-to-red blood cell distribution width ratio on 180-day mortality in critically ill patients with Gastrointestinal bleeding: analysis from the MIMIC-IV database

BMC Gastroenterology (2025)

-

Interpretable machine learning analysis of clinicopathological and immunonutritional biomarkers for predicting lymph node metastasis in gastric cancer

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

The interaction and joint effects of the hemoglobin-to-red cell distribution width ratio and the triglyceride-glucose index (TyG) on depressive symptoms among residents of Nanjing City, along with the mediating role of TyG: a population-based study of 181,752 participants

Translational Psychiatry (2025)