Abstract

Planning a safe and efficient global path in a complex three-dimensional environment is a complex and challenging optimization task. Existing planning algorithms are faced with problems such as lengthy path, too many inflection points and insufficient dynamic obstacle avoidance performance. In order to solve these challenges, this paper proposes a dynamic obstacle avoidance algorithm (MSF-MTPO) with multi-strategy fusion to achieve the least inflection point path optimization. Initially, an adaptive extended neighborhood A* algorithm is designed, which dynamically adjusts the neighborhood extension range according to the distribution of obstacles around the current location, selecting the optimal travel direction and step size each time to reduce redundant paths and unnecessary extended nodes. Then, combined with the two-way search mechanism, starting from the original starting point and the end point, the opposite current node is searched as the target point, respectively, so as to reduce the number of search nodes and reduce the search time. In order to further improve the path efficiency, an inflection point trajectory correction method is designed to eliminate redundant inflection points on the premise of ensuring path safety. Fourthly, in order to solve the problem of path deviation or excessive softening caused by the limited path control points in existing smoothing methods, a local tangent circle smoothing method is proposed, which effectively improves the smoothness of the trajectory on the basis of retaining the superiority of the original path. Finally, the global optimization path is used as the guiding trajectory of artificial potential field method to avoid falling into local optimum and realize dynamic obstacle avoidance. In addition, the performance is compared with several advanced algorithms in different environments, and the MSF-MTPO algorithm has the lowest path cost in different complex scenarios, which proves the effectiveness and stability of MSF-MTPO in UAV 3D path planning.

Similar content being viewed by others

The rapid development of UAV technology makes it show great application potential and advantages in the fields of battlefield reconnaissance1, logistics and distribution2, environmental monitoring3and emergency rescue4, especially in military and disaster rescue. UAVs have become an indispensable key tool due to their high efficiency and autonomy. Quad-rotor UAV is suitable for short-range flight and high-timeliness tasks due to its simple structure, strong maneuverability and convenient operation5. However, with the increasingly complex mission environment, existing path planning algorithms6face problems such as too long paths and too many turns, which significantly affect the flight efficiency and resource consumption of UAVs7, making path planning one of the key bottlenecks in UAV applications.

UAV path planning can be regarded as a multi-objective optimization problem, which considers safety8, timeliness, obstacle avoidance, energy consumption9and flight distance in a complex environment10,11while finding the optimal or approximate optimal path. Existing path planning algorithms can be divided into five categories: graph search algorithms, optimization-based algorithms, sampling-based algorithms, local planning algorithms, and deep learning and reinforcement learning algorithms.Graph search algorithms (such as A*12, Dijkstra13, BFS14, and DFS15) rely on node expansion and cost evaluation, often incorporating heuristic functions to guide the search process. These algorithms are suitable for static environments and can find near-optimal global paths. However, when handling large-scale problems, such approaches typically face high computational complexity and may become trapped in local optima. Optimization-based algorithms (such as genetic algorithm16, particle swarm optimization17, ant colony algorithm18) have strong global search ability and adaptability by simulating evolution or swarm cooperation behavior, but their computational overhead is large, and the convergence speed is slow in high-dimensional space, which is easily affected by parameter tuning. Sampling-based algorithms (such as PRM19, RRT20) generate sample points through random or specific rules, which are suitable for the processing of high-dimensional complex environments and can effectively avoid some local optimal problems, but there are still challenges in environment modeling and sample generation. Local planning algorithms (such as the Artificial Potential Field method21, DWA algorithm22) focus on real-time response to dynamic environments and possess high computational efficiency. However, such methods are typically suitable only for local path optimization and may result in local optimal solutions. Deep learning and reinforcement learning algorithms (such as deep Q-learning23and policy gradient methods24) optimize path planning through model learning, and are suitable for high-dimensional and complex dynamic environments. Nevertheless, these methods have high requirements for the quality of training data and computational resources, and the training process is relatively lengthy.

In this context, scholars have proposed various improvement methods. For example, Li et al.25proposed an improved A* algorithm that integrates the dynamics and control characteristics of quadrotor UAVs26,27, designing a new heuristic evaluation function and obstacle penalty mechanism. The improved algorithm is capable of generating paths that align better with the flight characteristics of UAVs. However, this method does not fully account for the impact of environmental changes, which can limit the applicability of path planning results in dynamic environments. Yuan et al.28 proposed a path planning method based on an improved lazy \(\theta\)* algorithm. This method dynamically adjusts the heuristic weights based on the distance between the current node and the target node, effectively balancing search accuracy and speed. Additionally, the algorithm reduces redundant nodes by checking whether obstacles exist between nodes, thus improving search efficiency. Despite using an octree map to reduce the number of search nodes, the algorithm’s computational complexity remains high as the map size increases.Liao et al.29 integrated an adaptive A-star and an improved DWA path planning method, enhancing search efficiency by introducing adaptive weights and removing redundant points. The improved DWA algorithm added functions and optimized the path, making the planning results more reasonable. However, this method also does not consider the avoidance of dynamic obstacles, limiting its application in complex dynamic environments with moving obstacles.

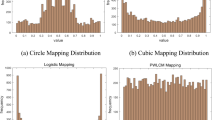

Bionic optimization algorithm has become a popular method in path planning today30,31.Zhou et al.32 proposed a UAV path planning model based on an improved Gray Wolf Optimizer (GWO) algorithm. Compared to the traditional GWO algorithm, the NI-GWO algorithm introduces a nonlinear convergence coefficient mechanism, which enhances the algorithm’s global search capability in the early iteration stages, while improving local search accuracy in the later stages, thus accelerating the convergence process. Lyu et al.33 proposed an improved Dung Beetle Optimization (IDBO) algorithm, which enhances population diversity by initializing the population using cubic chaotic mapping. Additionally, a new global search strategy is introduced to improve information exchange and global search capabilities. By applying adaptive t-distribution disturbances, the algorithm balances exploration and exploitation, enhancing local search ability. However, in certain cases, the algorithm may still fall into local optima. Fan et al.34 proposed an improved North Owl Optimizer (MINGO) algorithm with multi-strategy fusion. The MINGO algorithm integrates Levy flight strategy, Brownian motion strategy, enhanced exploration strategy, and Cauchy mutation strategy, improving the original NGO algorithm in terms of population diversity, exploration efficiency, balance between local and global search, and algorithm stability, thus enhancing its optimization performance. However, compared to other metaheuristic algorithms, MINGO has higher computational complexity and may become a bottleneck when handling large-scale problems. Liu et al.35 proposed a UAV path planning method based on the improved Porcupine Optimization (ICPO) algorithm. This method ensures population diversity through a high-quality point set population initialization strategy, thereby improving the algorithm’s search ability. The ICPO algorithm combines visual and auditory defense mechanisms to balance exploration and development, and helps the algorithm escape from the local optimal solution through a periodic retreat strategy, thereby enhancing the global search capability. However, the parameter setting of the ICPO algorithm mainly relies on experience and experimental adjustment, and lacks theoretical guidance.You et al.36 proposed an improved multi-strategy fusion whale algorithm (IWOA), which effectively balances the relationship between global search and local search through differentiated dynamic weighting in the search strategy. During location updates, the search capabilities are further enhanced by combining dynamic thresholds with an adaptive golden sine strategy. However, the method is computationally inefficient in complex scenarios and does not consider dynamic programming in dynamic environments. He et al.37 proposed an improved chaotic sparrow search algorithm (ICSSA). The algorithm uses piecewise chaotic mapping to initialize the population, improved sine-cosine algorithm to optimize the scavenger update, and dynamic boundary lens imaging reverse learning strategy, which improves the population diversity and global convergence, and effectively avoids falling into the local optimal solution. However, the choice of parameter p has a great influence on population distribution, and this research mainly focuses on global path planning, lacking further discussion on local path planning.Zhou et al.38 proposed the Multi-strategy Improved Snow Avalanching Optimizer (MISAO). Although the MISAO algorithm demonstrates excellent performance in solution accuracy and convergence speed, it still has certain limitations. In terms of time complexity, while it does not significantly increase compared to the original SAO algorithm, it may still be relatively high when dealing with large-scale complex problems.

Deep reinforcement learning has emerged as a frontier technology in the field of modern path planning. Li et al.39 proposed a dynamic value iteration network (DVIN) model based on the value iteration network (VIN). The model is trained using a scenario-based Q-learning algorithm and can generate a state value propagation function based on the connection information of UANET. However, the training time of the model is relatively long, and in practical applications, it is necessary to balance the efficiency of training and deployment.Yin et al.40 proposed the GARTD3 algorithm, which improves the autonomous navigation and obstacle avoidance capabilities of UAVs in complex three-dimensional environments with the help of guided attention mechanism and speed constraint loss function, and its performance is better than other deep reinforcement learning algorithms. However, the algorithm has some shortcomings: it is only suitable for static obstacle environment, and it has poor adaptability to complex situations such as dynamic obstacles, various obstacles and meteorological factors. The practical application effect and safety need to be verified, and due to the characteristics of deep reinforcement learning, the computing resource demand is large, which limits the practical application.The detailed introduction of various cutting-edge methods is shown in Table 1 below.

Although the above research has optimized a variety of algorithms, there are still some common problems, such as many redundant nodes in the path, long planning time in complex environment, and too long path. In addition, these algorithms also face the challenges of computational complexity and dynamic environment, so further improvements are urgently needed to overcome these limitations. Therefore, this paper proposes a dynamic obstacle avoidance algorithm for UAVs that combines adaptive extended neighborhood and inflection point minimization. The main contributions of this paper are as follows.

-

An adaptive extended neighborhood A* algorithm is proposed, which dynamically expands the neighborhood and selects the optimal direction and step size based on the distribution of obstacles around the current position. A bidirectional search mechanism is introduced, starting from both the initial and target points and performing searches toward the opposing current nodes as target points. This approach optimizes the search direction and significantly reduces the search time.

-

A path optimization method based on inflection points is proposed to plan a path with the least inflection points while ensuring path safety.

-

A local tangent circle smoothing algorithm is proposed, which adaptively smooths the path according to the angle at the inflection point of the original path, and only smooths the two sides of the inflection point of the path, so as to keep the optimality of the original path as much as possible.

-

The global optimization path is taken as the guiding trajectory of the improved artificial potential field method, so as to avoid falling into the local optimal solution and realize dynamic obstacle avoidance.

The structure of this paper is arranged as follows: Section 2 introduces the improvement strategy in the initial generation phase of the path. Section 3 elaborates the improvement scheme for the inflection point optimization part. Section 4 presents the optimization strategy for the path smoothing phase. In Section 5, combined with global trajectory optimization, a scheme of fusion improved artificial potential field method for dynamic obstacle avoidance is proposed. Section 6 systematically describes the core content of the MSF-MTPO algorithm through pseudocode and flowcharts. In Section 7, firstly, the static simulation experiments of eight algorithms are compared and analyzed, and then the algorithm in this paper is tested experimentally in dynamic environment. Section 8 summarizes the full text and looks forward to future research directions.

Adaptive neighborhood bi-directional A * algorithm

Adaptive neighborhood A* algorithm

The path length planned by the A* algorithm can be expressed as:

In the formula, L is the final path length, \(d\left( p_i,p_{i+1}\right)\) is the Euclidean distance from node \(p_{i}\) to node \(p_{i+1}\) and n is the number of nodes on the path.

Under the same heuristic function, the selected optimal nodes will be different due to the different search neighborhoods, which leads to the change of the final path length. Let the search range be R, and the path length is inversely proportional to the search range41, that is:

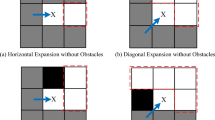

Equation 2 shows that a larger search range corresponds to a larger exploration space, thus having the opportunity to jump out of the local optimum, thus increasing the chance of finding a shorter path. Based on different search neighborhoods, an adaptive A * algorithm for neighborhood expansion is proposed, that is, the algorithm selects the optimal expansion node according to the current distribution state of obstacles. Let the current node coordinate be (x, y) and the obstacle be obs, and the extended node constraint is defined on the basis of eight-neighborhood search, as shown in Table 2:

Compared with the fixed four-neighborhood or eight-neighborhood, the adaptive neighborhood can dynamically adjust the extended neighborhood of the current point according to the distribution of current environmental obstacles, so as to plan the local optimal path. Under ideal environment, the path length of extended neighborhood search is reduced by 25.46%, 7.38% and 7.38% compared with four neighborhoods, eight neighborhoods and dynamically extended five neighborhoods42, respectively, and the number of inflection points also decreases. The four search neighborhood search paths are shown in the following Figure 1, where the orange square, green square, black square and gray square represent the starting point, end point, obstacle and search area respectively.

Bidirectional search

In complex environments or when the search space is large, unidirectional search requires traversing a large number of nodes to find the shortest path, especially when the target node is far from the starting point. Unidirectional A* needs to search within a very large space, resulting in high time and space complexity. To improve the search capability of the A* algorithm, this paper adopts a bidirectional search strategy, starting from the original starting point and the endpoint, and using the opposite current node as the target point for searching, thus optimizing the path-finding direction and shortening the search time.

Compared with the one-way A * algorithm, the following points need to be considered:

(1) The algorithm has two heuristic functions: the forward search heuristic function \(h_{start}(p_i)\) , which is used to evaluate the distance from the target node (target) to any node \(p_i\) ; and the reverse search heuristic function \(h_{target}(p_i)\) , which is used to evaluate the distance from the start node (start) to any node \(p_i\) .

(2) Consistency of the heuristic function:\(h_{start}(p_i)+h_{\textrm{target}}(p_i)=C\), where C is the actual minimum cost from the start point to the end point, ensuring that searches in both directions are based on the same estimated shortest path cost.

(3) Average of functions: If \(h_{start}(p_i)\) and \(h_{target}(p_i)\) are inconsistent, the inconsistency can be adjusted by taking the average value to form new heuristic functions \(P_{start}(p_i)\) and \(P_{target}(p_i)\) .

(4) Search termination condition: When the sum of the estimated distance from the starting node to the top node of the forward queue and the estimated distance from the target node to the top node of the reverse queue is greater than or equal to the known shortest path length of \(\mu\), the algorithm terminates the search. That is,

In the formula, \(h_{start}(top_{start})\)is the estimated distance from the starting node start to the foremost node \(top_{start}\) of the forward queue; \(h_{target}(top_{target})\) is the estimated distance from the target node target to the foremost node \(top_{goal}\) of the reverse queue;\(\mu\) is the shortest path length known. Let p(n) be a point of the final path \(\mu\) between the starting point start and the target point target, then the equation 5 is satisfied.

The final search planning path is shown in Figure 2.

Inflection point trajectory correction

When generating global paths, global planning algorithms (such as A*, RRT, genetic algorithms, and particle swarm algorithms) often encounter the problem of redundant path turning points, resulting in large path turning angles and a long overall path. Taking the four neighborhoods of the A* algorithm as an example, the planned path is shown in Figure 3 below:

The path generated by the A* algorithm contains five inflection points, as shown in Figure 3. In practical applications, the drone does not need to fly to the inflection point ① and then to inflection point ② in sequence, but can fly directly to inflection point ② because there are no obstacles on the path from the starting point to inflection point ②. Based on this, this paper proposes an inflection point trajectory correction method so that the planned path has the least number of inflection points. The specific steps are as follows:

Path representation

For the search path \(P=\{p_0,p_1,p_2,...,p_n\}\) , \(p_0\) is the starting point, \(p_n\) is the end point and \(p_i=(x_i,y_i,z_i)\) is the node on the path.

Inflection point calculation

Calculate the direction vector \(\vec {\nu }_i\) of the adjacent point on the path P :

For adjacent points \(p_i\) and \(p_{i+1}\) , calculate the angle \(\theta _{i}\) between their direction vector and the next direction vector:

In the formula, \(|\vec {\nu }_i|\) represents the magnitude of the i-th direction vector. Set the angle threshold \(\theta _{threshold}\) , if

Then \(p_i\) is considered to be the inflection point. Calculate each path point and obtain the set of inflection points \(T=\{t_1,t_2,...,t_m\}\).

Inflection point optimization

Add the starting point \(p_0\) and the end point \(p_n\) to the first and last positions of the inflection point set \(P_{new}=\{k_0,k_1,k_2,...,k_{m+1}\}\) respectively to form a new trajectory set.

Gradually connect the points in the set \(P_{new}\) , set the current starting point \(P_{current}=k_0\) , \(i=1\), \(P_{optimize}={k_0}\), check the line segment \(L(P_{current},k_i)\) :

If \(L(P_{current},k_i)\wedge obs=\emptyset\) (that is, the line segment does not pass through the obstacle), then \(i+1\) , \(k_i\) moves to the next point and rechecks whether the new line segment passes through the obstacle. If \(i=m+1\), then finally \(P_{optimize}=\{k_0,k_{m+1}\}\).

If \(L(x_{current},k_i)\wedge obs\ne \emptyset\) (that is, the line segment passes through the obstacle), then go back to the previous turning point, \(P_{current}=k_{i-1}\), \(P_{optimize}=\{P_{optimize},k_{i-1} \}\), and recheck whether the next line segment passes through the obstacle until \(P_{current}=k_{m+1}\) .

The final path can be expressed as the set of all line segments that do not pass through obstacles:

In the formula, \(L(k_j,k_{j+1})\) is the line segment that does not cross obstacles and \(L(k_j,k_{j+1})\wedge obs=\emptyset\), K is the number of optimized line segments. After optimizing the inflection point trajectory of Figure 3, the following Figure 4 is shown:

Local tangential circle smoothing

For the trajectory after correcting the inflection point, because the inflection point is sparse, conventional path smoothing algorithms, such as Bezier curve43 and spline interpolation, may cause the smoothed trajectory to intersect with obstacles. When the number of control points is insufficient, the degree of freedom of Bezier curve is limited, and each control point has a significant global influence on the curve, which leads to the deviation or excessive softening of the path between inflection points, which cannot meet the actual needs. Due to the large spacing between inflection points, spline interpolation may cause high-frequency fluctuations in the middle area, or generate too smooth shortcuts, further deviating from the actual path. These problems may cause smooth trajectories to intersect obstacles, thus reducing the effectiveness and safety of the path. The two smoothing trajectories are shown in Figure 5 below.

To address the above issues, this paper proposes a local tangential circle smoothing trajectory method, and the specific implementation steps are as follows: For each inflection point \(p_i\) \((i=1,2,...,n-1)\) on the trajectory \(P_{optimize}=\{p_0,p_1,p_2,...,p_n\}\) after the inflection point correction, let:

Then the angle \(\alpha\) at the inflection point \(p_i\) is:

The unit vector \(\vec {b}\) of the angle bisector at the inflection point \(p_i\) is:

For a circle whose center is on the angle bisector and tangent to the path at both ends of the inflection point, it satisfies:

The visualization diagram is shown in Figure 6 below:

For different x and \(\alpha\) , the radius of the circle tangent to the path is different, resulting in different trajectory smoothness. To ensure that one angle corresponds to only one smooth trajectory, define:

Combining equation 14, it follows that:

In the formula, r represents the radius of the circle whose center lies on the angle bisector and is tangent to the paths on both sides of the inflection point, \(\alpha\) is the angle at the inflection point \(p_i\) , and \(\lambda\) is the smoothing coefficient. From Figure 6, it can be seen that the distance from the center of the circle to the inflection point satisfies:

Therefore, the coordinates of the center of the circle are:

Use the arctangent function to calculate the polar angle \(\beta\) of the unit vector \(-\vec {b}=(x_{ct},y_{ct})\) pointing from the center of the circle to the inflection point.

From the sum of the interior angles of the triangle, we can get the arc angle to be \(\pi -\alpha\), so the range of the arc direction angle \(\varphi\) is:

By combining equations 16, 18 and 19, the smooth trajectory of the tangent circle at the inflection point \(p_i\) is obtained:

The trajectory is smoothed using a local tangent circle as shown in Figure 7,the smooth three-dimensional local tangent circle trajectory is shown in Figure 8.

Global optimization trajectory combined with artificial potential field method

Considering the influence of dynamic obstacles on UAV in real environment, the improved artificial potential field method is used to avoid local obstacles. The artificial potential field method (APF) regards the target position and the obstacle position as potential fields with attractive and repulsive forces, respectively. The gravitational force exerted by the target position on the UAV, while the obstacle exerts a repulsive force on the UAV, and the direction is far away from the obstacle. Under the combined action of attraction and repulsion, the UAV moves in the direction of the resultant force, thereby avoiding obstacles and advancing towards the target. Different from the traditional artificial potential field, increasing the gravity of the global optimization trajectory on the UAV can effectively guide the UAV to avoid obstacles while maintaining the superiority of the path, as shown in Figure 9.

Gravitational attraction of the target point

The current position of the UAV is \(p_i\) , the target position is \(p_n\) , and the attractive potential field function of the target point \(U_{att\_tar}\) is:

In the formula, \(\eta _{tar}\) is the attractive gain coefficient of the target point. The gradient of the attractive potential field is:

Repulsive force of obstacles

Assuming the obstacle position is \(p_{obs}\), the repulsive potential field function \(U_{rep}\) is:

In the formula, \(d_0\) is the maximum influence range of the repulsive force. The gradient of the repulsive potential field is:

Trajectory attraction

Trajectory attractive potential field function \(U_{att\_tra}\) :

In the formula, \(\eta _{tra}\) is the trajectory attraction gain coefficient, \(p_{tra}\) is a point on the trajectory, and \(d_1\) is the maximum influence range of the trajectory attraction. The gradient of the trajectory potential field is:

The resultant force potential field and resultant force gradient are:

The final resultant force of \(p_i\) at the current position is:

The improved artificial potential field method can effectively reduce the possibility of falling into local optimum by introducing trajectory gravity. However, in the area with narrow obstacle distribution, local oscillation may still be caused by the interaction between attraction and repulsion. In this paper, the low-pass filtering strategy is used to smooth the resultant force, which makes the path more continuous. Let the coefficients of the low pass filter be \(\omega\), resultant force after filtering:

Algorithm flow

The main program of the adaptive neighborhood and inflection point minimization UAV dynamic obstacle avoidance (MSF-MTPO) algorithm is based on A * algorithm global path planning and artificial potential field method local obstacle avoidance. The specific steps are as follows: (1) Using bidirectional A * algorithm and adaptively expanding the neighborhood according to the distribution of obstacles at the current position, selecting the optimal direction and step size, and planning the initial global trajectory; (2) optimizing the inflection points of the global trajectory planned by the improved algorithm, eliminating redundant inflection points, so that the path has the least number of inflection points under safe conditions; (3) For the path with redundant inflection points eliminated, the local tangential circle smoothing algorithm is used to smooth the path, and the superiority of the original path is retained; (4) The global optimization trajectory is taken as the guide trajectory of artificial potential field method, so as to avoid falling into the local optimum value and realize dynamic obstacle avoidance. The pseudo code and flow chart of the MSF-MTPO algorithm are shown in Table 3 and Figure 10:

Experimental analysis

Physical constraints

In order to obtain a feasible path, the UAV not only needs to consider the obstacles and target locations in the environment, but also must abide by its own physical constraints. These constraints include factors such as the maximum yaw angle, pitch angle44, flight speed45,46, flight altitude, as well as factors such as battery endurance. These physical constraints limit the maneuverability of the UAV and the flexibility of path planning. These factors must be taken into account when designing the path planning algorithm to ensure that the UAV can complete its mission safely.

Maximum yaw angle and maximum pitch angle

The maximum yaw angle and maximum pitch angle are used to limit the turning angle and climbing/diving angle of the drone. Set the coordinates of waypoint i to \(p(i)=(x_i,y_i,z_i)\) ,

The maximum yaw angle is \(\phi _max\), the maximum pitch angle is \(\varphi _max\), and the planned path should meet th following constraints:

Flight speed limitation

The maximum flight speed of the UAV is influenced by multiple constraints, including dynamic pressure (\(V_{max-q}\)), normal load factor (\(V_{max-n}\) ), normal load factor considering the angle of attack (\(V_{max-nz}\) ), and turn radius ( \(V_{max-Q}\)). The minimum speed (\(V_{min}\) ) must ensure stable flight in the air, where the lift must equal the gravity.

During the movement, the flight speed should meet the following conditions:

Cost function

The cost function47,48 is an important indicator for evaluating the performance of the improved algorithm. The UAV path planning aims to complete the task at the lowest cost. The cost in this article is as follows:

In the formula, J , \(J_1\) , \(J_2\) , \(J_3\) and \(J_4\) represent the total path cost, path length cost, height cost, turning angle cost, and safety cost, respectively. \(\alpha _1\) , \(\alpha _2\) , \(\alpha _3\) and \(\alpha _4\)are the cost coefficients49 for each, and their sum is 1.

Length cost

High cost

The stable altitude of the drone when flying can effectively save energy and ensure safety. In addition, when flying at low altitude, it can effectively avoid unknown threats by using ground cover50. Thus, the height cost is:

Corner cost

The maneuverability and stability of the UAV are limited by the maximum turning angle between two adjacent waypoints. In addition, frequent turns reduce flight efficiency, so the corner cost in this paper is:

Safety costs

An excellent path must first ensure its safety, that is, stay as far away from obstacles as possible. In order to quantify this security, this paper introduces the concept of security cost, which is specifically defined as:

The dimensions of each cost function are different, so it is necessary to normalize each cost:

Where i is the cost type (\(i={1,2,3,4}\) ), j is the type of comparison algorithm, and k is the total number of comparison algorithms. The final path cost of each algorithm is:

Experimental environment setup

Based on the above algorithm design, the simulation experiment was carried out on a notebook computer equipped with Intel ® Core ™i5-9300H processor and 16GB of memory, the operating system is Windows 10, and the programming environment is MATLAB R2023a.

Static scene

In order to evaluate the performance of the algorithm proposed in this paper, its results are compared with the following algorithms: Conventional A * algorithm, Improved A * algorithm (Improved A *) in reference25, BA algorithm, improved WOA algorithm (IWOA) in reference36, improved SSA algorithm (ICSSA) in reference37, improved SAO algorithm (MISAO) in reference38,Improved RRT algorithm (Improved RRT) in reference51and improved particle swarm optimization algorithm (Improved PSO) in reference52.Each algorithm has trajectory planning under different maps and different number of obstacles, and the algorithms participating in the comparison are simulated and tested with their paper parameters to analyze the performance of each algorithm under different maps and obstacles environments.

Static scene 1

Three test scenarios are set on a 20\(\times\)20\(\times\)20 3D map: Map 1 is a custom obstacle distribution, Map 2 and Map 3 are randomly distributed scenarios with 100 obstacles, and the obstacle heights in the three scenarios are randomly generated. The starting position of the drone is (2,2,3), and the target position is (19,19,10). The above algorithm is used for path search, and the path cost coefficients are set to 0.25. The visualization of each algorithm is shown in Figure 11, and the performance statistics are shown in Table 4.

Static scene 2

On a 3D map of size 50\(\times\)50\(\times\)20, three test scenarios are set: the number of obstacles in Map 4, Map 5 and Map 6 is 500 and randomly distributed, and the height is also randomly generated. The starting position of the drone is (2,2,3), and the target position is (49,49,15). The visualization of each algorithm is shown in Figure 12, and the performance statistics are shown in Table 5.

In two distinct scenarios, the original A algorithm and the improved A algorithm are compared. The algorithm proposed in this paper significantly enhances search efficiency by incorporating bidirectional search and an adaptive neighborhood strategy. Specifically, the bidirectional search strategy theoretically enables exponential efficiency improvements by reducing the number of expanded nodes. Although the time required to process individual nodes slightly increases, the overall runtime efficiency of the improved algorithm is superior. At the data structure level, the algorithm combines hash tables with matrix indexing, effectively optimizing obstacle checking and path searching processes. However, the detection of meeting points may become a bottleneck for the algorithm’s runtime efficiency. The application of the adaptive neighborhood strategy allows the algorithm to dynamically adjust the search range based on real-time conditions in complex 3D environments. Moreover, the more complex the environment, the more pronounced the time-saving advantages of this strategy become. By adopting the inflection point trajectory correction method and comparing it with eight algorithms (including original A *, improved A *, improved RRT, improved PSO, ICSSA, BA, IWOA, MISAO), the results show that the number of trajectory inflection points planned by MSF-MTPO algorithm is reduced by 92.53%, 91.14%, 96.76%, 82.96%, 86.92%, 67.33%, 90.02%, 90.93% compared with other algorithms, respectively. Under the condition of ensuring safety, the algorithm effectively minimizes the number of path inflection points, thus reducing the total steering angle of the UAV, improving the path planning efficiency and reducing the resource consumption. In addition, combined with the local tangential smoothing strategy, the MSF-MTPO algorithm optimizes the path length while retaining the superiority of the original path. Compared with the other eight algorithms, the trajectory length planned by this algorithm is reduced by 10.72%, 6.89%, 35.60%, 2.23%, 8.69%, 4.50%, 4.60% and 5.42%, respectively. Since the path corners are significantly fewer than other algorithms, the path planned by the MSF-MTPO algorithm in most complex environments has the smallest path cost, demonstrates excellent performance, and provides an efficient and stable solution for UAV path planning.

Static scene

In map 1 of static scenario 1, add obstacles with starting positions (6, 3, 4) and (9, 9, 3) with a radius of 0.5 m, a moving radius of 3 m, and a moving speed that varies randomly and ranges from (0, 1)m/s. The UAV parameter value settings are shown in Table 6, the dynamic obstacle avoidance visualization is shown in Figure 13.

After adding the dynamic obstacles, the planned trajectory is shown as the orange curve in the figure, and the actual trajectory is shown as the red curve. The path length is 29.6539 m, the minimum distance from the obstacle is 1.25 m, and the total steering angle is 632.59\(^\circ\).

Conclusion

In this paper, a new multi-strategy fusion method for UAV trajectory planning is proposed, which includes four stages: initial trajectory planning, trajectory optimization, trajectory smoothing and dynamic obstacle avoidance. In the initial planning stage, the traditional A * algorithm is improved by introducing a bidirectional search strategy and dynamically adjusting the search neighborhood according to the distribution of obstacles around the current node, which effectively improves the search efficiency and reduces redundant nodes. For the planned global trajectory, in order to minimize the inflection point of the trajectory, an inflection point trajectory correction method is introduced. The trajectory is regarded as a line segment composed of only the starting point, the end point and the inflection point, and whether there are obstacles between the two points is judged one by one, and the redundant inflection points that have not crossed the obstacles are eliminated until the corrected trajectory does not change, and finally a trajectory with the least inflection point is obtained. In order to smooth the modified trajectory, the local tangential smoothing method is used to smooth the trajectory, only on both sides of each inflection point, so as to keep the superiority of the original trajectory as much as possible and improve the smoothness of the trajectory. Finally, the global optimization trajectory is taken as the guide trajectory of the artificial potential field method, which increases the trajectory gravity. Since the guide trajectory has passed the global optimization, this not only ensures the generation of a better planning trajectory in the dynamic environment, but also significantly reduces the risk of falling into the local optimal solution. The simulation results show that in most scenarios, compared with the original A *, improved A *, improved RRT, improved PSO, ICSSA, BA, IWOA, MISAO and other eight algorithms, the proposed algorithm has the lowest trajectory planning cost, and the number of inflection points is greatly reduced, which reflects the superiority and robustness of the algorithm. However, it is worth noting that all the experimental environments used for trajectory planning in this paper are known environments and no real-world experiments have been conducted. Future work will focus on how to combine local information with artificial potential field method to achieve fast trajectory planning in unknown environments and test it in real environments.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the github repository, https://github.com/ximao123/MSF-MTPO/tree/master/pathdata.

References

Lee, M. et al. A study on the advancement of intelligent military drones: Focusing on reconnaissance operations. IEEE Access https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3390035 (2024).

Wu, Y. et al. Advanced uav material transportation and precision delivery utilizing the whale-swarm hybrid algorithm (wsha) and apcr-yolov8 model. Applied Sciences 14, 6621. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14156621 (2024).

Rufino, G., Conte, C., Basso, P., Tirri, A. E. & Donato, V. Mission design and validation of a fixed-wing unmanned aerial vehicle for environmental monitoring. Drones 8, 641. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones8110641 (2024).

Tang, P., Li, J. & Sun, H. A review of electric uav visual detection and navigation technologies for emergency rescue missions. Sustainability 16, 2105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16052105 (2024).

Tu, Y.-J. & Piramuthu, S. Security and privacy risks in drone-based last mile delivery. European Journal of Information Systems 33, 617–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2023.2214744 (2024).

Gautam, A., He, Y. & Lin, X. An overview of motion-planning algorithms for autonomous ground vehicles with various applications. SAE International Journal of Vehicle Dynamics, Stability, and NVH 8, https://doi.org/10.4271/10-08-02-0011 (2024).

Agrawal, J. & Arafat, M. Y. Transforming farming: A review of ai-powered uav technologies in precision agriculture. Drones 8, 664. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones8110664 (2024).

Zhou, S., He, Z., Chen, X. & Chang, W. An anomaly detection method for uav based on wavelet decomposition and stacked denoising autoencoder. aerospace 11, 393 (2024), https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace11050393.

Gao, N. et al. Energy model for uav communications: Experimental validation and model generalization. China Communications 18, 253–264, https://doi.org/10.23919/JCC.2021.07.020 (2021).

Rezaee, M. R., Hamid, N. A. W. A., Hussin, M. & Zukarnain, Z. A. Comprehensive review of drones collision avoidance schemes: Challenges and open issues. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2024.3375893 (2024).

Xia, J.-Y. et al. Metalearning-based alternating minimization algorithm for nonconvex optimization. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 34, 5366–5380. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2022.3165627 (2022).

Lv, Z. et al. Research on global off-road path planning based on improved a* algorithm. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 13, 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi13100362 (2024).

Zheng, W., Li, T., Jing, Q., Qi, S. & Li, Y. Real-time quantitative risk analysis and routing optimization of gaseous hydrogen tube trailer transport: A bayesian network and dijkstra algorithm combining approach. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 192, 1205–1220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2024.10.110 (2024).

Zhang, Y. & Xiao, Y. A comparison of the performance of graph breadth-first search algorithms based on openmp and cuda. In 2024 9th International Symposium on Computer and Information Processing Technology (ISCIPT), 307–311, https://doi.org/10.1109/ISCIPT61983.2024.10672800 (IEEE, 2024).

Zhou, X., Tang, H., Wu, S. & Wang, M. Enhancing artificial bee colony algorithm with depth-first search and direction information. International Journal of Wireless and Mobile Computing 27, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJWMC.2024.139616 (2024).

Debnath, D., Vanegas, F., Boiteau, S. & Gonzalez, F. An integrated geometric obstacle avoidance and genetic algorithm tsp model for uav path planning. Drones 8, 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones8070302 (2024).

Ye, Z., Li, H. & Wei, W. Improved particle swarm optimization based on multi-strategy fusion for uav path planning. International Journal of Intelligent Computing and Cybernetics 17, 213–235. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJICC-06-2023-0140 (2024).

Pu, X., Xiong, C., Ji, L. & Zhao, L. 3d path planning for a robot based on improved ant colony algorithm. Evolutionary intelligence 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12065-020-00397-6 (2024).

Bian, H., Li, W., Qi, M. & Chen, S. Unmanned surface vehicles path planning based on improved prm algorithm. In International Conference on Smart Transportation and City Engineering (STCE 2023), vol. 13018, 265–271, https://doi.org/10.1117/12.3024046 (SPIE, 2024).

Fusic, S. J. & Sitharthan, R. Improved rrt* algorithm-based path planning for unmanned aerial vehicle in a 3d metropolitan environment. Unmanned Systems 12, 859–875. https://doi.org/10.1142/S2301385024500225 (2024).

Yang, C., Pan, J., Wei, K., Lu, M. & Jia, S. A novel unmanned surface vehicle path-planning algorithm based on a* and artificial potential field in ocean currents. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 12, 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse12020285 (2024).

Li, P., Hao, L., Zhao, Y. & Lu, J. Robot obstacle avoidance optimization by a* and dwa fusion algorithm. Plos one 19, e0302026. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302026 (2024).

Deguale, D. A., Yu, L., Sinishaw, M. L. & Li, K. Enhancing stability and performance in mobile robot path planning with pmr-dueling dqn algorithm. Sensors 24, 1523. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24051523 (2024).

Fan, J., Zhang, X., Zheng, K., Zou, Y. & Zhou, N. Hierarchical path planner combining probabilistic roadmap and deep deterministic policy gradient for unmanned ground vehicles with non-holonomic constraints. Journal of the Franklin Institute 361, 106821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfranklin.2024.106821 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Improved a-star algorithm for power line inspection uav path planning. Energies 17, 5364. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17215364 (2024).

Abro, G. E. M. & Abdallah, A. M. A synergistic fractional-order control for precise helical trajectory tracking and formation stability in multi-agent quadrotor uavs. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-024-09849-y (2024).

Mohammadzadeh, A. et al. A non-linear fractional-order type-3 fuzzy control for enhanced path-tracking performance of autonomous cars. IET Control Theory & Applications 18, 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1049/cth2.12538 (2024).

Yuan, M.-S. et al. Improved lazy theta* algorithm based on octree map for path planning of uav. Defence Technology 23, 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dt.2022.01.006 (2023).

Liao, T. et al. Research on path planning with the integration of adaptive a-star algorithm and improved dynamic window approach. Electronics 13, 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13020455 (2024).

Mashru, N., Tejani, G. G. & Patel, P. Reliability-based multi-objective optimization of trusses with greylag goose algorithm. Evolutionary Intelligence 18, 25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12065-024-01011-9 (2025).

Tejani, G. G., Mashru, N., Patel, P., Sharma, S. K. & Celik, E. Application of the 2-archive multi-objective cuckoo search algorithm for structure optimization. Scientific Reports 14, 31553. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82918-2 (2024).

Zhou, X., Shi, G. & Zhang, J. Improved grey wolf algorithm: A method for uav path planning. Drones 8, 675. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones8110675 (2024).

Lyu, L., Jiang, H. & Yang, F. Improved dung beetle optimizer algorithm with multi-strategy for global optimization and uav 3d path planning. IEEE Access https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3401129 (2024).

Yang, F., Jiang, H. & Lyu, L. Multi-strategy fusion improved northern goshawk optimizer is used for engineering problems and uav path planning. Scientific Reports 14, 23300. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75123-8 (2024).

Liu, S., Jin, Z., Lin, H. & Lu, H. An improve crested porcupine algorithm for uav delivery path planning in challenging environments. Scientific Reports 14, 20445. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71485-1 (2024).

You, D., Kang, S., Yu, J. & Wen, C. Path planning of robot based on improved multi-strategy fusion whale algorithm. Electronics 13, 3443. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13173443 (2024).

He, Y. & Wang, M. An improved chaos sparrow search algorithm for uav path planning. Scientific reports 14, 366. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50484-8 (2024).

Zhou, C., Li, S., Xie, C., Yuan, P. & Long, X. Misao: A multi-strategy improved snow ablation optimizer for unmanned aerial vehicle path planning. Mathematics 12, 2870. https://doi.org/10.3390/math12182870 (2024).

Li, W., Yang, B., Song, G. & Jiang, X. Dynamic value iteration networks for the planning of rapidly changing uav swarms. Frontiers of Information Technology & Electronic Engineering 22, 687–696. https://doi.org/10.1631/FITEE.1900712 (2021).

Yin, Y., Wang, Z., Zheng, L., Su, Q. & Guo, Y. Autonomous uav navigation with adaptive control based on deep reinforcement learning. Electronics 13, 2432. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13132432 (2024).

Wang, X., Feng, Y., Tang, J., Dai, Z. & Zhao, W. A uav path planning method based on the framework of multi-objective jellyfish search algorithm. Scientific Reports 14, 28058. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79323-0 (2024).

Yang, W. Research on improved astar algorithm for path planning based on dynamic five-neighborhood search. China’s new technology and new products 1–4, https://doi.org/10.13612/j.cnki.cntp.2024.07.018 (2024).

Ji, G., Gao, Q., Zhang, T., Cao, L. & Sun, Z. A heuristically accelerated reinforcement learning-based neurosurgical path planner. Cyborg and Bionic Systems 4, 0026, https://doi.org/10.34133/cbsystems.0026 (2023).

Wu, X., Xu, L., Zhen, R. & Wu, X. Bi-directional adaptive a* algorithm toward optimal path planning for large-scale uav under multi-constraints. IEEE Access 8, 85431–85440. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2990153 (2020).

Yao, K., Li, J., Sun, B. & Zhang, J. An adaptive grid model based on mobility constraints for uav path planning. In 2016 2nd International Conference on Control Science and Systems Engineering (ICCSSE), 207–211, https://doi.org/10.1109/CCSSE.2016.7784383 (IEEE, 2016).

Shang, T. et al. Identification of aircraft longitudinal aerodynamic parameters using an online corrective test for wind tunnel virtual flight. Chinese Journal of Aeronautics 37, 261–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cja.2024.05.031 (2024).

Abro, G. E. M., Ali, Z. A. & Masood, R. J. Synergistic uav motion: A comprehensive review on advancing multi-agent coordination. IECE Transactions on Sensing, Communication, and Control 1, 72–88, https://doi.org/10.62762/TSCC.2024.211408 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Age of information based urllc transmission for uavs on pylon turn. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 73, 8797–8809. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2024.3358844 (2024).

Sun, G., Wang, Y., Yu, H. & Guizani, M. Proportional fairness-aware task scheduling in space-air-ground integrated networks. IEEE Transactions on Services Computing https://doi.org/10.1109/TSC.2024.3478730 (2024).

Ni, H. et al. Path loss and shadowing for uav-to-ground uwb channels incorporating the effects of built-up areas and airframe. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2024.3418952 (2024).

Xinyu, Y., Xie, W. & Cheng, W. Research on uav 3d path planning based on improved goal-bias rrt. Flight Dynamics 1–8, https://doi.org/10.13645/j.cnki.f.d.20241121.001 (2024).

Meng, Q., Qu, Q., Chen, K. & Yi, T. Multi-uav path planning based on cooperative co-evolutionary algorithms with adaptive decision variable selection. Drones (2504-446X) 8, https://doi.org/10.3390/drones8090435 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Key R&D Plan Project of Hubei Provincial Department of Science and Technology (Grant No.2022BEC008). South-Central University for Nationalities Key Laboratory of Cyber-Physics Fusion Intelligent Computing, State Ethnic Affairs Commission Open Fund(Grant Nos. CPFIC202402).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Longyan Xu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing - Review & Editing, Software. Mao Xi: Writing - Original Draft, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis. Ren Gao: Supervision, Editing, Funding Acquisition. Ziheng Ye: Writing - Review & Editing, Drawing. Zaihan He:Writing - Review & Editing, Data Curation.All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, L., Xi, M., Gao, R. et al. Dynamic path planning of UAV with least inflection point based on adaptive neighborhood A* algorithm and multi-strategy fusion. Sci Rep 15, 8563 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92406-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92406-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

An improved roosters algorithm for constrained 3D UAV path planning in urban environments

Scientific Reports (2025)