Abstract

Previous studies have yielded inconsistent findings regarding the comparison of lipid profiles in patients with primary aldosteronism (PA) and essential hypertension (EH), and there is a limited understanding of the association between plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC) and lipid profiles across various populations. 270 patients with PA and 598 patients with EH diagnosed at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University from January 2020 to June 2021 were consecutively included. After 1:1 propensity score matching by sex, age, and body mass index (BMI), 267 PA and 267 EH patients were ultimately enrolled in the study. The relationship between PAC and lipids was explored. Compared with EH patients, PA patients showed significantly lower levels of total cholesterol (TC) (P = 0.003), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) (P < 0.001) and non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (Non-HDL-C) (P = 0.014). Log TC (P = 0.0256), log triglyceride (TG) (P = 0.0497) and log Non-HDL-C (P = 0.0184) levels were negatively correlated with log PAC in PA patients. Consistently, these lipids yielded similar results with aldosterone/renin ratio (ARR). However, the correlation does not exist in EH patients. The levels of TC, LDL-C and Non-HDL-C were significantly lower in PA than in EH patients. And a significant independent inverse association between log TC, log TG, log Non-HDL-C, and log PAC levels in PA patients. However, the above associations were not always present in clinically matched EH patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dyslipidemia is an important risk factor for arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ACSVD). Dyslipidemia is closely related to diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, stroke, and peripheral arterial diseases1. Primary aldosteronism (PA) is considered the most common reason for secondary hypertension, and it accounts for approximately 10% of cases of hypertension patients2. Patients with PA were reported to be at greater risk of multiple end-organ damage, including atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, and renal sequelae, which can cause more damage than the degree of hypertension itself, compared to essential hypertension (EH) patients3,4. According to the relationship between PA and atherosclerosis5, a higher probability of alteration of lipid profiles might be observed in PA patients than in EH patients. However, data on differences in the alterations of blood lipid profiles in PA and EH patients are still inconclusive. Unexpectedly, several studies have shown that plasma total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels were significantly lower in patients with PA than in patients with EH6,7,8. However, other studies did not observe differences in lipid profiles between PA and EH patients9,10,11. In addition, some studies have demonstrated that high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels in PA patients were lower than those in EH patients2,8,12. In contrast, other studies found that HDL-C levels were higher in PA patients than in EH patients6,7. These observational studies suggested an interesting effect of plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC) on lipid profiles. However, no studies have explored the association between PAC and different lipid components and the possible influencing factors in the PA population. In the present study, based on comparing the lipid profiles of PA and EH patients, we analyzed in detail the association between PAC and lipid profiles. Our study provides clinical data on the effects of aldosterone on lipid profiles and provides a clinical reference for exploring the mechanisms of altered lipid profiles in patients with PA in the future.

Materials and methods

Subject source and grouping

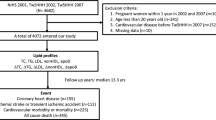

One thousand three hundred and fourteen hypertensive patients received PA screening in the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University from January 2020 to June 2021. The diagnostic procedure for PA was based on current guidelines13. Briefly, before admission, patients taking medications that affected ARR testing were required to stop or switch to verapamil and/or terazosin for 2–4 weeks. If hypokalemia was present, the patient’s potassium level was corrected before screening and confirmatory testing. Patients with an ARR larger than 30 (ng/dL)/(ng/mL/h) had their PA diagnosis confirmed using the captopril suppression test or saline infusion test. When diagnosing PA, we require patients to have an upright aldosterone level greater than 15 ng/dl unless the patient has very typical clinical signs of PA, such as persistent hypokalemia, refractory hypertension, and abnormal adrenal morphology. The diagnostic procedure for EH was based on current guidelines in China14. In total, 446 patients were excluded from the study, as they met one or more of the following exclusion criteria: (1) secondary hypertension other than PA; (2) taking statins, beta medicines, and other lipid-regulation drugs; (3) a diagnosis of uncontrolled heart failure (NYHA Grades III and IV), unstable angina, myocardial infarction and sick sinus syndrome, persistent atrial fibrillation, pulmonary heart disease, acute and chronic pulmonary infection, congenital heart disease, moderate-severe anemia, rheumatic valvular heart disease, uncontrolled hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, or malignant tumor within the past 3 months; and (4) drug abuse, cachexia and insanity. (5) Lacking baseline data. Two hundred and seventy patients with confirmed PA and five hundred and ninety-eight patients with confirmed EH were enrolled for 1:1 propensity score matching with the set caliper value as 0.02 by sex, age, and body mass index (BMI) as covariates. After propensity score matching, 267 PA patients and 267 EH patients were finally included in this study. All experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution or practice at which the studies were conducted, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University and was part of the study of the Nanchang Primary Aldosteronism Study (IIT-O-2021-032). It was registered on chictr.org (ChiCTR2200057297). Signed informed consent was obtained from each patient before participation.

General clinical data

Clinical data, such as age, sex, 24 h ambulatory blood pressure (Schiller Br-102 Plus Ambulatory BP Monitor), smoking history, alcohol drinking history, BMI, drug use, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia, were collected from all subjects. Smoking history was defined as: smoking more than 1 cigarette per day, at least 1 year, or 18 packs per year. Alcohol drinking history was defined as: on average, drinking alcohol at least two times a week for more than 1 year.

Biochemical indices

All blood biochemical indices were detected in the hospital’s central testing laboratory. The indices were as follows: electrolytes: blood potassium, blood sodium, and blood chlorine; renal function: serum creatinine (Scr) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR); blood glucose: fasting blood glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin; and blood lipids: TC, TG, LDL-C, and HDL-C. Non-HDL-C = TC − HDL-C. A completely automatic chemiluminescence immunoassay system (automatic chemiluminescence immunoassay analyzer 4000+ ; Shenzhen New Industries Biomedical Engineering Co., Ltd., Shenzhen China) was used to determine the plasma aldosterone concentration and plasma renin activity (PRA).

Dyslipidemia was determined with reference to current Chinese prevention and treatment guidelines for dyslipidemia15. High TC, high TG, low HDL-C, and high LDL-C were determined based on the following values: TC ≥ 6.2 mmol/L, TG ≥ 2.3 mmol/L, HDL-C < 1.0 mmol/L, and LDL-C ≥ 4.1 mmol/L, respectively. Dyslipidemia was defined as meeting any of the above standards. Diabetes mellitus was diagnosed based on the World Health Organization (WHO) diagnostic criteria for diabetes mellitus: fasting blood glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L and blood glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L 2 h after the oral glucose tolerance test or with current treatment with antidiabetics. The threshold of glycosylated hemoglobin to diagnose diabetes mellitus was defined as ≥ 6.3%.

Statistical methods

Propensity score matching (PSM) was applied to match patients in the EH and PA groups in a 1:1 fashion based on age, sex, and BMI, and the caliper was set as 0.02. Data on continuous variables meeting a normal distribution are expressed as the mean ± standard;/rd deviation, and those not meeting a normal distribution are expressed as the median and 25th and 75th percentiles. Classification and counting variables are expressed as the frequency and percentage of the total number. The rank sum test was applied to the quantitative data for intergroup comparison, and count or classified variables were assessed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Known related risk factors and confounding variables were included, and single-factor and multifactor regression analyses on PAC and each blood lipid component were performed with the statistical model. To perform data processing, the researchers used the statistical package R (The R Foundation; http://www.r-project.org; version 3.6.3) and Empower Stats software4.2 (www.empowerstats.net, X&Y solutions, Inc. Boston, Massachusetts).

Results

Baseline data of PA and EH patients

After 1:1 propensity score matching by sex, age, and BMI, 267 PA and 267 EH patients were ultimately enrolled in the study. As shown in Table 1, compared with the EH group, the TC (P < 0.003), LDL-C (P < 0.001) and Non-HDL-C (P = 0.014) levels were lower in the PA group, but the differences in TG (P = 0.366) and HDL-C (P = 0.349) levels were not statistically significant. Compared with the EH patients, the blood potassium (P < 0.001), PRA (P < 0.001) levels and eGFR (P = 0.004) were lower in the PA patients, whereas duration of hypertension(P < 0.001), using antihypertensive drugs(P < 0.001), blood sodium (P < 0.001), PAC (P < 0.001), ARR (P < 0.001), Scr (P = 0.048), 24-h mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) (P < 0.001), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) (P = 0.001) were higher. The sex, age, BMI, proportion of smokers, proportion of drinkers, medical history of diabetes, medical history of dyslipidemia, fasting blood glucose, and glycosylated hemoglobin were not significantly different between the two groups.

Correlation between blood lipids and PAC

Correlation analysis of blood lipids and PAC in all hypertensive patients

As shown in Supplemental Table 1, in the all hypertensive patients (PA and EH patients), no significant correlation was found between log PAC and log TC, log TG, log HDL-C, log LDL-C and log Non-HDL-C. After dividing the log PAC level into three equal parts (Q1-Q3), the P for the trend analysis was not statistically significant. Whether adjusting for sex, age, and BMI (Adjustment I) or further adjusting for sex, age, BMI, duration of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking history, drinking history, using antihypertensive drugs, blood potassium, eGFR, Fasting blood glucose, glycosylated hemoglobin, Standing PRA, 24 h mean SBP, 24 h mean DBP (Adjustment II), no significant correlation was noted between the blood lipids and PAC.

Correlation analysis of blood lipids and PAC in the PA and EH patients

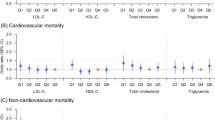

As shown in Table 2, in the PA patients, log TC (95% CI − 0.170, − 0.051; P = 0.0003), log TG (95% CI − 0.355, − 0.014; P = 0.0351), log LDL-C (95% CI − 0.218, − 0.042; P = 0.0040) and log Non-HDL-C (95% CI − 0.217, − 0.063; P = 0.0004) levels were significantly negatively correlated with log PAC. After adjusting for age, sex, and BMI (Adjustment I), the log TC (95% CI − 0.171, − 0.052; P = 0.0003), log TG (95% CI − 0.359, − 0.029; P = 0.0221), log LDL-C (95% CI − 0.220, − 0.046; P = 0.0031) and log Non-HDL-C (95% CI − 0.221, − 0.067; P = 0.0003) levels remained significantly negatively correlated with log PAC. After further adjusting for duration of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking history, drinking history, using antihypertensive drugs, blood potassium, eGFR, Fasting blood glucose, glycosylated hemoglobin, Standing PRA, 24 h mean SBP, 24 h mean DBP (Adjustment II), the negative correlations between log TC (95% CI − 0.142, − 0.010; P = 0.0256), log TG (95% CI − 0.352, − 0.001; P = 0.0497), log Non-HDL-C (95% CI − 0.191, − 0.018; P = 0.0184) and log PAC were maintained. Consistently, these lipids yielded similar results with ARR in Supplement Table 3. We further analyzed the stratified analysis and interaction between log TC, log TG, and log LDL-C with log PAC. As shown in Fig. 1, in general, the age, gender, BMI, smoking, alcohol, diabetes melitus, Using antihypertensive drugs, and eGFR stratification variables found no change in log TC, log TG, log Non-HDL-C and log LDL-C with log PAC associated with significant interactions between (all interaction P > 0. 05).

Subgroup analysis of PAC and blood lipid components in PA patients. BMI body mass index, EH essential hypertension, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, PA primary aldosteronism, PAC plasma aldosterone concentration, TC total cholesterol, TG triglycerides. PAC, TG, TC, HDL-C, and LDL-C were log-transformed with base 10. Adjusted for sex, age, BMI, duration of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking history, drinking history, using antihypertensive drugs, Blood potassium, eGFR, fasting blood glucose, glycosylated hemoglobin, standing PRA, 24 h mean SBP, 24 h mean DBP.

In contrast, in the EH patients, no significant correlation was found between log PAC and log TC, log TG, log HDL-C, log LDL-C and log Non-HDL-C. After dividing the log PAC level into three equal parts (Q1-Q3), the P for the trend analysis was not statistically significant. Whether adjusting for sex, age, and BMI (Adjustment I) or further adjusting for sex, age, BMI, duration of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking history, drinking history, using antihypertensive drugs, blood potassium, eGFR, Fasting blood glucose, glycosylated hemoglobin, Standing PRA, 24 h mean SBP, 24 h mean DBP (Adjustment II), no significant correlation was noted between the blood lipids and PAC.

Correlation analysis of blood lipids and PAC in the unilateral and bilateral PA patients

Two hundred and thirty-eight of 267 PA patients underwent adrenal vein sampling (AVS), of which 191 were successful bilaterally. The 191 patients with successful AVS were divided into unilateral PA (n = 111, 58%) and bilateral PA (n = 80, 42%) according to their results. As shown in the Supplement Table 5, there were no significant differences in total TC (P = 0.754), TG (P = 0.381), HDL-C (P = 0.813), LDL-C (P = 0.505) and Non-HDL-C (P = 0.630) between unilateral PA patients and bilateral PA patients.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study has the largest sample size in the research on the relationship between PAC and blood lipid profiles among populations with EH and PA. In this study, we explored the relationship between PAC and blood lipid profiles by comparing and analyzing blood lipid components between the PA population and EH population after matching for sex, age, and BMI, which may affect blood lipids. Some interesting findings were observed. (1) The levels of TC LDL-C and Non-HDL-C were lower in PA than in EH patients. (2) A significant independent inverse association between log TC, log TG, log Non-HDL-C, and log PAC levels in PA patients. However, the above associations were not always present in clinically matched EH patients.

In the general population, physiological PAC was previously shown to be positively associated with LDL-C and non-HDL-C and inversely associated with HDL-C16. In patients with metabolic syndrome and without PA, increased PAC was also shown to be related to increased TG and LDL-C levels and decreased HDL-C levels17,18. These studies suggested that aldosterone may be involved in the pathophysiology of metabolic syndrome and lipid metabolism disorders. However, significant associations between PAC and TC, TG, HDL-C, and LDL-C were not observed in the EH patients after correction for confounding factors in the present study. We do not yet know the reasons for the different associations between PAC and lipid composition in different studies. However, we also recognized the inconsistent results of studies comparing lipid composition levels in patients with PA and EH2,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Investigators quantified the subcutaneous fat and abdominal visceral fat area after abdominal CT scans in patients with PA and EH. They found that both the abdominal fat area and visceral fat area were lower in patients with PA than in patients with EH 19 .One possibility that the lipid composition of patients with proaldehydes decreases as aldosterone increases is that the precursor of aldosterone synthesis is cholesterol. Cholesterol is initially transported into the mitochondria via the steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein. Subsequently, the cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme (CYP11A1) catalyzes the cleavage of the cholesterol molecule’s side chain, generating pregnenolone—a precursor to all steroid hormones. Pregnenolone is then enzymatically transformed into progesterone within the smooth endoplasmic reticulum. Progesterone undergoes further modification through 21-hydroxylation by CYP21A2 in the mitochondria, resulting in the formation of 11-deoxycorticosterone (DOC). Finally, aldosterone synthase, which is encoded by the CYP11B2 gene, converts DOC into aldosterone. This process occurs in the zona glomerulosa cells of the adrenal cortex, facilitating the synthesis and secretion of aldosterone20,21. Another possible interpretation may be related to the liver X receptor (LXR), which is involved in cholesterol metabolism. Stimulation by LXR increases the accumulation of renin and cholesterol, but it is unclear whether the inverted induced effect will stimulate LXR22. Considering the different results among the different studies, specific circumstances, such as race, population, aldosterone levels, comorbidities, and treatment, should be considered when assessing the effect of aldosterone on lipid profiles.

Previous studies have primarily focused on comparing lipid profiles between populations with EH and PA6,7,8,9,10,11, neglecting investigations into the relationship between PAC and lipid profiles. A Korean study analyzed the association between aldosterone and lipid profiles in a general hypertensive population12; however, the study had a limited sample size and did not stratify further among EH and PA populations. This study revealed an increase in HDL-C and a decrease in TG with rising levels of PAC in the general hypertensive population. However, unlike the aforementioned study, we simultaneously observed a decrease in TC, TG and Non-HDL-C with increasing aldosterone levels in the PA population, with no association between HDL and PAC levels. Conversely, the EH population, with clinical characteristics similar to the PA population, did not exhibit this correlation. The differing associations between PAC and lipid profiles in EH and PA populations warrant further investigation into the underlying mechanisms.

Significantly lower levels of lipids and a negative correlation between PAC and lipid profiles in PA patients were unexpected findings taking into consideration the relatively high incidence of atherosclerotic events, metabolic syndrome, and insulin resistance in PA patients5. This indicates that increased atherosclerotic cardiovascular events in PA patients may not be a result of lipid profile changes. One possible reason is that PAC by directly acting on the mineralocorticoid receptor, damages the vascular endothelium and triggers an inflammatory response, thereby promoting the formation of atherosclerotic plaques and the progression of arterial stiffness. Additionally, PAC also contributes to the development of myocardial hypertrophy by enhancing inflammatory and fibrotic responses, ultimately leading to myocardial dysfunction20.Considering the specific lipid profile of PA patients and the potential influence of aldosterone on lipid composition, clarifying its clinical significance and related mechanisms is an important direction for future research.

The present study has several limitations. First, the mechanisms associated with the effect of PAC on lipid composition were not explored in this study, and the detection of LPL activity, LXR levels, and lipocalin levels may help to reveal the underlying mechanisms. Second, given the effect of increased PAC levels on oxidative stress and pro-inflammation, a comparison of oxidized low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (ox-LDL-C) between PA and EH patients and analysis of the association between PAC and ox-LDL-C in PA patients may provide more detailed information on the effect of PAC on lipid profiles. Third, apolipoprotein and lipoprotein a also play a certain role in cardiovascular events at present. However, in this study, data related to apolipoprotein and lipoprotein were not detected. Further research is needed to determine whether their high levels of apolipoprotein and lipoprotein contribute to cardiovascular events. Fourth, because cortisol levels and low-dose dexamethasone suppression trials were not performed in patients with PA, we could not exclude the potential impact of subclinical hypercortisolism on the data in this study. Finally, the lack of posttreatment follow-up data in PA patients prevented us from further analyzing the effect of antagonizing aldosterone or lowering aldosterone levels on the lipid profile of PA patients,further studies are needed. Nevertheless, our study may provide the most detailed analytical data on the relationship between PAC and lipid profiles in patients with PA. These data may provide a useful reference for future studies.

Data availability

De-identified patient data can be available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Catapano, A. L. et al. 2016 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias. Eur. Heart J. 37, 2999–3058. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw272 (2016).

Turchi, F. et al. Primary aldosteronism and essential hypertension: assessment of cardiovascular risk at diagnosis and after treatment. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 24, 476–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2013.09.009 (2014).

Milliez, P. et al. Evidence for an increased rate of cardiovascular events in patients with primary aldosteronism. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 45, 1243–1248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.015 (2005).

Monticone, S. et al. Cardiovascular events and target organ damage in primary aldosteronism compared with essential hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 6, 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30319-4 (2018).

Savard, S., Amar, L., Plouin, P. F. & Steichen, O. Cardiovascular complications associated with primary aldosteronism: a controlled cross-sectional study. Hypertension 62, 331–336. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01060 (2013).

Reincke, M. et al. Observational study mortality in treated primary aldosteronism: the German Conn’s registry. Hypertension 60, 618–624. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.197111 (2012).

Hanslik, G. et al. Increased prevalence of diabetes mellitus and the metabolic syndrome in patients with primary aldosteronism of the German Conn’s Registry. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 173, 665–675. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-15-0450 (2015).

Berends, A. et al. Primary aldosteronism is associated with decreased low-density and high-density lipoprotein particle concentrations and increased GlycA, a pro-inflammatory glycoprotein biomarker. Clin. Endocrinol. 90, 79–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/cen.13891 (2019).

Fallo, F. et al. Adiponectin and insulin sensitivity in primary aldosteronism. Am. J. Hypertens. 20, 855–861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjhyper.2007.03.012 (2007).

Matrozova, J. et al. Fasting plasma glucose and serum lipids in patients with primary aldosteronism: a controlled cross-sectional study. Hypertension 53, 605–610. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.122002 (2009).

Monticone, S. et al. Prevalence and clinical manifestations of primary aldosteronism encountered in primary care practice. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 69, 1811–1820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.01.052 (2017).

Moon, S. J., Jang, H. N., Kim, J. H. & Moon, M. K. Lipid profiles in primary aldosteronism compared with essential hypertension: Propensity-score matching study. Endocrinol. Metab. 36, 885–894. https://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2021.1012 (2021).

Funder, J. W. et al. The management of primary aldosteronism: Case detection, diagnosis, and treatment: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 101, 1889–1916. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2015-4061 (2016).

Chinese Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension (2018). The Chinese Cardiovascular Journal. 24:24–56. (2019).(in Chinese)

Junxian, Z., Runlin, G., Zhao Shuiping, Lu., Guoping, Z. D. & Jianjun, Li. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of dyslipidemia in China (2016). China Circ. Mag. 31, 937–953 (2016).

Hannich, M. et al. Physiological aldosterone concentrations are associated with alterations of lipid metabolism: Observations from the general population. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 4128174. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4128174 (2018).

Hannemann, A. et al. Association of plasma aldosterone with the metabolic syndrome in two German populations. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 164, 751–758. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-10-1074 (2011).

Musani, S. K. et al. Aldosterone, C-reactive protein, and plasma B-type natriuretic peptide are associated with the development of metabolic syndrome and longitudinal changes in metabolic syndrome components: findings from the Jackson Heart Study. Diabetes Care 36, 3084–3092. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-2562 (2013).

Beibei, Z. et al. Characteristics of the abdominal fat distribution profile in patients with primary hyperaldosteronism. Chin. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 834(5), 836–837 (2019).

Ekman, N. et al. Non-hypertensive effects of aldosterone. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26(2), 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26020540 (2025).

Wu, H., He, H., Han, T., Tian, X. & Zhu, Z. Targeting cholesterol-dependent adrenal steroidogenesis for management of primary aldosteronism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. S1043–2760(24), 00323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2024.12.001 (2025).

Maqdasy, S. et al. Once and for all, LXRα and LXRβ are gatekeepers of the endocrine system. Mol. Aspects Med. 49, 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2016.04.001 (2016).

Funding

The present study was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of China (32260214) and Jiangxi Provincial Department of Science and Technology Foundation of China (20212BAG70030).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yi-Fei Dong contributed to the conception and design of the study and revision of the manuscript. Ning-Peng Liang, Kun-Rui Rao, and Ming Hu collected the study data and wrote the manuscript. Ru-Yi Bao, Jian-Wei Liu, Hong-Jin Zhang, Huang Zhang, Meng-Bo Wu, and Xiang-Tao Zhang contributed to data collection and experiment. Ze-Qun Lai performed a statistical analysis of the study. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University and was part of the study of the Nanchang Primary Aldosteronism Study (IIT-O-2021-032). It was registered on chictr.org (ChiCTR2200057297). Signed informed consent was obtained from each patient before participation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, NP., Rao, KR., Hu, M. et al. The association between aldosterone and lipid profiles in patients with primary aldosteronism. Sci Rep 15, 8755 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92477-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92477-9