Abstract

Patients with acute cardiovascular disease require out-of-hospital care during the most critical and vulnerable periods of their illness. This study aims to evaluate the influence of musical intervention in patients with acute cardiovascular disease during transfer in Advanced Life Support (ALS) ambulances using an analytical randomized controlled case–control experimental study conducted according to CONSORT guidelines. Forty-one subjects took part in the study. The patients required the administration of nitrates/antiarrhythmics (n = 11, 26.8%), (n = 5, 12.2%) antiemetics, and (n = 7, 17.1%) opioids. Statistically significant differences were found for blood pressure and the variable cardiovascular drugs between groups. The use of music therapy to complement other health measures in ALS ambulances lowers blood pressure values and reduces the need to administrate cardiovascular drugs, thus avoiding their possible side effects. It is easy to implement, has a low cost and should be monitored and controlled as a specific nursing intervention, included in the care of patients transferred by ambulances on a routine basis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diseases of the cardiovascular system represent the main cause of mortality in the Spanish population with 121,341 deaths during 2022 (deaths by ICD-10 chapters), representing 26.1% of all deaths1. Ischemic heart disease, with 29,068 deaths, is the leading cause of death within this group, followed by cerebrovascular disease, with 24,6881. Diseases of the circulatory system were the main cause of hospitalization with 12.3% of the total in the year 20222. Prompt pre-hospital care, early diagnosis, treatment, as well as assisted and rapid transfer to an adequate hospital, influence the decrease in mortality in this group of diseases3. The investigation of music intervention as a healthcare complement for these groups may be beneficial.

The emergency services are characterized by providing urgent health care, to patients in critical health circumstances, at the place where the event occurs. This fact means that Advanced Life Support (ALS) ambulances are present when the patient presents a higher degree of stress and, therefore, where greater changes can be found at the physiological level. This is reflected in alterations in the vital signs, which can increase the pathophysiological effects, as the patient is placed in a hostile and unfamiliar environment, such as the ambulance cabin, surrounded by noises produced by the electromedical equipment and the circumstances of the transport itself (sirens, potholes, speed bumps, …)4,5. In a cabin with these characteristics, the patient may feel claustrophobic, an effect that can be enhanced by the limitation of movement generated by the anchoring of the seat belts to the stretcher and the lack of family support5.

The implementation of ALS ambulances is relatively recent in Castilla-La Mancha, hence research in this emerging field has been scarce in scientific production in the discipline of emergencies compared with other specialties in Spain6. Majority of study topics, according to the bibliometric impact of the European Journal of Emergency Medicine, focus on cardiology and the management of emergency services7, coinciding with the data obtained in the analysis of the 29 congresses of the Spanish Society of Emergency Medicine, between 1988 and 20178. Most of the studies reviewed on ALS ambulances and their assistance are related to the application and efficacy of different devices used in monitoring vital constants9.

Until 2011, patients with cardiovascular pathology in Castilla-La Mancha were transferred to the nearest hospital without considering other factors. In that year, the Coronary Reperfusion Code of Castilla-La Mancha (CORECAM)10 was implemented in the Castilla-La Mancha Health Service (SESCAM), covering 100% of the population 24 h a day. CORECAM is a regional, cross-cutting procedure coordinated by the Emergency Coordinating Centre, whose objective is the early detection of the acute coronary syndrome, immediate assistance and transfer to a suitable centre for percutaneous coronary intervention, with interlevel coordination being crucial due to the time-dependence of treatment.

The ICTUS Code11, implemented in 2015, is a regional and transversal procedure that seeks to provide access to cerebral reperfusion therapies in cases of acute ischaemic stroke.

The Emergency and Health Transport and Emergency Department (GUETS), which belongs to SESCAM, is in charge of managing healthcare at the scene of the incident and the transport of these patients, optimising initial care times, increasing the chances of recovery and reducing sequelae.

Therefore, the implementation of complementary interventions can significantly improve the quality of care in critical situations.

Throughout the nineteenth century, emerging psychiatry, led by Dr. Esquirol, supported music therapy to stimulate injured brains and as a distraction in the treatment of mania and alienation12. Likewise, Florence Nightingale, in her work “Notes on Nursing”, highlighted the benefits of music in patient care. She used it as part of her care for soldiers during the Crimean War, employing voice and flute sounds to provoke favourable effects on pain13.

Music, as a healthcare complement, is an intervention that is rarely used in the West as a reference, so it is not included in the conventional treatment of the disease. However, it is reflected as a nursing intervention in administering care, both by the Nursing Interventions Classification14, and the International Council of Nurses15.

Currently, music intervention in the hospital environment has shown benefits in the surgical16, oncological17, psychiatric field, intensive care units18, improving and normalizing physiological parameters19, and decreasing anxiety and pain in adult patients20, being a field that has not been studied in the prehospital setting.

The studies started in 14 hospitals in the Community of Madrid with the project "Music in vein”21,22, and the project to implement music in the ALS ambulances of the SUMMA 112 service in Madrid23, show the great scientific interest that currently exists in knowing the effects of music in the field of out-of-hospital emergencies.

The objective of this study is to observe the effects that music produces on physiological parameters, in patients with Acute Cardiovascular Disease (ACVD), and to determine its influence on the types of drugs administered during initial care. The intervention study is carried out in the ALS ambulance cabin during the time of transfer to the destination Hospital.

Material and methods

Study design

This pilot study was a randomized experimental of cases and controls on subjects with acute cardiovascular disease and/or symptoms, conducted according to CONSORT guidelines.

Study subjects

Patients who meet the inclusion criteria, which were, in addition to obtaining their informed consent: being of legal age, conscious and oriented in the time–space and person spheres with signs and symptoms ACVD and transferred in an ALS ambulance for at least 20 min.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria were: patients with non-physiological bradycardia, patients with severe sensory auditory deficiency, patients with psychiatric pathology, as well as all patients who refused to participate.

Sample

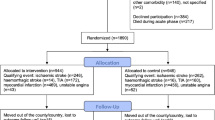

The intervention group underwent exposure to relaxing music with sounds from nature and the control group under the usual transfer conditions.

Patients were included in the pilot study through consecutive sampling during a 15-month period, from July to October. The random sequence for determining assignation to control or experimental group was created by a person from outside the study, who produced a series of consecutively numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes containing the allocation groups. Once the criteria for inclusion of the patient in the study were evaluated, the corresponding envelope was opened. The sample size (n) was calculated using Epidat 3.1 computer software, with a confidence level of 95% and a power of 80%, considering an effect size of 0.9 for the difference in means in two independent groups. With these data, the sample size of 21 subjects was established for each group.

Data collection

The study is carried out in the province of Cuenca (Spain), specifically, within the area of influence of the Motilla del Palancar ALS ambulance, attached to the GUETS. The scope of this resource corresponds to the territory covering Motilla del Palancar and a 30-min timing of the ALS ambulance’s distance by road. The geographical area of intervention of this unit is made up of 50 municipalities, 48 of them from the province of Cuenca and 2 from the province of Albacete, with a total population of 53,024 inhabitants and an area of 3816 km2 (13.9 inhabitants/km2). These data provide us with an overview of the idiosyncrasy of the study area, being a specific characteristic the great geographic dispersion and the low population density.

The care team consists of a nurse, a doctor, and two emergency health technicians. During the transfer, only the nurse and the doctor are in the medical cabin providing the patient with the appropriate medical care. The speed of the ambulance on country roads is according to Spanish traffic regulations.

In the case of physiological bradycardia, the patient is asked directly what his or her normal heart rate values are, and the patient’s previous reports are checked. The diagnosis is therefore based on the data obtained from the patient and the clinical judgement of the doctor and nurse who provide care from the beginning of the patient’s life.

In summary, the initial steps are as follows: the patient is transferred to the care cabin for transfer, the patient is accommodated on the stretcher and monitoring is completed. The nurse and doctor assess the inclusion criteria, and if they are met, informed consent is requested. If the patient agrees to participate in the study, the randomisation envelope is opened and the patient is assigned to the control or intervention group, as appropriate.

Data were collected with regard to demographic data (age and gender), medical diagnosis, systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP), heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR), partial oxygen saturation (SpO2), concentration of carbon dioxide at the end of exhalation (EtCO2), the pain perceived by means of the visual analogy scale (VAS) and the biespectral index (BIS) every 15 min during the transfer.

Data related to administered drugs were also collected, grouped into: nitrates/antiarrhythmics, opioids, antiemetics, benzodiazepines, tenecteplase, enoxaparin, furosemide, and ranitidine. To facilitate the collection and recording of data, the nursing report has been used, adding the items VAS, BIS and EtCO2, which, although routinely collected, are not mandatory in the nursing report.

Instrument

For the measurement of vital signs, a manual defibrillator of the Zoll® E-series brand was used. The ambient temperature was maintained at around 22–23 °C for comfort. Hypnosis and pain level data were obtained with the BIS VISTA™ Monitoring System.

The music system used was a BTS dynamic mini speaker, model MS109. The decibels were measured in the passenger cabin during the transfer, being in a range of 48.6–59.5 dB reaching a maximum of 73.1 dB when driving over a speed bump, and a maximum of 77.7 dB when putting on the sirens. Consequently, the volume was adjusted between 65 and 70 dB, to mask the usual sounds of the cabin.

Ambient music is chosen as it has the ability to address existing soundscapes and make unwanted sound, and specifically mechanically generated noise, less intrusive, while modulating the perception of the environment itself. It is therefore in tune with current trajectories in attention24.

Following the Benenzon model25, music is administered from natural sounds (running water, wind, birdsong), based on the Universal ISO that represents the acoustic sounds and energies common to all humanity, regardless of culture or specific environment.

Data analysis

Pilot studies are an important tool that provides critical information for the development and potential success of a subsequent larger trial. The analysis of pilot studies should be based on descriptive statistics and precision of estimates26.

The qualitative variables have been summarized using counts and percentages and the Chi-square test was used, calculating the p-value from a Monte Carlo test to ensure that the approximation conditions were met.

We have employed non-parametric Bootstrapping27, considering 1000 samples of the same size, for the estimation of the mean and standard deviation. This technique is very useful when working with small sample sizes where parametric assumptions may not hold true. For the comparison of the mean between the control and intervention groups, we used a t-test for independent samples. We consider significant differences when p < 0.05. The analyses were performed with R package.

Ethical issues

The study complied with all the local and regulatory requirements, with the ethical principles of biomedical research involving human subjects contained in the Declaration of Helsinki and was authorized by an independent Clinical Research Ethics Committee. This study has been identified by the Research Ethics Committee for Medicines (CEIm) under the Specialized Care Management of Toledo as number 266P. All patients gave their informed consent to participate in the study. Clinical Trial Registration Number: NCT05399927.

Results

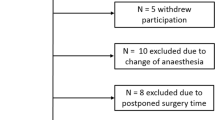

During the study period, all patients with ACVD were selected, fifty-six patients, of whom fifteen were excluded, leaving a total of forty-one patients for the final analysis (Fig. 1).

The subjects age ranged from 46 to 88 years, with a mean of 71.0 years and a standard deviation of 11.5 in the intervention group, and 72.7 (12.7) in the control group. n = 24, 58.5%, were males, 70.0% (n = 14) in control group, and 47.6% (n = 10) in intervention group. It was found that there were no significant differences according to sex and age with respect to the study groups (Table 1).

A total of 183 measurements were performed. The most common transfer time was 45 min, amounting to 4 measurements per patient, including the initial baseline measurement. Four measurements were made in 56.1% of the cases and five measurements in 24.4%. In the remaining cases a minimum of 3 measurements were taken (Fig. 2).

Regarding personal histories in the intervention group, it should be noted that 90.5% (n = 19) were diagnosed with hypertension, while 57.1% (n = 12) had dyslipidaemia, and 57.1% (n = 12) had diabetic mellitus. Table 1 shows the percentage of subjects per study group and their specific characteristics.

Regarding the treatment that was administered during the transfer to the hospital, the personnel of the ALS ambulance found that the drugs most administered intravenously were nitrates/antiarrhythmics 26.8% (n = 11), antiemetics 12.2% (n = 5) and opioids 17.1% (n = 7) (Table 1).

We also highlight the data obtained for the shock index, with a value of 0.9 (0.7) in the intervention group and 0.7 (0.3) for the control group (Table 1).

Table 2 shows the means (standard deviations) for the rest of the quantitative variables. For each of them, the mean, the minimum, and the maximum of all the measurements carried out on each patient have been taken into account, i.e., average measurements collects the average of all measurements made on the same patient, Minimum (Maximum) measurements collects the minimum (maximum) value observed on all measurements made on the same patient.

Table 3 shows the disaggregated results regarding whether or not nitrites/antiarrhythmics were administered in both the control and intervention groups.

Discussion

The pilot study population (N = 41) had similar demographic, personal and clinical variables in both groups, except for the previous diagnosis of hypertension. In the intervention group (n = 21), there were more hypertensive patients (p = 0.031) and consequently a higher consumption of antihypertensive drugs as usual treatment. No significant statistical differences were found for the other variables analysed. The shock index, as a tool for assessing severity28, whit a value of 0.7 control group and 0.9 in intervention group (Table 1), showed levels of mild shock in both groups. These data allow us to ensure the homogeneity of the study groups.

It was observed that vital signs data indicated a tendency to decrease or stabilize when the subject was exposed to music intervention, which is related to the data found in the study by Lorek29, whit a value of 0,7 control group and 0,9 in intervention group (Table 1). However, there is only statistical significance (p < 0.05), in blood pressure (BP) (Table 2), possibly due to the lack of significance, insufficient sample size and that the affected variables were within normal ranges.

Regarding the first, the mean SBP was reduced by 15.3 mmHg and the mean DBP by 9.6 mmHg with respect to the control group, in line with Do Amaral et al., who describe a 6 mmHg reduction in SBP values19. Our results reinforce those obtained in other studies in which a normalization of BP is observed, reducing both SBP and DBP in surgical processes30.

According to the literature consulted, exposure to music produces a decrease in anxiety associated with changes at a physiological level such as a decrease in BP30,31,32. Given the specific characteristics of the critical patient with cardiovascular pathology, being cared for care in an ALS ambulance, the priority is for healthcare team to intervene quickly and effectively, allowing for early haemodynamic stabilisation of the patient, as well as continuous monitoring and assessment, to address any potential aggravation of the clinical situation without delays. In our situation, self-administered scales and questionnaires were no not feasible for measuring anxiety levels; however, this decrease in BP has been reflected.

We could consider the administration of Nitrites/Antiarrhythmics as a confounding variable, given that its administration has the side effect of hypotension and an increase in HR, and therefore a decrease in BP in the intervention group. For this reason, the initial results have been revised by disaggregating according to whether the patients have received this confounding factor (Nitrites/Antiarrhythmics) or not, both in the control group and in the intervention group. The results reinforce the hypothesis of a normalising effect of the TAS and TAD figures in the intervention group (Table 3).

The values obtained from de HR variable (Table 2) indicate that the control group patients have lower levels compared to the experimental group, mean of 80.4 versus 85.1, respectively, suggesting a clear trend towards a decrease, similar results to other studies31,33, finding significance in studies conducted in the hospital surgical environment34 and intensive care patients35.

The RR measurement was performed with an electromedicine sensor, which reduces the measurement bias, with the difference in the RR means being 0.6 breaths per minute, the lesser effect could be attributed to the fact that the music is chosen by the researcher and not the patient36, and the time of exposure to music is less than in other studies in which the results obtained have been significant38.

The results obtained in the SpO2 variable coincide with the studies carried out in other clinical settings35,37. We have not found any studies that register the EtCO2 variable, consequently, the data cannot be compared.

Taking into account that one of the inclusion criteria is that the patient is conscious, the range in the BIS is narrowed. Values between 97 and 100 correspond to the awake, conscious, and active patient, taking the value of 90 as the patient’s state without anxiety. With these references, we observe that the mean of the control group is 93.0 (6.0), compared to the mean of 92.3 (7.4) in the intervention group, in accordance with the findings of Maeyama et al.38.

Several investigations have confirmed that music significantly reduces the perception of pain by the cancer patient39, in patients undergoing surgical procedure40,41, as well as in the hospital emergency setting, and in hospital intensive care units35,37, where a decrease in the administration of analgesic drugs was observed40.

The absence of significant VAS findings could be related to the low VAS levels found (mean of 1.1 vs. 1.2), both below 3, a value that some authors define in pain-free ranges42.

Given that there are currently no specific monitors for assessing and quantifying pain in critical patients, the BIS could be useful as an indirect indicator of pain in the patient43. In the literature reviewed, we have not found any studies that assess this data in conscious patients. However, the use of BIS is common monitoring in the ALS ambulance in which the study was carried out.

When studying the impact of music on the administration of drugs during care, we found in the literature that Ayoub et al.44, associate a decrease in the anxiety of patients with spinal anaesthesia exposed to music intervention and with this, lower doses of Propofol administration, these data coinciding with similar studies45. In this regard, studies stand out16,40,43 in which the doses of drugs administered as sedation prior to a surgical procedure are decreased, as well as the doses of analgesic drugs during different invasive procedures.

Regarding the administration of drugs during the transfer, it is worth highlighting the results obtained in relation to the variable that encompasses nitrates and antihypertensive drugs (p = 0.017), which implies that listening to music reduces the doses administered to these patients, a fact that acquires great relevance since interactions with other drugs and possible adverse effects could be avoided.

We were unable to compare these findings with other studies, since in general, the drugs that have been described in the different studies were related to the decrease in pain and anxiety, and not to treatments specifically related to drugs with a cardiovascular effect.

In the review carried out, there were no references to the effect of music on ALS ambulances, so the data obtained could not be compared with similar work environments.

Limitations

Our research has some limitations such as the size of the sample, due to a higher number of dropouts than expected, although is very near to the n recommended by Epidat programme. Therefore, it would be necessary to carry out clinical trials with a larger sample size to consolidate the results obtained in our pilot study.

We also believe it is important for future studies to record measurements of the parameters studied before introducing the patient into the ALS ambulance and to record the doses and route of drug administration.

Conclusions

We can conclude that the use of music in the passenger cabin during transfers in ALS ambulances can be useful as an adjunct to conventional treatment. It helps to normalize blood pressure values in ACVD patients by masking the noise inherent in ambulance transport and reducing the need for nitrate/antiarrhythmic administration, thereby minimizing potential side effects.

As a result of the results obtained in this pilot study, the GUETS, the institution where the study was carried out, has asked us for a procedure to implement music in the rest of the ALS ambulances, in order to continue studying the effect of music in this area. Furthermore, it is an intervention that is adapted and would be integrated into the Castilla-La Mancha Health Plan, Horizon 202546, within the chapter on the Humanisation of healthcare, whose objective is to promote care centred on people and their needs. This encourages the continuation of this line of research by conducting a more powerful clinical trial. In the absence of studies in which intervention with music is carried out in ALS ambulances, and assuming the multiple limitations it has, we could consider this pilot study as a source of new evidence for this setting.

Music intervention should be monitored and controlled as a specific nursing intervention, included in the care of cardiovascular patients transferred by ALS ambulances on a routine basis. Its implementation is easy, safe, and low cost.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Defunciones según la Causa de Muerte Primer semestre 2023 (datos provisionales) y año 2022 (datos definitivos). [internet]. Nota de prensa 19 diciembre 2023. [cited 2024 Oct 23]. Available from https://www.ine.es/prensa/edcm_2022_d.pdf (2024).

Instituto Nacional de Estadística. [internet] 2024. [cited 2024 oct 23]. Available from https://www.ine.es/dyngs/Prensa/es/EMH2022.htm (2024).

Miró, Ò. et al. Atención prehospitalaria a los pacientes con insuficiencia cardiaca aguda en España: Estudio SEMICA. Emergencias. 29(4), 223–230 (2017).

Delaney, L., Litton, E. & Van Haren, F. The effectiveness of noise interventions in the ICU. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 32(2), 144–149. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACO.0000000000000708 (2019).

Jiménez. M., G., & Castro Jiménez, R. A. Fisiopatología del transporte sanitario terrestre. Posiciones de traslado en las urgencias de Atención Primaria. Modulo IV. Movilización. Arp Producciones. Sociedad Andaluza de Médicos Generales y de Familia. [internet]. [cited 2024 april 14]. Available from https://sanmg.es/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/movilizacion_mod4-2.pdf (2021).

Fernández-Guerrero, I. M., Martín-Sánchez, F. J., Burillo-Putze, G. & Miró, Ò. Análisis comparativo y evolutivo de la producción científica de los urgenciólogos españoles (2005–2014). Emergencias. 29, 327–334 (2017).

Fernández-Guerrero, I. M., Martín-Sánchez, F. J., Burillo-Putze, G., Graham, C. A. & Miró, Ò. Analysis of the citation of articles published in the European Journal of Emergency Medicine since its foundation. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 26(1), 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000502 (2019).

Fernández-Guerrero, I. M. et al. Presentations at 29 conferences of the Spanish Society of Emergency Medicine (SEMES) from 1988 to 2017: A descriptive analysis. Emergencias 30(5), 303–314 (2018).

Pérez Regueiro, I. et al. Efficacy of the Boussignac continuous positive airway pressure device in patients with acute respiratory failure attended by an emergency medical service: A randomized clinical trial. J Emergencias 28(1), 26–30 (2016) (Spanish).

Llanos Val Jiménez, C., del Campo Giménez, M. & García Atienza, E. M. Actualización del Código de Reperfusión Coronaria de Castilla-La Mancha (CORECAM). Medidas de actuación en Atención Primaria. Rev. Clin. Med. Fam. 12(2), 75–81 (2019).

Código ICTUS. Estrategia de reperfusión en el ICTUS 2023, Castilla-La Mancha SESCAM. [Internet]. [cited 2024 may 14]. Avalaible from https://scmneurologia.com/files/codigo_ictus_clm_2023_maquetado_12b.0.pdf (2023).

La musicoterapia. Historia de la musicoterapia: la terapia que cura con la música. [Internet]. [cited 2024 May 7]. Available from: https://lamusicoterapia.com/historia-de- la-musicoterapia-la-terapia-que-cura-con-la-musica/ (2012).

Nightingale, F. Notas sobre enfermería: Qué es y qué no es (Elsevier Masson, 1995).

Butcher, H. K., Bulechek, G. M., Wagner, C. M. & McCloskey, J. Clasificación de intervenciones de enfermería (NIC) (Elsevier, 2018).

International Council of Nurses [Internet]. [cited 2023 december 12] Available from https://www.icn.ch/sites/default/files/inline-files/icnp2017-ic.pdf (2017).

Hole, J., Hirsch, M., Ball, E. & Meads, C. Music as an aid for postoperative recovery in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 386(10004), 1659–1671. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60169-6 (2015).

Xu, Z. et al. Effect of music therapy on anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 14, 16532. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66836-x (2024).

Xiao, M. et al. Efficacy and safety of music therapy for the treatment of anxiety and delirium in ICU patients: A meta-analysis and systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Minerva Anestesiol. 90(5), 439–451. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0375-9393.24.17900-X (2024).

Amaral, Do. et al. Effect of music therapy on blood pressure of individuals with hypertension: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 214, 461–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.03.197 (2016).

Kühlmann, A. Y. R. et al. Meta-analysis evaluating music interventions for anxiety and pain in surgery. Br. J. Surg. 105(7), 773–783. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10853 (2018).

Cultura en vena. Libro Blanco. Hoja de ruta para incorporar los MIR (Músicos Internos Residentes) en los entornos sanitarios. Siete Estudios clínicos. [internet] [cited 2024 october 23] Pág. 59–108. Available from https://culturaenvena.org/mir/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Libro-blanco-CeV-07.pdf (2022).

Morales-Betancourt, C. et al. Live music can play a major role in aiding the development of preterm infants in neonatal intensive care units. Acta Paediatr. 109(9), 1895–1896. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15191 (2020).

Las nuevas UVIs móviles del SUMMA 112 incorporarán música clásica durante los traslados [Internet]. [cited 2024 october 10]. Available from https://www.comunidad.madrid/noticias/2019/06/20/nuevas-uvis-moviles-summa-112-incorporaran-musica-clasica-traslados (2019).

Rossetti, A. Environmental music therapy (EMT): Music’s contribution to changing hospital atmospheres and perceptions of environments. Music Med. 12, 130–141 (2020).

Benenzon, R. Musicoterapia: de la teoría a la práctica. Ibérica P, editor. (2011).

Kunselman, A. R. A brief overview of pilot studies and their sample size justification. Fertil. Steril. 121(6), 899–901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2024.01.040 (2024).

Efron, B. & Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to the Bootstrap (Chapman and Hall, 1993).

Vakhshoori, M. et al. Impact of shock index (SI), modified SI, and age-derivative indices on acute heart failure prognosis; A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 19(12), e0314528. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0314528 (2024).

Lorek, M., Bąk, D., Kwiecień-Jaguś, K. & Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska, W. The effect of music as a non-pharmacological intervention on the physiological, psychological, and social response of patients in an intensive care unit. Healthcare (Basel). 11(12), 1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11121687 (2023).

Lee, H. Y., Nam, E. S., Chai, G. J. & Kim, D. M. Benefits of music intervention on anxiety, pain, and physiologic response in adults undergoing surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian Nurs. Res. 17(3), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2023.05.002 (2023).

Heidari, S. et al. The effect of music on anxiety and cardiovascular indices in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft: A randomized controlled trial. Nurs. Midwifery Stud. 4(4), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.17795/nmsjournal31157 (2015).

McClurkin, S. L. & Smith, C. D. The duration of self-selected music needed to reduce preoperative anxiety. J. PeriAnesthesia Nurs. 3, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jopan.2014.05.017 (2016).

Ng, M. Y. et al. Randomized controlled trial of relaxation music to reduce heart rate in patients undergoing cardiac CT. Eur. Radiol. 26(10), 3635–3642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-016-4215-8 (2016).

Tam, W. W. S., Lo, K. K. H. & Hui, D. S. C. The effect of music during bronchoscopy: A meta-analysis. Hear Lung J. Acute Crit. Care. 45(2), 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2015.12.004 (2016).

Golino, A. J. et al. Impact of an active music therapy intervention on intensive care patients. Am. J. Crit. Care. 28(1), 48–55. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2019792 (2019).

Bradt, J., Dileo, C. & Potvin, N. Music for stress and anxiety reduction in coronary heart disease patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 12(12), CD006577. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006577.pub3 (2013).

Liang, Z. Music intervention during daily weaning trials-A 6-day prospective randomized crossover trial. Complement Ther. Med. 29, 72–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2016.09.003 (2016).

Maeyama, A., Kodaka, M. & Miyao, H. Effect of the music-therapy under spinal anesthesia. Masui 58(6), 684–691 (2009).

Gramaglia, C. et al. Outcomes of music therapy interventions in cancer patients: A review of the literature. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 138, 241–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.04.004 (2019).

Sin, W. M. & Chow, K. M. Effect of music therapy on postoperative pain management in gynecological patients: A literature review. Pain Manag. Nurs. 16(6), 978–987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2015.06.008 (2015).

Chlan, L. & Halm, M. A. Does music ease pain and anxiety in the critically ill?. Am. J. Crit. Care. 22(6), 528–532. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2013998 (2013).

Sanjuán, M., Via, G., Vázquez, B., Moreno, A. M. & Martínez, G. Effect of music on anxiety and pain in patients with mechanical ventilation. Enferm Intensiva. 24(2), 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfi.2012.11.003 (2013) (Spanish).

Gélinas, C., Tousignant-Laflamme, Y., Tanguay, A. & Bourgault, P. Exploring the validity of the bispectral index, the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool and vital signs for the detection of pain in sedated and mechanically ventilated critically ill adults: a pilot study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 27(1), 46–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2010.11.002 (2011).

Ayoub, C. M., Rizk, L. B., Yaacoub, C. I., Gaal, D. & Kain, Z. N. Music and ambient operating room noise in patients undergoing spinal anesthesia. Anesth. Analg. 100(5), 1316–1319. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ANE.0000153014.46893.9B (2005).

Newman, A., Boyd, C., Meyers, D. & Bonanno, L. Implementation of music as an anesthetic adjunct during monitored anesthesia care. J. Perianesthesia Nurs. 25(6), 387–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jopan.2010.10.003 (2010).

Consejería de Sanidad de Castilla-La Mancha. Plan de Salud de Castilla-La Mancha, Horizonte 2025. Capítulo sobre la humanización de la asistencia sanitaria. [internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 23]. Avalaible from https://sanidad.castillalamancha.es/files/documentos/pdf/20230314/plan_de_humanizacion_asistencia_sanitaria_horizonte_25_clm_def_interactivo_v4.pptx_.pdf

Acknowledgements

Dr. SEGURA-HERAS acknowledges the financial support from the Generalitat Valenciana under project PROMETEO/2021/063. To the professionals of the Mobile Emergency Unit of Motilla del Palancar (Cuenca) of the Management of Emergencies and Health Transport in Castilla-La Mancha (SESCAM); without their support the field phase of this study could not have been carried out.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MAGS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing- Original draft, Visualization. JCMC: Validation, Writing- Review and Editing, Supervision. JVSH: Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Writing-Review and Editing, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gregorio-Sanz, M.Á., Marzo-Campos, J.C. & Segura-Heras, J.V. Effects of nursing music intervention on cardiovascular patients transferred in advanced life support ambulances. Sci Rep 15, 7919 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92748-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92748-5