Abstract

Preterm birth (PTB), defined as delivery before 37 weeks, affects 15 million infants annually, accounting for 11% of live births and over 35% of neonatal deaths. While advanced maternal age (≥ 35 years) is a known risk factor, PTB risk in women under 35 is underexplored. This study aimed to develop a machine learning-based model for PTB prediction in women under 35. A retrospective cohort of 2606 cases (2019–2022) equally split between full-term and preterm births was analyzed. Logistic Regression, LightGBM, Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT), and XGBoost models were evaluated. External validation was conducted using 803 independent cases (2023). Model performance was assessed using area under the curve (AUC), accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity. SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values were used to interpret model predictions. The XGBoost model demonstrated superior performance with an AUC of 0.893 (95% CI: 0.860–0.925) on the validation set. In comparison, Logistic Regression, LightGBM, and GBDT achieved AUCs of 0.872, 0.840, and 0.879, respectively. External validation of the XGBoost model yielded an AUC of 0.91 (95% CI: 0.889–0.931). SHAP analysis highlighted seven key predictors: alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), hemoglobin (HGB), urea (UREA), lymphocyte count (Lym1), sodium (Na), and red cell distribution width coefficient of variation (RDWCV). The XGBoost model provides accurate PTB risk prediction and key insights for early intervention in women under 35, supporting its potential clinical utility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Preterm birth (PTB), defined as childbirth before 37 weeks of gestation, affects approximately 15 million infants globally each year, representing 11% of all births1,2. PTB is responsible for over 35% of neonatal deaths3, and nearly half of surviving preterm infants face long-term health challenges such as cerebral palsy, sensory impairments, chronic lung disease, and developmental delays. These complications impose a significant burden on families and healthcare systems4. In China, the PTB rate is around 7.8%, with over 1 million preterm infants born annually5. These infants often experience persistent health issues in respiratory, neurological, and gastrointestinal systems, severely impacting their quality of life6 .

Although advanced maternal age (≥ 35 years) is widely recognized as a key risk factor for PTB, the risk among women under 35 should not be underestimated. Physiological and socio-economic factors, such as teenage pregnancy, malnutrition, and lower socioeconomic status, can increase PTB risk in younger women7. Additionally, younger women may have limited access to or awareness of prenatal care, which can exacerbate pregnancy complications8. Additionally, younger women may have limited access to or awareness of prenatal care, which can exacerbate pregnancy complications.

Accurately predicting and intervening in PTB risk is crucial for improving neonatal health outcomes. Traditional methods of PTB prediction often fail to accurately identify high-risk populations. Recently, machine learning techniques have shown promise in overcoming these limitations by integrating diverse biomarkers and clinical data, thereby enhancing prediction accuracy9. These models facilitate early intervention, which can help reduce PTB incidence and its associated complications.

This study aims to develop a machine learning-based predictive model for PTB risk in women under 35, utilizing a comprehensive baseline analysis of clinical and biomarker data. By identifying key risk factors, this study seeks to improve PTB risk prediction accuracy and create a clinically applicable tool for risk assessment. This approach not only has the potential to reduce PTB incidence but also aims to enhance both neonatal and maternal health outcomes, thereby contributing to better overall maternal-infant health.

Methods

Data sources and sample selection

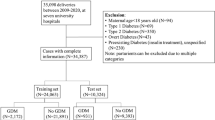

This retrospective study utilized electronic health record (EHR) data from Hangzhou First People’s Hospital, Zhejiang Province, China, including pregnant women under 35 years old who received prenatal care or delivered between January 2019 and December 2022. Women under 35 were considered low-risk for preterm birth, based on guidelines from the World Health Organization (WHO)10and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)11, which define 35 years as the threshold for advanced maternal age, associated with increased pregnancy risks. A total of 2866 cases were initially included. To balance the preterm birth (PTB) and full-term birth (FTB) groups, a structured sampling approach was applied, resulting in 2606 cases (1303 PTB and 1303 FTB, Fig. 1). Clinical and laboratory data, including demographic information (age, BMI), liver and kidney function indices, complete blood count, and thyroid function, were collected during prenatal visits at 22–24 weeks of gestation. To mitigate potential selection bias introduced by structured sampling and assess the model’s generalizability, an external validation dataset (803 cases: 492 FTB, 311 PTB) collected from January 2023 to December 2023 provided a temporally distinct cohort for model validation.

Laboratory testing procedures

Basic clinical information, including age, BMI, and medical history, was collected at prenatal visits. Blood samples from all participants were obtained at 22–24 weeks of gestation and analyzed in the same hospital laboratory. Liver and kidney function markers (ALT, AST, ALP, UREA, creatinine, etc.) were measured using the Beckman Coulter AU680 analyzer. Serum AFP was assessed with the Abbott i2000 chemiluminescence analyzer. Thyroid function (TSH, FT3, FT4, etc.) and sex hormones (E2, P, T, etc.) were analyzed using the Siemens Atellica system. CBC parameters were measured with the Mindray BC-7500 hematology analyzer, while coagulation markers were assessed using the Sysmex CS-5000 system. All tests followed standardized protocols and manufacturer guidelines to ensure accuracy and reliability.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were single pregnancies with maternity records established at 22–24 weeks, at least two prenatal examinations, and complete clinical and laboratory data. Deliveries between 24 and 36 weeks were classified as PTB, while deliveries at 37 weeks or later were classified as FTB. Exclusion criteria included severe comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, diabetes), multiple pregnancies, incomplete data, and cases of miscarriage or stillbirth.

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee (Approval Number: ZN-20240613-019-01) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Data confidentiality and privacy protection policies were strictly followed.

Feature selection

Key predictors of PTB were identified through a dual-step approach. First, baseline comparisons between the FTB and PTB groups were performed using Levene’s test, followed by t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests based on data distribution. Significant variables were then analyzed using Lasso regression with L1 regularization to refine the selection of features most predictive of PTB. This systematic process ensured robust predictor identification for model development.

Machine learning model development

Multiple machine learning algorithms, including Logistic Regression, LightGBM, GBDT, and XGBoost, were evaluated for PTB prediction. The dataset was split into a training set (70%) and a validation set (30%). Feature engineering steps included standardization, normalization, and imputation of missing data to ensure data quality. Model performance was assessed using metrics such as AUC, PR-AUC, F1 score, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity, with emphasis on PR-AUC and F1 score to address data imbalance.

A 5-fold cross-validation strategy was employed to optimize hyperparameters and improve generalization. XGBoost demonstrated superior performance in handling nonlinear relationships and feature interactions and was selected as the final model. The optimized XGBoost model was retrained on the entire training set to enhance predictive accuracy and robustness.

Model evaluation

The XGBoost model was evaluated on both independent and external validation sets using AUC, PR-AUC, F1 score, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity. AUC measured overall discrimination ability, while PR-AUC highlighted performance in identifying PTB cases in imbalanced datasets. Sensitivity and specificity quantified the model’s ability to correctly classify PTB and FTB cases, and F1 score provided a balanced assessment of sensitivity and precision.

Model interpretation and clinical application

To enhance interpretability, SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values were used to quantify the contribution of individual features to PTB predictions. This provided a transparent understanding of how factors like age, BMI, and biochemical markers influence model output, offering actionable clinical insights.

An online prediction tool was developed to facilitate the clinical application of the XGBoost model. This user-friendly interface enables healthcare professionals to input patient data and receive real-time PTB risk assessments, supporting timely and informed prenatal care decisions. The tool integrates seamlessly into clinical workflows, advancing precision medicine in maternal health.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software on Windows and the Deepwise and Beckman Coulter DxAI platform (https://www.xsmartanalysis.com/beckman/login/). Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR), and categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Independent samples t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests were applied for continuous variables, while Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests were used for categorical variables. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Population characteristics

A total of 2606 pregnant women under the age of 35 were included in this study, with 1303 cases in each of the PTB and FTB groups. Baseline analysis revealed significant differences in various clinical and laboratory parameters between the two groups. A total of 32 variables, including demographic information, liver and kidney function indices, blood glucose and lipids, cardiac enzymes, biochemical markers, and thyroid function indices, were analyzed.

Notably, several variables showed statistically significant differences between the PTB and FTB groups (p < 0.05). For instance, the median age in the PTB group was 29 years (IQR 27–32 years), compared to 29 years (IQR 27–31 years) in the FTB group, with a significant difference (p < 0.001). Similarly, the median BMI was 25.391 in the PTB group, while in the FTB group, it was 25.649 (p = 0.013). Significant differences were also observed in liver function indices, such as ALT and ALB, kidney function markers like UREA and CREA, and blood lipids, particularly TCHO (p < 0.001).

The PTB group exhibited higher ALT and ALB levels, suggesting potential liver dysfunction, while elevated UREA and CREA levels indicated renal stress. Additionally, increased TCHO levels in the PTB group may reflect altered lipid metabolism, which could contribute to PTB risk. These findings suggest that the identified clinical and laboratory markers could be associated with an increased risk of PTB, as detailed in Table 1.

Identification of key predictors for PTB risk

Lasso regression was applied for feature selection due to its ability to reduce model complexity and prevent overfitting through L1 regularization. A key advantage of Lasso regression is its capacity to automatically identify the most influential predictors, thereby improving model interpretability and stability. In this study, Lasso regression was used to identify significant predictors of PTB, with an optimal λ value of 0.014.

The selected variables included age, GLB, ALT, ALP, ALB, IBIL, UREA, CREA, TCHO, Na, DBHB, FT3, TSH, AFP, FIB, AISI, WBC, absolute neutrophil count (Neu1), absolute lymphocyte count (Lym1), absolute eosinophil count (Eos1), HGB, MCHC, RDWCV, and PLT. The coefficients resulting from the Lasso regression are shown in Fig. 2A, and the cross-validation curve is presented in Fig. 2B.

LASSO Regression Analysis. (A) Coefficient Profiles. This plot displays the LASSO regression coefficient profiles for different values of the regularization parameter (Log Lambda). Each colored line represents the trajectory of a coefficient for a specific feature as the regularization strength increases. (B) Binomial Deviance. This plot shows the binomial deviance of the LASSO regression model as a function of the regularization parameter (Log Lambda). The vertical dashed lines indicate the values of lambda that minimize the binomial deviance (left) and the one-standard-error rule (right). The red dots represent the binomial deviance for each lambda value, with error bars indicating the standard error.

Following feature selection, these predictors were used in subsequent analyses to assess their impact on PTB risk. The selected features were incorporated into various machine learning models, improving the accuracy of PTB risk prediction.

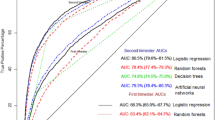

Performance comparison of machine learning models

Various machine learning models—Logistic Regression, LightGBM, GBDT, and XGBoost—were evaluated for predicting preterm birth (PTB) risk. Model performance was assessed on the validation set using multiple metrics, including AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, F1 score, and Kappa value. Among these, XGBoost demonstrated the best overall performance, achieving an AUC of 0.911 (95% CI: 0.887–0.935), alongside strong predictive metrics summarized in Table 2. These results highlight XGBoost’s superior ability to discriminate between PTB and full-term birth (FTB) cases.

In comparison, the other models showed slightly inferior performance on the validation set. Logistic Regression achieved an AUC of 0.872 (95% CI: 0.842–0.902), LightGBM had an AUC of 0.840 (95% CI: 0.806–0.873), and GBDT achieved an AUC of 0.879 (95% CI: 0.849–0.908). Despite reasonable performance across these models, none surpassed XGBoost in terms of overall predictive power.

To further validate the XGBoost model, ROC curves were analyzed. The ROC curve for both training and validation datasets confirmed excellent discriminative ability (Fig. 3), with consistent AUC values indicating the model’s robustness. These findings collectively validate the XGBoost model as a reliable and accurate approach for PTB risk prediction, demonstrating its potential for clinical application in identifying high-risk pregnancies.

Predictive model development and validationn

The XGBoost algorithm was applied to predict preterm birth (PTB) risk using a dataset of 2606 samples. A test set comprising 781 samples (30%) was randomly selected, with the remaining data used for 5-fold cross-validation during model training. Feature importance analysis and evidence-based selection identified seven significant predictors: ALP, AFP, HGB, UREA, Lym1, Na, and RDWCV.

The XGBoost model exhibited robust predictive performance, achieving an AUC of 0.950 (95% CI: 0.940–0.960) on the training set, 0.893 (95% CI: 0.860–0.925) on the validation set, and 0.890 (95% CI: 0.868–0.913) on the test set. The similarity of AUC values across datasets confirmed that the model was well-fitted and did not exhibit overfitting. Additionally, the learning curve indicated stable performance as training sample size increased, reflecting strong generalization capability (Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 4A-C).

ROC Curves for XGBoost Model Performance. (A)Training Set ROC Curve: The ROC curve for the XGBoost model on the training set, with an AUC of 0.950 (95% CI: 0.940-0.960).

(B) Validation Set ROC Curve: The ROC curve for the XGBoost model on the validation set, with an AUC of 0.893 (95% CI: 0.860-0.925). (C)Test Set ROC Curve: The ROC curve for the XGBoost model on the test set, with an AUC of 0.890 (95% CI: 0.868-0.913).

For external validation, the model was tested on an independent dataset collected during a different time period. The XGBoost model achieved an AUC of 0.91 (95% CI: 0.889–0.931), slightly exceeding its performance on the internal test set. The consistent results across internal and external datasets demonstrated the model’s robustness and applicability to different populations and temporal contexts (Supplementary Table 2, Fig. 5A-C).

External Validation of XGBoost Model. (A) ROC curve for the external validation set: The ROC curve for the XGBoost model on the external validation set, with an AUC of 0.91 (95% CI: 0.889-0.931). (B) Test Set Decision Curve: The calibration curve showing consistency between predicted probabilities and actual incidence for the external validation set. (C) Calibration plots for the external validation set: The calibration curve showing consistency between predicted probabilities and actual incidence for the external validation set.

Explaining model insights and practical use

SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values were used to interpret the XGBoost model’s predictions, highlighting the contributions of seven key predictors: ALP, AFP, HGB, UREA, Lym1, Na, and RDWCV. Figure 6A visualizes the SHAP value distribution for these predictors, where red dots indicate high feature values and blue dots indicate low values. Figure 6B ranks the predictors by mean SHAP values, with ALP and AFP showing the strongest positive associations with PTB risk, while HGB and UREA exhibited protective effects.

SHAP Analysis of Feature Importance. (A) SHAP Value Distribution: This plot illustrates the SHAP values for individual predictions of the XGBoost model, showcasing the impact of each feature on the output. Each dot represents a SHAP value for a feature in a specific prediction. Red dots indicate high feature values, while blue dots represent low feature values. (B) Mean SHAP Values: This bar chart displays the average SHAP values for each feature, highlighting their overall contribution to the model’s predictions. Higher mean SHAP values indicate greater importance in predicting PTB risk.

This analysis provides actionable insights into how feature variations influence PTB risk. For instance, higher UREA values were linked to reduced risk, as reflected by negative SHAP values. These findings enhance the model’s interpretability, offering clinicians a clear understanding of predictor impact.

To facilitate clinical use, an online prediction tool was developed. By integrating the XGBoost model, the tool enables healthcare professionals to input patient data for real-time PTB risk assessments. Its user-friendly interface supports rapid evaluations, aiding personalized prenatal care. The tool is accessible at: http://www.xsmartanalysis.com/model/list/predict/model/html?mid=15123&symbol=5sW17aM15742Df8pY994.

Discussion

This study applied various machine learning models, particularly the XGBoost model, to predict the risk of PTB. The XGBoost model demonstrated superior performance, achieving AUCs of 0.950, 0.893, and 0.890 on the training, validation, and test sets, respectively. SHAP value analysis confirmed the importance of seven variables: ALP, AFP, HGB, UREA, Lym1, Na, and RDWCV. These predictors provide actionable insights for clinicians, enabling early identification of high-risk pregnancies and guiding timely interventions to reduce PTB incidence.

Compared to traditional statistical methods, the XGBoost model outperformed Logistic Regression in predictive accuracy. Previous studies using Logistic Regression models typically report AUCs ranging from 0.75 to 0.85. In contrast, the XGBoost model achieved an AUC of 0.893 on the validation set, representing a significant improvement12,13,14. This enhancement reflects XGBoost’s ability to model complex, nonlinear relationships and interactions between variables more effectively than traditional approaches15. Additionally, external validation showed that the XGBoost model achieved an AUC of 0.91 on an independent dataset, further validating the model’s robustness and generalization capability. Although the AUC for the external dataset was slightly lower than that for the internal validation set, the overall performance remained excellent, indicating the model’s applicability across different time periods and populations.

The identification of biomarkers such as ALP, AFP, and UREA aligns with findings from previous studies, emphasizing their importance in PTB risk assessment. Elevated AFP levels have been linked to increased PTB risk, as corroborated by our results, where AFP ranked second in predictive importance16. This association likely stems from AFP’s role in placental function and fetal development17. Similarly, elevated ALP levels, which may be associated with placental dysfunction, infection, sepsis, and underlying inflammatory and oxidative stress mechanisms, emerged as a critical predictor of PTB risk, reinforcing prior research findings18,19,20.

This study also provides novel insights by identifying unique associations. For example, the significant relationship between lymphocyte count (Lym1) and PTB risk diverges from some previous studies that found no notable association with lymphocyte markers21. This suggests a potential role of maternal immune status in PTB pathophysiology, warranting further investigation.

Interestingly, the inverse relationship observed between UREA levels and PTB risk offers a new perspective. Lower urea levels may indicate better maternal metabolic and nutritional status, contributing to a stable intrauterine environment that reduces PTB risk. This contrasts with earlier findings22,23, highlighting the need for additional research to explore this physiological mechanism24.

The significance of RDWCV in PTB prediction was also consistent with existing research. High RDWCV levels have been associated with inflammation and oxidative stress, which are important risk factors for PTB25,26. Our study confirmed these findings using a machine learning model, indicating that RDWCV can serve as a reliable predictor of PTB risk25,26,27,28. Elevated RDWCV may reflect chronic inflammation and oxidative stress in the body, key factors in PTB risk29,30.

Similarly, abnormal sodium (Na) levels were identified as significant predictors, corroborating earlier studies linking electrolyte imbalances to adverse pregnancy outcomes. These imbalances may signal underlying conditions such as fluid dysregulation, which could contribute to PTB risk31,32.

This study’s key contribution lies in leveraging advanced machine learning techniques for PTB prediction while ensuring model interpretability through SHAP analysis. By quantifying the influence of individual predictors, SHAP enhances the model’s clinical utility, offering clinicians a transparent and reliable decision-support tool. Furthermore, the development of an online prediction tool integrates these insights into a user-friendly platform, facilitating real-time risk assessment and personalized prenatal care.

In conclusion, this research demonstrates the value of machine learning models like XGBoost in improving PTB risk prediction. The integration of SHAP analysis provides actionable insights, enhancing clinical decision-making. These findings underscore the importance of leveraging advanced analytical methods to identify high-risk pregnancies early, ultimately contributing to improved maternal and neonatal health outcomes.

Limitations and future directions

This study has several limitations. First, as a single-center retrospective analysis from Hangzhou First People’s Hospital, the findings may lack generalizability to other regions or populations. Although external validation was conducted to assess generalizability, the structured sampling approach may introduce selection bias. Additionally, the relatively small sample size may limit the model’s predictive robustness, especially when applied to broader or more diverse populations. Second, important factors such as genetic and environmental influences were not included, which may affect the model’s predictive accuracy. Finally, while the model showed high AUC values, its practicality and cost-effectiveness in clinical use require further evaluation.

Future research should expand the sample size and include multicenter data to improve generalizability. Incorporating additional variables, such as genetic and environmental factors, could enhance predictive accuracy. Validating the model in clinical applications and assessing its real-world effectiveness and cost-efficiency are essential next steps. Applying the model in early pregnancy may enable earlier identification of high-risk individuals, facilitating timely interventions to reduce PTB risk.

Conclusion

This study effectively predicted the risk of PTB in women under 35 years old using various machine learning models, particularly the XGBoost model. The integration of SHAP value analysis provides clear insights into the role of individual variables, enhancing the model’s interpretability and clinical utility. By leveraging advanced analytical methods, this research improves the early identification and management of high-risk pregnancies, ultimately contributing to better maternal and neonatal health outcomes. Further validation and refinement of our model will be essential for its integration into routine clinical practice, paving the way for more effective and personalized maternal-infant healthcare.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- FTB:

-

Full-Term Birth

- PTB:

-

Preterm Birth

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- DBP:

-

Diastolic Blood Pressure

- SBP:

-

Systolic Blood Pressure

- AG:

-

Anion Gap

- GLB:

-

Globulin

- GLU:

-

Glucose

- ALT:

-

Alanine Aminotransferase

- AST:

-

Aspartate Aminotransferase

- GT:

-

Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase

- ALP:

-

Alkaline Phosphatase

- ALB:

-

Albumin

- TBIL:

-

Total Bilirubin

- IBIL:

-

Indirect Bilirubin

- DBIL:

-

Direct Bilirubin

- UREA:

-

Urea

- CREA:

-

Creatinine

- UA:

-

Uric Acid

- MG:

-

Magnesium

- TCHO:

-

Total Cholesterol

- LPa:

-

Lipoprotein(a)

- CK:

-

Creatine Kinase

- CKMB:

-

Creatine Kinase-MB

- LDH:

-

Lactate Dehydrogenase

- AMY:

-

Amylase

- ASO:

-

Antistreptolysin O

- RF:

-

Rheumatoid Factor

- Na:

-

Sodium

- DBHB:

-

D-β-Hydroxybutyrate

- CRP:

-

C-Reactive Protein

- TBA:

-

Total Bile Acid

- CG:

-

Cholinesterase

- TT4:

-

Total Thyroxine

- FT3:

-

Free Triiodothyronine

- FT4:

-

Free Thyroxine

- TSH:

-

Thyroid Stimulating Hormone

- AFP:

-

Alpha-Fetoprotein

- TT:

-

Total Testosterone

- FIB:

-

Fibrinogen

- AISI:

-

Aggregate Index of Systemic Inflammation

- NLPR:

-

Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio

- SII:

-

Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index

- SIRI:

-

Systemic Inflammation Response Index

- NLR:

-

Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio

- PLR:

-

Platelet-Lymphocyte Ratio

- LMR:

-

Lymphocyte-Monocyte Ratio

- Dnlr:

-

Double Negative Lymphocyte Ratio

- WBC:

-

White Blood Cell

- Neu:

-

Neutrophil Percentage

- Lym:

-

Lymphocyte Percentage

- Mon:

-

Monocyte Percentage

- Eos:

-

Eosinophil Percentage

- Bas:

-

Basophil Percentage

- Neu1:

-

Neutrophil Absolute Value

- Lym1:

-

Lymphocyte Absolute Value

- Mon1:

-

Monocyte Absolute Value

- Eos1:

-

Eosinophil Absolute Value

- Bas1:

-

Basophil Absolute Value

- HGB:

-

Hemoglobin

- MCV:

-

Mean Corpuscular Volume

- MCHC:

-

Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration

- RDWCV:

-

Red Cell Distribution Width-Coefficient of Variation

- PLT:

-

Platelet Count

- PCT:

-

Procalcitonin

- PDW:

-

Platelet Distribution Width

- SHAP:

-

SHapley Additive exPlanations

- AUC:

-

Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio CI: Confidence Interval

- PPV:

-

Positive Predictive Value

- NPV:

-

Negative Predictive Value

- Acc:

-

Accuracy

- Sens:

-

Sensitivity

- Spec:

-

Specificity

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- ACOG:

-

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

References

Ville, Y. & Rozenberg, P. Predictors of preterm birth. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 52, 23–32 (2018).

Ohuma, E. O. et al. National, regional, and global estimates of preterm birth in 2020, with trends from 2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet 402(10409), 1261–1271 (2023).

Kleinhout, M. Y. et al. Evidence-based interventions to reduce mortality among preterm and low-birthweight neonates in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob Health 6(2). (2021).

Frey, H. A. & Klebanoff, M. A. The epidemiology, etiology, and costs of preterm birth. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 21(2), 68–73 (2016).

Cao, G., Liu, J. & Liu, M. Global, regional, and National incidence and mortality of neonatal preterm birth, 1990–2019. JAMA Pediatr. 176(8), 787–796 (2022).

Luu, T. M., Rehman Mian, M. O. & Nuyt, A. M. Long-Term impact of preterm birth: neurodevelopmental and physical health outcomes. Clin. Perinatol. 44(2), 305–314 (2017).

Afulani, P. A., Altman, M., Musana, J. & Sudhinaraset, M. Conceptualizing pathways linking women’s empowerment and prematurity in developing countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 17(Suppl 2), 338 (2017).

Perak, A. M. et al. Associations of maternal cardiovascular health in pregnancy with offspring cardiovascular health in early adolescence. JAMA 325(7), 658–668 (2021).

Yang, Q. et al. Reporting and risk of bias of prediction models based on machine learning methods in preterm birth: A systematic review. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 102(1), 7–14 (2023).

Tuncalp, Ӧ. et al. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience-going beyond survival. BJOG 124(6), 860–862 (2017).

American College of O, Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric Practice SfM-FM. Medically indicated Late-Preterm and Early-Term deliveries: ACOG committee opinion, number 831. Obstet. Gynecol. 138(1), e35–e39 (2021).

Feleke, S. F., Anteneh, Z. A., Wassie, G. T., Yalew, A. K. & Dessie, A. M. Developing and validating a risk prediction model for preterm birth at Felege Hiwot comprehensive specialized hospital, North-West Ethiopia: a retrospective follow-up study. BMJ Open. 12(9), e061061 (2022).

Arabi Belaghi, R., Beyene, J. & McDonald, S. D. Prediction of preterm birth in nulliparous women using logistic regression and machine learning. PLoS One. 16(6), e0252025 (2021).

Mboya, I. B., Mahande, M. J., Obure, J. & Mwambi, H. G. Predictors of Singleton preterm birth using multinomial regression models accounting for missing data: A birth registry-based cohort study in Northern Tanzania. PLoS One. 16(4), e0249411 (2021).

Stahlschmidt, S. R., Ulfenborg, B. & Synnergren, J. Multimodal deep learning for biomedical data fusion: a review. Brief. Bioinform 23(2). (2022).

Hu, J. et al. First-trimester maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein is not a good predictor for adverse pregnancy outcomes: A retrospective study of 3325 cases. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 20(1), 104 (2020).

Melamed, N. et al. Maternal First-Trimester Alpha-Fetoprotein and Placenta-Mediated pregnancy complications. Hypertension 80(11), 2415–2424 (2023).

Yuan, W., Chen, L. & Bernal, A. L. Is elevated maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein in the second trimester of pregnancy associated with increased preterm birth risk? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 145(1), 57–64 (2009).

Jyothi, L. et al. Prediction of preterm delivery among Low-risk Indian pregnant women: discriminatory power of cervical length, serum ferritin, and serum Alpha-fetoprotein. Int. J. Appl. Basic. Med. Res. 13(4), 198–203 (2023).

Glowska-Ciemny, J. et al. Fetal and placental causes of elevated serum Alpha-Fetoprotein levels in pregnant women. J. Clin. Med. 13(2). (2024).

Peng, L. et al. Relationship between Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio with Spontaneous Preterm Birth: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Immunol Res 2023:6841344. (2023).

Xu, Z. et al. Elevated levels of renal function tests conferred increased risks of developing various pregnancy complications and adverse perinatal outcomes: insights from a population-based cohort study. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 61(10), 1760–1769 (2023).

Lu, W., Hu, M. J., Zhu, D. D., Lin, F. J. & Huang, H. D. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of pregnancy-related acute kidney injury: a case series study. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 55(9), 2249–2255 (2023).

Cheung, K. L. & Lafayette, R. A. Renal physiology of pregnancy. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 20(3), 209–214 (2013).

Go, H. et al. Red cell distribution width as a predictor for bronchopulmonary dysplasia in premature infants. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 7221 (2021).

Tolunay, H. E. & Elci, E. Importance of haemogram parameters for prediction of the time of birth in women diagnosed with threatened preterm labour. J. Int. Med. Res. 48(4), 300060520918432 (2020).

Perrone, S. et al. Placental histological examination and the relationship with oxidative stress in preterm infants. Placenta 46, 72–78 (2016).

Kai, Y. et al. Red blood cell distribution width-standard deviation but not red blood cell distribution width-coefficient of variation as a potential index for the diagnosis of iron-deficiency anemia in mid-pregnancy women. Open. Life Sci. 16(1), 1213–1218 (2021).

Crook, J. M., Horgas, A. L., Yoon, S. L., Grundmann, O. & Johnson-Mallard, V. Vitamin C plasma levels associated with inflammatory biomarkers, CRP and RDW: results from the NHANES 2003–2006 surveys. Nutrients 14(6). (2022).

Joosse, H. J. et al. In-vitro and in-silico evidence for oxidative stress as drivers for RDW. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 9223 (2023).

Ajong, A. B. et al. Association of hypertension in pregnancy with serum electrolyte disorders in late pregnancy among Cameroonian women. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 20940 (2023).

Belzile, M., Pouliot, A., Cumyn, A. & Cote, A. M. Renal physiology and fluid and electrolyte disorders in pregnancy. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 57, 1–14 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to all the individuals and institutions who have contributed to this research. We especially thank our colleagues for their invaluable support and collaboration. We are also grateful to the Beckman Coulter Technology and Innovation Platform for their technical support, which was instrumental in the analysis and successful completion of this study.

Funding

This work was supported by Zhejiang Medicine and Health Scientific Research Project (2022RC226).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XJ. Teng conceptualized the study, developed the methodology, curated and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. MT. Liu contributed to investigation, validation, manuscript review, and managed project administration, being recognized as co-first author for equal contribution. ZY. Wang and XY. Dong supervised the study, provided resources, reviewed the manuscript, and served as corresponding authors. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hangzhou First People’s Hospital (Approval Number: ZN-20240613-019-01). The research was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent before inclusion in the study. Participants were assured of the confidentiality of their personal information and their right to withdraw from the study at any time without any consequence. The study strictly adhered to ethical standards and privacy protection policies to ensure data confidentiality and the protection of participants’ privacy rights.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Teng, X., Liu, M., Wang, Z. et al. Machine learning prediction of preterm birth in women under 35 using routine biomarkers in a retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 10213 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92814-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92814-y