Abstract

There is increasing recognition of the role of oxidative balance in testosterone deficiency (TD). This study investigates the association between the oxidative balance score (OBS) and TD prevalence among adult males in the United States. Data were obtained from a cross-sectional study of 3276 adult men in the 2011–2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. OBS was assessed based on 16 nutrient and 4 lifestyle components. Multivariate logistic regression and subgroup analyses were conducted to calculate the odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association between OBS and TD prevalence. After adjusting for potential confounders, a negative linear association was observed between OBS and TD prevalence (OR = 0.98, 95% CI 0.97–1.00). Participants in the highest OBS tertile had lower odds of TD compared to those in the lowest tertile (OR = 0.92, 95% CI 0.69–1.21). Lifestyle components of OBS were significantly associated with lower TD prevalence (OR = 0.85, 95% CI 0.81–0.90). Furthermore, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator regression identified key OBS components most strongly associated with TD, with physical activity exerting the greatest influence. A predictive nomogram model incorporating these components demonstrated a discriminatory power with an area under the curve of 0.744 (95% CI 72.4–76.4%). In conclusion, this study demonstrates an inverse association between OBS and TD prevalence, suggesting a potential role of oxidative balance in testosterone regulation among US males.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Testosterone, a key male sex hormone primarily produced by the testes and adrenal glands, plays an essential role in regulating various physiological functions, including reproductive health, spermatogenesis, muscle mass maintenance, and cellular protein and lipid metabolism1,2. Testosterone deficiency (TD), also known as male hypogonadism, is an endocrine disorder characterized by inadequate serum testosterone levels, which can result in symptoms such as low energy, depression, reduced libido, and erectile dysfunction1,3. TD affects approximately 20% of men, with its prevalence increasing significantly with age—up to 50% of men over 80 are classified as having TD4. Moreover, data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) have highlighted a concerning decline in testosterone levels among adult men in recent decades5. This decline parallels a global decrease in fertility rates6, with male factors, including TD, contributing to over 40–50% of infertility cases7,8. Given these trends, elucidating factors driving TD is critical for addressing this growing public health concern.

Recent evidence underscores a strong association between oxidative stress and TD9. Epidemiological studies have consistently identified oxidative stress in males with TD10,11. Oxidative stress occurs when reactive oxygen species (ROS) exceed antioxidant defenses, damaging Leydig cells—the testosterone-producing cells in the testes—and disrupting the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis, ultimately reducing testosterone production2,12,13.Numerous studies have implicated factors such as reduced intake of dietary antioxidants (e.g., folic acid, calcium, vitamin C, and vitamin E) and pro-oxidant lifestyle behaviors (e.g., smoking and alcohol consumption) in the onset of oxidative stress and TD14,15. Mitigating oxidative stress through lifestyle modifications or antioxidant supplementation has been proposed as a potential strategy for managing or preventing TD15,16. Collectively, these findings highlight the central role of oxidative stress in TD and emphasize the importance of dietary and lifestyle choices in disease prevention.

The oxidative balance score (OBS) is a composite metric that integrates 20 dietary and lifestyle factors, reflecting the overall balance between pro-oxidants and antioxidants across various exposures17. The total OBS is calculated by summing the weighted tertile scores of antioxidant and pro-oxidant components, with higher scores indicating a predominance of antioxidants over pro-oxidants. Although OBS has been validated in numerous studies across a range of diseases17,18, limited research has explored its specific association with TD.

To address this gap, we aimed to investigate the relationship between OBS—encompassing both dietary and lifestyle factors—and the prevalence of TD using a large, nationally representative sample from the NHANES database spanning 2011 to 2016. By identifying key antioxidant and pro-oxidant exposures associated with TD prevalence, this study provides insights into the potential role of oxidative balance in male endocrine health and its relevance for dietary and lifestyle interventions aimed at TD management.

Methods

Study population

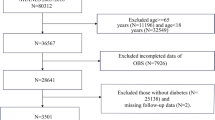

This study utilized data from the NHANES database (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm), developed by the National Center for Health Statistics in the United States. NHANES is a nationally representative, cross-sectional survey that provides key health statistics through stratified, multi-stage probability sampling, encompassing data from interviews, physical examinations, and laboratory tests. For this analysis, we included data from three consecutive NHANES cycles (2011–2012, 2013–2014, and 2015–2016). Of the 29,902 participants initially recruited, we excluded individuals younger than 20 years, female participants, those with missing OBS component data, and individuals without testosterone measurements. Furthermore, to align with standard clinical guidelines for assessing testosterone levels, we excluded participants whose serum samples were not collected in the morning after an overnight fast19. After applying these criteria, the final analytic sample consisted of 3276 eligible participants, as illustrated in Fig. 1. All NHANES studies adhered to the ethical guidelines established by the National Center for Health Statistics’ Ethical Review Committee. Before participation, all individuals received detailed information about the study’s objectives, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant, ensuring voluntary participation and the confidentiality of their personal and health data.

OBS evaluation

The OBS data were collected by NHANES through 24-h dietary recall interviews conducted at the Mobile Examination Center (MEC). The OBS integrates 16 dietary and 4 lifestyle factors to assess the overall balance between pro-oxidants and antioxidants. Antioxidant factors included dietary fiber, carotenoids, riboflavin, niacin, total folate, vitamins B6, B12, C, and E, calcium, magnesium, zinc, copper, and selenium, and metabolic equivalent (MET) levels, based on previous research findings20. MET was used to represent the relative energy expenditure associated with various physical activities, including vigorous and moderate work-related activities, walking or bicycling for transportation, and vigorous or moderate leisure-time physical activities. Pro-oxidant factors included total fat and iron intake, cotinine levels (used as a marker for smoking exposure due to its long half-life and sensitivity to both active and passive smoking), body mass index (BMI), and alcohol consumption12.

The OBS was calculated by summing the weighted tertile scores of antioxidant and pro-oxidant components. Pro-oxidant components were scored as 2, 1, and 0 for the lowest to highest tertile groups, respectively, while antioxidant components were scored inversely as 0, 1, and 2. Thus, a higher OBS indicates a greater predominance of antioxidant exposure. Further details on the OBS scoring methodology are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Testosterone deficiency and assessment of serum testosterone

Based on the guidelines of the American Urological Association (AUA), a condition characterized by TD was defined as a serum testosterone level below 300 ng/dL19. To minimize biological variability, serum specimens were collected in the morning after overnight fasting. After that, the specimens were shipped frozen on dry ice for immediate use or stored at − 70 °C in the long term. To measure total serum testosterone levels, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) developed isotope dilution-liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (ID-LC–MS/MS) for routine analysis, with the lowest linearity limit of 0.75 ng/dL. The methodology details for testosterone determination in the NHANES laboratory can be accessed at: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Data/Nhanes/Public/2013/DataFiles/TST_H.htm.

Covariates

Based on previous literature, we included factors potentially associated with testosterone levels. Data on covariates were collected through questionnaires, physical examinations, and laboratory tests. Age was categorized into three groups: 20–39 years, 40–64 years, and ≥ 65 years. The poverty-to-income ratio (PIR), a proxy for household income, was classified into three categories: ≤ 1.3, 1.31–3.5, and > 3.521,22. Race/ethnicity was grouped as White, Black, Mexican and other races. Education level was categorized as below high school, high school, and above high school. Marital status was divided into married or living with a partner and others. Since individuals receiving antihypertensive or hypoglycemic treatment may have blood pressure or glucose levels within the normal range at the time of measurement, information on hypertension and diabetes was obtained from participants’ self-reported responses in health questionnaires. Given the potential association between dietary habits and TD, we included total energy intake (kcal) as a covariate to partially account for overall dietary intake characteristics23. Furthermore, we also included a covariate for the seasonal timing of serum sample collection (November 1–April 30, May 1–October 31) to account for potential seasonal variations in testosterone levels, as testosterone can fluctuate in response to changes in light exposure and temperature.

Statistical analysis

Mean ± standard deviation (SD) and frequency (proportions) were fully used to describe the baseline characteristics of all participants. Linear regression was used to correlate continuous variables, while the chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. For other continuous variables, Lilliefors tests were first used to test their normality, according to which two-sample t tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were performed to detect group differences. In order to thoroughly investigate the relationship between OBS and TD, three models were developed using multivariate logistic regression analysis. Model 1 included no covariate adjustments. Model 2 was adjusted for age and race, while Model 3 accounted for age, race, PIR, education level, marital status, diabetes, hypertension, total energy intake, and seasonal timing of serum sample collection. Adjusted the odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated, smooth curve fitting was performed to explore the association between the identified confounders and outcome variables. Additionally, due to potential correlations among OBS components, the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) method offers a more stable selection of key predictors compared to traditional stepwise approaches24. Therefore, we developed a predictive nomogram model based on the key OBS factors identified through LASSO regression and assessed its discriminatory power using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Sensitivity analyses were performed in patients without diabetes, without hypertension, and without seasonal timing of serum sample collection. Two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical research uses the statistical computing and graphing software R (version 4.2.1, https://cran.r-project.org/doc/FAQ/R-FAQ.html#Citing-R) and EmpowerStats (version 4.0).

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population

A total of 29,902 participants from NHANES (2011–2016) were initially considered for this study (Fig. 1). Following the application of predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, 15,151 female participants, 4,429 individuals with missing OBS component data, 650 participants without testosterone evaluations, 2,913 individuals under the age of 20, and 3483 participants whose serum samples were not collected during morning hours were excluded (Fig. 1). Ultimately, 3276 participants met the eligibility criteria and were categorized into the non-TD group (total testosterone > 300 ng/dL, n = 2574) and the TD group (total testosterone < 300 ng/dL, n = 702) (Table 1). Compared to the non-TD group, participants in the TD group were older (52.68 ± 17.23 vs. 48.00 ± 17.55 years) and had higher prevalence of hypertension (49.57% vs. 33.26%) and diabetes (29.06% vs. 13.17%) (P < 0.001). Significant difference in marital status was also observed between the groups (P < 0.05) (Table 1). Other characteristics including PIR, race, education level, and seasonal timing of serum sample collection, did not differ significantly between TD and non-TD groups (Table 1).

We further analyzed the OBS and its components between the TD and non-TD groups (Table 2). The TD group demonstrated significantly lower total OBS (P < 0.001), dietary OBS (P < 0.05), and lifestyle OBS scores (P < 0.001) compared to the non-TD group. Among dietary OBS components, riboflavin (P < 0.05), niacin (P < 0.001), vitamin B6 (P < 0.001), and magnesium (P < 0.01) were significantly lower in the TD group, while other dietary components showed no significant differences. For lifestyle OBS components, physical activity (MET) (P < 0.05), BMI (P < 0.001), and cotinine levels (P < 0.01) differed significantly between the groups, though alcohol consumption scores were not significantly different (Table 2).

Associations of OBS with prevalence of TD

In this study, weighted logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the relationship between OBS and the prevalence of TD. Table 3 summarizes the OR and 95% CI for this association across three models, all demonstrating a consistent inverse relationship between OBS and TD prevalence after adjusting for confounders.

In the unadjusted model (Model 1), the OR for continuous OBS and TD prevalence was 0.98 (95% CI 0.97–0.99) (Table 3). Participants in higher OBS tertiles had significantly lower TD prevalence compared to those in the lowest tertile (OR = 0.79, 95% CI 0.65–0.98). After adjusting for age and race in Model 2, the OR for continuous OBS was 0.98 (95% CI 0.97–1.00) (Table 3). OBS tertiles T2 and T3 had ORs of 0.94 (95% CI 0.77–1.16) and 0.86 (95% CI 0.70–1.06) (Table 3), respectively, showing a trend toward reduced TD risk with higher OBS.

In the fully adjusted model (Model 3), which adjusted for additional factors including age, race, PIR, education level, marital status, diabetes, hypertension, total energy intake, and seasonal timing of serum sample collection, the OR remained at 0.98 (95% CI 0.97–1.00) (Table 3). For OBS tertiles T2 and T3, the ORs in Model 3 were 1.00 (95% CI 0.80–1.26) and 0.92 (95% CI 0.69–1.21) (Table 3), respectively, indicating individuals in higher OBS tertiles had a significantly lower prevalence of TD compared to those in the lowest tertile. Furthermore, a linear inverse association between OBS and TD was further confirmed using spline smoothing fitting with an adjustment for age, race, PIR, education level, marital status, diabetes, hypertension, total energy intake, and seasonal timing of serum sample collection (Fig. 2).

Smoothed curve fitting analysis of OBS and the prevalence of TD. (A) Dose–response association between OBS and total testosterone level. (B) The association of the prevalence of TD with OBS score in logistic regression adjusting for age, race, PIR, education level, marital status, diabetes, hypertension, total energy intake, and seasonal timing of serum sample collection. The red solid and blue dotted lines represent the central risk estimates and 95% CIs.

In addition, stratified analyses indicated that the inverse association between OBS and TD prevalence remained consistent across subgroups stratified by age, race, PIR, education level, and marital status (Fig. 3). Specifically, when the subgroup analyses stratified by age (20–39, 40–64, and ≥ 65 years old), race (White, Black, Mexican, and other), PIR (≤ 1.3, 1.3–3.5, and > 3.5), education level (below high school, high school, and above high school), marital status (married or living with partner versus single), there was no difference in the association between total OBS and the prevalence of TD (P-interaction > 0.05, Fig. 3). Similarly, stratified analyses of lifestyle OBS showed no significant differences in its association with TD prevalence (P-interaction > 0.05, Fig. 4). Furthermore, sensitivity analyses showed that removal of diabetes, hypertension, and seasonal timing of serum sample collection did not significantly affect the TD prevalence (Supplementary Table S2).

Forest plot of stratified analysis in associations between OBS and the prevalence of TD. Adjusted for age, race, PIR, education level, marital status, diabetes, hypertension, total energy intake and seasonal timing of serum sample collection. aThe OR (95%CI) value of OBS T2. bThe OR (95%CI) value of OBS T3.

Forest plot of stratified analysis in associations between the lifestyle OBS and the prevalence of TD. Adjusted for age, race, total energy intake, PIR, education level, marital status, diabetes, hypertension and seasonal timing of serum sample collection. aThe OR (95%CI) value of lifestyle OBS T2. bThe OR (95%CI) value of lifestyle OBS T3.

Key OBS components associated with TD

To identify specific OBS components associated with TD, dietary OBS and lifestyle OBS were separately analyzed using logistic regression models (Table 3). Dietary OBS was inversely associated with TD in Model 1 (OR: 0.99, 95% CI 0.98–1.00, P < 0.05); however, this association was not significant in Model 2 (OR: 0.99, 95% CI 0.98–1.01, P = 0.32) or Model 3 (OR: 1.00, 95% CI 0.98–1.02, P = 0.93) (Table 3). Conversely, lifestyle OBS maintained a robust inverse association with TD across all models, with an OR of 0.85 (95% CI 0.81–0.90) in Model 3 (Table 3). Participants in higher lifestyle OBS tertiles exhibited significantly lower TD prevalence compared to those in the lowest tertile (OR = 0.55, 95% CI 0.43–0.69), highlighting the strong link between lifestyle OBS and TD prevalence.

Using LASSO regression, key OBS factors associated with TD prevalence were identified from 22 variables, including dietary components (e.g., carbohydrates, fiber, vitamins) and demographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex, race). The optimal penalty parameter (λ = 0.005258) was determined through tenfold cross-validation (Fig. 5A,B). The predictive nomogram model highlighted vitamin E, vitamin B6, niacin, iron, MEI, BMI, alcohol, and age as the primary predictors of TD identified by the LASSO regression (Fig. 5C). Among these factors, physical activity exerted the highest influence on the association with TD prevalence (Fig. 5C). The model’s discriminatory power was assessed using ROC curve analysis, yielding an AUC of 0.744 (95% CI 72.4–76.4%, Fig. 5D). At the optimal threshold of 0.363, the model achieved a sensitivity of 73.8% and a specificity of 62.6% (Fig. 5D). This result underscores the model’s adequate performance in distinguishing individuals with TD from those without TD based on OBS components.

LASSO regression analysis to identify key OBS components associated with TD. (A) Plot for LASSO regression coefficients. (B) Cross-validation plot for LASSO regression. (C) Nomogram model established for predicting the prevalence of TD based on the key OBS factors screened by LASSO regression. (D) ROC curve for evaluating the diagnostic power for TD of the nomogram model.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study utilized NHANES data to investigate the association between oxidative stress and TD in adult males. Our findings suggest that higher OBS, indicative of better oxidative balance, is inversely associated with TD prevalence, independent of demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical factors. Moreover, LASSO regression identified specific OBS components associated with TD prevalence, particularly physical activity, highlighting a potential link between oxidative balance and testosterone regulation among males.

It has been shown that oxidative stress contributes to male infertility (30–80% of cases) by lowering testosterone, disrupting the HPG axis, and impairing testicular function12,25. Our analysis of a nationally representative sample of U.S. adult males demonstrated a strong inverse association between OBS and TD prevalence. Across all regression models, higher OBS tertiles consistently correlated with reduced odds of TD. Consistent with our findings, a cross-sectional study demonstrates that low testosterone levels in male patients with type 2 diabetes are associated with increased oxidative stress, correlating with higher ROS production26. However, the causal relationship between oxidative stress and TD remains an area of ongoing investigation. Evidence from clinical and animal studies suggests a bidirectional interplay between oxidative stress and TD2,13. On one hand, oxidative stress can disrupt redox homeostasis, impairing steroidogenesis and reducing testosterone synthesis in Leydig cells13,27. On the other hand, diminished testosterone levels may exacerbate mitochondrial dysfunction and promote excessive ROS production in Leydig cells2. For instance, research using testicular feminized and castrated male mice has shown that TD induces oxidative stress in cardiomyocytes28. Furthermore, studies have indicated that testosterone supplementation mitigates oxidative damage by enhancing antioxidant enzyme activity and improving oxidative stress parameters across various tissues2. These findings highlight the intricate relationship between oxidative balance and testosterone regulation, emphasizing the need for further research into therapeutic strategies aimed at mitigating oxidative stress to support testosterone homeostasis.

Several risk factors may influence oxidative stress and testosterone levels29. Epidemiological studies have documented that community-dwelling men over the age of 30 experience an annual decline of 0.5–15% in circulating testosterone levels and a 2–3% decrease in free testosterone concentrations, highlighting the aging as a significant factor in the progressive decline of testosterone level30. In this study, participants with TD in this study were significantly older than their non-TD counterparts. To account for the potential confounding effect of age on the association between OBS and TD, stratified analyses were conducted and showed that the inverse association between OBS and TD persisted across age subgroups, as well as other stratified factors, including race, PIR, education level, and marital status. These findings underscore the broad applicability of the protective effect of higher OBS against TD across diverse demographic and socioeconomic groups. While some models for total OBS and dietary OBS exhibited marginal statistical significance in fully adjusted models, this attenuation may result from the inclusion of critical confounders such as socioeconomic factors and comorbid conditions (e.g., diabetes, hypertension). Further large-scale prospective studies are warranted to validate these associations and elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

We further investigated the role of dietary factors and lifestyle behaviors associated with oxidative stress in relation to low testosterone levels. In our analysis, although both dietary and lifestyle OBS were initially evaluated, only lifestyle OBS maintained a significant inverse association with TD after adjusting for confounders. Our finding underscores the critical influence of lifestyle factors, such as physical activity and BMI, in reducing TD prevalence. Notably, LASSO regression identified specific OBS components most strongly associated with TD risk, with physical activity exerting the highest influence. While the relative contributions of these components and their independent and interactive effects on oxidative stress and TD require further investigation, our findings are consistent with previous research. For example, a cross-sectional analysis of a nationally representative sample of U.S. adult males found that moderate-intensity physical activity was associated with lower odds of TD31. Similarly, a clinical trial involving 88 overweight or obese men demonstrated that a 12-week aerobic exercise program significantly increased serum total, free, and bioavailable testosterone levels32. Consistent with this, Giudice et al. reported that lower daily step counts, as measured by a waist-worn uniaxial accelerometer, were associated with an increased risk of TD10. One possible explanation for the physical activity, have a strong association with TD, is that physical activity has a direct and immediate influence on oxidative stress regulation and endocrine function, which may require long-term adherence to manifest measurable effects. Several mechanisms may underlie the relationship between physical activity and testosterone levels. Some studies suggest that increased caloric expenditure associated with physical activity helps restore the HPG axis, which is often disrupted in metabolic conditions such as obesity33,34. Furthermore, physical activity has been shown to alter the cortisol-to-fat ratio, thereby modulating LH secretion and enhancing testosterone production by mitigating negative feedback on the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis35. These findings highlight the multifaceted role of physical activity in maintaining testosterone levels and mitigating TD prevalence.

In addition to lifestyle factors, this study identified dietary antioxidants-such as vitamin E, vitamin B6, and niacin-as significant contributors to reducing the risk of TD. Consistent with these findings, existing research emphasizes the critical role of vitamins in regulating male reproductive health, particularly through their ability to mitigate oxidative stress36. Notably, vitamins E and C are recognized as key antioxidants that neutralize free radicals and enhance semen quality37. Vitamin E, a lipid-soluble compound comprising tocopherols and tocotrienols, cannot be synthesized by mammals and must be obtained through dietary sources37. Its antioxidant properties are crucial for protecting androgens from damage caused by ROS and lipid peroxidation38. Experimental studies in rats have demonstrated that vitamin E supplementation enhances testicular antioxidant capacity by regulating Hsp70-2 chaperone expression, thereby improving endocrine function and increasing testosterone levels39. However, in the present study, the lack of a consistent association between dietary OBS and TD in fully adjusted models highlights the complexity of interactions between dietary components and other confounding factors. One possible explanation is that OBS score distribution varies across age groups and racial/ethnic backgrounds. These findings suggest that while dietary antioxidants may play a role in oxidative balance, their impact on TD could be modulated by a range of interconnected variables, necessitating further investigation to elucidate these relationships.

This study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design precludes the ability to draw causal conclusions between OBS and TD. Although significant associations were identified, the directionality of this relationship remains uncertain, as reverse causation cannot be ruled out. To better understand the causal role of OBS in TD, prospective cohort studies and randomized controlled trials are essential. Second, despite thorough adjustments for potential confounders, residual confounding may still exist, particularly with respect to factors such as dietary adherence, stress levels, medication use (e.g., testosterone replacement therapy), and other hormonal disorders (e.g., thyroid dysfunction). These variables may have influenced the observed associations and warrant further exploration in future studies. Third, there is the potential for measurement bias in the self-reported dietary and lifestyle data, which may be subject to recall bias, social desirability bias, and reporting inaccuracies. To address this limitation, future studies should incorporate more objective measures and validate these findings in diverse populations. Fourth, the composite nature of the OBS scoring system, which encompasses a broad range of factors, may dilute associations, particularly in complex outcomes like TD. Finally, while morning serum testosterone measurements are considered the clinical standard, they may not fully capture diurnal variations in testosterone levels. Future studies incorporating multiple time-point measurements would help mitigate this variability and provide a more accurate assessment of testosterone levels over time.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates a significant inverse association between OBS and TD prevalence. Key lifestyle factors, including physical activity and BMI, alongside specific micronutrients, emerge as pivotal determinants of oxidative balance and TD prevalence. The nomogram model incorporating these predictors demonstrated moderate discriminatory ability in identifying individuals with TD. These findings indicate that optimizing oxidative balance through lifestyle and dietary modifications may play a role in TD management. Potential approaches include increasing physical activity, incorporating antioxidant-rich foods, and exploring targeted antioxidant supplementation. However, further research is required to validate these associations and assess the effectiveness of such interventions in clinical settings.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in NHANES at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.

References

Halpern, J. A. & Brannigan, R. E. Testosterone deficiency. JAMA 322(11), 1116 (2019).

Alonso-Alvarez, C. et al. Testosterone and oxidative stress: The oxidation handicap hypothesis. Proc. Biol. Sci. 274(1611), 819–825 (2007).

Garcia-Cruz, E. & Alcaraz, A. Testosterone deficiency syndrome: Diagnosis and treatment. Actas Urol. Esp. (Engl. Ed.) 44(5), 294–300 (2020).

Ketchem, J. M., Bowman, E. J. & Isales, C. M. Male sex hormones, aging, and inflammation. Biogerontology 24(1), 1–25 (2023).

Lokeshwar, S. D. et al. Decline in serum testosterone levels among adolescent and young adult men in the USA. Eur Urol. Focus 7(4), 886–889 (2021).

Gleicher, N., Kushnir, V. A. & Barad, D. H. Worldwide decline of IVF birth rates and its probable causes. Hum. Reprod. Open 2019(3), hoz017 (2019).

Mendiola, J. et al. Exposure to environmental toxins in males seeking infertility treatment: A case-controlled study. Reprod. Biomed. Online 16(6), 842–850 (2008).

Mehta, A. et al. Limitations and barriers in access to care for male factor infertility. Fertil. Steril. 105(5), 1128–1137 (2016).

Haring, R. et al. Prospective inverse associations of sex hormone concentrations in men with biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress. J. Androl. 33(5), 944–950 (2012).

Del Giudice, F. et al. Association of daily step count and serum testosterone among men in the United States. Endocrine 72(3), 874–881 (2021).

Seftel, A. D. Male hypogonadism. Part I: Epidemiology of hypogonadism. Int. J. Impot. Res. 18(2), 115–120 (2006).

Finkel, T. & Holbrook, N. J. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature 408(6809), 239–247 (2000).

Roychoudhury, S. et al. Environmental factors-induced oxidative stress: Hormonal and molecular pathway disruptions in hypogonadism and erectile dysfunction. Antioxidants (Basel) 10(6), 837 (2021).

Glover, F. E. et al. The association between caffeine intake and testosterone: NHANES 2013–2014. Nutr J 21(1), 33 (2022).

Skoracka, K. et al. Diet and nutritional factors in male (in)fertility-underestimated factors. J. Clin. Med. 9(5), 1400 (2020).

De Luca, M. N. et al. Oxidative stress and male fertility: Role of antioxidants and inositols. Antioxidants (Basel) 10(8), 1283 (2021).

Hernandez-Ruiz, A. et al. A review of a priori defined oxidative balance scores relative to their components and impact on health outcomes. Nutrients 11(4), 774 (2019).

Kwon, Y. J., Park, H. M. & Lee, J. H. Inverse association between oxidative balance score and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutrients 15(11), 2497 (2023).

Mulhall, J. P. et al. Evaluation and management of testosterone deficiency: AUA guideline. J. Urol. 200(2), 423–432 (2018).

Wen, H. et al. Association of oxidative balance score with chronic kidney disease: NHANES 1999–2018. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 15, 1396465 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. Association between the oxidative balance score and telomere length from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 1345071 (2022).

Song, L. et al. Association between the oxidative balance score and thyroid function: Results from the NHANES 2007–2012 and Mendelian randomization study. PLoS One 19(3), e0298860 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. The association between oxidative balance score and frailty in adults across a wide age spectrum: NHANES 2007–2018. Food Funct. 15(9), 5041–5049 (2024).

Zhou, N. et al. The dietary inflammatory index and its association with the prevalence of hypertension: A cross-sectional study. Front. Immunol. 13, 1097228 (2022).

Showell, M. G. et al. Antioxidants for male subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 12, CD007411 (2014).

Rovira-Llopis, S. et al. Low testosterone levels are related to oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and altered subclinical atherosclerotic markers in type 2 diabetic male patients. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 108, 155–162 (2017).

Banihani, S. A. Testosterone in males as enhanced by onion (Allium cepa L.). Biomolecules 9(2), 75 (2019).

Zhang, L. et al. Testosterone suppresses oxidative stress via androgen receptor-independent pathway in murine cardiomyocytes. Mol. Med. Rep. 4(6), 1183–1188 (2011).

Leisegang, K. et al. The mechanisms and management of age-related oxidative stress in male hypogonadism associated with non-communicable chronic disease. Antioxidants (Basel) 10(11), 1834 (2021).

Salonia, A. et al. Paediatric and adult-onset male hypogonadism. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 5(1), 38 (2019).

Wu, S. et al. Dose–response association between 24-hour total movement activity and testosterone deficiency in adult males. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 14, 1280841 (2023).

Kumagai, H. et al. Vigorous physical activity is associated with regular aerobic exercise-induced increased serum testosterone levels in overweight/obese men. Horm. Metab. Res. 50(1), 73–79 (2018).

Morelli, A. et al. Physical activity counteracts metabolic syndrome-induced hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and erectile dysfunction in the rabbit. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 316(3), E519–E535 (2019).

Corona, G. et al. Body weight loss reverts obesity-associated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 168(6), 829–843 (2013).

Cano Sokoloff, N., Misra, M. & Ackerman, K. E. Exercise, training, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in men and women. Front. Horm. Res. 47, 27–43 (2016).

Minguez-Alarcon, L. et al. Dietary intake of antioxidant nutrients is associated with semen quality in young university students. Hum. Reprod. 27(9), 2807–2814 (2012).

Ferramosca, A. & Zara, V. Diet and male fertility: The impact of nutrients and antioxidants on sperm energetic metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(5), 2542 (2022).

Yue, D. et al. Effect of vitamin E supplementation on semen quality and the testicular cell membranal and mitochondrial antioxidant abilities in Aohan fine-wool sheep. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 118(2–4), 217–222 (2010).

Khosravanian, N. et al. Testosterone and vitamin E administration up-regulated varicocele-reduced Hsp70-2 protein expression and ameliorated biochemical alterations. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 31(3), 341–354 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the invaluable contributions of all NHANES participants.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L.,C.M., J.Q. and P.Z. designed the project of this manuscript. J.L., C.M. and Y.L. contributed to statistical analyses and results interpretation. J.L. and C.M. contributed to the manuscript draft. J.Q. and P.Z. revised the paper. All authors edited and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Ma, C., Leng, Y. et al. Association between the oxidative balance score and testosterone deficiency: a cross-sectional study of the NHANES, 2011–2016. Sci Rep 15, 8040 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92934-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92934-5