Abstract

Trusting the decisions of deep learning models requires transparency of their reasoning process, especially for high-risk decisions. In this paper, a fully transparent deep learning model (Shallow-ProtoPNet) is introduced. This model consists of a transparent prototype layer, followed by an indispensable fully connected layer that connects prototypes and logits, whereas usually, interpretable models are not fully transparent because they use some black-box part as their baseline. This is the difference between Shallow-ProtoPNet and prototypical part network (ProtoPNet), the proposed Shallow-ProtoPNet does not use any black box part as a baseline, whereas ProtoPNet uses convolutional layers of black-box models as the baseline. On the dataset of X-ray images, the performance of the model is comparable to the other interpretable models that are not completely transparent. Since Shallow-ProtoPNet has only one (transparent) convolutional layer and a fully connected layer, it is the shallowest transparent deep neural network with only two layers between the input and output layers. Therefore, the size of our model is much smaller than that of its counterparts, making it suitable for use in embedded systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The transparency of a deep learning model’s reasoning process is important in addition to its performance in usual metrics. Cynthia1 explains the need to design transparent/interpretable models. Also, she points out that the practice of explaining black-box models instead of designing interpretable models can put society in greater trouble. The use of black-box models in decision-making, especially for high-stakes decisions, has raised significant concerns about the trustworthiness of these models. Occasionally, erroneous data fed into these models has gone unnoticed, resulting in unjustly long prison sentences. One notable case involves inmate Glen Rodriguez, who was denied parole due to an incorrect COMPAS score2.

In this paper, a deep learning model shallow prototypical part network (Shallow-ProtoPNet) is proposed.

The Shallow-ProtoPNet is not only an interpretable model but also a fully transparent model. Unlike the other interpretable models, the Shallow-ProtoPNet does not use any black-box model as its baseline, it consists of a prototype layer and an indispensable fully-connected layer.

Shallow-ProtoPNet is based on the ProtoPNet structure. The ProtoPNet was presented by Chen et al.3, incorporating interpretability, where the comparison of image parts with learned prototypes is used to reason about the classification of new examples. The Shallow-ProtoPNet is the shallowest transparent model because it uses one transparent layer and one indispensable dense layer.

Since there are only two layers to train, the Shallow-ProtoPNet performs well on a relatively small dataset. Therefore, proposed model can be considered a step toward building deeper and fully transparent deep learning models4. We trained and tested our model over the dataset of chest X-ray images because transparency in the classification of medical images is more desired.

In artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted medical diagnostics, transparency, often referred to as interpretability or explainability, is crucial for several reasons. It enables healthcare professionals to comprehend the decision-making processes of AI models, fostering trust and facilitating informed clinical decisions. Transparent AI systems allow clinicians to understand how and why a particular diagnosis or recommendation is made, which is essential for validating the AI’s results and integrating them effectively into patient care5.

Related work

While various methods for model explanation have been developed, few approaches incorporate domain knowledge to enhance the user’s understanding of these explanations. Confalonieri et al.6 introduced the Trepan Reloaded, which builds upon the Trepan algorithm to generate surrogate decision trees from black-box models. Their method’s key contribution is integrating ontologies structured representations of domain-specific knowledge into the explanation process, which aims to improve the human interpretability of the generated decision trees. The results demonstrate that decision trees, which incorporate domain knowledge, are significantly more understandable to users compared to those generated by the standard Trepan algorithm.

Stiglic et al.7 emphasizes that higher interpretability enhances the comprehension and explanation of predictions, which is crucial for healthcare professionals who rely on data-driven insights to make personalized, informed decisions. These interpretable models facilitate a better understanding of patient-specific outcomes and treatment recommendations, ultimately contributing to improved healthcare service quality. According to Hassija et al.8 there are several needs to have interpretable models that motivate its development such as the understanding of why explainability matters, the need for reasoning, innovation, regulation, and advancement.

The foremost technique that is used for the interpretation of a deep learning model is posthoc interpretation9. Under posthoc interpretability analysis, the interpretations of the reasoning process of a model are made after the classifications are made by the model. These posthoc methods cannot fully explain the reasoning of their classifications.

Examples of posthoc interpretations include saliency visualization such as utilizing a low-light image salient object detection model10, applying a two-stage group semantics propagation mechanism11, or considering many regularization techniques that come together to create visualizations that are qualitatively clearer and easier to understand12. The posthoc also includes activation maximization via deep generator network13, convolutional deep belief networks14, or deep visualization15, or even through deconvolution such as multiple max-pooling modules16, and deep recursive convolution networks17.

This study is related to attention-based interpretation techniques that attempt to highlight the patches of an input image that are focal points of the neural network. However, these models do not provide prototypes that represent their focal points. Examples of attention-based interpretation techniques include class activation maps such as using cam-guided multi-path decoding presented by Lin et al.18 or augmented score-cam explained by Ibrahim et al.19. Other attention-based interpretation methods include part-based models considering feature hierarchies20, activation constellations21, region-based convolutional neural networks22, or considering multi-attention convolutional neural networks23.

Transformer models are increasingly being used to improve image classification capabilities in this context24, these new techniques are especially successful with low-light images25, being applied to real images26.

This work is also related to case-based classification techniques that use prototypes like the work presented by Bien and Tibshirani27, considering class cover catch digraphs28, or based on k-nearest neighbors for depth and image estimations29, local constrained representation30, or for learning a nonlinear embedding31.

Li et al.32 introduced a model that uses a decoder, while Chen et al. enhanced it by creating a model called ProtoPNet3, and Shallow-ProtoPNet is closely related to ProtoPNet. ProtoPNet model has some variations, such as: Quasi-ProtoPNet33, Gen-ProtoPNet34, Comb-ProtoPNet35, Ps-ProtoPNet36, Semi-ProtoPNet37, and NP-ProtoPNet38. Each of these ProtoPNet models uses a black-box part as a baseline. Semi-ProtoPNet is a non-interpretable model.

Although ProtoPNet, Gen-ProtoPNet, Quasi-ProtoPNet, NP-ProtoPNet, Ps-ProtoPNet, and Comb-ProtoPNet are interpretable models, they are not fully transparent models, because they use black-box models as their baselines.

We considered the original ProtoPNet, NP-ProtoPNet, Gen-ProtoPNet, Ps-ProtoPNet, and Quasi-ProtoPNet for a comparative analysis. The following non-interpretable models were assumed as the baselines: Visual geometry group (VGG)-1639, VGG-1940, residual neural network (ResNet)-3441, ResNet-15242, dense convolutional network (DenseNet)-12143, and DenseNet-16144.

Methodology

In this section, we present and elucidate the architecture and the training process of Shallow-ProtoPNet. This section also contains information about the dataset used in this study.

Shallow-ProtoPNet architecture

As shown in Fig. 2, Shallow-ProtoPNet consists of a generalized convolutional layer45 p of prototypes and a fully-connected layer f. The layer f has no bias, but it has a weight matrix \(f_m\). Therefore, the input layer is followed by the layers p, f, and logits. Hence, the architecture of Shallow-ProtoPNet is similar to the architecture of ProtoPNet as described in “Working principal of ProtoPNet” section, but Shallow-ProtoPNet does not use the negative reasoning process as recommended by 33, Theorem 3.1. Note that, layer p is an interpretable as well as a transparent layer, whereas layer f is an indispensable fully-connected layer. The layer p is a transparent layer, because we can even manually see the prototypes (which are used to make predictions) along with their similarity scores for a given input image, see Fig. 1.

To classify an input image, the model finds the Euclidean distance between each latent patch of the input image and the learned prototypes of images from different classes. The maximum of the inverted distances between a prototype and the patches of the input image is called the similarity score of the prototype. Note that the smaller the distance, the larger the reciprocal, and there will be only one similarity score for each prototype. Then the vector of similarity scores is multiplied with the weight matrix associated with the dense layer f to obtain logitis, which are normalized using Softmax to determine the class of the input image.

Prototypes are similar to certain patches of training images that give very high similarity scores. The main difference of Shallow-ProtoPNet from the other ProtoPNet models is that it does not use any black-box part as its baseline, whereas each of the other ProtoPNet models is constructed over the pretrained black-box base models. For comparison purposes, as mentioned in “Dataset” section, we used the same resized images for all the models.

ProtoPNet model series does not use fractional pooling layers (before the generalized convolution layer p) that can deal with variable input image size, but it uses the convolutional layers, specifically convolutional layers of ResNet, DenseNet, and VGG which require a fixed input image size. This is evidenced in the work of Gautam et al.46, who used the ResNet-34 model, in the work of Wei et al.47 who applied the ResNet-152, and finally in the work of Ukai et al.48.

Training of shallow-ProtoPNet

Let \(x_i\) and \(y_i\) be the training images and their labels, for \(1\le i\le n\), where n is the size of the training set. Let \(P_i\) denote the set of prototypes for class i, and let P represent the set of all prototypes. Let \(d^2\) be the square of the Euclidean distance d between the tensors: prototypes and patches of x. Our goal is to solve the following optimization problem:

where CC is given by

Let x be an input image of the shape \(3\times 224 \times 224\) and \(p^i_j\) be any prototype of the \(3 \times h\times w\), where \(1< h,~ w < 224\), that is, h and w are not simultaneously equal to 1 or 224. However, for our experiments, we used prototypes with spatial dimensions \(70 \times 100\), and each class has 10 prototypes. Suppose \(p^1_1, \cdots , p^1_{10}\), \(p^2_1, \cdots , p^2_{10}\) and \(p^3_1, \cdots , p^3_{10}\) are prototypes for the first, second, and third classes, respectively, where \(p^i_j\) is an ith prototype of jth class.

As shown in Fig. 2, an input image x is first fed to the generalized layer p to calculate similarity scores, and then those similarity scores are connected to the logits using a dense layer f. These logits are normalized using Softmax to find the probabilities to make predictions. These predictions are compared with the y labels to calculate the cross-entropy. The object function given in Equation (1) minimizes cross-entropy over sets of prototypes P, that is, after optimization, the objective function gives the prototypes that minimize the cross-entropy.

A prototype \(p^i_j\) has the same depth as the input image x, but its spatial dimensions \(h\times w\) are smaller than the input image’s spatial dimensions \(224\times 224\). Therefore, \(p^i_j\) can be considered a patch of x. As explained in “Working principal of ProtoPNet” section, Shallow-ProtoPNet also calculates the similarity scores. The model identifies a patch on x that is the most similar (with a higher similarity score) to the prototype \(p^i_j\). That is, for each prototype, the model produces a similarity score and it identifies a similar patch on x. Note that, at this step Shallow-ProtoPNet strikingly differs from the other ProtoPNet models.

Other ProtoPNet models compare a prototype with a latent patch of x instead of a patch of x, where a latent patch is a part of the output of a baseline of the other ProtoPNet models. Therefore, Shallow-ProtoPNet does not lose any information between x and p due to the convolutional layers or pooling layers of any baseline. In Fig. 2, the similarity scores 0.13828, 0.08940, and 0.05628 for \(p^1_1\), \(p^2_1\) and \(p^3_{10}\) are given, but the similarity score for each prototype is calculated. Let S be the matrix of similarity scores. The logits are obtained by multiplying S with \(f_m\), that is, the logits are the weighted sums of similarity scores. The logits 1.3149, 0.7712, and 0.6365 for the three classes are given in Fig. 2. The patches in the source images that are most similar to the prototypes \(p^1_1, p^1_{10}\), \(p^2_1, p^2_{10}\), \(p^3_1\) and \(p^3_{10}\) are enclosed by the green rectangles.

From Equation (1), we see that the lower cross entropy (CE) is necessary for better classification. To cluster prototypes around their respective classes, cluster cost (CC) must be smaller, see Equation (2). Since the number of classes (Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)49, Normal, and Pneumonia) is small, we only use the positive reasoning process similar to Quasi-ProtoPNet, see33, Theorem 3.1. For a class i, \(f^{(c,j)}_m = 0\) and \(f^{(i,j)}_m = 1\), where \(p_c \not \in P_i\), \(p_j \in P_i\), and \(f^{(r,s)}_m\) is the (r, s) entry of the weight matrix \(f_m\). Therefore, a prototype has a positive connection with its correct class and zero connection with its incorrect classes. The hyperparameter \(\lambda\) is set equal to 0.9. The optimizer stochastic gradient descent50 is used to optimize the parameters.

Visualization of prototypes

For a prototype and a training image x, Shallow-ProtoPNet identifies a patch on x that yields a similarity score at least at the 95th percentile of all the similarity scores, and the identified patch is projected to visualize the prototype. Also, each prototype is updated with the most similar patch of x, that is, the value of each prototype is replaced with the value of the most similar patch of x. Since these projected patches are similar to the prototypes, we also call the projected patches prototypes, see Fig. 1.

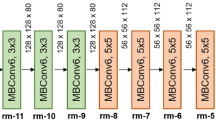

Working principal of ProtoPNet

The architecture of ProtoPNet (https://github.com/cfchen-duke/ProtoPNet) consists of the convolutional layers of a baseline, such as VGG-16, followed by some additional \(1\times 1\) convolutional layers for fine-tuning. Then, it has a generalized51 convolutional layer of prototypical parts (prototypes), and a fully-connected layer that connects prototypical parts to logits. Each prototypical part is a tensor with spatial dimensions \(1\times 1\) and a depth equal to the depth of the convolutional layers. Therefore, the layer of prototypical parts is a vector of tensors.

ProtoPNet compares learned prototypical parts with latent patches of an input image to make the classification.

The ProtoPNet uses the similarity scores in the classification process since Shallow-ProtoPNet is a sub-class of the ProtoPNet, this model also follows this approach. In Fig. 1 an example of the classification process is presented considering the similarity scores when the Shallow-ProtoPNet is applied.

The similarity score of a prototype with an input image is the maximum of the reciprocals of the Euclidean distances between the prototype and each latent patch of the input image. ProtoPNet applies log function as a non-linearity on similarity scores. The weighted sums of similarity scores give logits. At the fully connected layer, a positive weight of 1 is assigned between the similarity scores of prototypes and their correct classes, and a negative weight of \(-0.5\) is assigned between the similarity scores of prototypes and their incorrect classes.

The negative weights are assigned to scatter prototypes away from the classes they do not belong, that is, to incorporate the negative reasoning process. On the other hand, the positive weights are assigned to cluster the prototypes around their correct classes, that is, to incorporate the positive reasoning process. Softmax is used to normalize the logits. Being closely related to ProtoPNet, our model Shallow-ProtoPNet functions similar to ProtoPNet.

Novelty of Shallow-ProtoPNet

The novelty of our model is that it is not only an interpretable model but also a transparent model. Shallow-ProtoPNet uses similarity between prototypes and patches of training images, where the classes of training images are known. Therefore, Shallow-ProtoPNet is an interpretable model because it tells that a classified image contains patches more similar to the patches of images of the class, see Fig. 1. Our model is transparent because it does not use any black-box model as a baseline, see Fig. 2.

The other ProtoPNet models, on the other hand, rely on pretrained black-box models as their baselines, so they are not transparent. Also, our model does not apply any non-linearity to similarity scores, unlike the other ProtoPNet models. Additionally, our model only uses the positive reasoning process as recommended by33, Theorem 3.1, and it uses prototypes with spatial dimensions greater than 1.

The transparency or interpretability of a model becomes essential when the model is to be used for high-risk decisions. Shallow-ProtoPNet is not more accurate than the other ProtoPNet models, but it is more transparent. Besides being a step towards developing deeper and more transparent models, Shallow-ProtoPNet has the following advantages:

-

1.

The size of Shallow-ProtoPNet is much smaller than those of its related models. For example, Shallow-ProtoPNet can be as small as 50 KB, while the other ProtoPNet models have a minimum size of 28,000 KB, and some of them can even exceed 300,000 KB in size. Therefore, Shallow-ProtoPNet is suitable for use in embedded systems where memory size matters.

-

2.

Shallow-ProtoPNet performs well on a relatively small-sized dataset of X-ray images. The datasets collected by domain experts are typically small in size. In many cases, it is either too expensive or impossible to obtain abundant data, such as CT-scan or X-ray images of rare diseases or such images at the early stages of an epidemic.

Dataset

In this work, we used the dataset of chest X-ray images of COVID-19 patients52, pneumonia patients, and normal people53. The pretrained base models for the other ProtoPNet models can only accept input images of the size \(224\times 224\). Therefore, after cleaning the data, the images were resized to \(224 \times 224\). The resized images were segregated into three classes: COVID-19, Normal, and Pneumonia.

The COVID-19 class has 1248 training images and 248 test images; the Normal class has 1341 training images and 234 test images, and the Pneumonia class has 3875 training images and 390 test images. However, this is still a reasonably unbalanced dataset. Moreover, this dataset is not too small for the given depth of our model. Furthermore, it is obvious that with only two layers, if we choose a large dataset, our model cannot outperform the other ProtoPNet models in terms of accuracy.

Results

In this section, we compare the performance of the models and conduct a statistical analysis.

Performance comparison

In this section, we compare the performance of Shallow-ProtoPNet with the performance of the other models. To measure the performance of the models, we use the usual metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, given by:

where the true positive (TP) and true negative (TN) are diagonal entries of the confusion matrix, whereas the false positive (FP) and false negative (FN) are off-diagonal entries of the confusion matrix.

F1-score being harmonic mean of precision and recall is given by:

Since TP and TN are calculated using only the diagonal entries of the confusion matrix, by (3), accuracy is independent of the choice of the positive class. However, FP and FN are the off-diagonal entries of a confusion matrix54. Therefore, precision, recall, and F1-score depend on the positive class, see (5). In this section, in total 37 models/versions have been compared over the dataset, see “Dataset” section.

The first column of Table 1 shows the baselines, while the second column shows the metrics that we used to evaluate the models. In the third column, the accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score given by Shallow-ProtoPNet are provided. These metrics are not changing with the change in the baselines, because Shallow-ProtoPNet does not use any baseline. However, for the other ProtoPNet models these metrics are changing with the change in the baseline, see columns 4 through 9 in Table 1.

For example, when VGG-16 is used as a baseline for the other ProtoPNet models, the accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score given by ProtoPNet, NP-ProtoPNet, Gen-ProtoPNet, Ps-ProtoPNet, Quasi-ProtoPNet and the baseline itself (base only) are 79.73, 0.87, 0.92, 0.89; 84.63, 0.97, 0.99, 0.97; 85.89, 0.99, 0.98, 0.98; 86.01, 0.99, 0.99, 0.99; 86.12, 0.98, 0.99, 0.98 and 82.45, 0.97, 0.98, 0.97, whereas the accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score given by our model Shallow-ProtoPNet are 86.24, 0.96, 0.94 and 0.95.

The models stabilize after a certain number of epochs, but the accuracy still remains fluctuating around the stabilized accuracy. This fluctuation is experienced by all the ProtoPNet models and even the base models: ResNet-34, ResNet-152, DenseNet-121, and DenseNet-161, but the accuracy stabilizes for VGG-16 and VGG-19.

The highest accuracy and F1-score corresponding to each base model is in bold in Table 1. Shallow-ProtoPNet wins in two cases among all the models, including non-interpretable base models. However, the performance of our model in other metrics does not seem to be impressive, while F1-score is also considered as an important metric besides accuracy. The reason for such a performance is the choice of the positive class and negative classes.

If we consider Normal as the first class, then the performance of our model in the metrics recall and F1-score becomes impressive, see Table 2. That is, our model is better at correctly identifying Normal class images. In Table 2, the highest F1-score corresponding to each base model is in bold. We observe that our model has a better F1-score than the other ProtoPNet models except NP-ProtoPNet with base VGG-19.

In Table 3, the highest F1-score corresponding to each base model is in bold. In the table, in some cases, the F1-score given by our model is lower than the F1-score given by the other ProtoPNet models by only a small difference, whereas in Table 2 its F1-score is higher than that of the other ProtoPNet models by a large margin except NP-ProtoPNet with base VGG-19. Therefore, Shallow-ProtoPNet performs well on the given dataset of X-ray images. However, Shallow-ProtoPNet is a fully transparent model in addition to being an interpretable model.

The macro-averaged F1-score (or macro F1-score) represents the arithmetic mean of all the per-class F1-scores. This metric provides a balanced assessment by treating all classes equally, regardless of their prevalence. In Table 4, the highest averaged-macro F1–score are in bold. From Table 4, we observe that the macro-averaged F1-score given by Shallow-ProtoPNet is lesser than the macro-averaged F1-score given by the other models with baselines VGG-19, ResNet-151, DenseNet-121, and DenseNet-161. However, the averaged-macro F1-score given by Shallow-ProtoPNet is higher than the averaged-macro F1-score given by the other models with baselines VGG-16 and ResNet-34.

The performance of Shallow-ProtoPNet is comparable with the other models. We remark that the averaged-macro F1-score is strongly correlated to accuracy. Moreover, as mentioned above, accuracy is independent of the choice of the positive class. Therefore, accuracy can also be considered a good metric to compare the performance of models for non-binary classification. Furthermore, in “Determination of statistically significantly differencein accuracies” section, we see that none of the other ProtoPNet models gives statistically significantly better accuracy than that given by our model.

Graphical comparison of the accuracies

Each of the other ProtoPNet models uses VGG-16, VGG-19, ResNet34, ResNet-152, DenseNet-121, and DenseNet-161 black-box model as a baseline. However, our model Shallow-ProtoPNet does not use any black box as a baseline. In Figs. 3, 4, 5, a graphical comparison of the accuracies is provided when different baselines are used. For example, in Fig. 3, accuracies of the models are compared when VGG-16 and VGG-19 are used as baselines as indicated by the titles of the subplots. A comparison of the accuracies is provided for 100 epochs, though the accuracies stabilize after 70 epochs.

Determination of statistically significantly difference in accuracies

We use the test of hypothesis related to the system of two proportions to show that the accuracy given by Shallow-ProtoPNet is not statistically significantly different from the accuracies given by the other models. Let n be the number of test images. Let \(m_1\) and \(m_2\) be the number of correctly classified images by any one of the other ProtoPNet models and Shallow-ProtoPNet, respectively. The Z-statistic is55:

\(\text{ where } p=(m_1+m_2)/2n, ~p_1=m_1/n \quad \text{ and } p_2=m_2/n.\) Our hypothesis are:

For the two-tailed hypothesis and significance level equal to 0.05, to accept the alternate hypothesis, the p-value needs to be less than 0.025. However, the p-value less than 0.025 can be obtained only if Z has the absolute value of at least 2.82. The accuracies in bold in Table 1 are given by NP-ProtoPNet with base VGG-19 (88.99), Quasi-ProtoPNet with base ResNet-152 (88.41 (=\(88.30+0.11\))), base model (Base only) DenseNet-121 (88.53 (=\(88.41+0.12\))) and base model (Base only) DenseNet-161 (\(88.65 = (88.42+0.23)\)) are higher than the accuracy given by Shallow-ProtoPNet (86.24), and even these four higher accuracies along with the accuracy given by Shallow-ProtoPNet give Z-statistic equal to 1.7431, 1.2905, 1.4401 and 1.5187, respectively.

None of the models listed in Tables 1, 2 and 3 has statistically significantly better accuracy than that given by our model Shallow-ProtoPNet. Hence the performance of Shallow-ProtoPNet is on par with the performance of the other ProtoPNet models.

Limitations

Since Shallow-ProtoPNet uses only two layers as mentioned above, the number of parameters to train is much less than the number of parameters of each of the other ProtoPNet models. Therefore, Shallow-ProtoPNet cannot outperform the other ProtoPNet models on large-sized datasets.

In addition, similar to the other ProtoPNet models, Shallow-ProtoPNet also experiences a decrease in accuracy when prototypes are replaced with the patches of training images, see Theorem 3, Theorem 2.1,33, Theorem 3.1 and36, Theorem 1.

Conclusions

The other ProtoPNet models are interpretable, but they still use a black-box part as their baseline. Therefore, the other ProtoPNet models are not fully transparent, whereas Shallow-ProtoPNet is a fully transparent model, because it does not use any black-box model as its baseline.

Compared to the other ProtoPNet models, Shallow-ProtoPNet has a very small size, so Shallow-ProtoPNet becomes a good candidate for use in embedded systems where memory is typically of small size. Shallow-ProtoPNet can have a size of 50 KB, while the other ProtoPNet models have a minimum size of 28000 KB, which is hundreds of times its size.

Although ProtoPNet cannot outperform the other ProtoPNet models on large-sized datasets, it performs well on the relatively small-sized dataset of X-ray images. Shallow-ProtoPNet can be useful for image classification tasks where the data collection cost is very high or the procurement of large datasets is not feasible. Since it is difficult to obtain abundant data related to rare and important events, for example, X-ray or CT-scan images related to a rare disease, Shallow-ProtoPNet can be useful for classification of images for such events where transparency of a model matters the most.

It only uses the positive reasoning process, as recommended by33, Theorem 3.1. However, Shallow-ProtoPNet can use prototypes of both shapes: rectangular and square. Since the spatial dimensions of the prototype lie between \(1\times 1\) and \(224 \times 224\), a large number of spatial dimensions are possible. Therefore, the optimal spatial dimensions have not yet been determined. In future work, we shall attempt to find theoretical bounds for optimal spatial dimensions. Also, we hope to make Shallow-ProtoPNet deeper with more transparent layers to make it suitable for large datasets. However, the insertion of more transparent layers is not trivial because each prototype produces only one number, the similarity score.

In summary, deep learning algorithms usually have pros and cons, and so does Shallow-ProtoPNet. However, the architecture of Shallow-ProtoPNet can be considered a step towards designing deeper and transparent models.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Gurmail Singh, upon reasonable request.

References

Rudin, C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1, 206–215. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-019-0048-x (2022).

Wexler, R. When a computer program keeps you in jail: How computers are harming criminal justice. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/13/opinion/how-computers-are-harming-criminal-justice.html. (Accessed 20 Jan 2024) (2017).

Chen, C. et al. This looks like that: Deep learning for interpretable image recognition. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 32, 1–12 (2019).

Singh, G., Stefenon, S. F. & Yow, K.-C. Interpretable visual transmission lines inspections using pseudo-prototypical part network. Mach. Vis. Appl. 34(3), 41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00138-023-01390-6 (2023).

Salahuddin, Z., Woodruff, H. C., Chatterjee, A. & Lambin, P. Transparency of deep neural networks for medical image analysis: A review of interpretability methods. Comput. Biol. Med. 140, 105111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.105111 (2022).

Confalonieri, R., Weyde, T., Besold, T. R. & Moscoso del Prado Martín, F. Using ontologies to enhance human understandability of global post-hoc explanations of black-box models. Artif. Intell. 296, 103471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artint.2021.103471 (2021).

Stiglic, G. et al. Interpretability of machine learning-based prediction models in healthcare. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 10(5), 1379. https://doi.org/10.1002/widm.1379 (2020).

Hassija, V. et al. Interpreting black-box models: A review on explainable artificial intelligence. Cogn. Comput. 16(1), 45–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12559-023-10179-8 (2024).

Ghosh, S., Yu, K. & Arabshahi, F. kayhan Batmanghelich: Bridging the gap: From post hoc explanations to inherently interpretable models for medical imaging. In ICML 3rd Workshop on Interpretable Machine Learning in Healthcare (IMLH) (2023)

Yue, H. et al. Salient object detection in low-light images via functional optimization-inspired feature polishing. Knowl.-Based Syst. 257, 109938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2022.109938 (2022).

Tan, Z. & Gu, X. Co-saliency detection with intra-group two-stage group semantics propagation and inter-group contrastive learning. Knowl.-Based Syst. 252, 109356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2022.109356 (2022).

Simonyan, K., Vedaldi, A. & Zisserman, A. Deep inside convolutional networks: Visualising image classification models and saliency maps. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 1–8 (ICLR, 2014).

Nguyen, A., Dosovitskiy, A., Yosinski, J., Brox, T. & Clune, J. Synthesizing the preferred inputs for neurons in neural networks via deep generator networks. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 29, 1–9 (2016).

Lee, H., Grosse, R., Ranganath, R. & Ng, A. Y. Convolutional deep belief networks for scalable unsupervised learning of hierarchical representations. In Annual International Conference on Machine Learning, vol. 26, 609–616 https://doi.org/10.1145/1553374.1553453 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2009).

Yosinski, J., Clune, J., Nguyen, A. M., Fuchs, T. J. & Lipson, H. Understanding neural networks through deep visualization. In International Conference on Machine Learning, vol. 31, 1–12 (2015).

You, H. et al. Mc-net: Multiple max-pooling integration module and cross multi-scale deconvolution network. Knowl.-Based Syst. 231, 107456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2021.107456 (2021).

Cao, F. & Chen, B. New architecture of deep recursive convolution networks for super-resolution. Knowl.-Based Syst. 178, 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2019.04.021 (2019).

Lin, D. et al. Cam-guided multi-path decoding u-net with triplet feature regularization for defect detection and segmentation. Knowl.-Based Syst. 228, 107272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2021.107272 (2021).

Ibrahim, R. & Shafiq, M. O. Augmented score-cam: High resolution visual interpretations for deep neural networks. Knowl.-Based Syst. 252, 109287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2022.109287 (2022).

Girshick, R., Donahue, J., Darrell, T. & Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, USA 580–587 https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2014.81 (2014).

Simon, M. & Rodner, E. Neural activation constellations: Unsupervised part model discovery with convolutional networks. In International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 1143–1151 https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2015.136 (2015).

Zhang, N., Donahue, J., Girshick, R. & Darrell, T. Part-based r-cnns for fine-grained category detection. In Computer Vision, vol. 12, 834–849. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-10590-1_54 (Springer, 2014).

Zheng, H., Fu, J., Mei, T. & Luo, J. Learning multi-attention convolutional neural network for fine-grained image recognition. In International Conference on Computer Vision, 5219–5227. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2017.557 (IEEE, 2017).

Xu, L. et al. Upt-flow: Multi-scale transformer-guided normalizing flow for low-light image enhancement. Pattern Recogn. 158, 111076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2024.111076 (2025).

Hu, C. et al. HSV-3S and 2D-GDA for high-saturation low-light image enhancement in night traffic monitoring. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 24(12), 15190–15206. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2023.3308894 (2023).

Xu, L. et al. Degrade for upgrade: Learning degradation representations for real-world low-light image enhancement. Comput. Electr. Eng. 119, 109622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2024.109622 (2024).

Bien, J. & Tibshirani, R. Prototype selection for interpretable classification. Ann. Appl. Stat. 5(4), 2403–2424 (2011).

Priebe, C. E., Marchette, D. J., DeVinney, J. & Socolinsky, D. A. Classification using class cover catch digraphs. J. Classif. 20, 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00357-003-0003-7 (2003).

Eshimiakhe, D. & Lawal, K. Application of k-means algorithm to Werner deconvolution solutions for depth and image estimations. Heliyon 8(11), 11665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11665 (2022).

Gou, J. et al. Locality constrained representation-based k-nearest neighbor classification. Knowl.-Based Syst. 167, 38–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2019.01.016 (2019).

Salakhutdinov, R. & Hinton, G. Learning a nonlinear embedding by preserving class neighbourhood structure. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, vol. 2, 412–419 (PMLR, 2007).

Li, O., Liu, H., Chen, C. & Rudin, C. Deep learning for case-based reasoning through prototypes: A neural network that explains its predictions. In AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence vol. 32, 3530–3537. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v32i1.11771 (2017).

Singh, G. Think positive: An interpretable neural network for image recognition. Neural Netw. 151, 178–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2022.03.034 (2022).

Singh, G. & Yow, K.-C. An interpretable deep learning model for covid-19 detection with chest x-ray images. IEEE Access 9, 85198–85208. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3087583 (2021).

Singh, G. One and one make eleven: An interpretable neural network for image recognition. Knowl.-Based Syst. 110926 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2023.110926 (2023).

Singh, G. & Yow, K.-C. Object or background: An interpretable deep learning model for covid-19 detection from CT-scan images. Diagnostics 11(9), 1732. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11091732 (2021).

Stefenon, S.F., Singh, G., Yow, K.-C. & Cimatti, A. Semi-protopnet deep neural network for the classification of defective power grid distribution structures. Sensors 22(13) https://doi.org/10.3390/s22134859 (2022).

Singh, G. & Yow, K.-C. These do not look like those: An interpretable deep learning model for image recognition. IEEE Access 9, 41482–41493. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3064838 (2021).

Ghosh, S., Chaki, A. & Santosh, K. Improved U-Net architecture with VGG-16 for brain tumor segmentation. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 44(3), 703–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13246-021-01019-w (2021).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. In International Conference on Learning Representations, vol. 3, 1–14 (2015).

Gao, M., Qi, D., Mu, H. & Chen, J. A transfer residual neural network based on ResNet-34 for detection of wood knot defects. Forests 12(2), 212. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12020212 (2021).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, USA, 770–778 https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.90 (2016).

Corso, M. P. et al. Evaluation of visible contamination on power grid insulators using convolutional neural networks. Electr. Eng. 105, 3881–3894. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00202-023-01915-2 (2023).

Huang, G., Liu, Z., Van Der Maaten, L. & Weinberger, K. Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, USA, 2261–2269 https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2017.243 (2017).

Ghiasi-Shirazi, K. Generalizing the convolution operator in convolutional neural networks. Neural Process. Lett. 50(3), 2627–2646. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11063-019-10043-7 (2019).

Gautam, S., Höhne, M.M.-C., Hansen, S., Jenssen, R. & Kampffmeyer, M. This looks more like that: Enhancing self-explaining models by prototypical relevance propagation. Pattern Recogn. 136, 109172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2022.109172 (2023).

Wei, Y., Tam, R. & Tang, X. MProtoNet: A case-based interpretable model for brain tumor classification with 3D multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging. In Medical Imaging with Deep Learning vol. 227, 1798–1812 (PMLR, 2024).

Ukai, Y., Hirakawa, T., Yamashita, T. & Fujiyoshi, H. Toward prototypical part interpretable similarity learning with protometric. IEEE Access 11, 62986–62997. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3287638 (2023).

Fernandes, F. et al. Long short-term memory stacking model to predict the number of cases and deaths caused by COVID-19. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 42(6), 6221–6234. https://doi.org/10.3233/JIFS-212788 (2022).

Wojtowytsch, S. Stochastic gradient descent with noise of machine learning type part I: Discrete time analysis. J. Nonlinear Sci. 33(3), 45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00332-023-09903-3 (2023).

Nalaie, K., Ghiasi-Shirazi, K. & Akbarzadeh-T. M.-R. Efficient implementation of a generalized convolutional neural networks based on weighted euclidean distance. In International Conference on Computer and Knowledge Engineering, vol. 7, 211–216. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCKE.2017.8167877 (IEEE, 2017).

Cohen, J. P., Morrison, P. & Dao, L. COVID-19 Image Data Collection. https://github.com/ieee8023/covid-chestxray-dataset (Accessed 24 Jan 2024) (2020).

Kaggle: Chest X-Ray (Pneumoina). https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/allen-institute-for-ai/CORD-19-research-challenge (Accessed 24 Jan 2024) (2024).

Li, S. et al. Application of semi-supervised learning in image classification: Research on fusion of labeled and unlabeled data. IEEE Access 12, 27331–27343. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3367772 (2024).

Yu, H. & Hutson, A. D. Inferential procedures based on the weighted Pearson correlation coefficient test statistic. J. Appl. Stat. 51(3), 481–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/02664763.2022.2137477 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the University of Regina for providing them access to the computational resources to run the experiments.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), funding reference number DDG-2024-00035. Cette recherche a été financée par le Conseil de recherches en sciences naturelles et en génie du Canada (CRSNG), numéro de référence DDG-2024-00035.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Gurmail Singh - wrote the introduction, method, results, and conclusion sections, drew the figures, and computed the experiments; Stefano Frizzo Stefenon and Kin-Choong Yow - proofread.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests:

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, G., Stefenon, S.F. & Yow, KC. The shallowest transparent and interpretable deep neural network for image recognition. Sci Rep 15, 13940 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92945-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92945-2