Abstract

Professional foster families for dependent older adults are a housing model perceived as an alternative to nursing homes in the French West Indies. The clinical profile of older adults in foster families remains to be determined, particularly concerning neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) in the presence of major cognitive disorders. In this cross-sectional analysis from twin studies conducted in foster families (n = 107, mean age: 81.8 years, male/female ratio: 38/62) and nursing homes (n = 332; (mean age: 81.3 years, male/female ratio: 51/49), we compare the prevalence and severity of NPS, along with psychotropic drugs prescription, between older adults (≥ 60 years) living in both arrangements. The prevalence of major cognitive disorders and the total number of NPS (3.4 ± 2.7 in foster families vs. 3.4 ± 2.5; p = 0.946) were similar between the two groups. The prevalence of each NPS was similar except for apathy (20.0% in nursing homes vs. 8.5% in foster families, p = 0.006), aberrant motor behavior (22.1% in nursing homes vs. 36.2% in foster families, p = 0.004) and eating disorders and appetite (23.0% vs. 9.3%, respectively, p = 0.002). The use of antipsychotics was more frequent in nursing homes (36.7% vs. 26.2%, p = 0.046). This study suggests that the foster families’ environment may be well suited for managing older adults with psycho-behavioral disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The most daunting demographic challenge the world faces today is no longer population growth but rather population aging. High-income countries are already experiencing significant demographic changes, such as Japan, where 30% of the population is over 60 years old. However, it is now low- and middle-income countries that are undergoing the most substantial demographic shifts. By 2050, 80% of individuals over 60 years old will reside in low- and middle-income countries1. Low and middle-income countries are seeking care and housing models that do not always align with those used in high-income countries, due to financial or cultural reasons. In these countries, older adults who become dependent are most often cared for by family or close relatives, with nursing homes being underdeveloped or nonexistent. However, these countries are expected to face a substantial increase in the number of individuals with dementia. Projections suggest that the number of individuals with dementia will increase by 367% by 2050 in North Africa and the Middle East, and by 357% in Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa2. Many governments are grappling with how best to develop effective policies and programs to address the needs of aging populations, including the rapidly growing demand for long-term care. In this context, professional foster families for the dependent older adults could be a potentially underexplored alternative to nursing homes3. This is a widely used care model in the French Caribbean Islands (Guadeloupe and Martinique), fully funded by public authorities, to address the shortage of nursing homes. Each foster family cares for one to three residents, providing a room in their home, meals, and daily activities. Medical oversight is provided by a nurse who visits the family at least once a day. In a previous study4, we compared the baseline characteristics of residents in foster families and nursing homes using data from two cohort studies, the KASAF (KArukera Study of Aging in Foster Families) study and the KASEHPAD (KArukera Study of Aging in EHPAD, i.e. nursing homes) study. We observed that the profile of older adults in foster families was similar to that of those in nursing homes in terms of age. Residents in nursing homes were more often male and had a lower level of dependency. Cognitive status was similar between the two housing models, with three-quarters of residents exhibiting major cognitive disorders based on Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) scores (≤ 18).

Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia are a significant source of suffering for patients with cognitive disorders, their families, caregivers, and healthcare providers5. Additionally, from the age of 70, aging-related conditions can intertwine with existing neuropsychiatric disorders. Indeed, neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) can occur in 50–98% of patients with dementia living in the community6. NPS refer to a wide range of symptoms including depression, anxiety, apathy, agitation, irritability, persistent complaints, delusions, hallucinations, disinhibition, and disturbances in sleep or appetite. Such NPS worsen prognosis and accelerate progression to severe Alzheimer’s dementia and death7, and are associated with impaired quality of life in nursing homes8. Additionally, NPS are a frequent cause for institutionalization in high incomes countries9. Effective pharmaceutical interventions or non-pharmacological therapies for NPS remain limited. Admission to nursing homes is associated with an increase in the use of antidepressants, anxiolytics, and hypnotics10,11. Additionally, NPS are associated with increased caregiver burden12.

Professional foster families care for older adults with dependency issues who may experience NPS. In the perspective of assessing whether foster family’s model is a relevant model for housing and caring for older adults with dementia and/or disability, it is crucial to determine the prevalence of these NPS within foster families’ settings and to compare it with that observed in nursing homes. These symptoms can be challenging to manage for foster caregivers, especially since they are not necessarily healthcare professionals. Indeed, less than half of the professional foster caregivers had backgrounds in healthcare4. Estimating the prevalence of NPS in foster families setting could be valuable for training foster caregivers to better identify and manage these symptoms and potentially to draw inspiration from practices implemented in nursing homes. Additionally, the use of pharmacological treatment might differ, as residents in foster families are typically monitored by a general practitioner, while residents in nursing homes are usually overseen by a nursing home medical coordinator. The objective of this study was to compare the prevalence of NPS between residents living in foster families and those living in nursing homes, as well as to compare the use of psychotropic medication in these two models.

Methods

The data pertain to the baseline characteristics of older adults from the KASAF4 and KASEPHAD13 studies. In summary, these are twin studies with the primary objective of comparing the hospitalization rates of residents in foster care versus nursing homes over one year. To be eligible, participants had to be 60 years of age or older, residing in a foster family in Guadeloupe or a nursing home in the French West Indies, and covered by French social security. The exclusion criterion was refusal by the resident or their legal guardian to participate in the study. At baseline, a dedicated geriatrician or clinical research nurse conducted interviews with the participants in both foster families and nursing homes, as well as with their caregivers. The KASAF study recruited 107 residents from 56 foster families during the inclusion period from September 2020 to May 2021. The KASEPHAD study recruited 332 elderly individuals from 6 nursing homes between September 2020 and November 2022.

Ethics

The KASEHPAD study was registered under RGB-ID: 2020-A00960-39. The protocol for the KASAF study has been published14 and is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04545775). The KASAF study received approval from the French Sud Méditerranée III Ethics Committee on July 1, 2020. The EST 1 French Ethics Committee approved the KASEHPAD study on June 2, 2020. The study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov on October 13, 2020 (NCT04587466). All the participants or their legal guardians signed informed consent forms for participation and publication, and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Measures

NPS were measured using the Neuro-Psychiatric Inventory-Q (NPI-Q)15. The results of the NPI-Q correlate with those of the longer version16, though it requires less time to administer15. This NPI scale assesses 12 behavioral domains: delusions, hallucinations, agitation and aggression, depression and dysphoria, anxiety, euphoria and elation, apathy and indifference, disinhibition, irritability and lability, aberrant motor behavior, nighttime behavioral disturbances, and appetite and eating changes. For each domain, the informant was asked to provide ratings for the frequency (present or absent) and severity (on a 3-point Likert-type scale) of symptoms experienced in the past week. A total score ranging from 0 to 12 was calculated, along with a total severity score ranging from 0 to 36. The NPI-R symptoms were also analyzed both individually and in clusters. The psychotic cluster includes delusions, hallucinations, and agitation.

Cognitive performance was assessed using the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) tool17 generating a score from 0 to 30, where a low score indicates poor cognitive function. The Katz Activities of Daily Living (ADL) was used to assess functional status18. Katz’s scale comprises six items assessing independence in basic activities of daily living: bathing, toileting, eating, locomotion, dressing, and incontinence. For each activity, a score of 1 indicates complete autonomy, a score of 0.5 indicates partial autonomy, and a score of 0 indicates complete dependency.

The following variables were also extracted: age, gender, marital status, education, duration of stay in foster families or nursing homes, Gerontology Iso-Ressources (GIR) score at entry, comorbidities and psychiatric drugs. The level of dependency upon admission into foster care or nursing homes was extracted from the data files using the Autonomy, Gerontology Iso-Ressources (AGGIR) questionnaire. In France, the AGGIR questionnaire was developed by public authorities to rapidly assess the dependency level of older adults and to classify them into a specific dependency group, ranging from GIR 0 (bedridden, fully dependent) to GIR 6 (no assistance required, fully autonomous in daily activities). The GIR scores were categorized into three classes: severe dependency (GIR 1 or 2), moderate dependency (GIR 3 and 4), and low dependency (GIR 5 or 6).

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), median and interquartile range (IQR). Qualitative variables were expressed as percentages. Fisher and Wilcoxon tests were used to compare quantitative variables between residents in foster families and nursing homes and chi-test for qualitative variables. The severity of NPS symptoms was analyzed as a dichotomous variable: no or low severity was grouped as “severity = no” and “moderate” to “high” as “severity = yes. Missing data were not imputed. All analyses were performed with R v.4.2.1 software.

Results

A total of 439 older adults living in Caribbean nursing homes (n = 332) or foster families (n = 107) were included. There were no differences observed in age, marital status, education, diabetes, cardiovascular history, stroke, MMSE score ≤ 18 and chronic pain. There were more male in nursing homes compared to foster families (50.6% compared to 38.3%; p = 0.027), more hypertension (67.0% versus 45.8%; p < 0.001). More older adults were severely dependent at entry into nursing homes (37.4% compared to 17.9%) and the ADL score at inclusion was lower in foster families (Median score: 0.5 versus 2; p < 0.001) (Table 1).

Comparison of NPS between residents in nursing homes and foster families

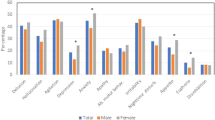

The total NPI score was similar between older adults in nursing homes and foster families (3.4 ± 2.7 compared to 3.4 ± 2.5; p = 0.946). In addition, 338 participants (81.1%) exhibited at least one NPS, including 87 (82.9%) in foster families and 251 (80.4%) in nursing homes. The prevalence of each NPS was similar between the groups, except for apathy (20.0% in nursing homes versus 8.5% in foster families, p = 0.006), aberrant motor behavior (22.1% in nursing homes versus 36.2% in foster families, p = 0.004), and eating disorders and appetite changes (23.0% in nursing homes versus 9.3% in foster families, p = 0.002) (Table 2).

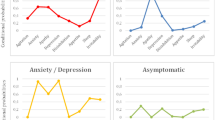

The total severity score of NPI was higher in nursing homes (6.8 ± 4.9) compared to foster families (5.2 ± 3.2, p = 0.007). The proportion of residents with moderate or severe symptoms (compared to no or low severity) was greater in nursing homes for anxiety (22.2% versus 1.9% in foster families, p < 0.001), apathy (12.3% versus 1.9%, p = 0.001), irritability (15.9% versus 6.6%, p = 0.006), and eating disorders and appetite changes (10.4% versus 1.9%, p = 0.005).

The prevalence of the psychotic cluster (delusions, hallucinations, and agitation) was similar between both groups, but the severity score was higher in nursing homes (3.4 ± 2.1) compared to foster families (2.7 ± 1.7, p = 0.011).

Comparison of psychiatric medications between older adults living in nursing homes and in foster families

The number of medications, including psychotropic drugs, was similar between both groups. Anxiolytic drugs were more frequently used in foster families (40.2% compared to 28.3%, p = 0.021), while antipsychotic drugs were less commonly used (26.3% vs. 36.7%, p = 0.046). There were no significant differences in the use of antidepressants, total psychotropic drugs, or antiepileptics (Table 3). Among the 257 participants in the delusion/hallucination/agitation cluster, 114 (44.4%) were on antipsychotics. In foster care, only 22 (30.1%) of the 73 older adults were taking antipsychotics, compared to 92 out of 183 (50.3%) in nursing homes.

Comparison of NPS between residents diagnosed with dementia in nursing homes and foster families

A total of 226 older adults with a diagnosis of dementia were included in the study. The primary etiological diagnoses were Alzheimer’s disease (35.4%), vascular dementia (10.2%), and Parkinson’s disease dementia (9.3%). Only three cases of dementia with Lewy bodies were identified, all in nursing homes. In 30.5% of residents, the specific type of dementia was not reported (Appendix S1).

The results observed in residents with a diagnosis of dementia were consistent with those for the overall cohort. The total number of NPS was similar between residents in foster families and nursing homes (3.9 ± 2.5 vs. 3.9 ± 2.6, respectively; p = 0.948). A significantly higher prevalence of apathy (7.7% vs. 24.0%; p = 0.010) and loss of appetite (13.2% vs. 29.6%; p = 0.017) was observed in nursing home residents. One notable difference compared to the previous analysis involved hallucinations, which were more prevalent in foster family residents than in nursing home residents (54.7% vs. 37.5%; p = 0.027) (Fig. 1 and Appendix S2).

Discussion

In our study, the clinical profile of older adults and the prevalence of psychiatric symptoms were similar between those residing in foster families and those in nursing homes. The shared prevalence of NPS was 81.1%, comparable to the rates typically observed in nursing homes, which range from 68 to 82%19. The most frequent NPS (over 40%) were delusions, agitation, anxiety, and irritability, with no significant difference in prevalence between the two groups. The NPS have a notable impact on the well-being and quality of life of the residents.20. In a previous study, we observed that subjective quality of life was better in foster families compared to nursing homes21. Given that quality of life is influenced by the environment in long-term care settings22, it is plausible that NPS have a lesser impact on quality of life in foster families compared to nursing homes. The severity of NPS was higher in nursing homes compared to that observed in foster families. Given that the prevalence was the same, foster caregivers may underestimate the severity of NPS. Older adults in foster families often experience little turnover in caregivers over the years. These caregivers may be more accustomed to managing the behavioral disturbances of their residents and may downplay their severity, unlike staff in nursing homes. Indeed, nursing homes are characterized by high staff turnover, work-related stress, and poor working conditions23. However, one cannot exclude that older adults with severe symptoms are more frequently placed in nursing homes rather than in foster families.

The overall prevalence of psychotic disorders, i.e. hallucinations (42.3%), delusions (32.4%), and agitation (46.5%), was higher than that typically reported in the international literature, which generally ranges around 15–20%8,19. This may be attributable to the shortage of psychiatric facilities and psychiatrists in our regions. Such disorders were more severe in nursing homes than in foster families, which could explain the lower use of antipsychotics in foster families. Conversely, anxiolytics were more frequently prescribed in foster families (40.2%), despite the low proportion of patients with severe anxiety disorders. Psychotropic medications were often prescribed. The NPS are managed with psychotropic drugs in nursing homes, with 52–80% of nursing home residents, with or without dementia, receiving at least one prescription24.

A significant difference in terms of frequency and severity concerns apathy, which is much more prominent in nursing homes (20.0% compared to 8.5%). Apathy includes diminished interest, reduced emotional expression or responsiveness, and a lack of initiative, leading to decreased qualitative participation in daily living, social contact, or activities25. In foster families, older adults have close contact with caregivers responsible for their daily activities and are involved in family life, which may provide affective support. A caregiver typically manages an average of two older adults4, in contrast to the common staffing arrangements in nursing homes. In foster families, the older adult is perceived as a member of the family rather than a patient, and participates in daily activities, which could potentially reduce their apathy.

Finally, we observed that appetite and eating disorders were less frequent in foster families compared to nursing homes. The prevalence of malnutrition, assessed using the MNA-SF scale, is similar in foster families (28.0%)26 and in nursing homes (27.6%)27. It is therefore possible that the meals provided in foster families better align with the tastes and preferences of the older adults. Conversely, less flexibility in meal times might explain the lack of appetite observed in nearly a quarter of nursing home residents.

The data from the KASAF and KASEHPAD studies suggest that professional foster families could serve as an alternative to nursing homes, even for older adults with dementia experiencing NPS. The residents in foster families displayed a cognitive, functional, and psychiatric profile very similar to that observed in nursing homes. In nursing homes, the staff often lack specialized training in managing NPS and frequently do not have access to professionals such as psychiatrists and psychologists. The situation is similar in foster families, where caregivers typically receive only brief training lasting a few hours to obtain certification. Nevertheless, psycho behavioral disorders such as agitation, aggression, or depression requiring attention are likely subject to more monitoring in foster families. Indeed, the foster caregiver, who resides with the older adult 24 h a day, can establish familiar routines, interests, or hobbies tailored to the needs and preferences of the elderly person. This also underscores the crucial role of communication, both verbal and non-verbal28, and the interaction between the older adult with dementia and their caregiver29. To enhance the foster family model, we suggest developing both initial and ongoing training for foster caregivers in the management of NPS with which they encounter daily. Another option would be to provide a designated psychologist or psychiatrist for these foster families, who could be consulted in the case of specific disorders.

Our study has several important limitations. The frequency and severity of psychiatric disorders at the time of entry into foster family or nursing homes were not recorded. This information could have helped determine whether the choice for placement in one of the two settings was influenced by the presence of NPS. Moreover, this is a cross-sectional study. Data from the 1-year follow-up will allow us to monitor the progression of NPI score and the associated medications. Indeed, it is not possible to conclude definitively on the lower severity of disorders observed in foster families, particularly psychotic disorders. This observation could be attributed either to a more suitable environment in foster families or to a greater referral of severe cases to nursing homes rather than to foster families. Additionally, NPS were assessed exclusively based on informant reports using the NPI-Q, which may differ from clinical evaluations. Consequently, our findings should be interpreted as informant-reported symptomatology rather than clinical diagnoses. It is also worth noting that the original NPI includes a frequency scale for each symptom alongside the severity scale, whereas the NPI-Q is limited to assessing only the presence of symptoms. Professional care staff may have varied perceptions regarding symptom severity. They may underestimate the severity and distress caused by symptoms, viewing them as intrinsic to dementia and emphasizing their professional expertise in managing residents with diverse neuropsychiatric symptoms. In this regard, the PGI-DSS scale 30 a brief tool that is easy to administer in less than 4 min and structured into four domains (violence, refusal, verbal expressions, and actions), can help prevent inappropriate responses and guide psychosocial interventions. Differential diagnoses (e.g., severe depression, intellectual disability, persistent confusion, etc.) and co-occurring psychiatric diagnoses were not recorded, and nearly one-third of dementia cases lacked an etiological diagnosis. In community-based samples, the prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms has been shown to vary depending on the type of dementia (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body dementia, vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia) 31. Nevertheless, the observed results from the NPI-Q provide a valuable foundation for empirically guiding future interventions on NPS in foster family settings. Finally, follow-up data will assess the association between NPS and health events (such as mortality, hospitalization, and medical consultations), and will also facilitate the analysis of the cost–benefit ratio of each model.

Conclusion

The prevalence of NPS was similar between residents living in foster families and those living in nursing homes. The benefits associated with living in a family setting, such as the bonds between the older adult and the caregiver might explain the lower frequency of certain NPS, such as apathy or lack of appetite. Within the framework of person-centered approaches, foster care could address the unmet personal needs of residents, particularly for older adults or their families who prefer not to enter long-term care facilities, or in countries that do not wish to develop nursing homes.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization (WHO). Ageing and health. Accessed September 2, 2024; https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (2022).

GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 7(2), e105–e125. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00249-8 (2022).

Boucaud-Maitre, D., Cesari, M. & Tabue-Teguo, M. Foster families to support older people with dependency: A neglected strategy. Lancet Healthy Longev. 4(1), e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-7568(22)00288-4 (2023).

Boucaud-Maitre, D. et al. Clinical characteristics of older adults living in foster families in the French West Indies: Baseline screening of the KArukera study of aging in foster families (KASAF) Cohort. Innov. Aging 8(7), 063. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igae063 (2024).

van Duinen-van den IJssel, J. C. L. et al. Nursing staff distress associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms in young-onset dementia and late-onset dementia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 19(7), 627–632 (2018).

García-Martín, V. et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and subsyndromes in patients with different stages of dementia in primary care follow-up (NeDEM project): A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 22(1), 71 (2022).

Peters, M. E. et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms as predictors of progression to severe Alzheimer’s dementia and death: The cache county dementia progression study. Am. J. Psychiatry 172(5), 460–465 (2015).

Choi, A. et al. Impact of psychotic symptoms and concurrent neuropsychiatric symptoms on the quality of life of people with dementia living in nursing homes. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 23(9), 1474-1479.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2022.03.017 (2022).

Okura, T. et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and the risk of institutionalization and death: The aging, demographics, and memory study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 59(3), 473–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03314.x (2011).

Atramont, A. et al. Health status and drug use 1 year before and 1 year after skilled nursing home admission during the first quarter of 2013 in France: A study based on the French National Health Insurance Information System. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 74(1), 109–118 (2018).

Callegari, E., Benth, J. Š, Selbæk, G., Grønnerød, C. & Bergh, S. Does psychotropic drug prescription change in nursing home patients the first 6 months after admission?. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 22(1), 101-108.e1 (2021).

Clement, A., Wiborg, O. & Asuni, A. A. Steps towards developing effective treatments for neuropsychiatric disturbances in Alzheimer’s disease: Insights from preclinical models, clinical data, and future directions. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12, 56 (2020).

Boucaud-Maitre, D. et al. Clinical profiles of older adults in French Caribbean nursing homes: a descriptive cross-sectional study. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 11, 1428443. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1428443 (2024).

Boucaud-Maitre, D. et al. The health care trajectories of older people in foster families: Protocol for an observational study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 12, e40604. https://doi.org/10.2196/40604 (2023).

Cummings, J. L. et al. The neuropsychiatric inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 44(12), 2308–2314. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308] (1994).

Michel, E. et al. Validation of the short version of the neuropsychiatric inventory (NPI-Q). Revue de Gériatrie 30, 385–390 (2005).

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E. & McHugh, P. R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 12, 189–198 (1975).

Katz, S., Ford, A. B., Moskowitz, R. W., Jackson, B. A. & Jaffe, M. W. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of adl: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 185, 914–919 (1963).

Selbæk, G., Engedal, K. & Bergh, S. The prevalence and course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in nursing home patients with dementia: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 14(3), 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2012.09.027 (2013).

Van de Ven-Vakhteeva, J., Bor, H., Wetzels, R. B., Koopmans, R. T. & Zuidema, S. U. The impact of antipsychotics and neuropsychiatric symptoms on the quality of life of people with dementia living in nursing homes. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 28, 530–538 (2013).

Boucaud-Maitre, D. et al. Comparison of quality of life of older adults living in foster families versus nursing homes. Results from the KASA studies. J. Nutr. Health Aging. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnha.2024.100358 (2024).

Jing, W., Willis, R. & Feng, Z. Factors influencing quality of life of elderly people with dementia and care implications: A systematic review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 66, 23–41 (2016).

Peter, K. A. et al. Factors associated with health professionals’ stress reactions, job satisfaction, intention to leave and health-related outcomes in acute care, rehabilitation and psychiatric hospitals, nursing homes and home care organisations. BMC Health Serv. Res. 24(1), 269. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-10718-5 (2024).

Ferreira, A. R., Simões, M. R., Moreira, E., Guedes, J. & Fernandes, L. Modifiable factors associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms in nursing homes: The impact of unmet needs and psychotropic drugs. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 86, 103919 (2020).

Miller, D. S. et al. Diagnostic criteria for apathy in neurocognitive disorders. Alzheimer’s Dementia J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 17(12), 1892–1904 (2021).

Boucaud-Maitre, D. et al. Malnutrition and its determinants among older adults living in foster families in Guadeloupe (French West Indies). A cross-sectional study. PLoS One 19(6), e0304998. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0304998 (2024).

Tabue Teguo, M. et al. Malnutrition and its determinants among older adults living in french caribbean nursing homes: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients 16(14), 2208. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16142208 (2024).

Khan, Z. et al. Investigating the effects of impairment in non-verbal communication on neuropsychiatric symptoms and quality of life of people living with dementia. Alzheimers Dement 7(1), e12172. https://doi.org/10.1002/trc2.12172 (2021).

Strandroos, L. & Antelius, E. Interaction and common ground in dementia: Communication across linguistic and cultural diversity in a residential dementia care setting. Health (London). 21(5), 538–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459316677626 (2017).

Monfort, J. C., Lezy, A. M., Papin, A. & Tezenas du Montcel, S. Psychogeriatric inventory of disconcerting symptoms and syndromes (PGI-DSS): Validity and reliability of a new brief scale compared to the Neuropsychiatric Inventory for Nursing Homes (NPI-NH). Int. Psychogeriatr. 32(9), 1085–1095. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610220000496 (2020).

Bougea, A. et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and α-Synuclein profile of patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. 265(10), 2295–2301 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the ACTIVE Team from Bordeaux for their precious methodological support, as well as Valérie Soter, and Mélanie Petapermal for their regulatory support. We thank the following nursing homes for participating in the study: EHPAD Les Flamboyants (Gourbeyre, Guadeloupe), EHPAD Kalana (Bouillante, Guadeloupe), EHPAD Nou Grand Moun (Capesterre-Belle-Eau, Guadeloupe), EHPAD les Jardins de Belost (Saint-Claude, Guadeloupe), Centre Hospitalier Gerontologique Palais Royal (Les Abymes, Guadeloupe) and Centre Emma Ventura (Fort-de-France, Martinique).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DBM wrote the manuscript. IR, HA, JFD, JMD and MTT reviewed and updated the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boucaud-Maitre, D., Rouch, I., Amieva, H. et al. Comparison of neuro-psychiatric disorders between older adults living in foster families or nursing homes. Sci Rep 15, 7918 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92962-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92962-1