Abstract

This study aims to assess the ion release (Ni, Cr) and surface roughness of metal (M), self-ligating (SL), and ceramic (C) orthodontic brackets after exposure to simulated gastric acid (pH 1.5, pH 3.0) and artificial saliva (pH 7.0). A total of 198 brackets, metal brackets (M) (n = 66) self-ligating (SL) (n = 66), and ceramic brackets (C) (n = 66) were used in this study. Gastric solutions mimicking human gastroesophageal reflux with a pH of 1, 5 or 3 and as a control group pH of 7 (artificial saliva) were used. All specimens were immersed in test solutions for 30 min, 24 h, and 1 month (n = 22 per group). Inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) measured ion release, while an optical profilometer assessed surface roughness. Data were analyzed using One-way ANOVA and t-tests (p < 0.05). Ni and Cr ion release peaked at 24 h and decreased by 1 month (p < 0.05). SL brackets released the most ions, particularly in acidic conditions (p < 0.05). Surface roughness was highest at 24 h, then decreased (p < 0.001), with M brackets showing the greatest roughness and C brackets the lowest (p < 0.001). M and SL brackets had the highest roughness at pH 1.5, while C brackets peaked at pH 3.0 (p < 0.001). Acidic conditions significantly impact ion release and surface roughness. Ceramic brackets may be advantageous for patients with reflux disease, offering reduced corrosion and surface alterations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Orthodontic treatments have become increasingly common across a broader patient demographic, driven by technological advancements and the growing emphasis on aesthetics in modern society. Among adult patients, aesthetic concerns are particularly pronounced, often accompanied by the use of composite and prosthetic restorations. This shift highlights the importance of aesthetic orthodontic options in clinical practice1,2,3.

Orthodontic brackets, a cornerstone of these treatments, are classified based on their material, design, connection type, size, and shape4. These brackets are generally grouped into three categories: metal, ceramic, and plastic5. Ceramic brackets are preferred over plastic ones for their superior durability and aesthetic advantages compared to metal brackets, although allergenic properties remain a critical factor in bracket selection6.

Nowadays, different types of brackets are being manufactured, such as self-ligating brackets, which offer several advantages, such as shorter procedure times, fewer appointments, reduced overall treatment time, and lower friction resistance7. However, like all orthodontic brackets, they are subject to harsh oral conditions, such as humidity, pH, and temperature fluctuations, mechanical forces, and plaque accumulation. These factors contribute to bracket failure through mechanisms such as corrosion and friction8,9,10.

Corrosion is a significant issue in the oral environment, influenced by factors such as chewing forces, occlusion patterns, oral hygiene, dietary habits, and medication use11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. While primarily associated with metals, it also affects ceramics, polymers, and cements, compromising durability and altering material properties. Intraoral corrosion can release harmful ions, posing local and systemic risks16,17,18.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a condition in which stomach acid flows back into the esophagus, exposing orthodontic materials to highly acidic conditions (pH as low as 1.1). This acidity accelerates corrosion, leading to the release of metal ions such as chromium (Cr) and nickel (Ni), which can negatively affect oral tissues and pose systemic risks, including hypersensitivity reactions and potential carcinogenic or mutagenic effects19,20,21.

Previous studies have examined parameters such as enamel surface discoloration and enamel erosion in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease by simulating gastric acid. However, research on the corrosion behavior of different orthodontic brackets under specific acidic conditions remains limited27,28.

This study aims to investigate the impact of gastric acid on the corrosion of metal, ceramic, and self-ligating (SL) brackets by analyzing ions such as nickel and chromium and determining their surface roughness at different time intervals.

The null hypothesis stated that there would be no significant differences in the corrosion and surface characteristics of various orthodontic bracket types when immersed in solutions with varying pH levels.

Material and methods

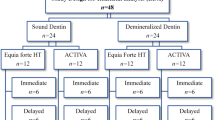

Materials and grouping

This study used three groups: metal brackets (M)(Orthos Metal Twin Brackets, Ormco,California, USA), Self-Ligating brackets (SL)(Damon Ultima, Ormco,California, USA), and ceramic brackets (C) (Aesthetic Twin, Ormco,California, USA) (N = 198, n = 66). The percentages of chromium (chrome), manganese (Mn), iron (Fe), nickel (Ni), Aluminum oxit (Alo), and Oxite composite (Oc) elements are given in Table 1 and Fig. 1 describes the workflow of the present study.

Prepratıon of solutions

The samples in each group were divided into three subgroups, with two different gastric solutions (pH 1.5 and 3) and artificial saliva (pH 7) serving as the control group (n = 22). All solutions were prepared in the Biruni University Faculty of Pharmacy Laboratory.

Artificial saliva was using the following ingredients: 7.69 g/L dipotassium phosphate, 2.46 g/L dipotassium hydrogen phosphate, 5.3 g/L sodium chloride, and 9.3 g/L potassium chloride. The pH was adjusted to 7.0 by adding an appropriate amount of lactic acid.

The gastric solutions mimicking human gastroesophageal reflux were prepared with the following ingredients, 2.0 g of sodium chloride (NaCl), 3.2 g of pepsin, 7.0 mL of hydrochloric acid (HCl), and water. They were adjusted to a pH of 3.0 to represent a moderate gastric insufficiency condition and to a pH of 1.5 to represent a severe gastric insufficiency condition27,28.

All bracket specimens were placed in airtight glass tubes containing 1.5 mL of the respective solution and incubated at 37 °C for three different time intervals: 30 min, 24 h, and 1 month9. The incubations were carried out using an Elektro-mag M5040 P oven (Istanbul, Turkey) with a sample size of n = 22 for each time interval.

Ions release

The release of metal ions from the brackets in the study was quantitatively analyzed using an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) instrument (Thermo Scientific,Germany)21, specifically the Thermo X Series model. This analysis measured the concentrations of nickel (Ni) and chromium (Cr) ions released into the solution over time.(Fig. 2).

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observations were performed at 200× magnification for group M (metal) under the following conditions: pH 1.5 and 3 (gastric acid), and pH 7 (artificial saliva), with evaluation time intervals of 3 min, 24 h, and 1 month. The imaging parameters were standardized across all groups: acceleration voltage (HV) of 15.00 kV, spot size of 3.0, magnification of 1000× , detector type (ETD), mode (SE), working distance (WD) of 8.3–9.8 mm, and scale bar of 200 µm. The analyses were conducted using a Quanta FEG SEM system.

Surface profilometer and SEM (scanning electron microscope)

A surface profilometer equipped with Zeiss Axio CSM700 (Carl Zeiss AG,Göttingen, Germany) Controller software was used to measure the surface roughness of the brackets. The instrument analyzed a total area of 1,087,313.578 µm2. It is capable of non-contact optical measurements and provides high-resolution 3D imaging of surfaces, allowing for detailed analysis of surface roughness, topography, and layer thickness. Additionally, an electron microscope (SEM, Model JEOL JSM-6060, Japan) was used to examine the surface morphology of the specimens. The imaging was conducted at 1000× magnification with an accelerating voltage of 15 keV for M and SL brackets, while 5 keV was used for ceramic brackets to prevent reflections and ensure high-resolution imaging. The measurement results were digitally recorded to form the dataset for this study. (Figs. 2, 3, 4).

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observations were performed at 200 × magnification for group SL (self-ligating) under the following conditions: pH 1.5 and 3 (gastric acid), and pH 7 (artificial saliva), with evaluation time intervals of 3 min, 24 h, and 1 month. The imaging parameters were standardized across all groups: acceleration voltage (HV) of 15.00 kV, spot size of 3.0, magnification of 1000× , detector type (ETD), mode (SE), working distance (WD) of 8.3–9.8 mm, and scale bar of 200 µm. The analyses were conducted using a Quanta FEG SEM system.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observations were performed at 200 × magnification for group C (ceramic) under the following conditions: pH 1.5 and 3 (gastric acid), and pH 7 (artificial saliva), with evaluation time intervals of 3 min, 24 h, and 1 month. The imaging parameters were standardized across all groups: acceleration voltage (HV) of 15.00 kV, spot size of 3.0, magnification of 1000 × , detector type (ETD), mode (SE), working distance (WD) of 8.3–9.8 mm, and scale bar of 200 µm. The analyses were conducted using a Quanta FEG SEM system.

Statistical analyses

The statistical power analysis was conducted using the G*Power software program (v3.0.10). With a significance level (α) set at 0.05, an effect size (f) of 0.4, and a power of 80%, the sample size was determined accordingly to ensure sufficient statistical robustness11.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences). Descriptive statistics were applied, followed by the Kruskal–Wallis test and Mann–Whitney U test to compare the release of nickel (Ni) and chromium (Cr) ions between metal and self-ligating (SL) brackets exposed to gastric fluid for 30 min, 24 h, and 7 days, as the data did not follow a normal distribution.

To determine statistically significant group differences, a Tukey post-hoc test was performed following ANOVA for multiple comparisons of surface roughness (Ra values) across different bracket types and exposure durations. The Tukey test was chosen due to its ability to control the Type I error rate while conducting multiple comparisons.

Results

The evaluated data, presenting the average values of Nickel (Ni) and Chromium (Cr) ion release and surface roughness for M, SL, and C brackets, are summarized in Tables 2, 3, 4 and Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8.

Ni ion release, a significant difference was observed between all brackets at all pH levels after 30 min: M brackets released less Ni at pH 1.5 (t = − 2.842, p < 0.05), more at pH 3.0 (t = 4.689, p < 0.05), and less at pH 7.0 (t = − 8.317, p < 0.05). Cr ion release was consistently higher in SL brackets than in other brackets across all pH levels (pH 1.5: t = − 13.830; pH 3.0: t = − 8.317; pH 7.0: t = − 11.684, all p < 0.05). (Tables 2, 3, Figs. 5, 6).

For 24 h exposure, Ni release was higher in M brackets at pH 1.5 (t = 24.186, p < 0.05) and higher in SL brackets at pH 3.0 and 7.0 (p < 0.05). Over 1 month, M brackets showed higher Ni release at pH 1.5 (t = 5.314, p < 0.05) and 7.0 (t = 18.434, p < 0.05), while no significant difference was observed at pH 3.0 (t = 0.233, p > 0.05). (Tables 2, 3, Figs. 5, 6).

Surface roughness analysis indicated that M brackets had the highest Ra values, while C brackets had the lowest across all pH levels for both 30 min and 1 month exposures (p < 0.017) Similarly, after 1 month of exposure to gastric fluid, M brackets again exhibited the highest surface roughness, with C brackets showing the lowest at pH 1.5 and 3.0 (p < 0.017). At pH 7.0, a significant difference was found between M and SL brackets, and between M and C brackets, with M brackets maintaining the highest surface roughness compared to the other types. (Table 4, Figs. 7, 8).

Discussion

This study demonstrated significant differences in the corrosion behavior and surface properties of orthodontic brackets under varying pH levels and time intervals, leading to the rejection of the null hypothesis. The results highlight that gastric acid environments, as seen in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), exacerbate corrosion and surface changes, particularly in metal and self-ligating brackets9. These findings align with previous studies showing that acidic conditions promote electro-galvanic corrosion, ion release, and biocompatibility concerns3,9,25.

ICP-MS, used in this study, provided precise measurements of ion release, reinforcing its role as a gold-standard technique for detecting trace elements. Consistent with prior research, nickel (Ni) release was significantly higher than chromium (Cr) release, with Ni posing greater biocompatibility risks, including hypersensitivity reactions10.

Consistent with previous studies, this research confirmed that nickel ion release was significantly higher than chromium ion release. House et al16 and Kerosuo et al22 identified nickel as a major concern due to biocompatibility risks like hypersensitivity. Bhaskar et al23 reported elevated nickel release within the first seven days, highlighting the early susceptibility of orthodontic materials to ion leaching. Similarly, Mikulewicz et al12 found Ni release to exceed that of Cr and other ions.

Self-ligating brackets released more nickel ions than conventional brackets from the same manufacturer, highlighting the impact of design and material properties on corrosion and ion release, with potential implications for biocompatibility and patient safety in early orthodontic treatment24.

In this study, self-ligating brackets exhibited the highest nickel ion release during the first 24 h, with metal brackets surpassing them after one month. The consistently higher chromium ion release from self-ligating brackets across all time intervals suggests that material composition and design significantly influence corrosion behavior. Acidic environments (pH 1.5 and 3.0) further intensified nickel and chromium ion release, with the most pronounced effects observed at pH 1.5. These findings reinforce the need for careful consideration of both material properties and bracket design in clinical practice to minimize adverse biological effects and improve long-term stability.

Interestingly, ceramic brackets exhibited superior resistance to corrosion, attributed to the incorporation of Al₂O₃ particles25. Al₂O₃ enhances corrosion resistance by forming a dense, protective oxide layer that increases compactness and reduces porosity in ceramic coatings. This barrier minimizes electrolyte penetration, limiting ion exchange and preventing material degradation. As a result, ceramic brackets remain more stable and less reactive in acidic conditions, consistent with previous findings25,26.

Mann et al27 and Cengiz et al28 investigated the impact of pH levels simulating GERD on corrosion and surface characteristics, confirming the deleterious effects of highly acidic environments. This study effectively simulated real-world conditions by using pH values of 1.5 and 3.0 to represent severe and moderate reflux, providing clinically relevant insights27,28.

The analysis of surface roughness revealed significant pH-dependent variations. Metal and self-ligating brackets displayed the highest surface roughness at pH 1.5, while ceramic brackets maintained the lowest roughness values throughout the study period. Surface roughness peaked within the first 24 h and subsequently decreased over one month. These variations likely reflect differences in material composition and electrochemical interactions with the acidic medium29.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that acidic conditions significantly increase corrosion rates and ion release from orthodontic brackets, with self-ligating and metal brackets being most affected. In contrast, ceramic brackets enhanced with Al₂O₃ particles showed superior corrosion resistance and minimal surface roughness changes. Nickel ion release was highest in self-ligating brackets within the first 24 h, while metal brackets exhibited increased release over time. Surface roughness changes were most pronounced in metal brackets, particularly in acidic environments, underscoring the impact of material composition.

A key limitation of this study was the use of a single corrosion assessment method. While the weight-loss technique provides valuable data, it may not fully capture corrosion dynamics. Future studies should incorporate additional methods, such as electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and SEM, and investigate the effects of temperature and prolonged exposure to enhance clinical relevance and improve the durability of orthodontic materials. These findings emphasize the importance of material selection and design, especially for patients with acidic oral conditions like GERD.

Data availability

The data of this study are available from corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Saccomanno, S. et al. Motivation, perception, and behavior of the adult orthodontic patient: a survey analysis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2754051 (2022).

American Association of Orthodontists®. adult’s guide to orthodontic 2019 https://www3.aaoinfo.org/_/adult-orthodontics/. (2019).

Durgo, K., Orešić, S., Rinčić Mlinarić, M., Fiket, Ž & Jurešić, G. Č. Toxicity of metal ions released from a fixed orthodontic appliance to gastrointestinal tract cell lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(12), 9940 (2023).

Mundhada, V. V., Jadhav, V. V. & Reche, A. A review on orthodontic brackets and their application in clinical orthodontics. Cureus 15(10), e46615 (2023).

Kilponen, L., Varrela, J. & Vallittu, P. K. Priming and bonding metal, ceramic and polycarbonate brackets. Biomater. Investig. Dent. 6(1), 61–72 (2019).

Filho, H. L., Maia, L. H., Araújo, M. V., Eliast, C. N. & Ruellas, A. C. Colour stability of aesthetic brackets: ceramic and plastic. Aust. Orthod. J. 29(1), 13–20 (2013).

Baxi, S. et al. Self-ligating bracket systems: A comprehensive review. Cureus 15(9), e44834 (2023).

Doomen, R. A., Nedeljkovic, I., Kuitert, R. B., Kleverlaan, C. J. & Aydin, B. Corrosion of orthodontic brackets: qualitative and quantitative surface analysis. Angle Orthod. 92(5), 661–668 (2022).

Tahmasbi, S., Sheikh, T. & Hemmati, Y. B. Ion release and galvanic corrosion of different orthodontic brackets and wires in artificial saliva. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 18(3), 222–227 (2017).

Sudha, P. N., Sangeetha, K., Jisha Kumari, A. V., Vanisri, N. & Rani, K. Corrosion of ceramic materials. In Fundamental Biomaterials: Ceramics 1st edn (Elsevier, 2018).

Oana Armencia, A. et al. Analytical study regarding the behavior of Cr-Co and Ni-Cr in saliva. Medicina 58(11), 1524 (2022).

Mikulewicz, M. et al. Mapping chemical elements on the surface of orthodontic appliance by SEM-EDX. Med. Sci. Monit. 20, 860–865 (2014).

Mirhashemi, S. A., Jahangiri, S., Moghaddam, M. M. & Bahrami, R. Assessment of the rate of orthodontic appliances ion release in different mouthwashes: An overview. J. Dent. Med. 4(32), 255–264 (2020).

Chantarawaratit, P. O. & Yanisarapan, T. Exposure to the oral environment enhances the corrosion of metal orthodontic appliances caused by fluoride-containing products: Cytotoxicity, metal ion release, and surface roughness. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 160(1), 101–112 (2021).

Okokpujie, I. P., Tartibu, H. H. & Adeoye, A. O. M. Effect of coatings on mechanical, corrosion, and tribological properties of industrial materials: A comprehensive review. J. Bio. Tribo. Corros. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40735-023-00805-0 (2023).

House, K., Sernetz, F., Dymock, D., Sandy, J. R. & Ireland, A. J. Corrosion of orthodontic appliances – should we care?. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 133, 584–592 (2008).

Lkhagvaa, T., Rehman, Z. U. & Choi, D. Post-anodization methods for improved anticorrosion properties: A review. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 18, 1–17 (2021).

Martinez-Huitle, C. A., Rodrigo, M. A., Sirés, I. & Scialdone, O. A critical review on latest innovations and future challenges of electrochemical technology for the abatement of organics in water. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 328, 122430 (2023).

Katz, P. O. et al. ACG clinical guideline for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 117(1), 27–56 (2022).

Kovač, V., Poljšak, B., Primožič, J. & Jamnik, P. Are metal ions that make up orthodontic alloys cytotoxic, and do they induce oxidative stress in a yeast cell model?. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(21), 7993 (2020).

Chojnacka, K. et al. Using XRF and ICP-OES in biosorption studies. Molecules 23(8), 2076 (2018).

Kerosuo, H., Moe, G. & Hensten-Pettersen, A. Salivary nickel and chromium in subjects with different types of fixed orthodontic appliances. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 111, 595–598 (1997).

Bhaskar, V. & Subba Reddy, V. V. Biodegradation of nickel and chromium from space maintainers: an in vitro study. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 28(1), 6–12 (2010).

Maia, L. H., Lopes Filho, H., Ruellas, A. C., Araújo, M. T. & Vaitsman, D. S. Corrosion behavior of self-ligating and conventional metal brackets. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 19(2), 108–114 (2014).

Wei, J. et al. Effect of Al₂O₃ on microstructure and corrosion characteristics of Al/Al₂O₃ composite coatings prepared by cold spraying. Metals 14, 179 (2024).

Liu, X., Lin, J. & Ding, P. Changes in the surface roughness and friction coefficient of orthodontic bracket slots before and after treatment. Scanning 35(4), 265–272 (2013).

Cengiz, S., Sarac, S. & Ozcan, M. Effects of simulated gastric juice on color stability, surface roughness, and microhardness of laboratory-processed composites. Dent. Mater. J. 33(3), 343–348 (2014).

Mann, C. et al. Three-dimensional profilometric assessment of early enamel erosion simulating gastric regurgitation. J. Dent. 42(11), 1411–1421 (2014).

Erdogan, A. T., Nalbantgil, D., Ulkur, F. & Sahin, F. Metal ion release from silver soldering and laser welding caused by different types of mouthwash. Angle Orthod. 85(4), 665–667 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank İsmail Tuncer Değim for preparing solutions with Biruni University Faculty of Pharmacy Laboratory support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.G.U and M.G. study design. D.G.U. Experiments and data analyses. R.S prepared figures and Tables. D.G.U and R.S. wrote the main manuscricp. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Umurca, D.G., Sasany, R. & Gülyurt, M. Analysis of corrosion, surface roughness, and ıon release of orthodontic brackets in simulated gastric acid and saliva. Sci Rep 15, 14984 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93039-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93039-9